Categorical vs. Gradient: What ... - The University of Texas at Austin

Categorical vs. Gradient: What ... - The University of Texas at Austin

Categorical vs. Gradient: What ... - The University of Texas at Austin

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>C<strong>at</strong>egorical</strong> <strong>vs</strong>. <strong>Gradient</strong>: <strong>Wh<strong>at</strong></strong> asl fingerspelling teaches us about the phonetics-phonology interface<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are many phonological phenomena th<strong>at</strong> have phonetic motiv<strong>at</strong>ions in spoken languages (e.g., word-final devoicing in<br />

German, flapping in English), but only a few such phenomena have been described for signed languages (sls). One is the use <strong>of</strong><br />

phonological word constituent boundaries to account for the assimil<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> selected fingers in compounds (Sandler and Lillo-<br />

Martin, 2006). In this paper st<strong>at</strong>istical methods typically used with larger corpora shed light on questions <strong>of</strong> the phoneticsphonology<br />

interface in sls, focusing on asl fingerspelling. Because fingerspelling involves rapid sequences <strong>of</strong> handshapes it is<br />

an ideal place to investig<strong>at</strong>e the phonetics and phonology <strong>of</strong> handshape (e.g., coarticul<strong>at</strong>ion, assimil<strong>at</strong>ion, as well as temporal<br />

overlap <strong>of</strong> articul<strong>at</strong>ory gestures). Additionally, these results contribute to general deb<strong>at</strong>es about the definition <strong>of</strong> phonetics and<br />

phonology (Ke<strong>at</strong>ing, 1996; Cohn, 1998). This paper focuses on two types <strong>of</strong> co-articul<strong>at</strong>ory phenomena — ulnar digit extension<br />

(ude; 1 & figure 1) (Cheek, 2001; Hoopes, 1998; Jerde et al., 2003; Tyrone et al., 2010), and ulnar digit flexion (udf; 2 & figure<br />

2) — to demonstr<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> by looking <strong>at</strong> the variability and distribution <strong>of</strong> such behaviors in detail we can better understand<br />

the differences between phonetics and phonology <strong>of</strong> sls. ude and udf provide us with two inform<strong>at</strong>ive case studies in this<br />

regard. A new phonological oper<strong>at</strong>ion is also described in the paper and <strong>at</strong>tributed to Underspecific<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>The</strong>ory.<br />

Method We recorded nearly 3 hours <strong>of</strong> 2 n<strong>at</strong>ive asl signers fingerspelling a total <strong>of</strong> 2,400 words, which included names,<br />

nouns, and foreign words between 5 and 15 letters. Every target letter was tagged, labeled, and annot<strong>at</strong>ed for ude and udf<br />

— approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 8,000 handshapes were coded in all and used for both analyses below. <strong>The</strong> steps <strong>of</strong> transcription included<br />

human coding, algorithmic averaging, forced alignment, and verific<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

Analysis Using multilevel logistic regressions both ude and udf show significant main effects for signer (1, 2), word type<br />

(noun, name, foreign), and environment (previous, following). Moreover, segment fusion may occur in ude when the selected<br />

fingers <strong>of</strong> adjacent handshapes are completely distinct, such as -t- (thumb and index finger selected) and -i- (pinky finger<br />

selected), as in a-c-t-i-v-[it]-y. <strong>The</strong>se phonetic effects will elabor<strong>at</strong>ed upon in the talk.<br />

In addition to these phonetic effects, we found th<strong>at</strong> not all handshapes are equally likely to trigger ude, and not all targets are<br />

equally likely to undergo udf. Our analysis for why -e- and -o- are the two handshapes most susceptible to udf involves Underspecific<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>The</strong>ory. In the Prosodic Model Brentari (1998) these two handshapes have unspecified values for the selected<br />

fingers and we argue th<strong>at</strong> it is this fact th<strong>at</strong> facilit<strong>at</strong>es the assimil<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> neighboring values.<br />

Conclusions <strong>The</strong> phenomena explored in this paper seem to be on either side <strong>of</strong> the boundary between phonetics and<br />

phonology <strong>of</strong> handshape: ude is temporally gradient, and does not need to refer to abstract phonological fe<strong>at</strong>ures. Whereas<br />

udf does not appear to be temporally gradient, and is most easily described by positing assimil<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> an abstract phonological<br />

fe<strong>at</strong>ure (i.e., selected finger quantity).<br />

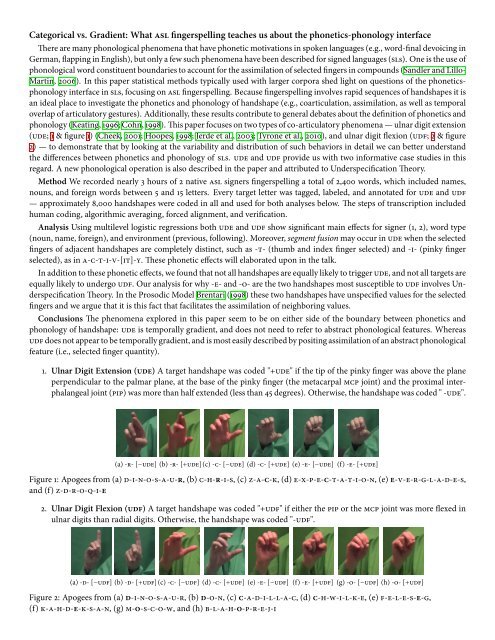

1. Ulnar Digit Extension (ude) A target handshape was coded "+ude" if the tip <strong>of</strong> the pinky finger was above the plane<br />

perpendicular to the palmar plane, <strong>at</strong> the base <strong>of</strong> the pinky finger (the metacarpal mcp joint) and the proximal interphalangeal<br />

joint (pip) was more than half extended (less than 45 degrees). Otherwise, the handshape was coded " -ude".<br />

(a) -r- [−ude] (b) -r- [+ude](c) -c- [−ude] (d) -c- [+ude] (e) -e- [−ude] (f) -e- [+ude]<br />

Figure 1: Apogees from (a) d-i-n-o-s-a-u-r, (b) c-h-r-i-s, (c) z-a-c-k, (d) e-x-p-e-c-t-a-t-i-o-n, (e) e-v-e-r-g-l-a-d-e-s,<br />

and (f) z-d-r-o-q-i-e<br />

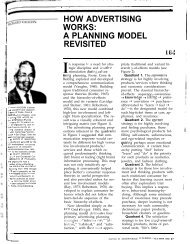

2. Ulnar Digit Flexion (udf) A target handshape was coded "+udf" if either the pip or the mcp joint was more flexed in<br />

ulnar digits than radial digits. Otherwise, the handshape was coded "-udf".<br />

(a) -d- [−udf] (b) -d- [+udf](c) -c- [−udf] (d) -c- [+udf] (e) -e- [−udf] (f) -e- [+udf] (g) -o- [−udf] (h) -o- [+udf]<br />

Figure 2: Apogees from (a) d-i-n-o-s-a-u-r, (b) d-o-n, (c) c-a-d-i-l-l-a-c, (d) c-h-w-i-l-k-e, (e) f-e-l-e-s-e-g,<br />

(f) k-a-h-d-e-k-s-a-n, (g) m-o-s-c-o-w, and (h) b-l-a-h-o-p-r-e-j-i

References<br />

Brentari, D. (1998). A prosodic model <strong>of</strong> sign language phonology. <strong>The</strong> MIT Press.<br />

Cheek, D. A. (2001). <strong>The</strong> Phonetics and Phonology <strong>of</strong> Handshape in American Sign Language. PhD thesis, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Texas</strong><br />

<strong>at</strong> <strong>Austin</strong>.<br />

Cohn, A. C. (1998). <strong>The</strong> phonetics-phonology interface revisited: Where’s phonetics? In <strong>Texas</strong> Linguistic Forum, volume 41,<br />

pages 25–40. <strong>Austin</strong>; <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Texas</strong>; 1998.<br />

Hoopes, R. (1998). A preliminary examin<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> pinky extension: Suggestions regarding its occurrence, constraints, and<br />

function. Pinky extension and eye gaze: Language use in Deaf communities, pages 3–17.<br />

Jerde, T. E., Soechting, J. F., and Flanders, M. (2003). Coarticul<strong>at</strong>ion in fluent fingerspelling. Journal <strong>of</strong> Neuroscience,<br />

23(6):2383–2393.<br />

Ke<strong>at</strong>ing, P. A. (1996). Working Papers in Phonetics, chapter <strong>The</strong> Phonology-Phonetics Interface, pages 45–60. Number 92 in<br />

Working Papers in Phonetics, Department <strong>of</strong> Linguistics. Department <strong>of</strong> Linguistics, ucla, Los Angeles.<br />

Sandler, W. and Lillo-Martin, D. (2006). Sign language and linguistic universals. Cambridge Univ Press.<br />

Tyrone, M. E., Nam, H., Saltzman, E. L., M<strong>at</strong>hur, G., and Goldstein, L. (2010). Prosody and movement in american sign<br />

language: A task-dynamics approach. In Speech Prosody 2010, pages 1–4.<br />

2