Nicolai RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908) Peter TCHAIKOVSKY ...

Nicolai RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908) Peter TCHAIKOVSKY ...

Nicolai RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908) Peter TCHAIKOVSKY ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Guild GmbH<br />

Switzerland<br />

GHCD 2391<br />

2012 Guild GmbH<br />

© 2012 Guild GmbH<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

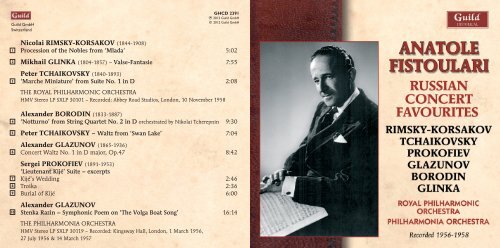

<strong>Nicolai</strong> <strong>RIMSKY</strong>-<strong>KORSAKOV</strong> (<strong>1844</strong>-<strong>1908</strong>)<br />

Procession of the Nobles from ‘Mlada’ 5:02<br />

Mikhail GLINKA (1804-1857) – Valse-Fantasie 7:55<br />

<strong>Peter</strong> <strong>TCHAIKOVSKY</strong> (1840-1893)<br />

‘Marche Miniature’ from Suite No. 1 in D 2:08<br />

THE ROYAL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA<br />

HMV Stereo LP SXLP 30101 – Recorded: Abbey Road Studios, London, 10 November 1958<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Alexander BORODIN (1833-1887)<br />

‘Notturno’ from String Quartet No. 2 in D orchestrated by Nikolai Tcherepnin 9:30<br />

<strong>Peter</strong> <strong>TCHAIKOVSKY</strong> – Waltz from ‘Swan Lake’ 7:04<br />

Alexander GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)<br />

Concert Waltz No. 1 in D major, Op.47 8:42<br />

Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)<br />

‘Lieutenant Kijé’ Suite – excerpts<br />

Kijé’s Wedding 2:46<br />

Troika 2:36<br />

Burial of Kijé 6:00<br />

Alexander GLAZUNOV<br />

Stenka Razin – Symphonic Poem on ‘The Volga Boat Song’ 16:14<br />

THE PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA<br />

HMV Stereo LP SXLP 30119 – Recorded: Kingsway Hall, London, 1 March 1956,<br />

27 July 1956 & 14 March 1957

A GUILD HISTORICAL RELEASE<br />

• Master source: Records from the collection of Edward Johnson<br />

• Remastering from original LPs: <strong>Peter</strong> Reynolds<br />

• Final master preparation: Reynolds Mastering, Colchester, England<br />

• Design: Paul Brooks, Design and Print, Oxford<br />

• Photo of Anatole Fistoulari courtesy of the Tully Potter Collection<br />

• Art direction: Guild GmbH<br />

• Executive co-ordination: Guild GmbH<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

Guild GmbH, Moskau 314b, 8262 Ramsen, Switzerland<br />

Tel: +41 (0) 52 742 85 00 Fax: +41 (0) 52 742 85 09 (Head Office)<br />

Guild GmbH, PO Box 5092, Colchester, Essex CO1 1FN, Great Britain<br />

e-mail: info@guildmusic.com World WideWeb-Site: http://www.guildmusic.com<br />

WARNING: Copyright subsists in all recordings under this label. Any unauthorised broadcasting, public<br />

performance, copying or re-recording thereof in any manner whatsoever will constitute an infringement of such<br />

copyright. In the United Kingdom licences for the use of recordings for public performance may be obtained from<br />

Phonographic Performances Ltd., 1 Upper James Street, London W1F 9EE.

and, truth to tell, thoughtless or unprepared performances, the playing of this immortal music is<br />

one of the highlights of this collection. Fistoulari here brings a lifetime’s experience as a conductor<br />

of his compatriot’s music (from the age of seven, be it remembered) and of ballets in the theatre.<br />

The conductor’s pacing and shaping of the music constitute an object-lesson to later conductors as<br />

to how this music should be performed.<br />

Alexander Glazunov’s Concert Waltz No 1 (in D major, Opus 47, 1893) is the first of two<br />

works in this collection by this rather neglected composer (1865-1936). It is another masterly<br />

interpretation by Fistoulari – recorded at the same sessions as the Tchaikovsky Waltz – receiving<br />

arguably the finest account it has ever enjoyed on disc. Glazunov’s Second Concert Waltz in F major<br />

followed a year later, but is even less frequently heard than its predecessor. The Philharmonia play the<br />

First Concert Waltz superbly well, as they do in just three movements from Prokofiev’s ‘Lieutenant<br />

Kijé’ Suite of 1934, taken from film music. The story goes that the character of Lieutenant Kijé was<br />

invented to placate a mistaken Russian ruler: at the end of the story, of course, the character has to<br />

be killed off by the courtiers – hence the concluding ‘Burial of Kijé’ – and Prokofiev’s score, quoting<br />

echt-Russian folk music and brilliantly orchestrated, has become a perennial concert favourite.<br />

Finally, the largest work in the programme is Glazunov’s symphonic poem ‘Stenka Razin’ – also<br />

full of familiar Russian folk tunes (familiar perhaps from their use by other Russian composers)<br />

– which was written in 1885 (when Glazunov was just 20, yet already a fully accomplished and<br />

established composer). The scope of this work reveals Fistoulari’s mastery at controlling larger<br />

musical canvases; the work is based on the life of a genuine Russian hero of the 17th-century<br />

(hence the folk-music element) and is a splendid evocation of both dramatic and lyrical expression,<br />

making a fitting end with the Philharmonia at their finest in this tribute to an outstanding Russian<br />

conductor.<br />

© Robert Matthew-Walker, 2012<br />

6<br />

It is with pleasure that Guild presents this programme of Russian Concert Favourites conducted<br />

by Anatole Fistoulari, the Russian-born, naturalised British conductor who was one of the most<br />

recorded and widely-admired masters of the baton in the decades following World War II, yet<br />

whose reputation, since his death in 1995 at the age of 88, has tended to become overlooked.<br />

Fistoulari was born in Kiev, where his father (who was a pupil both of Rimsky-Korsakov and of<br />

Anton Rubinstein) was a noted conductor. It was evident from a very young age that Anatole had<br />

inherited his father’s qualities, for the boy conducted his first orchestra at the astonishingly early age<br />

of seven – in Tchaikovsky’s ‘Pathètique’ Symphony. One must remember that this work had been<br />

heard for the first time just 23 years previously, conducted by the composer, and that orchestral<br />

recordings (which would have made it easier for any conductor – particularly a child, as Fistoulari<br />

was at the time – to have memorised the score) were, in 1914, in their infancy: certainly, the boy had<br />

to learn the work from the published score.<br />

From that concert, it would seem that Fistoulari’s lifetime’s career was settled. Following the<br />

1917 Revolution (at that time, he was still just ten years old), just three years later he found himself<br />

doubtless the youngest member of the growing émigré Russian musical colony in Paris, coming into<br />

contact with Stravinsky, Serge Koussevitzky, Alexander Tcherepnin, Serge Prokofiev and others,<br />

as well as having – at the age of 13, and on George Enescu’s recommendation – conducted Saint-<br />

Saëns’s opera ‘Samson et Dalilah’ in Bucharest.<br />

Another famous Russian with whom Fistoulari worked later in Paris was the great bass Feodor<br />

Chaliapin, who considered the conductor (then in his early- to mid-20s) to be an admirable partner;<br />

doubtless Chaliapin’s endorsement notably advanced Fistoulari’s reputation as a musician with an<br />

uncanny ability to follow a soloist – vocal or instrumental. Nor was this confined to performing<br />

musicians: the Russian connection in Paris did Fistoulari no harm at all. He soon carved out a name<br />

for himself as a much-admired conductor of ballet, fulfilling the report and prediction of a leading<br />

St <strong>Peter</strong>sburg critic, who wrote, after one of Fistoulari’s boyhood concerts, that he possessed an<br />

‘’Uncanny memory, extraordinary rhythmic sense and overpowering will, unknown in a child of his<br />

age, [which] make him an entire master of the orchestra - these are the qualities that give a promise<br />

of this child becoming a truly great master.’’<br />

3

Fistoulari conducted the Ballets Russes in Paris and on tour (including one to the United<br />

States) and he appeared in symphonic concerts in Germany and in Holland. But when World<br />

War II broke out in September 1939 Fistoulari volunteered for the French Army; following the<br />

capitulation after the German invasion in 1940 he escaped to England, where he met and, in 1942,<br />

married Anna Mahler, the only surviving daughter of Gustav Mahler (by whom he had a daughter,<br />

Marina, in 1943). That same year, 1943, Fistoulari was appointed principal conductor of the London<br />

Philharmonic Orchestra with a contract for 120 concerts - an average of one concert every three<br />

days.<br />

The pressure proved too much for conductor and orchestra, but after the war ended in 1945<br />

Fistoulari’s recording career expanded greatly over the following twenty years or so, which saw<br />

him making many records for EMI and Decca especially, perhaps most notably of ballet music.<br />

Although he was a much-admired accompanist in concerto recordings and of singers, he never<br />

recorded a complete opera, although he conducted several in New York.<br />

Fistoulari’s technique and knowledge of the Russian repertoire especially were legendary;<br />

in 1956 he conducted the London Philharmonic on a tour of the USSR, but he never obtained a<br />

permanent post with a major orchestra after World War II. None the less, his memory remained<br />

prodigious, even into old age, and although he never mastered a full command of the English<br />

language, he was always able to make himself understood, as the present writer remembers vividly,<br />

on producing what proved to be Fistoulari’s last recordings in 1978.<br />

These were of Violin Concertos by Tchaikovsky, Mendelssohn and Bruch, with the Philharmonia<br />

Orchestra accompanying the fine Japanese violinist Takayoshi Wanami. Fistoulari was particularly<br />

solicitous towards the soloist, who was born blind in 1945. These recordings, made for the Japanese<br />

Trio label, were first issued in Japan on two 12” LPs. It is a matter of no little regret that Fistoulari<br />

never recorded the one Russian work which, above all, he wished to commit to posterity through<br />

his interpretation: Rachmaninoff ’s Second Symphony, but we may judge in the collection of Russian<br />

pieces on this CD his mastery in the music which, above all, meant the most to him.<br />

Nor are the pieces in this collection entirely those which one might first think of in terms of<br />

‘Russian Concert Favourites’ today – although for Russian audiences all of this music would be<br />

familiar. None the less, we open with a simply magnificent performance of the ‘Procession of the<br />

Nobles’ from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera ‘Mlada’ (the opera dating from 1890; the story concerned<br />

with the coming of civilisation to relatively primitive Slavic regions). The music under Fistoulari<br />

is quite thrilling, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (still, at the time this recording was made,<br />

appearing under Sir Thomas Beecham, the Orchestra’s founder). The instrumental playing here<br />

is beyond reproach, but what is so consistently impressive is the tempo at which Fistoulari begins<br />

and maintains this unforgettable music – stately and inherently noble, as befits the character of<br />

the processional. The RPO is also featured in the rarely heard (for our time) Valse-Fantasie by<br />

Glinka – a work that exists in several versions (originally composed for piano in 1839), but here<br />

performed in the later version for full orchestra. It is a fascinating precursor of the immortal waltzes<br />

of Tchaikovsky (of which more anon), but again we can appreciate Fistoulari’s approach – content<br />

to let the music speak at its own pace, without underlining that which is already italicised. The first<br />

genuine piece by Tchaikovsky in this collection is another rarity: the Miniature March from his First<br />

Suite for Orchestra Opus 43, dating from 1879, a most attractive little piece in D minor, so expertly<br />

played by the Royal Philharmonic.<br />

The remaining music on this CD is played by the Philharmonia Orchestra, and again the music,<br />

with just one exception perhaps, is not so often heard in the versions Fistoulari had chosen. The<br />

first of the Philharmonia items is the ‘Nocturne’ movement from Borodin’s Second String Quartet<br />

(1881). This music is often heard in the string orchestra arrangement by Sir Malcolm Sargent but<br />

here we have what is believed to be the world premiere recording of the version for full orchestra by<br />

Nikolai Tcherepnin (1873-1945), father of the previously-mentioned Alexander Tcherepnin. There<br />

is no doubt that Fistoulari knew father and son in Paris (to where the family had moved in the early<br />

1920s) and his inclusion of Nikolai’s rarely-heard orchestration of the famous Nocturne was made<br />

in tribute to his colleague’s father.<br />

The most famous work in this collection is undoubtedly the Waltz from Tchaikovsky’s great<br />

four-act ballet ‘Swan Lake’, which appeared in 1875 following a commission from Vladimir<br />

Petrovich Begichev, who was then intendant of the Russian Imperial Theatres in Moscow. Although<br />

the waltz is one of those world-famous pieces which has suffered from multifarious arrangements<br />

4 5