FOcus On - International Press Institute

FOcus On - International Press Institute

FOcus On - International Press Institute

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

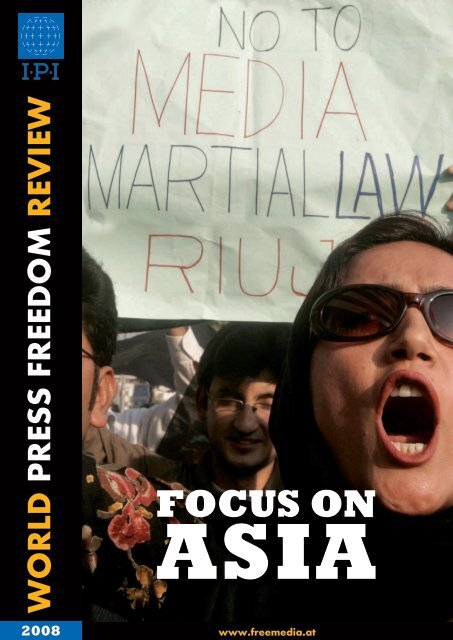

World <strong>Press</strong> Freedom revieW<br />

2008<br />

<strong>FOcus</strong> <strong>On</strong><br />

AsiA<br />

www.freemedia.at

The IPI World <strong>Press</strong> Freedom Review is dedicated<br />

to the 66 journalists who lost their lives in 2008<br />

Gadzhi Abashilov<br />

Sarwa Abdul-Wahab<br />

Benefredo Acabal<br />

Dyar Abas Ahmed<br />

Jassim al-Batat<br />

Alaa Abdul-Karim Al-Fartoosi<br />

Qassim Abed El-Hussein Al-Iqbai<br />

Abdulla Telman Alishayev<br />

Haidar al-Husseini<br />

Mohieldin Al-Naqib<br />

Shihab Al-Tamimi<br />

Eiphraim Audu<br />

Chalee Boonsawat<br />

José Armando Rodríguez Carreón<br />

Athiwat Chaiyanurat<br />

Grigol Chikhladze<br />

Dennis Cuesta<br />

Paranirupasingham Devakumar<br />

Nasteh Dahir Farah<br />

Niko Franjic<br />

Pierre Fould Gerges<br />

Soran Mama Hama<br />

Hisham Mijawet Hamdan<br />

Hassan Kafi Hared<br />

Abdul Razzak Johra<br />

Jagat Prasad Joshi<br />

Trent Keegan<br />

Mohammed Ibrahim Khan<br />

Alexander Klimchuk<br />

Walter Lessa de Oliveira<br />

Musab Mahmood<br />

Teresa Bautista Merino<br />

Leo Mila<br />

Javed Ahmed Mir<br />

Rashmi Mohamed<br />

Ihab Mu’d<br />

Abdus Samad Chishti Mujahid<br />

Mohammed Muslimuddin<br />

Didace Namujimbo<br />

Wissam Ali Ouda<br />

Aristeo Padrigao<br />

Jorge Mérida Pérez<br />

Ivo Pukanic<br />

Carlos Quispe Quispe<br />

Giorgi Ramishvili<br />

Jaruek Rangcharoen<br />

Vikas Ranjan<br />

Normando García Reyes<br />

Abdul Samad Rohani<br />

Martin Roxas<br />

Jagjit Saikia<br />

Ahmed Salim<br />

Khim Sambo<br />

Felicitas Martínez Sánchez<br />

Abdul Aziz Shaheen<br />

Khadim Hussain Shaikh<br />

Fadel Shana<br />

Pushkar Bahadur Shrestha<br />

Ilyas Shurpayev<br />

Ashok Sodhi<br />

Stan Storimans<br />

Carsten Thomassen<br />

Siraj Uddin<br />

Miguel Angel Villagómez Valle<br />

Magomed Yevloyev<br />

Alejandro Zenon Fonseca Estrada

IPI Headquarters<br />

Spiegelgasse 2/29<br />

A-1010 Vienna, Austria<br />

Telephone +43 (1) 512 90 11<br />

Fax +43 (1) 512 90 14<br />

ipi@freemedia.at<br />

http://www.freemedia.at<br />

Registered in Zurich<br />

Janne Virkkunen David Dadge Uta Melzer<br />

IPI Chairman IPI Director Managing Editor<br />

and Publisher<br />

Editors Asia Africa The Americas<br />

Michael Kudlak Andrew Horvat Uta Melzer Michael Kudlak<br />

Colin Peters Naomi Hunt<br />

Timothy Spence Nayana Jayarajan<br />

Patti McCracken<br />

Uta Melzer<br />

Colin Peters<br />

Barbara Trionfi<br />

Australasia Middle East<br />

and Oceania The Caribbean Europe and North Africa<br />

Colin Peters Charles Arthur Colin Peters Naomi Hunt<br />

Logo and<br />

Researcher Layout Cover Design<br />

Franz Brugger Günther Bauer Elisabeth Birkhan

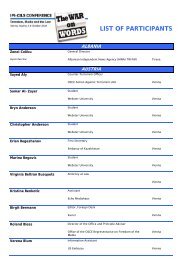

Content<br />

Global Overview..................................4<br />

Asia Overview ....................................6<br />

Death by Numbers ..............................8<br />

Afghanistan........................................10<br />

Bangladesh ........................................12<br />

Mission:<br />

<strong>Press</strong> Freedom in Bangladesh ......................13<br />

Justice Denied:<br />

The case of Mohammad<br />

Atiqullah Khan Masud ......................15<br />

Bhutan ................................................16<br />

Burma (Myanmar)..............................17<br />

Cambodia ..........................................20<br />

People’s Republic of China ..............22<br />

Hong Kong ........................................24<br />

India....................................................25<br />

Notes From the Field: India ............28<br />

Indonesia............................................30<br />

Notes From the Field: Indonesia ....32<br />

Balibo Revisited ................................33<br />

Japan ..................................................34<br />

Kazhakstan ........................................36<br />

Krgyzstan ..........................................37<br />

Laos ....................................................39<br />

Malaysia ............................................41<br />

Notes from the Field: Malaysia........43<br />

Maldives ............................................44<br />

Mongolia ............................................45<br />

Nepal ..................................................47<br />

Mission: <strong>Press</strong> Freedom in Nepal..............49<br />

Dialogue for a Free Media ................51<br />

North Korea........................................52<br />

Pakistan..............................................53<br />

Philippines..........................................55<br />

Singapore ..........................................57<br />

South Korea........................................59<br />

Sri Lanka ............................................60<br />

Mission:<br />

<strong>Press</strong> Freedom in Sri Lanka........................63<br />

Justice Denied:<br />

The case of Subramaniyam<br />

Sukirtharajan......................................64<br />

Taiwan................................................65<br />

Tajikistan............................................66<br />

Thailand ............................................68<br />

Notes From the Field: Thailand ......70<br />

Turkmenistan ....................................70<br />

Uzbekistan..........................................72<br />

Vietnam ..............................................74<br />

Africa Overview ................................76<br />

Americas Overview ..........................80<br />

Europe Overview ..............................83<br />

Middle East and<br />

North Africa Overview......................86<br />

Australasia and<br />

Oceania Overview ............................89<br />

Caribbean Overview ........................91<br />

IPI Death Watch ................................94<br />

Acknowledgments ..........................100

4<br />

Egyptian journalists protest in Cairo with posters showing Ibrahim Eissa, editor of the independent Al-Dustor newspaper,<br />

after an appeals court upheld a guilty verdict against him for stories questioning the Egyptian president's health. (AP, Amr Nabil)

By Uta Melzer Managing Editor<br />

How Numbers Can Lie<br />

Ninety-three killed in 2007, 66 in 2008. If numbers could tell full stories,<br />

the plunge in recor ded journalist deaths might have encouraged sighs of relief.<br />

But as this year’s IPI World <strong>Press</strong> Freedom Review underscores,<br />

these statistics mean little in light of the myriad forms of censorship available<br />

to those looking to suppress news and information.<br />

This year IPI focuses on Asia,<br />

which proved the region deadliest<br />

for journalists in 2008, lar -<br />

gely due to a string of killings in India,<br />

Pakistan and the Philippines. But journalists<br />

in other corners of the glo be died<br />

in disturbing numbers, such as in Iraq,<br />

Mexico, Georgia and Russia, where the<br />

apparent execution-style kil ling of an In -<br />

gushetian reporter unnerved a journalistic<br />

community long accustom ed to harrowing<br />

violence.<br />

Other developments showed that jour -<br />

nalists, a competitive bunch, have good<br />

reason for increased solidarity in light of<br />

the strikingly similar challenges they face<br />

worldwide.<br />

Judicial harassment dressed up as<br />

national security protection, in the past<br />

much criticized in the United States,<br />

also permitted authorities to intimidate<br />

outspo ken journalists in places such as<br />

Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Malaysia, China<br />

and Iran.<br />

The European Union’s anti-terrorism<br />

efforts subtly encroached on the media,<br />

with the implementation of a directive<br />

requiring the retention of communications<br />

data for potential use in criminal<br />

investigations, a headache for those looking<br />

to protect their sources.<br />

Censorship in the name of tradition,<br />

religion, culture and national reputation<br />

was also widespread. In Thailand, laws<br />

protecting the reputation of the mon -<br />

arch prompted judicial proceedings and<br />

led to the shutdown of more than<br />

2.000 websites. In parts of the Middle<br />

East and North Africa, laws forbidding<br />

insults to Islam continued to carry the<br />

death penalty.<br />

Turkey’s government resisted deeper<br />

reform to its prohibitions on “insults to<br />

Turkishness”, half-heartedly rewording<br />

the law to forbid insults to the “Turkish<br />

nation”. In Slovenia, a country that held<br />

the EU presidency in the first half of<br />

2008, parties angered by media coverage<br />

repeatedly pushed for the prosecution of<br />

journalists under laws forbidding insults<br />

to the state.<br />

Global calls to rid legal systems of cri -<br />

minal penalties for defamation, whether<br />

involving the reputation of states, political<br />

leaders or individuals, met with little<br />

success. With many Western European<br />

nations failing to take the lead in such<br />

reform, it is not surprising that authoritarian<br />

leaders elsewhere readily relied on<br />

such provisions to harass journalists, particularly<br />

in African countries such as The<br />

Gambia and Zimbabwe, and Asian countries<br />

such as Indonesia and Singapore.<br />

Developments showed<br />

that journalists have<br />

good reason for increased<br />

solidarity in light of the<br />

strikingly similar challenges<br />

they face worldwide<br />

Source protection was a major issue<br />

not just in Europe. In the United States,<br />

courts squared off against journalists with<br />

respect to the issue, and moves for a federal<br />

media shield law saw some progress.<br />

In Australia, reticent journalists were<br />

threa tened with contempt proceedings,<br />

and had their premises and homes raided.<br />

But the news was not all grim. Chile<br />

and Guatemala approved access-to-information<br />

laws. Nepal created a National<br />

In formation Commission to implement<br />

the previously enacted Right to Informa -<br />

tion Act. Bangladesh too saw a new law<br />

on the right to information, though various<br />

insufficiencies resulted in relatively<br />

muted celebrations. The Cook Islands<br />

took the lead in Oceania, becoming the<br />

first nation to introduce a right to information<br />

law in that region. Disappoint -<br />

ing ly, Nigeria’s government once again<br />

stalled consideration of the ever-pending<br />

Freedom of Information Bill.<br />

<strong>Press</strong> freedom organizations often re -<br />

mind politicians that they do not have to<br />

love the media, but should respect journalists’<br />

duty to be watchdogs and to in -<br />

form the public. Public leaders showed<br />

little resistance to the first part of that<br />

adage, with leaders in Sri Lanka, Turkey,<br />

Venezuela, Ecuador and Slovenia engaging<br />

in particularly hostile anti-media<br />

rhetoric. Fiji’s interim prime minister took<br />

things a step further, and, irked by their<br />

coverage, simply had two non-citizen<br />

journalists placed on a plane out of the<br />

country before immigration officials could<br />

review the legality of such a measure.<br />

Containing cyberspace was another<br />

ambitious effort into which authorities<br />

worldwide put much energy. In the Mid -<br />

dle East and Central Asia, this largely<br />

came in the form of new user registration<br />

requirements. Even the democratic government<br />

of South Korea said it is considering<br />

such measures. In China, cartoon<br />

police officers that popped up on computer<br />

screens when Internet users there<br />

accessed illegal content were no laughing<br />

matter for those all too familiar with the<br />

real thing.<br />

Silence was another chilling trend. In<br />

Eritrea, little information trickled out of<br />

the country about the dozen or more<br />

journalists languishing in jail since as<br />

early as 2001. In Mexico, eight journalists<br />

have simply gone missing as of 2008.<br />

5

6<br />

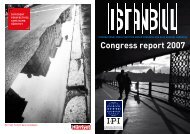

Asia By Barbara Trionfi<br />

Cyber-Censorship Finds a Home<br />

In a region replete with repressive governments, intolerance of dissent is only<br />

one of many obstacles to media freedom. Investigative journalists face wanton<br />

attacks, while reporters routinely find themselves in the cross-fire of ethnic,<br />

religious and political turf wars. Government failure, aloofness or unwillingness<br />

to bring the perpetrators to justice serves as encouragement for further attacks.<br />

Pakistani journalists and members of civil society chant slogans during a rally to mark World<br />

<strong>Press</strong> Freedom Day, on 3 May 2008 in Islamabad, Pakistan. (AP Photo/Anjum Naveed)<br />

The Internet continues to be a battleground<br />

between journalists<br />

and their censors, while two<br />

Asian countries – China and Vietnam –<br />

maintain a leading role as jailers of cyber<br />

dissidents.<br />

Propelled by Internet and mobile messaging,<br />

news spread fast of major events,<br />

including the protests in Tibet, the escalation<br />

of violence in Sri Lanka, massive<br />

anti-government demonstrations in Thailand,<br />

and calamities such as the Sichuan<br />

earthquake in China and cyclone Nargis<br />

in Burma. Much of the more sensitive<br />

information related to these events would<br />

never have reached the public had it not<br />

been for the courageous efforts of repor -<br />

ters to uncover what governments tried<br />

to cloak.<br />

Despite China’s efforts to liberalise its<br />

economy, its centralised rule and intolerance<br />

of dissent create inherent tensions for<br />

both foreign and Chinese journalists.<br />

Attacks against journalists perceived as<br />

damaging China’s image have been nu m -<br />

erous. Foreign journalists received death<br />

threats after state-run media ran reports<br />

critical of the international coverage of the<br />

Tibet unrest, and Chinese journalists were<br />

locked up for reports deemed negative.<br />

Despite China’s efforts<br />

to liberalise its economy,<br />

its centralised rule and<br />

intolerance of dissent<br />

create inherent tensions<br />

for both foreign and<br />

Chinese journalists<br />

In semiautonomous Hong Kong, one<br />

magazine board decided to drop an article<br />

suggesting that Hong Kong-style<br />

autonomy might be the best solution<br />

for Tibet. The decision raised concerns<br />

about the increasing influence of pro-<br />

Beijing forces in the Hong Kong Special<br />

Administrative Region and its consequence<br />

on its citizens’ rights.<br />

Jing and Cha are the two cartoon figures of<br />

"virtual cops" that patrol the Internet in China<br />

(AP Photo/Beijing Public Security Bureau, HO)<br />

Meanwhile, criminal defamation and<br />

lack of judicial independence represent a<br />

serious threat to press freedom in many<br />

Asian countries.<br />

In the Philippines, a Daily Tribune<br />

reporter was sentenced to a prison term<br />

of up to two years and 10 months for an<br />

article she wrote alleging corruption in a<br />

contract-bidding deal.<br />

Courts in Indonesia have struck<br />

down laws that criminalised defamation<br />

of the government and insults to the pre -<br />

sident and vice president, calling them<br />

unconstitutional. However, defamation<br />

in general remains a criminal offence.<br />

Violations of the newly passed Electronic<br />

Information and Transaction Law, forbidding<br />

the distribution of insulting or<br />

defamatory information in electronic<br />

form, are punishable with a maximum of<br />

six years in prison and high fines.<br />

Thailand has witnessed a number of<br />

complaints and prosecutions in connection<br />

with draconian laws that forbid criticism<br />

of the monarch. The laws foster le -

gal harassment of journalists and self-censorship.<br />

Furthermore, the government has<br />

reported that it has blocked 2,300 websites<br />

including messages deemed insulting<br />

to monarchy. This year, BBC correspondent<br />

Jonathan Head was harassed<br />

by a police officer who alleged that the<br />

reporter had offended the king. Under<br />

Thai law, lèse-majesté charges can be<br />

brought by any citizen.<br />

In a separate case, Australian author<br />

Harry Nicolaides was jailed on 31 August<br />

for three sentences he wrote about the<br />

royal family in his 2005 novel, “Veri si -<br />

militude”.<br />

The Vietnamese government’s<br />

crackdown on free<br />

speech resulted in the arrest<br />

of at least 10 journalists<br />

Criminal defamation is not the only<br />

law used to jail journalists in Asia. In<br />

Burma, popular comedian Zarganar was<br />

sentenced to 45 years for violating the<br />

Electronics Act by videotaping cyclone<br />

damage and criticizing the ruling military<br />

junta’s lacklustre relief efforts. Three<br />

other journalists were sentenced to bet -<br />

ween 15 and 29 years under the Elec -<br />

tronics Act for their involvement in helping<br />

cyclone survivors. A blogger, Nay<br />

Phone Latt, was sentenced to 20 years in<br />

prison for posting a poem criticizing the<br />

country’s ruling general.<br />

The Vietnamese government’s crackdown<br />

on free speech resulted in the ar -<br />

rest of at least 10 journalists, five of<br />

whom are now serving prison terms on<br />

charges of abuse of power, tax evasion<br />

and terrorism.<br />

Licensing requirements for newspapers,<br />

a practice IPI has repeatedly condemned,<br />

have been used by the authorities<br />

in Malaysia to censor critical voices.<br />

In April, the Tamil-language newspaper<br />

Makkal Osai, known for its criticism of<br />

one of the ruling parties, received a letter<br />

from the Ministry of Home Affairs stating<br />

that its application for a new permit<br />

had been denied.<br />

Governments of the Central Asian<br />

re publics also strictly control the allocation<br />

of broadcasting and, in some<br />

cases, newspaper licenses. State control<br />

over printing and distribution facilities<br />

represents a fur ther obstacle press freedom<br />

in this re gion, where physical at -<br />

A Tibetan motorcyclist rides past closed shops with a banner demanding media freedom<br />

in Tibet, in Dharmsala, India, Sunday, March 23, 2008. (AP Photo/Ashwini Bhatia)<br />

tacks and imprisonment of journalists<br />

are not uncommon.<br />

Conflicts along political, ethnic and<br />

religious lines in South Asia have become<br />

the greatest threats to journalists in the<br />

region. Of the 26 journalists who lost<br />

their lives in the line of duty in Asia in<br />

2008, 17 were killed in Afghanistan,<br />

Pakistan, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka.<br />

Of the 26 journalists who<br />

lost their lives in the line<br />

of duty in Asia in 2008,<br />

17 were killed in Afghan -<br />

istan, Pakistan, India,<br />

Nepal and Sri Lanka<br />

Investigative journalists are also in the<br />

line of fire. Four of the journalists killed<br />

in the Philippines in 2008, as well as two<br />

of the three journalists killed in Thai -<br />

land, one in Cambodian and three in<br />

South Asia, were known for their reports<br />

on corruption.<br />

Asian authorities have often expressed<br />

the need to control the Internet – a growing<br />

source of independent information.<br />

In an amusing stab at unfettered media<br />

access, Chinese authorities use “Jing” and<br />

“Cha” – two cartoon police officers that<br />

regularly pop up on Internet users’<br />

screens warning them of illegal content.<br />

Illegal content includes anything deemed<br />

as subversive or promoting superstition.<br />

Efforts to censor website content and<br />

force registration of Internet users have be -<br />

come more routine in China, Singa pore,<br />

Vietnam, Malaysia, Burma and the Cen -<br />

tral Asian republics. However, this year’s<br />

announcement by the government in<br />

South Korea that it would consider new<br />

laws to control the spread of false information<br />

on the Internet came as discouraging<br />

news for a nation that has become one<br />

of the region’s steadiest de mocracies.<br />

Under the Korean proposal, all users of<br />

cyber-forums and chat rooms would be<br />

required to register using their real names.<br />

7

E R<br />

RIA<br />

ja<br />

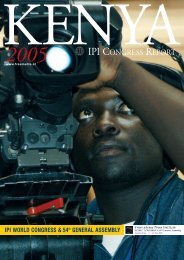

Death by Numbers Asia Deadliest Region for Journalists in 2008<br />

BELARUS<br />

CZECH REP. U K R A I N E<br />

SLOVAKIA<br />

LIECH.<br />

MOLDOVA<br />

AUSTRIA<br />

Lake Balkhash<br />

HUNGARY<br />

ROMANIA<br />

Sea of<br />

Azov<br />

Aral<br />

SAN<br />

Sea<br />

MARINO<br />

SERBIA<br />

ITALY<br />

Black Sea<br />

GEORGIA<br />

Caspian<br />

MONT. Sea<br />

ALB.<br />

ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN<br />

Indian<br />

1972<br />

claim<br />

Line of Control<br />

UNISIA<br />

SYRIA<br />

CYPRUS<br />

Line of<br />

Mediterranean Sea<br />

IRAQ<br />

Actual<br />

LEBANON<br />

AFGHANISTAN<br />

Control<br />

I R A N<br />

Persian<br />

Gulf<br />

Gulf of Oman<br />

Red<br />

Sea<br />

PAKISTAN<br />

BAN<br />

KOS.<br />

Hamburg<br />

Samara<br />

Barnaul<br />

Berlin Warsaw<br />

Lódz Homyel<br />

Voronezh Saratov<br />

Orenburg<br />

ne<br />

Astana<br />

POLAND<br />

RMANY Prague<br />

Kyiv<br />

Kraków<br />

Qaraghandy<br />

L'viv<br />

rankfurt<br />

(Karaganda)<br />

ourg<br />

Kharkiv Volgograd<br />

unich Vienna Bratislava<br />

Donets'k<br />

K A Z A K H S T A N<br />

Budapest Chisinau<br />

Rostov<br />

Atyraü<br />

n<br />

SLOVENIA<br />

Odesa<br />

Astrakhan'<br />

Ljubljana<br />

Milan<br />

CROATIA<br />

n Zagreb Belgrade<br />

BOS. & Bucharest<br />

oa<br />

HER.<br />

Aqtaü<br />

Ürümqi<br />

Sarajevo<br />

(Aktau)<br />

Almaty<br />

Pristina Sofia<br />

VATICAN Podgorica<br />

BULGARIA<br />

Shymkent<br />

CITY<br />

Tbilisi<br />

Bishkek<br />

Rome Tirana<br />

Skopje<br />

Istanbul<br />

Tashkent KYRGYZSTAN<br />

MACEDONIA<br />

Naples<br />

Ankara<br />

UZBEKISTAN<br />

Bursa<br />

Yerevan<br />

Baku<br />

Kashi<br />

(IT.)<br />

GREECE . T U R K E Y<br />

TURKMENISTAN<br />

Palermo<br />

Izmir<br />

Dushanbe<br />

Konya<br />

Ashgabat<br />

Athens<br />

TAJIKISTAN<br />

Adana Gaziantep<br />

Tabriz ¯<br />

(IT.)<br />

Mosul<br />

Mashhad<br />

unis MALTA Valletta<br />

Aleppo<br />

Tehran<br />

Nicosia<br />

Arbil<br />

Qom<br />

Herāt Kabul<br />

(GR.)<br />

Beirut<br />

Peshāwar<br />

Damascus<br />

Kermanshah<br />

Tripoli<br />

Es¸fahān<br />

Tel Aviv-Yafo<br />

Baghdad<br />

Islamabad<br />

Banghāzī<br />

ISRAEL<br />

Kandahār<br />

Alexandria<br />

Jerusalem Amman<br />

Ahvāz<br />

Lahore<br />

Faisalābād<br />

Cairo JORDAN<br />

Al Bas¸rah<br />

Quetta Multān Ludhiāna<br />

L I B Y A<br />

Al Jizah ¯<br />

E G Y P T<br />

Aswān<br />

KUWAIT<br />

Kuwait<br />

Shirāz ¯ Zāhedān<br />

SAUDI BAHRAIN<br />

OMAN<br />

Manama Abu<br />

Medina Riyadh Doha Dhabi<br />

QATAR UNITED ARAB Muscat<br />

EMIRATES<br />

ARABIA<br />

Jiddah<br />

Mecca<br />

OMAN<br />

Hyderābād<br />

Karāchi<br />

New<br />

Delhi<br />

NEPAL<br />

Āgra Kathmandu<br />

Jaipur<br />

Kānpur<br />

Lucknow<br />

Patna<br />

Ahmadābād Bhopāl<br />

Jamshedpur<br />

Indore<br />

Ko<br />

Sūrat<br />

Nāgpur<br />

.<br />

Sardinia<br />

Sicily<br />

Crete<br />

no<br />

CAMEROON<br />

Douala<br />

CHAD<br />

N'Djamena<br />

CENTRAL<br />

AFRICAN REPUBLIC<br />

Bangui<br />

Afghanistan (2)<br />

Abdul Samad Rohani,<br />

8 June<br />

Carsten Thomassen,<br />

14 January<br />

Omdurman<br />

Khartoum<br />

S U D A N<br />

Nyala<br />

Lake<br />

Nyasa<br />

ERITREA<br />

Asmara<br />

Pakistan (6)<br />

Addis<br />

Ababa<br />

ETHIOPIA<br />

M i<br />

Abdul Razzak Johra,<br />

3 November<br />

Abdul Aziz Shaheen,<br />

29 August<br />

Mohammed Ibrahim Khan,<br />

22 May<br />

Khadim Hussain Shaikh,<br />

14 April<br />

Siraj Uddin, 29 February<br />

Abdus Samad Chishti<br />

Mujahid, 9 February<br />

YEMEN<br />

Sanaa<br />

Aden<br />

Gulf of Aden<br />

DJIBOUTI<br />

Djibouti<br />

SOMALIA<br />

Glorioso Islands<br />

(F CE)<br />

Socotra<br />

(YEMEN)<br />

REP. OF<br />

UGANDA<br />

KENYA<br />

GABON THE<br />

CONGO RWANDA<br />

Lake<br />

Victoria<br />

BURUNDI<br />

ANGOLA<br />

Cabinda)<br />

Lake<br />

Tanganyika TANZANIA<br />

SEYCHELLES<br />

DEMOCRATIC<br />

Yaounde<br />

Libreville<br />

Kisangani Kampala<br />

Mogadishu<br />

Nairobi<br />

Kigali<br />

REPUBLIC<br />

Bujumbura<br />

Brazzaville<br />

-Noire OF THE CONGO<br />

Mombasa<br />

Kinshasa<br />

Mbuji-Mayi<br />

Dodoma<br />

Dar es Salaam<br />

Luanda<br />

Victoria<br />

8<br />

Lubumbashi<br />

Juba<br />

Port Sudan<br />

Kassala<br />

Hargeysa<br />

Nepal (2)<br />

Arabian<br />

Sea<br />

Jagat Prasad Joshi,<br />

28 November<br />

Pushkar Bahadur Shrestha,<br />

12 January<br />

Mumbai<br />

LAKSHADWEEP<br />

(INDIA)<br />

MALDIVES<br />

British Indian<br />

Ocean Territory<br />

(U.K.)<br />

Pune<br />

Calicut<br />

Laccadive<br />

Sea<br />

Sri Lanka (2)<br />

I N D I A<br />

Hyderābād<br />

Bengaluru<br />

Cochin<br />

Male<br />

Diego<br />

Garcia<br />

Vijayawāda<br />

Rashmi Mohamed,<br />

6 October<br />

Paranirupasingham<br />

Devakumar, 28 May<br />

Coimbatore<br />

Madurai<br />

Chennai<br />

Vishākh<br />

Colombo<br />

SRI<br />

LANKA

Lhasa<br />

BHUTAN<br />

Thimpu<br />

GLADESH<br />

Dhaka<br />

Khulna<br />

kata Chittagong<br />

apatnam<br />

Irkutsk<br />

Bay of<br />

Bengal<br />

M O N G O L I A<br />

NICOBAR<br />

ISLANDS<br />

(INDIA)<br />

C H I N A<br />

BURMA<br />

Rangoon<br />

Mandalay<br />

Nay Pyi<br />

Taw<br />

ANDAMAN<br />

ISLANDS<br />

(INDIA)<br />

Andaman<br />

Sea<br />

India (5)<br />

Ulaanbaatar<br />

Hanoi<br />

LAOS<br />

THAILAND<br />

Phnom<br />

Penh<br />

Gulf of<br />

Thailand<br />

Vikas Ranjan,<br />

25 November<br />

Jagjit Saikia,<br />

20 November<br />

Javed Ahmed Mir,<br />

13 August<br />

Mohammed Muslimuddin,<br />

1 April<br />

Ashok Sodhi,<br />

11 May<br />

Guangzhou<br />

Shantou<br />

Nanning<br />

Zhanjiang<br />

Haiphong<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Macau S.A.R.<br />

S.A.R.<br />

Gulf of<br />

Tonkin<br />

CAMBODIA<br />

VIETNAM<br />

Christmas Island<br />

South China<br />

Sea<br />

Bandar Seri<br />

Begawan<br />

Medan<br />

Kuala<br />

Lumpur<br />

BRUNEI<br />

Pekanbaru<br />

M A L A Y S I A<br />

Singapore<br />

SINGAPORE<br />

Padang<br />

Pontianak<br />

Samarinda<br />

Thailand (3)<br />

Taiwan<br />

Kao-hsiung<br />

Luzon<br />

Strait<br />

Jaruek Rangcharoen,<br />

27 September<br />

Chalee Boonsawat,<br />

21 August<br />

Athiwat Chaiyanurat,<br />

1 August<br />

Celebes Sea<br />

Okhotsk<br />

Baotou<br />

Lanzhou<br />

Beijing<br />

NORTH KOREA Sea of<br />

Datong<br />

Tianjin<br />

Pyongyang Japan<br />

Shijiazhuang<br />

Dalian<br />

Taiyuan<br />

Yantai Seoul<br />

Zibo<br />

SOUTH<br />

Jinan<br />

KOREA<br />

Qingdao Yellow<br />

Zhengzhou<br />

Pusan<br />

Nagoya<br />

Sea<br />

Hiroshima<br />

Ōsaka<br />

Xi'an<br />

Fukuoka<br />

Nanjing Nantong<br />

Chengdu<br />

Wuhan<br />

Hefei<br />

Hangzhou<br />

Shanghai<br />

Chongqing<br />

Changsha<br />

Ningbo<br />

Nanchang<br />

East China<br />

Sea<br />

Chiang<br />

Mai<br />

Chita<br />

Vientiane<br />

Bangkok<br />

Kunming<br />

Palembang<br />

Guiyang<br />

Da Nang<br />

Hainan<br />

Dao<br />

Ho Chi Minh<br />

City<br />

SPRATLY<br />

ISLANDS<br />

Changchun<br />

Harbin<br />

Fuzhou<br />

Jilin<br />

Shenyang<br />

Xiamen<br />

PARACEL<br />

ISLANDS<br />

Banjarmasin<br />

Philippine<br />

Sea<br />

PHILIPPINES<br />

Banda Sea<br />

Ti<br />

JAPAN<br />

I N D O N E S I A<br />

Tanjungkarang-<br />

Java Sea<br />

Telukbetung Jakarta<br />

Makassar<br />

Bandung<br />

Semarang Surabaya<br />

Malang<br />

Denpasar<br />

Taipei<br />

Khabarovsk<br />

Manila<br />

Zamboanga<br />

Vladivostok<br />

Okinawa<br />

U<br />

R Y<br />

K<br />

U<br />

Y<br />

Cebu<br />

Sakhalin<br />

S<br />

I<br />

D<br />

S<br />

N<br />

A<br />

L<br />

Dili<br />

( JAP AN )<br />

Davao<br />

TIMOR-LESTE<br />

Kupang<br />

Sapporo<br />

Tokyo<br />

(JAPAN)<br />

Melekeok<br />

Cambodia (1)<br />

Khim Sambo,<br />

11 July<br />

Yokohama<br />

N A M P O - S H O T O<br />

-<br />

-<br />

PALAU<br />

Arafura<br />

Sea<br />

Petropavlovsk-<br />

Kamchatskiy<br />

KURIL<br />

ISLANDS<br />

Occupied by the SOVIET UNION in 1945,<br />

administered by RUSSIA, claimed by JAPAN<br />

Northern<br />

Mariana<br />

Islands<br />

(U.S.)<br />

Jayapura<br />

Guam<br />

(U.S.)<br />

Saipan<br />

Hagåtña<br />

PAPUA<br />

NEW GUINEA<br />

Philippines (5)<br />

Leo Mila,<br />

2 December<br />

Aristeo Padrigao,<br />

17 November<br />

Dennis Cuesta,<br />

9 August<br />

Martin Roxas,<br />

7 August<br />

Benefredo Acabal,<br />

7 April<br />

N O R T H<br />

P A C I F I C<br />

O C E<br />

Marcus Island<br />

(JAPAN)<br />

U.S.<br />

Tropic<br />

FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA<br />

Port<br />

Moresby<br />

A L E U T I A N I S L A N<br />

Palikir<br />

Equato<br />

SOLOM<br />

ISL<br />

Honiara<br />

9

10<br />

Afghanistan by Naomi Hunt<br />

It has been seven years since the U.S.led<br />

invasion of Afghanistan, but journalism<br />

remains a more perilous profession<br />

than ever before. Three journalists were<br />

killed this year, fewer than in 2007, but<br />

that was partly because at least two additional<br />

attempts on journalists’ lives failed.<br />

In a year where two men were sentenced<br />

to 20 years in prison for publishing<br />

a Dari-language (Persian) version of<br />

the Quran, it is clear that fundamentalist<br />

Islamists in the Afghan government have<br />

exerted increasing control over media<br />

content and culture.<br />

Over the last year, suicide bombings<br />

killed one reporter and injured another.<br />

A Norwegian reporter for the Oslo newspaper<br />

Dagbladet was one of six victims in<br />

a 15 January suicide squad attack on a<br />

luxury Kabul hotel. He was shot and died<br />

while undergoing surgery. <strong>On</strong> 29 April,<br />

Australian journalist Paul Rafael was<br />

injured along with 32 others when a suicide<br />

bomber attacked members of an<br />

opium eradication team close to the border<br />

with Pakistan. Photographer Steve<br />

Du pont escaped unharmed. The Taliban<br />

claimed responsibility for both attacks.<br />

U.S. forces released Jawed Ahmad, al -<br />

so known as Javed Yazamy, of Canadian<br />

Television, in September, after he was<br />

held at Bagram Air Base for nearly a year.<br />

In February, Pentagon officials claimed<br />

Ahmad was an “unlawful enemy combatant”<br />

but never revealed any proof. Ah -<br />

mad was never charged with any crime<br />

and was, in his own words, “tortured and<br />

jailed for 11 months and 20 days for<br />

doing nothing.”<br />

A Norwegian reporter<br />

for the Oslo newspaper<br />

Dagbladet was one of<br />

six victims in a 15 January<br />

suicide squad attack<br />

on a luxury Kabul hotel<br />

Afghanistan’s media law prohibits the<br />

publication of anything that harms the<br />

“national interest” or that is an “affront to<br />

Islam,” provisions often used to suppress<br />

expression. <strong>On</strong> 22 January, an Islamic<br />

court sentenced journalism student<br />

Sayed Parwez Kambakhsh to death for<br />

blasphemy, although the sentence was<br />

commuted this October to 20 years in<br />

prison following mounting international<br />

pressure.<br />

Kambakhsh was first arrested in Oc -<br />

tober 2007 for distributing allegedly anti-<br />

Islamic literature. He is the brother of<br />

prominent journalist Sayed Zaqub Ibra -<br />

himi, frequently under attack for criticizing<br />

local officials and warlords. Kam -<br />

bakhsh claims that he was tortured into<br />

signing a confession of apostasy (rejection<br />

of Islam). Also, the prosecution’s key<br />

witness admitted in court that officials<br />

had threatened to detain his family unless<br />

he made a statement against Kambakhsh.<br />

The Council of Ulemas and the information<br />

and culture ministry took steps<br />

to ban“un-Islamic” television shows. In<br />

March, the information ministry issued a<br />

statement condemning a programme on<br />

Tolo TV that showed men and women<br />

dancing together, which was allegedly<br />

“against the beliefs and traditions of Af -<br />

ghanistan’s Islamic society.” The next day,<br />

they ordered that three TV shows be re -<br />

moved from programming by 14 April.<br />

<strong>On</strong> 31 March, the lower house of parliament<br />

(Wolesi Jirga) adopted a resolution<br />

Afghan journalists hold a poster with a picture of the late Naqshbandi during a protest in front of the Afghan parliament in Kabul. (Reuters/Goran Tomasevic)

Afghans hold a demonstration against<br />

Perwiz Kambakhsh's death sentence<br />

in Kabul. (Reuters/Ahmad Masood)<br />

ordering that “sensual” images no longer<br />

appear in the media, adding that foreign<br />

dancers no longer be invited into the<br />

country.<br />

This move signals a distressing return<br />

to the repressive conditions under Tali -<br />

ban rule, and parallels Taliban decrees in<br />

areas where some of their number maintain<br />

authority today. In Mirali, located in<br />

Pakistan’s Tribal Area, vendors were or -<br />

dered on 12 March to stop selling two<br />

daily newspapers, Aaj Kal and Waqt, as<br />

they allegedly contained “un-Islamic and<br />

immoral photographs of women.”<br />

Taliban-era conceptions<br />

of gender roles incite frequent<br />

attacks on women<br />

who work alongside men<br />

The Taliban also killed BBC and Pajh -<br />

wok reporter Abdul Samad Rohani, who<br />

disappeared after his vehicle was stopped<br />

by armed men in Lashkar Gah. Rohani<br />

was found dead the next day, his body<br />

riddled with bullet holes and signs of torture.<br />

As head of the BBC’s Pashtu service<br />

in Helmand province, Rohani had repor -<br />

tedly received threats from a local chief<br />

who accused him of “boycotting” news<br />

put out by the Taliban.<br />

Taliban-era conceptions of gender ro -<br />

les incite frequent attacks on women who<br />

work alongside men. <strong>On</strong> 5 June, the family<br />

and friends of murdered journalist<br />

Zakia Zaki inaugurated a culture centre<br />

in her honour in Jabalussaraj. The foun -<br />

der of Sada-i-Sulh (Peace Radio) was shot<br />

to death in June 2007. Six suspects were<br />

detained and later released. Zaki’s family<br />

and colleagues believe that her killer is an<br />

influential local warlord. The failure to<br />

prosecute any suspects has been especially<br />

devastating for female journalists.<br />

<strong>On</strong> 6 and11 April, grenades were<br />

thrown into the home of Radio Faryad’s<br />

deputy editor-in-chief Khadija Ahadi.<br />

There were no casualties. Ahadi, whose<br />

talk show addresses social and political<br />

issues, says she was targeted for working<br />

with men. She has since quit her job. <strong>On</strong><br />

15 May, Nilofar Habibi, a presenter for<br />

Heart TV, was stabbed at home but survived.<br />

She subsequently left her post.<br />

Journalist Jameela Rishteen Qadiry, of<br />

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, reported<br />

that she received numerous anonymous<br />

death threats over the telephone in June.<br />

In late September, the owner and chief<br />

editor of Radio Quyash, Rona Shirzai,<br />

received threats from Governer Abdul<br />

Haq Shafaq warning her that if she does<br />

not obey his orders, her station might be<br />

shut down and her life could be at risk.<br />

News sources report that Shafaq has as -<br />

signed a two-person team to monitor<br />

Shirzai’s station.<br />

The year ended with a spate of abductions<br />

by Taliban and other insurgent<br />

forces, although the journalists were all<br />

later released. Mellissa Fung, a Canadian<br />

Broadcasting Corporation journalist, was<br />

kidnapped outside Kabul on 12 October,<br />

Afghanistan in Brief:<br />

and held blindfolded in a cave for 28<br />

days. Her “fixer” and her driver, brothers<br />

Shokoor and Qaem Feroz, were detained<br />

by Afghan security forces after they re -<br />

ported Fung’s abduction, but were later<br />

also released.<br />

Dutch reporter Joanie de Rijke was<br />

also abducted near Kabul in November,<br />

while working on a story for a Belgian<br />

magazine. She was freed a week later. Da -<br />

wa Khan Menapal of Radio Free Europe/<br />

Radio Liberty and Aziz Popal, of a Kan -<br />

dahar television station, were abducted<br />

by Taliban forces on 26 November as they<br />

were driving toward Kandahar, and re -<br />

leased after three days.<br />

Recommendations<br />

Abandon use of religious legislation<br />

(punishing heresy, apostasy, insults<br />

to Islam or the Prophet, etc.) for<br />

repression of the press.<br />

Obtain a commitment from all parties<br />

to the conflict to respect the right of<br />

journalists to practice their profession.<br />

Protect and promote women journalists<br />

and their work.<br />

Population: 32.7 million<br />

Domestic Overview: Hamid Karzai, the country’s first democraticallyelected<br />

president, was inaugurated for a five-year term in December<br />

2004. The country’s National Assembly consists of the “Wolesi Jirga”<br />

(lower house) and the “Meshrano Jirga” (upper house), the latter of which<br />

is elected by provincial councils and reserved presidential appointments.<br />

It was inaugurated in December 2005.<br />

The elections followed the Taliban’s expulsion from power by U.S.-led<br />

NATO forces in 2001. The ultra-conservative, mainly Pashtun Taliban<br />

seized control of Kabul in 1996 after twenty years of armed conflict,<br />

first aiding in the fight against Soviet forces and later beating out other<br />

factions and warlords for control of the state.<br />

Today, lack of infrastructure and continual assaults by various groups of<br />

armed insurgents challenge the new government’s ability to rule beyond<br />

the borders of the capital. The Taliban are now regrouping and exercise<br />

control over some areas in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region.<br />

Beyond Borders: Afghanistan’s diplomatic relations with the international<br />

community has grown since the fall of the Taliban. Its six neighbours have<br />

pledged to respect the country’s independence and territorial integrity,<br />

and it has sought increased economic cooperation with them.<br />

The government still relies heavily on international aid, including for<br />

purposes of providing social services to its citizens. Troublingly, Afghanistan<br />

is again the world’s largest exporter of opium and heroin.<br />

11

12<br />

Bangladesh by Barbara Trionfi<br />

Campaign posters hang above a street in Dhaka in the run-up to the landmark elections<br />

(Reuters/Andrew Biraj)<br />

Bangladesh in Brief:<br />

Population: 153 million<br />

Domestic Overview: Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan<br />

in 1971. After 15 years of military rule, democracy was restored in 1990.<br />

Bangladesh has a parliamentary democracy based on universal suffrage.<br />

The 13th amendment (1996) of the constitution provides for the organisation<br />

of general elections by a non-partisan caretaker government.<br />

In January 2007, following weeks of turmoil ahead of parliamentary<br />

elections, the caretaker government postponed the election and declared<br />

a state of emergency, which was eventually lifted in December 2008.<br />

Beyond Borders: Bangladesh holds good relations with India, Pakistan,<br />

China and other South Asian counties, as well as Russia. Bangladesh<br />

has been very active within the United Nations and the South Asian<br />

Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).<br />

The lifting of the state of emergency in<br />

Bangladesh on 17 December, ahead<br />

of the 29 December national elections,<br />

marked a hopeful development in a country<br />

that had been ruled by a caretaker<br />

administration nominated to lead the<br />

country to elections. The elections themselves,<br />

originally scheduled for January<br />

2007, were repeatedly postponed after<br />

widespread violence in the run-up to elections<br />

that same month led to the enforcement<br />

of the emergency law.<br />

Sheik Hasina, head of the Awami Lea -<br />

gue party, assured an IPI delegation that<br />

visited Bangladesh in early De cember that<br />

she was committed to media freedom.<br />

However, even after his party’s electoral<br />

victory on 29 December, concerns remain<br />

that the restoration of the two-party system<br />

in Bangladesh might in crease the an -<br />

tagonism between the political parties and<br />

the Bangladeshi media that are greatly<br />

polarized along political lines.<br />

Journalists covering<br />

corruption remained<br />

at risk of harassment<br />

and even torture<br />

Journalists covering corruption re -<br />

mained at risk of harassment and even<br />

torture. In March, Rabiul Islam, a journalist<br />

for The Daily Sunshine, a Banglalanguage<br />

newspaper, was arrested, as saul -<br />

ted and dragged to a police station. He<br />

was detained for 12 hours and accused of<br />

participating in a robbery, but released<br />

after the victim denied the journalist was<br />

involved in the offence. Rabiul has repeatedly<br />

written about corruption and other<br />

transgressions by the police force. In a<br />

show of solidarity, throughout his detention,<br />

a fellow journalist who happened to<br />

be at the police station re mained there to<br />

ensure his colleague was not harmed. In<br />

addition, senior journalists contacted the<br />

station to inquire about Rabiul’s arrest.<br />

The trial of journalist Jahangir Alam<br />

Akash, charged with extortion, served as<br />

a reminder of the real threat of such mistreatment.<br />

Akash, who works for both a<br />

daily and a television channel, was arrested<br />

in late 2007 after being accused of ex -<br />

tortion. He was detained for four weeks,<br />

and allegedly tortured by the Rapid Ac -<br />

tion Battalion (RAB) and the local police<br />

during this time. In 2008, his trial caused<br />

concern, with the prosecution accused of

guiding its witnesses and Akash’s request<br />

for a hearing deferment denied, even<br />

though the journalist’s main defence<br />

coun sel was unavailable.<br />

Akash was not the only journalist to<br />

allege such mistreatment. A report relea -<br />

sed in 2008 by Odhikar, a human rights<br />

organization, concluded that Noor Ah -<br />

med, editor-in-chief of the Dainik Sylhet<br />

Protidin and secretary general of the Syl -<br />

het <strong>Press</strong> Club, was detained by members<br />

of the RAB in 2007, and tortured. Ac -<br />

cused of extortion, Noor Ahmed alleges<br />

that he was repeatedly beaten with a<br />

stick, and ultimately signed a statement<br />

he could no longer read. Noor Ahmed<br />

had been investigating both the RAB and<br />

a local police inspector regarding possible<br />

corruption.<br />

Bangladeshi editors joined together<br />

for a unified call for the release of imprisoned<br />

editor Mohammad Atiqullah Khan<br />

Masud in September. IPI’s Justice Denied<br />

Campaign calls attention to the fate of<br />

Atiqullah Khan, editor of the daily<br />

Janakantha, arrested without warrant in<br />

March 2007 under the Emergency Po -<br />

wers Rules. Atiqullah Khan, an outspoken<br />

advocate of press freedom, faces a<br />

plethora of charges. The editors’ appeal<br />

for his release, supported by editors of the<br />

country’s 14 national dailies, emphasised<br />

Atiqullah Khan’s deteriorating health and<br />

the destabilizing effect of his incarceration<br />

on his newspaper’s already precarious<br />

financial situation.<br />

Bangladesh’s media environment this<br />

year was also affected by legislative developments.<br />

A controversial counterterrorism<br />

ordinance was adopted by the military-backed<br />

interim government in June.<br />

It was criticized both for being approved<br />

without public hearings, and for containing<br />

provisions susceptible to abuse. For<br />

example, terrorist acts were so broadly<br />

de fined as to include mere property cri -<br />

mes. In addition, the law introduced cri -<br />

minal penalties for speech intended to<br />

“support or bolster” the activities of a<br />

banned organization, with no requirement<br />

that incitement of criminal conduct<br />

is demonstrated.<br />

The new Right to Information law<br />

provided at least partly positive news,<br />

though many considered it insufficient.<br />

The law, approved by the advisers to the<br />

interim administration in September,<br />

was published in the official Bangladesh<br />

Gazette on 20 October. It was lauded for<br />

Bangladesh Awami League President<br />

and former PM Sheik Hasina<br />

(Reuters/Andrew Biraj)<br />

applying broadly to all information held<br />

by all public bodies, but the press freedom<br />

organisation Article 19 noted several<br />

deficiencies. In particular, the organization<br />

voiced concern regarding the ma -<br />

ny available exemptions, with as many as<br />

20 instances permitting request denials,<br />

including cases of corruption. The law al -<br />

so failed to protect good-faith disclosures.<br />

Towards the end of the year, all attention<br />

focussed on the landmark elections<br />

held on 29 December. An IPI mission<br />

that travelled to Dhaka from 27 Novem -<br />

ber to 2 December elicited commitments<br />

to an open media environment during<br />

elections from the main political parties,<br />

the Interim Administration and the<br />

Election Commission. Furthermore, representatives<br />

of the political parties that<br />

met with the IPI mission pledged to<br />

investigate the killings of more than a<br />

dozen journalists.<br />

Recommendations<br />

End impunity in the crimes against<br />

journalists<br />

Bring Bangladeshi laws in line<br />

with international standards<br />

on press freedom<br />

Enact a broadcasting law including<br />

provisions supporting media freedom,<br />

as well as a suitable commitment<br />

to public service<br />

Mission<br />

<strong>Press</strong> Freedom in Bangladesh<br />

From 27 November to 2 December<br />

2008, IPI conducted a high-level<br />

mis sion to Dhaka, Bangladesh to assess<br />

the country’s media environment ahead<br />

of the 29 December National Elections,<br />

as well as to elicit commitments from the<br />

heads of the two main political parties to<br />

support the right of journalists to report<br />

on the general elections without harassment<br />

or interference.<br />

The mission included IPI Director<br />

David Dadge; Owais Aslam Ali, Sec re ta -<br />

ry General of the Pakistan <strong>Press</strong> Foun d -<br />

ation (PPF) and Chairman of Pakistan<br />

<strong>Press</strong> <strong>International</strong> (PPI), Karachi; and<br />

Padma Singh Karki, Chairman of the IPI<br />

Nepal National Committee and editor<br />

and publisher of the Gatibidhi Weekly in<br />

Kathmandu. Bulbul Monjurul Ahsan,<br />

Head of News and Current Affairs at<br />

ATN Bangla and Executive Director of<br />

Media Watch, Bangladesh, was the local<br />

coordinator for the mission.<br />

Perpetrators of crimes<br />

against journalists are<br />

gene rally not prosecuted<br />

and the authorities<br />

do not seem to take the<br />

cases seriously<br />

The members of the IPI mission met<br />

with journalists, editors and media owners<br />

as well as with the head of the Awami<br />

League, leaders of the Bangladesh Natio -<br />

n alist Party (BNP), the Chief Advisor to<br />

the Interim Government, the Directorate<br />

General of Forces Intelligence, the At -<br />

torney General, and the Chief Election<br />

Commissioner, among others.<br />

Meetings with Editors<br />

and Journalists<br />

<strong>On</strong>e of the main problems highlighted by<br />

journalists is that media outlets in Bang -<br />

ladesh are politically polarized, and tend<br />

to favour either the Awami League or the<br />

BNP, the two main political parties.<br />

Some journalists noted that they should<br />

attempt to bridge this divide by agreeing<br />

on best practices of journalism, rather<br />

than focussing on supporting particular<br />

political parties.<br />

Editors expressed concern about laws<br />

and practices that have a chilling effect<br />

on their ability to report on issues of public<br />

interest. Criminal defamation was spe -<br />

cifically mentioned as a problem.<br />

13

14<br />

Bangladesh's Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina meets with the IPI Mission: IPI Director David Dadge, PPF Secretary<br />

General Owais Aslam Ali, IPI Nepal National Committee Chairman Padma Singh Karki (left to right)”<br />

It was noted that journalists are often<br />

ensnared in legal cases and accused of<br />

extortion. It is widely believed that many<br />

of the cases are triggered by reports that<br />

offend politicians and the authorities.<br />

Impunity was identified as a major<br />

prob lem. Perpetrators of crimes against<br />

journalists are generally not prosecuted<br />

and the authorities do not seem to take<br />

the cases seriously. Particularly in rural<br />

areas, some journalists complained that<br />

they have been harassed, intimidated and<br />

even tortured by the Rapid Action Batal -<br />

lion (RAB), the elite anti-crime force<br />

consisting of members of the Army, the<br />

Navy, the Air Force and the Police.<br />

The need to promote investigative<br />

jour nalism was also highlighted. How -<br />

ever, the recently passed right to information<br />

law does not provide enough guarantees<br />

for accessing information of public<br />

interest.<br />

Meeting with Sheikh Hasina,<br />

Head of the Awami League<br />

Sheikh Hasina stressed her commitment<br />

to press freedom during the elections.<br />

Sheikh Hasina acknowledged that freedom<br />

of expression is necessary if journalists<br />

are to play a vital role in supporting<br />

democracy and secularism, and said that<br />

journalists in Bangladesh enjoy full freedom<br />

of expression. She recognized, however,<br />

that the murder of journalists is a<br />

problem that affects the whole society.<br />

She also said that the Awami League was<br />

prepared to review the cases of murdered<br />

journalists as well as the case of imprisoned<br />

journalist Atiqullah Khan.<br />

Finally, Sheikh Hasina also highlighted<br />

the importance of professional training<br />

for journalists.<br />

Meeting with representatives<br />

of the Bangladesh National Party<br />

(BNP)<br />

BNP representatives also expressed concern<br />

about the media’s ability to report on<br />

the elections, given the Election Com -<br />

mission’s efforts to ensure that the commission<br />

is the only body allowed to re port<br />

the results after they are communicated<br />

by the returning officers in the districts.<br />

BNP representatives condemned the<br />

use of torture by the army. They also<br />

noted that they want “all murders to be<br />

properly investigated”, including those of<br />

journalists.<br />

Meeting with Dr. Fakhruddin<br />

Ahmad, Chief Advisor of the<br />

Interim Administration<br />

Responding to IPI’s concerns about the<br />

Emergency Power Rules (EPR), the Chief<br />

Adviser said that, while these include regulations<br />

that might affect the media,<br />

these laws have not been applied to limit<br />

media freedom. (This view was actually<br />

shared by some of the editors and journalists<br />

with whom the IPI delegation<br />

met). The Interim Administration has<br />

received no complaints from representatives<br />

of the media in this regard. He also<br />

indicated that the EPR will be lifted<br />

within a reasonable time.<br />

Meeting with Major General<br />

Golam Kader, Director General<br />

of the Directorate General<br />

of Forces Intelligence<br />

Addressing IPI’s concerns about attacks<br />

against journalists at the hands of the<br />

RAB and army, Major General Golam<br />

Kader responded that he could not vouch<br />

for the entire army, but stated that where<br />

cases of journalists tortured by the army<br />

have “surfaced”, the responsible individuals<br />

have been punished.<br />

Recommendations<br />

Based on its findings during the mission,<br />

IPI issued preliminary recommendations<br />

aimed at improving Bangladesh’s<br />

media environment. These called for:<br />

Investigating all attacks on journalists<br />

and continuing investigations into all<br />

cases of murdered journalists<br />

Ensuring all Bangladeshi laws meet<br />

international standards on press<br />

freedom and are in line with the<br />

spirit and intent of Article 39 of the<br />

Bangladeshi Constitution<br />

Enactment of a broadcasting law in<br />

line with international standards and<br />

containing provisions supporting freedom<br />

of the press, as well as a suitable<br />

commitment to public service<br />

The immediate release of imprisoned<br />

Janakantha editor and publisher<br />

Mohammad Atiqullah Khan Masud<br />

Allowing the media to report free of<br />

all attempts to influence this reporting<br />

Expressions of solidarity among the<br />

media in condemning press freedom<br />

violations.

Mohammad Atiqullah Khan Masud,<br />

editor and publisher of the national<br />

Bengali-language daily, Janakantha<br />

(“The People’s Voice”), was arrested on<br />

7 March 2007 without warrant under<br />

section 16 of Bangladesh’s Emergency<br />

Powers Rules 2007.<br />

Troops stormed Atiqullah Khan’s of -<br />

fice and, after arresting him, searched his<br />

office and his home. Two days later,<br />

police brought charges of “corruption”,<br />

“criminal activities”, and “tarnishing the<br />

image of the country” against him. Ati -<br />

qullah Khan, who requested but was de -<br />

nied bail, has been held in Dhaka Central<br />

Prison ever since.<br />

Atiqullah Khan was<br />

one of several journalists<br />

and editors who, in January<br />

2007, urged the newlyappointed<br />

interim government<br />

to take a clear stand<br />

in favour of press freedom<br />

and against censorship<br />

Atiqullah Khan was one of several<br />

jour nalists and editors who, in January<br />

2007, urged the newly-appointed interim<br />

government to take a clear stand in fa -<br />

vour of press freedom and against censorship.<br />

The daily Janakantha, one of Bang -<br />

ladesh’s leading newspapers, is known for<br />

its uncompromising stance on press freedom<br />

and has always tried to expose press<br />

freedom violations. During the past<br />

Justice Denied<br />

The Case of<br />

Mohammad Atiqullah<br />

Khan Masud<br />

Mohammad Atiqullah Khan Masud<br />

editor and publisher of the national daily Janakantha<br />

years, multiple physical attacks and other<br />

forms of harassment have been carried<br />

out against Janakantha’s journalists.<br />

As of October 2008, Atiqullah Khan<br />

has faced a litany of charges, and has been<br />

sentenced to a total of 48 years of imprisonment<br />

in six separate cases. Sentences of<br />

seven years were imposed on Atiqullah<br />

Khan on five separate occasions between<br />

March and May of 2008, all based on<br />

similar charges of fraud. In addition, on 3<br />

April, he was sentenced to 13 years in<br />

prison for amassing illegal wealth and<br />

hiding assets in his wealth statement submitted<br />

to the Anti-Corruption Commis -<br />

sion (ACC).<br />

<strong>On</strong> 19 September 2008, the editors of<br />

Bangladesh’s 14 national dailies issued a<br />

statement, widely reported on by the<br />

country’s media, calling for Atiqullah<br />

Khan’s release. In the meantime, dismal<br />

prison conditions have strongly affected<br />

his health, and he has been suffering<br />

from neurological problems, heart disease,<br />

intestinal disorder, kidney trouble,<br />

and eye problems. Atiqullah Khan is currently<br />

under treatment at Bangabandhu<br />

Sheikh Mujib Medical University Hospi -<br />

tal. His continued imprisonment has also<br />

put Janakantha in peril by further destabilising<br />

the newspaper’s already precarious<br />

financial situation.<br />

Timeline<br />

November 2008<br />

IPI launches campaign against<br />

imprisonment of Atiqullah Khan<br />

19 September 2008<br />

The editors of Bangladesh’s<br />

14 national dailies issue a<br />

statement calling for Atiqullah<br />

Khan’s release<br />

27 April, 14 May 2007<br />

In two different cases, Atiqullah<br />

Khan is sentenced to 14 years<br />

imprisonment based on fraud<br />

convictions<br />

3 April 2007<br />

Atiqullah Khan is sentenced<br />

to 13 years imprisonment for<br />

amassing illegal wealth and<br />

hiding assets in his wealth<br />

statement, which he had to<br />

submit to the Anti-Corruption<br />

Commission (ACC) from prison<br />

6, 9, 20 March 2007<br />

Atiqullah Khan is sentenced<br />

by the “Special Tribunal” to<br />

imprisonment of seven years<br />

each in three different cases<br />

involving charges of fraud<br />

7 March 2007<br />

Atiqullah Khan is arrested<br />

without warrant under Section<br />

16 of Bangla-desh’s Emergency<br />

Powers Rules 2007<br />

15

16<br />

Bhutan by Naomi Hunt<br />

People walk down a street beside a portrait of<br />

Wangchuck in Thimphu. (Reuters/Desmond Boylan)<br />

Bhutan in Brief<br />

Population: 682,000<br />

Domestic Overview: For centuries, Bhutan was culturally isolated by<br />

geographical chance and by choice. As a result, the tiny mountain country<br />

managed to preserve a thousand-year-old Tantric Buddhist tradition<br />

and a medieval social structure well into the Atomic Age.<br />

Bhutan has been united under the Wangchuck dynasty since 1885,<br />

and the monarchy is trusted and respected – Bhutan’s recent democratization<br />

was ordered by royal decree. King Jigme Singye Wangchuck<br />

created the guiding principle of “Gross National Happiness,” equating<br />

cultural protection with economic development.<br />

The King abdicated in favour of his son Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wang chuck<br />

in 2006. A draft constitution was published in 2005, and mock elections<br />

were held in 2007 so that the new electorate could practice voting.<br />

In the 1980s, thousands of ethnically Nepali Southern Bhutanese were<br />

harassed for practicing Hinduism and expressing their own culture.<br />

Ethnic violence erupted. Around 105,000 Southern Bhutanese have been<br />

living in UNHCR refugee camps in Nepal since that time, victims of one of<br />

the world’s most intractable and enduring refugee situations.<br />

Beyond Borders: As per the 1949 Treaty of Peace and Friendship, Bhutan’s<br />

foreign policy was “guided” by India until February 2007. Relations between<br />

the two nations remain close. Bhutan maintains friendly relations with the<br />

“Friends of Bhutan,” which include seven European countries and Japan,<br />

all of whom donate to social and development programmes. Bhutan is<br />

a member of the United Nations, but does not have diplomatic relations<br />

with any of the countries on the Security Council. Bhutan and Nepal are<br />

negotiating a solution to the refugee situation.<br />

Bhutan's King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck walks with Prime Minister Thinley during<br />

his coronation ceremony in Thimphu. (Reuters/Desmond Boylan)<br />

In March, Bhutan held its first ever legislative<br />

elections. The Bhutan Har mo -<br />

ny Party swept to power with 44 of 47<br />

seats, and the country’s first constitution<br />

was adopted by the new parliament in<br />

July. Bhutan is now a democracy, or ra -<br />

ther, a constitutional monarchy. The king<br />

and the Je Khempo, the spiritual head of<br />

Bhutan, are retained as sacrosanct leaders<br />

and guiding lights in a Buddhist country.<br />

The new constitution guarantees Bhu -<br />

tanese citizens freedom of speech, opinion<br />

and expression (Article 7.2), freedom<br />

of the press, radio and television and<br />

other forms of electronic dissemination<br />

of information (7.4), and the right to<br />

information. These broad rights were<br />

welcomed by observers; however, they are<br />

mitigated by the stipulation that the State<br />

can restrict these rights by law under certain<br />

circumstances. These circumstances<br />

are equally broad, and include “the interests<br />

of the sovereignty, security, unity and<br />

integrity of Bhutan” and “the interests of<br />

peace, stability and well-being of the na -<br />

tion,” amongst others.<br />

This year, journalists reporting from<br />

refugee camps in Nepal reportedly re -<br />

ceived death threats from members of the<br />

Communist Party of Bhutan Marxist-<br />

Leninist-Maoist (CPB-MLM), which is

anned in Bhutan and also works from<br />

the Nepal camps. Members of the Bhu -<br />

tan News Service, which is run by the<br />

Association of <strong>Press</strong> Freedom Activists<br />

(APFA), a Bhutanese exile organisation,<br />

were accused of recording speeches and<br />

taking photographs at a CPB-MLM<br />

event. According to reports, reporters<br />

Ichha Poudel and Arjun Pradhan were<br />

threatened with death, expelled from the<br />

meeting, and followed home.<br />

The refugee situation<br />

is politically sensitive<br />

in Bhutan, and major<br />

media outlets tend to<br />

take a pro-government<br />

position on the issue<br />

The refugee situation is politically sensitive<br />

in Bhutan, and major media outlets<br />

reportedly tend to take a pro-government<br />

position on the issue. According to ob -<br />

servers, dissent and criticism are also pre -<br />

sent in the state-run and major media.<br />

However, the new constitution seems to<br />

encourage self-censorship, as the government<br />

is able to strip rights when it comes<br />

to matters of state “integrity.”<br />

Inside Bhutan, although media control<br />

remains tight, there have been positive<br />

signs that the press is beginning to<br />

diversify and strengthen. The first priva -<br />

tely-owned newspaper, the Bhutan Times,<br />

was launched in 2006, and followed<br />

shortly by the Bhutan Observer. The<br />

country’s first daily, Bhutan Today, hit the<br />

stands on 31 October. This year, the<br />

government, in conjunction with the<br />

Uni ted Nations Development Program -<br />

me (UNDP), ran a series of training sessions<br />

for journalists on the role of media<br />

in a free society and on how to cover<br />

women’s and children’s issues.<br />

Although media control<br />

remains tight, there have<br />

been positive signs that the<br />

press is beginning to diversify<br />

and strengthen<br />

Television, which only arrived in 1999<br />

(along with the Internet), can now be<br />

found in 28% of all households, over half<br />

of which have satellite access. After TV<br />

was introduced, the stations MTV and<br />

Fashion TV were removed, along with a<br />

channel called Ten Sports, which carries<br />

professional wrestling and was reportedly<br />

encouraging fighting among Bhutanese.<br />

<strong>On</strong>ly 3% of households own a computer,<br />

but access is generally unlimited, al -<br />

though, according to Freedom House,<br />

the Bhutan Times website was blocked for<br />

two months last year due to anti-government<br />

comments. Also according to Free -<br />

dom House, state-run broadcast media<br />

never carry opposition views, and access<br />

to cable television, which is uncensored,<br />

is limited by a high sales tax and other<br />

bureaucratic hurdles.<br />

This year, according to the press freedom<br />

blog, Media in Bhutan, private me -<br />

dia were denied access to a high-level<br />

meeting between Indian Prime Minister<br />

Dr. Manmohan Singh and the Bhutanese<br />

premier, Jigme Thinley. Reports say that<br />

while the state-run newspaper Kuensel<br />

and the state-run Bhutan Broadcasting<br />

Service (BBS) were permitted entry, along<br />

with a retinue of Indian journalists, re -<br />

porters from the private Bhutanese media<br />

were left out. The Bhutanese journalists<br />

reportedly issued a press release to the BBS<br />

and Kuensel about what had happen ed,<br />

but neither publication ran the story.<br />

In a state that has controlled, at every<br />

step, the modernization of Bhutanese so -<br />

ciety, it remains to be seen whether an<br />

unruly and outspoken press will be al low -<br />

ed to flourish. If so, Bhutan will be well<br />

on its way to achieving true democracy.<br />

Recommendations<br />

Remove laws that threaten free<br />

speech and the free press<br />

Stop censorship in all forms<br />

Train journalists in media account -<br />

ability and the role of media in<br />

democracies<br />

Burma (Myanmar)<br />

by Naomi Hunt<br />

A man stands beside a dead body found at a<br />

Cyclone Nargis-hit village in Bogalay. (Reuters)<br />

Increased censorship and repression<br />

spar ked by the failed Saffron Revo lu -<br />

tion of 2007 persisted into 2008 as the<br />

Burmese junta sought to avoid a repetition<br />

of the Buddist-led movement for<br />

greater freedom.<br />

Journalists Thet Zin and Sein Win<br />

Aung of the Myanmar Nation were arrested<br />

in February in connection with<br />

reporting they were doing on the government<br />

crackdown during the revolution.<br />

The ruling State Peace and Develop -<br />

ment Council (SPDC), headed by Gene -<br />

ral Than Shwe, called a 10 May referendum<br />

on a planned national constitution<br />

that human rights organisations derided<br />

as a sham, arguing that it would effectively<br />

entrench military control over Bur -<br />

mese government and society.<br />

Reporters Without Borders and the<br />

Burma Media Association reported that<br />

no Burmese media were allowed to publish<br />

dissenting views on the constitution.<br />

Instead, boilerplate articles drafted by<br />

officials were forced into state and private<br />

newspapers. Editors were also compelled<br />

to print pro-constitution campaign logos<br />

in prime advertising spots.<br />

Just days before the vote was scheduled,<br />

cyclone Nargis struck the Irrawaddy<br />

delta region, making international headlines<br />

and leaving tens of thousands dead<br />

17

18<br />

Protester from Burma holds portrait of democracy icon Aung as he takes part in peace march in New Delhi. (Reuters/Danish Ishmail)<br />

or missing. It was later reported that the<br />

Burmese authorities had received 48hour<br />

advance warning of the cyclone<br />

from Indian meteorologists, but didn’t<br />

transmit this information to residents.<br />

The disaster resulted in a near-total<br />