Download - Goodman Theatre

Download - Goodman Theatre

Download - Goodman Theatre

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

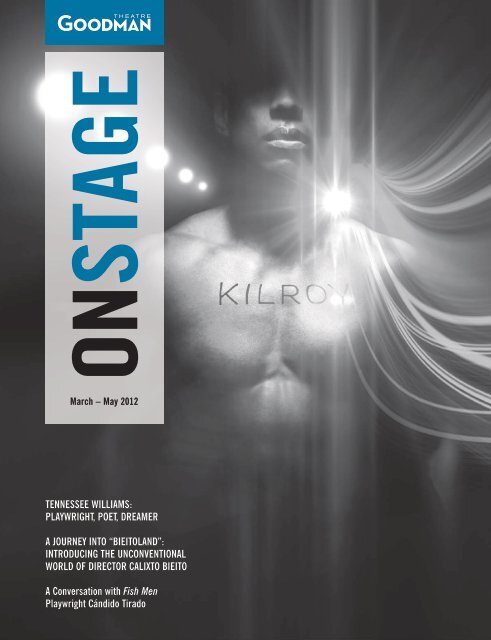

March – May 2012<br />

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS:<br />

PLAYWRIGHT, POET, DREAMER<br />

A JOURNEY INTO “BIEITOLAND”:<br />

INTRODUCING THE UNCONVENTIONAL<br />

WORLD OF DIRECTOR CALIXTO BIEITO<br />

A Conversation with Fish Men<br />

Playwright Cándido Tirado

March – May 2012<br />

CONTENTS<br />

In the Albert<br />

1 Why Camino Real?<br />

2 Tennessee Williams: Playwright, Poet, Dreamer<br />

7 Tennessee in Chicago<br />

8 A Journey into “Bieitoland”: Introducing the Unconventional World<br />

of Director Calixto Bieito<br />

In the Owen<br />

12 A Conversation with Cándido Tirado<br />

15 For Love or Money: The World of Chess Hustling<br />

At the <strong>Goodman</strong><br />

16 Insider Access Series<br />

In the Wings<br />

17 Imparting Culture and Communication: A Conversation with Ira Abrams<br />

Scene at the <strong>Goodman</strong><br />

19 Race Opening Night<br />

Celebrating Race and Diversity<br />

Off Stage<br />

20 A Legacy of Great Theater<br />

For Subscribers<br />

21 Calendar<br />

VOLUME 27 #3<br />

Co-Editors | Lesley Gibson, Lori Kleinerman,<br />

Tanya Palmer<br />

Graphic Designer | Tyler Engman<br />

Production Manager | Lesley Gibson<br />

Contributing Writers/Editors | Neena<br />

Arndt, Jeff Ciaramita, Jeffrey Fauver, Lisa<br />

Feingold, Katie Frient, Lesley Gibson, Lori<br />

Kleinerman, Caitlin Kunkel, Dorlisa Martin,<br />

Julie Massey, Tanya Palmer, Teresa Rende,<br />

Victoria Rodriguez, Denise Schneider, Steve<br />

Scott, Jenny Seidelman, Willa J. Taylor,<br />

Kate Welham.<br />

OnStage is published in conjunction with<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> productions. It is<br />

designed to serve as an information source<br />

for <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> Subscribers. For ticket<br />

and subscription information call<br />

312.443.3810. Cover: Image design and<br />

direction by Kelly Rickert.<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> productions are made possible<br />

in part by the National Endowment for the<br />

Arts; the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency;<br />

and a CityArts grant from the City of<br />

Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and<br />

Special Events; and the Leading National<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong>s Program, a joint initiative of the<br />

Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the<br />

Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.<br />

Written comments and<br />

inquiries should be sent to:<br />

The Editor, OnStage<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

170 North Dearborn Street<br />

Chicago, IL 60601<br />

or email us at:<br />

OnStage@<strong>Goodman</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>.org

IN THE ALBERT<br />

FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR<br />

Photo by Brian Kuhlmann.<br />

Why Camino Real?<br />

During my tenure as artistic director I have had the privilege of bringing some of the most notable directors now working<br />

on the world stage to the <strong>Goodman</strong>, including Peter Sellars, JoAnne Akalaitis, Ivo van Hove, Elizabeth LeCompte,<br />

Flora Lauten (from the esteemed Cuban company Teatro Buendía) and our own Mary Zimmerman. Although vastly<br />

different in style and approach, these directors share a passion for exploring new ways of theatrical storytelling, an<br />

uncompromising singularity of vision and a radical (and often controversial) way of reimagining classical texts. To this<br />

group I am extremely proud to add Calixto Bieito, a Barcelona-based director whose soaring, radical interpretations<br />

of everything from classic operas to Shakespeare have astonished, inflamed and challenged audiences throughout<br />

Europe and South America.<br />

My first experience with Calixto’s work came in 2004, with his sexually charged interpretation of Mozart’s The<br />

Abduction from the Seraglio in Berlin. I found that production to be both fascinating and disturbing; Calixto’s investigation<br />

of the dark subtext that lay beneath the “classical” exterior of the piece displayed a courage and sophistication<br />

that was, to me, profound and unsettling. Soon after the performance I met with him, and was immediately<br />

impressed by his warmth, intelligence and infectious passion for his work. When we began to discuss possible<br />

projects that might be of interest to him, he revealed his love for the works of one of my favorite writers, Tennessee<br />

Williams. Though our conversation began with a discussion of Williams’ better-known works, in talking to Calixto<br />

it occurred to me that his bold artistry might be better used to explore one of Williams’ less often performed plays,<br />

Camino Real. First produced in 1953, Camino remains one of the author’s most poetic works, and one of his most<br />

ambitious: it is an impressionistic musing on the nature of love, loss, humanity and the encroachment of time,<br />

peopled largely by iconic figures of romance who are coming to terms with their own mortality. Because of its nonrealistic<br />

milieu and aching lyricism, I felt that this seldom-produced work, long considered one of Williams’ most<br />

personal, would inspire Calixto to do what he does best: to create a world in which the playwright’s images and ideas<br />

could take flight and soar. After reading the play, Calixto agreed, and the result is a full-bodied, extraordinarily theatrical<br />

piece which fuses Williams’ poetry, music and evocative imagery to create, in Williams’ words, “the continually<br />

dissolving and transforming images of a dream.”<br />

Although Camino Real is notably based less in realism than its author’s more familiar works, it shares with those<br />

plays a highly charged blend of disparate elements: beauty and brutality; moments of romance punctuated by shocking<br />

dissolution. As interpreted by one of today’s most courageous and uncompromising directors, I guarantee that its<br />

vivid images and haunting, sometimes squalid beauty will live with you for a long, long time.<br />

Robert Falls<br />

Artistic Director<br />

1

IN THE ALBERT<br />

2

Tennessee Williams:<br />

Playwright, Poet, Dreamer<br />

By Neena Arndt<br />

Tennessee Williams,<br />

circa 1955. Photo by<br />

FPG/Archive Photos/<br />

Getty Images.<br />

In the foreword to his phantasmagoric<br />

1953 allegory, Camino Real, playwright<br />

Tennessee Williams, who by then had<br />

made a name for himself with psychological<br />

dramas like A Streetcar Named Desire<br />

and The Glass Menagerie, wrote, “More<br />

than any other work I have done, this<br />

play has seemed to me like a construction<br />

of another world, a separate existence.”<br />

Casual Williams fans may remain<br />

unfamiliar with the dreamlike Camino<br />

Real, which differs stylistically from his<br />

better-known works. In fact, those who<br />

know only Williams’ “greatest hits” might<br />

be hard-pressed to believe that Camino<br />

Real—broad in scope and sweepingly<br />

ambitious—flowed from the same pen<br />

as the classics they cherish. But Camino<br />

Real springs from the deepest recesses of<br />

Williams’ heart and psyche, and offers a<br />

glimpse into the staggering imagination of<br />

this multifaceted writer.<br />

In 1951, two years before Camino Real<br />

premiered, Tennessee Williams became<br />

a household name when 27-year-old<br />

Marlon Brando swaggered and shouted<br />

his way to immortality as Stanley<br />

Kowalski in the film A Streetcar Named<br />

Desire. Under the direction of Elia<br />

Kazan, Brando portrayed Williams’ most<br />

iconic male character as lustful and sensuous,<br />

giving a grandiose performance<br />

that nonetheless was grounded in the<br />

realistic acting style of which Brando<br />

was a master. An early “method” actor,<br />

Brando was steeped in the theories of<br />

visionary Russian director Konstantin<br />

Stanislavsky, which permeated American<br />

theater and film in the mid-twentieth<br />

century. This style supplanted melodrama,<br />

which saw its heyday in the nineteenth<br />

century and took its last fluttery<br />

breaths in the middle of the twentieth,<br />

when writers like Tennessee Williams,<br />

Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller transformed<br />

the American stage with such<br />

masterworks as Streetcar, Long Day’s<br />

Journey into Night and Death of a<br />

Salesman. Directly imitating real life had<br />

never been among melodrama’s goals,<br />

but now, both on stage and on screen,<br />

many artists aimed to hold up a mirror<br />

to the world around them.<br />

Today, Tennessee Williams is most often<br />

remembered as one of the writers who<br />

pioneered this style in America. Indeed,<br />

the works for which he is best known use<br />

largely realistic plots and characters to<br />

achieve Williams’ goal of rooting around<br />

the human psyche. Their stories concern<br />

SYNOPSIS<br />

Tennessee Williams’ hauntingly poetic<br />

allegory takes us to a surreal, deadend<br />

town occupied by a colorful collection<br />

of lost souls anxious to escape<br />

but terrified of the unknown wasteland<br />

lurking beyond the city’s walls. When<br />

Kilroy, an American traveler and former<br />

boxer, inadvertently lands in this<br />

netherworld, he sets off on a fantastical<br />

adventure through illusion and<br />

temptation in an attempt to flee its<br />

confines—and defy his grim destiny.<br />

3

IN THE ALBERT<br />

“More than any other work I have<br />

done, this play has seemed to me like<br />

a construction of another world,<br />

a separate existence.”<br />

—Tennessee Williams<br />

events that could occur in the real world,<br />

and their characters confront their problems<br />

in psychologically realistic ways. Yet,<br />

even in these works, Williams’ language<br />

is languidly poetic, and his stage directions<br />

often indicate that he envisioned his<br />

works being performed with an undercurrent<br />

of visual and auditory metaphors. In<br />

A Streetcar Named Desire, for example,<br />

Williams indicates that Blanche’s descent<br />

into madness is underscored by echoing<br />

voices and “jungle noises.” If, in the text<br />

of Streetcar, Williams is holding a mirror<br />

up to life, it is a warped mirror, each distortion<br />

meticulously sculpted. The poetic<br />

elements in these works afford readers a<br />

glimpse of his wide-ranging sensibilities.<br />

But in order to fully appreciate the vastness<br />

of Williams’ dramatic imagination,<br />

one has to experience his more overtly<br />

surrealistic works like Camino Real, The<br />

Gnädiges Fräulein or Stairs to the Roof .<br />

In The Gnädiges Fräulein, a pair of southern<br />

ladies chatter and preen in rocking<br />

chairs while being entertained by a retired<br />

vaudeville performer who has had her<br />

eyes pecked out by an oversized bird. In<br />

Stairs to the Roof, the characters go on a<br />

whirlwind surreal journey before ascending<br />

symbolic stairs to the roof of an office.<br />

Here, the mirror Williams uses is straight<br />

out of a fun house—and like those twisted<br />

images that confront us at carnivals,<br />

they provide a different, but equally valid,<br />

way of perceiving and making sense of<br />

the world.<br />

The phrase “camino real” translates from<br />

Spanish as “royal road,” but in Williams’<br />

play it ironically represents a dead end.<br />

Camino Real places familiar characters<br />

from literature—such as Don Quixote,<br />

Casanova and Lord Byron—in a mythical<br />

town in an unspecified Latin American<br />

country where the “spring of humanity<br />

has gone dry.” Although the play contains<br />

references that place it in the twentieth<br />

century—an airplane, for example—the<br />

play’s time period remains fluid and<br />

ambiguous. The presence of literary<br />

characters from different eras reinforces<br />

the notion that the action occurs either in<br />

many time periods simultaneously, or in<br />

no time period in particular. These literary<br />

characters are joined by characters<br />

who are products of Williams’ imagination,<br />

such as an enigmatic gypsy and a<br />

freaky faction of “streetcleaners” whose<br />

job is to remove corpses from the streets.<br />

Much of the action centers around Kilroy,<br />

a newly arrived American whose name is<br />

inspired by the popular World War II era<br />

graffiti phrase “Kilroy was here.” A prizefighter<br />

with a “heart as big as a baby’s<br />

head,” Kilroy first appears to be the all-<br />

American hero—but the nightmare dreamscape<br />

in which he now finds himself<br />

proves more treacherous than any fighting<br />

ring. While Kilroy and his fellow inhabitants<br />

of the town are theoretically free to<br />

leave, outgoing transportation is sporadic<br />

and a vast desert wasteland stretches to<br />

the horizon—so setting out on foot seems<br />

foolhardy. Most of the characters remain<br />

stuck in their current situations, both<br />

geographically and emotionally, allowing<br />

Williams to explore the inner workings of<br />

their desperation, and their love for (or<br />

perhaps just attachment to) each other.<br />

4

OPPOSITE: Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando in A<br />

Streetcar Named Desire. ©Bettman/CORBIS. BOTTOM:<br />

Denholm Elliot and Elizabeth Seal in a scene from<br />

the Tennessee Williams’ play Camino Real. Photo by<br />

Popperfoto/Getty Images.<br />

Just as they occupy the town, the characters<br />

also inhabit the fertile landscape<br />

of Tennessee Williams’ mind, representing<br />

his experience of the world rather<br />

than the world’s literal outward appearance.<br />

Prior to Camino Real’s Broadway<br />

opening in 1953, Williams published an<br />

essay in The New York Times describing<br />

his thought processes about the play:<br />

My desire was to give audiences my<br />

own sense of something wild and<br />

unrestricted that ran like water in the<br />

mountains, or clouds changing shape<br />

in a gale, or the continually dissolving<br />

and transforming images of a dream.<br />

This sort of freedom is not chaos nor<br />

anarchy. On the contrary, it is the result<br />

of painstaking design, and in this work<br />

I have given more conscious attention<br />

to form and construction than I have<br />

in any work before. Freedom is not<br />

achieved simply by working freely.<br />

in 1953, theatergoers scratched their<br />

heads over Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for<br />

Godot, another play which places little<br />

focus on plot—but is now considered<br />

a staple of the Western canon.) Critic<br />

William Hawkins noted, “The first thing<br />

evident about this brave new play of<br />

Tennessee Williams is that explanations<br />

of it that suit you may not suit anybody<br />

else. The playwright has composed his<br />

work in terms of pure emotions. They<br />

are abstract, without excuse or motivation.<br />

What you see and hear is the effect<br />

on the heart, of human nature when it<br />

is greedy or hilarious or sorry for itself.”<br />

For other critics, the play inspired less<br />

openmindedness: John McClain opined,<br />

“There is not the slightest doubt that Mr.<br />

Williams has some provocative and highflown<br />

thoughts about love and life, and<br />

he is capable of lyrical and humorous<br />

and sometimes utterly earthy writing, but<br />

it seems to me that in this instance he<br />

knocked himself out being oblique.”<br />

Never inclined to scorn or ignore his<br />

audiences’ reactions to his plays,<br />

Williams returned to the typewriter<br />

after the play opened on Broadway and<br />

revised the script. The published version<br />

reflects the changes he made to help<br />

audiences enter his admittedly mysterious<br />

world—an added prologue which<br />

sets up the action, and some additional<br />

When the play premiered on Broadway<br />

in a lavish production by Elia Kazan,<br />

some critics and audiences applauded its<br />

stylistic originality, while others decried<br />

its lack of storyline and expressed confusion<br />

regarding Williams’ intentions. (Also<br />

WOMEN’S BOARD<br />

SPONSORS CAMINO REAL<br />

The <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> Women’s Board continues<br />

a long tradition of support for exciting and challenging<br />

work with its sponsorship of Camino<br />

Real. Since its formation in 1978, the Women’s<br />

Board has made it part of its mission to sponsor<br />

a production every season and provide<br />

crucial funding for the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s Education and<br />

Community Engagement programs.<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> gratefully salutes the Women’s<br />

Board as a Major Production Sponsor of Camino<br />

Real, and is extremely thankful for the dedication<br />

and generosity of its members.<br />

5

IN THE ALBERT<br />

scenes. Williams was also careful to<br />

note, in an afterword, that due to its reliance<br />

on visual elements, this particular<br />

play would provide a far more satisfying<br />

experience on the stage than on<br />

the page. While he acknowledged that<br />

some plays are “meant for reading,” he<br />

emphasized that text is not always of<br />

primary importance to a play:<br />

Of all the works I have written, this<br />

one was meant most for the vulgarity<br />

of performance. The printed script of a<br />

play is hardly more than an architect’s<br />

blueprint of a house not yet built or<br />

built and destroyed. The color, the<br />

grace and levitation, the structural<br />

pattern in motion, the quick interplay<br />

of live beings, suspended like fitful<br />

lightning in a cloud, these things are<br />

the play, not words on paper, nor<br />

thoughts and ideas of an author, those<br />

shabby things snatched off basement<br />

counters at Gimbel’s.<br />

In the years following, the revised play<br />

went on to numerous regional productions<br />

(including one at the <strong>Goodman</strong> in<br />

1958), usually receiving mixed reviews.<br />

In 1970 it was revived in New York by<br />

the Lincoln Center Repertory Company,<br />

and critic Clive Barnes proclaimed,<br />

“There are people who think that Camino<br />

Real is Tennessee Williams’ best play,<br />

and I believe that they are right. It is a<br />

play torn out of a human soul.” Barnes<br />

went on to observe that when the play<br />

was first produced in 1953, “there were<br />

many who found it obscure. Our standards<br />

of obscurity, like our standards of<br />

obscenity, have escalated since those<br />

dark days of theatrical innocence.” When<br />

Barnes wrote those words, only 17<br />

years had passed since Camino Real’s<br />

premiere—now, we experience Williams’<br />

work at a distance of nearly 60 years. In<br />

the interim, innovative playwrights like<br />

Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Eugene<br />

Ionesco and countless others have<br />

“The playwright has composed his work<br />

in terms of pure emotions. They are<br />

abstract, without excuse or motivation.<br />

What you see and hear is the effect on<br />

the heart, of human nature when it is<br />

greedy or hilarious or sorry for itself.”<br />

—William Hawkins, Critic<br />

spurred audiences to expand their ideas<br />

of what constitutes a play. These writers<br />

employ techniques such as extensive<br />

use of symbolism and placing their plays<br />

in no particular place or time. Viewed<br />

through the lens of history, Camino Real<br />

seems less radical than it did in 1953—<br />

though it remains a vivid, visceral peek<br />

into the mind of one of America’s most<br />

complex and beloved playwrights.<br />

BOTTOM: Mundy Spears and Emily Webbe in The Gnädiges<br />

Fräulein performed as part of WSC Avant Bard’s 2011<br />

Tennessee Continuum. Photo C. Stanley Photography.<br />

HONORING A LEGACY:<br />

HOPE ABELSON AND<br />

CAMINO REAL<br />

Through its 2011/2012 production of Camino<br />

Real, <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> honors the legacy of a<br />

true luminary of the Chicago arts world, the late<br />

Hope Abelson. At the <strong>Goodman</strong>—as well as<br />

many if not all theaters in Chicago—Hope was<br />

a champion of new work.<br />

Hope began her life in the arts as a performer,<br />

working as an actress in radio drama. Her<br />

career led her to serve as a producer for several<br />

Broadway shows. She also founded the American<br />

Friends of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival and<br />

she was instrumental in the early days of the<br />

League of Chicago <strong>Theatre</strong>s.<br />

In 1953, Hope served as an assistant on the<br />

original production of Camino Real. She was<br />

responsible for daily script changes and she made<br />

herself indispensable to both Tennessee Williams<br />

and the play’s director, Elia Kazan. She became a<br />

critical supporter of arts organizations large and<br />

small, including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra,<br />

Ravinia Festival, Court <strong>Theatre</strong>, Victory Gardens<br />

Theater and Steppenwolf <strong>Theatre</strong> Company. Hope<br />

was an early board member of the <strong>Goodman</strong> and<br />

also served on the Illinois Arts Council.<br />

The <strong>Goodman</strong> is grateful to her daughter Katherine<br />

Abelson, a <strong>Goodman</strong> Women’s Board member,<br />

and Katherine’s husband Robert J. Cornell, for<br />

carrying on this tradition through their support<br />

of our education and community engagement<br />

programs for Camino Real.<br />

Hope Abelson and her daughter Katherine at the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s Inaugural Gala.<br />

6

LEFT: Peg Murray and<br />

Scott Jaeck in <strong>Goodman</strong><br />

<strong>Theatre</strong>’s 1982 production<br />

of Tennessee<br />

Williams’ A House Not<br />

Meant to Stand. Photo<br />

by Lisa Ebright. BELOW:<br />

Tennessee Williams<br />

and <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

Executive Director Roche<br />

Schulfer outside the<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> Studio.<br />

Tennessee and Chicago<br />

By Steve Scott<br />

Although the city most often associated<br />

with Tennessee Williams’ work was New<br />

Orleans (his adopted home and the setting<br />

of some of his most famous works), it was<br />

Chicago that gave him his first real success<br />

in the theater and that would provide<br />

artistic haven to him late in his career.<br />

Williams’ love affair with the Windy City<br />

began in 1944 with the landmark success<br />

of The Glass Menagerie, produced<br />

at the Civic <strong>Theatre</strong> prior to its arrival on<br />

Broadway. Claudia Cassidy, the venerated<br />

critic for the Chicago Tribune, became a<br />

passionate advocate for the play, writing<br />

in her initial review that, “it reaches out<br />

its tentacles, first tentative, then gripping,<br />

and you are caught in its spell.” Cassidy’s<br />

praise, and her continued exhortations<br />

to local audiences to support the play,<br />

brought national attention to the work<br />

before it had even moved to New York,<br />

and helped establish Williams as the preeminent<br />

dramatist of his generation.<br />

Thereafter, Williams considered Chicago<br />

to be one of the best theater towns in<br />

the world; in a 1951 letter to Cassidy,<br />

he urged her to stump for the establishment<br />

of a strong locally based theater<br />

community here, exclaiming, “No better<br />

place on Earth!” Touring productions<br />

of his Broadway hits were a staple in<br />

Chicago in the 1950s and 1960s, and,<br />

as local producing companies began to<br />

sprout, Williams’ plays were an important<br />

part of their repertoire. Director<br />

George Keathley’s first major hit at the<br />

old Ivanhoe <strong>Theatre</strong> was a much-lauded<br />

revival of The Rose Tattoo which swept<br />

the first annual Joseph Jefferson Awards<br />

in 1969. Two years later, Keathley produced<br />

the world premiere of Williams’<br />

Out Cry, an experience unfortunately<br />

marred by the playwright’s erratic behavior—although<br />

Williams later admitted,<br />

after the failure of a subsequent New<br />

York production with a different director,<br />

that the play “was better in Chicago.”<br />

Problems also plagued the 1980 premiere<br />

of Clothes for a Summer Hotel, which<br />

starred <strong>Goodman</strong> School of Drama alumna<br />

Geraldine Page as the ill-fated Zelda<br />

Fitzgerald; although Williams himself was<br />

in better emotional shape, his play was<br />

greeted with critical disappointment.<br />

Later that year, the playwright embarked<br />

on an alliance with <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

that would result in in his final major<br />

work for the stage. Some Problems for<br />

the Moose Lodge, which was produced<br />

first in the <strong>Goodman</strong> Studio as one of<br />

three short plays collectively billed as<br />

Tennessee Laughs<br />

(a title Williams<br />

apparently loathed),<br />

was a darkly savage<br />

comedy detailing<br />

the travails of<br />

Cornelius and Bella<br />

McCorkle, an elderly<br />

couple dealing with<br />

the disintegration<br />

of their family and<br />

their marriage. The<br />

reception of Moose<br />

Lodge was positive<br />

enough to encourage<br />

Williams to expand the play into a longer<br />

one-act, now entitled A House Not Meant<br />

to Stand, produced in 1981, again in the<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> Studio. Despite some critical<br />

misgivings, Williams kept working on the<br />

play, encouraged by then-Artistic Director<br />

Gregory Mosher; the result was a fulllength<br />

version of House, which premiered<br />

on the <strong>Goodman</strong> mainstage in the spring<br />

of 1982. Now subtitled by the author<br />

“A Gothic Comedy,” the new version<br />

expanded the expressionistic absurdities<br />

of its earlier drafts, revealing even more<br />

passionately the playwright’s own frustrations<br />

with the challenges of aging; as<br />

Richard Christiansen noted in his Chicago<br />

Tribune review, “it is a loud, harsh, bitter<br />

pain-filled shriek at the degenerative process<br />

of life…a tantalizing and frustrating<br />

creation.” A House Not Meant to Stand<br />

would be the last production with which<br />

Williams himself would be associated;<br />

tragically, he died nine months later.<br />

7

IN THE ALBERT<br />

A Journey into “Bieitoland”:<br />

Introducing the Unconventional<br />

World of Director Calixto Bieito<br />

By Tanya Palmer<br />

Fluent in five languages, Bieito has juggled<br />

a career in his native Spain—where<br />

he was the artistic director of Barcelona’s<br />

Teatre Romea from 1999 to 2011—with<br />

an international career directing primarily<br />

opera around the globe. His work<br />

has taken him to Germany, Belgium, the<br />

United Kingdom, Scandinavia, France,<br />

Italy, Switzerland, South America and<br />

Mexico, but his upcoming collaboration<br />

with the <strong>Goodman</strong> will mark only the second<br />

time his work will have been seen in<br />

the United States, and his first collaboration<br />

with American actors and designers<br />

on the work of an American playwright.<br />

Over the past 15 years, Spanish director<br />

Calixto Bieito has earned a reputation<br />

as a “bad boy” of European theater,<br />

simultaneously admired and reviled<br />

for his radical revisionist productions<br />

of classic operas and dramatic texts.<br />

His harshest critics have condemned<br />

his work as “sickening,” “puerile” and<br />

“tasteless,” while his advocates describe<br />

him as a “director of vision and courage,<br />

an Almodóvar of the opera stage.” His<br />

most famous (or infamous) productions<br />

include a version of Verdi’s A Masked<br />

Ball at the English National Opera<br />

(in a co-production with the Liceu in<br />

Barcelona and the Royal Danish Opera)<br />

which relocated the mise-en-scene from<br />

eighteenth century Sweden to 1970s<br />

Spain and began with a controversial<br />

image of a vast public urinal; a staging<br />

of Macbeth (first produced in German for<br />

the Salzburg Festival and then restaged<br />

in Catalan at Teatre Romea) in which the<br />

characters were cast as mafia dons and<br />

molls, monarchs of what one reviewer<br />

called a “hedonistic, drug and drinkfuelled<br />

culture with no bounds” on a set<br />

of garish white leather sofas, cluttered<br />

drink trolleys and porcelain tigers growling<br />

ominously at passersby; and a production<br />

of Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s<br />

Golden Age classic Life is a Dream,<br />

which Bieito staged on a gray sandy set<br />

dominated by a giant suspended mirror<br />

which functioned as a “metaphorical<br />

tool, providing both a dazzling image<br />

of an elusive world that can never be<br />

entirely controlled and a commentary on<br />

a play that continuously questions what<br />

we mean by ‘reality’ and ‘fiction.’”<br />

While some critics accuse Bieito of desecrating<br />

classic texts with needlessly<br />

shocking images of violence and sexuality,<br />

his work is the result of a conscious<br />

approach to create a visceral connection<br />

between contemporary audiences and<br />

classic works. Theater scholar Maria<br />

Delgado suggests that Bieito’s work consistently<br />

asks radical questions about how<br />

and what texts mean to different generations.<br />

In a profile of Bieito in Fifty Key<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> Directors, a book that explores<br />

the work of directors from around the<br />

world who “have shaped and pushed<br />

back the boundaries of theater and performance,”<br />

Delgado writes, “With the<br />

classics especially, he has demonstrated<br />

the ability to reinvent texts, stripping them<br />

of the legacy of past productions and<br />

reimagining them for contemporary audiences.”<br />

This method of “reinventing texts”<br />

often involves working closely with a<br />

translator and/or adaptor to cut and rearrange<br />

canonical works—deleting characters<br />

and interpolating contemporary musical<br />

or cinematic references into the performance<br />

texts, such as a 2004 production<br />

of King Lear which contained depictions<br />

of violence that were a direct homage to<br />

the final sequences of Kill Bill and The<br />

Texas Chainsaw Massacre. For Bieito, this<br />

process of connecting the dramatic text or<br />

opera to the contemporary moment—and<br />

locating himself and his collaborators<br />

within the work—all begins with an effort<br />

to interpret what the writer was trying to<br />

communicate. Rather than simply laying<br />

on a concept, Bieito’s goal is to create a<br />

visual and auditory universe that releases<br />

the text from the confines of history—thus<br />

unlocking its meaning and connecting it<br />

8

Rather than simply laying on a concept,<br />

Bieito’s goal is to create a visual and<br />

auditory universe that releases the text<br />

from the confines of history—thus<br />

unlocking its meaning and connecting<br />

it more directly to the present moment.<br />

more directly to the present moment. In a<br />

recent conversation with the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s<br />

Associate Dramaturg, Neena Arndt, Bieito<br />

explained his process this way:<br />

I have a way of approaching the text,<br />

I have to prepare…reading a lot about<br />

the context, the period, about the<br />

writer. In this case, with Tennessee<br />

Williams, there are his Memoirs. After<br />

that, you think—what was the writer<br />

trying to do? And what does it mean<br />

for the audience, today, or what does<br />

it mean to me today? And what can<br />

I express of myself with this?<br />

Bieito first came to prominence internationally<br />

in 1997, when his production<br />

of Tómas Bretón’s 1894 zarzuela<br />

(or popular operetta) La verbena de la<br />

paloma (The Festival of the Dove) was<br />

performed at the Edinburgh International<br />

Festival. Setting the piece in an urban<br />

wasteland, Bieito’s production undermined<br />

the “celebratory tone” in which<br />

the piece was generally read, presenting<br />

it instead through the “prism of an overt<br />

social criticism of bourgeois complacency<br />

and corruption.” The production marked<br />

Bieito as an important and original<br />

young voice, but by that time he was<br />

already well known in his native Spain,<br />

where he’d built a reputation tackling a<br />

wide variety of texts—everything from<br />

Shakespeare to Sondheim.<br />

Born in 1963 in a small Spanish town<br />

called Miranda de Ebro, Bieito moved<br />

to Barcelona at the age of 14. He came<br />

of age in the final days of the Franco<br />

regime and was educated by Jesuits.<br />

Bieito grew up in a musical household—<br />

his mother was an amateur singer and<br />

his brother teaches in the Barcelona<br />

Conservatoire—and went on to study art<br />

history at the University of Barcelona. As<br />

a young man he traveled around Europe,<br />

studying and working alongside some of<br />

the continent’s most visionary directors,<br />

including Jerzy Grotowski, Peter Brook,<br />

Giorgio Strehler and Ingmar Bergman.<br />

He made his professional debut in the<br />

mid-1980s at Barcelona’s Adrià Gual<br />

theater with a production of Marivaux’s<br />

The Game of Love and Chance. His<br />

directorial approach—marked by rigorous<br />

textual readings of complex dramatic<br />

works that evolved on sparse stage environments<br />

where décor is reduced to its<br />

bare essentials—was in many ways at<br />

odds with the Spanish, and in particular<br />

Catalan, theater scene at the time, which<br />

was defined in large part by the acrobatic<br />

ingenuity of non-text based performance<br />

companies like Els Joglars, Comediants<br />

and La Fura dels Baus.<br />

From the beginning of his career, Bieito<br />

has sought to balance his identity as a<br />

Catalan director with his interest in working<br />

across linguistic and cultural boundaries.<br />

“Bieito is one of the few Catalanbased<br />

directors who has consciously<br />

sought to work both in Catalan and<br />

Castilian,” explains Maria Delgado in her<br />

article “Calixto Bieito: A Catalan Director<br />

on the International Stage.” “He has<br />

OPPOSITE: Director<br />

Calixto Bieito at Teatre<br />

Romea. Photo by David<br />

Ruano. RIGHT (left to<br />

right): Don Carlos, by<br />

Friedich Schiller. 2009.<br />

Production: Teatre<br />

Romea & Nationaltheater<br />

Mannheim. Tirant lo<br />

Blanc, 2007. Production:<br />

Teatre Romea, Institut<br />

Ramon Llull, Hebbel am<br />

Ufer, Schauspielfrankfurt<br />

& Ajuntament de<br />

Viladecans.<br />

9

IN THE ALBERT<br />

LEFT: La Ópera de Cuatro Cuartos (The Threepenny<br />

Opera), 2002. Production: Focus, Salamanca 2002,<br />

Festival d’estiu de Barcelona Grec 2002 & Teatro Cuyás.<br />

OPPOSITE: La Vida es Sueño (Life is a Dream), 2010,<br />

Production: Teatre Romea & Complejo Tetral de Buenos<br />

Aires. Photographer Carlos Furman<br />

seem like a Sunday school play.” For<br />

Falls, the production engendered in him<br />

an emotional response that convinced him<br />

to seek out more of Bieito’s work:<br />

resisted the monolingual register favored<br />

first by Franco—who promoted Castilian<br />

at the expense of the other languages<br />

of the Spanish state—and later by Jordi<br />

Pujol, president of the Catalan Parliament<br />

between 1980 and 2003, who sought to<br />

remedy the balance by prioritizing Catalan<br />

as the official language of Catalonia.”<br />

As the artistic director of Teatre Romea,<br />

which began its long history as a home<br />

for Catalan-language drama, Bieito<br />

sought to expand the theater’s mission<br />

to include presentations of contemporary<br />

European plays and reimagined classics<br />

alongside contemporary and classical<br />

Catalan plays. But while he has sought<br />

to break down linguistic and cultural barriers<br />

in his work, he continues to identify<br />

strongly with his heritage:<br />

My references come from my Catalan,<br />

Hispanic and Mediterranean culture.<br />

From the Spanish Golden Age, Valle-<br />

Inclán, Buñuel, Goya…. The black<br />

humor that shapes my work is part<br />

of this cultural heritage. Spain is not<br />

only about flamenco and bullfighting.<br />

It’s part of my imagination. It’s an<br />

approach to everything I direct.<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> Artistic Director Robert<br />

Falls knew Bieito by reputation, but his<br />

first encounter with Bieito’s work came<br />

in 2004 with his staging of Mozart’s The<br />

Abduction from the Seraglio for Berlin’s<br />

Komische Oper. In what would become<br />

a notorious production, Bieito dispensed<br />

with the traditionally “light” opera’s<br />

Turkish setting, locating it instead in a<br />

modern day European brothel modeled<br />

after one that sits near Berlin’s Olympic<br />

stadium. The cast, including a contingent<br />

of sex workers, displayed their wares in a<br />

series of transparent boxes. As one critic<br />

put it, “there [was] enough onstage sex<br />

and nudity to make the golden calf orgy in<br />

the Met’s production of Moses and Aaron<br />

“I thought that Calixto could illuminate<br />

this play in a way that some American<br />

directors might not be able to, that he’d<br />

identify it is a poem, rather than a play<br />

by an American southern playwright.”<br />

—Robert Falls<br />

I find it hard to be shocked in the theater.<br />

And this production shocked me.<br />

Coming in I didn’t know much about<br />

The Abduction from the Seraglio; but<br />

I was so taken by it and disturbed by<br />

it—and to me that is a good thing,<br />

because I don’t often feel that way in<br />

confronting art. Generally when I see<br />

a painting or listen to music or watch<br />

a play I may like it, I may think it was<br />

good, but in terms of being viscerally<br />

stimulated or disturbed, I don’t feel<br />

that way very often. I had a profound<br />

reaction to that Mozart opera. It sent<br />

me back to listen to the music and<br />

study the libretto, at which point I<br />

realized that the story is very much<br />

about rape and the subjugation of<br />

women. Calixto put those images of<br />

subjugation and domination on the<br />

surface in a way I felt was brave and<br />

profound. I felt that he was unabashedly<br />

and fearlessly trying to reveal<br />

something deep in the subtext of the<br />

work, and that inspired me in my own<br />

work. At the time I was preparing my<br />

production of King Lear, and I was<br />

seeking courage. He provided me the<br />

inspiration to go further in examining<br />

what the play was really about, and to<br />

not be afraid of presenting the horrors<br />

of the world to an audience.<br />

Falls initially approached Bieito about<br />

directing a Eugene O’Neill play as part<br />

of the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s 2009 festival, A<br />

Global Exploration: Eugene O’Neill in<br />

the Twenty-First Century. But ultimately<br />

their conversation turned to another<br />

10

major American playwright: Tennessee<br />

Williams. Bieito was familiar with the<br />

more widely known Williams plays like<br />

A Streetcar Named Desire and The<br />

Glass Menagerie, but it was Falls who<br />

introduced him to Camino Real. With its<br />

inclusion of the iconic Spanish literary<br />

figure Don Quixote, its Latin American<br />

setting, and its surreal, dreamlike musicality,<br />

Falls felt that Bieito might respond<br />

to it—and he was right. Falls was excited<br />

to see what this distinctly European<br />

director would uncover in the work of an<br />

iconic American playwright. “We think of<br />

Tennessee Williams as a realist. I think<br />

Williams was trampled down by the<br />

general conformity of the 1950s and the<br />

rise of the method actor, some of whom<br />

brought everything down to a non-poetic,<br />

mumbly, grumbly realism. And Williams<br />

was a real poet. I thought that Calixto<br />

could illuminate this play in a way that<br />

some American directors might not be<br />

able to, that he’d identify it as a poem,<br />

rather than a play by an American southern<br />

playwright.”<br />

Williams saw this play as an attempt to<br />

challenge himself, his audience—and the<br />

theater as a form, writing in the play’s<br />

foreword that his intention was “to give<br />

audiences…the continually dissolving<br />

and transforming images of a dream.”<br />

He writes, “We all have in our conscious<br />

and unconscious minds a great vocabulary<br />

of images, and I think all human<br />

communication is based on these images<br />

as are our dreams; and a symbol in a<br />

play has only one legitimate purpose<br />

which is to say a thing more directly and<br />

simply and beautifully than it could be<br />

said in words.” This wild dreamscape—<br />

this reliance on a striking image to reveal<br />

what a torrent of words cannot—makes<br />

Williams’ play a remarkable match for<br />

Calixto Bieito’s approach, in which a<br />

text and the theatrical space are stripped<br />

to their bare essentials, as Delgado<br />

explains, “allowing the construction of a<br />

multi-dimensional world where the real<br />

and the poetic can exist cheek by jowl.”<br />

When asked what he sees as the role of<br />

the director in approaching a play, Bieito<br />

explains his task this way:<br />

To understand the play. In your way.<br />

To be honest with yourself, and be<br />

brave. And to express yourself with<br />

the piece. To others…and sometimes<br />

you don’t know exactly what you<br />

want to do; you have an intuition, you<br />

have to follow this. Sometimes I am<br />

sleeping and I have a dream…and<br />

suddenly in the dream I have images<br />

that come into my mind and I use<br />

them the next day in the process…I<br />

try to feel free, to feel open, to feel<br />

naked. You have to give answers, but<br />

you have to keep the mysteries, the<br />

hidden things of the play, keep them<br />

hidden as well.<br />

INDIVIDUAL SPONSORS<br />

FOR CAMINO REAL<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> would like to thank the following<br />

individuals for their support of Camino Real.<br />

M. Ann O’Brien<br />

Orli and Bill Staley<br />

Randy and Lisa White<br />

Sallyan Windt<br />

Director’s Society Sponsors<br />

Katherine A. Abelson and Robert J. Cornell<br />

Education and Community Engagement<br />

Programs Sponsors<br />

Commitments as of January 23, 2012.<br />

11

IN THE OWEN<br />

A Conversation with Cándido Tirado<br />

This spring marks the second production<br />

in the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s ongoing collaboration<br />

with Teatro Vista, Chicago’s largest<br />

Equity theater company dedicated<br />

to producing Latino-oriented works<br />

in English. Starting April 7, the world<br />

premiere of Cándido Tirado’s Fish<br />

Men will take to the Owen stage. Set<br />

in Manhattan’s Washington Square<br />

Park, Fish Men chronicles an afternoon<br />

with a group of chess hustlers as they<br />

attempt to lure unsuspecting “fish” into<br />

high-stakes games for cash. But the<br />

action—played out rapid-fire in real<br />

time—quickly leads to a series of devastating<br />

revelations.<br />

Playwright Cándido Tirado is Teatro<br />

Vista’s writer-in-residence this season,<br />

and while Fish Men contains only<br />

one Latino character, director Edward<br />

Torres—also Teatro Vista’s artistic director—maintains<br />

that the play’s multiethnic<br />

focus is an essential element of its<br />

Latino identity. “The urban landscape<br />

has shifted dramatically, and I define<br />

‘Latino’ now as being at the center of<br />

world cultures—African, indigenous<br />

European and Asian—because for me<br />

Latino culture is rooted in all these other<br />

cultures,” he says. With this shift in the<br />

cultural landscape in mind, Fish Men<br />

also represents a first step in a change<br />

of direction for Teatro Vista towards presenting<br />

more multicultural work. Says<br />

Torres, “We hope to present the work<br />

of fresh Latino writers from their unique<br />

perspective and the world they’re living<br />

in, which is often at the intersection of<br />

many different cultures.”<br />

It is precisely at this intersection of<br />

cultures that the Fish Men playwright<br />

Tirado spent his formative years. A<br />

native-born Puerto Rican, he immigrated<br />

to the Bronx at age 11 and came of age<br />

in a densely populated neighborhood<br />

where people of myriad cultures converged.<br />

Just before rehearsals began, he<br />

talked to the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s Lesley Gibson<br />

about chess, Latino theater and how his<br />

experience as a live witness of the events<br />

of 9/11 informed this new play.<br />

Lesley Gibson: What was your initial<br />

inspiration for Fish Men?<br />

Cándido Tirado: I’m a chess master<br />

myself, and it’s one of my greatest loves.<br />

I’d been trying to work on a play about<br />

chess and had a lot of false starts. Then<br />

one day I was out with a friend and we<br />

walked into Washington Square Park and<br />

the play came to me like a wave. My<br />

initial inspiration was to make the play<br />

about hustlers. But man’s inhumanity to<br />

man is a big theme in my life, and I’ve<br />

always wanted to write about it because<br />

that’s a great interest of mine—how we<br />

treat each other and how things like<br />

genocides happen; there were so many<br />

genocides in the twentieth century.<br />

So I decided to try to deal with that<br />

subject in the context of a chess hustle,<br />

where the hustler is trying to almost<br />

dehumanize his opponent, not just over<br />

the [chess] board but psychologically to<br />

make him feel worthless, to make him<br />

feel less-than, to break him down so<br />

he’ll be easier to beat. There’s a type<br />

of psychological war that happens. So<br />

instead of just being a play about playing<br />

chess, it becomes about life and death.<br />

LG: Did you spend a lot of time in the<br />

park researching and playing chess?<br />

CT: I always go to the park to play. I<br />

used to hang out to listen to people<br />

talk. Chess players are very funny, and<br />

a lot of them are a little bit more than<br />

acquaintances; we talk often. So that’s<br />

part of my world, whenever I walk in<br />

SUPPORT FOR FISH MEN<br />

The <strong>Goodman</strong> is proud to acknowledge the following<br />

sponsors who support our dedication to<br />

producing new work including Fish Men.<br />

Julie and Roger Baskes<br />

Lynn Hauser and Neil Ross<br />

Cindy and Andrew H. Kalnow<br />

Eva Losacco<br />

Catherine Mouly and LeRoy T. Carlson, Jr.<br />

Shaw Family Supporting Organization<br />

Beth and Alan Singer<br />

Orli and Bill Staley<br />

New Work Season Sponsors<br />

Harry and Marcy Harczak<br />

New Work Student Subscription Series Sponsor<br />

The Davee Foundation<br />

Major Contributor to Research and Development<br />

of New Work<br />

Contributing Sponsor for Fish Men<br />

Commitments as of January 23, 2012.<br />

12

OPPOSITE: Cándido<br />

Tirado. RIGHT: Steve<br />

Casillas, Jessie David<br />

and Marvin Quijada in<br />

Mamma’s Boyz. Photo<br />

by Art Carrillo.<br />

there everybody says, “Hey, Tirado!”<br />

And I love that, because it’s like Cheers,<br />

where everybody knows your name.<br />

They make you feel welcome for a little<br />

while, then they just want to play you<br />

and try to beat you. But for five minutes<br />

it’s good.<br />

LG: Are any of these characters based<br />

on actual people you played with in<br />

the park?<br />

CT: They’re basically composites of<br />

people. Flash is a composite of three<br />

different people; I knew a guy who was<br />

really brilliant but he dropped out of<br />

school and became a hustler. Nobody<br />

knew why he dropped out of school,<br />

but he was really intellectual, he had a<br />

fast mouth and he could beat you with<br />

his mouth he talked so much. He was a<br />

great trash-talker but he was also nerdy,<br />

so in order to create the character Flash<br />

I wanted to give him more street toughness.<br />

I know another hustler who was<br />

more “street” who could confront you—<br />

because when you’re hustling you got to<br />

get tough. Sometimes the people losing<br />

don’t like losing; not everyone wants to<br />

give you their money, and sometimes<br />

you have to make a stand or a threat.<br />

So I wanted to make this character live<br />

in both worlds; have a kind of a street<br />

toughness and an intellectual side. But<br />

some of the other characters are totally<br />

fictional or are based on situations I’ve<br />

seen that I’ve taken creative license with.<br />

LG: The characters in this play come<br />

from all different backgrounds; only one<br />

of them is Latino. Do you think of this<br />

as a “Latino play”?<br />

CT: I don’t; that’s my quick answer. For<br />

me, the central theme of Fish Men is<br />

whether human beings are going to continue<br />

on this planet. So the characters in<br />

the play come from different ethnicities—<br />

there’s only one Latino character—but<br />

he’s a major character because I wanted<br />

to talk about some part of a Latino/<br />

Indian genocide that happened. So I don’t<br />

consider the play a Latino play, but I’m<br />

Latino, and I wrote it so I guess it is.<br />

“There’s a type of psychological war<br />

that happens. So instead of just being<br />

a play about playing chess, it becomes<br />

about life and death.”<br />

—Cándido Tirado<br />

In this country everybody gets defined<br />

by their background. So I’m a Latino<br />

playwright in this country. But the plays<br />

I write—I like to do more symbolic characters,<br />

I like to do metaphorical characters.<br />

In Mamma’s Boyz, one of my plays<br />

that Teatro Vista just produced, there<br />

are three young drug dealers whose<br />

names are Mimic, Shine and Thug.<br />

Each name means something, but they<br />

don’t have to be Latino actors to play<br />

them. They could be Italian or Irish or<br />

African American; as long as their culture<br />

is that of the street, impoverished,<br />

where drugs or crime seem like a way<br />

out. I had a friend from Italy who saw<br />

the play said, “Wow, that seems like me<br />

and my two friends.”<br />

LG: You mentioned in a previous interview<br />

that you were in lower Manhattan<br />

on September 11, 2001; did your<br />

experience that day affect your work<br />

on this play?<br />

CT: It did, a lot. After the first plane hit I<br />

was still going to work—I worked across<br />

the street from the second tower that got<br />

hit. There was a policeman in the middle<br />

of the street—it had just happened—and<br />

he was blowing his whistle and telling<br />

people, “Don’t go that way,” but people<br />

13

IN THE OWEN<br />

weren’t listening. But he looked me in<br />

the eyes and told me not to go where I<br />

was going, so I walked away, and about<br />

two minutes later the second plane hit; I<br />

would have been underneath that building<br />

when the second plane hit. With all<br />

the glass and parts that were falling I<br />

probably would have been really hurt or<br />

killed. I ended up walking home across<br />

the Brooklyn Bridge, and there was a<br />

lot of fear and adrenalin, because at the<br />

time I thought, “If they hit the building<br />

they’re going to hit the bridge too,”<br />

which sounds dramatic now but it’s<br />

what I was thinking.<br />

For a while after I got really depressed—<br />

coming so close, being there, and then<br />

dealing with a lot of survivor’s guilt. It<br />

informed me about the play, and about<br />

the characters, and how big this thing<br />

is—man’s inhumanity to man. There<br />

are characters in the play who lost their<br />

family; I could never get close to that<br />

and I hope I never will, but I got a little<br />

taste—a very small taste—of that.<br />

thing that brought everybody together,<br />

and that feeling was amazing. The fear<br />

was horrible, but this spiritual thing was<br />

amazing, and that informed in me in the<br />

play because I think that’s very special<br />

in humanity.<br />

LG: Do you think your chess skills seep<br />

over into your process as a playwright?<br />

CT: People tell me that the way I think<br />

is like a chess player. In chess there’s<br />

something called a “trio of analysis.” You<br />

analyze a few variations of a move, and<br />

each variation has all of these branches,<br />

so it could go on forever, but you usually<br />

pick the top three responses and analyze<br />

them to see which has the best payoff.<br />

And I look at writing like that—I analyze<br />

the possible ways of doing something,<br />

and sometimes I take the least likely<br />

way to get to that place. People tell me<br />

all the time, “The way you just made<br />

that point is like a chess player.” I really<br />

don’t get it because that’s how I think<br />

naturally. I’m a playwright; I think about<br />

structure and form and how you make<br />

a play, and I also know chess and the<br />

argument of chess. So maybe writing a<br />

play and playing chess are more similar<br />

than they appear.<br />

BELOW: Steve Casillas and Jessie David in Tirado’s<br />

Mamma’s Boyz. Photo by Art Carrillo.<br />

But then at the same time as I was coming<br />

out of my depression and my fear<br />

and all that stuff, there was kind of a<br />

spiritual thing going on in New York. You<br />

know, if the recovery workers needed<br />

socks, in an hour they had too many<br />

socks. If they said, “We need blood,”<br />

in an hour they had too much blood,<br />

and they kept making announcements,<br />

you know: “Stop giving blood, stop giving<br />

socks.” So there was this spiritual<br />

GOODMAN THEATRE WOULD<br />

LIKE TO THANK ALL NEW WORK<br />

DONORS FOR THEIR HELP IN<br />

MAKING OUR PRODUCTION OF<br />

FISH MEN POSSIBLE.<br />

14

For Love or Money:<br />

The World of Chess<br />

Hustling<br />

By Steve Scott<br />

They can be found in any of New York’s<br />

public parks or gathered in chess shops<br />

throughout the city. Their names evoke<br />

the legendary status that some of them<br />

achieve: Broadway Bobby, Russian<br />

Paul, Sweet Pea, Poe. Their ranks<br />

have included future Hollywood greats,<br />

day laborers, students, international<br />

champions and homeless knockabouts.<br />

Although the trade that they ply is technically<br />

illegal, they are largely ignored<br />

by legal authorities—and their unique<br />

brand of fame has been chronicled by<br />

newspapers, blog sites and at least one<br />

feature film.<br />

Welcome to the world of chess hustlers,<br />

players who compete at the<br />

board game for money, a fixture of New<br />

York street life that has been referred<br />

to as the “largest growth industry”<br />

in the city. Chess hustlers have plied<br />

their trade in Manhattan’s parks for<br />

decades; according to local lore, actor<br />

Humphrey Bogart made his living as<br />

a master of speed chess during the<br />

Depression, as did future Unites States<br />

chess champion Arnold Denker. Film<br />

director Stanley Kubrick (whose passion<br />

for the game made its way into such<br />

movies as 2001: A Space Odyssey)<br />

was a frequent—and victorious—habitué<br />

of Washington Square Park’s chess<br />

boards in the early 1960s. But the<br />

popularity of street chess is generally<br />

acknowledged to have started with a<br />

former convict named Bobby Hayward,<br />

who in the late 1960s or early 1970s<br />

set up shop on a garbage can on<br />

Eighth Avenue, between 42nd and<br />

43rd Streets. Word soon spread, and<br />

Hayward’s enterprise was immortalized<br />

by photographs in The New York Times.<br />

Such mainstream attention brought<br />

visibility (and perhaps legitimacy) to<br />

Hayward and his fellow hustlers, and<br />

soon street chess was a sought-after<br />

activity for both chess wizards and New<br />

York tourists.<br />

The form of the game preferred by most<br />

hustlers is known variously as speed<br />

chess, blitz chess, or lightning, in which<br />

each side has five minutes (or three,<br />

in a variation known as bullet chess)<br />

to complete all their moves. There are<br />

two ways to play speed chess: touchmove<br />

(meaning that if a player touches<br />

a piece, he has to move it) or the more<br />

common clock-move (meaning that a<br />

move is not complete until a player<br />

punches the clock). Veteran speed chess<br />

players can keep several games going at<br />

once, keeping track of the tally as they<br />

go. This can be an effective method of<br />

bilking more money out of the neophyte<br />

player by causing him to lose track of<br />

the number of games that have actually<br />

been won, or to lose track of the amount<br />

of the wager made on each game. There<br />

are other tricks that the hustler can use<br />

to fix the outcome of a game: rigging the<br />

clock so that the opponent’s time runs<br />

out faster than the hustler’s or, when a<br />

hustler’s luck runs out, fleeing the game<br />

via an unannounced break. In his 2000<br />

book The Virtue of Prosperity, author<br />

Dinesh D’Souza describes one such<br />

game in which his opponent, a storied<br />

street chess champion, was unexpectedly<br />

down after fifteen minutes. “I’ll be<br />

right back,” the opponent said, heading<br />

for the men’s room in a hotel across<br />

from the park. A few minutes later,<br />

an observer pointed out the obvious<br />

to D’Souza: the hustler wasn’t coming<br />

back, and D’Souza wasn’t getting his<br />

five-buck winnings.<br />

ABOVE: Chess hustlers in Washington Square Park.<br />

Photo by David Shankbone.<br />

Although such shenanigans are eschewed<br />

by many bona fide chess hustlers, the<br />

competition among hustlers is fierce,<br />

and the stakes may be higher than the<br />

monetary bet at hand. As the character<br />

Flash in Cándido Tirado’s Fish Men says,<br />

“We’re not happy with just winning. We<br />

want to obliterate the opposition.”<br />

GOODMAN THEATRE<br />

WINS 2011 EDGERTON<br />

FOUNDATION NEW<br />

AMERICAN PLAYS AWARD<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> is the proud recipient of a<br />

2011 Edgerton Foundation New American Plays<br />

Award, to support its world-premiere production<br />

of Cándido Tirado’s Fish Men. Since it launched<br />

nationally in 2007, the Edgerton Foundation New<br />

American Plays program has awarded grants to<br />

not-for-profit theaters for 150 new plays. The<br />

awards are competitively granted to theaters to<br />

give plays-in-development extended rehearsal<br />

time, allowing the production and its theater artists<br />

the opportunity to reach their maximum potential.<br />

Past awards from the Edgerton Foundation include<br />

support for the world-premiere productions of<br />

Chinglish, Stage Kiss and Turn of the Century.<br />

15

AT THE GOODMAN<br />

Want to Learn More About What<br />

Inspires the Work on Our Stages?<br />

Discover the Insider Access Series.<br />

Insider Access is a series of public programs that provide insight into the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s artistic process. With Artist Encounters,<br />

you’ll meet the names and faces behind the work on our stages—actors, playwrights, directors, the gamut! And PlayBacks take<br />

place directly after selected performances; they’re the ideal chance for audiences and artists to interact and analyze the production<br />

right after the curtain comes down.<br />

CAMINO REAL<br />

ARTIST ENCOUNTER: CAMINO REAL<br />

A Conversation with Calixto Bieito<br />

Sunday, March 11 | 5 – 6pm<br />

Institito Cervantes | 31 West Ohio Street, Chicago, IL<br />

In this one-night-only event, internationally acclaimed director<br />

Calixto Bieito takes us inside his new adaptation of Tennessee<br />

Williams’ fantastical 1953 play, Camino Real, in an intimate<br />

conversation with <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> Resident Artistic Associate<br />

Henry Godinez. Dubbed “one of Williams’ most imaginative<br />

works” by The New York Times, Camino Real is a rarely performed<br />

carnival of desire and temptation; this production marks<br />

the first original collaboration with an American theater for<br />

Bieito, who is known throughout Europe for his radical revisionist<br />

interpretations of classic operas and plays.<br />

FREE, reserve tickets at <strong>Goodman</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>.org or 312.443.3800.<br />

FISH MEN<br />

ARTIST ENCOUNTER: FISH MEN<br />

Featuring playwright Cándido Tirado and director Edward Torres<br />

Wednesday, April 11 | 6 – 7pm<br />

Chicago Cultural Center, First Floor Garland Room<br />

78 East Washington Street, Chicago, IL<br />

Join us for an intimate conversation with Fish Men playwright Cándido<br />

Tirado and director Edward Torres before a 7:30 performance.<br />

FREE, reserve tickets at <strong>Goodman</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>.org or 312.443.3800.<br />

PLAYBACK: FISH MEN<br />

Following each Wednesday performance of Fish Men, Owen<br />

<strong>Theatre</strong> audiences are invited to attend PlayBacks, post-show<br />

discussions with members of the artistic team.<br />

FREE<br />

PLAYBACK: CAMINO REAL<br />

Following each Wednesday and Thursday performance of Camino<br />

Real, Albert <strong>Theatre</strong> audiences are invited to attend PlayBacks,<br />

post-show discussions with members of the artistic team.<br />

FREE<br />

THEATER THURSDAY: CAMINO REAL<br />

Thursday, March 8 | Reception: 6 – 7pm<br />

Performance of Camino Real at 7:30pm<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> Lobby<br />

Join us for a pre-show reception featuring internationally<br />

renowned Catalan director Calixto Bieito, co-adaptor Marc<br />

Rosich and the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s Associate Dramaturg Neena Arndt.<br />

Enjoy Spanish-themed hors d’oeuvres, beer and wine—as well<br />

as a discussion with Bieito and Rosich on their preparation and<br />

vision for the play. Then catch a performance of Camino Real,<br />

directed by Bieito, known as “the Quentin Tarantino of opera.”<br />

Tickets to the reception and play are only $50. Use promo<br />

code THURSDAY when purchasing at <strong>Goodman</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>.org,<br />

or call 312.443.3800 and mention “Theater Thursday.”<br />

Chuck Smith at the Race Artist Encounter. Photo by David Raine.<br />

INDIVIDUAL SEASON SPONSORS<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> is grateful to these individuals for their outstanding support<br />

of the 2011/2012 Season.<br />

The Edith-Marie Appleton Foundation<br />

Ruth Ann M. Gillis and<br />

Michael J. McGuinnis<br />

Principal Sponsors<br />

Sondra & Denis Healy/Turtle Wax, Inc.<br />

Merle Reskin<br />

Leadership Sponsors<br />

Julie and Roger Baskes<br />

Patricia Cox<br />

Andrew “Flip” Filipowski<br />

and Melissa Oliver<br />

Carol Prins and John H. Hart<br />

Alice Rapoport and Michael Sachs/Sg2<br />

Major Sponsors<br />

Commitments as of January 23, 2012.<br />

16

IN THE WINGS<br />

Imparting Culture and Communication:<br />

A Conversation with Ira Abrams<br />

The <strong>Goodman</strong>’s Student Subscription Series (SSS) provides<br />

matinees, post-show discussions and educational resources for<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> productions to Chicago Public School teachers and<br />

students free of charge. In return, partner teachers must provide<br />

lesson plans detailing how they use <strong>Goodman</strong> productions in<br />

the classroom, attend professional development workshops and<br />

previews for each production their students see, and organize<br />

annual school visits with the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s education department<br />

to ensure their continued participation in the series. Education<br />

Associate Teresa Rende recently spoke with one of the<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong>’s Student Subscription Series teachers, Ira Abrams,<br />

who has worked with the <strong>Goodman</strong> to bring theater to his students<br />

at the Chicago Military Academy for over eight years.<br />

Teresa Rende: What inspired you to participate in the SSS?<br />

Ira Abrams: It just seemed obvious to me that if there was this<br />

incredibly generous offer out there that my students should be<br />

able to take advantage of it. Coming to teach in the Chicago<br />

Public Schools, I could see how students often felt alienated by<br />

much of the cultural knowledge we were trying to pass on to<br />

them; the <strong>Goodman</strong> bridges that gap for students.<br />

From an instructional point of view, the <strong>Goodman</strong> program has<br />

been the cornerstone of my efforts to help students see what is<br />

possible to do with a text. My students come to the <strong>Goodman</strong><br />

having studied the script and struggled with its shape and its<br />

nuances. Then they get to compare their reading with the production.<br />

There’s a light bulb that comes on in this context and I<br />

would be hard-pressed to reproduce that kind of learning by any<br />

other means.<br />

TR: What were you hoping to impart to your students when<br />

they saw Race this January?<br />

IA: Chuck Smith, the director for Race, asked the question,<br />

“Why aren’t the races talking to each other?” It seems to me<br />

that “not talking to each other” is one of the great themes of<br />

our time. In Race, playwright David Mamet looks specifically at<br />

the way manipulating story lines and public images has become<br />

more important than genuine communication. I wanted my students<br />

to do their own writing to explore the difference between<br />

genuine communication and posturing conversation, both public<br />

and private.<br />

Ira’s Chicago Military Academy students participate in a post-show discussion with the<br />

playwright and cast of El Nogalar; April 2011.<br />

TR: What has been your favorite element of the program thus far?<br />

IA: I can think of dozens of students for whom the SSS program<br />

has been either a doorway to a bigger vision of life, or a literal<br />

life-saver. One student in particular stands out for me.<br />

This young woman had virtually dropped out of school by<br />

March, when we began studying The Story. She was very bright<br />

but had always been an inconsistent student, and now her<br />

mother had become ill and was relying on her to work and be<br />

a caregiver. Eventually, she admitted that she was planning to<br />

drop out of school and was only coming to my class because<br />

she wanted the chance to perform and to attend the plays.<br />

I made her a kind of a deal, whereby she had to meet some<br />

basic goals to earn a ticket to the show.<br />

Somehow, after the trip to see Tracey Scott Wilson’s The Story,<br />

she got a burst of energy and started coming to school. I never<br />

did figure out what it was about that play that made such a difference<br />

for her, but for the last months of the school year every<br />

time I saw her in the halls she had her ragged copy of that<br />

script tucked under her arm. She managed to graduate and is<br />

now an accountant, but theater was her double-major in college.<br />

She still acts in her church.<br />

GOODMAN THEATRE WOULD LIKE TO THANK ALL<br />

EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT DONORS<br />

FOR THEIR HELP IN MAKING OUR OUTREACH<br />

PROGRAMS POSSIBLE.<br />

17

COMING SOON…<br />

A NEW (WEB)<br />

HOME FOR THE<br />

GOODMAN!<br />

It’s the second best thing to being there. The<br />

new <strong>Goodman</strong> website will bring you closer than<br />

ever to the magic of live theater, with exhaustive<br />

archives, interactive features and new ways to<br />

experience the drama—wherever the internet<br />

may find you!<br />

ON THE NEW GOODMAN WEBSITE YOU’LL BE ABLE TO:<br />

SEARCH for the best seats and buy<br />

tickets with greater ease<br />

PURCHASE season subscriptions<br />

24/7 and even select your own seats<br />

WATCH exclusive behind-the-scenes<br />

films in our expanded video library<br />

AS WELL AS:<br />

• EXPLORE our extensive archive of all productions staged<br />

from 2000 through today<br />

• RELIVE your favorite past shows in our photo albums<br />

• LEARN more about the artists who bring the <strong>Goodman</strong>’s<br />

work to life<br />

• READ in-depth articles about productions past,<br />

present and future<br />

• PERUSE our extensive collection of actor bios<br />

• DISCOVER our programs for Chicago-area students<br />

• PLEDGE your support<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>.org<br />

EARLY SPRING, 2012<br />

18

SCENE AT THE GOODMAN<br />

Race Opening Night<br />

On January 23, 2012, sponsors and guests gathered at Club<br />

Petterino’s to celebrate the opening of David Mamet’s Race.<br />

Following cocktails and dinner, guests attended the opening performance<br />

of Mamet’s latest work.<br />

Special thanks to our sponsors who made this production possible:<br />

Corporate Sponsor Partner Mayer Brown LLP; Media Partner<br />

WBEZ 91.5 FM; Season Sponsors The Edith-Marie Appleton<br />