Fulton Gas Works Site Development Plan for the - Virginia ...

Fulton Gas Works Site Development Plan for the - Virginia ...

Fulton Gas Works Site Development Plan for the - Virginia ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

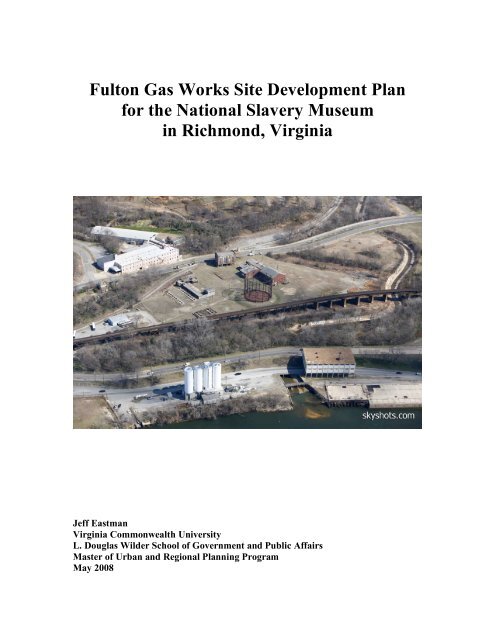

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum<br />

in Richmond, <strong>Virginia</strong><br />

Jeff Eastman<br />

<strong>Virginia</strong> Commonwealth University<br />

L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs<br />

Master of Urban and Regional <strong>Plan</strong>ning Program<br />

May 2008

(page intentionally left blank)

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum<br />

in Richmond, <strong>Virginia</strong><br />

Prepared <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> City of Richmond<br />

Department of Community <strong>Development</strong><br />

Jeff Eastman<br />

<strong>Virginia</strong> Commonwealth University<br />

L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs<br />

Master of Urban and Regional <strong>Plan</strong>ning Program<br />

May 2008

(page intentionally left blank)

Acknowledgements<br />

The <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> could not have been completed in five<br />

months without <strong>the</strong> generous support and insight of <strong>the</strong> following people:<br />

• Reverend Delores McQuinn, City of Richmond Councilwoman to <strong>the</strong> 7 th District<br />

• Jeannie Welliver and Lisbeth Coker in <strong>the</strong> City of Richmond Department of<br />

Economic <strong>Development</strong><br />

• Bob Howard, Deputy Director of <strong>the</strong> City of Richmond Department of Public<br />

Utilities<br />

• Jane Ferrara, Director, City of Richmond Department of Real Estate Services<br />

• David Herring, Interim Director of A.C.O.R.N., <strong>the</strong> Association to Conserve Old<br />

Richmond Neighborhoods<br />

• Tom Stiles, Skyshots Aerial Photography<br />

• Bob Strohm, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Virginia</strong> Historical Society<br />

• Mort Gulak, Brooke Hardin and Ivan Suen, my panel members<br />

Thanks to all of you <strong>for</strong> opening doors <strong>for</strong> me and pointing me in <strong>the</strong> right direction when<br />

I strayed.<br />

My friends and family, especially Meg, also deserve special thanks <strong>for</strong> supporting my<br />

decision to return to school and putting up with my ceaseless talk about urban planning<br />

issues. I owe you all a debt of gratitude.

Contents of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Executive Summary 1<br />

Introduction 3<br />

• Purpose of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 3<br />

• Justification <strong>for</strong> Proposed Use 3<br />

• <strong>Site</strong> Location 5<br />

Part 1. Assessment of Existing Conditions and <strong>Development</strong> Potential 7<br />

1.1 Existing Land Use 7<br />

1.2 <strong>Site</strong> Description 8<br />

1.3 History 9<br />

1.3.1 <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> 10<br />

1.3.2 <strong>Fulton</strong> Neighborhood 12<br />

1.3.3 C&O Tunnel Collapse 14<br />

1.4 Environmental Conditions 15<br />

1.4.1 Floodplain 15<br />

1.4.2 Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area 17<br />

1.4.3 Contamination From Former Use 19<br />

1.4.4 Combined Sewage Overflow From Gillies Creek 21<br />

1.5 Building Conditions 23<br />

1.6 Zoning 30<br />

1.7 Related <strong>Plan</strong>s and Surrounding Influences 32<br />

1.7.1 1960s RRHA <strong>Fulton</strong> Bottom <strong>Plan</strong> 32<br />

1.7.2 City of Richmond Master <strong>Plan</strong> 2000-2020 32<br />

1.7.3 Rocketts Landing 34<br />

1.7.4 City of Richmond Public Marina 35<br />

1.7.5 <strong>Virginia</strong> Capital Trail 36<br />

1.7.6 Market Analysis and Mixed-Use <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 38<br />

1.8 Circulation 39<br />

1.8.1 Traffic Rates 2001-2006 40<br />

1.8.2 Route 5 Relocation 40<br />

1.8.3 Traffic Impact Analyses <strong>for</strong> Route 5 <strong>Development</strong>s 42<br />

1.8.4 GRTC Route and Expansion <strong>Plan</strong>s 43<br />

1.9 Summary of Existing Conditions and <strong>Development</strong> Potential 44<br />

1.9.1 Assets 44<br />

1.9.2 Liabilities 44<br />

Part 2. <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Development</strong> of <strong>the</strong> Study Area 45<br />

2.1 Vision: National Slavery Museum 45<br />

2.2 <strong>Development</strong> Guidelines 46<br />

2.3 Design Guidelines 46<br />

2.4 <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 47<br />

2.5 Implementation 49<br />

Reference List 61<br />

Appendix

List of Tables and Charts<br />

Table 1. <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site Parcel Acreage and Ownership 8<br />

Table 2. Annual Average Daily Traffic <strong>for</strong> Roads Near <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 40<br />

Chart 1. Timeline of Slavery Museum <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> 60<br />

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in <strong>the</strong> City of Richmond 5<br />

Figure 2. Boundaries of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 6<br />

Figure 3. Topography of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> and Surrounding Area 6<br />

Figure 4. Existing Land Use on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 7<br />

Figure 5. <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> Parcel Ownership 8<br />

Figure 6. 1935 Map of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 11<br />

Figure 7. 1905 Sanborn Map of <strong>Fulton</strong> Neighborhood in Relation to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> 13<br />

Figure 8. Parcels Owned by CSX Showing Route to Tunnel Collapse 14<br />

Figure 9. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in <strong>the</strong> 100-Year Floodplain 16<br />

Figure 10. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in <strong>the</strong> 500-Year Floodplain 16<br />

Figure 11. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in a Chesapeake Bay Pres. Area 18<br />

Figure 12. Potentially Contaminated Area of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 20<br />

Figure 13. One of Seven Combined Sewer Overflow Points Into Gillies Creek 21<br />

Figure 14. Location of Combined Sewer Overflows Into Gillies Creek 22<br />

Figure 15. Newton’s Bus Service Building on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 24<br />

Figure 16. <strong>Gas</strong>ometer at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 24<br />

Figure 17. The Top of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong>ometer 25<br />

Figure 18. Building Containing <strong>the</strong> Office, Blacksmith Shop, and Machine Shop 26<br />

Figure 19. Building Containing <strong>the</strong> Office, Blacksmith Shop, and Machine Shop 26<br />

Figure 20. Building Containing <strong>the</strong> Boiler House, Compressor, and Exhauster House 27<br />

Figure 21. Building Containing <strong>the</strong> Boiler House, Compressor, and Exhauster House 27<br />

Figure 22. The Retort House on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 28<br />

Figure 23. The Retort House on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 28<br />

Figure 24. The Steam Generating <strong>Plan</strong>t on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 29<br />

Figure 25. The Steam Generating <strong>Plan</strong>t on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 30<br />

Figure 26. <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> Current Zoning 31<br />

Figure 27. City of Richmond Master <strong>Plan</strong> 2000-2020 Land Use Map 34<br />

Figure 28. Architect’s Rendering of Rocketts Landing Master <strong>Plan</strong> 35<br />

Figure 29. Conceptual Rendering of <strong>the</strong> Proposed City of Richmond Public Marina 36<br />

Figure 30. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in Relation to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> Capital Trail 37<br />

Figure 31. Circulation Around <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> 39<br />

Figure 32. <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in Relation to <strong>the</strong> Proposed Route 5 Relocation 41<br />

Figure 33. Conceptual <strong>Site</strong> Arrangement <strong>for</strong> National Slavery Museum 47<br />

Figure 34. Detailed <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum 48<br />

Figure 35. Rendering of <strong>the</strong> Slavery Museum Building with a Green Roof 54<br />

Figure 36. Open Pier Construction at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> Eye Institute 55<br />

Figure 37. Rendering of <strong>the</strong> Slavery Museum Building with a Stepped Profile 56<br />

Figure 38. The Winfree Cottage 58

Executive Summary<br />

The <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> was prepared as a guide <strong>for</strong> developing <strong>the</strong><br />

site to be <strong>the</strong> home of <strong>the</strong> United States National Slavery Museum.<br />

The <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site is composed of ten separate parcels owned by five entities,<br />

totaling 19.1 acres. The largest parcel is <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong>, an<br />

industrial site that dates to 1856 where coal was converted to gas to light Richmond’s<br />

streets and buildings.<br />

The site is located just sou<strong>the</strong>ast of downtown Richmond, <strong>Virginia</strong>, and sits between <strong>the</strong><br />

long established downtown and <strong>the</strong> exciting new developments occurring along <strong>the</strong><br />

James River. There is a rich history in this area that includes Native American settlement<br />

and <strong>the</strong> founding of <strong>the</strong> City. The area also played an important part in <strong>the</strong> Civil War,<br />

with Chimborazo Hospital located on <strong>the</strong> hill above <strong>the</strong> site and <strong>the</strong> Confederate Naval<br />

Yard along <strong>the</strong> river below. Slaves were brought into and taken out of Richmond by way<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Port of Rocketts, also located along <strong>the</strong> river below <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site.<br />

There are several factors that kept this strategically situated site from being developed<br />

over <strong>the</strong> last several decades. The first is <strong>the</strong> probable contamination from its <strong>for</strong>mer use.<br />

The process of converting coal into gas creates by-products that are environmental<br />

contaminants and are believed to have been disposed of on site. Ano<strong>the</strong>r drawback is that<br />

<strong>the</strong> site is entirely located in <strong>the</strong> 100 and 500-year floodplains due to its proximity to <strong>the</strong><br />

James River and Gillies Creek. For <strong>the</strong>se same reasons, <strong>the</strong> site is located in a<br />

Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area, which also places some restrictions on <strong>the</strong> manner in<br />

which <strong>the</strong> site can be developed. Lastly, Gillies Creek, which <strong>for</strong>ms <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

boundary of <strong>the</strong> study area, is a combined sewer overflow <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> City, which means that<br />

in a heavy rain, raw sewage from homes and businesses may be diverted into <strong>the</strong> creek<br />

and released into <strong>the</strong> James River.<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong>se restrictions, <strong>the</strong>re are many positive aspects that make <strong>the</strong> site appealing <strong>for</strong><br />

development. The <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site is well situated along a highly visible location<br />

on a gateway road into <strong>the</strong> city, and if <strong>the</strong> proposed relocation of Route 5 occurs, along<br />

with <strong>the</strong> large scale developments being constructed fur<strong>the</strong>r south on Route 5, this will<br />

lead to increased traffic and visibility <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> site. Ano<strong>the</strong>r positive in developing <strong>the</strong> site<br />

is that utilities are already present, which will cut down on development time and<br />

expense. Several of <strong>the</strong> existing buildings, though currently in a deteriorated state, are<br />

candidates <strong>for</strong> listing on <strong>the</strong> National Register of Historic Places, which would allow <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> use of tax credits while lending an important historical significance to <strong>the</strong> Slavery<br />

Museum.<br />

Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most important positive is <strong>the</strong> site’s proximity to downtown Richmond, <strong>the</strong><br />

James River, and exciting new developments like Rocketts Landing, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> Capital<br />

Trail, and <strong>the</strong> proposed public marina. Indeed, it is <strong>the</strong> proximity to <strong>the</strong>se developments<br />

as well as <strong>the</strong> rich history of site and surrounding area that led to <strong>the</strong> proposal to use <strong>the</strong><br />

site as <strong>the</strong> home of <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 1

The <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> includes a thorough analysis of existing<br />

conditions such as land use, building conditions, zoning, and circulation, with special<br />

attention paid to <strong>the</strong> history and environmental conditions of <strong>the</strong> site as well as <strong>the</strong> area’s<br />

related plans and surrounding influences.<br />

Building upon <strong>the</strong> site’s assets and minimizing <strong>the</strong> liabilities led to <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mulation of a<br />

number of development and design guidelines, listed below, that will guide <strong>the</strong><br />

preparation and use of <strong>the</strong> site as <strong>the</strong> Slavery Museum.<br />

The following guidelines will dictate how <strong>the</strong> site is developed.<br />

• The ten parcels must be combined under single ownership, and <strong>the</strong> site must be<br />

rezoned “Institutional”.<br />

• The environmental contamination of <strong>the</strong> site will need to be remediated.<br />

• The site will need 200,000 square feet of space <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> museum, and ano<strong>the</strong>r 164,092<br />

square feet <strong>for</strong> parking.<br />

• The site will need vehicular access off Williamsburg Avenue and Peebles Street.<br />

The following guidelines will dictate <strong>the</strong> design of <strong>the</strong> site.<br />

• The Slavery Museum buildings will be prominent on <strong>the</strong> site when viewed from both<br />

Williamsburg Avenue and <strong>the</strong> James River.<br />

• The site shall be developed in a way that minimizes negative impact on <strong>the</strong><br />

environment through pervious paving, green roof technology, bio-retention swales,<br />

and green spaces.<br />

• The new buildings will need to be constructed above <strong>the</strong> level of <strong>the</strong> floodplain to<br />

promote views of <strong>the</strong> river but to heights that respect <strong>the</strong> viewshed of Church Hill<br />

and Chimborazo Hill.<br />

• The site will feature <strong>the</strong> Spirit of Freedom Exhibit Garden and trail along Gillies<br />

Creek.<br />

• The site will be <strong>the</strong> permanent home of <strong>the</strong> Winfree Cottage.<br />

• The gasometer shall hold a slave ship replica and will act as a vista upon entering <strong>the</strong><br />

site.<br />

• The site will connect to <strong>the</strong> public marina, <strong>Virginia</strong> Capital Trail, and <strong>the</strong> Richmond<br />

Slave Trail.<br />

The benefits of having <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum locate in Richmond are<br />

immeasurable. Beyond <strong>the</strong> pure dollars and cents of what <strong>the</strong> museum may bring to <strong>the</strong><br />

City and region, <strong>the</strong> Slavery Museum offers all visitors, whe<strong>the</strong>r Richmonders,<br />

<strong>Virginia</strong>ns, Americans, or <strong>for</strong>eign tourists <strong>the</strong> chance to fully understand this regrettable<br />

though significant portion of our country’s past. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> museum can help heal<br />

<strong>the</strong> divisions that still plague this City nearly a century and a half after slavery was<br />

abolished.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 2

Introduction<br />

Purpose of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

The <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is <strong>the</strong> product of five months of detailed<br />

research, interviews, and brainstorming. More accurately, though, it represents <strong>the</strong><br />

culmination of two years of graduate study in urban planning. Creation of this plan was<br />

<strong>the</strong> primary assignment <strong>for</strong> URSP 762, <strong>Plan</strong>ning Studio II, <strong>the</strong> capstone course in<br />

<strong>Virginia</strong> Commonwealth University’s Master of Urban and Regional <strong>Plan</strong>ning program.<br />

The following members of <strong>the</strong> Studio Panel contributed to <strong>the</strong> development of this plan:<br />

• Dr. I-Shian (Ivan) Suen, Panel Chairperson and Primary Content Advisor<br />

Assistant Professor of Urban Studies and <strong>Plan</strong>ning, L. Douglas Wilder<br />

School of Government and Public Affairs, <strong>Virginia</strong> Commonwealth<br />

University<br />

• Dr. Morton Gulak, Panel Member<br />

Associate Professor of Urban Studies and <strong>Plan</strong>ning, L. Douglas Wilder<br />

School of Government and Public Affairs, <strong>Virginia</strong> Commonwealth<br />

University<br />

• Mr. Brooke Hardin, Panel Member<br />

Deputy Director, City of Richmond Department of Community<br />

<strong>Development</strong><br />

Justification <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> proposed use<br />

Richmond is <strong>for</strong>ever linked to history as a participant in <strong>the</strong> transatlantic and interstate<br />

slave trade. It is critical to <strong>the</strong> understanding of American history to tell <strong>the</strong> story of this<br />

regrettable but none<strong>the</strong>less real era of our past. Richmond’s legacy as <strong>the</strong> slave trade<br />

capital of <strong>the</strong> United States has been a black eye in <strong>the</strong> past, but <strong>the</strong> time is ripe to<br />

confront this issue in a way that can heal <strong>the</strong> still lingering tensions. Just last spring<br />

Richmond unveiled a reconciliation statue that matches ones found in Liverpool, England<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Republic of Benin in Africa, o<strong>the</strong>r participants in <strong>the</strong> transatlantic slave trade.<br />

Liverpool has taken <strong>the</strong> opportunity to confront <strong>the</strong>ir past involvement in <strong>the</strong> slave trade<br />

by becoming <strong>the</strong> home of <strong>the</strong> International Slavery Museum, and Richmond, which<br />

played a primary role in <strong>the</strong> history of slavery in <strong>the</strong> United States, should not let this<br />

opportunity pass <strong>the</strong>m by <strong>for</strong>ever.<br />

The area near and including <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> was actually considered several years<br />

ago <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> location of <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum be<strong>for</strong>e it was eventually awarded to<br />

Fredericksburg, <strong>Virginia</strong> (Redmon and Krishnamurthy, 2001). The site of <strong>the</strong> museum<br />

would have been largely on City owned property close to <strong>the</strong> river, near where <strong>the</strong><br />

Intermediate Terminal building is today, and would have included <strong>the</strong> Lehigh Cement<br />

Company parcel. The mission of <strong>the</strong> museum was to focus on <strong>the</strong> role of slavery from <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 3

time of <strong>the</strong> Nation’s founding in 1776 through <strong>the</strong> Emancipation Proclamation and Civil<br />

War.<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately <strong>for</strong> Richmond, <strong>the</strong> Slavery Museum’s Board of Directors chose to locate<br />

<strong>the</strong> museum in Fredericksburg, on 39 acres of a 2,100 acre development along <strong>the</strong><br />

Rappahannock River called Celebrate <strong>Virginia</strong> that would include a golf course and<br />

commercial areas. According to a 2001 Richmond Times-Dispatch article, <strong>the</strong> developer<br />

of <strong>the</strong> site, Larry Silver, donated <strong>the</strong> land to <strong>the</strong> museum (Redmon and Krishnamurthy).<br />

Councilwoman Delores McQuinn, whose district includes <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site, was<br />

on City Council at <strong>the</strong> time, and says that <strong>the</strong> Council went to great lengths to entice <strong>the</strong><br />

Slavery Museum to locate in Richmond, even without seeing a feasibility study. Council<br />

offered millions of dollars to <strong>the</strong> museum’s board, and even went so far as to set aside<br />

money <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> environmental remediation of <strong>the</strong> site. Councilwoman McQuinn feels now,<br />

as she did <strong>the</strong>n, that Richmond is <strong>the</strong> proper home <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> museum.<br />

Though Richmond City Council made ef<strong>for</strong>ts to secure <strong>the</strong> area around <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> as<br />

<strong>the</strong> site of <strong>the</strong> museum, <strong>the</strong>n City Councilman Sa’ad El-Amin had concerns that <strong>the</strong>re was<br />

nothing else in <strong>the</strong> immediate area to keep museum visitors down <strong>the</strong>re. That was true<br />

<strong>the</strong>n, but in <strong>the</strong> years since <strong>the</strong> original proposal, <strong>the</strong>re have been many positive<br />

developments in this area, including Rocketts Landing, which will bring both residential<br />

and commercial activity to this area of <strong>the</strong> City. At <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site, <strong>the</strong> Slavery<br />

Museum can connect to <strong>the</strong> City’s Slave Trail, adding a wealth of in<strong>for</strong>mation to <strong>the</strong><br />

moving experience of <strong>the</strong> trail. When combined with <strong>the</strong> City’s plans <strong>for</strong> a public marina<br />

and <strong>the</strong> completion of <strong>the</strong> Capital Trail, this area will be one of <strong>the</strong> City’s centers of<br />

recreation, and hopefully, tourism as well.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> location of <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum was awarded to Fredericksburg,<br />

ground has yet to be broken, and recent newspaper articles report that slow fundraising<br />

results may fur<strong>the</strong>r hinder plans to begin construction. The time is right <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> museum<br />

to reassess <strong>the</strong>ir choice of location and consider a site that more closely ties <strong>the</strong> mission<br />

of <strong>the</strong> museum to its location. The powerful story that <strong>the</strong> museum will tell fits better in<br />

Richmond than it does in <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> woods outside of Fredericksburg.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 4

<strong>Site</strong> Location<br />

The study area consists of a group of parcels surrounding <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

located just sou<strong>the</strong>ast of downtown Richmond, <strong>Virginia</strong> (see Figure 1). The site is<br />

bounded by Gillies Creek on <strong>the</strong> south, Williamsburg Avenue on <strong>the</strong> east, and Main<br />

Street on <strong>the</strong> west (see Figure 2), and bisected by <strong>the</strong> raised railroad trestles of <strong>the</strong> CSX<br />

Transportation Company. Although <strong>the</strong>re are ten parcels that make up <strong>the</strong> study area, <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> purposes of this paper, <strong>the</strong> area will be referred to as <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site.<br />

Figure 1. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in <strong>the</strong> City of Richmond<br />

The <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site and surrounding area are a geographic low point (see Figure 3),<br />

sitting at <strong>the</strong> bottom of Church, Chimborazo, and <strong>Fulton</strong> Hills, with <strong>the</strong> James River on<br />

<strong>the</strong> fourth side. These hills are home to <strong>the</strong> first neighborhoods of Richmond and are rich<br />

in history, architecture, and character. Downtown Richmond, including <strong>the</strong> State Capitol<br />

building, financial district, Shockoe Slip and Shockoe Bottom, is just over a mile away to<br />

<strong>the</strong> northwest. The Tobacco Row apartment buildings (old tobacco warehouses converted<br />

into hundreds of apartments in <strong>the</strong> last two decades) are located less than a mile away,<br />

and Shockoe Bottom is <strong>the</strong> City’s main entertainment destination.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 5

Figure 2. Boundaries of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong><br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

Figure 3. Topography of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> and Surrounding Area<br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 6

Part 1. Assessment of Existing Conditions and<br />

<strong>Development</strong> Potential<br />

1.1 Existing Land Use<br />

All of <strong>the</strong> land in <strong>the</strong> study area is vacant at <strong>the</strong> present time (see Figure 4), with <strong>the</strong><br />

exception of a parcel that is operated as a bus repair facility. Existing land use in <strong>the</strong> area<br />

surrounding <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site is presently mixed. Just north of <strong>the</strong> study area along<br />

Williamsburg Avenue sits a house that, according to City tax records, was built in 1780.<br />

The larger area of yellow in Figure 4 shows <strong>the</strong> residential neighborhood of Church Hill.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>re used to be a thriving neighborhood in <strong>the</strong> area around <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong><br />

<strong>Works</strong>, <strong>the</strong> site is now mostly surrounded by small industrial operations and vacant land.<br />

However, due to its proximity to downtown and <strong>the</strong> river, this area is garnering increased<br />

interest from <strong>the</strong> development community. Much of that interest is driven by <strong>the</strong> Rocketts<br />

Landing development, which, when coupled with <strong>the</strong> plans <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> public marina and<br />

<strong>Virginia</strong> Capital Trail, could make this a very attractive place to live, work, and play.<br />

Figure 4. Existing Land Use on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong><br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 7

1.2 <strong>Site</strong> Description<br />

Ten separate parcels comprise <strong>the</strong> study area, totaling 19.1 acres (see Figure 5 and Table<br />

1). The largest parcel, at 10.4 acres, is <strong>the</strong> physical site of <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong>, owned<br />

by <strong>the</strong> City’s Department of Public Utilities (DPU). The next largest parcel is <strong>the</strong> 3.3 acre<br />

piece of land between <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> and Gillies Creek that is owned by RRHA, <strong>the</strong><br />

Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority. The o<strong>the</strong>r eight parcels are all small,<br />

with no one parcel larger than 1.3 acres. Owners of <strong>the</strong>se parcels include <strong>the</strong> CSX<br />

Transportation Company, <strong>the</strong> City’s Department of Parks and Recreation, and one parcel<br />

owned by Newton’s Bus Service.<br />

Figure 5. <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> Parcel Ownership<br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

Table 1. <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site Parcel Acreage and Ownership<br />

Parcel # Acreage Owner Name<br />

1 10.4 City Of Richmond Department of Public Utilities<br />

2 3.3 Richmond Redevelopment & Housing Authority<br />

3 1.3 City Of Richmond Department of Parks & Recreation<br />

4 1.2 Richmond Redevelopment & Housing Authority<br />

5 1.1 Newton’s Bus Service<br />

6 0.7 C S X Transportation<br />

7 0.4 C S X Transportation<br />

8 0.4 C S X Transportation<br />

9 0.2 C S X Transportation<br />

10 0.2 City Of Richmond Department of Parks & Recreation<br />

19.1<br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 8

1.3 History<br />

There is a long history of human settlement in this area of <strong>the</strong> City. Indeed, this site and<br />

<strong>the</strong> surrounding area have played a prominent role in <strong>the</strong> history and development of<br />

Richmond. In his 1976 book Richmond, <strong>the</strong> Story of a City, author Virginius Dabney tells<br />

us that <strong>the</strong> valley between <strong>the</strong> hills and <strong>the</strong> river in this area (on both sides of Gillies<br />

Creek) was farmed by a group of Powhatan Indians under <strong>the</strong> leadership of Little<br />

Powhatan, son of Chief Powhatan. Gabriel Archer, <strong>the</strong> chronicler of an expedition of<br />

English explorers who traveled up <strong>the</strong> James River in 1607 with Christopher Newport,<br />

wrote of a “playne between <strong>the</strong> hill and river, whereon he [Little Powhatan] soes his<br />

wheate, beane, peaze, tobacco, pompions, gourdes, Hempe, flaxe, etc.” (Dabney, 1976).<br />

The study area, like <strong>the</strong> hill that stands to <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast, is named <strong>for</strong> James Alexander<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong>, who built his home in 1800 where Powhatan Village once stood (Dabney, 1976).<br />

This area was key in <strong>the</strong> early development of Richmond because it marked <strong>the</strong> last<br />

navigable stretch of <strong>the</strong> James River be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> fall line. The area along <strong>the</strong> James River<br />

just below <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site was known as <strong>the</strong> Port of Rocketts, where, in <strong>the</strong> 1700s,<br />

goods from <strong>the</strong> interior of <strong>Virginia</strong> were loaded on ocean-going ships, and vice versa.<br />

Later, this area was used to load ano<strong>the</strong>r export, slaves, onto ships <strong>for</strong> transport fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

south. This area was also home to <strong>the</strong> Confederate Naval Shipyard, which is today<br />

commemorated by a stone marker at <strong>the</strong> corner of Main Street and Peebles Street.<br />

Church Hill and Chimborazo Hill, located north and east of <strong>the</strong> study area, respectively,<br />

are both City Old and Historic Districts and have each played important roles in <strong>the</strong><br />

history of Richmond. From a vantage point on Church Hill, near <strong>the</strong> present day<br />

Confederate Sailors and Soldiers Monument in Libby Park, William Byrd II surveyed <strong>the</strong><br />

bend of <strong>the</strong> James River and found it remarkably similar to <strong>the</strong> view from Richmondupon-Thames<br />

in England, and this is how <strong>the</strong> City got its name. Church Hill encompasses<br />

<strong>the</strong> original development of <strong>the</strong> City of Richmond, and is so named <strong>for</strong> St. Johns Church,<br />

where Patrick Henry proclaimed “Give me Liberty or Give me Death” (Kimmel, 1958).<br />

Chimborazo Hill, located adjacent to Church Hill to <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast, was home to one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> largest Confederate hospitals during <strong>the</strong> Civil War. All structures dating from that<br />

period have vanished, but <strong>the</strong> site is now a museum operated by <strong>the</strong> National Park<br />

Service as part of <strong>the</strong> Richmond National Battlefield Parks and features interpretive<br />

displays on medical treatment during <strong>the</strong> war.<br />

Shortly after <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> Civil War, President Lincoln and his son Tad traveled by boat<br />

to Richmond to view <strong>the</strong> damage firsthand. They disembarked at <strong>the</strong> Port of Rocketts and<br />

walked through <strong>the</strong> city to <strong>the</strong> Confederate White House. An April 4 th , 1865 article in <strong>the</strong><br />

New York Times reports that Lincoln was guided through <strong>the</strong> city by many of <strong>the</strong> slaves<br />

his Emancipation Proclamation had freed: “The arrival of <strong>the</strong> President soon got noised<br />

abroad, and <strong>the</strong> colored population turned out in great <strong>for</strong>ce, and <strong>for</strong> a time blockaded <strong>the</strong><br />

quarters of <strong>the</strong> President, cheering vociferously. It was to be expected, that a population<br />

that three days since were in slavery, should evince a strong desire to look upon <strong>the</strong> man<br />

whose edict had struck <strong>for</strong>ever <strong>the</strong> manacles from <strong>the</strong>ir limbs”. It is <strong>the</strong> area’s history that<br />

makes it such an appropriate site <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Slavery Museum.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 9

1.3.1 <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

Richmond was one of <strong>the</strong> first cities in <strong>the</strong> United States to use gas as a source of light<br />

and heat. Even in those days, streetlights were used in order to decrease crime. On<br />

November 29, 1849, <strong>the</strong> City adopted an ordinance that created a “Committee on Light”<br />

which was tasked “to have constructed suitable works <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> manufacture and<br />

distribution of carbureted hydrogen gas from bituminous coal <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> purpose of<br />

illumination through <strong>the</strong> streets, lanes, and alleys of <strong>the</strong> city” (City of Richmond DPU,<br />

1935).<br />

The Committee on Light purchased two lots on Cary Street between Fifteenth and<br />

Sixteenth streets as <strong>the</strong> site of <strong>the</strong> gas works, and construction began soon <strong>the</strong>reafter.<br />

The gas works began operations in 1851, and use of gas caught on quickly, as <strong>the</strong> number<br />

of private users grew to 627 in <strong>the</strong> first year, and <strong>the</strong>n 937 in <strong>the</strong> next year a 49% increase<br />

(City of Richmond DPU, 1935). At this point <strong>the</strong> gas was being used <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> purposes of<br />

lighting interior spaces and streets. City officials soon realized that <strong>the</strong> plant <strong>the</strong>y had<br />

built just two years prior would soon have to be enlarged to meet <strong>the</strong> growing demand,<br />

but un<strong>for</strong>tunately, <strong>the</strong> current site was not suitable <strong>for</strong> expansion. Thus, <strong>the</strong> Committee on<br />

Light recommended <strong>the</strong> purchase of new land near Rocketts Landing at <strong>the</strong> current site of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong>. The 1935 annual report of <strong>the</strong> Department of Public Utilities (in 1919 <strong>the</strong><br />

Committee on Light became a division of <strong>the</strong> Department of Public Utilities) posits “It<br />

seems possible that <strong>the</strong> extremely offensive odors which were produced by <strong>the</strong> purifying<br />

process <strong>the</strong>n in use had something to do with this recommendation”. The current <strong>Gas</strong><br />

<strong>Works</strong> site was purchased in 1853, and construction began immediately (see Figure 6).<br />

The new plant took over gas production <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> city on October 5, 1856.<br />

The gas business continued to grow in <strong>the</strong> years following construction of <strong>the</strong> new <strong>Gas</strong><br />

<strong>Works</strong>, but as <strong>the</strong> Civil War loomed, improvements were delayed, and <strong>the</strong> work<strong>for</strong>ce was<br />

trimmed in order to free men up to fight <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Confederacy. To free up even more<br />

soldiers, it was suggested that “negroes be substituted <strong>for</strong> present employees”, and so it<br />

was that in 1862 <strong>the</strong> Committee on Light presented a resolution to City Council “to<br />

purchase as many negroes as in <strong>the</strong> opinion of <strong>the</strong> Chairman of <strong>the</strong> Committee and <strong>the</strong><br />

Superintendent of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> may be advisable to secure labour <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> gas works”<br />

(City of Richmond DPU, 1935). City Council approved <strong>the</strong> resolution and gave <strong>the</strong><br />

Committee $30,000 to buy slaves to work in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong>. The same buildings that<br />

<strong>the</strong>se slaves worked in may house <strong>the</strong> National Slavery Museum.<br />

The fire set by retreating Confederate soldiers in Richmond on April 3, 1865 that<br />

destroyed so much of <strong>the</strong> city caused a complete shutdown of <strong>the</strong> gas system, but workers<br />

were asked to restore <strong>the</strong> works to service be<strong>for</strong>e long in order to improve security and<br />

also to facilitate nighttime reconstruction.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 10

Figure 6. 1935 Map of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong><br />

source: City of Richmond Department of Public Utilities<br />

In <strong>the</strong> years after <strong>the</strong> Civil War, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> continued to expand and add new<br />

services, all while surviving numerous floods that caused temporary setbacks. In <strong>the</strong> late<br />

19 th century, as electric light use became more widespread, use of gas was shifted from<br />

lighting to cooking and heating. The 1930 Annual Report from <strong>the</strong> Department of Public<br />

Utilities relates that <strong>the</strong> Nolde Bro<strong>the</strong>rs bakery installed a 73 foot traveling bake oven that<br />

could bake 4,000 pounds of bread per hour, using up to 4,000 cubic feet of gas an hour.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r large gas consumers include one who used gas in <strong>the</strong>ir meat-smoking operation,<br />

and ano<strong>the</strong>r who used gas-fired kettles to make soap. (City of Richmond DPU, 1930).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> early 1950s, <strong>the</strong> Department of Public Utilities began to convert <strong>the</strong> system from<br />

manufactured gas to natural gas, and this began <strong>the</strong> slow decline <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site.<br />

Natural gas burned hotter and more efficiently than manufactured gas did. Large concrete<br />

cradles were constructed on <strong>the</strong> gas works site to hold giant propane tanks. Natural gas<br />

was now being pumped into Richmond via pipeline from Greene County, and <strong>the</strong> gas<br />

works served only as a “peak use” source, mixing propane with air to lower <strong>the</strong><br />

combustion efficiency down to <strong>the</strong> level of natural gas. This system worked fine until<br />

1972, when <strong>the</strong> flood from Hurricane Agnes dislodged <strong>the</strong> propane tanks from <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

cradles. Miraculously, none of <strong>the</strong> propane tanks floated away or exploded, but due to<br />

this problem <strong>the</strong> tanks were moved to less flood prone areas on <strong>the</strong> south side of <strong>the</strong> river,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> active use of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site ended.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 11

1.3.2 <strong>Fulton</strong> Neighborhood<br />

During <strong>the</strong> same time that <strong>the</strong> city was buying <strong>the</strong> property to house <strong>the</strong> expanded <strong>Gas</strong><br />

<strong>Works</strong>, homes were being built to <strong>the</strong> south of <strong>the</strong> site. In his 2007 book Built by Blacks:<br />

African American Architecture & Neighborhoods in Richmond, VA, local preservationist<br />

Seldon Richardson explains that “lots were <strong>for</strong> sale in what was known as <strong>the</strong> town of<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> as early as 1853”.<br />

The <strong>Fulton</strong> neighborhood that emerged in <strong>the</strong> 1850s was originally a white neighborhood,<br />

but when <strong>the</strong> white families moved out in <strong>the</strong> late 1800s, <strong>the</strong> area became populated by<br />

<strong>for</strong>mer slaves and <strong>the</strong>ir families (Bass, 2007). These <strong>for</strong>mer slaves prospered in <strong>the</strong>ir new<br />

neighborhood, and established deep roots around churches and schools. <strong>Fulton</strong> was like<br />

many of today’s prized urban neighborhoods, built on <strong>the</strong> street grid with community<br />

commercial centers (see Figure 7). The <strong>Fulton</strong> neighborhood was <strong>the</strong> eastern stop on <strong>the</strong><br />

City’s trolley line, and it naturally became <strong>the</strong> place where people coming in from <strong>the</strong><br />

country would park to ride <strong>the</strong> trolley into downtown. The supermarkets, furniture stores,<br />

and movie <strong>the</strong>aters in <strong>Fulton</strong> served <strong>the</strong>se early commuters as well as <strong>the</strong> rural<br />

community in eastern Henrico County.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> trolley stopped running and commuters chose to drive into <strong>the</strong> city <strong>the</strong>mselves,<br />

<strong>the</strong> prosperity that had blessed <strong>Fulton</strong> declined. The rise of suburbs pulled more money<br />

out of <strong>the</strong> neighborhood that was by now a firmly established African American<br />

community, and <strong>the</strong> decline continued into <strong>the</strong> mid-20 th century. In <strong>the</strong> mid 1960s, City<br />

Council commissioned <strong>the</strong> Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) to<br />

complete a study to see what could be done about <strong>the</strong> deteriorating situation in <strong>Fulton</strong>.<br />

After much debate between <strong>the</strong> residents of <strong>Fulton</strong>, City officials, and <strong>the</strong> RRHA, <strong>Fulton</strong>,<br />

like so many inner-city neighborhoods across <strong>the</strong> country during <strong>the</strong> urban renewal<br />

fervor, fell victim to <strong>the</strong> bulldozer. The last structure remaining in <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer bustling<br />

neighborhood fell in <strong>the</strong> early 1980s. With <strong>the</strong> exception of a suburban residential<br />

development, a city park, and a few industrial buildings, nothing has materialized where<br />

<strong>the</strong> neighborhood once stood. That this neighborhood became <strong>the</strong> home of freed slaves<br />

lends more credence to <strong>the</strong> historical significance of <strong>the</strong> area as <strong>the</strong> site of <strong>the</strong> Slavery<br />

Museum.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 12

Figure 7. 1905 Sanborn Map of <strong>Fulton</strong> Neighborhood in Relation to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

source: VCU Libraries Digital Archive of Sanborn Maps<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 13

1.3.3 C&O Tunnel Collapse<br />

Two slender parcels in <strong>the</strong> study area running north-south (see Figure 8) are currently<br />

owned by <strong>the</strong> CSX Transportation Company and are a grim reminder of a tunnel collapse<br />

that occurred in Richmond in 1925. The tunnel, built in 1873 by <strong>the</strong> Chesapeake and<br />

Ohio (C&O) Railway Company (CSX absorbed C&O in 1987), ran underneath Church<br />

Hill just to <strong>the</strong> north of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong>, and continued underneath Jefferson Park. By<br />

1925 <strong>the</strong> tunnel needed to be widened to accommodate larger trains. On October 2, 1925,<br />

during <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> widening, a 100 to 200 foot stretch of <strong>the</strong> tunnel under Jefferson<br />

Park collapsed. Three men were killed that day, and <strong>the</strong> tunnel was later filled with sand<br />

and sealed at both ends. The tracks leading into <strong>the</strong> tunnel were later removed, yet CSX<br />

still retains ownership of <strong>the</strong> land.<br />

Figure 8. Parcels Owned by CSX Showing Route to Tunnel Collapse<br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 14

1.4 Environmental Conditions<br />

1.4.1 Floodplain<br />

In <strong>the</strong> past 100 years, floods have caused more loss of life and property damage in <strong>the</strong><br />

Unites States than any o<strong>the</strong>r type of natural disaster (Daniels and Daniels, 2003).<br />

Richmond has not been immune to flooding, and <strong>the</strong> entire <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> study area<br />

is located in <strong>the</strong> 100 and 500-year floodplains due to its proximity to <strong>the</strong> James River and<br />

Gillies Creek (see Figures 9 and 10). As such, any development that occurs on this site<br />

must be in compliance with City of Richmond Municipal Code Chapter 50, Article II<br />

[Floodplain Management]. The delineation of floodplain districts has been prepared <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> City by <strong>the</strong> Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and was most recently<br />

updated in July of 1998. The boundaries of <strong>the</strong> floodplain districts have been established<br />

on flood insurance rate maps, or FIRMS, also prepared by FEMA.<br />

There are three types of floodplain districts: floodway districts, flood fringe districts, and<br />

approximate floodplain districts. Floodway districts are those where <strong>the</strong> deepest and most<br />

frequent flood flows are conducted, while flood fringe districts are those that would be<br />

lightly inundated by a 100-year flood.<br />

Generally, development of <strong>the</strong> land in a floodplain requires a building permit and/or a<br />

land disturbing activity permit, and <strong>the</strong> development would have to be in strict<br />

compliance with <strong>the</strong> applicable sections of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> Uni<strong>for</strong>m Statewide Building<br />

Code. The development could not adversely affect <strong>the</strong> capacity of <strong>the</strong> floodway or<br />

watercourse. If any alteration or relocation of <strong>the</strong> waterway were to occur, approval<br />

would need to be obtained from <strong>the</strong> U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Additionally, no new<br />

residential construction will be allowed without provision of adequate vehicular access to<br />

<strong>the</strong> site prior to and during a 100-year flood.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 15

Figure 9. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in <strong>the</strong> 100-Year Floodplain<br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

Figure 10. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in <strong>the</strong> 500-Year Floodplain<br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 16

1.4.2 Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area<br />

The <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site is also located in a Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area, with <strong>the</strong> main<br />

portion in a Resource Management Area, and <strong>the</strong> land along Gillies Creek in a Resource<br />

Protection Area (see Figure 11). As such, any development that occurs on <strong>the</strong> study site<br />

must also abide by <strong>the</strong> regulations set <strong>for</strong>th in City of Richmond Municipal Code,<br />

Chapter 50, Article IV [Chesapeake Bay Preservation Areas]. The Chesapeake Bay<br />

Preservation Act was adopted by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> General Assembly in 1988, and is one<br />

portion of a multi-state initiative to confront issues of environmental degradation of <strong>the</strong><br />

Chesapeake Bay and its watershed.<br />

The Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act was designed to protect and improve <strong>the</strong> water<br />

quality of <strong>the</strong> Bay and its watershed by minimizing <strong>the</strong> effects of human activity on <strong>the</strong><br />

land and tributaries that feed <strong>the</strong> Bay. The Act divides preservation areas into two<br />

designations: resource protection areas and resource management areas. The Act also<br />

allows <strong>the</strong> identification of intensely developed areas suitable <strong>for</strong> redevelopment.<br />

Intensely developed areas are those where heavy development has occurred and little of<br />

<strong>the</strong> natural environment remains.<br />

Resource protection areas are those that are adjacent to water bodies that have a perennial<br />

flow and intrinsic water quality due to <strong>the</strong> natural processes <strong>the</strong>y per<strong>for</strong>m. These areas<br />

<strong>for</strong>m a buffer of not less than 100 feet along both sides of a designated water body.<br />

Resource protection areas also include those that are sensitive to impacts that may cause<br />

significant degradation to <strong>the</strong> quality of state waters. The Act recognizes that <strong>the</strong>se lands<br />

are important to <strong>the</strong> removal or reduction of sediments, nutrients, and potentially toxic<br />

substances in runoff. Resource protection areas include tidal wetlands and tidal shores,<br />

among o<strong>the</strong>r designations.<br />

Resource management areas include land that could have a detrimental effect on water<br />

quality or <strong>the</strong> functionality of resource protection areas if improperly used or developed.<br />

Resource management areas also include land contiguous to <strong>the</strong> inland boundary of<br />

designated protection areas. These areas can take <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m of floodplains, highly erodible<br />

soils including steep slopes, highly permeable soils, and non-tidal wetlands, among o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

designations.<br />

The Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act requires that certain per<strong>for</strong>mance criteria be met,<br />

including: disturbing as little land as possible <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> proposed development; preserving<br />

and/or providing indigenous vegetation to enhance retention of non-point source<br />

pollution and prevent runoff; minimize <strong>the</strong> amount of impervious cover on <strong>the</strong> proposed<br />

development; and contain a comprehensive stormwater management plan in compliance<br />

with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Virginia</strong> Stormwater Management Regulations.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 17

Figure 11. Location of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong> in a Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area<br />

source: City of Richmond GIS<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 18

1.4.3 Contamination From Former Use<br />

At <strong>the</strong> present time, <strong>the</strong> extent of environmental contamination on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

site from its <strong>for</strong>mer use is unknown. Scientific studies of <strong>the</strong> soil have not been<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med on this site, but manufactured gas sites were common around <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States, and remediation of o<strong>the</strong>r such sites around <strong>the</strong> country can shed light on <strong>the</strong> types<br />

of contamination that are likely to be present.<br />

The <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> was a coal gasification plant, meaning that coal was converted<br />

into gas <strong>for</strong> later use. For about a hundred years, from <strong>the</strong> 1850s to <strong>the</strong> 1950s,<br />

manufactured gas was <strong>the</strong> primary source of energy <strong>for</strong> lighting and heating (Fischer,<br />

1999). At <strong>the</strong> peak of <strong>the</strong> industry, <strong>the</strong>re were an estimated 10,000 manufactured gas<br />

plants (MGP) across North America and Europe. In o<strong>the</strong>r locations, like in Richmond, <strong>the</strong><br />

availability of less expensive alternatives like natural gas and electricity led to <strong>the</strong> demise<br />

of <strong>the</strong> manufactured gas plant. Many of <strong>the</strong> MGP sites were used <strong>for</strong> delivery of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

new types of energy, though o<strong>the</strong>rs were dismantled and repurposed without<br />

consideration of <strong>the</strong> environmental impacts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer use. Some estimates show that<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are as many as 2,500 <strong>for</strong>mer MGP sites in <strong>the</strong> United States, and <strong>the</strong> cost of<br />

remediation could run between $25-75 billion (Fischer, 1999).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> coal gasification process, <strong>the</strong> distillation of bituminous coal in oxygen deficient<br />

containers called retorts produces gas. One of <strong>the</strong> by-products of <strong>the</strong> process is coke, a<br />

solid fuel that can be used <strong>for</strong> heating. The gases produced during <strong>the</strong> coal burning are<br />

condensed, removing tar, ano<strong>the</strong>r by-product. The gas is <strong>the</strong>n treated to remove ammonia<br />

and gaseous sulfur compounds, and after this stage it is sent through <strong>the</strong> station meter <strong>for</strong><br />

measuring. The gas finally ended up in a large storage tank called a gasometer, where it<br />

would eventually be sent through gas mains <strong>for</strong> consumption by customers.<br />

It was not uncommon at MGP sites <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> waste products from <strong>the</strong> manufacturing<br />

process to be disposed of on site by burial. The specific inputs and processing techniques<br />

used to create <strong>the</strong> gas dictate <strong>the</strong> volume, toxicity, and chemical composition of <strong>the</strong><br />

contamination. A 1999 study by scientists at <strong>the</strong> Georgia Institute of Technology reports<br />

that, generally, <strong>the</strong> waste products at MGP sites include: tars; oils; inorganic spent oxides<br />

(ferrocyanide); benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX); volatile organic<br />

compounds (VOCs); semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs); phenolics; polynuclear<br />

aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); cyanides; thiocynates; metals (Arsenic, copper, lead,<br />

nickel, and zinc); ammoniates; nitrates; sludges; ash; ammonia; lime wastes; and<br />

sulfates/sulfides. Coal tars are a particular problem, as <strong>the</strong>y migrate down through <strong>the</strong> soil<br />

and often pool up in <strong>the</strong> bottom of aquifers, becoming a continual source of<br />

contamination.<br />

In 1987, under contract with <strong>the</strong> Environmental Protection Agency, scientists from <strong>the</strong><br />

Research Triangle Institute investigated six manufactured gas sites on <strong>the</strong> east coast of<br />

<strong>the</strong> U.S., and one of <strong>the</strong> sites <strong>the</strong>y visited was <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong>. During <strong>the</strong>ir visit,<br />

<strong>the</strong> scientists met with DPU employees, toured <strong>the</strong> site and its structures, and examined<br />

<strong>the</strong> site perimeter <strong>for</strong> wastes and dumping locations. As a result of <strong>the</strong>ir investigations,<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 19

<strong>the</strong> group concluded that “<strong>the</strong> area between <strong>the</strong> gas plant and <strong>the</strong> creek (see Figure 12)<br />

shows substantial signs of being a dump area <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> plant, with contaminated woodchips,<br />

ash, coke, firebricks, and tar present” (Harkins et. al., 1987).<br />

A 2005 summary of hindrances to development in this area by <strong>the</strong> City of Richmond<br />

Department of Economic <strong>Development</strong> noted that environmental contamination is<br />

probably not limited to just <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> parcel. According to this summary, old<br />

documents indicate that <strong>the</strong>re are waste trenches containing coal tars in <strong>the</strong> RRHA parcel<br />

north of Gillies Creek. In addition, <strong>the</strong> paper notes that creosote is likely present along<br />

<strong>the</strong> abandoned CSX railroad right-of-way.<br />

It is clear that thorough testing must be completed to gain a comprehensive understanding<br />

of <strong>the</strong> contamination at <strong>the</strong> site. Testing can be done any number of ways, and should<br />

include soil screening, soil sampling, and groundwater sampling. Remediation can take<br />

many <strong>for</strong>ms, but will likely entail removal of contaminated soil <strong>for</strong> off-site treatment and<br />

replacement with uncontaminated soil.<br />

Figure 12. Potentially Contaminated Area of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong><br />

source: courtesy Skyshots Aerial Photography<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 20

1.4.4 Combined Sewage Overflow From Gillies Creek<br />

Gillies Creek, which has been made into a concrete channel, serves as <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn border<br />

of <strong>the</strong> study area, and contains a combined sewer overflow (see Figure 13). According to<br />

<strong>the</strong> City of Richmond Department of Public Utilities website, a combined sewer overflow<br />

(CSO) is “a discharge of untreated storm and wastewater from a combined sewer into <strong>the</strong><br />

environment” (2008). Current engineering standards are to construct separate systems <strong>for</strong><br />

sewage and storm water, and in Richmond, no CSO’s have been built since <strong>the</strong> early<br />

1950s. Under normal conditions, a combined sewer moves wastewater from homes and<br />

businesses along with water from street drains to <strong>the</strong> wastewater treatment plant on <strong>the</strong><br />

south side of <strong>the</strong> James River. However, during a period of heavy or extended rain in<br />

which <strong>the</strong> flow exceeds what <strong>the</strong> combined sewer can handle, excess flow is discharged<br />

into <strong>the</strong> James River by way of Gillies Creek.<br />

There are seven points along Gillies Creek where combined sewer overflow is discharged<br />

into <strong>the</strong> creek (see area highlighted in yellow on Figure 14). This discharge keeps<br />

sewerage from backing up into people’s homes, but in order to do that it releases<br />

untreated human and industrial waste, toxic materials, and debris into Gillies Creek, and<br />

eventually <strong>the</strong> James River, exposing people and downstream ecosystems to potentially<br />

hazardous bacteria and microorganisms. This not only pollutes <strong>the</strong> river, but it makes<br />

developing <strong>the</strong> land surrounding Gillies Creek a less attractive proposition.<br />

Figure 13. One of Seven Combined Sewer Overflow Points Into Gillies Creek<br />

source: photograph by <strong>the</strong> author<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 21

In 1988 <strong>the</strong> City completed a study of <strong>the</strong> CSO program to see what improvements could<br />

be made. The result of this study was <strong>the</strong> Long Term Control <strong>Plan</strong>, or LTCP, which<br />

describes measures to be taken to improve <strong>the</strong> water quality in <strong>the</strong> James River by<br />

making modifications to <strong>the</strong> CSO. Two phases have already been completed, at a cost of<br />

$242 million, and <strong>the</strong>se ef<strong>for</strong>ts have led to an increase in <strong>the</strong> water quality when<br />

measured by bacteriological standards (Greeley and Hansen, 2006). Phase III of <strong>the</strong><br />

project calls <strong>for</strong>, among o<strong>the</strong>r improvements, <strong>the</strong> construction of new conveyance pipes<br />

that would reduce (but not remove) <strong>the</strong> combined sewage overflows into Gillies Creek to<br />

4 times a year.<br />

Figure 14. Location of Combined Sewer Overflows Into Gillies Creek<br />

source: City of Richmond Department of Public Utilities<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 22

1.5 Building Conditions<br />

Building conditions on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site were evaluated using criteria developed<br />

by Peter Dunbar and Associates (see Appendix <strong>for</strong> detailed description). Dunbar’s<br />

criterion has three ratings (sound, deteriorating, and dilapidated) <strong>for</strong> structures based on<br />

<strong>the</strong> number of deficiencies <strong>the</strong> structure possesses. There are only 6 structures in <strong>the</strong><br />

entire study area: five on <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site, and one that is being used by<br />

a bus repair company.<br />

According to City of Richmond tax records, <strong>the</strong> corrugated metal building used by<br />

Newton’s Bus Service (see Figure 15) was constructed in 1988. The building is<br />

considered one story tall, though it appears taller since it is built to accommodate<br />

commercial buses. Though <strong>the</strong> building is not significant architecturally, it is in sound<br />

condition.<br />

The gas works has not been used <strong>for</strong> decades, and although <strong>the</strong> site has been fenced off,<br />

vandals and natural deterioration have left <strong>the</strong>ir mark on <strong>the</strong> buildings. The five structures<br />

that remain on <strong>the</strong> site of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> (please refer back to Figure 5) are <strong>the</strong> 600,000<br />

cubic foot gasometer; <strong>the</strong> building containing <strong>the</strong> office, blacksmith shop and machine<br />

shop; <strong>the</strong> building containing <strong>the</strong> boiler house, compressor, and exhauster house; <strong>the</strong><br />

retort house; and <strong>the</strong> steam generating plant located along Williamsburg Avenue.<br />

The gasometer (see Figure 16) was <strong>the</strong> device that held <strong>the</strong> gas after it was produced and<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e it got piped out to <strong>the</strong> customers. This is perhaps <strong>the</strong> most noticeable structure on<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> site because it is several stories tall but its purpose remains a mystery to<br />

<strong>the</strong> observer. The gasometer worked like a collapsible cup that might be used on a<br />

camping trip. There are large cylindrical rings at <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> structure (thus why <strong>the</strong><br />

ground is raised below <strong>the</strong> gasometer) and a metal lid on top (see Figure 17). When<br />

enough gas was produced, one of <strong>the</strong> cylinders would rise out of <strong>the</strong> ground, and when<br />

<strong>the</strong> gasometer was full, <strong>the</strong> whole collapsible structure would rise up to <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong><br />

steel frame.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> gasometer remains intact, it has not been used <strong>for</strong> decades, and its structural<br />

integrity is unknown. It does not appear to have suffered much degradation, however, a<br />

mechanical room underneath <strong>the</strong> gasometer has filled up with rainwater. The Dunbar<br />

criteria were not applied to this structure since it was not able to be viewed.<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 23

Figure 15. Newton’s Bus Service Building on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong><br />

Figure 16. <strong>Gas</strong>ometer at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> <strong>Site</strong><br />

source: photograph by <strong>the</strong> author<br />

source: photograph by <strong>the</strong> author<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 24

Figure 17. The Top of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong>ometer<br />

source: photograph by <strong>the</strong> author<br />

The remaining four buildings of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong> are in deteriorated or dilapidated<br />

condition according to <strong>the</strong> Dunbar criteria. Natural deterioration and vandalism have left<br />

<strong>the</strong> buildings containing <strong>the</strong> office, blacksmith shop and machine shop; <strong>the</strong> boiler house,<br />

compressor, and exhauster house; and <strong>the</strong> retort house with enough deficiencies to<br />

qualify as dilapidated. The steam generator building is in slightly better condition than<br />

<strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> buildings, and as such is in dilapidated condition. The distressed state of<br />

<strong>the</strong> buildings, however, should not detract from <strong>the</strong> possibility of reusing <strong>the</strong>se buildings<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Slavery Museum.<br />

A preliminary analysis based on Department of Public Utilities maps and interviews with<br />

DPU staff indicate that several if not all of <strong>the</strong>se buildings date to <strong>the</strong> founding of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gas</strong><br />

<strong>Works</strong> on this site in <strong>the</strong> 1850s. The architectural detail, though utilitarian, tells its own<br />

story in a way that new construction often lacks, and <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>se buildings may<br />

date to a time when slavery still existed, and was in fact employed at this site, would<br />

make a strong connection to <strong>the</strong> proposed use. (see Figures 18 through 25).<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />

<strong>Site</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 25

Figure 18. Building Containing <strong>the</strong> Office, Blacksmith Shop, and Machine Shop<br />

source: photograph by <strong>the</strong> author<br />

Figure 19. Building Containing <strong>the</strong> Office, Blacksmith Shop, and Machine Shop<br />

source: photograph by <strong>the</strong> author<br />

<strong>Fulton</strong> <strong>Gas</strong> <strong>Works</strong><br />