Download - Goodman Theatre

Download - Goodman Theatre

Download - Goodman Theatre

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

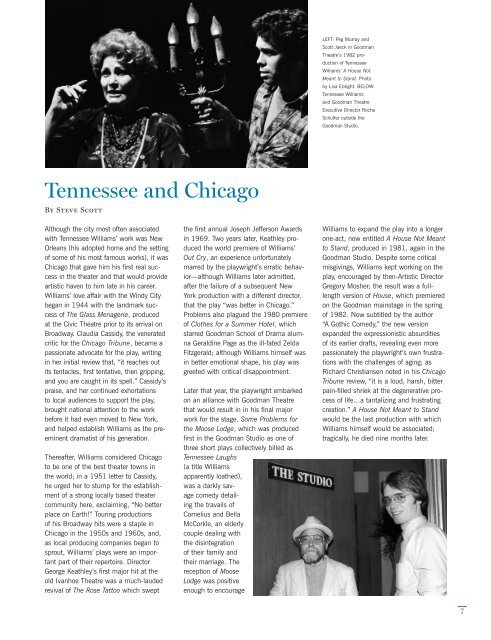

LEFT: Peg Murray and<br />

Scott Jaeck in <strong>Goodman</strong><br />

<strong>Theatre</strong>’s 1982 production<br />

of Tennessee<br />

Williams’ A House Not<br />

Meant to Stand. Photo<br />

by Lisa Ebright. BELOW:<br />

Tennessee Williams<br />

and <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

Executive Director Roche<br />

Schulfer outside the<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> Studio.<br />

Tennessee and Chicago<br />

By Steve Scott<br />

Although the city most often associated<br />

with Tennessee Williams’ work was New<br />

Orleans (his adopted home and the setting<br />

of some of his most famous works), it was<br />

Chicago that gave him his first real success<br />

in the theater and that would provide<br />

artistic haven to him late in his career.<br />

Williams’ love affair with the Windy City<br />

began in 1944 with the landmark success<br />

of The Glass Menagerie, produced<br />

at the Civic <strong>Theatre</strong> prior to its arrival on<br />

Broadway. Claudia Cassidy, the venerated<br />

critic for the Chicago Tribune, became a<br />

passionate advocate for the play, writing<br />

in her initial review that, “it reaches out<br />

its tentacles, first tentative, then gripping,<br />

and you are caught in its spell.” Cassidy’s<br />

praise, and her continued exhortations<br />

to local audiences to support the play,<br />

brought national attention to the work<br />

before it had even moved to New York,<br />

and helped establish Williams as the preeminent<br />

dramatist of his generation.<br />

Thereafter, Williams considered Chicago<br />

to be one of the best theater towns in<br />

the world; in a 1951 letter to Cassidy,<br />

he urged her to stump for the establishment<br />

of a strong locally based theater<br />

community here, exclaiming, “No better<br />

place on Earth!” Touring productions<br />

of his Broadway hits were a staple in<br />

Chicago in the 1950s and 1960s, and,<br />

as local producing companies began to<br />

sprout, Williams’ plays were an important<br />

part of their repertoire. Director<br />

George Keathley’s first major hit at the<br />

old Ivanhoe <strong>Theatre</strong> was a much-lauded<br />

revival of The Rose Tattoo which swept<br />

the first annual Joseph Jefferson Awards<br />

in 1969. Two years later, Keathley produced<br />

the world premiere of Williams’<br />

Out Cry, an experience unfortunately<br />

marred by the playwright’s erratic behavior—although<br />

Williams later admitted,<br />

after the failure of a subsequent New<br />

York production with a different director,<br />

that the play “was better in Chicago.”<br />

Problems also plagued the 1980 premiere<br />

of Clothes for a Summer Hotel, which<br />

starred <strong>Goodman</strong> School of Drama alumna<br />

Geraldine Page as the ill-fated Zelda<br />

Fitzgerald; although Williams himself was<br />

in better emotional shape, his play was<br />

greeted with critical disappointment.<br />

Later that year, the playwright embarked<br />

on an alliance with <strong>Goodman</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

that would result in in his final major<br />

work for the stage. Some Problems for<br />

the Moose Lodge, which was produced<br />

first in the <strong>Goodman</strong> Studio as one of<br />

three short plays collectively billed as<br />

Tennessee Laughs<br />

(a title Williams<br />

apparently loathed),<br />

was a darkly savage<br />

comedy detailing<br />

the travails of<br />

Cornelius and Bella<br />

McCorkle, an elderly<br />

couple dealing with<br />

the disintegration<br />

of their family and<br />

their marriage. The<br />

reception of Moose<br />

Lodge was positive<br />

enough to encourage<br />

Williams to expand the play into a longer<br />

one-act, now entitled A House Not Meant<br />

to Stand, produced in 1981, again in the<br />

<strong>Goodman</strong> Studio. Despite some critical<br />

misgivings, Williams kept working on the<br />

play, encouraged by then-Artistic Director<br />

Gregory Mosher; the result was a fulllength<br />

version of House, which premiered<br />

on the <strong>Goodman</strong> mainstage in the spring<br />

of 1982. Now subtitled by the author<br />

“A Gothic Comedy,” the new version<br />

expanded the expressionistic absurdities<br />

of its earlier drafts, revealing even more<br />

passionately the playwright’s own frustrations<br />

with the challenges of aging; as<br />

Richard Christiansen noted in his Chicago<br />

Tribune review, “it is a loud, harsh, bitter<br />

pain-filled shriek at the degenerative process<br />

of life…a tantalizing and frustrating<br />

creation.” A House Not Meant to Stand<br />

would be the last production with which<br />

Williams himself would be associated;<br />

tragically, he died nine months later.<br />

7