Indigenotes - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Indigenotes - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Indigenotes - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

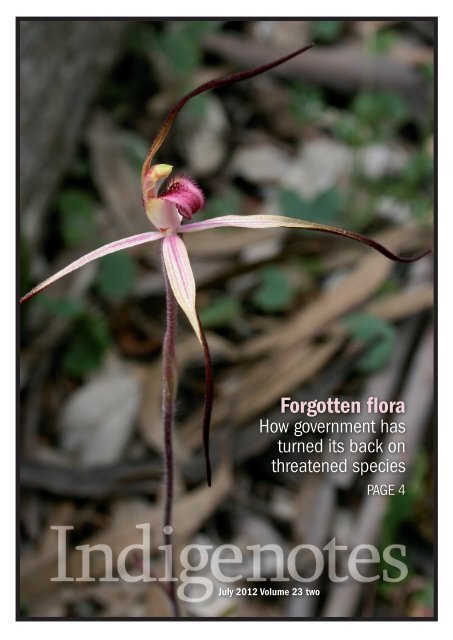

Forgotten flora<br />

How government has<br />

turned its back on<br />

threatened species<br />

PAGE 4<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2<br />

July 2012 Volume 23 two

Dianella being planted at Laverton Grassl<strong>and</strong>s to provide food for the bee that<br />

pollinates Diuris fragrantissima. Photo: Alex Smart.<br />

Orchids pictured on this <strong>and</strong> the following page are currently grown at the Horsham<br />

DSE Lab. All are threatened at national <strong>and</strong> state levels <strong>and</strong> listed under the<br />

Victorian <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> Guarantee Act.<br />

IFFA OUTING Bush Heritage<br />

Nardoo Hills Reserve<br />

19 August 2012 10.30am-3pm<br />

Non-members welcome<br />

Come <strong>and</strong> join Bush Heritage’s Victorian Reserves Manager<br />

Jeroen van Veen for an exclusive visit to Nardoo Hills Reserve.<br />

This 817 ha reserve supports a large diversity of vegetation<br />

communities including grey box grassy woodl<strong>and</strong>, boxironbark<br />

<strong>and</strong> mallee, providing vital habitats for a range of<br />

wildlife. Since Bush Heritage acquired the first property in<br />

2004 <strong>and</strong> actively managed it for conservation outcomes,<br />

the transformation has been remarkable.<br />

After an initial introduction over a cup of tea we will set off<br />

on foot to explore more of this wonderful property; taking in<br />

some of the key features <strong>and</strong> management practices. The<br />

terrain is rather rocky <strong>and</strong> hilly but the pace will be gentle<br />

to allow for plenty of looking <strong>and</strong> talking. We are likely to<br />

cover around 3-5km. Don’t forget to bring your cameras <strong>and</strong><br />

binoculars.<br />

Visit details: 10.30am – 3pm at reserve,<br />

reachable by 2WD, ~210km NW of<br />

Melbourne (allow 3hrs driving time),<br />

nearest town is Wedderburn 12km.<br />

We’ll organise a carpool for people who<br />

are without transport. Composting<br />

toilet on site. The cost of the tour will<br />

be a voluntary donation to the Bush<br />

Heritage Reserve.<br />

You will need: BYO all food <strong>and</strong><br />

drinks, reasonable level of fitness/<br />

mobility, arrange own transport to <strong>and</strong><br />

from the reserve (or carpool), wear<br />

comfortable clothing <strong>and</strong> sturdy foot<br />

wear for off-track walking.<br />

For bookings call Fam Charko<br />

04 02519124 or email:<br />

bookings@iffa.org.au.<br />

Please state your name, phone number, number of people<br />

attending <strong>and</strong> if you need a spot in the carpool. Some<br />

members may be staying overnight nearby; you may be<br />

interested too.<br />

5<br />

President’s letter<br />

1<br />

1 Diuris fragrantissima, Sunshine Diuris,<br />

intended for grassl<strong>and</strong>s on the edge of<br />

Melbourne. Photo: Alex Smart.<br />

In early May IFFA took part in a deputation to the<br />

Shadow Minister for the Environment, Lisa Neville.<br />

We joined concerned members of the public to express<br />

concern at the dismissal of Threatened Species Officers by the<br />

State Government under Ted Baillieu.<br />

In recent months IFFA has made a number of submissions<br />

to the State Government advising our objection to changes<br />

being made in l<strong>and</strong> management <strong>and</strong> species conservation.<br />

We are aware of further troubling proposals in the near future.<br />

There are many dedicated environmental advocacy groups;<br />

why should IFFA engage in political process?<br />

To put it simply, flora <strong>and</strong> fauna doesn’t have a vote, our<br />

members do.<br />

What will be the result of the dismissal of DSE <strong>and</strong> DPI<br />

officers?<br />

Loss of experienced officers contributes to<br />

scientific amnesia<br />

Results of long-term monitoring are crucial to virtually<br />

all threatened species conservation programs. Effective<br />

monitoring programs combine scientific rigour,<br />

meticulous record keeping <strong>and</strong> effective sharing of results<br />

in recognised forums. It is a skill-set that takes years to<br />

develop <strong>and</strong> will need to be redeveloped under a<br />

future government that recognizes the state’s<br />

moral <strong>and</strong> legal obligations to biodiversity<br />

conservation. What a waste.<br />

Lost support for volunteers<br />

The expertise <strong>and</strong> consistency of these officers<br />

supported <strong>and</strong> orchestrated volunteers who give massively<br />

of their time <strong>and</strong> energy. This ‘multiplier effect’ is apparently<br />

unrecognised by the recent cuts.<br />

CONTINUED PAGE 3<br />

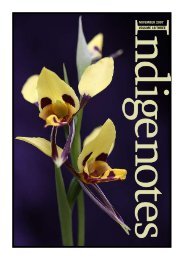

Cover image<br />

The C<strong>and</strong>y Spider-orchid, Caladenia versicolor.<br />

Photo David Pitts.<br />

2<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

2 3 4<br />

2 Caladenia hastata, Mellblom’s Spiderorchid.<br />

Photo: Len Carrigan.<br />

3 Caladenia xanthochila, Yellow-lip Spiderorchidwhich.<br />

Photo: Len Carrigan.<br />

What if flora <strong>and</strong> fauna had a vote?<br />

We have been repeatedly assured these cuts will not affect<br />

‘front-line workers’<br />

For Victoria’s flora <strong>and</strong> fauna, the threatened species officers<br />

are the ‘front line’ workers. Job losses are tragic for individuals<br />

but for endangered flora <strong>and</strong> fauna, such chopping <strong>and</strong><br />

changing can be terminal. Many species now rely on consistent<br />

effort to maintain <strong>and</strong> recover their habitats.<br />

Threatened species projects inspire hope<br />

<strong>and</strong> care for our environment’s future<br />

The genuine gains these projects achieve energise the public<br />

in the face of seemingly endless news of ecological decline.<br />

IFFA members are intensely concerned about these changes<br />

<strong>and</strong> related ones such as the starvation of our reserve system.<br />

The impact of neglected weed control programs on public l<strong>and</strong><br />

is a perennial issue of particular concern to rural l<strong>and</strong>holders<br />

conservationists alike. Cuts at DSE <strong>and</strong> DPI will starve weed<br />

programs. Timely <strong>and</strong> consistent treatment is essential in weed<br />

programs. Delay can lead to vastly increased expenditure a few<br />

years down the track. This is summed up in the old adage that<br />

‘one years seeds equals seven years weeds’ <strong>and</strong> these shortsighted<br />

cuts are sowing the seeds for years of ‘catch up’.<br />

If you disagree with the direction this government is taking,<br />

what can you do? Here are a few suggestions.<br />

• Identify <strong>and</strong> record the impact of these cuts on your local<br />

environment, local parks <strong>and</strong> volunteer groups.<br />

• Tell your local member of Parliament that you are unhappy<br />

with this direction <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> a response. Is the case<br />

‘newsworthy’? Ring up or write to your favourite newspaper.<br />

• Support <strong>and</strong> become active in groups addressing this issue.<br />

• Where these programs impact Nationally listed species <strong>and</strong><br />

communities, make sure your Federal member hears about<br />

it as well as the Federal Minister for the Environment, Tony<br />

Burke.<br />

• If you have worked with any staff that have been let go,<br />

ensure they know that their contribution has been valued.<br />

• Identify your allies, they may be found in unexpected<br />

4 Pterostylis xerophila, Desert Rustyhood.<br />

Photo: Len Carrigan.<br />

5 Thelymitra mackibbinii, Brilliant<br />

Sun-orchid. Photo: Len Carrigan.<br />

places. Many businesses involved in l<strong>and</strong> management will<br />

suffer from the lost support for their industry these cuts<br />

represent.<br />

Finally, remember to ‘nourish the soul’. Find time to be in<br />

nature <strong>and</strong> with friends. Strengthen yourself for your sake <strong>and</strong><br />

for the sake of the environment you are working to protect.<br />

Brian Bainbridge<br />

Further information: http://www.iffa.org.au/backwardsspiral-continues-baillieu-government-axes-threatenedspecies-officers<br />

6<br />

6 Caladenia fulva, Tawny Spider-orchid.<br />

Photo: Len Carrigan.<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2<br />

3

The forgotten flora<br />

How the Baillieu Government has<br />

turned its back on threatened species<br />

We pulled off the dusty track <strong>and</strong> parked the car<br />

under a gnarly young stringybark tree. Before us was<br />

a diverse heathy woodl<strong>and</strong>, alive with the colour of<br />

wildflowers in full spring bloom. In the distance I could see<br />

rugged s<strong>and</strong>stone escarpments, lined with dark stunted trees<br />

<strong>and</strong> ancient boulders.<br />

I was on a day trip in the Black Ranges, a westerly extension<br />

of the Grampians near Cherrypool. My travelling companions<br />

were David Pitts, a biodiversity officer for the DSE <strong>and</strong> Roger,<br />

one of DSE’s natural resource managers. Dave <strong>and</strong> I had spent<br />

the week searching <strong>and</strong> monitoring threatened plant species<br />

as part of Dave’s role with the DSE. Today we had headed<br />

out from our base at Horsham to meet Roger, an expert in<br />

the local country <strong>and</strong> its environment. Roger had seen some<br />

orchids out this way that he thought might interest us.<br />

‘This is the spot’, said Roger, <strong>and</strong> we headed into<br />

the bush. We immediately came across a large patch<br />

of beautiful white spider-orchids. These were the<br />

Large White Spider-orchid (Caladenia venusta),<br />

a species listed as vulnerable in Victoria. At most<br />

places this species has declined substantially, but<br />

here they seemed to be thriving. We found over a<br />

hundred, all in slightly different shades of colours<br />

<strong>and</strong> scattered throughout the bush. But then we<br />

saw an orchid that looked very different. We stooped down<br />

low to have a closer look, <strong>and</strong> became increasingly excited as<br />

we compared it to the Large White’s nearby. It was certainly<br />

different <strong>and</strong> looked suspiciously like the C<strong>and</strong>y Spider-orchid<br />

(Caladenia versicolor) a species only known from one other site<br />

in the world over at Lake Fyans. We stayed at the site for well<br />

over an hour, taking an abundance of photos <strong>and</strong> checking<br />

out other wildflowers <strong>and</strong> birds in the area, before heading<br />

for another site. Later in the day we were to discover several<br />

new populations of the nationally rare Elegant Spider-orchid<br />

(Caladenia formosa) before heading back to camp.<br />

The photos of our unusual orchid were sent to several<br />

experts <strong>and</strong> quickly confirmed as the C<strong>and</strong>y Spider-orchid,<br />

which is listed as threatened under the Victorian <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Fauna</strong> Guarantee Act, <strong>and</strong> considered endangered by DSE.<br />

It is listed as vulnerable under the Australian Environment<br />

Protection <strong>and</strong> Biodiversity Conservation Act. This population<br />

was the second disjunct population of only two. Over the<br />

next twelve months Dave worked busily on this population<br />

<strong>and</strong> managed to collect enough seed to send to the DSE<br />

laboratory in Horsham. There, Dr Noushka Reiter <strong>and</strong> her<br />

team managed to successfully propagate the species, a huge<br />

break-through in the recovery work. A back-up population<br />

of the plants was now available <strong>and</strong> the species could be reintroduced<br />

into another suitable site if considered appropriate<br />

by the orchid advisory committee.<br />

Sounds inspiring doesn’t it? Well this is where the Baillieu<br />

Government steps in. Several months ago David Pitts,<br />

Noushka Reiter <strong>and</strong> nine other DSE biodiversity officers in<br />

the south-west Victoria region were told to get ready to pack<br />

their bags, as their contracts would not be renewed. The<br />

recovery programs that these dedicated <strong>and</strong> highly trained<br />

staff had been working on for years would now grind to a<br />

halt. What of the seven thous<strong>and</strong> rare orchids sitting in the<br />

Horsham laboratory waiting to be re-introduced to the wild?<br />

‘Who cares?’ seems to be the Baillieu government’s response.<br />

Orchids weren’t the only plants the DSE officers had been<br />

working on either. A large assemblage of nationally endangered<br />

plants had been under their close management, from salt<br />

lake shrubs, wetl<strong>and</strong> herbs to annual grasses. No one is now<br />

available to look after these species in the south-west region,<br />

other than the already over-worked remaining staff.<br />

The Victorian Government has strong legal obligations<br />

to manage our threatened species under global agreements<br />

(the United Nations ‘Convention on Biological Diversity’,<br />

of which Australia is a signatory), National legislation (the<br />

Environment Protection <strong>and</strong> Biodiversity Conservation Act)<br />

What of the seven thous<strong>and</strong> rare orchids<br />

sitting in the Horsham laboratory waiting<br />

to be re-introduced to the wild?<br />

‘Who cares?’ seems to be the Baillieu<br />

government’s response.<br />

<strong>and</strong> State legislation (the <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> Guarantee Act). Just<br />

like the cattle grazing in the alpine national parks, which was<br />

effectively a breach of several acts of parliament, the Baillieu<br />

Government seems to have no worries disregarding the law<br />

when pursuing its hollow agenda.<br />

IFFA has been actively campaigning against this issue, with<br />

letters written to the Liberals <strong>and</strong> visits to the Shadow Minister<br />

for the Environment. The response to our letter was shamefully<br />

inadequate, <strong>and</strong> failed to answer any of our concerns.<br />

Predicted global climate change is going to create a tough<br />

time for our natural ecosystems to say the least. It is imperative<br />

that now more than ever our leaders should be assisting l<strong>and</strong><br />

managers to build the ecological resilience of our l<strong>and</strong>scapes,<br />

so that they are as able as possible to adapt to the coming<br />

changes. The failure of leadership shown by the Baillieu<br />

Government is shameful, with over $130 million cut from the<br />

environment department in the recent budget. I can only hope<br />

that more voices will continue to join in the fight against such<br />

irresponsible government, <strong>and</strong> help to protect our precious<br />

<strong>and</strong> highly stressed environment.<br />

Karl Just<br />

Editors Note: Since this article was written, <strong>and</strong> partly due to<br />

community pressure, the Wimmera Catchment Management<br />

Authority (CMA) has stepped in to save the orchid lab <strong>and</strong> to take<br />

over many of the orchid recovery plans. With union help a h<strong>and</strong>ful<br />

of DSE staff have managed to save their jobs. However things are<br />

still looking grim. Many front-line workers in DSE, the CMA <strong>and</strong><br />

the Department of Primary Industries (DPI) across Victoria have<br />

lost their jobs in the cost-cutting blitz, <strong>and</strong> many budgets cut. This<br />

will have massive implications for environmental management.<br />

DSE has announced that it will be moving to rely on volunteers<br />

for much of their work, a ridiculous scenario considering the huge<br />

level of time <strong>and</strong> experience required.<br />

4<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

Think local, act www<br />

http://natureshare.org.au<br />

NatureShare is a new website which stores information<br />

about indigenous species in Victoria. Anyone can<br />

upload observations to share with the world.<br />

It also provides for ‘collections’ of information relating to a<br />

specific area.<br />

All species known in Victoria to be remnant or selfsustaining<br />

(i.e. plants, weeds, animals <strong>and</strong> introduced animals,<br />

but not plants in revegetation sites, garden plants, pets, etc)<br />

will be included. This currently includes plants, mammals,<br />

birds, frogs, snakes <strong>and</strong> lizards, butterflies, dragonflies <strong>and</strong><br />

grasshoppers; other groups are being added over time.<br />

Once a species is listed, users can add observations <strong>and</strong><br />

create their own ‘collections’. A collection is essentially a<br />

species list, usually with observations, for a specific area.<br />

Observations can be accompanied by a photograph, but need<br />

not be. Tags such as ‘flower’, ‘leaf’, ‘juvenile’ etc are important<br />

elements which allow for searching for particular observations<br />

of a species.<br />

New users need to register <strong>and</strong> login, set up their username<br />

<strong>and</strong> profile, ‘join’ a collection, or create their own collection<br />

<strong>and</strong> then observations can be uploaded.<br />

How does the sharing part of NatureShare work?<br />

Photos are shared across collections; if a species list is<br />

added to a new collection, photos from other collections<br />

are automatically shared with the new collection, instantly<br />

generating the beginnings of a photo-based e-book. Then,<br />

as new photos are collected at the site <strong>and</strong> added to the<br />

collection, those new photos take precedence over shared<br />

photos. At the moment about 50% of the species have photos<br />

attached.<br />

Once you enter ‘biological attributes’ into NatureShare, they<br />

are shared for all to use. This means, if biological attributes<br />

are already entered in NatureShare prior to a collection<br />

being established the new collection becomes immediately<br />

searchable. Most importantly, once attributes are entered, they<br />

are in NatureShare forever <strong>and</strong> there is no need for individuals<br />

<strong>and</strong> groups to ‘reinvent the wheel’ on their existing website.<br />

NatureShare makes photos <strong>and</strong> other information available<br />

for any use (eg. books, newsletters, articles) so long as credit is<br />

given under a Creative Commons attribution scheme.<br />

Many individuals <strong>and</strong> groups regularly go on excursions/<br />

walks <strong>and</strong> make lists <strong>and</strong> photos of what they see. This<br />

information can be shared on NatureShare.<br />

If you think of a new feature for NatureShare you can build<br />

it yourself (or apply for grants to pay for someone to build<br />

it for you). NatureShare is an OpenGL web 2.0 application,<br />

which means code is freely available.<br />

NatureShare is a project conceived, designed <strong>and</strong><br />

implemented by Reilly Beacom <strong>and</strong> Russell Best <strong>and</strong> was<br />

launched in August 2011. It was funded by Riddells Creek<br />

L<strong>and</strong>care, APS Keilor Plains <strong>and</strong> DSE’s Vision for Werribee<br />

Plains project, with the addition of an extraordinary amount<br />

of volunteer <strong>and</strong> in-kind support from people <strong>and</strong> groups<br />

in Riddells Creek, the Macedon Range, across the Keilor-<br />

Werribee plains <strong>and</strong> beyond.<br />

will effectively be NatureShare 2.0 may be up<br />

What <strong>and</strong> running soon. NatureShare has effectively been<br />

taken up by Atlas of Living Australia, who have funded<br />

Museum Victoria to incorporate it into a bigger system they<br />

are calling ‘Bowerbird’. Russell Best is hopeful that this will<br />

take over from the current version of NatureShare. “Basically<br />

the Museum/ALA wanted a NatureShare-like system <strong>and</strong> they<br />

had already developed the stuff we were going to do in the<br />

next 10 years within the Museum’s biosecurity system, so they<br />

are putting it all together, effectively replacing biosecurity with<br />

biodiversity for this system. It will have, I hope, everything<br />

that is in NatureShare but also include all the things that are<br />

currently not great, like excellent communication systems,<br />

mapping, better searchability, <strong>and</strong> many more bells <strong>and</strong><br />

whistles, the ability to set up virtual groups, <strong>and</strong> including one<br />

or probably two apps for iphone <strong>and</strong> ipad”.<br />

NatureShare provides a long-needed resource for compiling<br />

observations of species occurrence <strong>and</strong> ecology in Victoria.<br />

However features that IFFA members may find lacking in the<br />

current implementation include:<br />

• There is potentially a lot of data with not much<br />

interpretation. For example the site does not include a<br />

general description of species.<br />

• The site is not an identification guide although you<br />

can compare photos already on the website with your<br />

observation.<br />

• The site does not deal with revegetation either in the sense<br />

of including observations of revegetated species, or in terms<br />

of including information on how to propagate or<br />

re-establish a species.<br />

• There is little emphasis on how species interact.<br />

• The site as it st<strong>and</strong>s is not particularly inviting for the<br />

general member of the public to learn about their local<br />

indigenous species.<br />

These functions might be added to the site in future, so in<br />

the meantime IFFA’s web pages on flora <strong>and</strong> fauna species will<br />

remain, <strong>and</strong> members are encouraged to contribute to these as<br />

well as to NatureShare. We will endeavour to include a link to<br />

the NatureShare species record in each of our species pages.<br />

Tony Faithfull<br />

Much of the information in this article is drawn from the<br />

NatureShare website or information kindly provided by Russell Best.<br />

Eclectic Parrot lives again<br />

Older <strong>Indigenotes</strong> readers will recall the excellent radio show<br />

The Eclectic Parrot which covered issues to do with the<br />

conservation <strong>and</strong> management of local <strong>and</strong> Australian flora,<br />

fauna <strong>and</strong> ecosystems. Bob McDonald who used to organise the<br />

show has recently been in touch: “I am trying to put together The<br />

Eclectic Parrot online — just building the site now at:<br />

www.eclecticparrot.com.au<br />

I will hopefully have online broadcasts in the next couple of<br />

months. My main project for the last couple of years has been<br />

getting up an underwater observatory for the Port Welshpool Long<br />

Jetty — see the link on my website.”<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2 5

Wood white or Spotted Jezebel,<br />

Delias aganippe.<br />

Photo Brian Bainbridge.<br />

Butterflies<br />

in the suburbs<br />

Native butterflies drift lazily through your backyard on sunny spring <strong>and</strong> summer<br />

days. Ever wondered where they come from? Did some all-powerful super-being<br />

create them spontaneously from thin air <strong>and</strong> drop them in your garden? Why have<br />

they come to 27 Smith Street, Elwood? What are they doing? asked John Reid.<br />

Butterflies like nectar. Nectar from all kinds of<br />

flowers, indigenous <strong>and</strong> exotic. The carbohydrates<br />

contained in this nectar help them to live longer, give<br />

them the strength to find a mate <strong>and</strong> breed successfully,<br />

enabling the females to produce lots of viable eggs.<br />

So it seems our adult butterflies are happy with many of<br />

the plants we serve them up in those crazy, chaotic, jumbled<br />

collections of flora we surround our houses with. But adult<br />

butterflies are essentially breeders, <strong>and</strong> as we have seen, they<br />

appear to be fairly unspecific in their choice of plants to provide<br />

strength-giving nectar. It is when the eggs hatch out to produce<br />

caterpillars (larvae), that the crucial feeding stage begins. And it<br />

is this stage that we must be most aware of if we are to conserve<br />

indigenous butterflies.<br />

Like all indigenous fauna, butterflies require the correct habitat<br />

in which to live. In particular, this habitat must provide them<br />

with particular larval food plants. When the female butterfly is<br />

ready to lay eggs, her sense of smell is probably stimulated by the<br />

essential oils of the plant species on which the larvae can feed.<br />

Regardless of the nature of this stimulation, she usually lays her<br />

eggs on or near certain preferred plants. This ensures that when<br />

the eggs hatch, the young caterpillars will be on or close to the<br />

plant they want to start munching straight away.<br />

That’s enough of the preliminary waffle: now for the guts<br />

6<br />

of the article. We are all l<strong>and</strong> managers in our own way,<br />

professional or otherwise. We can all have input into the way<br />

our indigenous flora <strong>and</strong> fauna are managed. For example, in<br />

suburban Melbourne we can get involved in our own gardens,<br />

in council reserves, bits of bush along the roadsides,<br />

railway lines, creeks <strong>and</strong> gullies, etc. As lovers<br />

of indigenous flora <strong>and</strong> fauna, let’s<br />

have some input on behalf of the<br />

caterpillars of our native<br />

butterflies.<br />

Klugs or Marbled<br />

Xenica,<br />

Geitoneura<br />

klugii.<br />

Ian Faithfull<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

1 Varied Sword-grass Brown<br />

Tisiphone abeona albifascia,<br />

Inkpot. Ian Faithfull<br />

2 Imperial Hairstreak, Jalmenus<br />

evagoras, with attendant<br />

Iridomyrmex ants, La Trobe<br />

sanctuary. Mick Connolly<br />

3 Imperial Jezebel, Delias<br />

harpalyce, larvae Amyema<br />

pendulum, KTRI Frankston.<br />

Ian Faithfull<br />

4 Broad-margined Azure, Ogyris<br />

olane, reared ex pupa, Dergholm.<br />

Ian Faithfull.<br />

Spiny-headed Mat-rush (Lom<strong>and</strong>ra longifolia), a common<br />

local tussock of the grasstree family, is the food plant for at<br />

least two species that occur around Melbourne: the Splendid<br />

Ochre or Symmomus Skipper (Trapezites symmomus), <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Barred or Dispar Skipper (Dispar compacta). Wattle Mat-rush<br />

(L. filiformis) is eaten by the Montane Ochre or Phigalioides<br />

Skipper (T. phigalioides).<br />

Native grasses are particularly valuable as butterfly habitat.<br />

There are at least seven other Melbourne butterflies that<br />

feed exclusively on grasses such as Kangaroo Grass (Themeda<br />

tri<strong>and</strong>ra), Blue Tussock Grass (Poa poiformis) <strong>and</strong> Slender<br />

Tussock Grass (P. tenera). These include the Common Brown<br />

(Heteronympha merope), Shouldered Brown (H. penelope),<br />

Ringed Xenica (Geitoneura acantha) <strong>and</strong> Klugs or Marbled<br />

Xenica (G. klugii).<br />

The general public doesn’t seem to be particularly enamoured<br />

by our parasitic (shock! horror!) native mistletoes. But we must<br />

tell all those who don’t love these plants that as well as a host of<br />

other ecological values, they provide larval food for at least four<br />

Melbourne butterflies: the Imperial White or Imperial Jezebel<br />

4<br />

CONTINUED PAGE 8<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2 7

Butterflies in the suburbs<br />

(Delias harpalyce), Wood White or Spotted Jezebel (Delias<br />

aganippe), Olane or Broad-margined Azure (Ogyris olane) <strong>and</strong><br />

Dark Purple Azure (O. abrota).<br />

The Imperial White is a particularly beautiful insect, black<br />

<strong>and</strong> white on the uppersides of its wings with splashes of red<br />

<strong>and</strong> yellow against a dark background on the undersides.<br />

Around Melbourne it usually has two generations each year.<br />

The adult butterflies fly around looking spectacular between<br />

September <strong>and</strong> November, then a second generation hatches<br />

in February <strong>and</strong> flies till April. Their caterpillars feed on the<br />

leaves of various mistletoes. In the suburbs of Melbourne<br />

these include Creeping Mistletoe (Muellerina eucalyptoides),<br />

Drooping Mistletoe (Amyema pendulum) <strong>and</strong> Box Mistletoe<br />

(A. miquelii).<br />

Two of our local Saw-sedges (Gahnia sieberiana <strong>and</strong> G.<br />

radula) are excellent butterfly plants, providing food <strong>and</strong><br />

shelter for the larvae of the Sword-grass Brown (Tisiphone<br />

abeona), Donnya or Varied Sedge-skipper (Hesperilla<br />

donnysa) <strong>and</strong> Spotted Sedge-skipper (H. ornata). If we can<br />

both preserve <strong>and</strong> re-establish these two sedges within the<br />

appropriate vegetation associations along verges <strong>and</strong> in<br />

bushl<strong>and</strong> remnants, these three butterflies may continue to fly<br />

in the suburbs of Melbourne.<br />

Another h<strong>and</strong>some butterfly of the Melbourne area is<br />

the Australian or Yellow Admiral (Vanessa itea), black <strong>and</strong><br />

rich port wine coloured with a large cream patch on each<br />

forewing. Its caterpillars feed at night on the leaves of the<br />

native Scrub Nettle (Urtica incisa). During the day they hide<br />

in a shelter made by joining a couple of the nettle leaves with<br />

a few str<strong>and</strong>s of silk.<br />

Along D<strong>and</strong>enong Creek in Heathmont, there still occurs*<br />

at least one colony of the Common Imperial Blue or Imperial<br />

Hairstreak (Jalmenus evagoras). They have survived in this<br />

area because two of their food plants, Black Wattle (Acacia<br />

mearnsii) <strong>and</strong> Silver Wattle (A. dealbata) have been retained<br />

near the creek. Here the larvae <strong>and</strong> pupae are attended by<br />

swarms of small black Iridomyrmex ants. The ants harvest<br />

sweet secretions from the larvae <strong>and</strong> pupae, <strong>and</strong> presumably<br />

return some degree of protection from predators. I have found<br />

colonies of the Common Imperial Blue in Mount Waverley,<br />

Vermont South, Donvale <strong>and</strong> Warr<strong>and</strong>yte.<br />

The Common Grass-blue (Zizina labradus) is regarded as<br />

the most abundant butterfly in Australia. The caterpillars feed<br />

on the young leaves, flower buds <strong>and</strong> seed-pods of various<br />

pea flowered plants. Around Melbourne, they probably<br />

feed largely on introduced legumes such as White Clover<br />

(Trifolium repens) <strong>and</strong> Lotus species, but many indigenous<br />

species have been recorded as food, including species of<br />

Desmodium, Swainsona <strong>and</strong> Indigofera. The Two-spotted<br />

Line-blue (Nacaduba biocellata), is a smaller but prettier<br />

butterfly with larvae that feed on the flowers of a large<br />

number of Acacia species.<br />

Another group of much maligned indigenous Melbourne<br />

plants are the Dodder Laurels (Cassytha spp.). They are often<br />

thought of as straggly <strong>and</strong> untidy, <strong>and</strong> of course like the<br />

mistletoes they are p-p-parasitic! As well as growing in dense<br />

tangles that provide safe places for native birds to nest, they<br />

are also the food plant of the larvae of the Common Duskyblue<br />

(C<strong>and</strong>alides hyacinthina). I have found these caterpillars<br />

on one of the Dodder Laurels, probably Cassytha melantha, in<br />

8<br />

open forest dominated by Red Box, Long-leaf Box <strong>and</strong> Red<br />

Stringybark in Warr<strong>and</strong>yte <strong>and</strong> Park Orchards.<br />

There are other indigenous butterflies <strong>and</strong> indigenous<br />

butterfly food-plants in the Melbourne area, but this lot will<br />

do for a start. It is hoped that this article will stimulate further<br />

discussion by IFFA, on how we can promote public awareness<br />

of all indigenous invertebrate animals <strong>and</strong> their habitat<br />

requirements.<br />

This article was originally published in <strong>Indigenotes</strong><br />

Newsletter No. 4 September 1986. IFFA intends to<br />

re-publish a series of articles which the late John Reid wrote<br />

for <strong>Indigenotes</strong> during 1986 <strong>and</strong> 1987, in recognition of his<br />

contribution to advancing our knowledge <strong>and</strong> protection of our<br />

indigenous flora <strong>and</strong> fauna. Thanks also to Graeme Lorimer<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ian Faithfull for updates <strong>and</strong> corrections to the article.<br />

Michele Arundell, IFFA Secretary.<br />

Notes from Graeme Lorimer<br />

*Imperial Blues (now called Imperial Hairstreaks, for<br />

international consistency) in central southern Victoria were<br />

decimated during the drought. Their host plants are mainly<br />

Blackwoods, Silver Wattles <strong>and</strong> Black Wattles, which also<br />

suffered badly in the drought. Blackwoods in the eastern<br />

suburbs were reduced to a few percent of their pre-drought<br />

numbers <strong>and</strong> became sickly, so it’s no wonder the butterflies<br />

plummeted, too. The wattles have recovered spectacularly<br />

<strong>and</strong> I started to see Imperial Hairstreaks in the eastern<br />

suburbs again over the past two summers. I haven’t seen any<br />

specifically in Heathmont but I am confident that they will<br />

return there if they haven’t yet.<br />

Most other butterfly species mentioned in John’s article<br />

also have newer names, as listed below.<br />

Old name<br />

Current terminology<br />

Symmomus Skipper<br />

Splendid Ochre<br />

Phigalioides Skipper<br />

Montane Ochre<br />

Dispar Skipper<br />

Barred Skipper<br />

Klug’s Xenica<br />

Marbled Xenica<br />

Imperial White<br />

Imperial Jezebel<br />

Wood White<br />

Spotted Jezebel<br />

Olane Azure<br />

Broad-margined Azure<br />

Sword-grass Brown<br />

Varied Sword-grass Brown<br />

Donnysa Skipper<br />

Varied Sedge-skipper<br />

Spotted Skipper<br />

Spotted Sedge-skipper<br />

Australian Admiral<br />

Yellow Admiral<br />

Common Imperial Blue Imperial Hairstreak<br />

Common Dusky-blue Varied Dusky-blue<br />

Further reading<br />

The Complete Field Guide to Butterflies of Australia by<br />

Michael F. Braby includes information on food plants of<br />

Australian Butterflies, although much is unknown.<br />

A coming article from Ian Faithfull will outline how much more<br />

needs to be known, <strong>and</strong> taken into account, in revegetation for<br />

butterflies, <strong>and</strong> the management of their habitat.<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

Book review<br />

The Biggest Estate on Earth<br />

— How Aborigines Made Australia<br />

Bill Gammage 2011<br />

Allen & Unwin, 384 pages<br />

Fire management in Victoria appears to<br />

be ruled by a science of idiocy. Burning<br />

of the l<strong>and</strong> is focused on reaching senseless<br />

area-targets with little regard to effects on<br />

ecology or even on reducing further fires. With<br />

all our science, technology <strong>and</strong> civilized ways, it<br />

seems that overall we are still a long way from<br />

appropriately managing <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing the<br />

country we live in, writes Karl Just<br />

The main theme of The Biggest Estate on Earth is that<br />

Aboriginal fire management was <strong>and</strong> still is an extremely<br />

complex science, involving an intimate underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

of ecological processes <strong>and</strong> plant-animal interactions,<br />

honed over many millennia. This book argues more than any<br />

before that many of the Australian l<strong>and</strong>scapes that the first<br />

Europeans encountered were almost totally an artefact of a<br />

complex management regime by humans. Consequently, as<br />

dispossession of the caretakers of country proceeded, so did<br />

the ecosystems they sustained for countless years begin to<br />

unravel. Whole l<strong>and</strong>scapes were to change rapidly beyond<br />

comprehension.<br />

This book draws on a massive amount of research (over<br />

1500 separate references), using excerpts from old journals,<br />

newspapers, paintings <strong>and</strong> photos. It then skillfully draws<br />

the evidence together to paint an eye-opening perspective<br />

of Australian ecology, describing just how aboriginal burning<br />

’made’ the l<strong>and</strong>. As the book proceeds you begin see the pre-<br />

1770 Australian continent as a managed estate of massive<br />

proportions. Gammage shows that aboriginal fire management<br />

didn’t involve merely setting the scrub on fire whenever it was<br />

deemed too thick; it was an intricate science. Balanced mosaics<br />

of open <strong>and</strong> treed vegetation were created to provide ideal<br />

habitat for particular fauna. The frequency <strong>and</strong> intensity of fire<br />

was often altered at a fine-scale to favour one plant species<br />

or community over another, while rainforest was in some parts<br />

of the country transformed into open grassy plains by lighting<br />

fires on hot summer days, using the right winds at the right time.<br />

Like many others, Gammage argues that with the use of fire,<br />

aboriginal peoples sculpted complex ecosystems, sustaining<br />

diverse communities of plants <strong>and</strong> animals.<br />

One of my favourite chapters is ‘Heaven on Earth’, where<br />

Gammage describes the inseparable nature of aboriginal<br />

theology <strong>and</strong> ecology. As Gammage writes, ‘ecology explains<br />

what happens, the Dreaming why it happens’. Here science<br />

<strong>and</strong> spirituality run on parallel spheres. An example is given<br />

of a group in northern Australia who took great care to avoid<br />

burning a jungle thicket, so conserving a restricted community<br />

<strong>and</strong> its dependant fauna. However this was not explained in<br />

conservation terms, but rather that if the area was burnt, the<br />

spirits of the place would blind them. Again, aboriginal women<br />

harvesting yams in the top end would always leave the top on<br />

the yam <strong>and</strong> cover it with earth. This allowed the yam to re-grow<br />

<strong>and</strong> provide more food later, but it was explained ‘if dig it all<br />

out, then that food spirit will get real angry <strong>and</strong> won’t let<br />

anymore yam grow in that place’. For aboriginal people<br />

there are deeper processes at work than just plain science;<br />

if the Dreaming is followed, the l<strong>and</strong> flourishes.<br />

Another great chapter is ‘Canvas of a Continent’. Here<br />

Gammage has reproduced a range of early paintings <strong>and</strong><br />

photographs, <strong>and</strong> for each one points out clues to fire patterns<br />

that can be seen in the various l<strong>and</strong>scapes. He has actually<br />

re-visited a lot of these sites to provide evidence of changes that<br />

have occurred since European invasion.<br />

‘A Capital Tour’ presents a wonderful tour of all of Australia’s<br />

capital cities, including descriptions from early explorers<br />

<strong>and</strong> colonists. One of the most fascinating of Gammage’s<br />

observations is that it was the shaping influence <strong>and</strong><br />

management of these areas by their traditional owners that led<br />

to them being selected as the sites worthy of our capital cities.<br />

Some of these future cites, such as Melbourne, Hobart <strong>and</strong><br />

Sydney, contained country described by colonists as resembling<br />

English ‘gentlemen’s parks’. These ‘parks’ were well maintained<br />

grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> grassy woodl<strong>and</strong>s, easy to walk through <strong>and</strong><br />

abounding with wildlife, which Gammage argues had been<br />

partly created <strong>and</strong> maintained by Aboriginal burning regimes.<br />

It is sadly ironic that many early settlers found the country so<br />

agreeable that they believed it had been prepared for them by<br />

the h<strong>and</strong> of God. Little did they know it had been significantly<br />

shaped by the very people they claimed did not manage the<br />

l<strong>and</strong> at all, leading to the to the Crown’s stamp of Terra Nullius<br />

(l<strong>and</strong> belonging to no one) across the continent.<br />

I must say that I did find the reading a bit frustrating at<br />

times. Gammage will occasionally jump all over the place<br />

when illustrating a point, listing numerous quotes from various<br />

times from places all over Australia. In his popular book,<br />

Victorian Bush, its Original <strong>and</strong> Natural Condition (Reviewed<br />

in <strong>Indigenotes</strong> 22:1), Ron Hateley argued the point that there<br />

has been a lot of assumptions made of Victorian aboriginal<br />

burning based on burning by aboriginal peoples from northern<br />

Australia, where the ecosystems <strong>and</strong> culture are significantly<br />

different. Gammage occasionally appears to make this same<br />

error, illustrating a point based on evidence from vastly different<br />

places. I was also sometimes worried with some of the content.<br />

Most of the work is backed up by frequent references, but<br />

then occasionally a rather bold statement is made without any<br />

reference or evidence. One example includes a discussion on<br />

Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans) forests, which he claims<br />

‘must have been’ regularly burnt at low intensity to reduce<br />

undertsorey cover. While I don’t think this out of the question,<br />

to my knowledge there is still very little evidence that aboriginal<br />

people managed this community with fire. There are also a few<br />

inaccurate statements, such as a claim that Kangaroos have<br />

vanished from Kangaroo Ground north-east of Melbourne (they<br />

were recently being culled due to high population numbers)<br />

<strong>and</strong> another describing how the Otway Ranges have shifted<br />

from a mosaic of heathl<strong>and</strong>s, woodl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> forests to climax<br />

rainforest. Anyone who has even driven through the Otways<br />

knows that climax rainforest is still of restricted occurrence,<br />

being largely confined to sheltered gullies.<br />

There is still wide controversy regarding to what extent<br />

aboriginal burning shaped Victorian l<strong>and</strong>scapes, with many<br />

believing that the ‘fire-stick farming’ concept has been greatly<br />

exaggerated. CONTINUED PAGE 11<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2 9

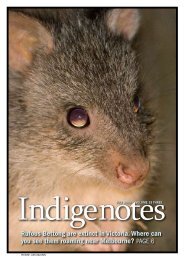

Little Penguin outing<br />

On the first Sunday night<br />

in April, IFFA visitors<br />

<strong>and</strong> Earthcare St Kilda<br />

volunteers gather at St Kilda<br />

Pier for<br />

the last of the fortnightly<br />

Little Penguin monitoring<br />

for this season.<br />

We are received by Zoe<br />

Hogg, who has been<br />

coordinating the research<br />

activities for the last 26 years. As<br />

we walk along the pier <strong>and</strong> pass<br />

the public boardwalk, she tells me<br />

about the enormous datasets she<br />

has obtained with the help of her<br />

many volunteers. This year,<br />

she has had PhD students<br />

run tests on the data with<br />

surprising results; Zoe<br />

estimated the St Kilda pier<br />

population to consist of<br />

around 1500 animals, but<br />

in-depth analysis showed<br />

a possible population of<br />

close to 3000.<br />

One of the reasons why<br />

the birds are doing well<br />

in this not very peaceful<br />

spot is their stress-resistant<br />

nature. As we walk along<br />

the pier in the dark, we<br />

can hear their social calls<br />

<strong>and</strong> see them scramble<br />

over the rocks, looking<br />

for their burrows. Even<br />

drunk Irish backpackers<br />

don’t deter them, which is<br />

a feat not many humans<br />

can boast of. Bravely they<br />

Male or female? Humans favour the beak<br />

measurement test. Flash-free: Mick Connolly<br />

waddle between the boulders, occasionally jumping from<br />

rock to rock, setting off squeals of laugher <strong>and</strong> excitement<br />

among the tourists. The only thing really harmful to them is<br />

a camera flash, one of the volunteers explains. “Their eyes are<br />

very photosensitive,” she tells me. “Being flashed in the face<br />

by a bright white light will blind them for such a long amount<br />

of time, they can’t find their burrows to feed their chicks. Red<br />

light, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, is safe to use as they can’t see the red<br />

light spectrum like we do.”<br />

As we leave the boardwalk <strong>and</strong> Zoe opens the padlock to the<br />

big fence on the breakwater, I can’t help but feel a bit sorry for<br />

the two patient volunteers that patrol the area <strong>and</strong> keep an eye<br />

on the tourists. “No flash please,” I can hear them say every<br />

few minutes, as they try to educate the visitors <strong>and</strong> protect the<br />

penguins from a light-overdose. If that were me, I don’t think I<br />

could be that patient for long. After the third warning I would<br />

most likely be ready to push people off the boardwalk into the<br />

water. I have great respect for their dedication.<br />

Beyond the fence all is quiet.<br />

The monitoring will take place in<br />

this restricted area of the pier. We<br />

split up in groups, each of which<br />

will sweep a part of the breakwater<br />

for penguins.<br />

“I have hidden 10 Easter eggs<br />

last night,” Zoe announces,<br />

“if you don’t find all of them,<br />

I’ll know you’re slacking it.”<br />

Grinning, she unpacks her<br />

backpack <strong>and</strong> gets her monitoring<br />

tools ready. It doesn’t take long<br />

for a volunteer to catch the first<br />

penguin. He is on his belly,<br />

sticking his arm as far down<br />

a burrow as he can manage.<br />

Squawking loudly in protest, the<br />

little penguin tries to wriggle itself<br />

out of his grasp as he pulls it out<br />

from between the rocks. When<br />

that doesn’t work, it resorts to<br />

a vicious pecking into the volunteer’s<br />

fingers. Watching the dagger-like beak<br />

tearing through the cloth, it is instantly<br />

clear to me why they are all wearing<br />

gloves. I used to wonder what would<br />

happen to the poor little things when<br />

somebody grabbed them, but my fears<br />

were unfounded; between the wriggling,<br />

screaming <strong>and</strong> pecking, they seem to be<br />

able to take care of themselvesl.<br />

The volunteer carefully drops the<br />

penguin head-first into a little cloth bag<br />

<strong>and</strong> Zoe weighs it with a h<strong>and</strong>-held<br />

scale. Around this time of year, they are<br />

supposed to weigh about 1.5 kilos. The<br />

penguin’s catch location is recorded, <strong>and</strong><br />

the width of its beak, which determines<br />

its sex (males have slightly broader<br />

beaks). All penguins are checked for<br />

PIT-tags, the little chips that are also<br />

used to tag dogs <strong>and</strong> cats, <strong>and</strong> the identification number is<br />

noted. This way, the researchers can follow the individual<br />

penguins throughout their lifetime.<br />

One volunteer catches two chicks in the same burrow. They<br />

look funny, with their dazed expressions <strong>and</strong> plucky down<br />

nesting feathers all over the place, like a bad haircut. Their<br />

parents have not returned from hunting yet, so we quickly<br />

weigh them <strong>and</strong> insert PIT-tags before putting them back into<br />

their burrow.<br />

“It’s a shame,” the volunteer tells me, “these chicks are<br />

probably not going to make it through the winter. It’s too late<br />

in the season, they should have already been self-sufficient<br />

by now.” I ask Zoe if this happens a lot. She shakes her head.<br />

“We’ve had a very good year for penguins,” she says, “because<br />

last year was terrible. There were very few nests. But this year,<br />

the penguins that did not have nests last year seemed to make<br />

up for it by having two nests this breeding season. They started<br />

breeding much earlier than usual.<br />

10<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC

These chicks probably come from a second nest <strong>and</strong> they<br />

won’t make it before the weather gets bad. But as their siblings<br />

are already out there, it shouldn’t matter for the population size.”<br />

It’s harsh for the two little ones, but that’s life.<br />

We catch plenty of penguins that night. One is a massive<br />

fatty, weighing a whopping 2.4 kilos. I learn that this one is<br />

about to moult. When moulting, the penguins change all<br />

of their feathers over in the space of 2-3 weeks. During that<br />

time they can’t go out into the water to hunt <strong>and</strong> stay in<br />

their burrows. So they stock up on energy <strong>and</strong> fat-reserves<br />

beforeh<strong>and</strong> to last them until their new water-resistant<br />

plumage is ready. All the newly moulted penguins we catch<br />

are beautiful. Their feathers are sleek <strong>and</strong> shiny, with the<br />

unmistakable metallic blue hue that this species is known<br />

for. By the time we are finished, our little group has a few<br />

dozen sightings under its belt (including penguins that were<br />

recorded as ‘audible’ <strong>and</strong> ‘unreachable’ when we could hear<br />

them but not get to them). We pack up <strong>and</strong> walk back to<br />

the gate. “Here, take these home,” Zoe says <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong>s out<br />

chocolate Easter eggs, some of which have suspicious peckmarks<br />

on them. “Good job, you’ve found them all.”<br />

Fam Charko<br />

Want to learn more about Little Penguins?<br />

Visit the webpage of Earthcare St Kilda:<br />

http://home.vicnet.net.au/~earthcar<br />

Book review CONTINUED FROM PAGE 9<br />

One Australasia-wide study recently released has even<br />

claimed that aboriginal burning had a negligible effect<br />

on Australia’s l<strong>and</strong>scapes, which is certainly at odds with<br />

the findings of many historians. The Biggest Estate on Earth is<br />

certainly a hefty body of evidence that should be considered<br />

by anyone involved in fire management. Whatever the case,<br />

Gammage’s work certainly doesn’t support current Victorian fire<br />

management, which is purely focused on ‘putting runs on the<br />

board’ — burning as much public l<strong>and</strong> as possible with little<br />

regard to the ecological attributes or fire hazard of the site.<br />

Despite some of the draw-backs I would still highly<br />

recommend this book to anyone interested in environmental<br />

management, particularly fire ecology. It is a remarkable<br />

synthesis of ecology <strong>and</strong> culture, bringing together an enormous<br />

range of natural themes into one fascinating book. For me<br />

it greatly reinforced the underst<strong>and</strong>ing that management of<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes with fire is a complex art, <strong>and</strong> that mismanagement<br />

can have drastic consequences. I hope that the book will<br />

contribute to raising this awareness in our community, where<br />

fire management is currently at the whim of politics <strong>and</strong> poor<br />

science.<br />

Gammage concludes the book with some grave but important<br />

insights:<br />

‘There is no return to 1788. Non aboriginals are too<br />

many, too centralized, too stratified, too comfortable,<br />

too conservative, too successful, too ignorant. We<br />

are still newcomers, still in wilderness, still exporting<br />

goods <strong>and</strong> importing people <strong>and</strong> values. We see<br />

extinctions, pollution, erosion, salinity, bushfire <strong>and</strong><br />

exotic pests <strong>and</strong> diseases, but argue over who should<br />

pay . . . If we are to survive, let alone feel at home, we<br />

must begin to underst<strong>and</strong> our country. If we succeed,<br />

one day we might become Australian.’<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

http://www.iffa.org.au<br />

Incorporated <strong>Association</strong> No: A0015723B<br />

Office Bearers<br />

President: Brian Bainbridge, 7 Jukes Rd Fawkner 3060 (03)<br />

9359 0290(ah) email: president@iffa.org.au<br />

Vice-President: Vanessa Craigie, email: vicepres@iffa.org.au<br />

94973730 (ah).<br />

Secretary: Michele Arundell PO Box 77, Kallista 3791.<br />

(03) 9755 3347 (ah) email: secretary@iffa.org.au<br />

Treasurer: Tania Sloan, 23 Harrison Street Brunswick East 3057,<br />

treasurer@iffa.org.au<br />

Public Officer: Peter Wlodarzyck, 0418 317 725<br />

email: publicofficer@iffa.org.au<br />

Events Coordinator: Fam Charko, activities@iffa.org.au<br />

0402 519 124<br />

Newsletter Editor: Tony Faithfull, (03) 9386 0264 (ah).<br />

21 Harrison St East Brunswick 3057. editor@iffa.org.au<br />

Webmaster: Vacant<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Nurseries Liaison Officer:<br />

Judy Allen, nurseries@iffa.org.au<br />

Student representative: Karen McGregor, student@iffa.org.au<br />

Fundraising Coordinator: vacant<br />

Ecological Information Coordinator:<br />

Karl Just, email: info@iffa.org.au<br />

Committee members: Liz Henry <strong>and</strong> Linda Bradburn<br />

Life member<br />

Patricia Crowley<br />

<strong>Indigenotes</strong> is the newsletter of the <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

The views expressed in <strong>Indigenotes</strong> are not necessarily those<br />

of the <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

Call for articles<br />

<strong>Indigenotes</strong> is a newsletter by IFFA members for IFFA members.<br />

Stories, snippets, photos <strong>and</strong> reports from members are always<br />

welcome.<br />

If it’s something you’re doing with flora or fauna or habitat, write it<br />

down <strong>and</strong> send it to IFFA’s editor at Membership<br />

$40 per annum for non-profit organizations,<br />

$50 per annum for corporations,<br />

$25 per annum for individuals, or $20 per annum concession,<br />

$35 per annum for families,<br />

$500 for individual life members or<br />

$700 for family life members.<br />

Membership includes<br />

4 issues of <strong>Indigenotes</strong> per year,<br />

•<br />

Occasional freebies or discounts<br />

Discount subscription to Ecological Management & Restoration<br />

Journal ($72, inc GST)<br />

Membership applications <strong>and</strong> renewals should be sent to<br />

21 Harrison St, Brunswick East, 3057<br />

Problems with membership renewals? Please contact<br />

Tony Faithfull on 93860264 or membership@iffa.org.au<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 23 NUMBER 2 11

Little Penguin chick <strong>and</strong> the h<strong>and</strong>s of an Earthcare volunteer on the breakwater at St Kilda pier.<br />

The photo is flash-free, lit by a single torch. The camera is a Canon 1D4, the ISO rating is 12,800.<br />

Story: page 10<br />

Contents<br />

IFFA excursion invitation; President’s letter 2-3 Book review 9, 11<br />

The forgotten flora 4 Little Penguin outing 10<br />

Natureshare5 Contact us 11<br />

Butterflies in the suburbs 6-8<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC