- Page 2: Introduction to Paleobiology and th

- Page 6: Introduction to Paleobiology and th

- Page 10: Contents Full contents Preface vii

- Page 16: viii FULL CONTENTS The tree of life

- Page 20: x FULL CONTENTS Rise of the mammals

- Page 24: xii PREFACE (Copenhagen), Mike Bass

- Page 28: 2 INTRODUCTION TO PALEOBIOLOGY AND

- Page 32: 4 INTRODUCTION TO PALEOBIOLOGY AND

- Page 36: 6 INTRODUCTION TO PALEOBIOLOGY AND

- Page 40: 8 INTRODUCTION TO PALEOBIOLOGY AND

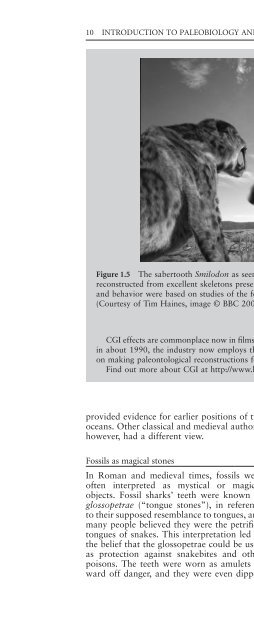

- Page 46: PALEONTOLOGY AS A SCIENCE 11 ·LAMI

- Page 50: PALEONTOLOGY AS A SCIENCE 13 debate

- Page 54: PALEONTOLOGY AS A SCIENCE 15 simple

- Page 58: PALEONTOLOGY AS A SCIENCE 17 Animal

- Page 62: PALEONTOLOGY AS A SCIENCE 19 (a) (b

- Page 66: PALEONTOLOGY AS A SCIENCE 21 Hammer

- Page 70: FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 23 The Ea

- Page 74: FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 25 tions

- Page 78: FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 27 strata

- Page 82: FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 29 Box 2.

- Page 86: FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 31 Sectio

- Page 90: FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 33 3 boun

- Page 94:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 35 Global

- Page 98:

(a) MRS SU MFS DS HST GS TST LST De

- Page 102:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 39 m 100

- Page 106:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 41 from o

- Page 110:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 43 may be

- Page 114:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 45 Box 2.

- Page 118:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 47 Kalaha

- Page 122:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 49 J J Cr

- Page 126:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 51 400 Nu

- Page 130:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 53 Trondh

- Page 134:

FOSSILS IN TIME AND SPACE 55 Review

- Page 138:

Chapter 3 Taphonomy and the quality

- Page 142:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 146:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 150:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 154:

peat TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF T

- Page 158:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 162:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 166:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 170:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 174:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 178:

TAPHONOMY AND THE QUALITY OF THE FO

- Page 182:

Chapter 4 Paleoecology and paleocli

- Page 186:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 81 e

- Page 190:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 83 0

- Page 194:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 85 B

- Page 198:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 87 l

- Page 202:

1 2 3 4 5 Herbivores Deposit feeder

- Page 206:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 91 (

- Page 210:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 93 c

- Page 214:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 95 B

- Page 218:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 97 B

- Page 222:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 99 (

- Page 226:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 101

- Page 230:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 103

- Page 234:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 105

- Page 238:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 107

- Page 242:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 109

- Page 246:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 111

- Page 250:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 113

- Page 254:

PALEOECOLOGY AND PALEOCLIMATES 115

- Page 258:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 262:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 266:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 270:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 274:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 278:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 282:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 286:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 290:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 294:

MACROEVOLUTION AND THE TREE OF LIFE

- Page 298:

Chapter 6 Fossil form and function

- Page 302:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 139 Box 6.

- Page 306:

(a) (b) 1 cm Figure 6.2 Sexual dimo

- Page 310:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 143 Box 6.

- Page 314:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 145 passes

- Page 318:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 147 Late S

- Page 322:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 149 Stylop

- Page 326:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 151 the bo

- Page 330:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 153 0 Wind

- Page 334:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 155 the kn

- Page 338:

{ FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 157 stan

- Page 342:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 159 (a) (b

- Page 346:

FOSSIL FORM AND FUNCTION 161 Shubin

- Page 350:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 354:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 358:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 362:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 366:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 370:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 374:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 378:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 382:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 386:

MASS EXTINCTIONS AND BIODIVERSITY L

- Page 390:

Chapter 8 The origin of life Key po

- Page 394:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 185 membrane pri

- Page 398:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 187 protocell re

- Page 402:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 189 then from th

- Page 406:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 191 Bacteria Arc

- Page 410:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 193 Brasier and

- Page 414:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 195 (a) (b) Figu

- Page 418:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 197 (Fig. 8.11a)

- Page 422:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 199 Nucleus (n)

- Page 426:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 201 250 μm 25

- Page 430:

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE 203 Ciccarelli,

- Page 434:

PROTISTS 205 The world of microbes

- Page 438:

Ichthyospores PROTISTS 207 Plantae

- Page 442:

PROTISTS 209 Foraminifera Foraminif

- Page 446:

PROTISTS 211 spectrum of shapes, fr

- Page 450:

1.1 1.3 1.1 PROTISTS 213 Box 9.3 Mo

- Page 454:

PROTISTS 215 Allogromia R freshwate

- Page 458:

PROTISTS 217 Box 9.5 Classification

- Page 462:

Figure 9.11 Haeckel’s radiolarian

- Page 466:

PROTISTS 221 Netromorphs • Elonga

- Page 470:

PROTISTS 223 epitheca apex or anter

- Page 474:

PROTISTS 225 (c) (a) (b) (d) (e) (f

- Page 478:

PROTISTS 227 Box 9.10 Atomic force

- Page 482:

PROTISTS 229 epicingulum hypocingul

- Page 486:

PROTISTS 231 aperture recessed oper

- Page 490:

PROTISTS 233 tively late in the geo

- Page 494:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 235 ORIGINS

- Page 498:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 237 suggest

- Page 502:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 239 Neoprot

- Page 506:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 241 and res

- Page 510:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 243 Ma 500

- Page 514:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 245 Ediacar

- Page 518:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 247 Figure

- Page 522:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 249 walled

- Page 526:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 251 METAZOA

- Page 530:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 253 Recent

- Page 534:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 255 Box 10.

- Page 538:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 257 The rib

- Page 542:

ORIGIN OF THE METAZOANS 259 Ordovic

- Page 546:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 550:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 554:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 558:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 562:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 566:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 570:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 574:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 578:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 582:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 586:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 590:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 594:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 598:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 602:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 606:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 610:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 614:

THE BASAL METAZOANS: SPONGES AND CO

- Page 618:

Chapter 12 Spiralians 1: lophophora

- Page 622:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 299 lin

- Page 626:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 301 cha

- Page 630:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 303 PAL

- Page 634:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 305 “

- Page 638:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 307 (a)

- Page 642:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 309 num

- Page 646:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 311 Lin

- Page 650:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 313 the

- Page 654:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 315 lop

- Page 658:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 317 Box

- Page 662:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 319 Pal

- Page 666:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 321 0.0

- Page 670:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 323 Loc

- Page 674:

SPIRALIANS 1: LOPHOPHORATES 325 Eas

- Page 678:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 327 This fam

- Page 682:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 329 Class SC

- Page 686:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 331 Box 13.3

- Page 690:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 333 expansio

- Page 694:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 335 cardinal

- Page 698:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 337 prismato

- Page 702:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 339 Seawater

- Page 706:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 341 penis ma

- Page 710:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 343 (a) (b)

- Page 714:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 345 siphuncl

- Page 718:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 347 dorsal i

- Page 722:

(a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g) (h) (i)

- Page 726:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 351 Box 13.7

- Page 730:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 353 ally arr

- Page 734:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 355 shelf po

- Page 738:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 357 shell ap

- Page 742:

SPIRALIANS 2: MOLLUSKS 359 to recov

- Page 746:

Chapter 14 Ecdysozoa: arthropods Ke

- Page 750:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 363 Box 14.1

- Page 754:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 365 (a) (b) (

- Page 758:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 367 doublure.

- Page 762:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 369 protaspid

- Page 766:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 371 (a) (b) (

- Page 770:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 373 pelagic f

- Page 774:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 375 FAW PGW O

- Page 778:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 377 (a) (b) (

- Page 782:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 379 Box 14.5

- Page 786:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 381 Number of

- Page 790:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 383 (b) (a) (

- Page 794:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 385 Articulat

- Page 798:

ECDYSOZOA: ARTHROPODS 387 The Late

- Page 802:

Chapter 15 Deuterostomes: echinoder

- Page 806:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 810:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 814:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 818:

(a) (b) (d) (c) (e) Figure 15.5 Som

- Page 822:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 826:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 830:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 834:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 838:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 842:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 846:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 850:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 854:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 858:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 862:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 866:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 870:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 874:

DEUTEROSTOMES: ECHINODERMS AND HEMI

- Page 878:

Chapter 16 Fishes and basal tetrapo

- Page 882:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 429 grow

- Page 886:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 431 Box

- Page 890:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 433 (c)

- Page 894:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 435 Solv

- Page 898:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 437 Numb

- Page 902:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 439 Box

- Page 906:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 441 Box

- Page 910:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 443 eart

- Page 914:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 445 250

- Page 918:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 447 Quat

- Page 922:

large orbit (a) 5 mm (b) 20 mm toot

- Page 926:

FISHES AND BASAL TETRAPODS 451 Dino

- Page 930:

Chapter 17 Dinosaurs and mammals Ke

- Page 934:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 455 (a) (c) (

- Page 938:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 457 (a) (b) F

- Page 942:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 459 (a) 30,00

- Page 946:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 461 Box 17.2

- Page 950:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 463 Box 17.3

- Page 954:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 465 Box 17.5

- Page 958:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 467 Box 17.6

- Page 962:

elongate humerus fused radius and u

- Page 966:

names Archonta and Glires, and it m

- Page 970:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 473 Gorillas,

- Page 974:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 475 50 mm (a)

- Page 978:

DINOSAURS AND MAMMALS 477 Neanderta

- Page 982:

Chapter 18 Fossil plants Key points

- Page 986:

FOSSIL PLANTS 481 (a) (c) 0.1 mm ca

- Page 990:

FOSSIL PLANTS 483 Figure 18.3 Sporo

- Page 994:

FOSSIL PLANTS 485 Box 18.2 Classifi

- Page 998:

FOSSIL PLANTS 487 spores 2n 2n n n

- Page 1002:

FOSSIL PLANTS 489 The giant lycopsi

- Page 1006:

FOSSIL PLANTS 491 Lepidostrobophyll

- Page 1010:

FOSSIL PLANTS 493 warmth. Hence see

- Page 1014:

FOSSIL PLANTS 495 Botanical classif

- Page 1018:

FOSSIL PLANTS 497 (a) (b) (c) (d) (

- Page 1022:

FOSSIL PLANTS 499 Box 18.5 Reconstr

- Page 1026:

FOSSIL PLANTS 501 (a) (c) (b) top o

- Page 1030:

FOSSIL PLANTS 503 living gnetalean

- Page 1034:

FOSSIL PLANTS 505 40 Number of angi

- Page 1038:

FOSSIL PLANTS 507 ture change in No

- Page 1042:

Chapter 19 Trace fossils Key points

- Page 1046:

TRACE FOSSILS 511 Box 19.1 Jumping

- Page 1050:

TRACE FOSSILS 513 (a) (c) (a) (b) (

- Page 1054:

TRACE FOSSILS 515 (a) (b) (c) (d) p

- Page 1058:

TRACE FOSSILS 517 Figure 19.8 Trace

- Page 1062:

TRACE FOSSILS 519 1 2 3 (a) 4 Figur

- Page 1066:

TRACE FOSSILS 521 FL SL SL FL Figur

- Page 1070:

TRACE FOSSILS 523 Box 19.6 The nine

- Page 1074:

TRACE FOSSILS 525 3 2 2 3 4 5 1 2 3

- Page 1078:

TRACE FOSSILS 527 and traces are lo

- Page 1082:

TRACE FOSSILS 529 There is rare evi

- Page 1086:

TRACE FOSSILS 531 • Colonization

- Page 1090:

Chapter 20 Diversification of life

- Page 1094:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 535 Box 20.

- Page 1098:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 537 because

- Page 1102:

CAMBRIAN FAUNA 1. Trilobita 2. Inar

- Page 1106:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 541 models

- Page 1110:

Time (Ma) 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

- Page 1114:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 545 major s

- Page 1118:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 547 Time (M

- Page 1122:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 549 communi

- Page 1126:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 551 sized p

- Page 1130:

DIVERSIFICATION OF LIFE 553 Maynard

- Page 1134:

GLOSSARY 555 analog a feature of tw

- Page 1138:

GLOSSARY 557 cellulose a carbohydra

- Page 1142:

GLOSSARY 559 dibranchiate “two-ar

- Page 1146:

GLOSSARY 561 biomass of primary pro

- Page 1150:

GLOSSARY 563 intelligent design (ID

- Page 1154:

GLOSSARY 565 teeth, cheek teeth, in

- Page 1158:

GLOSSARY 567 peristome “around mo

- Page 1162:

GLOSSARY 569 rhizome “root”; an

- Page 1166:

GLOSSARY 571 taxon a group of organ

- Page 1170:

Appendix 1 Stratigraphic chart

- Page 1174:

Appendix 2 Paleogeographic maps 30

- Page 1178:

apomorphies 130, 132 Appalachian-Ca

- Page 1182:

evolution 357 life attitude 352, 35

- Page 1186:

iotic replacements 545-6 competitiv

- Page 1190:

fossil assemblages 26 associations

- Page 1194:

Late Cambrian extinction event 178

- Page 1198:

“great oxygenation event” 189-9

- Page 1202:

classification 211, 214, 217 evolut

- Page 1206:

swimming structures 130 symbiosis 9