Booklet

Booklet

Booklet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Guild GmbH<br />

Switzerland<br />

GHCD 2395<br />

2013 Guild GmbH<br />

© 2013 Guild GmbH<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

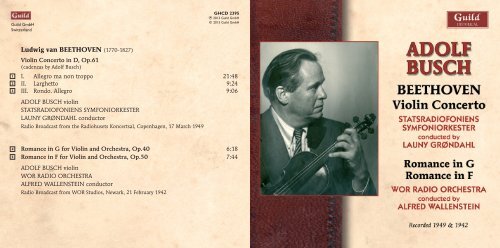

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)<br />

Violin Concerto in D, Op.61<br />

(cadenzas by Adolf Busch)<br />

I. Allegro ma non troppo 21:48<br />

II. Larghetto 9:24<br />

III. Rondo. Allegro 9:06<br />

ADOLF BUSCH violin<br />

STATSRADIOFONIENS SYMFONIORKESTER<br />

LAUNY GRØNDAHL conductor<br />

Radio Broadcast from the Radiohusets Koncertsal, Copenhagen, 17 March 1949<br />

4<br />

5<br />

Romance in G for Violin and Orchestra, Op.40 6:18<br />

Romance in F for Violin and Orchestra, Op.50 7:44<br />

ADOLF BUSCH violin<br />

WOR RADIO ORCHESTRA<br />

ALFRED WALLENSTEIN conductor<br />

Radio Broadcast from WOR Studios, Newark, 21 February 1942

A GUILD HISTORICAL RELEASE<br />

• Master source: tapes from the collection of Tully Potter and of the BrüderBuschArchiv<br />

in the Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe<br />

• Remastering: Peter Reynolds<br />

• Editing of the Violin Concerto: Antony Hodgson<br />

• Final master preparation: Reynolds Mastering, Colchester, England<br />

• Photos of Launy Grøndahl and Alfred Wallenstein courtesy of The Tully Potter Collection<br />

• Design: Paul Brooks, Design and Print, Oxford<br />

• Repertoire advisor: Dr. Jürgen Schaarwächter, Max-Reger-Institut with BrüderBuschArchiv, Karlsruhe<br />

• Art direction: Guild GmbH<br />

• Executive co-ordination: Guild GmbH<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

Guild GmbH, Moskau 314b, 8262 Ramsen, Switzerland<br />

Tel: +41 (0) 52 742 85 00 Fax: +41 (0) 52 742 85 09 (Head Office)<br />

Guild GmbH, PO Box 5092, Colchester, Essex CO1 1FN, Great Britain<br />

e-mail: info@guildmusic.com World WideWeb-Site: http://www.guildmusic.com<br />

LAUNY GRØNDAHL<br />

ALFRED WALLENSTEIN<br />

WARNING: Copyright subsists in all recordings under this label. Any unauthorised broadcasting, public<br />

performance, copying or re-recording thereof in any manner whatsoever will constitute an infringement of such<br />

copyright. In the United Kingdom licences for the use of recordings for public performance may be obtained from<br />

Phonographic Performances Ltd., 1 Upper James Street, London W1F 9EE.

had to be changed, several bars of music were missed, although all of Busch’s cadenzas were captured.<br />

At the present writer’s suggestion, the record producer Antony Hodgson has inserted passages from the<br />

1942 studio recording to fill the holes. Although it will be apparent to a keen listener where the five gaps<br />

come, this stratagem does at least allow us to hear the 1949 performance straight through. As for Busch’s<br />

interpretation, there is no obvious point-making in the first movement, even in the G minor episode, but<br />

this violinist has a way of getting under the skin of the music without departing from Classical principles.<br />

As in his performances of the late Beethoven quartets, Busch with his legendary long bow strokes can<br />

weight a simple legato line with significance, intensity and spirituality. The Larghetto, which for many<br />

players is no more than an intermezzo, is the heart of the Busch reading: Beethoven’s instruction ‘dolce’<br />

brings rapt concentration, rather than mere sweetness, and in the passage marked to be played on the two<br />

lower strings – where Leonid Kogan and Yehudi Menuhin were always at their best – Busch seems to move<br />

into another world. The finale, in which Busch and Grøndahl create something more substantial than usual<br />

without compromising Beethoven’s bucolic frolic, delights with springy rhythm and spontaneous touches.<br />

In the very month of his New York performances, February 1942, Busch recorded both Beethoven<br />

Romances for the WOR radio station in New York. The orchestra was the station’s own and the conductor<br />

was the WOR director of music, the former cellist Alfred Wallenstein. Although these pieces are not the<br />

equal of the Larghetto in the Concerto, they are very pleasing and satisfying in the hands of a master.<br />

Busch used to play them a good deal before the war – one or other of them would often be included in<br />

his marathon concerto programmes – and he had the full measure of them. His interpretations, utterly<br />

unsentimental, are admirable examples of his superb rhythmic control in slower music, and his haunting<br />

tone is here heard at its best.<br />

© Tully Potter, 2012<br />

6<br />

The Beethoven Concerto was the work that the great German violinist Adolf Busch played more often<br />

than any other. At least 400 concert performances are documented; and in 1927, the composer’s<br />

centenary year, he aired his interpretation more than 50 times, not counting the public rehearsals<br />

which were the rule in those days. In 1931 he played it five times under Arturo Toscanini’s baton in the<br />

United States. In all there were six collaborations with Toscanini, at least four with Mengelberg, at least two<br />

with Furtwängler and performances with virtually every other renowned conductor of Busch’s era: Walter,<br />

Weingartner, Muck, Monteux, Krauss, Scherchen, Boult, Wood, Barbirolli, Klemperer and his own elder<br />

brother Fritz. Perhaps the most dramatic was the final one with Toscanini, given at short notice during<br />

the 1939 Lucerne Festival. Bruno Walter, due to direct Mozart’s D minor Concerto from the keyboard<br />

and conduct Mahler’s Second Symphony, was engulfed by a family tragedy and so as not to disappoint the<br />

public, Toscanini and Busch laid on an all-Beethoven programme. The composer Samuel Barber described<br />

Busch’s contribution as ‘the most beautiful performance of the Beethoven Concerto I have ever heard’.<br />

Adolf Busch was born – on 8 August 1891 in Siegen, Westphalia – into a milieu in which everyone<br />

knew his or her place, the old Germany, recently unified by Bismarck but unchanged in its social<br />

conventions for centuries. Coming from a poor background, the Busch brothers had to work for everything<br />

they had. Pianist-conductor Fritz and cellist Herman shared Adolf ’s passion for music: playing with their<br />

father’s ensemble in clubs, bars and other dives was always fun for them, even if it was exhausting (Joseph<br />

Joachim, with whom Adolf was frequently compared, had the same attitude and would make music<br />

morning and night if he could). The adult Adolf Busch would often, in those non-union days, sit in with<br />

the orchestra for a symphony after playing a concerto. On one occasion, having performed Harold in Italy<br />

under Walter, he took the viola obbligato in the Reger edition of Wolf ’s Italian Serenade. He would not have<br />

understood the world-weary, cynical attitude of some modern musicians. He had little formal education<br />

but during his time at the Cologne Conservatory (1902-09) encountered many cultured people who helped<br />

him to educate himself. They included his violin teachers Willy Hess and Bram Eldering, both Joachim<br />

pupils; his composition teacher Fritz Steinbach, Brahms’s favourite conductor; his future father-in-law<br />

Hugo Grüters, director of music in Bonn; and the composer Max Reger, who was astonished when the<br />

17-year-old Busch played his hour-long concerto to him from memory.<br />

Busch chose the Brahms Concerto for his important early débuts and was already two years into his<br />

career when he essayed his first major performance of the Beethoven, in Vienna on 17 October 1911 with<br />

his mentor Steinbach conducting: afterwards he was called back to the platform eight times. On 7 February<br />

3

1912 he played it under Reger’s direction in Pforzheim, with the touring Meiningen Court Orchestra.<br />

His fiancée Frieda Grüters wrote home: ‘Reger told me Adolf is taking the place of Joachim; he has never<br />

heard the Concerto played in such a way.’ On 28 October 1912 Busch gave his first London rendering of<br />

the Concerto, with the LSO under Steinbach, again to acclaim; and from then on he was recognised as the<br />

work’s finest exponent. Early in 1913, as the new leader of the Konzertverein Orchestra (and its quartet),<br />

he mesmerised the Viennese audience and conductor Walter with his solo in the ‘Benedictus’ of the Missa<br />

solemnis. During the Great War, from his base in Vienna, Busch continued to tour the countries open to<br />

him and consolidated his reputation in central Europe as soloist and quartet leader. When peace came he<br />

was called to Joachim’s old teaching post in Berlin and became the busiest musician of his eminence in the<br />

world, giving a concert almost every night. One evening it might be a concerto, the next a quartet recital,<br />

the next a sonata programme with his partner Rudolf Serkin. He used his earnings as a soloist to subsidise<br />

his chamber music and put on a dazzling array of repertoire in his recitals – duos, trios, quartets, quintets,<br />

sextets, septets, octets. He was a pioneer of the chamber orchestra revival, experimenting with pick-up<br />

groups as early as 1916, although not until 1935 did he lead the regular ensemble of friends and pupils<br />

with which he performed and recorded Bach and Mozart. His summers were spent in relaxation – walking<br />

and climbing were favourite pastimes – and in composition. When the crisis of 1933 came, he was on the<br />

books of three publishers, Simrock, Breitkopf und Härtel and Eulenburg.<br />

As early as 1927, seeing how things were going politically in Germany, Adolf and Frieda Busch moved<br />

to Basel with their little daughter Irene and Serkin, who though only 12 years younger was like a son to<br />

them (he later married Irene). When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Busch was affronted by the insults<br />

and injustices meted out to the Jews. After experiencing anti-Semitic demonstrations against Serkin and<br />

the boycott of Jewish shops in Berlin on 1 April, he called it a day. He would not return to Germany, even as<br />

a visitor, for another 16 years. At a stroke he halved his income, said farewell to real success as a composer<br />

and lost his most appreciative audiences. In 1938 he boycotted Italy, where he was hugely popular, for<br />

similar reasons. The move to the United States, where being a Herr Professor Doktor counted for nothing<br />

and there was anti-German feeling – due not just to the war but to the stranglehold an earlier generation<br />

of Austro-German musicians had exerted on American music – was traumatic for him. Little interest was<br />

shown in him as a soloist and he ended up touring the country with a conductorless chamber orchestra,<br />

similar to the one he had led in Europe. Even here he was a pioneer, performing Schütz, Gabrieli, Purcell,<br />

Corelli and Rameau alongside his beloved Bach and Mozart. His performances and recordings of Handel’s<br />

Concerti grossi were among his finest achievements. In 1950 he helped to found the Marlboro summer<br />

school in Vermont, which still flourishes. He died at nearby Guilford on 9 June 1952.<br />

The saga of efforts to record Adolf Busch in the Beethoven Concerto was frustrating. By the late 1920s<br />

HMV and Columbia were vying for a recording: the former suggested using the Zürich Tonhalle Orchestra<br />

under Volkmar Andreae, then in the spring of 1930 actually booked the LSO, but Busch’s agents (prompted<br />

by his wife) objected to his being put on the cheaper plum label when his pupil Yehudi Menuhin was on<br />

the red label. Busch’s boycott of Germany from 1933 removed one of the main markets for a recording and<br />

so the situation arose where the Beethoven Concerto was available from German fiddlers such as Georg<br />

Kulenkampff, Max Strub and Riele Queling but not from the master. After emigrating to the U.S. in 1939,<br />

Busch was ignored by RCA Victor, who had a reciprocal arrangement with his European label HMV; but<br />

he was courted by Columbia and once he was over a 1940 heart attack, he began recording with Serkin<br />

and his quartet. Early in 1942, Fritz Busch conducted the New York Philharmonic-Symphony in a series<br />

of concerts for the orchestra’s centennial season at Carnegie Hall, and Adolf was soloist in four. On 29<br />

and 30 January he introduced New Yorkers to the Reger Concerto, in his own manuscript reworking, but<br />

most critics rejected it. On 7 and 8 February the Busch brothers again collaborated with the Philharmonic-<br />

Symphony, in the Beethoven Concerto, Adolf airing a new set of cadenzas written the previous year. The<br />

Sunday-afternoon CBS network broadcast was taken down by two home recordists and one of those<br />

documents has been released. It is an admirable corrective to the official Columbia recording, made<br />

next day at Liederkranz Hall. Unfortunately the production was delegated to the inexperienced Goddard<br />

Lieberson. Busch was palpably under strain in the opening movement, his nervousness exacerbated by<br />

Lieberson’s insisting he stand on a raised platform, which made him feel remote from his brother and the<br />

orchestra and brought him too close to the microphone. The resulting poor balance caused him to reject<br />

the recording, which was not issued until after his death. Had it been released at the time, it would have<br />

enhanced his reputation, as despite its faults it is one of the great readings of the Concerto.<br />

The frustration continued when, on 17 March 1949, Busch played the Concerto at the Radiohusets<br />

Koncertsal, Copenhagen, with the Danish State Radio Symphony Orchestra under Launy Grøndahl.<br />

The violinist was in terrific form, his big golden tone shining forth, and the orchestral musicians – with<br />

whom he was well acquainted from many visits to the Danish capital – gave him wholehearted support,<br />

as did their fine conductor. Sadly, Danish State Radio had not yet acquired tape recording facilities; and<br />

only one turntable was in operation for taking the performance down on discs: thus every time a disc<br />

4 5