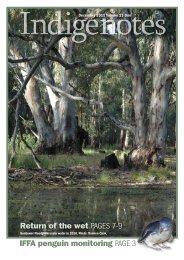

Indigenotes - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Indigenotes - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Indigenotes - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

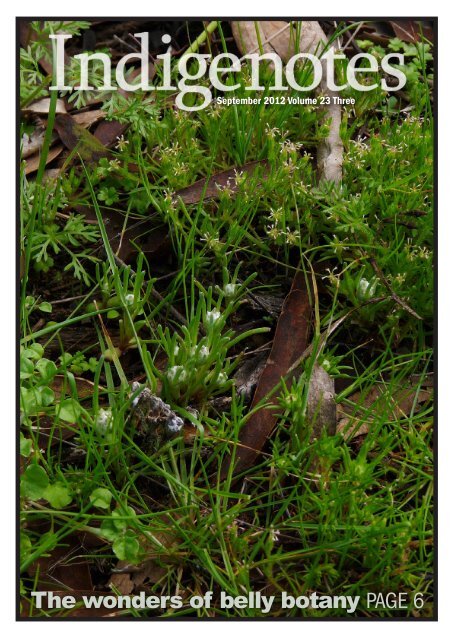

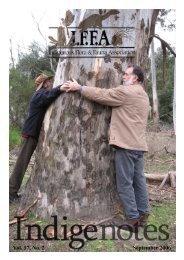

September 2012 Volume 23 Three<br />

The INDIGENOTES VOLUME wonders 23 NUMBER 3 of belly botany PAGE 6

Presidents letter<br />

Places you love<br />

A<br />

new campaign urges us to make our voice heard for biodiversity<br />

conservation. The Places You Love campaign is being run by an alliance of<br />

conservation groups. It aims to counter a corporate-led attack on Australia’s<br />

conservation laws.<br />

At the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) meeting of state <strong>and</strong><br />

federal governments earlier this year, business had special access through the<br />

COAG ‘Business Advisory Forum’. This unprecedented access was granted to<br />

no other sector of Australian civil society. The business lobbies’ clamour to slash<br />

environmental protection found a willing ear among many governments. They<br />

were quick to adopt the belittling label ‘green tape’ to describe environmental<br />

laws. On 13 April 2012, COAG announced its intention to ‘streamline’ both<br />

federal <strong>and</strong> state environmental laws across Australia with a particular emphasis<br />

on environmental assessment processes. This effectively h<strong>and</strong>s state <strong>and</strong> territory<br />

governments the power to assess <strong>and</strong> approve projects in their state, removing<br />

the federal government’s current <strong>and</strong> very important oversight role. In particular,<br />

there is an intention to nobble the Environment Protection <strong>and</strong> Biodiversity<br />

Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act) which has seriously advanced conservation<br />

in this country over the last decade.<br />

Imperfect as they are, our environmental laws have provided brakes to our<br />

nation’s hurtling race to destroy nature. I have witnessed many instances where<br />

Federal laws have had more ‘teeth’ than State legislation <strong>and</strong> have been critical<br />

to conservation victories. The Places You Love campaign is providing a means to<br />

collectively express our very clear support for these laws. The IFFA committee<br />

supports the aims of the conservation group alliance <strong>and</strong> this initiative.<br />

I urge members to become informed, add your voice <strong>and</strong> spread the word about<br />

this campaign. At the website below you can upload photos of places you want to<br />

protect <strong>and</strong> find templates for letters to send to your local members <strong>and</strong> the PM.<br />

Don’t be silent, nature needs your voice.<br />

http://placesyoulove.org/<br />

IFFA & SPIFFA<br />

OUTING<br />

Cranbourne<br />

Botanic Gardens<br />

27th October 11am<br />

Join our Southern Peninsula IFFA brethren<br />

for a heathl<strong>and</strong> walk <strong>and</strong> lunch at<br />

Cranbourne Botanic Gardens.<br />

Meet at 11am in the Stringybark Picnic<br />

Area (Melways map 133K12) for a walk<br />

through the heathl<strong>and</strong>s at the site.<br />

We will lunch at around 1pm.<br />

Those who are interested can then either<br />

do a walk in another part of the<br />

heathl<strong>and</strong> or go to the formal part of the<br />

gardens for the Australian Garden walk at<br />

around 2pm.”<br />

Bookings are not required, but inquiries<br />

can be made to Fam Charko on<br />

0402519124, or bookings@iffa.org.au.<br />

IFFA’s trip to Nardoo Hills was a great<br />

success, <strong>and</strong> will be written up for the<br />

next issue of <strong>Indigenotes</strong>.<br />

Review<br />

Life in a gall. The biology <strong>and</strong> ecology of insects that live in plant galls.<br />

Rosalind Blanche. CSIRO Publishing 2012, 70 pages<br />

When walking in the bush with others, I am frequently asked about the lumps,<br />

bumps <strong>and</strong> miniature sculptures that adorn our gums <strong>and</strong> wattles <strong>and</strong> other plants.<br />

Up till now, I have only been able to answer questions in general terms, aware I was<br />

missing out on a world of stories hidden within these galls. In my garden, one kind<br />

of Gall-wasp helps by pollinating delicious figs while the Citrus Gall Wasp deprives<br />

me of lemons<br />

Rosalind Blanche’s slender book is a perfect introduction to this fascinating<br />

world. The range of different invertebrates (as well as fungi, viruses,<br />

nematode worms <strong>and</strong> others) that creates galls was a revelation.<br />

Examples of the diverse life cycles <strong>and</strong> ecologies inside these structures<br />

are efficiently related in the easy to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> copiously illustrated<br />

text. I was particularly struck by the social life of gall-forming thrips<br />

which form miniature hives<br />

The galls’ effect on native plants used in commerce was another<br />

interesting story – with studies on the local ecology of galls used to<br />

design biological control program overseas. Blanche completes this book<br />

with a practical chapter on how you can study galls for yourself <strong>and</strong> the<br />

inspiring story of a Canberra primary School project that contributed to<br />

the discovery <strong>and</strong> naming of a wasp with a unique gall lifecycle.<br />

I heartily recommend this book to both the beginner <strong>and</strong> experienced<br />

amateur naturalist alike, it shows there is a whole realm of intriguing<br />

complexity waiting to be found in any bushl<strong>and</strong> or backyard.<br />

Reviewed by Brian Bainbridge.<br />

2<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

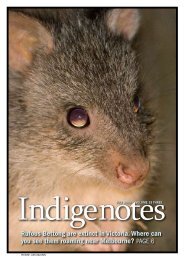

Dingy Swallowtail or<br />

Small Citrus Butterfly,<br />

Papilio anactus.<br />

Mick Connolly<br />

utterflies <strong>and</strong> habitat restoration<br />

What sets a lepidopteran heart aflutter? What sort of gr<strong>and</strong> design<br />

builds into butterfly habitat? The simple planting of lom<strong>and</strong>ra is not<br />

enough, explains Ian Faithfull<br />

John Reid’s article in <strong>Indigenotes</strong> 23:2 concentrates on<br />

the particular food plants of butterfly species, <strong>and</strong> advocates<br />

their establishment as a method of conserving <strong>and</strong> restoring<br />

butterfly populations. Although such plantings are a fundamental<br />

requirement, this is an oversimplified approach since butterflies,<br />

like other animals, require much more than food.<br />

Yen (2011 p. 205) summarised the situation this way: “In<br />

most cases, there is an emphasis on recreating pre-European<br />

settlement habitats .. . <strong>and</strong> [this] often only involves planting<br />

known food plants, especially of butterflies, in the hope that<br />

they will be colonised.”<br />

Historical records<br />

Firstly, as Braby (1989) remarked, there were at that time<br />

few studies that provided a reasonably complete picture of the<br />

butterfly fauna of any specific region or habitat in Victoria. Little<br />

has subsequently changed. Published historical information on<br />

the Melbourne fauna is scarce <strong>and</strong> consists mostly of isolated<br />

records of species of particular interest because of their rarity,<br />

abundance, unseasonal occurrence, etc. There are few published<br />

accounts of the faunas in particular areas of Melbourne. Examples<br />

include the fauna of LaTrobe University (Braby 1989), Yarra<br />

Bend (Faithfull 1992) <strong>and</strong> Wattle Park, Burwood (Braby <strong>and</strong><br />

Berg 1987 1989, Faithfull 1989 1993). Accounts may appear in<br />

local newsletters, ecological survey reports etc. but these tend to<br />

be even less accessible.<br />

The Dunn <strong>and</strong> Dunn (2006) butterfly database has good<br />

Victorian coverage <strong>and</strong> enables compilation of faunas for<br />

particular areas based on actual distribution point records,<br />

however information is not available for many localities in<br />

the Melbourne area. In contrast, the maps in Braby (2000)<br />

generally extrapolate the range of a species to cover areas<br />

between known distribution points <strong>and</strong> thus may be grossly<br />

misleading if used to assemble a species list for a particular<br />

locality. The Atlas of Victorian Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Museum of<br />

Victoria databases also contain butterfly records <strong>and</strong> should be<br />

consulted if seeking to compile local area information. Lack of<br />

adequate historical documentation of the local fauna means the<br />

effects of restoration efforts cannot be objectively assessed <strong>and</strong><br />

there appears to be little evidence that restoration plantings<br />

or butterfly gardening in the Melbourne region have had any<br />

butterfly conservation benefits. Tons of Lom<strong>and</strong>ra longifolia<br />

have been planted, but I am floundering to come up with any<br />

documentation of its utilisation.<br />

Flavours in favour<br />

Secondly, current underst<strong>and</strong>ings of known food plants of<br />

a butterfly species are incomplete <strong>and</strong> knowledge continues to<br />

exp<strong>and</strong>. According to Common <strong>and</strong> Waterhouse (1981) the<br />

food plants of the Australian Admiral, Vanessa itea, on mainl<strong>and</strong><br />

Australia were species of Urtica (stinging nettles), but the food<br />

plant list now includes two Parietaria species (Braby 2000).<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 3

Butterflies <strong>and</strong> habitat restoration Continued from page 3<br />

It may well be the plant species assumed to be a host in<br />

a particular area is not a host, <strong>and</strong> in some cases the actual<br />

favoured host may await discovery. In many cases with<br />

Melbourne butterflies, the actual hosts are exotic species,<br />

e.g. Ehrharta erecta is commonly utilised by the Common<br />

Brown, Heteronympha merope, in Melbourne (Braby<br />

2000). Melbourne is probably very similar to the City of<br />

Davis, California, where non-indigenous food plants, both<br />

cultivated <strong>and</strong> naturalised are very important for the diverse,<br />

highly valued butterfly fauna, so much so the objectives of<br />

butterfly conservationists conflict with those of plant-focused<br />

restorationists <strong>and</strong> weed controllers (Shapiro 2002).<br />

Habitat <strong>and</strong> microhabitat<br />

Thirdly, as any entomologist will attest, patches of<br />

apparently suitable food plants are usually not inhabited. The<br />

precise factors that make for good habitat are generally poorly<br />

known. Breeding populations may shift from habitat patch<br />

to habitat patch, or remain in one<br />

habitat patch for many years without<br />

neighbouring patches being colonised.<br />

Many other factors beside the<br />

presence of the food plant determine<br />

the suitability of the habitat for a<br />

particular butterfly species. Many of<br />

the blues (Lycaenidae) have symbiotic<br />

relationships with ants, which protect <strong>and</strong> guard larvae <strong>and</strong><br />

pupae. Eggs may not be laid if ants of the appropriate taxa<br />

are not present, or if laid, the larvae may be exterminated by<br />

predators without ants to guard them.<br />

Suitable temperatures (often measured as accumulated<br />

‘degree-days’) are very important for the development of<br />

the juvenile stages of Lepidoptera. In particular the extent<br />

to which the plants are exposed to sunlight has differential<br />

importance for different species.<br />

Food plants in shaded positions at a particular time of day<br />

in a particular season may never be colonised because the<br />

fertilised adult female won’t fly there. The larval webs of Delias<br />

harpalyce are almost always on the sunny side of a mistletoe<br />

clump, <strong>and</strong> Ogyris species pupate under the bark on the sunny<br />

side of a tree (K. Dunn, pers. comm.), so mistletoes in shaded<br />

areas are less likely to be successfully utilised.<br />

With other butterfly species, like the grass-feeding<br />

Heteronympha merope, shade of some type appears to be<br />

necessary: open grassl<strong>and</strong>s are just not suitable for it.<br />

Moisture conditions are also important, both for plant<br />

growth, since larvae usually require fresh, palatable food during<br />

their development, <strong>and</strong> because excessive humidity or dryness<br />

will have adverse effects on survival of juvenile stages.<br />

Food plants may be rejected if their foliage contains<br />

inadequate levels of essential nutrients, or particular<br />

biochemical constituents that might be characteristic of<br />

varieties of a plant species that are oviposition deterrents or<br />

toxic to larvae. Adult butterflies require nectar, <strong>and</strong> often feed<br />

on other liquids such as fluids in puddles, dung, tree sap,<br />

etc. If suitable adult food <strong>and</strong> watering requirements are not<br />

present in the vicinity of a planting then colonisation will be<br />

unlikely.<br />

Adult butterflies utilise flight spaces <strong>and</strong> perches that tend to<br />

be species specific. For example, a male butterfly may require a<br />

suitable open area in a particular height range to patrol if it is<br />

to remain in the area.<br />

Many butterflies require areas of bare ground on which to<br />

bask, so over-thorough revegetation that fills all the spaces can<br />

be detrimental to them.<br />

The importance of microhabitats is generally poorly<br />

understood, as are a range of other habitat factors. Many<br />

skipper butterflies (Hesperiidae), for example, oviposit not<br />

on the host itself but on leaf litter near the food plant (Braby<br />

2000), so absence of such litter might preclude establishment.<br />

Some species often pupate off the food plant, e.g. under the<br />

bark of nearby trees, so restoration efforts must take this into<br />

consideration.<br />

Factors such as chemical pollution, artificial lights <strong>and</strong><br />

anthropic noise levels may well have an impact. Disruptive<br />

wind patterns such as those produced by vehicle traffic along<br />

major roads possibly disrupt butterflies sufficiently to preclude<br />

their establishment in roadside plantings.<br />

Patches of apparently suitable food plants are usually not<br />

inhabited . . . Breeding populations may shift from habitat<br />

patch to habitat patch, or remain in one habitat patch for<br />

many years without neighbouring patches being colonised.<br />

The role of predators <strong>and</strong> parasites in the limitation of<br />

butterfly populations is poorly understood, but it seems likely<br />

that in some areas the presence of a particular predator (e.g.<br />

an exotic ant species) could prejudice the survival of juvenile<br />

butterfly populations.<br />

Recolonisation <strong>and</strong> reintroduction<br />

Finally, the food plants must be found by adult female<br />

butterflies in order to be colonised. Since many species<br />

disperse poorly, that may never happen once a butterfly species<br />

has disappeared from an area.<br />

What constitutes a suitable dispersal corridor for nonmigrant<br />

butterflies has generally never been established for<br />

Victorian species. Adults of the Swordgrass Brown, Tisiphone<br />

abeona, seem rarely to venture far into open areas <strong>and</strong> may<br />

require continuous canopy at least 2 m high with plenty of<br />

flight space beneath. Reintroductions of butterflies (this is<br />

usually effective only with juvenile stages) may be required, but<br />

such translocations have various potential problems, similar to<br />

those with which most readers will be familiar in the context<br />

of plants, such as the risk of genetic pollution if provenances<br />

are not understood, <strong>and</strong> the choice of an unsuitable ecotype<br />

for introduction.<br />

Monitoring <strong>and</strong> documentation<br />

So there is a need to document <strong>and</strong> publish local area<br />

butterfly species lists <strong>and</strong> known local food plants, with<br />

details of the condition of the vegetation during the period of<br />

observations. This at least will enable some future assessment<br />

of the success of plantings in regard to butterfly diversity.<br />

Where revegetation programs are believed to have been<br />

successful at providing habitat for butterflies this information<br />

needs to be recorded <strong>and</strong> compiled. Casual records of<br />

single or a few species will be difficult to publish but could<br />

be submitted to the Atlas of Victorian Wildlife or may be<br />

4<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

Review<br />

Intelligent Tinkering<br />

Bridging the gap between Science <strong>and</strong> Practice<br />

Robert J. Cabin<br />

Society for Ecological Restoration<br />

Isl<strong>and</strong> Press, Washington<br />

Distributed in Australia by CSIRO Publishing<br />

‘Intelligent tinkering’ was the term used by the famous<br />

ecologist, Aldo Leopold, over sixty years ago to describe his<br />

explorations into restoration of degraded prairie l<strong>and</strong>. The<br />

casual approach this term suggests is still the dominant<br />

mode of knowledge-building among ecological restoration<br />

practitioners.<br />

Cabin, a trained ecologist, explains how scientists are often<br />

frustrated by practitioner’s perceived reluctance to employ formal<br />

scientific processes. Cabin has also experienced practitioner’s<br />

disgust at collaborations with scientists that result in findings they<br />

regard as obvious or irrelevant.<br />

In this thought-provoking book, Cabin has attempted to unravel<br />

the issues that underlie this problem. These range from the<br />

self-evident to deep philosophical divides. Cabin explains that<br />

classic science investigations attempt to prove general rules, while<br />

locally developed projects are concerned with site peculiarities. In<br />

many cases this means investigations critical to the practitioner<br />

are of no interest to a scientist <strong>and</strong> vice versa. Thus scientists<br />

become perceived as out-of-touch<br />

<strong>and</strong> practitioners <strong>and</strong> their work<br />

are dismissed as ‘un-scientific’<br />

<strong>and</strong> a hindrance to ‘doing things<br />

right’. This is disastrous for projects<br />

based on collaboration <strong>and</strong> Cabin’s<br />

book is a plea for scientists <strong>and</strong><br />

practitioners to find common<br />

ground <strong>and</strong> respect for each other’s<br />

strengths.<br />

Cabin’s book is illustrated by his<br />

fascinating work in the restoration<br />

of a ‘basket-case’ ecosystem; the<br />

dry forests of Hawaii. National <strong>and</strong> cultural peculiarities are<br />

occasionally apparent but the joys <strong>and</strong> frustrations will be familiar<br />

to many in Australian restoration projects. Among minor quibbles,<br />

I occasionally felt that Cabin under-estimated the scientific basis<br />

of the intuition <strong>and</strong> ‘art’ of practitioners.<br />

While the problem this book addresses may seem very specific,<br />

it h<strong>and</strong>icaps progress of thous<strong>and</strong>s of projects to conserve our<br />

biodiversity. Professionals, volunteers <strong>and</strong> academics seeking to<br />

combine their efforts will benefit from the variety of perspectives<br />

that Cabin brings to light.<br />

Brian Bainbridge<br />

Butterflies <strong>and</strong> habitat restoration Continued from page 4<br />

acceptable to K.L. Dunn for the Dunn <strong>and</strong> Dunn butterfly<br />

database (which is operated entirely without government<br />

support). The Victorian Entomologist (Entomological Society of<br />

Victoria) is the most active purveyor of butterfly information<br />

in Victoria <strong>and</strong> may be an option for publishing more detailed<br />

information <strong>and</strong> species lists. What is really needed are modern<br />

Wiki databases that enable the build-up of information by<br />

multiple observers over time. However such systems tend to<br />

have quality control issues (notably unreliable observers <strong>and</strong><br />

incorrect species identifications) if not strictly overseen. In<br />

all cases the minimal information that should be recorded<br />

includes the date <strong>and</strong> time of the observation, the locality <strong>and</strong><br />

GPS reading, the butterfly species <strong>and</strong> life stage, the number of<br />

individuals <strong>and</strong> the details of the habitat.<br />

Long term biodiversity monitoring requires dedication, since<br />

it is not going to be paid for by governments. Ideally what<br />

is required is more than casual observation. Transect or belt<br />

surveys, where the numbers of individual butterfly adults seen<br />

along a defined transect are counted by experienced observers,<br />

are a good method to establish baseline data for a site. Regular<br />

repetition of a survey over a number of years (pre to postreveg)<br />

should enable an assessment to be made of the effects<br />

of the restoration efforts on butterflies. But bear in mind<br />

that some species may require more specialised monitoring<br />

techniques. When planning or undertaking revegetation<br />

work, the particular contexts of the plantings — the other<br />

butterfly habitat factors — need at least to be considered in<br />

terms of what is known about a particular butterfly species’<br />

requirements. It is worth stressing the survival of a particular<br />

butterfly species in a particular locality might possibly be<br />

prejudiced by zealous weed eradication programs or other<br />

features of the rehabilitation program. As is the case with spiny<br />

weeds <strong>and</strong> small birds, one needs to establish suitable native<br />

habitat plants before eradication takes place.<br />

And finally, much more needs to be known about the<br />

peculiar habitat requirements of butterfly species before a<br />

meaningful prediction can be made about whether a particular<br />

planting will be beneficial. Revegetation efforts that fail to<br />

result in butterfly establishment thus have the potential to yield<br />

lessons for future activity.<br />

References<br />

Braby, M.F. (2000) Butterflies of Australia. Their Identification,<br />

Biology <strong>and</strong> Distribution. CSIRO, Collingwood.<br />

Braby, M.F. & Berg, G.N. (1987) A preliminary search for Trapezites<br />

symmomus Hubner at Wattle Park, with notes on other species.<br />

Victorian Entomologist 17, 49-51.<br />

Braby, M.F. & Berg, G.N. (1989). Further notes on butterflies at<br />

Wattle Park, Burwood. Victorian Entomologist 19, 38-42.<br />

Braby, M.F. (1989) The butterfly fauna of La Trobe University, Victoria.<br />

Victorian Naturalist 106,118-132.<br />

Common, I.F.B. <strong>and</strong> Waterhouse, D.F. (1981) Butterflies of Australia.<br />

Revised Edn., Angus & Robertson, Sydney.<br />

Dunn, K.L. <strong>and</strong> Dunn, L.E. (2006) Review of Australian Butterflies<br />

1991. Annotated Version. (CD-ROM), K.L. & L.E. Dunn, Melbourne.<br />

Faithfull, I. (1989) Two additional Wattle Park butterflies.<br />

Victorian Entomologist 19(5), 86.<br />

Faithfull, I. (1992) Butterflies at Yarra Bend 1983-90.<br />

Victorian Naturalist 109:162-167.<br />

Faithfull, I. (1993) Common Imperial Blue, Jalmenus evagoras<br />

evagoras (Donovan), an additional Wattle Park butterfly.<br />

Victorian Entomologist 23(2), 34.<br />

Shapiro, A.M. (2002) The California urban butterfly fauna is<br />

dependent on alien plants. Diversity <strong>and</strong> Distributions 8, 31-40.<br />

Yen, A.L. (2011) Melbourne’s terrestrial invertebrate biodiversity:<br />

losses, gains <strong>and</strong> the new perspective. Victorian Naturalist 128(5),<br />

201-208.<br />

Further reading<br />

New, T.R. (1997) Butterfly Conservation. 2nd Edn., Oxford University<br />

Press, Melbourne.<br />

Samways, M.J. (2005) Insect Biodiversity Conservation. Cambridge<br />

University Press, Cambridge, U.K.<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 5

The wonders of<br />

belly botany<br />

In the bush right now there are<br />

plenty of wondrous signs that<br />

early spring is upon us. The wattles<br />

are flowering profusely, cuckoos<br />

have begun calling, orchids are<br />

in bud <strong>and</strong> many birds are busily<br />

preparing their nests (while<br />

nervously eyeing off the cuckoos).<br />

But there is one exciting spring<br />

phenomena that is not only overlooked<br />

by most people, but is<br />

rudely stepped upon with little<br />

notice. This, reports Karl Just, is<br />

the tiny world of the ‘inch flora’.<br />

Inch flora makes up a suite of fascinating<br />

species that, as the name suggests, hardly grow taller than<br />

an inch (or 2.54 centimeters to be exact).<br />

Victoria has over 50 species of inch flora, depending on how<br />

you define them. Here I refer to winter-spring active herbs,<br />

fern allies <strong>and</strong> sedges that usually grow to less than an inch<br />

high. The majority of the group are annuals, although several<br />

are also perennial species that re-shoot from underground<br />

rhizomes each season. The largest diversity are distributed in<br />

the central <strong>and</strong> western drier parts of the state while they are<br />

rare to absent from denser forest <strong>and</strong> scrub. This distributional<br />

6<br />

pattern is a reflection of their fascinating ecology.<br />

The inch flora commonly grow in small communities in<br />

suitable habitat, creating a dazzling mix of shapes <strong>and</strong> colours.<br />

The largest patches are associated with relatively open habitats<br />

growing in beds of moss, often on shallow soil platforms over<br />

rock where the soil is too shallow for larger plants. They are<br />

also found wherever there is plenty of light, moisture <strong>and</strong><br />

space in a variety of grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> woodl<strong>and</strong>s. Moss cover<br />

appears to be vital for many inch flora, as it captures <strong>and</strong><br />

holds moisture as well as securing a thin layer of soil. The<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

COVER PHOTO<br />

Multiple species of belly flora pictured near Stawell in September 2010<br />

by Brian Bainbridge.<br />

1 A miniature Triglochin growing in the state’s far north-west.<br />

Photo by Damien Cook.<br />

2 Small Wrinklewort, Siloxerus multiflorus, growing amongst the moss<br />

Triquetrella papillata. Photo by Karl Just.<br />

3 A small party of inch flora, showing Small Wrinklewort, Siloxerus<br />

multiflorus, Flannel Cudweed, Actinobole uliginosum, Stonecrop<br />

Crassula sieberiana, Common Bow-flower, Millotia muelleri.<br />

Photo by Karl Just.<br />

local distribution of some members of the group appears to<br />

be influenced by grazing pressure <strong>and</strong> tree clearing, both of<br />

which open up otherwise dense habitat, allowing greater light<br />

exposure. At our place in Fryerstown I have noticed some<br />

species to only occur in previously cleared areas with high<br />

kangaroo grazing pressure. I also know of a few great inch flora<br />

communities underneath power-line easements where the<br />

vegetation is occasionally slashed.<br />

Like many therophytes (annuals), the inch flora are<br />

extraordinarily well adapted to Australia’s unpredictable<br />

rainfall. Over the hotter months they remain dormant in<br />

seed-form, in the soil or tucked beneath<br />

the moss which is also withered <strong>and</strong><br />

inactive. At this time their habitat can<br />

be a harsh place, with extreme surface<br />

temperatures <strong>and</strong> desiccating winds. As<br />

the seasons change, winter rains kick-start<br />

these ecosystems, as the moss exp<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> tiny soaks begin to seep out of the<br />

rocks <strong>and</strong> soil. In wet years there can be a<br />

mass of germination of inch flora, many<br />

which survive to flower <strong>and</strong> set plenty<br />

of seed. John Morgan <strong>and</strong> co. from La<br />

Trobe University have discovered some<br />

fascinating seed traits of many inch flora,<br />

such as the presence of ‘myxospermy’.<br />

This is when the seed is coated in a kind<br />

of dry mucilage that hydrates <strong>and</strong> swells<br />

rapidly on contact with water. Morgan<br />

has suggested this ‘assists the seed to attach<br />

to the soil, giving the radicle something<br />

to push against as it starts to elongate,<br />

minimizing the risk of pushing the root hair zone away from<br />

the soil surface’. With the return of warmer weather the<br />

population begins to die off, completing the annual cycle.<br />

During dry years the germination <strong>and</strong>/or persistence of<br />

the inch flora is much reduced. It is possible that many seeds<br />

don’t germinate in dry years, as this would risk depleting the<br />

seed bank. However if good rains are followed by dry weather<br />

later in spring, this can lead to a decline of the population.<br />

If they are lucky they replenish the seed bank during the wet<br />

years – a classic cycle of boom <strong>and</strong> bust. Further study would<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 7

Congratulations, Stephen!<br />

The Queen’s Birthday honours, this year, have given Friends<br />

of the Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne members reason<br />

to celebrate. Stephen Hopper was awarded Australia’s<br />

highest honour, Companion of the Order of Australia (AC), for<br />

“eminent service as a global science leader in the field of plant<br />

conservation biology, particularly in the delivery of world class<br />

research programs contributing to the conservation of endangered<br />

species <strong>and</strong> ecosystems”.<br />

Professor Stephen Hopper, FLS, AC, has had an enduring<br />

interest in Australian plants <strong>and</strong> his many publications include<br />

Threatened <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> Orchids of Western Australia, 2008. When<br />

he spoke at FRBGC’s annual dinner in May 2003 he was CEO of<br />

Botanic Gardens <strong>and</strong> Parks Authority, WA, which embraces Kings<br />

Park <strong>and</strong> Botanic Garden <strong>and</strong> the indigenous annexe Bold Park.<br />

In 2006 he became the first non-British person appointed<br />

Director, CEO <strong>and</strong> Chief Scientist, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK.<br />

In October this year he will return to a research position in WA. In<br />

July 2011 he addressed a combined meeting of FRBG Melbourne<br />

<strong>and</strong> FRBG Cranbourne. His illustrated address Old l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

Reveal New Perspectives which derived from his research into the<br />

world’s Oldest Climatically Buffered Infertile L<strong>and</strong>scapes which is<br />

now known as the OCBIL theory.<br />

An endearing attribute of this extraordinary scientist is his<br />

willingness <strong>and</strong> ability to engage with anyone interested in plants<br />

or natural history. In 2003 Warren Worboys wrote:<br />

“To spend time with Stephen in the bush is not only a botanical<br />

experience of the highest degree but you are likely to garner plenty<br />

of information on all aspects of natural history. Steve does not<br />

have a narrow focus in biological science. His field journals are<br />

not only crammed with information but they are a work of art<br />

in themselves with many beautiful sketches of plants <strong>and</strong> other<br />

aspects of his studies”.<br />

It is extremely heartening to see that at long last botany <strong>and</strong><br />

ecology are now on the same platform as medicine <strong>and</strong> other<br />

sciences when Companion of the Order of Australia honours are<br />

awarded.<br />

Alex Smart <strong>and</strong> Rodger Elliot<br />

INCH FLORA CONTINUED FROM PAGE 7<br />

be very valuable to provide more insight into these population<br />

dynamics.<br />

In Victoria the inch flora diversity is dominated by the<br />

Asteraceae family (one of the most diverse families in the<br />

world). Some of the Asteraceae inch flora include Common<br />

Sunray, Triptilodiscus pygmaeus (affectionately known as Tripto-the-disco<br />

by some), a species that has become pretty rare<br />

throughout basalt grassl<strong>and</strong> around Melbourne, <strong>and</strong> which is<br />

also found throughout grassy woodl<strong>and</strong>s, grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> rocky<br />

outcrops in moss mats. Other species include the Bow-flowers,<br />

Millotia spp., Small Wrinklewort, Siloxerus multiflorus, Sticky<br />

Long-heads, Podotheca angustifolia <strong>and</strong> Cup-flowers, Gnephosis<br />

spp. I suspect that one reason this family has so successfully<br />

colonised the spring-soak niche is its ability to disperse over<br />

long distances. When your habitat is equally tiny <strong>and</strong> scattered<br />

in disjunct patches, you need some pretty good dispersal<br />

mechanisms.<br />

The Crassulaceae also has a few tiny members, all within<br />

the Crassula genus, while one of the most surprising members<br />

of the inch flora is Triglochin. Most people would be familiar<br />

with this genus as the robust aquatic macrophyte, but there are<br />

several tiny species that grow in spring-soaks from the coast to<br />

the semi-arid inl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

I have seen a few growing in soaks on s<strong>and</strong> dunes in the mallee<br />

— a great place for many inch flora.<br />

Pygmy Club-moss, Phylloglossum drummondii, is another<br />

fascinating species. Unlike the majority of more recently<br />

evolved inch flora, it is very ancient, being a member of one of<br />

the most primitive plant families, the Huperziaceae. While its<br />

relatives once grew in the forests <strong>and</strong> swamps of Gondwana,<br />

Pygmy Club-moss is today found in wet, heathy habitats.<br />

Austral Adders Tongue’s, Ophioglossum spp., is another cool<br />

little ancient member, so called because the spore-bearing stalk<br />

is thought to resemble a snake’s tongue. Apparently it has the<br />

highest chromosome count of any organism (1,262 compared<br />

to humans’ 46 – now there’s a r<strong>and</strong>om fact). Then there are<br />

8<br />

the miniature<br />

Stylidiums . . . but<br />

I could go on all<br />

day.<br />

Many of<br />

Victoria’s inch flora<br />

are potentially<br />

threatened by a<br />

range of processes.<br />

At one moss bed<br />

I have monitored<br />

in Eltham for<br />

over six years,<br />

there has been a<br />

noticeable decline<br />

of many species<br />

due to drought<br />

<strong>and</strong> damage by<br />

bikes, cars <strong>and</strong><br />

walkers. Predicted<br />

global climate<br />

change could be<br />

bad news for the<br />

group, as their<br />

The tiny fern ally, Austral Adders Tongue,<br />

Ophioglossum lusitanicum.<br />

Photo by Chris Lindorff, courtesy of<br />

NatureShare.<br />

habitat is highly dependent on adequate rains. Perhaps one of<br />

their biggest problems is their tiny size, as many humans don’t<br />

seem to notice or care for tiny things. But the importance<br />

of the inch flora should not be under-stated. Morgan has<br />

also pointed out that annual plants make up to 40% of<br />

the diversity of some of our most diverse ecosystems – the<br />

woodl<strong>and</strong>s of western Victoria. The inch flora <strong>and</strong> their<br />

slightly larger annual cousins are therefore a key component of<br />

the biological diversity of these areas.<br />

So next time you’re out in the bush this spring, check out<br />

the moss mats – you never know what you might see. There’s a<br />

whole world down there to be explored.<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

Biodiverse sustainable revegetation<br />

Where ground is fully<br />

covered by vegetation,<br />

seeds have little<br />

opportunity to become<br />

established plants<br />

because they are unable<br />

to successfully compete<br />

for vital resources.<br />

Jill Dawson looks at this<br />

important attribute of<br />

vegetation <strong>and</strong> hopes<br />

to prompt further<br />

discussion.<br />

A patch of native vegetation<br />

of high quality has few weeds<br />

<strong>and</strong> a weedy area has few<br />

native species. If revegetation<br />

can achieve full cover of native<br />

vegetation it will require almost<br />

no maintenance weeding <strong>and</strong><br />

thus is a sustainable outcome.<br />

Achieving this depends upon<br />

many factors, one of the most<br />

important being the condition<br />

of the topsoil seed bank. In the<br />

article I discuss some options<br />

in the choice to be made on<br />

whether it is more feasible or<br />

beneficial to recover or smother<br />

the topsoil seed bank.<br />

I also propose that a tree is<br />

planted with all life forms surrounding it to ensure sustainability<br />

through biodiversity in the creation of a healthy ecosystem.<br />

I draw attention to the importance of creating ground level<br />

habitat with woodchip mulch or similar plus rocks <strong>and</strong> logs if<br />

feasible. The conclusion I propose is that biodiverse sustainable<br />

revegetation should aim to achieve full native vegetation cover in<br />

3 to 5 years.<br />

When I take students or trainees into the bush with<br />

me, I ask them to look at how many weeds there<br />

are. Always, in ‘good bush’, there are few or no<br />

weeds. All the ground space is taken up with plants or leaf<br />

litter. There isn’t room for weeds to invade. This is a stable,<br />

sustainable ecosystem protected from weed invasion. It is<br />

biodiverse. It is also enormously pretty with flowers <strong>and</strong><br />

fragrances.<br />

I have spent much time weeding around native plants on<br />

revegetation sites. Weeding is tiresome <strong>and</strong> expensive. I look<br />

at many revegetation sites, years old, <strong>and</strong> see trees, shrubs<br />

<strong>and</strong> weeds. No native grasses, daisies, lilies or orchids. Low<br />

biodiversity. It is the converse of above, as there isn’t room for<br />

natives.<br />

In paddocks I see lone gum trees, hung with pendulous<br />

clumps of mistletoe, dying. There are no trees close by to bring<br />

the possums that graze on mistletoe; no daisies <strong>and</strong> other herbs<br />

to attract wasps <strong>and</strong> other invertebrates whose larvae feed on<br />

mistletoe, so this parasite<br />

is uncontrolled. The<br />

ecosystem is unbalanced.<br />

Gum trees live for some<br />

hundreds of years. An<br />

isolated tree may appear<br />

healthy for perhaps 100 or<br />

200 years but eventually<br />

the stress from lack of soil<br />

biota, leaf grazers <strong>and</strong> their<br />

predators, normally found<br />

in a biodiverse ecosystem,<br />

will have an impact. The<br />

mistletoe – gum-tree<br />

interrelationship shows<br />

that tree death will follow<br />

this ecosystem imbalance.<br />

The life expectancy<br />

<strong>and</strong> good health of a<br />

tree is dependent on the<br />

biodiversity of its floral<br />

community, especially<br />

ground covers.<br />

What is a successful<br />

revegetation<br />

project?<br />

A successful revegetation<br />

project establishes a<br />

biodiverse ecosystem <strong>and</strong><br />

becomes sustainable. An<br />

ecosystem is a complete<br />

community of living<br />

organisms <strong>and</strong> the<br />

nonliving materials of their surroundings. It includes plants,<br />

animals, <strong>and</strong> microorganisms; soil, rocks, <strong>and</strong> minerals as well<br />

as surrounding water sources <strong>and</strong> the local atmosphere.<br />

A successful revegetation project has few weeds. Planting is<br />

the easy part; volunteers are enthusiastic planters on public or<br />

private l<strong>and</strong>. But who is going to weed? How much money<br />

is available for how many years to keep on weeding? If funds<br />

are limited, then revegetation projects should be designed to<br />

minimise maintenance.<br />

Most weeds come from the topsoil. Seeds accumulate in the<br />

soil over years, commonly millions per cubic metre in what is<br />

called the topsoil seed bank.<br />

In the design of a revegetation project, I look at the state of<br />

that topsoil seed bank. Does it have potential to provide native<br />

plant regeneration, or is it likely to provide continued weed<br />

seed germination <strong>and</strong> therefore weed cover.<br />

Recover or smother the top soil seed bank?<br />

Where the topsoil seed bank has potential for native plant<br />

regeneration, my preferred management option is to recover<br />

(or re-activate) that seed bank. Methods depend upon size <strong>and</strong><br />

state of site. Steps appropriate for large areas such as farms are<br />

to remove grazing, spring burn to remove annual weedy grasses<br />

<strong>and</strong> stimulate native seed germination, to spot spray or use a<br />

selective herbicide on broad-leaf <strong>and</strong> perennial grassy weeds<br />

<strong>and</strong> ‘crash graze’ at appropriate times.<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 9

Biodiverse sustainable revegetation<br />

Continued from page 9<br />

Native species that regenerate from these treatments<br />

can be increased <strong>and</strong> added to with broad acre<br />

mechanically assisted or h<strong>and</strong> direct seeding, along<br />

with some tubestock planting. Fences or tree guards<br />

protect plants from grazing.<br />

In an urban setting, site areas are generally smaller.<br />

Sites have not been grazed in many years <strong>and</strong> burning<br />

may not be not an appropriate treatment. In parks,<br />

open space areas, <strong>and</strong> public <strong>and</strong> private gardens,<br />

weed management is an important environmental <strong>and</strong><br />

civic amenity issue.<br />

On many sites, natural regeneration of native<br />

vegetation has been reduced to only a few species that<br />

compete with a high level of persistent weed cover.<br />

The topsoil seed bank is dominated by weed species.<br />

In this case the cost of continued maintenance by<br />

herbicide <strong>and</strong> slashing would be very high. Ground<br />

treatments with a residual herbicide will stop weed<br />

seed germination for some months but will degrade<br />

soil health. Smothering the seed bank may be the<br />

cheapest <strong>and</strong> one of the most effective <strong>and</strong> quickest<br />

ways to achieve a sustainable biodiverse result for a<br />

revegetation project. This method also has less risk<br />

of environmental impact <strong>and</strong> is more beneficial to<br />

worms than the use of chemical herbicides.<br />

Covering the ground with an organic material that<br />

prevents weed growth will substantially reduce maintenance<br />

requirements. If plantings can provide close to 100% native<br />

vegetation cover on the ground within a few years, then the<br />

plantings will be secure or protected from weed seeds that<br />

arrive by wind or flood. The revegetation will be stable <strong>and</strong><br />

require minimal maintenance.<br />

This may require staging revegetation on a site over several<br />

years. Incremental progress that is sustainable <strong>and</strong> requires<br />

low maintenance is preferable to a project being ab<strong>and</strong>oned<br />

because it is too much work or lacks funding for the level<br />

of maintenance required. It can be done, slowly, bit by bit<br />

without it being ‘lost’ to weeds. This has to be better than not<br />

doing it at all because it seems too ‘hard’.<br />

The best weed control is replacement with<br />

native plants, achieving close to 100%<br />

native vegetation cover as in ‘good bush’<br />

Biodiverse ecosystem establishment<br />

The best weed control is replacement with native plants,<br />

achieving close to 100% native vegetation cover as in ‘good<br />

bush’.<br />

A popular concept is to ‘shade out the grassy weeds by<br />

planting trees <strong>and</strong> shrubs.’ I have seen that grassy weed cover<br />

is reduced in biomass — height <strong>and</strong> density — but I have not<br />

seen any of this type of revegetation where the ground level<br />

understorey has regenerated in a weedy setting or that the<br />

revegetation has had more understorey life forms added later.<br />

It can be very difficult for ground cover species like grasses <strong>and</strong><br />

herbs to establish beneath mature trees.<br />

Planting trees <strong>and</strong> shrubs is a good first step in revegetation<br />

but to establish healthy ecosystems, all life forms - ground<br />

hugging spreaders, herbs, grasses, forbs, shrubs, ferns, mosses,<br />

10<br />

fungi etc<br />

— need to<br />

be included<br />

to make a<br />

complete<br />

community<br />

with a variety<br />

of habitats. No<br />

tree should be<br />

planted without<br />

its community<br />

surrounding it.<br />

The health of<br />

trees <strong>and</strong> shrubs<br />

depends upon<br />

a diversity of<br />

insects that are<br />

attracted to<br />

a diversity of<br />

plant species<br />

<strong>and</strong> life forms.<br />

Putting in<br />

all life forms<br />

at the same<br />

time is more<br />

effective because<br />

the trees <strong>and</strong> other plants adapt to the availability of water<br />

<strong>and</strong> nutrients as they grow. Additional planting of the same<br />

area later will bring weed seeds to the surface <strong>and</strong> therefore<br />

stimulate weed growth.<br />

Where the topsoil seed bank does not provide potential for<br />

native plant regeneration, an effective method to smother the<br />

seedbank <strong>and</strong> revegetate is to:<br />

• Slash weeds, add dolomite — this will create food for worms<br />

<strong>and</strong> other soil fauna,<br />

• Plant — each canopy tree species has a 5-10m radius<br />

surround of understorey with all life forms (except those<br />

which need shade such as some ground-hugging spreaders),<br />

• Cover ground with weed mat or newspapers or similar, <strong>and</strong><br />

• Cover mat or material with about 50mm woodchip mulch<br />

to prevent loss of soil moisture through wicking.<br />

To create or enhance a biodiverse ecosystem, providing<br />

habitat at ground level <strong>and</strong> below is vital. Healthy soil hosts a<br />

range of soil fauna which are likely vectors for dispersing the<br />

essential mycorrhizal fungi throughout the soil. Wood chip<br />

mulch is inhabited by insects <strong>and</strong> other invertebrates <strong>and</strong><br />

attracts soil fauna. It also presents well in an urban or garden<br />

setting. There will be little fire fuel risk with newspaper plus<br />

mulch as it should retain some moisture <strong>and</strong> there is limited<br />

oxygen available for a ground level fire. Birds <strong>and</strong> lizards will<br />

be attracted to the insects.<br />

The revegetation method described above will establish a<br />

long-term, low maintenance biodiverse ecosystem patch. It can<br />

be used simply as a small patch or isl<strong>and</strong> in a weedy l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

In time <strong>and</strong> with weed control of the surrounds the isl<strong>and</strong><br />

might be joined together with other isl<strong>and</strong>s to make a larger<br />

native vegetation patch, wildlife corridor or join with a core<br />

reserve or park. This method is especially useful on sites that<br />

have great variability, with some parts much easier to work<br />

on than others. It is also an effective way to link with existing<br />

native vegetation.<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

Revegetation materials costs<br />

Most projects include plant guards <strong>and</strong> stakes for plant<br />

protection at significant additional cost. I suggest that in many<br />

projects guards are not necessary <strong>and</strong> funds could instead be<br />

used to purchase weed mat <strong>and</strong> mulch.<br />

Native grasses, ground-hugging spreaders, lilies <strong>and</strong> many<br />

other ground cover plants are generally not attractive to<br />

grazers <strong>and</strong> do not require guards unless the site has a very<br />

high population of rabbits, kangaroos or other grazers. In that<br />

case the grazers should be controlled before revegetation is<br />

attempted.<br />

Guards can protect plants from grazing by rabbits or<br />

kangaroos but nurseries can add a gritty deterrent coating to<br />

seedlings to prevent grazing. Guards produce a microclimate<br />

within the guard that shields the plant from wind, however,<br />

plants with strong root development should already have<br />

the resilience to be planted without such protection. This<br />

microclimate may weaken the stem <strong>and</strong> development of the<br />

support or structural roots of the tree or shrub.<br />

Within the guards is also an ideal environment for increased<br />

weed growth. It is quite difficult to remove these weeds, <strong>and</strong><br />

adds to the maintenance cost.<br />

Guards make it easier to spray between plants but if the<br />

topsoil seed bank of weeds has been smothered, then there is<br />

almost no weed growth between plants.<br />

With such reduced maintenance, funds could be allocated<br />

to weed mat <strong>and</strong> mulch. Many Shires are now producing<br />

weed free mulch available for projects at minimal or no cost.<br />

The other ‘thing’ with guards is that sometimes they don’t<br />

get removed…or in the case of use on creeks <strong>and</strong> rivers, they<br />

can add to the detritus from flooding.<br />

Thanks to the many people who have shared with me their<br />

concerns on how we revegetate. This article is a compilation<br />

that I hope will prompt further discussion. Special thanks to<br />

Belinda Pearce, Trevor Danger <strong>and</strong> Tony Marsh.<br />

Editors’ note: Jill’s approach may not suit all environments <strong>and</strong><br />

feedback on this article is welcome. Readers who have registered<br />

on the IFFA website <strong>and</strong> are logged in can leave comments on the<br />

website version of this article<br />

http://www.iffa.org.au/biodiverse-sustainable-revegetation<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

http://www.iffa.org.au<br />

Incorporated <strong>Association</strong> No: A0015723B<br />

Office Bearers<br />

President: Brian Bainbridge, 7 Jukes Rd Fawkner 3060 (03)<br />

9359 0290(ah) email: president@iffa.org.au<br />

Vice-President: Vanessa Craigie, email: vicepres@iffa.org.au<br />

94973730 (ah).<br />

Secretary: Michele Arundell PO Box 77, Kallista 3791.<br />

(03) 9755 3347 (ah) email: secretary@iffa.org.au<br />

Treasurer: Tania Sloan, 23 Harrison Street Brunswick East 3057,<br />

treasurer@iffa.org.au<br />

Public Officer: Peter Wlodarzyck, 0418 317 725<br />

email: publicofficer@iffa.org.au<br />

Events Coordinator: Fam Charko, activities@iffa.org.au<br />

0402 519 124<br />

Newsletter Editor: Tony Faithfull, (03) 9386 0264 (ah).<br />

21 Harrison St East Brunswick 3057. editor@iffa.org.au<br />

Webmaster: Vacant<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Nurseries Liaison Officer:<br />

Judy Allen, nurseries@iffa.org.au<br />

Student representative: Karen McGregor, student@iffa.org.au<br />

Fundraising Coordinator: vacant<br />

Ecological Information Coordinator:<br />

Karl Just, email: info@iffa.org.au<br />

Committee members: Liz Henry <strong>and</strong> Linda Bradburn<br />

Life member<br />

Patricia Crowley<br />

<strong>Indigenotes</strong> is the newsletter of the <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

The views expressed in <strong>Indigenotes</strong> are not necessarily those<br />

of the <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

Call for articles<br />

<strong>Indigenotes</strong> is a newsletter by IFFA members for IFFA members.<br />

Stories, snippets, photos <strong>and</strong> reports from members are always<br />

welcome.<br />

If it’s something you’re doing with flora or fauna or habitat, write it<br />

down <strong>and</strong> send it to IFFA’s editor at editor@iffa.org.au<br />

Membership<br />

$40 per annum for non-profit organizations,<br />

$50 per annum for corporations,<br />

$25 per annum for individuals, or $20 per annum concession,<br />

$35 per annum for families,<br />

$500 for individual life members or<br />

$700 for family life members.<br />

Membership includes<br />

4 issues of <strong>Indigenotes</strong> per year,<br />

•<br />

Occasional freebies or discounts<br />

Discount subscription to Ecological Management & Restoration<br />

Journal ($72, inc GST)<br />

Membership applications <strong>and</strong> renewals should be sent to<br />

21 Harrison St, Brunswick East, 3057<br />

Problems with membership renewals? Please contact<br />

Tony Faithfull on 93860264 or membership@iffa.org.au<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 11

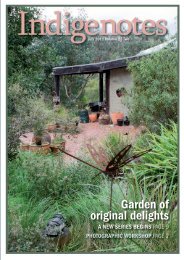

Wedding Bush, Ricinocarpos pinifolius, is spectacular in<br />

bloom. Masses of honey-scented, starry flowers flung over<br />

shrubs as tall as the best man <strong>and</strong> as wide as an in-law<br />

lying flat out on the dance floor. Cheering them on will be a<br />

crowd of attendant white-flowering tea-tree.<br />

Wedding Bush is so named because it was the bouquet of<br />

choice in early Melbourne. A wild colonial beau could head<br />

his horse into heathl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> happily return with saddle<br />

bags loaded with fragrant decoration. Today it is seen almost<br />

exclusivly at remnant sites <strong>and</strong> is practically impossible<br />

to propagate. Seed pods usually yield only well-fed bugs,<br />

most cuttings fail <strong>and</strong> the few seedlings that survive usually<br />

Contents<br />

President’s letter; IFFA excursion invitation;<br />

book review 2<br />

Butterflies <strong>and</strong> habitat restoration 3-5<br />

Book review 5<br />

struggle struggle. It is the most desired plant in local<br />

indigenous nurseries.<br />

Friends of the Grange Heathl<strong>and</strong> Reserve is hosting an open<br />

day <strong>and</strong> the marketing department (whose name is Thelma)<br />

has anounced the event is to be known as the Festival of<br />

Wedding Bush.<br />

Saturday October 13, 9am-noon.<br />

Osborne Avenue, Clayton South.<br />

Short walks, short talks, free S<strong>and</strong>belt plant <strong>and</strong> food.<br />

Enquiries: 0403 587 611<br />

Mick Connolly<br />

The wonders of belly botany 6-8<br />

Biodiverse sustainable revegetation 9-11<br />

Contact us 11<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC