mishqui-yacu, sweet water - IFAD

mishqui-yacu, sweet water - IFAD

mishqui-yacu, sweet water - IFAD

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Ministry<br />

of Social<br />

Welfare<br />

Royal Embassy of<br />

The Netherlands in<br />

Ecuador<br />

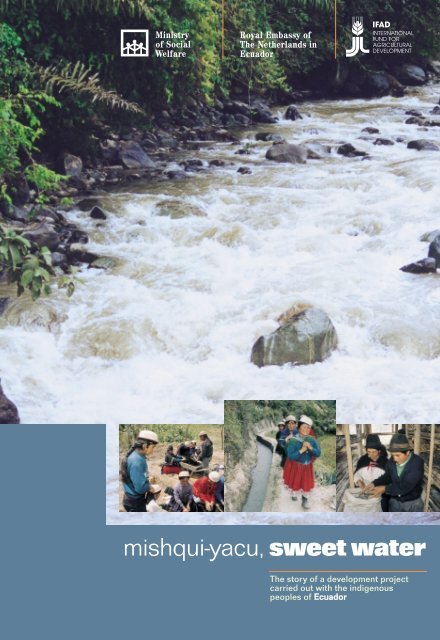

<strong>mishqui</strong>-<strong>yacu</strong>, <strong>sweet</strong> <strong>water</strong><br />

The story of a development project<br />

carried out with the indigenous<br />

peoples of Ecuador

<strong>mishqui</strong>-<strong>yacu</strong>, <strong>sweet</strong> <strong>water</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

3 Foreword<br />

5 Preface<br />

9 Presentation<br />

11 Introduction<br />

14 Ecuador: Reign of Contrasts<br />

14 The Highlands<br />

16 Thirst for Water in Hatun Cañar<br />

18 The Cañaris<br />

25 Mountains: Realm of Power<br />

26 Culebrillas: Where the Water Is Born<br />

30 Water and Development<br />

33 Cañari Development Initiatives<br />

35 The Initial Proposal<br />

38 Conflict!<br />

46 Local Patriotism<br />

50 The Huasipungo System<br />

52 Land Reforms<br />

55 Up from the Middle Ages<br />

56 Getting Organized<br />

60 The ‘Indian Question’ and the<br />

Rise of CONAIE<br />

64 UPCCC, CARC and<br />

Ethnic Politics in Cañar<br />

67 The Baseline Study<br />

70 Cholera and Drinking Water<br />

75 Credit<br />

75 Gender and Migration<br />

79 Politics and Renovation<br />

80 The Farmer Coordinator<br />

81 Irrigation<br />

87 The Mestizos?<br />

89 What Can We Learn from the<br />

CARC Project?<br />

94 Bibliography

© 2001 by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (<strong>IFAD</strong>)<br />

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression<br />

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Fund for Agricultural Development of the<br />

United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or<br />

concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations “developed” and “developing”<br />

economies are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement<br />

about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process.<br />

All rights reserved<br />

ISBN 92-9072-010-7<br />

Prepared by: Jan Lundius for the Latin America and the Caribbean<br />

Division of <strong>IFAD</strong>. Jan Lundius is an academic of Swedish nationality<br />

with a doctorate in Comparative Religion and with a specialization in<br />

the nature of religion in rural areas. We would like to thank Jan<br />

Lundius for giving us the opportunity to profit by his vast knowledge<br />

and creative ability in documenting experiences in rural development.<br />

Produced by: Publications Team of <strong>IFAD</strong><br />

Design: Silvia Persi<br />

All photos <strong>IFAD</strong><br />

Susan Beccio: pages 5, 6, 9, 11, 13, 17, 28, 32, 45, 51, 53, 57, 61, 63,<br />

69, 74, 78, 81 - Giuseppe Bizzarri: cover and pages 7, 25, 35, 37, 59,<br />

64, 72, 81, 82, 83, 85, 91, 93 - Jan Lundius: cover and pages 3, 20, 21,<br />

23, 27, 41, 42, 46, 55, 67, 69, 72, 77, 85, 87, 89, 91<br />

Printed by: GMS Grafiche - Rome, Italy<br />

April 2001<br />

Via del Serafico, 107 – 00142 Rome, Italy<br />

Tel.: +39-0654591 – Fax: +39-065043463<br />

E-mail: <strong>IFAD</strong>@<strong>IFAD</strong>.ORG - Web site: www.ifad.org

foreword<br />

Ecuador is a small country that straddles the equator, or the<br />

ecuador in Spanish. Its long beaches are just hours away from its high<br />

mountain peaks, which rise up only hours away from its lush forests,<br />

so rich in natural resources. In this book, Jan Lundius gives an objective<br />

description of nature’s generosity in Ecuador and its rich diversity<br />

of ethnic groups, each with its own customs. One of these groups is the<br />

Cañaris, the original inhabitants of the mountains and valleys of the<br />

southern highland region. The Cañaris have received support from the<br />

Government of Ecuador through <strong>IFAD</strong> financing of a rural development<br />

project that also included contributions from the Government of<br />

the Kingdom of The Netherlands. As the following chapters will note,<br />

it was not always an easy path; in fact, many hurdles had to be overcome<br />

but, in the end, will-power prevailed.<br />

The Cañaris – who are both the focus and the raison d’être of the<br />

project – of course hold their own views and from time to time have<br />

said “no” to mestizo technical staff who have wanted to do things for<br />

them rather than with them. The process ultimately was one of consensus<br />

involving joint decisions and joint work, and the presence of<br />

Rudolf Mulder and later Gauke Andriesse, both of The Netherlands,<br />

was of vital importance to the project’s success.<br />

Under the Agrarian Reform Act of 1963, the land was returned to its<br />

rightful owners: the indigenous communities. Although the process<br />

itself was fraught with inequities, this piece of legislation enshrined a<br />

historical act of sweeping proportions: it broke the chains that had<br />

bound indigenous people to landowners, thus bringing an end to a<br />

dark period in the country’s history.<br />

3<br />

[ The Cañari people said "no" ]

4<br />

This meant that many indigenous people were now owners of their<br />

own small lots (huasipungos). But the strong sunlight that shines<br />

down on this region of the world is counteracted by the lack of another<br />

crucial element: <strong>water</strong>. Indigenous residents and farmers alike have<br />

always had one eye on the field as they sowed their crops and the<br />

other on the sky, hopeful that clouds would soon appear to provide<br />

<strong>water</strong> to make their plants grow and to fill the cisterns for their family<br />

drinking <strong>water</strong>.<br />

The local Cañari organizations and mestizo farmers that had joined<br />

the project thus decided that the Upper Basin of the Cañar River<br />

Rural Development Project (CARC) should focus on the construction,<br />

rehabilitation and maintenance of irrigation canals and <strong>water</strong><br />

supply systems. The testimonials that follow speak eloquently of the<br />

overall process, including the problems encountered and how they<br />

were overcome.<br />

It was clear that start-up of the activities would need to be accompanied<br />

by training and the organization of <strong>water</strong> user boards to ensure<br />

rational <strong>water</strong> use and management, strengthening of organizations<br />

that benefit from irrigation canals, technical assistance and credit.<br />

These activities complement each other; if they are not carried out in<br />

a simultaneous and comprehensive fashion, the component is doomed<br />

to failure.<br />

This has not been an easy project; in fact, it has been a very complex<br />

one. The actors, however, have always had the integrity to keep<br />

moving ahead despite all the problems. In the final analysis, it may not<br />

be all that different from many other projects. What makes it different<br />

is the setting in which it has been carried out.<br />

Rafael Guerrero Burgos<br />

Undersecretary for Rural Development<br />

Ministry of Social Welfare

preface<br />

Aside from supporting the fight against poverty, what other<br />

motivation or specific orientation led The Netherlands Development<br />

Cooperation to cofinance, beginning in early 1992, the Upper Basin of<br />

the Cañar River Rural Development Project (CARC)?<br />

Land reform alone was obviously not the definitive solution to the<br />

problems of the rural poor in Cañar province. It was not enough just<br />

to have land to sow crops or graze livestock on, nor was it enough to<br />

hope for an "excellent" rainy season. The key would be <strong>water</strong> for irrigation,<br />

a very scarce resource.<br />

Accordingly, working with the International Fund for Agricultural<br />

Development (with support from the Andean Development Corporation<br />

and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture), the<br />

Ministry of Social Welfare (through its Undersecretariat for Rural<br />

Development) and various smaller-scale indigenous and farmer organizations,<br />

The Netherlands Development Cooperation lent support for<br />

implementation of the CARC project. The purpose of the project was<br />

to boost food self-sufficiency and in-come levels for rural poor in the<br />

area, mainly by increasing the availability of <strong>water</strong> through the construction<br />

or rehabilitation of irrigation systems and better on-farm<br />

management of <strong>water</strong>.<br />

Once it became clear that the ill-advised plan to build a dam on<br />

Lake Culebrillas had failed, the project was immediately reformulated.<br />

Priority was shifted from "irrigation systems" to "<strong>water</strong> management",<br />

following recommendations of the initial technical review mission<br />

and the findings of a baseline study (Rural Economy and<br />

Production Systems: A Baseline Study for the Andean Highlands<br />

5

6<br />

[Economía campesina y sistemas de producción, estudio de base de la<br />

sierra andina]. DHV Consultants BV, Quito, 1995). The study analysed<br />

all facets of the producer economy, described the region’s agroecology<br />

and helped to explain the existing interrelationships. It also contributed<br />

to the planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of<br />

the project and provided tools for training and technical assistance.<br />

The construction and rehabilitation of infrastructure, which included<br />

rural roads, was complemented with sustainable community-based<br />

management of forest resources, farm credit and legal advice for the<br />

organizations.<br />

Although start-up technically took place in 1996, the first tangible<br />

achievements did not appear until 1997, owing mainly to recurring<br />

political problems (government instability) and, to a certain degree,<br />

lack of local counterpart funding (economic and financial crisis).<br />

Working against a project completion horizon of 1999, a second<br />

technical review mission was sent to the field and concluded that,<br />

despite the relatively short time the project had been under implementation,<br />

some important achievements had been made in such<br />

areas as construction work and the strengthening of local organizations.<br />

Subcontracting to non-governmental organizations (e.g. for<br />

drinking <strong>water</strong> supply and credit) had been a key factor.<br />

On that basis, the project was extended through the end of 2000 in<br />

order to allow for completion of the physical infrastructure and the<br />

consolidation and transfer of its management. Other activities involved<br />

organized beneficiary groups (irrigation and <strong>water</strong> user boards)<br />

and other local organizations, and increased support for productive<br />

activities.<br />

[ Fair distribution of <strong>water</strong> ]

The strategy called for a gradual but significant scaling back of the<br />

project’s executing unit, while transferring responsibility for services<br />

to local organizations such as producer or <strong>water</strong> user associations and<br />

subcontracting to NGOs at least through 2001. These NGOs (consortia<br />

made up of CICDA-CEDIR and PROTOS-SENDAS) are overseeing the<br />

transfer, technical assistance and training activities that will promote<br />

the diversification of production and build post-harvest and marketing<br />

capacity among farmer organizations – as well as among farmers<br />

and their families – in the high-priority areas of El Tambo-Juncal and<br />

Suscal-Chontamarca.<br />

In other words, the last stage of the project aims to intensify the agricultural<br />

output of local production units by ensuring access to, control over<br />

and use of resources, services and infrastructure for production, irrigation<br />

and drinking <strong>water</strong>, as well as the strengthening of their organizations.<br />

The objectives are many: enhance the availability, control and fair<br />

distribution of <strong>water</strong> for irrigation and human consumption; have<br />

<strong>water</strong> user and irrigation boards assume responsibility for sustainable<br />

management of their systems (administration, operation and maintenance)<br />

and conflict resolution; diversify and intensify the agricultural<br />

output of production units; help producer groups to market products<br />

with greater added value, on a timely basis, through traditional or new<br />

marketing chains so as to enhance local production prices and foster<br />

new investment; achieve better gender balance by raising the profile<br />

and strengthening the leadership of women in producer associations<br />

and boards and ensure gender equity in access to project benefits; and<br />

systematize and disseminate the project’s experience by training professionals,<br />

technical specialists, rural residents and students in the<br />

value of <strong>water</strong> in productive systems.<br />

7

8<br />

There are at least three important lessons to be drawn from the<br />

years of work with this type of project. First, the factors of production<br />

(<strong>water</strong>, land, credit) cannot be approached in an isolated fashion; rather,<br />

they need to be complemented with other activities through-out<br />

the production chain and even in the marketing chain, as part of a<br />

long-term process. Second, the involvement of beneficiary organizations<br />

– in this case, irrigation and <strong>water</strong> user boards, producer associations,<br />

communities and smaller-scale organizations – is crucial to<br />

obtaining tangible, sustainable results, thus meshing and reconciling<br />

their initiatives and proposals with the support from NGOs, governmental<br />

agencies and international cooperation. Lastly, ethnic and cultural<br />

factors – in this case, of the Cañari group – must be taken into<br />

account in programming and implementation, especially if activities<br />

are to be sustainable.<br />

The Embassy of The Netherlands in Ecuador presents this publication<br />

as a testimony to the responsibility that was gratefully shared,<br />

despite the many issues it had to address with the numerous actors<br />

and stakeholders involved in the important task here described.<br />

Jan Bauer<br />

Environmental Affairs and<br />

Rural Development Specialist<br />

Royal Embassy of The Netherlands<br />

Quito, Ecuador

presentation<br />

I have known the Cañar project for more than ten years – since its<br />

development phase, which marked the beginning of <strong>IFAD</strong>'s attention<br />

to indigenous peoples in various Latin American countries. As can be<br />

seen in this publication, the history of indigenous peoples has gone<br />

through a series of dramatic historical stages. The year 1992 marked<br />

the 500th anniversary of the conquest of many of the lands belonging<br />

to indigenous peoples – and since then they have had to struggle for<br />

their rights, their land and respect for their culture.<br />

The Cañar project has been no exception to this history and the<br />

project went through a very tense and difficult initial phase. The project<br />

design paid insufficient attention to past history and the concerns<br />

of the various communities that should have been the leading actors<br />

in this activity. This was a hard lesson for us – equitable participation<br />

had not been adequately respected.<br />

In the second phase since 1995, local organizations and the project<br />

showed the fruits of close shoulder-to-shoulder collaboration. As a<br />

result, irrigators' boards were set up, and the confidence of the population<br />

was gained when a cholera epidemic was overcome. An<br />

unorthodox system was put in place ("Electric Water") for supplying<br />

drinking <strong>water</strong> to various communities, and of course the project<br />

facilitated the arrival of <strong>water</strong> to crops via irrigation systems.<br />

Having arrived at the end of this project, we would like to think about,<br />

listen to and reflect on the history of the Cañaris at various stages of<br />

their existence as well as bring together certain elements of what the<br />

Cañar project tried to support – greater access to <strong>water</strong>, improved<br />

organization and a more equitable society for men and women.<br />

9<br />

[ Shoulder–to–shoulder<br />

collaboration ]

10<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> considers that this project has been successful not so much<br />

for having reached all of its initially stated objectives, but because it<br />

left an inheritance in the hands of the El Tambo and Suscal communities<br />

that should enable them to improve the lives of their families in<br />

coming years and decades.<br />

We are very grateful to the Cañaris, their organizations, the Cañar<br />

project technical staff and to the NGOs CICDA-CEDIR, PROTOS and<br />

SENDAS – without them, it would not have been possible in such a<br />

short time, since 1997, to have achieved so much.<br />

I would also like to thank the Government of The Netherlands,<br />

which not only made a financial donation to the project, but also facilitated<br />

very crucial support to its implementation through the provision<br />

of experts and especially the codirectors.<br />

I would like to invite you to read this story of the Cañar project and<br />

of the Cañaris – do not expect a standard project completion report,<br />

nor a checklist of successes. However, I think that in this simple and<br />

open account the reader can appreciate the achievements of the Cañar<br />

communities, as well as the difficulties they overcame to attain them.<br />

Raquel Peña-Montenegro<br />

Director<br />

Latin America and the Caribbean Division<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>

introduction<br />

This is not a book about a project. Rather, it is a book about the people<br />

who live in an area where a development project was carried out.<br />

The Cañaris are one of Ecuador’s indigenous groups and in this book<br />

they have been given an opportunity to speak up and speak out about<br />

the <strong>IFAD</strong>-designed and supported CARC project: the impact it has had<br />

on their lives, how it has helped them, how it has opened their eyes to<br />

new opportunities, and how some of these opportunities have yet to be<br />

fully tapped.<br />

The story of the Cañaris is an important one and the CARC project<br />

is only a small part of that story (indeed, it is almost an entire story in<br />

and of itself). The history of the Cañaris is a story of the struggle for<br />

<strong>water</strong> (for irrigation) and of the peace and unity brought by <strong>water</strong> (for<br />

consumption). It is a story about lack of foresight stemming from precipitate<br />

action by well-meaning mestizos and Europeans and unfamiliarity<br />

with cañari history. But it is also a story that stands out, like the<br />

<strong>water</strong> pipes brought later by the mestizos to combat a cholera epidemic<br />

that threatened to decimate the Cañaris, and a story that highlights<br />

the importance of bottom-up organization among the project’s<br />

target population, who were able to effect change and transform a<br />

bureaucratic instrument into a form of democratic development that<br />

is pursued by consensus among area residents, consultants, officials of<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>, The Netherlands Cooperation and the national and local governments<br />

of Ecuador.<br />

The lessons learned from this experience point, once again, to the<br />

importance of organizations and “ownership” by project beneficiaries.<br />

11<br />

[<br />

A story of struggle<br />

and peace<br />

brought by <strong>water</strong> ]

12<br />

They underscore the positive impact of small-scale factors that lie<br />

within their control and contribute to making their activities sustainable.<br />

They also show the importance of open dialogue between organizations<br />

and between “inside” and “outside” stakeholders in the service<br />

of development.<br />

The CARC project teaches, once again, how a lack of familiarity with<br />

local traditions and customs, coupled with projects perceived as<br />

“monumental”, such as the attempt to build a dam on Lake<br />

Culebrillas, are neither the door nor the path to combat rural poverty.<br />

There are also some smaller lessons to be learned, on details such<br />

as credit, infrastructure, technical assistance and training, i.e. what<br />

worked and what did not. The most important lessons, however, were<br />

the crucial role of bottom-up organization, the dynamic role of rural<br />

women and the setting aside of ethnic and political divisions when a<br />

community and human lives are at stake.<br />

Fate (the appearance of a horrible disease) and the solutions<br />

devised to combat it lay at the root of the second period of Cañari history:<br />

development of the upper Cañar River basin.<br />

In this second period, a leading role was played by the men and<br />

women of The Netherlands Cooperation (especially Rudolf Mulder<br />

and Gauke Andriesse), the unflagging efforts of local officials – both<br />

indigenous and non-indigenous – and Ecuador’s Ministry of Social<br />

Welfare, and last but not least, the support of <strong>IFAD</strong> staff in Rome.<br />

The main part, however, has been played and continues to be played<br />

by the indigenous Cañari men and women and the organizations<br />

through which they decided to take their fate into their own hands. It<br />

is to them that we dedicate this book, which Jan Lundius has produced<br />

by weaving local voices in with interviews and study findings. We hope<br />

that this story will allow readers that are unfamiliar with the CARC project<br />

area to gain a fuller understanding and appreciation of it.<br />

Mishqui-Yacu–<strong>sweet</strong> <strong>water</strong>–thanks to the Cañaris who have breathed<br />

new freshness into it. That is what this book is about.<br />

Pablo Glikman<br />

Country Portfolio Manager<br />

Latin America and the Caribbean Division<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>

[<br />

<strong>mishqui</strong>-<strong>yacu</strong>, <strong>sweet</strong> <strong>water</strong> ]

Ecuador: Reign of Contrasts<br />

14<br />

Within the Latin American context, Ecuador is a small country<br />

with a land area of 284 000 km 2 and approximately 12.5 million<br />

inhabitants. Nevertheless, it is a country characterized by contrast,<br />

a mosaic of unique geographical regions populated by peoples whose<br />

ancestors have either lived there for thousands of years, or arrived<br />

from Europe and Africa over the last five hundred years. 1<br />

Cut in two by the Equator, Ecuador has a climate similar to that of<br />

Equatorial Africa. However, the chilly Humboldt Current, sweeping<br />

along the coast and the Andes, running like a vertebra from north to<br />

south, create a varied landscape that shelters a wide range of distinctive<br />

ecosystems: hot coastal plains with banana, sugarcane and<br />

cocoa plantations, lined by long stretches of unspoilt sandy beaches;<br />

river estuaries harbouring mangrove swamps, although many are<br />

being cut back to make way for shrimp farms (often operated by itinerant<br />

workers from the highlands not far away). A few hours drive<br />

will take you to cool valleys where wet mists often hide the blue<br />

skies. Huge mountain peaks or threatening volcanoes shelter these<br />

places from the steaming jungles that lie on the other side of the<br />

Andean range.<br />

The Ecuadorians divide their nation into roughly three different<br />

areas: the Coast, the Andean Highlands, and the East, i.e. the<br />

Amazonas.<br />

The Highlands<br />

The Ecuadorian Andes are formed by two parallel chains of mountains,<br />

the Cordillera Occidental and the Cordillera Real or Oriental,<br />

both with peaks ranging from 4 000 to 4 500 m above sea level. These<br />

ranges are joined at intervals by transverse foothills, called knots.<br />

Between these two ranges lie the valleys of the Highlands, called<br />

basins, situated from 2 200 to 2 800 m. The basins are quite fertile,<br />

1<br />

There are at least ten different native ethnic groups in Ecuador, each of which considers<br />

itself a distinct nationality with its own language and culture. Furthermore, there<br />

are descendants of Africans and Europeans. A 1993 census divides the population into<br />

roughly the following groups: mestizos 40%, indigenous peoples 40%, whites 10-15%,<br />

blacks and mulattos 5-10% (Holmberg (1998), p.5).

with most characterized by volcanic soils. A river flows from each<br />

basin to the east or west. These highland valleys have been populated<br />

for many centuries. From the valley floors, a patchwork of small<br />

fields extends far up on the mountainsides, demonstrating the intensive<br />

use made of every available inch of land.<br />

The diverse cropping systems that have developed in the<br />

Highlands are based on complicated farming systems, integrating<br />

the cultivation of maize, potatoes (and similar tubers), quinoa, and<br />

leguminous plants. Breeding of domesticated animals such as<br />

camelids (llamas, alpacas and vicuñas) and guinea pigs has developed<br />

in these areas. When the Spaniards arrived in the sixteenth<br />

century, they brought drastic changes, including the introduction of<br />

entirely new species such as wheat, barley, rice, sugar cane, horses,<br />

cows and pigs. New agricultural techniques such as the use of animal<br />

power and ploughs with iron shares revolutionized agriculture,<br />

upset age-old traditions and threatened the sensitive volcanic soil<br />

ecosystems.<br />

During the last century, the coastal areas witnessed spectacular<br />

growth in agricultural production but output was mainly destined<br />

for international markets, while the Andean valleys continued to<br />

produce most of the food for domestic consumption. However,<br />

Ecuadorian agriculture is under threat. The ever-increasing reduction<br />

of plant cover on Andean hillsides has led to an alarming drop<br />

in <strong>water</strong> resources, while illegal use of artificial agricultural inputs<br />

is damaging the environment.<br />

15<br />

ESMERALDAS<br />

CARCHI<br />

IMBABURA<br />

PICHINCHA<br />

SUCUMBIÓS<br />

MANABÍ<br />

COTOPAXI<br />

NAPO<br />

GUAYAS<br />

TUNCURAHUA<br />

LOS<br />

RIOS BOLÍVAR<br />

CHIMBORAZO<br />

PASTAZA<br />

CAÑAR<br />

MORONA<br />

SANTIAGO<br />

AZUAY<br />

EL ORO<br />

[ Ecuador ]<br />

LOJA<br />

ZAMORA<br />

CHINCHIPE

The land’s diminishing production capacity has affected the living<br />

conditions of Andean rural poor families. Their opportunities to earn<br />

a decent income are diminishing, health conditions are deteriorating<br />

and desperate farmers often see migration as the only way to escape<br />

a bleak future of poverty. 2 Ecuadorian rural life is being affected by<br />

two land reforms, ever-increasing social mobility and a changing<br />

political landscape. However, the discouraging fact remains that<br />

three-fourths of the farmers still try to make a living from plots of<br />

less than five hectares, which is seldom enough to meet even the<br />

most minimal needs of their families. 3 Seventy-five per cent of<br />

Ecuador’s rural poor continue to live in a state of absolute poverty. 4<br />

16<br />

Thirst for Water in Hatun Cañar<br />

In the southern part of the Ecuadorian Andes, there is the basin of<br />

the Cañar River – a huge, undulating valley circumscribed by the<br />

knots of Azuay and Buerán and the mountain ranges of Cordillera<br />

Occidental and Cordillera Real. This is the heartland of Hatun<br />

Cañar, the old ‘nation’ of the Cañari people, whose descendants still<br />

live in the area. 5<br />

The swift-running, clear Cañar River cuts through a landscape<br />

that is emerald green and lush during the rainy season (October-<br />

April) and withered brown and grey during the dry months. During<br />

this dry season, rainfall comes well short of meeting the demand for<br />

<strong>water</strong>, while several areas suffer from lack of <strong>water</strong> throughout the<br />

year. Climatological peculiarities and soil quality present remarkable<br />

variations within short distances. Although most of this area is under<br />

irrigation, <strong>water</strong> is limited everywhere and is used infrequently and<br />

insufficiently. Cañari people work hard to build and maintain irrigation<br />

ditches, trying to make the best possible use of every available<br />

source of <strong>water</strong>. However, the existing irrigation infrastructure<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

Gómez (1989) presents a comprehensive summary of Ecuadorian geography.<br />

Rossing (1996), p. 102.<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> (1995), p. 6.<br />

Bolivar Zaruma (1980), pp. 17-20. Ecuador is divided into 22 provinces, subdivided into<br />

cantons. Each canton is administered by a Municipal Council, headed by a mayor. The<br />

province of Cañar is administered by a Provincial Council, situated in the town of<br />

Azogues and is divided into the cantons of Azogues, Biblián, La Troncal, Déleg, Cañar,<br />

El Tambo and Suscal. The three last mentioned cantons roughly constitute the area of<br />

the Upper Basin of the Cañar River (Freire Heredia and Usca (2000), pp. 47 and 59-62).<br />

The area of the Upper Basin covers 99500 ha, with altitudes ranging from 800 to 4 400<br />

m. The census of 1990 estimated its population at 77 100 inhabitants, with the majority<br />

defined as ‘indigenous people’, i.e. Cañaris (<strong>IFAD</strong> (1995), p. 7).<br />

DHV Consultants (1995), pp. 159-60 and 259-60, and <strong>IFAD</strong> (1995), pp. 11-12.

emains rudimentary. There is a constant need for financing and<br />

technical assistance. Disorganized systems hamper <strong>water</strong> distribution,<br />

as well as the sizes, inclination and irregular shapes of the<br />

plots. Every year, inadequate use of irrigation destroys the sensitive<br />

soils, washing them down from hills and mountainsides. Erosion and<br />

lack of protection of <strong>water</strong> sources are caused by indiscriminate<br />

felling of trees and the stripping away of protective plant cover.<br />

Overuse and compression are diminishing soil capacity for <strong>water</strong><br />

absorption. 6 When talking to farmers in the area, <strong>water</strong> is an issue<br />

that never fails to come up. It is common to hear sayings such as:<br />

“Water is to the earth like blood to the humans”.<br />

Still, it is hard to perceive these problems at the end of the rainy<br />

season. Thick mists roll down from the mountainsides or rise from<br />

the distant and invisible seacoast. In several places, <strong>water</strong> gushes<br />

down, while small streams and brooks are seen everywhere. There<br />

are traces of flooding, such as damaged roads and ruined bridges.<br />

You may follow the <strong>water</strong>’s course high up along steep mountainsides,<br />

all the way up to springs and lagoons within the majestic landscapes<br />

of cold and humid plains, sheltered by the awesome peaks of<br />

the mighty Andes.<br />

17<br />

Map of the<br />

CARC project area<br />

Huigra<br />

Capzol<br />

Compud<br />

Llagos<br />

CHIMBORAZO<br />

San Antonio<br />

Gral. Morales<br />

Chontamarca Suscal<br />

Rio Cañar<br />

Gualleturo<br />

Zhud<br />

Juncal<br />

Cañar<br />

Chorocopte<br />

El Tambo<br />

Ingapirca<br />

Honorato Vásquez<br />

CAÑAR<br />

[<br />

Water is to the earth<br />

like blood to the humans ]

The Cañaris<br />

18<br />

A landscape is more than topography, mountains and rivers.<br />

Almost every piece of land in the world is intimately related to the<br />

lives of the people who make a living there. Those who named the<br />

Cañar river – the Cañaris – constitute the most distinguished group<br />

of people inhabiting the river basin. Before the Inca invasion, 7 Cañari<br />

was the greatest culture existing in what is now Ecuador. Few traces<br />

remain of the original Cañari culture. The language has disappeared,<br />

and only a few words and customs remain, together with a wealth of<br />

orally transmitted legends and a few archaeological sites.<br />

The Cañaris were divided into a series of independent lordships,<br />

curacazgos. The names remain – Checa, Sigsig, Molleturo,<br />

Cañaribamba and of course Hatun Cañar, apparently the most<br />

important of them all. Cañari society was highly stratified, a fact<br />

reflected by the great wealth of the furnishings of Cañari noble<br />

tombs. Gold and silver came from richly endowed mines within<br />

their territory. 8<br />

Spanish chroniclers mention with awe the Cañaris<br />

valiant and bellicose nature, honed through<br />

constant skirmishes with their neighbours.<br />

In particular, the Spaniards mention<br />

that the Cañaris did not have slaves.<br />

They were distinguished from other<br />

peoples by their language, their way of<br />

dressing and that both women and<br />

men wore their hair very long. The<br />

chroniclers also stressed that there<br />

were more Cañari women than men. Cieza<br />

de León, who visited the territory in 1547,<br />

found 15 women to every man. Ferocious bloodletting<br />

had befallen the Cañaris after the Inca invasion.<br />

Under the Duma, probably a title given to the curaca of Sigsig, the<br />

Cañaris fought against superior odds before being subdued. The<br />

Inca Topa Yupanqui attempted to smash Cañari opposition by removing<br />

the populations of whole villages to the neighbourhood of Cuzco,<br />

replacing them with loyal mitamakuna. The mitamakuna were<br />

Mythic figure of<br />

the Cañari culture<br />

with human, feline, snake<br />

and eagle features

colonists from the Peruvian heartland who settled in occupied territories.<br />

They maintained their ties with their original homeland,<br />

thus forming a nucleus loyal to the state in the midst of foreign<br />

ethnic groups. The imperial policy speeded up the process of<br />

Cañari acculturation, evidenced by the fact that by the arrival of<br />

the Spaniards the Cañaris already spoke Quichua, the language of<br />

the Inca conquerors. The Inca presence is still visible through the<br />

remains of the mighty Ingañan, the paved Inca highway that cuts<br />

through desolate plains high up in the Andes. Within the Cañar<br />

river basin, the Ingañan passes close by the village of Ingapirca,<br />

which lies beneath a combined fortress and temple. An impressive<br />

structure, built with Inca stone masonry techniques using 'cushionshaped'<br />

boulders, Ingapirca is well preserved and Ecuador's most<br />

prestigious Inca site. It was probably built in connection with earlier<br />

Cañari structures, perhaps the political and cult centre of<br />

Hatun Cañar.<br />

The Cañari people continued to suffer under Spanish rule. The<br />

remaining Cañari leaders opted for an alliance with the new<br />

invaders. On their way to conquer Quito, three thousand Cañari warriors<br />

joined the Spanish forces of Benalcázar. The Spaniards noted<br />

their allies’ exceptional bravery and later stated they would have<br />

been lost without their help and efficient guidance. The Cañaris<br />

fought alongside the Spanish throughout the conquest of Ecuador.<br />

The last big campaign they carried out for the Spaniards was the<br />

quelling of huge rebellions in Lita and Quilca in 1554. Nevertheless,<br />

Cañaris received scant recognition from the Spanish for their help.<br />

Already in 1544, many thousands had been forced to work in the gold<br />

and silver mines of their former territory. In 1578, the Spaniards<br />

ruthlessly suffocated a desperate Cañari rebellion. During that campaign<br />

the Spanish forces were helped by descendants of the same<br />

Incas they formerly had fought against with Cañari support. 9 At present,<br />

an estimated 40 000 Quichua-speaking Cañaris are scattered<br />

throughout the province of Cañar. 10<br />

19<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

It was the Inca Topa Yupanqui that attacked the Cañari lands around 1463. With the<br />

fall of Quito in 1492, he finished the conquest of what is now the Ecuadorian Highlands.<br />

The Spanish conquest began in 1530; by 1549, the Spaniards had subjugated<br />

all ethnic groups of the present Highlands.<br />

Pérez et al. (1998), p. 29.<br />

For a summary of Cañari history, see Moreno Yánez (1996), pp. 96-100.<br />

Perrottet (1994), p. 220.

20<br />

With the recent revival of Cañari pride it is now common to hear<br />

the Cañaris recalling the glory of their ancestors, commonly referred<br />

to as the ‘grandfathers’. The names of Cañari warriors who opposed<br />

both Incas and Spaniards are often evoked in Cañari rhetoric and<br />

political discourse. Cañari pride is also evident from the fact that<br />

many of them elect to wear their traditional clothes and long guangos,<br />

the hair braids sported by both men and women.<br />

On market days, Saturdays in the town of Cañar, a great variety<br />

of traditional Cañari dress can be admired. Several men dress in<br />

kushma, a poncho for festive use, black, often knee-long, wool<br />

pants and white cotton shirts, with embroidery on the sleeves and<br />

collars. The women wear the colourful skirts common throughout<br />

the Andes. However, typical features of feminine Cañari dress are<br />

the embroidered blouses covered by a black, red-lined shoulder<br />

wrap. This woollen shawl is fastened by a silver tupu, an ornamented,<br />

thick dress needle often found in ancient Cañari tombs.<br />

Both men and women wear the typical Cañari hat, made of white<br />

felt, with a narrow brim often turned up at the front. Mentioning<br />

Cañari dress in relation to ethnic pride and self-expression is<br />

important, because it is often dress and not 'race' that determines<br />

an indigenous sense of belonging.<br />

The women of Cañar<br />

fasten their woollen shawls<br />

with a silver tupu

[<br />

Dress is an element of ethnic pride for the Cañari people ]

22<br />

My village was quite isolated and we did not see many white people.<br />

Everyone talked to one another in Quichua. It was only during<br />

market days, on Saturdays, when we walked in to Suscal,<br />

that you saw other people. It is still like that in many places. You<br />

work in the fields, or in your home, bringing down the produce<br />

of your land on market days. However, I went to school in Suscal<br />

and it was then I realized that there were different classes of people.<br />

We had to turn ourselves into mestizos in school and that<br />

meant we had to cut off the braid. Many Cañari boys and girls<br />

underwent a painful change in school. We were not allowed to<br />

speak Quichua and several of us were ashamed of our own traditions.<br />

I remember how I completely denied my parents for<br />

three days after cutting my braid and beginning school. When I<br />

was a young man studying to be a teacher, I also entered a profound<br />

identity crisis. Denying my roots completely, I did not<br />

want to be a runa. 11<br />

In 1971, I was the first indigenous person to attend the secondary<br />

school in Cañar. It was very hard for me. I felt apart and discriminated<br />

against. After the third course I left school. It was not<br />

voluntary. A female teacher told me I had to leave because I did<br />

not have a uniform. My parents could not afford to give me one.<br />

She knew that, but I had to leave anyway. I see her sometimes in<br />

the street. She knows I remember her. 12<br />

An area where the Cañari traditions are particular powerful is traditional<br />

medicine. The Upper Basin of the Cañar River Rural<br />

Development Project (CARC), discussed in this book, includes a small<br />

component aimed at instructing beneficiaries in the usefulness of several<br />

herbs and plants. This activity has proved to be useful in introducing<br />

people to the importance of preventive health care.<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

Interview with José Lema. Runa, the Quichua word for man, is often used in a derogatory<br />

way.<br />

Interview with Rebeca Pichazaea.<br />

Interview with Paola Guaman. The Rebeca mentioned in this quotation is Rebeca<br />

Pichazaea.

Medicines offered by the pharmacies are too expensive for us. One<br />

of my girls was very sick. One day I had to pay 60 000 sucres for<br />

medicine. Another day, 200 000 sucres. The doctor told me to buy<br />

the medicine; I did not know what it was. I know that pharmacy<br />

medicine is often necessary. However, if we cannot afford such<br />

medicine we have to use the knowledge our grandmothers passed<br />

down to us. They had knowledge and experience of their own.<br />

When things get really bad we have to go to the doctor, the pharmacy,<br />

the hospital. Rebeca helps us with her knowledge of western<br />

medicine. Nevertheless, she is also very knowledgeable about<br />

our own traditions. She has been taught in health centres. She<br />

knows about bleeding and childbirth. Our group of women meets<br />

with her and she tells us how to recognize the plants, how to grow<br />

them and where to sell them. I make some money out of it. I have<br />

had my gift, my knowledge, for many years. On Tuesdays and<br />

Fridays, people come to me to be cured. I know about bad air,<br />

fright, cold and many other visitations. I know how to cure them<br />

with herbs, baths, cleansing and massage. 13<br />

Acknowledgement of Cañari traditional medicinal knowledge is an<br />

important part of the agenda of several indigenous organizations.<br />

Cañari healers are called yachakes and may be men or women. There<br />

is an informal hierarchy of yachakes, who interact with one another.<br />

Some of them have apprentices. A common feature is that all<br />

yachakes consider themselves in the service of Pacha Kamak (God).<br />

In order to be effective in their cures they have to be bestowed with<br />

Pacha Kamak’s grace, i.e., have a calling.<br />

23<br />

José Lema<br />

interviews a Cañar<br />

farmer who wears<br />

the guango (braid)<br />

Knowledge of herbs<br />

and plants for medical<br />

purposes is part of the<br />

Cañari tradition

24<br />

Much of the traditional medicine centres on concepts concerning<br />

loss and gain of energy. Curative powers are invoked from Pacha<br />

Mama (Mother Earth) in the form of herbs and from Mama Killa<br />

(Mother Moon) and Taita Inte (Father Sun) in the form of healing<br />

rays. Healing is practised through massages, immersion in herbal<br />

baths, showering, 14 passing guinea pigs over afflicted areas, exposure<br />

to sun or moon, and the drinking of various herbal decoctions.<br />

Healing sessions are often carried out in the house of the yachak,<br />

but also in the few, prestigious houses of healing, jambi wasi.<br />

The headquarters of the Unión Provincial de Comunas y<br />

Cooperativas del Cañar (UPCCC), the most influential indigenous<br />

organization in Cañar, called Nucanchic Huasi, houses a recently<br />

constructed jambi wasi. A woman healer, Mercedes Chuma, attends<br />

patients on a daily basis. Besides serving as a centre for traditional<br />

medicine, UPCCC’s jambi wasi also functions as a place where serious<br />

diseases can be identified and patients passed on to modern<br />

health care. 15<br />

Any development project intent on interacting with Cañari culture<br />

should be inscribed within the Cañari landscape. To a large extent,<br />

the surrounding landscape conditions thinking and acting within<br />

traditional Cañari culture.<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

17<br />

18<br />

The yachak sprinkles agua ardiente (strong alcohol made from sugarcane), through<br />

his/her lips over the patient.<br />

Interview with Mercedes Chuma.<br />

Mummies were not buried in the ground, but placed in natural cavities. The cult of the<br />

dead had an enormous importance in Andean societies. Corpses, mallquí in Quichua,<br />

were considered to be intermediaries between huacas and the living. Huaca is anything<br />

endowed with spirtual force, like gods and spirits, but also mountains, lagoons and<br />

other powerful places and phenomena. As they were connected with huacas, it was<br />

natural to place the mallquís within the spiritual realm of the mountains (Bernand<br />

(1996), pp. 74-79).<br />

Landivar (1997), pp. 34-54.<br />

A Cañari author, Luis Bolivar Zaruma, seeks the roots for the Cañari tendency to individualize<br />

nature and natural phenomena in Quichua, the language spoken by Cañaris.<br />

“In this language, and others spoken on the American continent, the content, the meaning<br />

and what is indicated can only be described by using things in the real world.<br />

Occidental theology and philosophy were not assimilated by Cañaris because Quichua<br />

is a concrete language consisting of concrete symbols describing the world and<br />

things; there does not exist a capacity for abstraction” (Bolivar Zaruma (1980), p. 25).

Mountains: Realm of Power<br />

Andean peoples have always looked to the mountains with awe and<br />

veneration. Mummies wrapped in precious clothing may still be<br />

found among Andean peaks, remains of human sacrifices to the<br />

Mountain-Lords. 16 Legends are constantly spun of the mountains.<br />

They are said to be inhabited by imaginary creatures, half beasts,<br />

half humans, vengeful and threatening, constantly thirsting for<br />

human blood. The list of such monsters is long and intimidating:<br />

gagones (demon dogs), carbuclos (demon cats), shiros (malevolent<br />

dwarfs hunting for women), cuscungus (birds of prey announcing<br />

death), chuzalongos (blood sucking children), agcha shuas (werewolves),<br />

mama huacas (female man chasers) and many more. 17<br />

Mountains are often described as individuals, ancient, mighty and<br />

difficult to comprehend. 18 Like benevolent parents, they watch over<br />

the tiny hamlets and towns that huddle in their shadows. Mountains<br />

send <strong>water</strong> to the people, and conceal treasures in their depths. If<br />

sometimes they are benevolent, at other times they are capricious<br />

and dangerous, hurling disasters over defenceless humans in the<br />

form of hurricanes, landslides, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes.<br />

“Urcu signifies mountain, chuncana play and cui comes from take<br />

care of or deliver. Thus, urcu chuncanacui signifies a game of give<br />

and take between the mountains. During nights well lit by the moon,<br />

when yellow lightning appears among the mountain peaks, it is<br />

believed that the mountains are exchanging treasures and animals<br />

between themselves. The mountain Taita Bueran is believed to have<br />

six children, but he is separated from them by his spouse, the mountain<br />

Hacron Ventanas; it appears as if those two quarrel quite a lot.<br />

25<br />

Mountains have <strong>water</strong><br />

and conceal treasures<br />

in their depths

It is thus that the mountains in general are deeply respected and<br />

much is expected from them. For example, many people are afraid to<br />

approach the mountain Culebrillas with dried or cold meat, because<br />

they say this may raise the Hurricane from the páramo, high moor,<br />

thus not allowing entrance to anyone”. 19<br />

High moors are wide plains situated from 3 000 to 4 200 m and covered<br />

with a yellowish grass used to feed cattle and sheep. In the<br />

Cañar area, many high moors are common lands, owned and used by<br />

members of communities further down in the valleys.<br />

Culebrillas: Where the Water Is Born<br />

26<br />

The high moor surrounding the mysterious lagoon of Culebrillas is<br />

jointly owned and used by four communities within the El Tambo<br />

canton. This tranquil lake is situated at 3 880 m, in the shadow of the<br />

impressive Yanaurcu, the Black Mountain. 20 It appears to be a barren<br />

land, but several traces of ancient civilizations are located there.<br />

The Ingañan passes close to the lake. This highway was originally<br />

paved and maintained all the way from Cuzco to Quito. Among the<br />

remains of this road, several stones indicate the site of a tambo, a<br />

kind of inn or resting-place for the travellers who passed along the<br />

Ingañan.<br />

South of the lagoon is a flat area with a quarry, called<br />

Labrazhcarrumi by the locals. Labrazhcarrumi consists of some huge<br />

rectangular boulders spread over an area of about 100 km 2 . The purpose<br />

of these stone blocks is unknown. However, people used to<br />

19<br />

20<br />

21<br />

Castro Muyancela (1995), pp. 314-15. Manuel Castro Muyancela is the newly elected<br />

mayor of Suscal and an influential indigenous politician at the national level. “The<br />

Hurricane” is the personification of the violent storms that brew high up in the mountains.<br />

Pinos & Rodríguez (1994), p. 1, and Heriberto Rojas (1991), pp. 19-20.<br />

The legend is retold with the help of stories told by Rebeca Pichazaea and Francisco<br />

Chimboroza.

elieve that the Incas cut them in order to dam the lagoon. Even if<br />

people lived and worked here 500 years ago, it is now a very desolate<br />

place. A spectacular landscape, inhospitable and mysterious, and<br />

chilled by mountain mists, it is the natural centre of a web of legends,<br />

known in innumerable versions by almost any Cañari.<br />

“A soldier married a fair maiden. However, unknown to him, she<br />

had been up in Cullebrillas. An enormous serpent living in the lake<br />

had seen her there. The terrible creature had fallen in love with the<br />

maiden and wanted to keep her to himself. On the wedding day, the<br />

serpent broke into the house where the celebrations took place,<br />

snatched the bride and brought her up to his lair at the bottom of the<br />

lagoon. The infuriated groom armed himself with a spear and an axe<br />

and followed in the tracks of the snake. He found his bride by the<br />

shore of the lagoon. The huge serpent had his coils around her, while<br />

he rested his head on her lap. The bride made a sign to her spouse.<br />

Obeying her, he hid behind a stone while she sang a lullaby to the serpent.<br />

When the animal had fallen asleep, the spouse came forth and<br />

plunged his spear into it. The frenzied serpent wriggled and spat<br />

venom, but the valiant soldier cut off its head. In death agony, the serpent<br />

left the lakeside. It slithered away to the south, opening up the<br />

earth with its heavy body. Thus the serpent created the course and<br />

meanders of the stream Culebrillas, the stream that feeds the <strong>water</strong><br />

of the lagoon into the river of San Antonio. Since that day, the <strong>water</strong><br />

of the mountains reaches the entire region of El Tambo. The lady<br />

eventually gave birth to a white child, the son of the serpent. Since<br />

this boy did not belong anywhere, he caused a lot of trouble”. 21<br />

27<br />

Lagoon of<br />

Culebrillas<br />

People used to believe that<br />

rectangular boulders were cut<br />

by the Incas to dam the lagoon

28<br />

This legend reflects several popular ideas about the high moor, an<br />

abode of sacha (the unknown, the savage) as opposed to uca (the<br />

familiar, the tangible). The high moor constitutes a twilight zone<br />

between the wild and the domesticated. The <strong>water</strong> is born there, but<br />

also storms and diseases. The high moor is the realm of children and<br />

women. They are the ones who tend the sheep and collect the grass<br />

found there. Children are also related to the high moor in a symbolic<br />

way. Adolescents in particular find themselves in a threshold<br />

between the world of adults and infants. Accordingly, they have<br />

something in common with the high moor, placed as it is between the<br />

inhospitable mountain peaks and the tended fields. Women are also<br />

symbolically connected with the high moor, since they are considered<br />

more of a part of nature than men are. This is probably due to<br />

their role as lifebringers and nurturers, something that connects<br />

them with Pacha Mama (Mother Earth). 22<br />

The serpent the woman of the legend met in Culebrillas is probably<br />

related to the most feared phenomenon in Cañari mythology, the<br />

serpent of the sky – Taita Cuichi (Father Rainbow), harbinger of<br />

both life and destruction. Taita Cuichi lives by lakes. He always has<br />

one foot in the <strong>water</strong>. When threatened he disappears into the lake,<br />

leaving a column of smoke behind him. The one who breathes in that<br />

smoke will suffer from cuichi japischca (capture of the rainbow), a<br />

deadly disease that must be treated immediately through herbal<br />

potions and curative baths. 23<br />

[<br />

The real wealth of the<br />

lagoon is the <strong>water</strong> ]

There are several kinds of rainbows and they cause various diseases.<br />

The worst affliction is when Taita Cuichi takes a woman, i.e.<br />

makes her pregnant. The affected woman then suffers intense<br />

headaches, pains in the legs and arms, nausea and stomach-ache.<br />

The woman contaminated by the seed of Taita Cuichi has to eat bitter<br />

herbs in order to vomit the uninvited intrusion. Fear of Taita<br />

Cuichi is very strong in certain areas of Cañar. He is often called the<br />

Devil dressed in colours. It has been speculated that the strange perceptions<br />

regarding Taita Cuichi are the result of a mixture of old pre-<br />

Columbian myth and more recent facts and life experiences. For<br />

example, the child of Taita Cuichi is always white and this may indicate<br />

the unwanted result of a forced relationship with the former<br />

masters of the area, Spanish intruders and/or the owners of the<br />

land. 24 However, the serpent of Culebrillas is not only a sinister creature;<br />

he is also the guardian of treasures:<br />

They say there is a treasure resting at the bottom of the lagoon.<br />

Heavy beams of pure gold were sunk there by our ancestors, probably<br />

as sacrifices to their gods. A few years ago our communities<br />

kept a guard up there [at Culebrillas]. He was well paid, but one<br />

day he disappeared and was never seen again. People assume he<br />

found the treasure, or part of it, and simply ran away with it. He<br />

probably left for the United States or Europe. 25<br />

Even if there is a lot of talk about the hidden treasures of the lagoon,<br />

people are well aware that the real wealth of the place is not gold or<br />

silver, but <strong>water</strong>. Taita Cuichi’s main function is to protect <strong>water</strong> and<br />

fertility and bestow it on humans. However, every farmer in Cañar<br />

knows that the thorny issue of access to <strong>water</strong> has to be handled with<br />

care and tact. Anyone who interferes with a <strong>water</strong> source like<br />

Culebrillas is destined to get into trouble. Taita Cuichi’s legendary<br />

presence can be seen as a warning. Be careful when you deal with<br />

the <strong>water</strong>s of Cañar. You do not know what hidden powers and buried<br />

conflicts you may uncover.<br />

29<br />

22<br />

23<br />

24<br />

25<br />

Bernal et al. (1999), pp. 49-51.<br />

Landívar (1997), pp. 37-39 and Einzmann and Almeida (1991), pp. 92-93.<br />

Einzmann and Almeida (1991), pp. 93.<br />

Interview with Manuel Zaruma, of Molino Huayco, who accompanied us to Culebrillas.

Culebrillas is one of the main <strong>water</strong> sources of the Cañari basin. It<br />

is the birth place of the San Antonio River, which eventually joins<br />

with the Cañar River after delivering <strong>water</strong> to no less than 14 irrigation<br />

canals, providing <strong>water</strong> to 2 639 hectares in the cantons of El<br />

Tambo and Juncal, thereby benefiting 1 100 families. 26 The lagoon of<br />

Culebrillas feeds other <strong>water</strong> systems as well, and the construction<br />

of an efficient dam by the lake would benefit even more people,<br />

bringing a constant flow of <strong>water</strong> to huge areas of dry land.<br />

Water and Development<br />

30<br />

Agriculture occupies a prominent position in all debates concerning<br />

development policies. Food production is not a simple question of profitability;<br />

it is a burning social issue. Although a country may profit from<br />

producing agricultural goods for international markets, this does not necessarily<br />

solve problems related to providing food for a starving population.<br />

An efficient agricultural sector that benefits both small and big producers<br />

may facilitate a more just and equal distribution of a nation’s wealth. It<br />

may stem the migratory flow from rural areas and probably raise living<br />

standards, efficiency, freedom of choice and the well-being of a large rural<br />

population.<br />

Compared with many other countries, Ecuador is endowed with a good<br />

share of natural resources, not only precious metals and oil, but also a conducive<br />

environment for efficient agricultural production. The country has<br />

benefited from the growth of export markets for products such as bananas,<br />

cocoa, shrimp and other items. This production from the coastal plains has<br />

received support from the nation’s decision-makers. The development and<br />

growth of other coastal products, like rice, maize and soybeans, also benefit<br />

from various kinds of state support. In mountain areas, milk production<br />

has been modernized completely while state support has enabled both<br />

local and imported technologies to be purchased.

Nevertheless, most small producers in the Highlands have not been able<br />

to benefit from any investments aimed at increasing production. Food production<br />

for national consumption cannot meet demand; in several rural<br />

areas, there has even been a drop in production. In the Cañar area, products<br />

such as wheat, which once was a main crop, have lost importance primarily<br />

due to state-subsidized imports.<br />

International development agencies, as well as some government institutions<br />

and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), have tried to counter<br />

this deteriorating situation. Numerous experiments and investigations<br />

have been carried out. Annual reports seem to concur that efficient irrigation<br />

is the most critical concern of Andean farmers. 27<br />

Irrigation systems have existed in Ecuador since pre-Columbian times.<br />

However, until 1944, irrigation was developed exclusively through private<br />

initiatives. In that year, a National Office for Irrigation (ONR) was founded.<br />

In 1966, ONR was replaced by the Ecuadorian Institute for Hydraulic<br />

Resources (INERHI), which plans and builds irrigation projects in addition<br />

to monitoring and overseeing the use of <strong>water</strong> resources. 28<br />

Any person familiar with <strong>water</strong> management at the grass-roots level<br />

knows that huge investments in irrigation inevitably face a wide range of<br />

problems. INERHI-executed projects have often encountered serious problems,<br />

mainly owing to a lack of cooperation from farmer communities.<br />

Conflicts have frequently arisen among beneficiaries. Lack of organization<br />

among irrigation users has inhibited efficient <strong>water</strong> management. Bad<br />

maintenance has destroyed valuable infrastructure. The so-called tertiary<br />

systems, small canals reaching the farmers’ plots, have often not been built,<br />

since such work requires efficient organization among beneficiaries. 29<br />

Water management calls for discipline, solidarity and social skills.<br />

Cement and good engineering are not enough to create functional irrigation<br />

systems. Cooperation among all the parties involved is essential.<br />

Openness and social skills are probably the most decisive factors in makeing<br />

irrigation systems effective.<br />

31<br />

26<br />

27<br />

28<br />

29<br />

DHV Consultants (1995), p. 165.<br />

de Janvry and Glikman (1991), pp. 224-27. Thirty-one per cent of the cultivable land is<br />

irrigated. Thirty per cent of this <strong>water</strong> is used by more than 70% of the agriculturists,<br />

while 70% is used by big plantations (Cisneros et al. (1999), p. 5).<br />

de Janvry and Glikman (1991), p. 228.<br />

Ibid., p. 270. In 1994, INERHI was replaced by the National Council for Hydraulic<br />

Resources (CNRH) (Cisneros et al.) (1999), p. 5. The Ecuadorian State has initiated a<br />

process of institutional transformation, delegating several formerly state-controlled<br />

activities to municipalities, NGOs, civil society and the private sector. INERHI (CNRH)<br />

has on several occasions been mentioned as one of the organizations that ought to be<br />

removed from state control (<strong>IFAD</strong> (1995), p. 20).

[<br />

There was a lack of communication between planners and future beneficiaries ]

Cañari Development Initiatives<br />

The Cañari people are not without a voice. Decades of political<br />

struggle have given rise to several organizations that are firmly rooted<br />

within their communities. On the agenda of all these organizations<br />

is the search for institutions and agencies willing to provide<br />

financing and assistance to rural development projects. During the<br />

1980s, plans to support agricultural projects were developed<br />

between grass-roots organizations and a regional development<br />

agency, the Centre for Economic Re-Conversion of Azuay, Cañar and<br />

Morona Santiago (CREA).<br />

In 1980, just after the reintroduction of a democratic government,<br />

30 rural development issues were again addressed and the<br />

Ecuadorian State declared it was prepared to: “...apply an integrated<br />

concept while attending to problems related to the peasantry, proposing<br />

dynamic participation from peasants in order to transcend<br />

simple, technical, production-oriented solutions”. 31<br />

CREA was established in 1958 in response to a crisis that hit the<br />

production of exclusive, so-called Panama straw hats, which was<br />

concentrated in the province of Cañar. 32 A sudden drop in demand<br />

affected 100 000 people engaged in this artisan activity. CREA’s main<br />

function is to participate in the planning of regional development<br />

projects in the provinces of Cañar, Azuay and Morona Santiago. It<br />

coordinates the development initiatives of national and international<br />

agencies operating in the area. CREA also executes rural projects<br />

in its own right or in direct association with other entities (both private<br />

and public). 33<br />

33<br />

30<br />

31<br />

32<br />

33<br />

From 1963 to 1965, Ecuador was governed by the military, and from 1966 to 1968, the<br />

country had an acting president, who had not been elected through general elections.<br />

In 1968, José Maria Velasco Ibarra was elected president for the fifth time. In 1972, he<br />

was ousted from power by the military, which ruled the country until 1979.<br />

Government resolution quoted in de Janvry and Glikman (1991), p. 209.<br />

These hats originated in Ecuador, but got their name because they became popular<br />

among the builders of the Panama Canal. From 1898, US troops fighting in tropical<br />

wars were equipped with Ecuadorian Panama-hats (50 000 hats were issued to soldiers<br />

who fought in the Caribbean and The Philippines). The industry peaked in 1946<br />

when 5 million hats were exported, constituting 20% of Ecuador’s annual export earnings.<br />

Then the fashion gradually changed, leading to severe crisis by the end of the<br />

1950s (Perrottet (1994), pp. 131-33).<br />

de Janvry and Glikman (1991), pp. 283-85.

34<br />

In 1982, CREA approached the Ecuadorian government with a proposal<br />

for future cooperation with <strong>IFAD</strong> within the Cañar area. 34 In<br />

1987, an <strong>IFAD</strong> mission identified the province of Cañar as a priority<br />

area for implementing a possible rural development programme with<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> funding. The process of elaboration was concluded in 1990 by<br />

an <strong>IFAD</strong> appraisal mission, which presented a report that formed the<br />

basis for a loan agreement signed by <strong>IFAD</strong> and the Ecuadorian<br />

Government. In 1992, the Government of The Netherlands agreed to<br />

cofinance the project. Despite this long and complicated process,<br />

the CARC project ran into serious problems even before it got started.<br />

The project was supposed to address a wide range of issues related<br />

to agricultural production.<br />

“The principal objective of the project is a significant improvement<br />

of the real wages of the small agriculturists of the upper basin<br />

of the Cañar River through the introduction of irrigation and adequate<br />

technology for a productive development of their farms”. 35<br />

Accordingly, several components were integrated from the start:<br />

credit, technical assistance, infrastructure, organization of agriculturists<br />

and productive activities of women. However, it was repeatedly<br />

stressed that the core of the programme would be irrigation.<br />

“This component [the construction and rehabilitation of irrigation<br />

systems] is the fundamental activity above which all other elements<br />

of the project are constructed. In fact, it is only after incorporating<br />

irrigation in adequate measures with a significant geographical reach<br />

that it will be possible to introduce new technologies and necessary<br />

practices to raise agricultural production for the beneficiaries”. 36<br />

The thorny issue of irrigation eventually caused feelings to run<br />

high within the proposed project area. The storm centre was<br />

Culebrillas, mystical abode of Taita Cuichi, birthplace of most of the<br />

Cañari <strong>water</strong>s.<br />

34<br />

35<br />

36<br />

37<br />

38<br />

39<br />

Pinos and Rodríguez (1994), p. 21.<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> (1990), p. 63.<br />

Ibid., p. 69.<br />

Quoted in Villarroel, G. (1992).<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> (1990), pp. 69-70.<br />

Villarroel, G. (1992). A parish is the administrative unit below a province. Suscal is now<br />

a province. Before El Tambo and Suscal were cantonized, the province of Cañar included<br />

14 parishes. Now, 12 parishes operate under Cañar, while the provinces of El Tambo<br />

and Suscal are situated like islands within the much bigger province of Cañar. The<br />

province mayors are elected in general elections, while the political deputies that govern<br />

the parishes are appointed by the Government.

The Initial Proposal<br />

In 1992, it was stated that “one of the most important works<br />

around which the development project for Cañari peasants revolves<br />

is the construction of Culebrillas dam”. 37 The <strong>IFAD</strong> appraisal mission<br />

in 1990 described the damming up of Culebrillas in the following<br />

way:<br />

“The sub-system of Culebrillas implies the construction of a 14 m<br />

high and 72 m long earthen dike that will create a dam above the<br />

mentioned lagoon and endow its outlet (San Antonio River) with a<br />

capacity of 10.5 cubic hectometres. These regulatory works will, on<br />

the one hand, permit a maximal flow of 680 litres/second to the subsystem<br />

of El Tambo, which furthermore will be significantly amplified<br />

(991 additional ha) through the prolongation with 4 km of the<br />

principal canal (Canal Coronel); on the other hand, additional <strong>water</strong><br />

will be directed towards a new principal canal...permitting the irrigation<br />

of around 777 ha within the areas of Juncal, Suscal and<br />

Chontamarca”. 38<br />

Two years later, it was thought that: “It [Culebrillas system]<br />

will…permit the storage of 7 million cubic metres of winter <strong>water</strong><br />

that could be used during summer to irrigate 2 700 ha of land<br />

through a network of improved canals and the construction of a new<br />

one towards the parish of Suscal”. 39<br />

Preliminary studies of this dam and its connected networks of<br />

canals were made by CREA, the Inter-American Institute for<br />

Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), INERHI and Latinoconsult, an<br />

Argentine consultancy firm. CREA would be responsible for the irrigation<br />

component of the CARC project, while INERHI would provide<br />

technical assistance and be in charge of all construction works related<br />

to irrigation.<br />

35<br />

[<br />

The thorny issue<br />

of irrigation ]

36<br />

It was an ambitious project. However, it was too much of a blueprint<br />

solution. The project was based on concrete. All thinking<br />

was concerned with cement. They planned building the dam and<br />

the canals, forgetting the fact that irrigation is not only a question<br />

of providing more <strong>water</strong>. It is essentially a question of providing<br />

good management. You have to organize the use of the <strong>water</strong><br />

upstream and all the way down. An issue involving human relations.<br />

The <strong>water</strong> associations did already exist, but they were not<br />

involved in the planning process. Therefore, the conflict did not<br />

come as a surprise. 40<br />

Four different irrigation systems were planned. However, it was the<br />

plans for Culebrillas that raised fierce opposition, probably because<br />

14 existing canals were going to be affected. A new canal meant that<br />

all 14 canals were going to be reorganized. Current canal users felt<br />

excluded from the entire planning process. They feared that traditional<br />

access to older irrigation systems was severely threatened,<br />

and were convinced they would lose <strong>water</strong> through project innovations.<br />

The situation was worsened by plans to distribute <strong>water</strong> from<br />

Culebrillas to the area of Suscal. Even though the proposed dam in<br />

Culebrillas had more than enough capacity to feed both irrigation<br />

systems, users of the existing canals calculated that the new systems<br />

would make everything worse. Since the new systems would be much<br />

bigger than the older ones, the original users of the Culebrilla <strong>water</strong><br />

assumed that meant less <strong>water</strong> for everyone. Didn't the introduction<br />

of a new canal to Suscal run the risk that El Tambo would lose much<br />

of its <strong>water</strong>?<br />

The project CARC had decided to make the dam. Nothing else; it<br />

was news to us. Suddenly the fact was there. A certain engineer<br />

Carran explained that the <strong>water</strong> was going to Suscal. All <strong>water</strong><br />

was going to be assembled in one canal, the Canal Coronel. We<br />

thought that meant no <strong>water</strong> to El Tambo. There was talk of rebellion,<br />

of suing CARC and all agencies involved. 41<br />

40<br />

41<br />

42<br />

43<br />

44<br />

Interview with Rudolf Mulder, Dutch Co-Director to CARC.<br />

Interview with Julián Guaman, president of the <strong>water</strong> committee of the Canal Cachi-<br />

Banco Romerino Pillocapata.<br />

León (1993), pp. 1-3.<br />

Interview with Daniel Rodríguez, former mayor of El Tambo.<br />