English - IFAD

English - IFAD

English - IFAD

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ASSETS AND THE RURAL POOR<br />

locked into inefficient modes of ownership; but<br />

some land reform has taken place.<br />

Reform experience confirms the greater efficiency<br />

of small farms (Box 3.4). Redistributing<br />

farmland control to poor families (a) relieves<br />

poverty because their income from farming rises,<br />

and because they hire more labour per hectare<br />

from other poor families; (b) gives the poor property<br />

rights incentives to investment and management;<br />

and (c) increases yields (and often total factor<br />

productivity) by shifting land to people with<br />

lower transaction costs in screening, applying and<br />

supervising both family and hired labour.<br />

Thus, well-conducted land redistribution can<br />

both favour efficiency and reduce rural poverty.<br />

Lieten 28 argues that land reform in West Bengal<br />

triggered faster growth and poverty reduction,<br />

from 52% in 1978 to 28% in 1988; improved efficiency<br />

of irrigation required prior equalization in<br />

the agrarian system. Besley and Burgess 29 show<br />

that Indian States with more land reform also<br />

later achieved faster poverty reduction. Tyler et<br />

al. 30 show that countries with more equal land<br />

enjoyed faster agricultural growth. We have seen<br />

that economic growth tends to be sluggish in very<br />

unequal countries, probably mainly because<br />

excluding large proportions of people from access<br />

to land and human capital is inefficient.<br />

Today, land reform has returned to national and<br />

international agendas, as seen in the international<br />

summits and agreements of the 1990s. Land reform<br />

is a central pillar of, amongst others, the UN<br />

Commission on Sustainable Development, the<br />

World Food Summit, the Convention to Combat<br />

Desertification and the Convention on Biological<br />

Diversity. Each of these events has been informed<br />

by the challenges and difficulties experienced in the<br />

past ranging from (a) redistributed land to the nonpoor;<br />

(b) failure to identify, train or support beneficiaries<br />

committed to farming; (c) lack of mechanisms<br />

to resolve conflicts and address complex<br />

situations such as civil strife and land invasions;<br />

(d) confiscation without compensation; (e) topdown<br />

state-led reform; or (f) forced collectivization.<br />

The 1980s saw progress in Iran, Nicaragua and<br />

El Salvador. In the 1990s reform moved on to the<br />

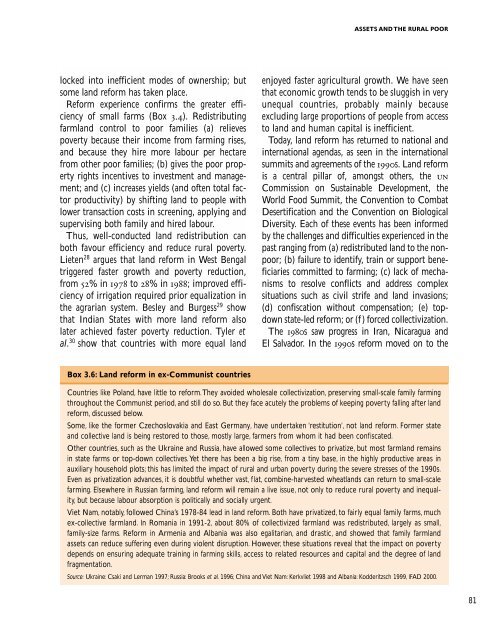

Box 3.6: Land reform in ex-Communist countries<br />

Countries like Poland, have little to reform.They avoided wholesale collectivization, preserving small-scale family farming<br />

throughout the Communist period, and still do so. But they face acutely the problems of keeping poverty falling after land<br />

reform, discussed below.<br />

Some, like the former Czechoslovakia and East Germany, have undertaken ‘restitution’, not land reform. Former state<br />

and collective land is being restored to those, mostly large, farmers from whom it had been confiscated.<br />

Other countries, such as the Ukraine and Russia, have allowed some collectives to privatize, but most farmland remains<br />

in state farms or top-down collectives.Yet there has been a big rise, from a tiny base, in the highly productive areas in<br />

auxiliary household plots; this has limited the impact of rural and urban poverty during the severe stresses of the 1990s.<br />

Even as privatization advances, it is doubtful whether vast, flat, combine-harvested wheatlands can return to small-scale<br />

farming. Elsewhere in Russian farming, land reform will remain a live issue, not only to reduce rural poverty and inequality,<br />

but because labour absorption is politically and socially urgent.<br />

Viet Nam, notably, followed China’s 1978-84 lead in land reform. Both have privatized, to fairly equal family farms, much<br />

ex-collective farmland. In Romania in 1991-2, about 80% of collectivized farmland was redistributed, largely as small,<br />

family-size farms. Reform in Armenia and Albania was also egalitarian, and drastic, and showed that family farmland<br />

assets can reduce suffering even during violent disruption. However, these situations reveal that the impact on poverty<br />

depends on ensuring adequate training in farming skills, access to related resources and capital and the degree of land<br />

fragmentation.<br />

Source: Ukraine: Csaki and Lerman 1997; Russia: Brooks et al. 1996; China and Viet Nam: Kerkvliet 1998 and Albania: Kodderitzsch 1999, <strong>IFAD</strong> 2000.<br />

81