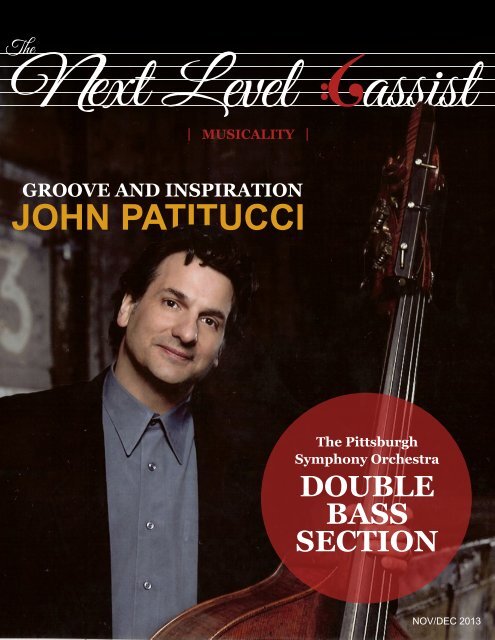

Next Level Bassist Musicality Issue

Articles by Sarah Hogan and John Patitucci, Spotlight on the Pittsburgh Symphony, Double Stop Strum by Ranaan Meyer

Articles by Sarah Hogan and John Patitucci, Spotlight on the Pittsburgh Symphony, Double Stop Strum by Ranaan Meyer

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

| musicality |<br />

Groove and inspiration<br />

John Patitucci<br />

The Pittsburgh<br />

Symphony Orchestra<br />

Double<br />

bass<br />

section<br />

NOV/DEC 2013

Contents<br />

Nov/Dec 2013<br />

Feature Story<br />

5 Spotlight: The Pittsburgh<br />

Symphony Orchestra<br />

7 Double Stop Strum<br />

ranaan meyer<br />

8 Musical Development<br />

Sarah Hogan<br />

12 Groove and Inspiration<br />

JOHN PATITUCCI<br />

Contributors<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

publisher / founder<br />

Brent Edmondson<br />

editor / sales<br />

Karen Han<br />

Layout designer<br />

2 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

Publisher’s Note<br />

Asking a musician to sit down and write about musicality...<br />

on paper it does not look like the epic task that it really is!<br />

Looking at that instruction, it seems like a job that every<br />

one of us, especially legendary players and teachers, should<br />

be able to do effortlessly. Try to define what musicality is,<br />

I challenge you! It is elusive and it changes every day. We<br />

can talk about why we play, or what we do to make Mozart<br />

sound different from Brahms, but we are only scratching the surface of what<br />

musicality really means to us.<br />

When I get up on stage with Time for Three, there is a sensation that washes<br />

over me which seems like a mixture of excitement, nerves, energy, confidence,<br />

fun, and many other things. I know that it is my job to find a way, through my<br />

bass, to send those wonderful and strange sensations to the people out in the<br />

audience. I am lucky to have a lot of opportunities to improvise in a Time for<br />

Three show, but there are great musicians in the pages to come who have their<br />

entire performance scripted and laid out in advance. Somehow, we are all carrying<br />

out this magical task night after night, moving people to feel things they<br />

were not aware of with vibrations and silence.<br />

I could not be more excited about the information that you are about to take<br />

in, the perspectives you will gain from reading about these titans of the bass.<br />

John Patitucci’s approach to the groove is something that no bass player should<br />

ever be without. Sarah Hogan provides a template for a life of musical growth<br />

and evolution. I hope that sharing the fun and inspiration of the members of<br />

the Pittsburgh Symphony bass section provides a motivation to any musician<br />

hoping to make it big and work with talented colleagues.<br />

At the end of the day, we are not aiming for careers as the best unaccompanied<br />

double bass player, we are preparing for careers of collaboration! <strong>Musicality</strong><br />

should color every single moment of your bass playing, whether it’s the high<br />

pressure of auditions or the backyard BBQ jam session. I encourage you to<br />

look past the competitive world of auditions and gigging, and put yourself in<br />

that moment when the lights go down and it is time to play. That is the world<br />

we all hope to live in, and I hope that the articles here make it that much more<br />

rewarding for you.<br />

- RANAAN MEYER<br />

johnson<br />

string instrument<br />

VIOLINS, VIOLAS, CELLOS, BASSES & GUITARS<br />

www.johnsonstring.com<br />

800-359-9351<br />

susanwilsonphoto.com<br />

THE BASS SHOP<br />

26 Fox Road<br />

Waltham, MA 02451<br />

sales • rentals • antique • contemporary • electrics<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

3

CARLO CARLETTI WILLIAM TARR PAUL TOENNIGES SAMUEL ALLEN DANIEL HACHEZ<br />

PIETRO MENEGHESSO LORENZO & THOMASSO CARCASSI PAUL CLAUDOT GIOVANNI LEONI<br />

ARMANDO PICCAGLIANI GAND & BERNARDEL STEFAN KRATTENMACHER JAMES COLE<br />

FRATELLI SIRLETTO ALASSANDRO CICILIATTI AKOS BALAZS SAMUEL SHEN G.B. CERUTI<br />

PAOLO ROBERTI CHRISTIAN PEDERSEN PAUL HART CHRISTOPHER SAVINO JAY HAIDE<br />

ANDREW CARRUTHERS GUNTER VON AUE BARANYAI GYORGY CARLO CARLETTI WILLIAM TARR<br />

PAUL TOENNIGES SAMUEL ALLEN DANIEL HACHEZ PIETRO MENEGHESSO LORENZO &<br />

THOMASSO CARCASSI PAUL CLAUDOT GIOVANNI LEONI ARMANDO PICCAGLIANI GAND<br />

& BERNARDEL STEFAN KRATTENMACHER JAMES COLE FRATELLI SIRLETTO ALASSANDRO<br />

roBertson reCital Hall<br />

2013 Bass ColleCtion<br />

partial<br />

4 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

www.RobertsonViolins.com<br />

Tel 800-284-6546 | 3201 Carlisle Blvd. NE | Albuquerque, NM USA 87110

The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra<br />

Double Bass Section<br />

For classical bass players, there are few pleasures greater than<br />

playing with dedicated and inspiring colleagues. Being able<br />

to surround yourself with great musicians is one of the great<br />

motivations of solitary practice. An amazing bass section can alter the<br />

sound of an entire orchestra. For the first Spotlight column of <strong>Next</strong><br />

<strong>Level</strong> <strong>Bassist</strong>, we’re very excited to recognize the Pittsburgh Symphony<br />

double bass section as one of the strongest and most impressive in the<br />

United States today. We spoke with the regular and substitute members<br />

of the section to get a 360 degree perspective on sitting in with<br />

one of the best bass sections around.<br />

The PSO section is an impressive array of veteran bass players of many<br />

of the nation’s great orchestras. Coming from legendary orchestras like<br />

the Detroit Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, and San Diego Symphony,<br />

every member of the section plays with both strength and wisdom.<br />

According to Principal <strong>Bassist</strong> Jeffrey Turner, “it is a daily privilege to<br />

get to work in a section filled with such wonderful bassists, musicians,<br />

and people. Every single member of our section is an asset<br />

to the orchestra.”<br />

One of the rare advantages possessed by the PSO is its relatively fresh<br />

bass player roster. Since his appointment to the orchestra, Mr. Turner<br />

has been present in the hiring of each other member of the bass<br />

section. Imagine being able to craft your own all-star team of players<br />

based on your experience and the incredible support of a great orchestra!<br />

Having a team made up of highly experienced members in the<br />

peak of their careers is the perfect environment to collaborate.<br />

“We all set good examples for each other,” says Turner. “Working in<br />

our section is one of the great joys of my life.” Section member John<br />

Moore likes to think of it as “driving a very smooth and powerful<br />

sports car.”<br />

It’s easy to hear this in the recent Manfred Honeck Mahler series by<br />

the orchestra, where the bass section shines through extremes of dynamics<br />

and color. “We play big and we play together” is the Pittsburgh<br />

Symphony motto, according to regular substitute Brandon McLean.<br />

“Dynamic range in this group is way beyond that of many other ensembles.”<br />

McLean’s first experience as a substitute underscores one of the unique<br />

qualities of the Pittsburgh Symphony itself. Mclean said his feedback<br />

from the section was “to feel free to play out and get into the sound<br />

of the section a bit more. They weren’t interested in someone coming<br />

in and just hiding within the group. That was after a week in which I<br />

was already convinced that I was playing as big and bold as I possibly<br />

could!”<br />

When you listen to a recording of the orchestra, the bass section has a<br />

presence that is only possible through total unanimity. It was surprising<br />

to find, when asked how they adapted to the playing style of the<br />

section, that each player approached the group with a highly individual<br />

voice. According to Jeff Turner, “I don’t like the word ‘blend.’ It<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

5

is essential that each player feel he or she is<br />

making an audible and meaningful musical<br />

contribution.” As John Moore puts it, “players<br />

will bring something out and the others will<br />

catch on and follow. There is almost never any<br />

discussion.” The excitement that comes from<br />

this spontaneous music making underscores<br />

the trust and confidence that runs through<br />

each member. As part of a profession where<br />

people may sit next to the same person for 30<br />

years, it’s remarkable to know that colleagues<br />

can still bring inspiration to the workplace<br />

every day.<br />

In an era of increasing financial difficulties<br />

and uncertainty in the nation’s orchestras,<br />

the Pittsburgh section remains excited and<br />

enthusiastic. According to Jennifer Godfrey, a<br />

frequent section guest, “each time I sub here,<br />

I wonder if I’ll be fired for smiling too much<br />

during rehearsals.” It’s this attitude of “professional<br />

playfulness” that gives each member a<br />

sense of ownership and pride. In professional<br />

music settings, it’s easy to feel like your voice<br />

isn’t being heard - in fact, in some groups this<br />

is almost the goal of the ensemble. Not so in<br />

Pittsburgh, according to Micah Howard: “We<br />

all give 100%. We have great respect for each<br />

other. We share ideas and grow musically<br />

together.” In fact, this was a response received<br />

from every member of the bass section, where<br />

collaboration far outranks ego.<br />

Speaking of Mahler, nearly every member of<br />

the bass section reported that their favorite<br />

repertoire to play was the big romantic works<br />

of Mahler and his contemporaries. Sure, it’s<br />

little surprise that musicians are attached to<br />

and affected by the emotional outpouring and<br />

total immersion of this composer, but it boils<br />

down to the musical philosophy of the bass<br />

section as described by Jennifer Godfrey:<br />

“To (F-ing) Rock It!” ■<br />

Selected viewing<br />

Complete performance of<br />

Mahler 5 with the Pittsburgh<br />

Symphony and Manfred Honeck<br />

at the Berlin Philharmonie<br />

(Great bass soli shot at 12:34!)<br />

http://www.youtube.com/<br />

watch?v=Rv6gKituIfY<br />

Mahler 2, Movement 1<br />

conducted by Sir Gilbert Levine<br />

(with an absolutely riveting opening<br />

passage by the bass section)<br />

http://www.youtube.com/<br />

watch?v=6C1htRMKtlQ<br />

Ein Heldenleben conducted<br />

by Manfred Honeck at the<br />

Berlin Philharmonie<br />

(the work begins at 23 minute mark)<br />

http://www.youtube.com/<br />

watch?v=yyeR-gPakWo<br />

Lemur Music<br />

“Everything for the Double Bass”<br />

Full Service Lutherie Shop, Bass<br />

Showroom, and On-Line Store<br />

Dozens of Basses, Strings,<br />

Bows, Rosins, Gig Bags,<br />

Stands, Accessories, Pickups,<br />

Speakers, Amps, Music &<br />

Recordings, plus hundreds of<br />

items you always dreamed of<br />

finding...all in one place.<br />

32238 Paseo Adelanto,<br />

San Juan Capistrano, CA<br />

92675<br />

lemur@lemurmusic.com<br />

800-246-BASS<br />

www.lemurmusic.com<br />

6 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

?# °<br />

¢ <br />

play arco or pizz.<br />

q = 186<br />

Double In Stop Fifths Strum<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

œ ¿ œ œ<br />

œ œJ<br />

œ œ<br />

œ œJ<br />

œ œ ¿ œ œ œ œ œ œ ¿ œ œ œ œ œ ¿ œ œ J<br />

œ œ J<br />

œ ¿ œ œ œ ¿ œ œ<br />

ü<br />

†<br />

repeat 3x<br />

16 mm total<br />

5<br />

?#<br />

œ ¿ œ œ J<br />

œ œ J<br />

œ ¿ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ<br />

œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

J<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

J<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

p<br />

œ œ<br />

œ<br />

9<br />

?#<br />

œ ¿ œ œ J<br />

œ œ J<br />

œ ¿ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

J<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

J<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

p p p<br />

œ œ<br />

œ<br />

œ œ œ œ<br />

œ œ<br />

13<br />

?#<br />

œ ¿ œ œ J<br />

œ œ J<br />

œ ¿ œ œ œ œ<br />

gliss.<br />

œ<br />

h<br />

h<br />

p p p<br />

œ ¿ œ œ œœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ j œ œ<br />

J<br />

17<br />

?#<br />

œ<br />

¿ œ œ J<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

J<br />

œ ¿ œ œ œ œ<br />

gliss.<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

¿ œ œ œJ œœ œ œ<br />

h<br />

h<br />

20<br />

?#<br />

p p p p<br />

œ œ<br />

œ<br />

œ œ œ œ œ œ<br />

œ<br />

Fine<br />

°<br />

¢ <br />

D7 A‹7 G<br />

∑ ∑ ∑ ∑<br />

repeat 3x<br />

16 mm total<br />

ü<br />

†<br />

D.C. al Fine<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

7

Musical<br />

Development<br />

By Sarah Hogan<br />

8 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

What does it mean to play musically? How does one become a<br />

musical player? Since music is an art, it is so widely subjective that it<br />

is hard to know the right answer. As a student, I remember being told<br />

to play something “more musically,” and going home and not getting it,<br />

and therefore not really working on it. This is what I have seen happen<br />

with my students, so I have really begun to think about a few things:<br />

How did I develop my own sense of musicality? And most importantly,<br />

how can I teach that?<br />

First and foremost, like most artists, this sense of being musical is<br />

constantly being developed. Also, as with other types of artists, it is the<br />

art itself that drives the quest. These days, listening and playing with my<br />

colleagues is what most inspires me and is what continues to drive me.<br />

After listening and thinking “that was freakin’ awesome!” I try to get<br />

down to the details of WHY it was awesome, and WHAT that person<br />

did technically to make it that way.<br />

First, let me just put on the record that I was a lucky bass kid. Thankfully,<br />

I had parents who listened to my high-energy and unrelenting strings<br />

teacher about me playing the bass and also about me needing lessons<br />

from the best teacher around. In her opinion, that was the former principal<br />

bassist of the St. Louis Symphony, Mr. Henry Loew. My parents<br />

drove me weekly to lessons with him, and to other various extra-curricular<br />

orchestra activities. For that, I am most grateful.<br />

Mr. Loew taught me many great things, but it was because of his enthusiasm<br />

and smile that I often think he could have taught me anything,<br />

and I would have been just as hooked. The most important thing he<br />

taught me about the bass was to always, always play everything “like you<br />

mean it.” Make music with everything. He taught me out of the Nanny<br />

etude book because, as he explained, I could learn the bass and make<br />

music at the same time. The melodies are fine, certainly better than other<br />

etude books, but he was able to improvise piano accompaniment that<br />

brought those exercises to life. I still remember which exercises I loved<br />

most, playing them over and over again even after we had long passed<br />

them. I regret that my piano skills are less than adequate because I can’t<br />

provide the same lively accompaniment for my students. I try to show<br />

them the music that can be made within each exercise or piece and hope<br />

that my excitement is just as contagious.<br />

I once heard someone say that all music making is just a creation of tension,<br />

and then finding a way to release it. I think there is some truth to<br />

this. I often think about a masterclass I was lucky enough to have with<br />

Mr. Ed Barker in which he diagrammed on a blackboard the dynamics<br />

of an excerpt. It is that kind of analytical approach I think of when<br />

finding this idea of creating and then releasing tension. Where does the<br />

height of the tension occur? Where is it released? Most importantly,<br />

what technically do you have to do to both build and then release it?<br />

For a concrete example, I have found this idea to be particularly evident<br />

in the first movement of the Eccles Sonata. In my opinion, each half<br />

of a movement has a clearly defined moment where the tension is at its<br />

highest (in this case coinciding with the high point in the range) and<br />

then is released. On a personal note, my favorite moment in the movement<br />

is when the second half starts in the major key. What a relief, and<br />

always bring a smile to my face. With my students, I try to highlight<br />

these moments, and what we can do to make them more evident to<br />

the listener.<br />

Another piece where I frequently find myself saying to my students,<br />

“You’re playing this like an etude. Make some music with it,” is the<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

9

Koussevitzky Concerto. I am always boggled when I have to<br />

say that in the first place, since I can’t remember NOT making<br />

music with it. I’m sure Mr. Loew said the same thing to<br />

me, which is why I remember the beautiful story he told me<br />

to conjure up an image so that I WOULD play it musically.<br />

He helped me realize the piece is a sad, angst filled love song<br />

that drives the melodies. This is another tool I try to teach<br />

my students - if the music inspires them to imagine a story<br />

“I find that singing a phrase can often<br />

help with the fluctuation of time that can<br />

be effective in creating a musical line.ˮ<br />

or an image, the musical point will be more clear. For lack<br />

of a better phrase, “Paint me a picture.”<br />

In my analytical view, there are a few big technical tools<br />

one can use to help create the above mentioned tension and<br />

pictures. Dynamics, the variance of tone, vibrato, and the<br />

fluctuation of time are a few techniques that we can use to<br />

help create a sense of music within a piece. Dynamics are a<br />

pretty cut and dry tool to use. Luckily, many composers and<br />

editors give us the general direction for these. For example,<br />

a change in dynamic can signal increasing or decreasing tension<br />

or the beginning of a new phrase. That is when those<br />

above mentioned diagrams can become particularly useful.<br />

Mapping out exactly what you as the musician are hoping to<br />

achieve as you change the “volume” level can be extremely<br />

helpful. The next and most important step is to find out if<br />

what you are doing is audible to the listener. This can be<br />

done most efficiently by recording yourself and finding out<br />

if what you are doing can be heard. In my experience, as the<br />

player you must always be more dramatic and exaggerated<br />

than you think with dynamics for them to be evident to<br />

the listener.<br />

Varying the tone you produce on the instrument can be<br />

quite helpful in creating a sense of musicality as well, and<br />

is often done in conjunction with dynamics. When I think<br />

about the point when the first movement of the Eccles Sonata<br />

goes from the minor into the major key, I think about<br />

warming up my tone. This is a great metaphor, playing<br />

something “warm” or “cold,” but what does it mean? In that<br />

case, when I go from minor to major, or cooler to warmer,<br />

not only does my dynamic increase to start the phrase, but I<br />

also am trying to use more bow, and more bow hair to create<br />

a fuller, rounder sound. In addition, it is important to think<br />

about playing the same dynamic with contrasting tones.<br />

You can play a passage forte in a myriad of ways. To play an<br />

aggressive forte sound, the player can create a harsher sound<br />

by playing closer to the bridge. To play a big, hearty Brahms<br />

passage, the player would think about using more bow and<br />

not playing quite as close to the bridge in order to find that<br />

sweet spot where the instrument sings. For the opening<br />

phrases of Mozart’s 35th Symphony, we want to create a forte<br />

sound that is strong, but somehow lighter than Brahms,<br />

most likely by playing with a bit less hair and slightly closer<br />

to the fingerboard. The same discussion can be had for all<br />

the different ways to play softly, with varying amounts of<br />

hair and bow speed.<br />

Vibrato is a great asset to us as musicians. I like to tell my<br />

students that using vibrato is like using glitter. You can use<br />

a little or a lot, in as many ways and colors are imaginable.<br />

Slow or fast, wide or narrow. Creeping in, or immediate.<br />

None or very intense. I truly started listening<br />

to vibrato when I was told mine sounded “odd.”<br />

I hadn’t given it much thought until that point. I<br />

thought bass vibrato was, well, bass vibrato. I try<br />

not to let my students fall into that hole, as well<br />

as not letting the cumbersome size of our instruments<br />

get in the way of our music. I often try<br />

to think of a singer or wind player playing the<br />

same melodic line, to make sure that a technical glitch on<br />

the bass isn’t getting in the way of my vibrato. For instance,<br />

if a note occurs most easily as a harmonic, that doesn’t mean<br />

the vibrato should stop or sound different when we land on<br />

it. In addition, shifting can also create problems for vibrato.<br />

It is important to remember that shifting and vibrato are two<br />

different motions and we can do them independently, and<br />

that shifting doesn’t require the vibrato to stop. Most importantly,<br />

I try to listen to other string players and how they use<br />

their vibrato to “decorate” their musical lines. When practicing<br />

the Vanhal Concerto, I think of listening to my friend<br />

play Mozart violin concerti. When practicing the Koussevitzky,<br />

I think of another playing the Elgar Cello Concerto. It<br />

is truly by listening to others play that I have learned how to<br />

enhance my vibrato to use the “glitter” appropriately.<br />

I find that singing a phrase can often help with the fluctuation<br />

of time that can be effective in creating a musical<br />

line. It was a friend of mine who plays the french horn who<br />

unknowingly taught me this technique through very thin<br />

practice room walls. If you can sing and conduct it, probably<br />

the acceleration or ritard you are trying to make will<br />

sound more organic. In the right context, it is appropriate<br />

for the musical line to push or pull, but most often we want<br />

to do that in a way that pleases the listener, rather than<br />

jars them. The Recitative excerpt from Beethoven’s Ninth<br />

Symphony is an excellent example of this. We all know that<br />

there are more ways than we can count to interpret this excerpt.<br />

When playing it in an audition, it is most important<br />

to play this excerpt musically, in a way that will please rather<br />

than raise eyebrows. The idea is that if you can conduct and<br />

sing this excerpt, it is more likely that the conductor and<br />

other musicians on the committee will be able to imagine<br />

doing the same while you are playing.<br />

It is the thrill of making music with my friends and colleagues<br />

that I find most exhilarating. We are bass players<br />

because we love to play with the whole orchestra and collaborate<br />

with our friends. So, listen to them and try to break<br />

down what it is they did that sent shivers down your back,<br />

and hopefully you will soon be doing the same. ■<br />

10 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

PHOTOGRAPHY: JEFF GRASS<br />

ORCHESTRAL INSTITUTE<br />

May 30 – June 28, 2014 | For college and young professional musicians (ages 18–30)<br />

All participants receive a fellowship covering tuition, housing, and meals.<br />

2014 REPERTOIRE HIGHLIGHTS<br />

Bartok | Suite from The Miraculous Mandarin<br />

Britten | Sinfonia da Requiem<br />

Brubeck | Travels in Time for Three<br />

Mahler | Symphony No. 2<br />

Nielsen | Symphony No. 4<br />

Shostakovich | Symphony No. 10<br />

Wagner | The Ring Without Words<br />

COnduCTORS<br />

Mei-Ann Chen<br />

Daniel Hege<br />

Franz Anton Krager<br />

Carlos Spierer<br />

GuEST ARTISTS<br />

Cynthia Clayton, soprano<br />

Melanie Sonnenberg, mezzo-soprano<br />

Participant Winner, Mitchell Young Artist Competition<br />

Time for Three<br />

Houston Symphony Chorus<br />

FACuLTy<br />

Violin<br />

Emanuel Borok<br />

Andrzej Grabiec<br />

Frank Huang<br />

Lucie Robert<br />

Leon Spierer*<br />

Kirsten Yon<br />

Jun Zuo<br />

Viola<br />

Wayne Brooks<br />

Helen Callus<br />

Susan Dubois<br />

SEASON<br />

Cello<br />

Norman Fischer<br />

Brinton Smith<br />

*<br />

Week 2 guest concertmaster<br />

Double Bass<br />

Paul Ellison<br />

Eric Larson<br />

Dennis Whittaker<br />

Flute<br />

Leone Buyse<br />

Aralee Dorough<br />

Oboe<br />

Robert Atherholt<br />

Anne Leek<br />

Clarinet<br />

Randall Griffin<br />

Michael Webster<br />

Bassoon<br />

Richard Beene<br />

Elise Wagner<br />

Horn<br />

Robert Johnson<br />

William VerMeulen<br />

Trumpet<br />

Mark Hughes<br />

Jim Vassallo<br />

Trombone<br />

Allen Barnhill<br />

Tuba<br />

David Kirk<br />

Harp<br />

Paula Page<br />

Percussion<br />

Ted Atkatz<br />

Matthew Strauss<br />

All programs, faculty and guests are subject to change.<br />

www.tmf.uh.edu<br />

UH is an EEO/AA institution<br />

Join today’s rising stars at the TMF 2014 Orchestral Institute<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST 11

John Patitucci<br />

Groove and Inspiration<br />

How does one begin to think musically? What is at the foundation<br />

of musicality? And how do we as bass players tap into that, especially<br />

when our role is most often to support other lines in the music?<br />

Sound<br />

Sound is the starting point of our whole discussion. If our sound isn’t<br />

beautiful and singing, then we’re going to have a hard time selling<br />

everything else. You need to tailor your sound to the music you’re<br />

making - you’ll have times you need to be robust and step out, and<br />

you’ll have times to be really intimate and quiet.<br />

I tell my students to write down what things make up a “beautiful<br />

sound” in their own opinions. Draw on singers and other instruments<br />

that have beautiful sounds and incorporate them into your bass sound.<br />

Think about what you want to sound like. A lot of people never even<br />

take the time to do that. They think it’s only in the strings or the setup,<br />

or “I’ll finally get that great bass and sound good.” It’s not about the<br />

right mic, or the right amp - it’s in your hands, your heart, your soul,<br />

your mind, your ears before it ever gets to your hands!<br />

A lot of this has to do with your ability to just pull sound out of the instrument.<br />

I always say, “Don’t go for expediency, go for sound.” If you<br />

have to shift to get the lyrical phrase you want, do that instead of going<br />

across the strings to make it easier. If you have to play rapidly, find the<br />

fingering that’s going to make it happen with a great tone! Learn all the<br />

different ways to finger things but make sure that sound is the first priority.<br />

If you’re playing in a group where you need to pull a big sound,<br />

you may need to bring the strings up to be able to pull a little harder,<br />

rather than going for the easy way out. Make all your decisions based<br />

on getting the most out of your instrument.<br />

Today, there is a big move in the direction of lower and lower string<br />

heights. I run into a lot of players whose setup is really low, and I have<br />

to ask them what would happen if they had to play really loud - the<br />

top just doesn’t vibrate as much with lower string heights, and with<br />

pizzicato it’s particularly hard to get that big sound. The sweet spot is<br />

different for every single bass out there too! Experiment at different<br />

heights and see how this affects the quality of your sound. Make the<br />

decision of how your bass should be set up on what your musical<br />

needs are - you should always be able to pull a robust sound no matter<br />

what - and find what makes you most capable of playing your best.<br />

I think any serious discussion of sound could take weeks, and it’s<br />

something that will need constant attention, especially as you grow<br />

more aware of rhythm and harmony. As bass players, it can be easy<br />

to lose sight of the fact that we are musicians first and foremost! The<br />

more aware you become of the total musical picture around you, the<br />

more decisions you’ll make about your sound. This is one of the most<br />

important perspectives I think a double bassist of any genre can adopt.<br />

Think like<br />

a composer<br />

It’s important for bass players to avoid getting too “into the bass” - one<br />

of the reasons we spend all this time practicing is to build our technique<br />

and to learn how to play anything we want. Technique isn’t just<br />

about speed, or about playing more notes faster. You need to have the<br />

taste to know when to use it, how to use it, and how to use it expressively<br />

rather than mechanically. There are a lot of people that can really<br />

get around the bass, but all the flexibility in the world doesn’t add up<br />

to anything if you can’t tell a story and move somebody. When you<br />

don’t concern yourself with executing notes, you can make choices<br />

and start to express ideas and feelings. We have such a great power as<br />

bassists - our input can change the direction of the music within one<br />

beat or one pitch. It’s quite a responsibility.<br />

12 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

This applies even in strictly classical music that’s all written down.<br />

Even with historic traditions and a lot of indications of how you<br />

should interpret a piece, you’ll have more success in those pieces if<br />

you’re aware of how your part fits into the greater whole in terms of<br />

rhythm and harmony. I think you play a lot differently if you know<br />

the colors that are being achieved by the whole ensemble, rather than<br />

focusing on trying to play the bass well.<br />

Rhythm and<br />

the groove<br />

One of our most important duties in every ensemble is to create,<br />

sustain, and control the rhythm of the music. I get my students to play<br />

some drums. I don’t care what kind of music you play, whether it’s<br />

in an orchestra, in chamber music, jazz, or funk - if you want to play<br />

music all the time, you need to spend some time playing percussion,<br />

where each limb physically keeps time. Too many musicians spend<br />

most of their lives inside their heads, playing too cerebrally. It’s important<br />

to have contact in your body with what rhythm is!<br />

There are different ways to give yourself accountability for rhythm.<br />

There’s the metronome of course, and setting it to pulse on different<br />

beats is a great start. Try setting it to play on every different beat in the<br />

bar. When you’ve mastered that, try to click once every two bars, every<br />

four bars, even once for a whole chorus of 12 bar blues! That’s a tough<br />

one, because you have to stay in the pocket with very little feedback or<br />

information. Playing along with records and working on drums can<br />

add to the depth of groove understanding.<br />

Dizzy Gillespie said in every style of music, there’s a quarter note.<br />

What defines the style and interpretation is what’s inside that quarter<br />

note. What’s the most important thing in that quarter note? In jazz, it’s<br />

a triplet, and you need to know that this reaches back to African 6/8<br />

rhythms. In my teaching, we talk about the abakua rhythm:<br />

Score<br />

Score<br />

6/8<br />

6/8<br />

Rhythmic<br />

Rythmic Independance<br />

Independence<br />

Exercise<br />

Exercise<br />

Danilo Perez<br />

Danilo Perez<br />

&<br />

8<br />

6<br />

CLAP<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ<br />

‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

J<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ<br />

‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

J<br />

.<br />

iano<br />

STEP<br />

Left Right<br />

?<br />

8<br />

6 j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

.<br />

5<br />

&<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ<br />

‰<br />

J œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ<br />

‰<br />

J œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

.<br />

9<br />

?<br />

&<br />

?<br />

13<br />

&<br />

‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰<br />

. œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ<br />

.<br />

‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j<br />

. œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ<br />

œ<br />

‰<br />

‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

J<br />

‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j<br />

‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

J<br />

‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ ‰<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j œ<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ<br />

‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰<br />

‰<br />

J œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰ j œ<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ<br />

J<br />

.<br />

.<br />

.<br />

4 3 4 3<br />

?<br />

.<br />

j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

j<br />

œ ‰ ‰ j œ ‰ ‰<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST 13

17<br />

&<br />

4 3 œ œ œ œ ‰ œ ‰ œ ‰ œ œ œ œ œ ‰ œ ‰ œ ‰ œ .<br />

4 3<br />

?<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ ‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ ‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ ‰<br />

œ ‰ œ ‰ œ ‰<br />

.<br />

Mastering an exercise like this is still only the<br />

tip of the iceberg, but it can begin to develop<br />

the internal rhythm that you really need<br />

to hold a groove. It has been my experience<br />

that players of all genres benefit from this.<br />

After all, if you go through your life learning<br />

incredibly complex concerti and sonatas, you<br />

might still get away without spending a lot of<br />

time on rhythm. When a great classical musician<br />

plays a Brandenburg Concerto, he or<br />

she aims to achieve a “swing” in that bubbly,<br />

dancing way that Bach is meant to be played.<br />

I think this is why jazz musicians are drawn<br />

to Bach, Mozart, Beethoven - these composers<br />

had a certain unmistakable rhythmic drive<br />

in their music. You have to be able to groove<br />

to play Mozart 40 in an audition!<br />

We’re talking about being able to stand alone<br />

and generate an unshakable rhythm independently,<br />

and it’s the calling card of every<br />

great musician out there. There are ways<br />

to test yourself. Record yourself playing an<br />

ostinato and check with the metronome<br />

throughout to see if you’re drifting. Play with<br />

other people and move through a variety of<br />

rhythmic feels - 2-step, walking, samba, tumbao<br />

- and ask them if they feel like they want<br />

to play along! If you can play a 2 bar phrase<br />

that makes people want to dance, you’re doing<br />

it right!<br />

You should endeavor to make a groove sustainable<br />

for a very very long period of time.<br />

In the cultures where jazz came from, like<br />

African and Caribbean music, musicians can<br />

keep inside the groove for hours at a time.<br />

Your attention span needs to grow, and you<br />

need to learn the concentration skills to remain<br />

fixated on a groove for a long time. I tell<br />

students if you can’t maintain a groove and<br />

make it feel incredible for 10 minutes, you<br />

don’t have it yet.<br />

When you really analyze the idea of groove,<br />

you find that it’s about sound…beauty and<br />

consistency of sound - if you can’t get that<br />

from the bow or from your fingers, then you<br />

won’t have the tools to play rhythms correctly.<br />

If you don’t have a consistent attack and contact<br />

point, your rhythm will suffer. The groove<br />

can get disrupted because you aren’t giving<br />

the downbeat its proper emphasis, or shaping<br />

the inner beats, or you’ll trip over a string<br />

crossing. Being able to create a groove is<br />

everything wrapped into one - it’s technique,<br />

rhythm, sound, emotion, concentration,<br />

focus, patience…<br />

Part of the time when I ask someone to play<br />

me a two bar pattern, he’ll start noodling.<br />

NOW<br />

AVAILABLE<br />

SOLO<br />

TUNING<br />

Strings Handmade in Germany<br />

Photo Credit © Pöllmann<br />

14 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

Bard College Conservatory of Music with the American Symphony Orchestra announces the<br />

american symphony orchestra<br />

Double Bass Scholarship<br />

A full merit scholarship covering tuition, room and board at the Bard Conservatory.<br />

Conservatory Double Bass Faculty<br />

Leigh Mesh<br />

Marji Danilow<br />

845-758-7604 bard.edu/conservatory conservatoryadmission@bard.edu<br />

What I want to hear is the different roles of the notes in different parts<br />

of the bar. (See example) There are lots of elements to that seemingly<br />

simple pattern. If you can’t create that sort of groove, you don’t have<br />

musicality yet!<br />

?<br />

4<br />

œ<br />

Call<br />

Response Repeat Repeat<br />

bœ<br />

j œ œ œ œ bœ<br />

j œ<br />

Once you have really crafted your internal rhythm, you can begin<br />

thinking about all the styles of music out there where your rhythm<br />

needs to be flexible. This can be classical music, or it can even be really<br />

sophisticated forms of jazz. You’ll hear this called “rubato,” but I think<br />

that can be misleading. This Italian word, meaning “robbing” time, can<br />

lead a musician into thinking just stretching out your favorite musical<br />

moments is enough, but of course you’ve got to make up for that time<br />

somewhere else. What does that really mean, though?<br />

Listen to any record of Pablo Casals or Oscar Shumsky playing Bach<br />

- they have the rhythmic solidity of a drummer. The real markers,<br />

the bar lines, are where the pulse is completely stable, but the music<br />

between the bar lines can change all over the place. If you change<br />

anything about rhythm, it’s important to remain grounded and come<br />

back to that groove you worked so hard to develop. The next step that<br />

you can research is what I call “playing over the top of the tempo,” and<br />

it’s something you can easily hear in stride piano playing. A pianist can<br />

have the left hand in time with the right hand stretched out over that.<br />

There’s an even freer way of approaching time I experience all the time<br />

in Wayne Shorter’s band - it’s the essence of breathing together and<br />

feeling our way through the tempo as a group without a strict pulse at<br />

all. We are creating music purely by listening and letting the harmonies<br />

and the sounds guide when to change the music. This is a real sign<br />

of trust, and I think you can only achieve this in groups where you<br />

play together all the time. Wayne’s band has been together for 13 years,<br />

and we can telepathically feel our way through stuff together in a way<br />

that I can’t even explain in words! I think it’s a gift we can’t take credit<br />

for - it’s a spiritual thing. Take a look at an example here.<br />

Even the ability to play without a strict beat is only possible for people<br />

who have an absolute, rock-solid inner pulse. That’s the level you need<br />

to reach to be able to focus deeply on what others are doing around<br />

you while you play. I think everyone should push themselves to<br />

this level.<br />

œ<br />

œ<br />

bœ<br />

j œ œ œ œ bœ<br />

j œ<br />

œ<br />

<br />

Inspiration<br />

I don’t think ignorance is bliss - I think knowledge is always power,<br />

if you have some wisdom to back it up. It’s vital that you learn how<br />

music is put together. I feel as though I’ve established deep relationships<br />

with certain composers to the point where I felt<br />

I understood what they may have been thinking when<br />

they wrote the music. I’ve also felt deep emotional<br />

reactions to music, to the point where at times I feel I<br />

can see cinematic imagery in the music. This is true of<br />

composers like Ravel and especially Bach, which for me<br />

is so meditative and prayer-like. Wayne Shorter talks constantly about<br />

imagery in music!<br />

I like getting students on the piano just to practice voicings, and to<br />

revel in the sound of the piano. It’s not about practicing scales and<br />

arpeggios, or putting restrictions on the music someone needs to<br />

learn. Show a musician some sounds and harmonies, let them put<br />

notes together and experiment - this can really open one’s eyes. Coltrane<br />

said he used to sit at the piano for hours just playing sounds<br />

and chords to inspire him. I’ve always thought, “If that was good<br />

enough for Trane, it’s what I’ll do!” I’ve spent a lot of time hearing<br />

harmonies and responding to them on a personal level. It’s vital to<br />

get to that area where music can paint pictures and take people to a<br />

magical, other world.<br />

I started out as a kid playing by ear, not reading any music. I’m so<br />

grateful I had a teacher who made me learn music. I was so lucky for<br />

that, because I suddenly had access to hundreds of years of music<br />

I could look at and learn from. I was lucky in my childhood to be<br />

exposed to a lot of different music, from pop and R&B to Latin and<br />

world music. Having a wide range of influences gives you a world<br />

of inspiration, and allows you to study how music is put together<br />

throughout the world. All these different cultures have musical<br />

structures that are fascinating. A lot of things I learned about music<br />

were by intuition and from my ears early on. As I got deeply into jazz,<br />

I had to train my ear to hear and respond to music that changes by<br />

the millisecond, and that’s where musicianship comes in. In Wayne<br />

Shorter’s band, there’s so much spontaneity and composition that goes<br />

on the top of the pieces we’re playing! You have to be able to operate<br />

within a harmonically complicated world, but have it sound intuitive<br />

and visceral rather than cerebral.<br />

A vital element to musicianship is singing - I grew up in a house where<br />

we all sang. Early on, I studied with Charles Siani, Principal Bass of<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST 15

7th Annual Wabass Institute - the world's only fullscholarship<br />

double bass camp<br />

June 15-21, 2014<br />

Wabash, IN at the Charley Creek Foundation<br />

www.wabass.com for more information<br />

Eric Larson<br />

Houston Symphony<br />

Hal Robinson<br />

Philadelphia Orchestra<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Time for Three<br />

4th Wabass Workshop - Summerfest at the Curtis<br />

Institute of Music<br />

June 22-25, 2014<br />

www.wabass.com for more information<br />

John Patitucci<br />

Jeffrey Turner<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Joseph Conyers<br />

Grammy Award Winning<br />

Jazz <strong>Bassist</strong><br />

Principal Bass, Pittsburgh<br />

Symphony Orchestra<br />

Time for Three<br />

Assistant Principal Bass,<br />

Philadelphia Orchestra<br />

16 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST

the San Francisco Opera, and he had incredible insights into singing.<br />

I remember playing Marcello sonatas and the first Bach Cello Suite for<br />

him, and he would make me sing to find the music. I’m Italian, I’m a<br />

tenor and I was lucky to be born with some innate ability for this but<br />

this aspect of phrasing is so important.<br />

Identify some records that can be a well of inspiration or joy. I think<br />

a lot of musicians have “go to” recordings that they return to when<br />

they’re dry. If you’re a young player, you should be building that list!<br />

Everybody learns differently, but I’ve had a lot of success getting<br />

people excited about the feeling of music by practicing drums with a<br />

record. I recommend a really swinging record like “Taking Off,” Herbie<br />

Hancock’s first solo record, with Billy Higgins playing. (Check out<br />

Driftin’ here) Find a slow enough tempo that you can play along with<br />

the ride cymbal, and that drummer can make you feel like a million<br />

bucks. If you’re not smiling in about 8 bars, maybe you really need<br />

to dig deeper.<br />

Music is a tricky subject and not everyone responds the same way. I’ve<br />

had instances where the main job I thought I had teaching or collaborating<br />

with people was helping them let go of that incredibly tight grip<br />

they had on their emotions. Sometimes we’re so afraid of making a<br />

mistake that we can’t let go and feel the music. At the end of the day, if<br />

you aren’t doing all the things you’re doing to create an image or tell a<br />

story, you’re missing the mark.<br />

I always draw a distinction between a “correct” performance and one<br />

that is deep and meaningful. I’m totally okay with encouraging a student<br />

to make a mistake and take some chances, because great music is<br />

always being made on the edge! If we play a wrong note, or don’t play<br />

everything the way we want to play it, the problem is we judge our<br />

whole existence on that performance. We feel so crushed or destroyed<br />

for making a mistake…it’s only music, man! Music is deep, important,<br />

emotional, and it makes us feel things, but it’s not the way you measure<br />

yourself in this life. If you do that, you’re setting up music as a very<br />

harsh master, and it becomes an idol. If you do that (and I know, because<br />

I’m sometimes a victim of a perfectionistic streak), you’ll simply<br />

never be satisfied.<br />

Presentation<br />

With all the work of creating a beautiful sound, an unstoppable<br />

groove, and all the meaningful storytelling in the world, some people<br />

stumble at the finish line because of nerves and uncertainty. The most<br />

important lesson you can learn if you’re trying to break into music at<br />

a higher level is that nerves don’t disappear with experience. Although<br />

my level of anxiety is different as a soloist in front of an orchestra than<br />

it is playing next to Wayne Shorter, I still have my concerns and you<br />

will too.<br />

I know when I approach a certain type of music, like a Bottesini show<br />

piece, that I’m going to need a period of practicing to get it ready.<br />

Prior to recording a duet with Jeremy McCoy, I practiced the piece for<br />

a whole year! You may find you need the same time to feel comfortable,<br />

or you might find that you just need to walk out on stage and play<br />

something a few times before you can find peace with it. I can say that<br />

I’ve always poured myself 100% into the work I was given, whether<br />

that was my classical studies in college, or my time with Chick Corea,<br />

or the last 13 years in Wayne Shorter’s band. Even with my best and<br />

most focused work, I’ve found that I still have a big place in my heart<br />

for prayer and meditation. It’s not the same as working on scales, but I<br />

know what will settle me and help me find my feet.<br />

Most of the playing we will do in our lives will be in groups with other<br />

people. There’s something absolutely magical to us and to audiences<br />

about the trust and the community of playing in an ensemble. It<br />

makes it easy to play with others and not be nervous, because we build<br />

that muscle our entire careers. Playing alone, playing a solo, or being<br />

featured is another muscle you need to develop conscientiously, just<br />

like you would intonation or tone. Find out whether you need to settle<br />

yourself into the sweet spot, or if you need to kindle a fire to be at your<br />

best, and learn how to do it for yourself.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Everything I’ve said here constitutes a long list of things to learn. You<br />

have to be willing to struggle and learn new things as long as you play<br />

bass. As an adult, I studied for 2 years with Johnny Schaffer from the<br />

New York Philharmonic. I had to go in there and be willing to say<br />

“show me everything, show me the way you do it” and I learned so<br />

much. In fact, I’m stilling learning so much. It never ends!<br />

For my entire life, I’ve been insatiable in my desire to learn more music,<br />

and to learn more about myself. Once you find that same desire,<br />

you will have no trouble improving all the time. Lean on the resources<br />

available to you, seek out new ones, and connect with your fellow<br />

musicians to grow and to help them too. Being a great person is part of<br />

being a great musician.<br />

Finally, get out into the world and try new things. Stay positive when<br />

it feels like you aren’t playing up to your full potential. You have to remind<br />

yourself that it’s sometimes a few bars in a whole night of music<br />

and you can’t go to a dark place over that. Don’t base your self-worth<br />

over the solo in one tune? The world’s not going to stop! Don’t put the<br />

whole weight of the world on the music you’re playing, because the<br />

only way to guarantee nothing magical happens is if you don’t<br />

take chances. ■<br />

There’s no right or wrong way to deal with performing, it’s simply your<br />

job to figure out what will work best for you in a given situation. Learn<br />

what kind of preparation time you need for a recital, or for a gig, and<br />

stick to it. At the end of the journey, you’ll be where you are because<br />

of the work you put it, and it’s ok to appreciate that. Any performance<br />

is just a snapshot of you at that moment, with all the time and effort<br />

you’ve put in.<br />

NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST 17

www.RobertsonViolins.com<br />

Tel 800-284-6546 | 3201 Carlisle Blvd. NE | Albuquerque, NM USA 87110<br />

18 NOV/DEC 2013 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST