Metaethical subjectivism and metaethical objectivism - Ashgate

Metaethical subjectivism and metaethical objectivism - Ashgate

Metaethical subjectivism and metaethical objectivism - Ashgate

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

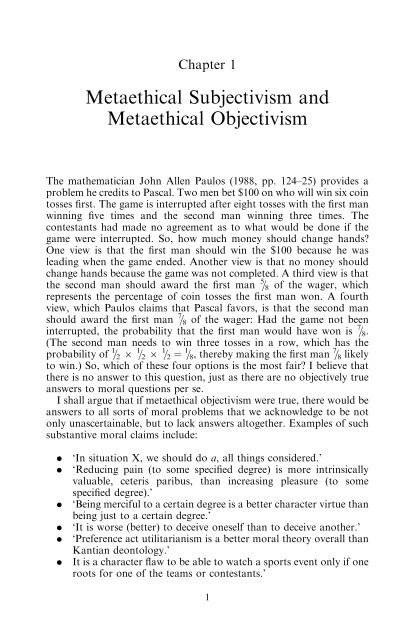

Chapter 1<br />

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism<br />

The mathematician John Allen Paulos (1988, pp. 124–25) provides a<br />

problem he credits to Pascal. Two men bet $100 on who will win six coin<br />

tosses first. The game is interrupted after eight tosses with the first man<br />

winning five times <strong>and</strong> the second man winning three times. The<br />

contestants had made no agreement as to what would be done if the<br />

game were interrupted. So, how much money should change h<strong>and</strong>s?<br />

One view is that the first man should win the $100 because he was<br />

leading when the game ended. Another view is that no money should<br />

change h<strong>and</strong>s because the game was not completed. A third view is that<br />

the second man should award the first man 5 = 8 of the wager, which<br />

represents the percentage of coin tosses the first man won. A fourth<br />

view, which Paulos claims that Pascal favors, is that the second man<br />

should award the first man 7 = 8 of the wager: Had the game not been<br />

interrupted, the probability that the first man would have won is 7 = 8 .<br />

(The second man needs to win three tosses in a row, which has the<br />

probability of 1 = 2 6 1 = 2 6 1 = 2 ¼ 1 = 8 , thereby making the first man 7 = 8 likely<br />

to win.) So, which of these four options is the most fair? I believe that<br />

there is no answer to this question, just as there are no objectively true<br />

answers to moral questions per se.<br />

I shall argue that if <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong> were true, there would be<br />

answers to all sorts of moral problems that we acknowledge to be not<br />

only unascertainable, but to lack answers altogether. Examples of such<br />

substantive moral claims include:<br />

. ‘In situation X, we should do a, all things considered.’<br />

. ‘Reducing pain (to some specified degree) is more intrinsically<br />

valuable, ceteris paribus, than increasing pleasure (to some<br />

specified degree).’<br />

. ‘Being merciful to a certain degree is a better character virtue than<br />

being just to a certain degree.’<br />

. ‘It is worse (better) to deceive oneself than to deceive another.’<br />

. ‘Preference act utilitarianism is a better moral theory overall than<br />

Kantian deontology.’<br />

. It is a character flaw to be able to watch a sports event only if one<br />

roots for one of the teams or contestants.’<br />

1

2 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

. ‘S deserves blame in this instance for doing a.’<br />

. ‘Famous minority athletes should speak out in issues concerning<br />

social injustices within their sports.’<br />

. ‘One should not try to be all things to all people.’<br />

. ‘One may never do evil, even if doing so is stipulated to prevent a<br />

greater amount of evil of the same kind.’<br />

. ‘Prosperous nations have a greater moral obligation to help their<br />

least prosperous citizens than they do to help much needier<br />

persons in less prosperous nations.’<br />

. ‘It is better (worse) for our children to be overly optimistic, poor<br />

epistemic agents, who are energized <strong>and</strong> happy than it is for them<br />

to be good epistemic agents, whose accurate cognitions make<br />

them depressed <strong>and</strong> unsuccessful’ (Seligman, 1998).<br />

These are examples of the many problems in normative ethics that I<br />

believe we can parlay into three strong arguments for <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong>.<br />

In section 1 of this chapter, I preface what I mean by ‘<strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong>.’ In section 2, I define ‘<strong>subjectivism</strong>’ <strong>and</strong> ‘<strong>objectivism</strong>’ for<br />

the three main areas of morality that I emphasize in this book: theory of<br />

moral obligation, theory of intrinsic value, <strong>and</strong> theory of character<br />

virtues. In sections 3 <strong>and</strong> 4, I discuss two types of meta-level<br />

methodological principles – metaphilosophies <strong>and</strong> intermediate-level<br />

philosophical principles – which motivate my overall argument. In<br />

section 5, I make explicit the presuppositions underlying my main<br />

argument of the book. In section 6, I anticipate an objection to that<br />

argument.<br />

1 <strong>Metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong><br />

Given the meta-level assumptions I elaborate in this chapter, the rest of<br />

the relevant beliefs I think are justified, <strong>and</strong> our conflicted moral<br />

intuitions over a multitude of moral issues, it is plausible (more than 0.5<br />

per cent likely) to think that there are no objectively true answers to the<br />

main question for normative ethics, namely, ‘What should we do, all<br />

things considered (taking into account moral obligation, intrinsic value,<br />

virtue, <strong>and</strong> all other relevant considerations)?’ Although the familiar<br />

philosophical theories of moral obligation, intrinsic value, <strong>and</strong> character<br />

virtues have much, <strong>and</strong> sometimes decisive things, to say regarding the<br />

primary question, they speak in contradictory, conflicting, <strong>and</strong><br />

incomplete voices, <strong>and</strong>, therefore, the most reasonable conclusion is<br />

<strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong>.<br />

If we look at the situation from far enough away (from Thomas<br />

Nagel’s view from nowhere), we see that the main components of

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism 3<br />

normative ethics – the theories of obligation, value, <strong>and</strong> virtue – are<br />

likely to be all objectively or all subjectively grounded. Questions about<br />

the reality of minds, personal identity, physical objects, abstract entities,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the existence of God are logically separate issues, which allow for<br />

creative metaphysicians to put together answers in various ways. The<br />

three major components of normative ethics, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, are<br />

intimately linked due to the contributions they make to the main moral<br />

question, ‘What should we do?’ Therefore, morality is more likely than<br />

nonmoral areas collectively to be entirely objective or entirely<br />

subjective. For example, if there were little reason to think that ‘What<br />

should we do?’ takes an objective answer, there would be little reason to<br />

think that the theories of moral obligation, value, <strong>and</strong> virtue are<br />

<strong>metaethical</strong>ly objective either. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, if obligation, value,<br />

<strong>and</strong> virtue were taken to be ontologically subjective, there would be<br />

little reason to think ‘What should we do?’ would take an objective<br />

answer. Even within the three components, it is difficult to see how, for<br />

example, two of the components might be objectively grounded <strong>and</strong> one<br />

of them subjective, or vice versa. The upshot is that if we can find some<br />

plausible reasons for subjectivizing any part of moral theory, we will<br />

thereby have a plausible reason to subjectivize the whole of moral<br />

metaphysics.<br />

Mine is not the first argument from normative ethics to <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong>. 1 J. L. Mackie (1977) provides two well-known arguments:<br />

the argument from the multiplicity of theories of moral obligation (the<br />

relativity argument) <strong>and</strong> the argument that moral properties would have<br />

to exemplify the strange combination of existing, yet be essentially<br />

motivating, a combination we posit nowhere else in our ontologies (the<br />

argument from queerness). Unfortunately, most <strong>metaethical</strong> objectivists<br />

think they have adequate ripostes to Mackie’s arguments. My argument<br />

in this book is in the spirit of Mackie’s, but it differs. Because I believe<br />

that moral obligation contributes only a small part of the answer to the<br />

what-should-we-do question, to find a <strong>metaethical</strong>ly objective moral<br />

theory, we should also use considerations from the theories of intrinsic<br />

value, character virtues, <strong>and</strong> other sources. When we attempt this<br />

holistic project, I think it becomes evident that any theory that there are<br />

moral truths would have to be ‘queer,’ not because they must satisfy<br />

Mackie’s internalism, but because their disorderliness makes <strong>subjectivism</strong><br />

a better explanation for them than <strong>objectivism</strong>.<br />

An obvious question to ask the author of any book such as this is<br />

how damaging to <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong> are the much-discussed<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard objections to moral theories. (See Slote, 1992 for objections to<br />

commonsense, Kantian, <strong>and</strong> utilitarian theories; Mason, ed., 1996, for<br />

discussions of moral dilemmas; Stocker, 1990, for an extended<br />

consideration of moral pluralism.) I think such objections are strong<br />

reasons for adopting <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong>. Nonetheless, I shall not

4 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

rely on that literature. First, such objections are almost always treated<br />

as threats to normative theory, not <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong>, which is my<br />

target. (Bernard Williams, 1973 offers some suggestions about the<br />

metaethics of ‘ought’ statements, but does not push very hard.) Second,<br />

such objections, when typically examined in narrow detail, inevitably<br />

invite the objectivists’ stock reply that the fact that we do not know what<br />

the correct answers are does not mean there are no correct answers – as<br />

if this truism rebuts the subjectivist challenge. Third, I propose three<br />

different challenges to <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong> that I believe are broader<br />

<strong>and</strong> more difficult to stalemate than are the more familiar subjectivist<br />

arguments, good as I think many of them are.<br />

2 Objectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong> in three areas<br />

In order to pin down my talk about ‘objectively true,’ here is how I<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> ‘<strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong>’ when applied to the three main<br />

parts of normative ethics I consider in this book:<br />

. Objectivist Moral Obligation: ‘Actions may be permissible even if<br />

all persons believe them to be forbidden, <strong>and</strong> may be forbidden<br />

even if all persons believe them to be permissible.’<br />

. Objectivist Intrinsic Value: ‘Actions (states of affairs <strong>and</strong> ways of<br />

life) may be intrinsically valuable even if all persons believe them<br />

not to be, <strong>and</strong> may lack intrinsic value even if all persons believe<br />

them to be intrinsically valuable.’<br />

. Objectivist Character Virtue: ‘Character traits may be virtuous<br />

even if all persons believe them not to be, <strong>and</strong> may lack virtue<br />

even if all persons believe them to be virtuous.’<br />

<strong>Metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong> (moral nonrealism)<br />

As the logical contradictory of <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong> (moral realism),<br />

I also equate in a single view the separately labeled theories of<br />

<strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong> or moral nonrealism. For me, <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong> is the ontological position expressed by John Steinbeck’s<br />

preacher in The Grapes of Wrath: ‘There ain’t no sin, <strong>and</strong> there ain’t no<br />

virtue. There’s just stuff people do,’ <strong>and</strong> by Hamlet: ‘There is nothing<br />

either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.’ Nietzsche expressed<br />

<strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong> this way: ‘[T]here are altogether no moral facts.<br />

Moral judgments agree with religious ones in believing in realities which<br />

are no realities’ (Nietzsche, 1954, p. 501). My version of <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong> proffers no account of what we mistakenly take moral facts<br />

to be, but simply denies that there are objective moral truths as defined<br />

above.

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism 5<br />

<strong>Metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong> is different from noncognitivism, the<br />

philosophy of language thesis that moral judgments lack truth-values<br />

because they are, for example, expressions of emotion or approval of<br />

norms, attempts at persuasion, or prescriptions. Although all the<br />

noncognitivists I know turn out to be <strong>metaethical</strong> subjectivists in my<br />

sense, I view noncognitivism as a way to argue for <strong>subjectivism</strong>, to be<br />

distinguished from <strong>subjectivism</strong>-the-metaphysical-theory, which is my<br />

thesis. To see the difference we need only consider the two conceptual<br />

possibilities that each thesis is true <strong>and</strong> the other is false. First,<br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong> might be true, even if our best philosophy of language<br />

decides that most moral judgments (those other than pure emotive<br />

ejaculations) must be treated as indicative statements <strong>and</strong>, thus, all<br />

general noncognitive analyses fail. I think ‘X is wrong’ means ‘X is<br />

forbidden’ or ‘Not X is obligatory’ or some other real synonym – it<br />

means X is really wrong, just as common sense assumes.<br />

Moreover, although moral language is used to express feelings, to<br />

recommend, to alter attitudes, to make prescriptions, <strong>and</strong> to perform<br />

other illocutionary acts, the very multiplicity of these functions seems to<br />

me strong reason to think that the meaning of moral utterances cannot<br />

be reduced to just one of these various roles. (Recall the Wittgensteinian/Austinian<br />

point that language has many functions.) Thus, it<br />

seems to me implausible on the face of it to try to show that the body of<br />

ostensibly indicative moral judgments is really so many comm<strong>and</strong>s,<br />

prescriptions, <strong>and</strong> so on. To use a Wittgensteinianism, only someone<br />

deeply under the spell of a philosophical program (for example the<br />

remains of a logical positivist methodology) would believe this.<br />

The second conceptual possibility is that there might exist objective<br />

moral facts, even if some variety of noncognitivism fully accounts for<br />

the meanings of moral judgments. For example, it is conceivable that<br />

God might exist, even if some linguistic philosophers were (contrary to<br />

fact) correct in thinking that all apparently referential statements such<br />

as ‘God loves us’ really mean statements such as ‘I have confidence in<br />

the future.’ These two possibilities show that <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong>,<br />

as I portray it, <strong>and</strong> noncognitivism are not equivalent <strong>and</strong>, indeed, do<br />

not belong in the same logical categories; <strong>subjectivism</strong> belongs to the<br />

metaphysics of ethics <strong>and</strong> noncognitivism belongs to the philosophy of<br />

language.<br />

Besides not being committed to any noncognitivist theory of moral<br />

language, <strong>metaethical</strong> subjectivists in my sense are not committed to any<br />

specific cognitivist account either. For anyone who distinguishes<br />

between the metaphysics of morals <strong>and</strong> the philosophy of language,<br />

J. L. Mackie was right to hold ‘The denial that there are objective values<br />

does not commit one to any particular view of what moral statements<br />

mean’ (1977, p. 18). Cautious <strong>metaethical</strong> subjectivists will resist being<br />

dragged into the latter issue. Thus, subjectivists need not hold that

6 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

moral claims mean the same thing as autobiographical or sociological<br />

claims, a point A. J. Ayer emphasized in Language, Truth, <strong>and</strong> Logic<br />

(1952, p. 107). For me, <strong>subjectivism</strong> does not claim that ‘X is wrong’<br />

means or has the same truth condition as ‘I (or my society) disapprove<br />

of X.’ Nor, on my account, do moral judgments such as ‘X is wrong’<br />

mean or even have the same truth conditions as more subtle claims such<br />

as ‘X has a feature that has the disposition to elicit the disapproval of<br />

normal humans’ or ‘Normal humans disapprove of X.’ Because<br />

<strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong> is the contradictory of <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong>,<br />

it simply denies that ‘X is wrong’ is capable of being objectively true.<br />

Regarding the distinction between noncognitivism <strong>and</strong> error theory,<br />

the former holds that moral judgments can be neither true nor false<br />

because they make no statements that are capable of being true or false.<br />

So, Ayer’s emotive account of moral language, though consistent with<br />

<strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong> in my sense, holds that moral judgments lack<br />

truth-values. A view such as Mackie’s, which offers an ontologically<br />

subjectivist metaethics but not a noncognitivist theory of moral<br />

judgment, holds that moral terms purport to refer but fail. This is an<br />

error theory, which holds that all moral judgments are false in the way<br />

that ‘God is merciful’ is false, according to the atheist. Although I<br />

accept some noncognitivist accounts of some moral language, I do not<br />

endorse noncognitivism, <strong>and</strong>, thus, am an error theorist.<br />

One may object: ‘If we accept <strong>subjectivism</strong>’s error theory, we see<br />

ourselves as speaking falsely when we seem to morally disagree;<br />

recognizing that this is the case, why do we continue to worry about<br />

moral disagreements?’ My answer is two-part. First, it is easy for even a<br />

subjectivist to get caught up in the heat of moral discourse <strong>and</strong><br />

temporarily talk with the objectivists as if moral judgments are true.<br />

Subjectivists care passionately about moral issues, too. Second, despite<br />

our tendency to treat subjective judgments as objective, accepting<br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong> can help us to see that our passionate disagreements are<br />

not disputes over truth. Suppose a theist were deeply worried over how<br />

God, a morally perfect Being, could be both supremely just <strong>and</strong><br />

supremely merciful? Here a subjectivist could reduce the passion by<br />

pointing out that the question presupposes <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong>: If<br />

we are subjectivists, then saying one of these qualities is morally better<br />

than the other must be an error. Although many persons prefer one trait<br />

to another, this preference is not grounded in moral facts about God,<br />

but rather in facts about the inquirers’ psychological constitutions.<br />

3 Metaphilosophies<br />

Philosophers try to accomplish different things by their moral<br />

theorizing. Some want to provide theoretical support for a moral

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism 7<br />

theory (Kagan, 1989). Others wish to provide theoretical support for<br />

moral institutions (Gauthier, 1986; Rawls, 1971). Others combine moral<br />

theory <strong>and</strong> practice, trying in their philosophical work to make<br />

audiences morally better persons (Bernstein, 1998; Noddings, 1974;<br />

Singer, 1972). Some want to find a place for reason in ethics (Rachels,<br />

1998). Some want to make sense out of their moral feelings by<br />

systematizing their moral intuitions, attitudes, <strong>and</strong> beliefs (Nagel, 1979,<br />

1986, 1991). Others want to contribute to the critical acumen of moral<br />

theorizing without promulgating any single normative theory (Williams,<br />

1981, 1997). Others, whose aim I share, want above all else to construct<br />

a picture of normative ethics <strong>and</strong> metaethics that integrates their vision<br />

of moral theory into the rest of their most plausible nonmoral theory<br />

(Harman, 1977; Mackie, 1977).<br />

I use ‘metaphilosophy’ to mean a view of what philosophy is <strong>and</strong><br />

what it is used for (Double, 1996). Any view of the purpose of a complex<br />

human activity (art, science, Little League baseball) is normative,<br />

because it reveals not only what we believe the activity can do, but what<br />

we desire the activity to accomplish or what goals of the activity we<br />

value. Metaphilosophies underpin our philosophical theorizing. Different<br />

philosophers bring different metaphilosophical stances to the<br />

problem of metaethics.<br />

Although a larger taxonomy might be more useful, I limit my<br />

discussion to two. The metaphilosophy I endorse is Philosophy as<br />

Worldview Construction. Worldview metaphilosophy tries to construct<br />

an overall view of reality that is most likely to be accurate given our<br />

most reliable sources of evidence. The particular shape that Worldview<br />

metaphilosophy takes owes to the intermediate-level methodological<br />

principles we add to our metaphilosophies. Generally speaking, I take<br />

what I regard as the best truth-finding methods of non-positivist-science<br />

<strong>and</strong> enlightened common sense as the models for philosophical theory<br />

construction: letting entities into our worldview by inference to the best<br />

explanation <strong>and</strong> excluding them by Occam’s razor. Philosophy as<br />

Worldview Construction, however, need not be enamored of scientific<br />

methods. For example, Worldview thinkers might think that phenomenology,<br />

synthetic a priori intuition, careful attention to ordinary<br />

language, appeal to commonsense beliefs, or Divine revelation are<br />

better ways to reach the most accurate worldview. Worldview thinkers<br />

may or may not sympathize with the other motivations that drive other<br />

philosophers, but, by definition, Worldview thinkers never allow those<br />

other considerations to have any weight in their attempt to arrive at the<br />

most plausible worldview, however ennobling or dispiriting that view<br />

may be.<br />

The most important opponent to Worldview metaphilosophy,<br />

Philosophy as Praxis, sees philosophy as at least partly an instrument<br />

to make the world a better place, as exemplified in Marx’s claim in his

8 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

11th thesis against Feuerbach that the point of philosophy is not to<br />

interpret the world, but to change it (Feuer, 1959, p. 245). Some Praxis<br />

metaphilosophers value worldview-building more than others do, but,<br />

by definition, all Praxis thinkers weigh what they see as the practical<br />

benefits of philosophizing against the purely theoretical aims of<br />

Worldview metaphilosophers.<br />

A Praxis thinker might think that moral urgency justifies giving nonevidential,<br />

practical considerations an evidential role in the picture of<br />

the world we construct. For example, the <strong>metaethical</strong> objectivist David<br />

Brink argues:<br />

If . . . rejection of moral realism would undermine the nature of existing<br />

practices <strong>and</strong> beliefs, then the metaphysical queerness of moral realism may<br />

seem a small price to pay to preserve these practices <strong>and</strong> beliefs. I am not<br />

claiming that the presumption in favor of moral realism could not be<br />

overturned on a posteriori metaphysical grounds. I am claiming only that<br />

we could not determine the appropriate reaction to the success of this<br />

[Mackie’s, R.D.] metaphysical argument until we determined, among other<br />

things, the strength of the presumption in favor of moral realism. (Brink,<br />

1989, pp. 173–74)<br />

Here Brink considers counting the Praxis desirability of believing in<br />

moral realism (<strong>objectivism</strong>) against the argument from ontological<br />

simplicity provided by Mackie to claim that our overall ontological<br />

picture should contain objective moral truths. This reasoning is similar<br />

to the sort William James allowed regarding the existence of God <strong>and</strong><br />

libertarian free will. I reject this kind of Praxis argument because it<br />

assigns weight in ontological theory construction to a factor that does<br />

not increase the probability of the hoped-for truths. Such wishful<br />

thinking violates Worldview scruples, although I admit that in dire<br />

enough cases it is permissible or, arguably, even morally obligatory to<br />

let down our guard against wishful thinking (Double, 1988).<br />

Here is another example of the difference between Worldview <strong>and</strong><br />

Praxis metaphilosophers. In the Supplement to Macmillan’s Encyclopedia<br />

of Philosophy (1996), Simon Blackburn reports a familiar<br />

objection against Mackie’s argument from the queerness of moral<br />

properties. Critics say that Mackie suffers<br />

from an over simple, ‘scientistic’ conception of the kind of thing as moral<br />

fact would have to be. Perhaps more fundamentally, it is not clear what<br />

clean, error-free practice the error theorist would wish to substitute for the<br />

old, error-prone ethics. That is, assuming that people living together have a<br />

need for shared practical norms, then some way of expressing <strong>and</strong> discussing<br />

those norms seems to be needed, <strong>and</strong> this is all that ethics requires.<br />

(Blackburn, 1996, p. 145)

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism 9<br />

In my terms, Mackie approaches metaethics from a Worldview<br />

perspective. For Mackie <strong>and</strong> me, if one intends to build a picture of<br />

the place of morality in the world, why not use the same methods that<br />

work best in the rest of our philosophical <strong>and</strong> scientific theory<br />

construction? Some of Mackie’s critics, however, as expressed by<br />

Blackburn, evince an additional, Praxis, motivation. Notice the end of<br />

the quote in which ‘some way of expressing <strong>and</strong> discussing those (moral)<br />

norms’ is held to be ‘all that ethics requires.’ Notice also Blackburn’s<br />

implicit dem<strong>and</strong> for a description of a ‘clean, error-free practice’ from<br />

Mackie – as if the plausibility of Mackie’s metaphysical account<br />

depends on what advantages it can provide for moral decision-making. I<br />

suggest that Mackie <strong>and</strong> those critics Blackburn characterizes are<br />

working at metaphilosophical cross-purposes. Mackie wants to<br />

construct a worldview, whereas those critics want ethics to ‘work.’ 2<br />

Because, in my view, <strong>subjectivism</strong> is probably better for normative<br />

theorizing <strong>and</strong> moral practice than is <strong>objectivism</strong>, Praxis-based defenses<br />

of <strong>objectivism</strong> are ill conceived. (See the final chapter of this book.)<br />

Nonetheless, some Praxis thinkers engage in metaethics not because<br />

they have a deep interest in ontology, but because they think that to call<br />

normative theories ‘subjective’ is to cast an aspersion upon normative<br />

theory.<br />

4 Intermediate-level methodological principles<br />

Metaphilosophies are combinations of beliefs <strong>and</strong> desires that<br />

characterize what philosophers think philosophy is <strong>and</strong> should be.<br />

Philosophers also differ due to the various strategic principles they use,<br />

which I call ‘intermediate-level methodological principles.’ Intermediate-level<br />

principles are characteristic of differing ways of approaching<br />

philosophy. To help clarify my motivation for accepting <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong>, I clarify why I endorse the intermediate principles I do, but<br />

I do not pretend to provide much argument for them. For one thing,<br />

metaphilosophies largely drive intermediate principles, <strong>and</strong> metaphilosophies<br />

themselves are desire-driven, which means to me that the latter<br />

can be neither true nor false. For another, the intermediate principles<br />

that purport to be truth tracking are so broad that they are well<br />

removed from empirical support or disconfirmation. So, there is a lot of<br />

room for disagreement over which principles are better truth-trackers.<br />

Here are some of the most important ones for moral theory, which can<br />

be viewed as differing answers to the following questions. I endorse the<br />

‘a’ position in each case.<br />

(1) Shall we accept the same theory of truth for nonmoral <strong>and</strong> moral<br />

statements ? For the sake of methodological coherence, which is a

10 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

Worldview desideratum, I think it is a virtue of any philosophical<br />

worldview to be unified regarding its theory of truth.<br />

1a. We shall give a high priority to using the same theory of truth for<br />

nonmoral <strong>and</strong> moral statements.<br />

1b. We shall not give a high priority to using the same theory of truth<br />

for nonmoral <strong>and</strong> moral statements.<br />

(2) Shall we adopt a correspondence or non-correspondence theory of<br />

nonmoral truth ? This principle is driven primarily by one’s preference<br />

for realism or idealism (anti-realism). My reason for adopting the<br />

correspondence theory is that non-correspondence theories make sense<br />

to me only if we accept idealism, as with Berkeley, or in the pragmatist/<br />

postmodernist conflation of epistemology <strong>and</strong> metaphysics. I think<br />

idealism is a worse explanation of our sensory stimulations than<br />

realism, but this is scarcely the place to try to prove the point. I have<br />

noticed in conversation that some critics of <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong><br />

take comfort from what they perceive as contemporary physics’s<br />

dalliance with idealism. Perhaps their thought is: ‘If everything is<br />

subjective, then morality is no worse than non-moral theory.’ This<br />

strikes me as Pyrrhic consolation.<br />

2a. We shall adopt a correspondence theory of truth in general.<br />

2b. We shall adopt a non-correspondence theory of truth in general.<br />

(3) Shall we use the same epistemological <strong>and</strong> other methodological tools<br />

in <strong>metaethical</strong> theory-construction as we do in nonmoral theoryconstruction<br />

? Many Worldview thinkers endorse it, but Aristotle <strong>and</strong><br />

Thomas Nagel are renowned for thinking that philosophers should use<br />

different methodologies for moral than for nonmoral subject matters. I<br />

believe that the onus of proof is on theorists who believe that different<br />

methods are appropriate for the moral <strong>and</strong> nonmoral. Aristotle’s <strong>and</strong><br />

Nagel’s claims would be acceptable if <strong>and</strong> only if we had antecedent<br />

reason to believe that objective moral theories were different from<br />

objective nonmoral theory. But that supposition is exactly what is in<br />

dispute, <strong>and</strong> it would be question-begging to use it as a methodological<br />

principle to resist <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>subjectivism</strong>.<br />

3a. In lieu of strong reasons to the contrary, we shall use the same<br />

epistemological <strong>and</strong> other methodological tools in <strong>metaethical</strong> theory<br />

construction as we do in nonmoral theory construction.<br />

3b. Even without strong antecedent reasons to the contrary, we may use<br />

different epistemological <strong>and</strong> other methodological tools in <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

theory construction than we do in nonmoral theory construction.

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism 11<br />

(4) Are desires incapable of being true or may desires be true ? I take<br />

desires in a Humean manner, that is, as logically incapable of being true.<br />

In John Searle’s terminology, a desire has a world-to-mind fit (condition<br />

of satisfaction): A desire is satisfied when the world gives us what we<br />

want. Desires may take evaluative predicates such as ‘good,’ ‘magnanimous,’<br />

<strong>and</strong> ‘wicked,’ but none of these comes close to the notion of<br />

‘true.’ Accordingly, the only sense I can give to ‘true desires’ is ‘desires<br />

that some persons really have.’ Beliefs, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, have a mindto-world<br />

fit, which means that beliefs are satisfied when the world<br />

matches the way we think the world is.<br />

4a. Desires cannot be literally true.<br />

4b. Desires can be literally true.<br />

5 Presuppositions of the main argument<br />

Because one cannot argue without presuppositions, I might as well try<br />

to indicate what mine are <strong>and</strong> why I hold them. So far as I can discover<br />

them, the presuppositions driving the main thesis of this book are as<br />

follows.<br />

(1) We can distinguish between moral judgments <strong>and</strong> nonmoral<br />

judgments. We can do this in at least two ways. First, we may make<br />

the distinction according to the speech-acts made by asserting the two.<br />

Making moral judgments entails evaluating, not just describing, human<br />

behavior in terms of its connection to human well-being. Making<br />

nonmoral judgments does not involve performing evaluations. Using<br />

the speech-act criterion, there may be some borderline cases. Second, we<br />

could make the distinction by saying that moral judgments, unlike<br />

nonmoral judgments, predicate paradigmatically moral terms such as<br />

‘good,’ ‘bad,’ ‘right,’ ‘wrong,’ ‘intrinsically valuable,’ ‘wicked,’ ‘laudable,’<br />

<strong>and</strong> so on. Here, too, there are borderline cases. Borderlines not<br />

withst<strong>and</strong>ing, if we could not make out the difference between moral<br />

<strong>and</strong> nonmoral judgments, it is difficult to see how we could pose<br />

questions about moral practice, moral theories, or metaethics.<br />

(2) For any type of discourse, philosophically it is an open question: (a)<br />

whether that discourse is capable of being true or not, <strong>and</strong> (b) if we<br />

decide it is capable of being true, what factors could make that type of<br />

discourse true?<br />

(3) Consider nonmoral judgments that presume that nonlinguistic<br />

entities exist, for example, judgments that atoms, medium-sized physical<br />

objects, persons’ psychological states, <strong>and</strong> collective social practices

12 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

exist. Here lay open questions, to be decided on whatever grounds one<br />

uses in metaphysics generally. (My naturalistic view is that all four levels<br />

exist in a pyramid fashion, each layer being ontologically dependent on<br />

the previous layers, but that presupposition is not needed for the<br />

purpose of this book.) We can defend the existence of each of the four<br />

types of entities by appealing to principles of theory construction, such<br />

as explanatory power, predictive power, <strong>and</strong> parsimony.<br />

(4) Consider nonmoral judgments that we take to be capable of being<br />

true, but are unsure whether their truth requires nonlinguistically <strong>and</strong><br />

nonconventional entities to make them true. Examples include<br />

mathematics, probability theory, logic, <strong>and</strong> the rules of games, social<br />

practices, laws, <strong>and</strong> etiquette. These areas may provide suggestive<br />

models for theories of objective moral judgments, but because the<br />

judgments they sanction (‘Bishops may move only diagonally’) are not<br />

moral judgments themselves, they provide no direct evidence that moral<br />

judgments are capable of being true.<br />

(5) Nonmoral judgments have an initially strong claim to being<br />

objectively true, <strong>and</strong> also to require nonlinguistically <strong>and</strong> nonconventional<br />

(‘realistic’) entities to provide their truth conditions. For example,<br />

postulating that Newton’s gravitational constant applies to objective<br />

spatio-temporal entities permits us to make disconfirmable, confirmed<br />

predictions of countless phenomena. Psychological postulations, though<br />

more controversial, function in a similar fashion. For example, the<br />

postulation of belief perseverance predicts that as we lose manual<br />

dexterity due to Parkinson’s disease we will tend to be late in meeting<br />

appointments (because we will tend to believe we can do things as<br />

quickly as we once could).<br />

(6) Moral judgments, although presumed to be true by common sense,<br />

less obviously require realistic truth conditions than do nonmoral<br />

judgments. As Hume <strong>and</strong> Mackie aver, it is easier to trip over a<br />

murdered body than to trip over the evil of the murder.<br />

(7) To make a great deal out of these apparent differences between<br />

nonmoral <strong>and</strong> moral theory would be to beg the central <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

question. To someone undecided about the debate between the moral<br />

objectivists <strong>and</strong> subjectivists, the differences between nonmoral <strong>and</strong><br />

moral theory seem only a matter of degree. Nonmoral theory is<br />

primary, both logically <strong>and</strong> historically, but that hardly proves much.<br />

Must nonmoral theory actually produce a true answer to each nonmoral<br />

question? No. So, in terms I shall use in chapter 2, nonmoral theory<br />

need be neither knowably sound (give only true answers to moral<br />

questions) nor knowably complete (give all the true answers there are to

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism 13<br />

moral questions). Must nonmoral theory in principle have a more<br />

inclusive body of entities within which the answers to moral questions<br />

reside? Yes. We assume there is a true nonmoral theory that could serve<br />

to provide true answers to all questions if only we were smart enough to<br />

fully underst<strong>and</strong> the theory. So, we assume that there is a nonmoral<br />

theory that is in-principle sound <strong>and</strong> complete.<br />

(8) I do not believe that moral judgments possess the same degree of inprinciple<br />

soundness <strong>and</strong> completeness that nonmoral judgments enjoy. I<br />

try to show this assumption is well founded by providing the three<br />

arguments found in chapters 5–8. But soundness <strong>and</strong> completeness are<br />

necessary requirements of any metaphysically objective theory, nonmoral<br />

or moral. The more infrequent, fragmentary, <strong>and</strong> sporadic the<br />

answers a theory gives, the more reason we have to suppose we have<br />

gotten a hold of non-objective subject matter – feelings, attitudes, <strong>and</strong><br />

false beliefs. This is why this book can be short. Because any moral<br />

theory that fails to meet soundness <strong>and</strong> completeness cannot be<br />

<strong>metaethical</strong>ly objective, that verdict holds irrespective of whether the<br />

moral theory is naturalistic, non-naturalistic, constructivist, relativist,<br />

egoistic, <strong>and</strong> so on. If my arguments are plausible, I do not have to<br />

attend to the objectivist opposition on a case-by-case (theory-by-theory)<br />

manner.<br />

(9) Assuming all this as a backdrop to the argument of this book, it does<br />

not follow that moral judgments cannot take nonlinguistic entities as<br />

truth conditions just like the judgments of realistic science. For example,<br />

so-called ‘new wave moral realism,’ could conceivably fit onto a<br />

naturalist picture by portraying moral properties as higher-level<br />

physical properties. Platonic-type views, other types of intuitionism,<br />

<strong>and</strong> even theological ethics are perhaps conceivable.<br />

(10) Nor does it follow that moral judgments cannot take conventional<br />

entities (social contracts, the structure of practical reasoning, moral<br />

constructions) to serve as truth conditions for moral judgments.<br />

(11) Nonetheless, presuppositions (1)–(6), if accepted, establish an<br />

uneven playing field against <strong>metaethical</strong> <strong>objectivism</strong> <strong>and</strong> for <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong>. Not all of the objections that I pose against moral<br />

<strong>objectivism</strong> in this book would be as plausibly available to the<br />

subjectivist about nonmoral judgments. The reason is that the<br />

antecedent plausibility of the existence of a nonlinguistic, nonconventional<br />

world ensures that when we find conflicts <strong>and</strong> lack confidence<br />

about what to say regarding nonmoral judgments, we can justifiably<br />

assign the fault as lying in us.

14 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

On the contrary, lacking a comparable conviction in an objective<br />

moral world, we have two options, not one. One, dismiss the fault as<br />

lying in us, as we would do in the nonmoral case. Two, do what Kant<br />

did with the antinomies of pure reason: Claim that the purported<br />

phenomena (space <strong>and</strong> time) do not exist except in human sensibility. In<br />

sum, without the background assumptions contained in (1)–(6), the<br />

moral objectivist has a too-easy reply to the conflicts <strong>and</strong> infelicities I<br />

emphasize in this book: ‘There’s a truth; it’s just hard to know what it<br />

is.’ I respond that by assuming (1)–(6) we can weaken that response.<br />

Readers who accept (1)–(6) will take the difficulties for moral theories I<br />

raise more seriously than those who do not.<br />

6 An objection to the above subjectivist argument<br />

Consider the following objection:<br />

Setting aside the details of any particular objectivist account, let us<br />

assume that moral truth is as de facto sound <strong>and</strong> complete in its realm<br />

as nonmoral truth is in its realm. Suppose, for example, that there is an<br />

accurate <strong>and</strong> complete deterministic theory of macroscopic physical<br />

objects such that ideally knowledgeable physicists would be able to<br />

predict the outcome of every full-bore break shot in pool ever made,<br />

indicating the exact stopping locations of each of the 16 balls. Of course,<br />

no one is in fact able to make such predictions; the relatively minor<br />

complexities of the relevant variables far outstrips our ability to sort<br />

them out <strong>and</strong> ascertain the resting locations of the balls before they are<br />

struck. But, ex hypothesi, our predictional inadequacy casts no doubt<br />

on the truth of macroscopic physical theory.<br />

By analogy, we moral objectivists can accept Double’s three<br />

arguments emphasizing the disorderly way that disparate moral factors<br />

dictate different moral answers. Let us admit that sometimes<br />

impartiality seems to carry the day, <strong>and</strong> sometimes not; that<br />

aggregationist reasoning sometimes seem superior, although at other<br />

times aggregation loses; that sometimes moral obligation, but that other<br />

times intrinsic value, <strong>and</strong> still other times character virtue determine<br />

what we should do. Even allowing all this, we need not admit that moral<br />

truths do not exist, for the same reason that our inability to predict<br />

pool-breaks does not cast doubt upon the soundness <strong>and</strong> completeness<br />

of physical theory. In one type of case, if all the other relevant<br />

conditions remain equal, the velocity of the cue ball will be the<br />

determining factor in the outcome of the shot. In a different type of<br />

case, if only the texture of the tabletop varies, the outcomes will differ<br />

depending on texture. And so on. So, the dependence of our moral<br />

judgments on different factors may show simply that moral truths

<strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism <strong>and</strong> <strong>Metaethical</strong> Objectivism 15<br />

depend on many factors, just as the movement of pool balls depends on<br />

the momentum of the cue impact, the surface of the table, the elasticity<br />

of the balls, <strong>and</strong> so on. But the multiplicity of factors does not count<br />

against the fact that all of the factors contribute to an ontologically<br />

objective outcome.<br />

Here is my reply. First, the degree of disagreement counts. Pool players<br />

may differ over whether one or more of the balls will end up in the<br />

pockets, but the disagreements will be minor compared to moral<br />

disputes over distributive justice, punishment, affirmative action,<br />

suicide, <strong>and</strong> other moral questions. I am tempted to say that the<br />

disagreement between advocates of impartiality in moral obligation <strong>and</strong><br />

advocates of partiality for special others is categorical. This is evidence<br />

that things are far more disorderly at the deepest level. Second, in the<br />

nonmoral cases the range of dispute over relevant factors is much less.<br />

For example, if we are trying to predict the outcome of the break by<br />

relying on our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of physics, we will agree that the intention<br />

of the ball striker is irrelevant to predicting the outcome of the break.<br />

On the contrary, moralists perennially debate whether agents’ intentions<br />

are relevant to the assessment of the quality of their actions. Third,<br />

predictions in any part of physical theory will dovetail with predictions<br />

in the rest of physical theory much more than do moral judgments. For<br />

example, we may be impartialists between our two children, partialists<br />

when it comes to how we treat those two contrasted to strangers, but<br />

impartialists when we think of children in a global political context. We<br />

assume that the laws governing nonmoral phenomena, if not uniform<br />

throughout the cosmos, have nothing like this sort of variation.<br />

7 Overview of the book<br />

In chapter 2, I explicate <strong>and</strong> justify two requirements for moral theories<br />

that would purport to be <strong>metaethical</strong>ly objective: soundness (providing<br />

only true moral judgments) <strong>and</strong> completeness (answering the whatshould-we-do-question<br />

for the entire range of moral questions). I show<br />

how these requirements flow from Worldview metaphilosophy <strong>and</strong> the<br />

intermediate-level methodological principles that I endorse in this<br />

chapter. In chapter 3, I argue that subjectivist metaphysical theories<br />

need not provide semantic analyses of moral language nor try to ‘find a<br />

place for reason’ in moral disputes. In chapter 4, I defend the crucial<br />

role I assign to moral intuitions in this book. In chapter 5, I argue that<br />

any sound <strong>and</strong> complete theory of moral obligation must be committed<br />

to impartiality rather than partiality. In chapter 6, I argue against the<br />

claim of the previous chapter by citing many examples in which<br />

impartiality is not morally required. I thereby give reason to think that

16 <strong>Metaethical</strong> Subjectivism<br />

our best-considered moral intuitions regarding impartiality contradict<br />

each other. In chapter 7, I argue that familiar deontological objections<br />

to consequentialist theories of moral obligation can be used, with<br />

considerable force, against any robust moral theory. Thus, deontological<br />

theories carry the seeds of their own demise, as well as those of all<br />

other moral theories. In chapter 8, I demonstrate the fragmentation that<br />

occurs when we try to decide what we should do, all things considered, if<br />

we holistically take into account theories of moral obligation, intrinsic<br />

value, <strong>and</strong> character virtues. I take this fragmentation as a third<br />

argument against thinking that moral theories can be sound <strong>and</strong><br />

complete. In chapter 9, I conclude that adopting <strong>metaethical</strong><br />

<strong>subjectivism</strong> can be preferable to adopting <strong>objectivism</strong> for the purposes<br />

of constructing (mostly) acceptable theories of normative ethics <strong>and</strong><br />

from the st<strong>and</strong>point of moral practice.