Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

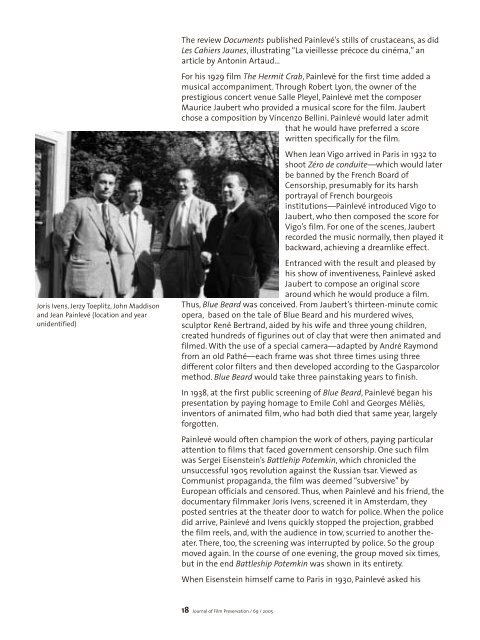

Joris Ivens, Jerzy Toeplitz, John Maddison<br />

and Jean Painlevé (location and year<br />

unidentified)<br />

The review Documents published Painlevé’s stills <strong>of</strong> crustaceans, as did<br />

Les Cahiers Jaunes, illustrating “La vieillesse précoce du cinéma,” an<br />

article by Antonin Artaud...<br />

For his 1929 film The Hermit Crab, Painlevé for the first time added a<br />

musical accompaniment. Through Robert Lyon, the owner <strong>of</strong> the<br />

prestigious concert venue Salle Pleyel, Painlevé met the composer<br />

Maurice Jaubert who provided a musical score for the film. Jaubert<br />

chose a composition by Vincenzo Bellini. Painlevé would later admit<br />

that he would have preferred a score<br />

written specifically for the film.<br />

When Jean Vigo arrived in Paris in 1932 to<br />

shoot Zéro de conduite—which would later<br />

be banned by the French Board <strong>of</strong><br />

Censorship, presumably for its harsh<br />

portrayal <strong>of</strong> French bourgeois<br />

institutions—Painlevé introduced Vigo to<br />

Jaubert, who then composed the score for<br />

Vigo’s film. For one <strong>of</strong> the scenes, Jaubert<br />

recorded the music normally, then played it<br />

backward, achieving a dreamlike effect.<br />

Entranced with the result and pleased by<br />

his show <strong>of</strong> inventiveness, Painlevé asked<br />

Jaubert to compose an original score<br />

around which he would produce a film.<br />

Thus, Blue Beard was conceived. From Jaubert’s thirteen-minute comic<br />

opera, based on the tale <strong>of</strong> Blue Beard and his murdered wives,<br />

sculptor René Bertrand, aided by his wife and three young children,<br />

created hundreds <strong>of</strong> figurines out <strong>of</strong> clay that were then animated and<br />

filmed. With the use <strong>of</strong> a special camera—adapted by André Raymond<br />

from an old Pathé—each frame was shot three times using three<br />

different color filters and then developed according to the Gasparcolor<br />

method. Blue Beard would take three painstaking years to finish.<br />

In 1938, at the first public screening <strong>of</strong> Blue Beard, Painlevé began his<br />

presentation by paying homage to Emile Cohl and Georges Méliès,<br />

inventors <strong>of</strong> animated film, who had both died that same year, largely<br />

forgotten.<br />

Painlevé would <strong>of</strong>ten champion the work <strong>of</strong> others, paying particular<br />

attention to films that faced government censorship. One such film<br />

was Sergei Eisenstein’s Battlehip Potemkin, which chronicled the<br />

unsuccessful 1905 revolution against the Russian tsar. Viewed as<br />

Communist propaganda, the film was deemed “subversive” by<br />

European <strong>of</strong>ficials and censored. Thus, when Painlevé and his friend, the<br />

documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens, screened it in Amsterdam, they<br />

posted sentries at the theater door to watch for police. When the police<br />

did arrive, Painlevé and Ivens quickly stopped the projection, grabbed<br />

the film reels, and, with the audience in tow, scurried to another theater.<br />

There, too, the screening was interrupted by police. So the group<br />

moved again. In the course <strong>of</strong> one evening, the group moved six times,<br />

but in the end Battleship Potemkin was shown in its entirety.<br />

When Eisenstein himself came to Paris in 1930, Painlevé asked his<br />

18 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 69 / 2005