A BROADER VIEWOF HEALTH: - UCLA School of Public Health

A BROADER VIEWOF HEALTH: - UCLA School of Public Health

A BROADER VIEWOF HEALTH: - UCLA School of Public Health

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

U C L A<br />

PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

NOVEMBER 2010<br />

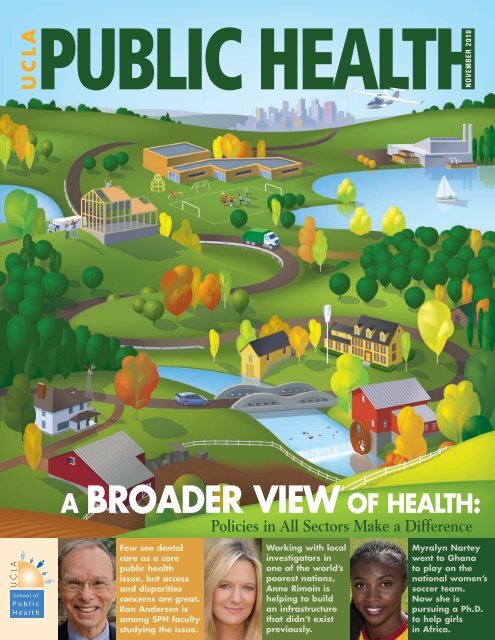

A <strong>BROADER</strong> VIEW OF <strong>HEALTH</strong>:<br />

Policies in All Sectors Make a Difference<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong><br />

Few see dental<br />

care as a core<br />

public health<br />

issue, but access<br />

and disparities<br />

concerns are great.<br />

Ron Andersen is<br />

among SPH faculty<br />

studying the issue.<br />

Working with local<br />

investigators in<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the world’s<br />

poorest nations,<br />

Anne Rimoin is<br />

helping to build<br />

an infrastructure<br />

that didn’t exist<br />

previously.<br />

Myralyn Nartey<br />

went to Ghana<br />

to play on the<br />

national women’s<br />

soccer team.<br />

Now she is<br />

pursuing a Ph.D.<br />

to help girls<br />

in Africa.

PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

<strong>UCLA</strong><br />

U C L A<br />

Gene Block, Ph.D.<br />

Chancellor<br />

Linda Rosenstock, M.D., M.P.H.<br />

Dean,<strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong><strong>of</strong><strong>Public</strong><strong>Health</strong><br />

Sarah Anderson<br />

AssistantDeanforCommunications<br />

John Sonego<br />

AssistantDeanforDevelopment<br />

andAlumniRelations<br />

Dan Gordon<br />

EditorandWriter<br />

Martha Widmann<br />

ArtDirector<br />

E D I TO R I A L B OA R D<br />

Richard Ambrose, Ph.D.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor,Environmental<strong>Health</strong>Sciences<br />

Roshan Bastani, Ph.D.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor,<strong>Health</strong>Services<br />

AssociateDeanforResearch<br />

Thomas R. Belin, Ph.D.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor,Biostatistics<br />

Pamina Gorbach, Dr.P.H.<br />

AssociatePr<strong>of</strong>essor,Epidemiology<br />

F. A. Hagigi, Dr.P.H., M.B.A.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor,<strong>Health</strong>Services<br />

Moira Inkelas, Ph.D.<br />

AssistantPr<strong>of</strong>essor,<strong>Health</strong>Services<br />

Richard Jackson, M.D., M.P.H.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essorandChair,<br />

Environmental<strong>Health</strong>Sciences<br />

Michael Prelip, D.P.A.<br />

AssociatePr<strong>of</strong>essor,<br />

Community<strong>Health</strong>Sciences<br />

Andrew Tsui and Tarah Griep<br />

Co-Presidents,<strong>Public</strong><strong>Health</strong>StudentAssociation<br />

Christopher Mardesich, J.D., M.P.H. ’98<br />

President,AlumniAssociation<br />

features<br />

4<br />

WISDOM ON TEETH:<br />

A Growing Focus on<br />

Dental Care Needs<br />

Poor oral health has been called a “silent<br />

epidemic,” with disparities and access problems<br />

calling for more attention from public health.<br />

8<br />

ANNE RIMOIN:<br />

Bringing<br />

Emerging<br />

Diseases Above<br />

the Radar<br />

She is working with the<br />

Congolese to build a disease<br />

surveillance system that<br />

has already revealed the<br />

surprisingly dramatic growth<br />

<strong>of</strong> human monkeypox.<br />

1<br />

<strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong>

A <strong>BROADER</strong><br />

VIEW OF<br />

<strong>HEALTH</strong>:<br />

Policies in<br />

All Sectors Make<br />

a Difference<br />

HIGHER<br />

EDUCATION:<br />

New Strategies for<br />

Promoting <strong>Health</strong><br />

in every issue<br />

0<br />

As momentum builds for considering the<br />

public health effects <strong>of</strong> decisions outside<br />

health’s traditional purview, SPH faculty<br />

are leading the way.<br />

16<br />

With the one-size-fits-all approach a distant<br />

memory, efforts to change health behaviors are<br />

relying on better-targeted messages delivered in<br />

proactive and innovative ways.<br />

23<br />

28<br />

30<br />

32<br />

RESEARCH<br />

Monkeypox rising in<br />

Africa…children not getting<br />

dental care…insurance<br />

inequities for same-sex<br />

couples…dangerous<br />

nanoparticles…home<br />

kitchens not making<br />

grade…centralized health<br />

care fares well.<br />

STUDENTS<br />

FACULTY<br />

NEWS BRIEFS<br />

ON THE COVER<br />

A broader view <strong>of</strong> health takes into account that policies in a wide variety <strong>of</strong> sectors can directly<br />

or indirectly influence the health <strong>of</strong> populations. Matt LeBarre © 2010<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Reed Hutchinson / Cover: Nartey; pp. 28-29<br />

Sandra Shagat, <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> Dentistry / TOC: dentistry; p. 6<br />

Todd Cheney, AS<strong>UCLA</strong> / p. 7: Westwood Predoctoral Dental Clinic<br />

J. Rose Photography by Jessica Williams / p. 7: toothbrush learning station<br />

Matt LeBarre / Cover: Broader View; TOC: Broader View; pp. 11-12, 14-15<br />

Shoshee Jau, Daily Bruin / p. 32<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Anne Rimoin / Cover: Rimoin; TOC: Faculty Pr<strong>of</strong>ile; pp. 8, 23<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Beatriz Solis / p.16: Solis<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Philip Massey / pp. 16-17<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> David Gere / TOC: Higher Education; pp. 18-19<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Antronette Yancey / p. 20<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Roshan Bastani / p. 21<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> / Cover: Andersen; TOC: Dentistry; p. 2; p. 4: Andersen; pp. 5-6;<br />

p. 7: dentist cleaning teeth; p. 10: Fielding; p. 11: Guerrero;<br />

p. 12: Jackson; p. 19: Yancey; pp. 31, 33; back cover<br />

iStockphoto © 2010 / Cover; p. 4: teeth; p. 22; pp. 25-26<br />

<strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Home Page: www.ph.ucla.edu<br />

E-mail for Application Requests: info@ph.ucla.edu<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Magazine is published by the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> for the alumni, faculty,<br />

students, staff and friends <strong>of</strong> the school. Copyright 2010 by The Regents <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> California.<br />

Permission to reprint any portion must be obtained from the editor. Contact Editor, <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong><br />

Magazine, Box 951772, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772. Phone: (310) 825-6381.

2<br />

dean’s message<br />

PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong> HAS LONG ESPOUSED the role <strong>of</strong> many factors<br />

– such as education, housing, employment and the environment – contributing<br />

to overall health status. There is a growing movement to take this broader view<br />

<strong>of</strong> health into all aspects <strong>of</strong> society. As a result, with leadership from several<br />

faculty members at our school, there is a push for policy and decision-makers<br />

to utilize the <strong>Health</strong> Impact Assessment (HIA) when making decisions in<br />

any sector.<br />

Our cover story takes a look at this innovative approach and how, in<br />

addition to our faculty, our students and alumni are working to encourage the<br />

use <strong>of</strong> HIA to evaluate objectively the potential health effects <strong>of</strong> a project<br />

(e.g., a light rail system) or policy (e.g., curbing diesel emissions) before it is<br />

built or implemented. They are applying one <strong>of</strong> the tenets <strong>of</strong> public health –<br />

prevention – not just to individual and community health, but to the policymaking<br />

process.<br />

We are also taking a broader view when it comes to global health. In<br />

addition to activities at the school, faculty and students in a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>UCLA</strong><br />

schools and colleges are participating in active global health programs. Crosscampus<br />

collaborations in global health are emerging, representing a new frontier<br />

<strong>of</strong> academic opportunity. In order to capitalize on this opportunity the campus<br />

is launching a <strong>UCLA</strong>-wide Global <strong>Health</strong> Initiative; I have been asked to chair<br />

the steering committee.<br />

To support the campus-wide effort, in which I expect our school to play a<br />

central role, and to further implement one <strong>of</strong> our school’s strategic goals to build<br />

a world-class global health presence, I am pleased to announce the appointment<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dr. Onyebuchi Arah, associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor in the Department <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology,<br />

as the first associate dean for global health. You can read more about Dr. Arah’s<br />

appointment on page 33.<br />

Finally, I’m pleased to share that we have an exciting year ahead <strong>of</strong> us.<br />

In 2011, the <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> celebrates its 50th. We plan to spend the<br />

year celebrating our past, present and future.<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> us have a vague recollection <strong>of</strong> what life was like in the early<br />

1960s, and for those who don’t, the TV show Mad Men reminds us <strong>of</strong> a few<br />

critical changes we’ve seen since the school was founded in 1961. Long gone<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

2 0 0 9 - 1 0 D E A N ’ S<br />

A DV I S O RY B OA R D<br />

3<br />

are the days <strong>of</strong> the three-martini lunch, smoke-filled <strong>of</strong>fice and advertising<br />

campaigns to convince smokers to keep on puffing. Fifty years ago cars were<br />

not required to have seat belts and the notion <strong>of</strong> a child restraint system was<br />

your mother’s arm flung across your chest. It would be 20 years until the first<br />

positive case <strong>of</strong> HIV/AIDS in the United States was reported to the Centers for<br />

Disease Control.<br />

It was into this environment that the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> was<br />

born. As part <strong>of</strong> an institution consistently rated among the top schools <strong>of</strong><br />

public health in the country, our faculty, students and alumni have led the way<br />

in improving the quality <strong>of</strong> life and longevity for people across the globe.<br />

I would like to personally invite all <strong>of</strong> you – our alumni, friends, faculty,<br />

staff and students – to join us in celebrating the enormous contribution we have<br />

made, as well as our potential for even greater contributions in the years ahead.<br />

Whether you join us online for our new webinar series (see page 32), join us<br />

at the 50th Anniversary Gala, or simply provide your updated information for<br />

the alumni directory, let us hear from you this year. You are the reason for our<br />

success, and the key to our ability to continue to make a difference in the health<br />

<strong>of</strong> populations locally and globally. Thank you for being part <strong>of</strong> something great.<br />

Ira R. Alpert *<br />

Lester Breslow<br />

Sanford R. Climan<br />

Edward A. Dauer<br />

Deborah Kazenelson Deane*<br />

Michele DiLorenzo<br />

Samuel Downing*<br />

Robert J. Drabkin<br />

Gerald Factor (Vice Chair)<br />

Jonathan Fielding<br />

Dean Hansell (Chair)<br />

Cindy Harrell Horn<br />

Stephen W. Kahane *<br />

Carolyn Katzin *<br />

Carolbeth Korn *<br />

Jacqueline B. Kosec<strong>of</strong>f<br />

Kenneth E. Lee *<br />

Edward J. O’Neill *<br />

Thomas Priselac<br />

Monica Salinas<br />

Fred W. Wasserman *<br />

Pamela K. Wasserman *<br />

Thomas Weinberger<br />

Cynthia Sikes Yorkin<br />

*SPH Alumni<br />

Linda Rosenstock, M.D., M.P.H.<br />

Dean<br />

TOTAL REVENUES<br />

Grants and Contracts<br />

State-Generated Funds<br />

Gifts and Other<br />

Fiscal Year 09-10<br />

$70.5 million<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

4<br />

POOR ORAL<br />

<strong>HEALTH</strong> HAS BEEN<br />

CALLED A “SILENT<br />

EPIDEMIC,” WITH<br />

DISPARITIES AND<br />

ACCESS PROBLEMS<br />

CALLING FOR MORE<br />

ATTENTION FROM<br />

PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>.<br />

WISDOM ON TEETH:<br />

A Growing Focus<br />

on Dental Care Needs<br />

Few public health issues have received<br />

more attention in recent years than lack <strong>of</strong> access to essential medical services<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

“Oral health<br />

issues fit so<br />

closely with<br />

public health’s<br />

mission, and<br />

through efforts<br />

aimed at prevention, education and<br />

addressing access issues, we have<br />

the potential to get more in return<br />

from our investment than from<br />

many other investments.”<br />

—Dr. Ronald Andersen<br />

and its disproportionate effect on certain population groups. Meanwhile, a parallel<br />

issue has gone relatively unnoticed.<br />

“Access problems appear to be considerably greater with respect to oral<br />

health services than general health services, and the disparities by income and<br />

minority status are probably larger,” says Dr. Ronald Andersen, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health<br />

services at the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>. “But because dental care isn’t<br />

associated with saving lives, it hasn’t been emphasized in public health to the<br />

extent that it should be.”<br />

Overall, oral health has improved dramatically in the United States over<br />

the last half-century, thanks in part to public health efforts such as fluoridation<br />

<strong>of</strong> drinking water and education about the benefits <strong>of</strong> fluoride toothpaste. It<br />

wasn’t long ago that the majority <strong>of</strong> Americans lost their teeth by middle age;<br />

today, most can expect to retain their natural teeth over their lifetimes.<br />

But there is significant cause for concern. A decade ago, in the first-ever<br />

Surgeon General’s report on oral health, Dr. David Satcher pointed to a “silent<br />

epidemic” <strong>of</strong> dental and oral diseases with “pr<strong>of</strong>ound disparities that affect those<br />

without the knowledge or resources to achieve good oral care.” In addition,<br />

although dental care might not seem as critical as medical care, poor oral health<br />

can cause significant problems…and can be related to health ailments outside

the mouth. Untreated, tooth decay (cavities) – the<br />

most common chronic disease in children – can<br />

cause everything from pain and difficulty eating to<br />

lost school and work time. Serious oral disorders can<br />

undermine self-esteem, inhibiting children and adults<br />

from smiling. Gum disease has recently been linked<br />

in studies to increased risk for diabetes, heart disease<br />

and stroke.<br />

And while much attention has been paid to<br />

the problem <strong>of</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> health insurance, the fact<br />

that even more are without dental coverage is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

overlooked. Although public insurance programs<br />

such as Medicaid have increased coverage for children,<br />

dental benefits tend to be vulnerable to cuts in<br />

tough economic times. By the same token, for many<br />

low-income families struggling financially and, in<br />

some cases, lacking education about the importance<br />

<strong>of</strong> regular dental visits, dental care may be viewed<br />

as optional.<br />

“Oral health issues fit so closely with public<br />

health’s mission,” observes Andersen, “and through<br />

efforts aimed at prevention, education and addressing<br />

access issues, we have the potential to get more in<br />

return from our investment than from many other<br />

investments.”<br />

Dental public health issues haven’t been ignored<br />

at <strong>UCLA</strong>, where faculty in the <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong> and <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> Dentistry have worked – <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

together – to address some <strong>of</strong> the major concerns.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the key efforts began in 2001 when The<br />

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation provided funding<br />

for a national demonstration program aiming to<br />

reduce dental-care access disparities. Fifteen dental<br />

schools were selected to participate in the Dental<br />

Pipeline Program, which would receive additional<br />

funding from The California Endowment. The<br />

program’s national evaluation team was based in the<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>, with Andersen as<br />

the principal investigator and Dr. Pamela Davidson,<br />

associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health services at the school,<br />

as co-principal investigator. (The original project<br />

ended in 2007, but a follow-up study to measure its<br />

sustainability is ongoing.)<br />

The pipeline program was established in an<br />

effort to increase access to dental care in low-income<br />

and minority communities by recruiting more students<br />

from underrepresented minority groups to<br />

dental schools, improving dental school curricula to<br />

better prepare students to provide culturally competent<br />

care, and providing more clinical practice experiences<br />

for students in underserved communities.<br />

“If you look at the ethnicity <strong>of</strong> dentists compared to<br />

the distribution <strong>of</strong> the population, there are greater<br />

differences than in medicine,” Andersen notes. That<br />

has contributed in part to the shortage <strong>of</strong> oral health<br />

providers in minority communities, he says.<br />

Dental schools have faced significant challenges<br />

in their efforts to recruit minority students into<br />

dental careers, Andersen notes. For one, the shortage<br />

<strong>of</strong> providers in minority communities means there<br />

are few family members or friends serving as role<br />

models and mentors. Nonetheless, through steppedup<br />

efforts, including the establishment <strong>of</strong> pre-dental<br />

programs to assist students in meeting prerequisites,<br />

the pipeline program schools increased applications<br />

from underrepresented minority students by 77<br />

percent from 2003 to 2007, while enrollment <strong>of</strong><br />

underrepresented minority students increased by<br />

27 percent.<br />

Beyond the effort to increase the number <strong>of</strong><br />

minority dental providers, the pipeline program<br />

sought to revamp education and training experiences<br />

that would make all students more likely to consider<br />

careers in public health and service to underserved<br />

communities. While curricula were revised and the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> days senior dental students practiced<br />

in underserved communities increased, it’s unclear<br />

whether there was a corresponding increase in graduates<br />

going on to practice in these communities.<br />

Unfortunately, Andersen notes, dental students tend<br />

to enter practice with huge debts; thus, many who<br />

want to go into public service positions are deterred<br />

by the lower salaries and instead feel compelled to<br />

opt for private practice.<br />

The problem <strong>of</strong> disparities in utilization <strong>of</strong> dental<br />

services – particularly among children – is underscored<br />

by a recent study conducted by Dr. Nadereh<br />

Pourat, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health services and director <strong>of</strong><br />

research for the Center for <strong>Health</strong> Policy Research,<br />

which is based in the school. Using data from the<br />

2005 California <strong>Health</strong> Interview Survey, Pourat<br />

found that nearly 25 percent <strong>of</strong> California children<br />

ages 11 and under had never seen a dentist, and<br />

that among those who had, there were significant<br />

differences by race, ethnicity and type <strong>of</strong> insurance<br />

in the amount <strong>of</strong> time between dental care visits<br />

(see page 24).<br />

Having any kind <strong>of</strong> insurance significantly<br />

increased the odds that a child would see a dentist<br />

on a regular basis, but the type <strong>of</strong> coverage mattered:<br />

54 percent <strong>of</strong> privately insured children had seen<br />

a dentist within the previous six months, vs. 27<br />

percent <strong>of</strong> publicly insured children (Medicaid or<br />

the Children’s <strong>Health</strong> Insurance Program) and 12<br />

“<strong>Public</strong> programs<br />

are designed to<br />

improve access<br />

to care for<br />

underserved<br />

populations,<br />

and our study<br />

shows that they<br />

are successful<br />

in doing so.<br />

However,<br />

they don’t close<br />

the gap.”<br />

—Dr. Nadereh Pourat<br />

5<br />

feature <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

6<br />

An analysis <strong>of</strong> children<br />

who suffer the most from<br />

dental disease suggests<br />

it’s not only children<br />

from low-income families<br />

and underserved minority<br />

groups, but also those<br />

from families with<br />

what is referred to as<br />

low oral health literacy.<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

percent <strong>of</strong> children without any coverage. Even<br />

when taking into account only those with public<br />

insurance coverage, though, the study found that<br />

Latino and African-American children went to<br />

the dentist significantly less <strong>of</strong>ten than white and<br />

Asian-American children.<br />

“<strong>Public</strong> programs are designed to improve access<br />

to care for underserved populations, and our study<br />

shows that they are successful in doing so,” Pourat<br />

says. “However, they don’t close the gap. There is<br />

more work to do in addressing disparities in dental<br />

care for children.”<br />

Pourat suspects a key factor in the persistence<br />

<strong>of</strong> these disparities is that public insurance programs<br />

reimburse dentists at a lower level than private<br />

insurance. Unlike medical care, in which managed<br />

care and group practices encourage more providers<br />

to see patients in public programs, dental care is<br />

dominated by solo practitioners in private <strong>of</strong>fices –<br />

many <strong>of</strong> whom don’t see patients with public<br />

insurance. A study conducted by Pourat and colleagues<br />

in 2003 found that only about 40 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> California dentists accepted public-insurance<br />

patients. Coupled with the general shortage <strong>of</strong><br />

providers in low-income communities, this has<br />

posed a major barrier, and may be the reason many<br />

families choose to forgo care. Pourat has begun a<br />

new study, funded by the National Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Dental and Crani<strong>of</strong>acial Research, to examine the<br />

impact <strong>of</strong> the local supply <strong>of</strong> oral health providers<br />

on access to care.<br />

Addressing reimbursement inequities is one<br />

<strong>of</strong> several potential solutions that Pourat and others<br />

have proposed. Another is to strengthen the safety-<br />

net system by broadening the types <strong>of</strong> dental<br />

providers – including preparing other licensed pr<strong>of</strong>essionals,<br />

such as hygienists, who can deliver primary<br />

pediatric dental care. Pourat notes that many general<br />

dentists are uncomfortable delivering care to very<br />

young children, an issue that could be addressed in<br />

dental school training with more clinical experiences<br />

involving young patients.<br />

Pourat believes more education is needed for<br />

all families about the importance <strong>of</strong> dental visits<br />

and preventive oral health care in childhood. “Many<br />

parents figure it’s not that important because their<br />

children are going to lose their primary teeth anyway,”<br />

she says. “But the reality is that when you<br />

have a poor oral health environment, the problems<br />

are likely to continue when the secondary teeth<br />

come in. Teaching children good oral hygiene can<br />

have a major impact on their oral health as adults.”<br />

An analysis <strong>of</strong> children who suffer the most from<br />

dental disease suggests it’s not only children from<br />

low-income families and underserved minority<br />

groups, but also those from families with what is<br />

referred to as low oral health literacy, says Dr. James<br />

Crall, pr<strong>of</strong>essor and chair <strong>of</strong> pediatric dentistry in<br />

the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> Dentistry and a faculty member<br />

in the <strong>UCLA</strong> Center for <strong>Health</strong>ier Children, Families<br />

and Communities, based in the <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong>. “There are issues <strong>of</strong> culture, language, nutrition<br />

and use <strong>of</strong> health services that are amenable to<br />

public health as well as primary care approaches,”<br />

he explains.<br />

Crall has been a leader in dental public health<br />

for more than a decade. In 1997 he was appointed<br />

the first dental scholar-in-residence at the Agency for

<strong>Health</strong> Care Policy and Research and he has been actively involved in national,<br />

state and pr<strong>of</strong>essional oral health policy development ever since. From 2000<br />

to 2008 he was director <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Health</strong> Resources and Services Administration/<br />

Maternal and Child <strong>Health</strong> Bureau National Oral <strong>Health</strong> Policy Center, colocated<br />

within the Center for <strong>Health</strong>ier Children, Families and Communities.<br />

Crall also directs a pediatric dentistry leadership training program in collaboration<br />

with other members <strong>of</strong> the center’s faculty. Since 2007 he has been project<br />

director <strong>of</strong> the American Academy <strong>of</strong> Pediatric Dentistry’s Head Start Dental<br />

Home Initiative, which is building networks <strong>of</strong> providers in every state to<br />

improve access to dental services for children in Head Start programs.<br />

Crall, who was part <strong>of</strong> Andersen’s national evaluation team for the Dental<br />

Pipeline Program, believes public health efforts to address the current challenges<br />

in oral health require a combination <strong>of</strong> innovative training initiatives and community<br />

programs, along with policies that effect change in the practice environment,<br />

such as increased reimbursement and other incentives to work with underserved<br />

populations.<br />

The subspecialty area <strong>of</strong> dental public health is small, Crall notes; it will<br />

take more than dentists to make a difference. “We need to encourage more dentists<br />

to go into public health, but we also must find ways to foster collaborations<br />

with non-dentists in public health and medicine,” he says. “That’s now occurring<br />

at <strong>UCLA</strong> in a way that we haven’t seen before, and it’s a goal that has gained<br />

increasing recognition at the national level.”<br />

M.P.H. Degree Informs Her Effort to<br />

Organize American Indian Dentists<br />

Nowhere are oral health problems more severe than among American Indians. The last<br />

survey by the Indian <strong>Health</strong> Service (IHS), published in 1999, found that 87 percent <strong>of</strong><br />

American Indian children ages 6-14 and 91 percent <strong>of</strong> 15-19 year olds had a history <strong>of</strong><br />

tooth decay. Seventy-eight percent <strong>of</strong> adults ages 35-44 and 98 percent <strong>of</strong> those 55 and<br />

older had lost at least one tooth because <strong>of</strong> dental decay, gum disease or oral trauma.<br />

Dr. Ruth Bol (M.P.H. ’09), a pediatric dentist in private practice in Menifee, Calif.,<br />

who is herself American Indian, is drawing on her <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong><br />

education to organize American Indian dentists in response to the problem. Bol worked<br />

four years with the IHS (part <strong>of</strong> the U.S. <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Service) and became frustrated<br />

with the lack <strong>of</strong> leadership, which she believed had much to do with the scarcity <strong>of</strong><br />

American Indians among the dentists practicing on the reservations.<br />

So she worked her way up the ranks <strong>of</strong> the Society <strong>of</strong> American Indian Dentists<br />

(Bol is currently vice president), was elected to the California Dental Association board<br />

<strong>of</strong> directors and became active in the American Dental Association. Realizing the value<br />

a public health education could bring, Bol enrolled at <strong>UCLA</strong> for both her pediatric dentistry<br />

residency and M.P.H. from the <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>. With a grant she wrote in one <strong>of</strong><br />

her <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> courses, Bol secured funding from Delta Dental <strong>of</strong> California<br />

to support the Society <strong>of</strong> American Indian Dentists’ efforts to mentor American Indians<br />

before, during and after dental school. She is currently meeting with other potential<br />

funders.<br />

“The more I got involved with these big-picture issues, the more I realized there<br />

was a lot I didn’t know,” Bol says. “Getting the M.P.H. has given me credibility as well<br />

as knowledge on everything from developing and evaluating programs to writing grants.<br />

It’s provided me with the tools to work with underserved communities.”<br />

Ruth Bol, D.D.S. M.P.H. ’09<br />

7<br />

feature <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

8<br />

SHE IS<br />

WORKING WITH<br />

THE CONGOLESE<br />

TO BUILD A<br />

DISEASE<br />

SURVEILLANCE<br />

SYSTEM THAT<br />

HAS ALREADY<br />

REVEALED THE<br />

SURPRISINGLY<br />

DRAMATIC GROWTH<br />

OF HUMAN<br />

MONKEYPOX.<br />

ANNE RIMOIN:<br />

Bringing Emerging Diseases<br />

Above the Radar<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

Although her specific focus is studying the epidemiology <strong>of</strong> human<br />

monkeypox in the Democratic Republic <strong>of</strong> the Congo (DRC), Dr. Anne Rimoin also has an eye on the<br />

bigger picture: working with the Congolese government and local investigators to develop an infrastructure<br />

that will enable the Central African nation to conduct proper surveillance <strong>of</strong> all emerging infectious diseases.<br />

“To me, if you’re a researcher working in a low-resource setting, you have a moral obligation not just to<br />

collect your data and leave, but to build capacity and collaborate with the people who, by their good graces,<br />

are allowing you to do this work in their country,” she says.<br />

Over the last six years, Rimoin, assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> epidemiology at the school, has established a<br />

research site in central DRC that now serves as headquarters for a variety <strong>of</strong> studies <strong>of</strong> cross-species transmission<br />

<strong>of</strong> disease. Heading an all-Congolese team, Rimoin collaborates closely with the DRC Ministry <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong>, the Kinshasa <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> and the National Laboratory to improve disease surveillance<br />

capacity in a nation that is one <strong>of</strong> the world’s poorest, and has been devastated by civil war. “There is a long<br />

way to go – what we’ve done so far represents just a drop in the bucket – but I’m pleased just to be able<br />

to contribute as I can,” Rimoin says.<br />

Already, though, Rimoin and her Congolese collaborators have produced tangible evidence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

critical nature <strong>of</strong> building a disease surveillance infrastructure. In August, they published the first results<br />

<strong>of</strong> their human monkeypox study in the Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the National Academy <strong>of</strong> Science, showing that rates<br />

<strong>of</strong> the disease had increased by an astounding 20-fold in the DRC since 1980.

Ironically, Rimoin’s group noted, one <strong>of</strong> public<br />

health’s greatest success stories opened the door for<br />

the dramatic increase. The eradication <strong>of</strong> smallpox,<br />

announced in 1980, spelled the end <strong>of</strong> a vaccination<br />

program that had also provided protective immunity<br />

against monkeypox, a related virus believed to be<br />

carried primarily by squirrels and other rodents.<br />

(Although generally less lethal than smallpox,<br />

monkeypox can cause serious symptoms, including<br />

severe eruptions on the skin, fever, headaches,<br />

swollen lymph nodes and, in some cases, blindness<br />

and death.) Particularly in rural areas, where displaced<br />

populations rely to a greater extent on bushmeat, the<br />

growing number <strong>of</strong> unvaccinated individuals over<br />

time led to a gradual increase in the rate <strong>of</strong> infection.<br />

But in the absence <strong>of</strong> any surveillance, Rimoin notes,<br />

monkeypox “fell under the radar.” (For more on the<br />

study, see page 23.)<br />

Growing up in Los Angeles, Rimoin always had<br />

positive associations with Africa. In a home adorned<br />

with African art, her father would recall fondly his<br />

research experiences working with a Pygmy population<br />

in the Central African Republic. At Middlebury<br />

College in Vermont, Rimoin earned her undergraduate<br />

degree in African History. It was only after graduating<br />

and going into the Peace Corps that she became<br />

interested in science, and particularly epidemiology.<br />

In Benin, West Africa, Rimoin spent two years as a<br />

volunteer coordinator for the guinea worm eradication<br />

effort. “It was a perfect public health program<br />

that taught me to do disease surveillance,” she says.<br />

“It really brought home the importance <strong>of</strong> using<br />

basic epidemiologic methods to solve a problem.”<br />

Upon completing the program, Rimoin enrolled<br />

at the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>, where she<br />

received her M.P.H. in 1996. For her internship<br />

she worked in Nepal doing disease surveillance for<br />

the World <strong>Health</strong> Organization’s polio eradication<br />

program. Rimoin was then hired by the WHO as a<br />

logistics <strong>of</strong>ficer, assisting in the expanded polio surveillance<br />

and eradication program in Ethiopia and<br />

Eretria. She also initiated a collaborative relationship<br />

between the WHO and the Peace Corps, including<br />

development <strong>of</strong> a program and training materials for<br />

health-oriented Peace Corps volunteers to carry out<br />

disease surveillance activities in Africa and Nepal.<br />

After completing her Ph.D. at the Johns Hopkins<br />

Bloomberg <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> in 2003, Rimoin<br />

worked as a program scientist for the National<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Child <strong>Health</strong> and Human Development,<br />

coordinating clinical studies in Africa. While at a<br />

meeting at the DRC Ministry <strong>of</strong> <strong>Health</strong>, she was<br />

part <strong>of</strong> a discussion in which it was noted that there<br />

had been an increase in reported cases <strong>of</strong> human<br />

monkeypox in the country. Rimoin’s interest was<br />

piqued. “It made sense to me that given the lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> infrastructure and absence <strong>of</strong> disease surveillance,<br />

if there were any significant reports <strong>of</strong> monkeypox<br />

out there it was likely a much bigger problem than<br />

anyone was anticipating,” she says. Rimoin promptly<br />

proposed to head the first epidemiologic study<br />

assessing the burden <strong>of</strong> human monkeypox in<br />

DRC, and received funding to begin setting up<br />

her program in 2004.<br />

Ever since, Rimoin and her team have been training<br />

local health workers in identifying and reporting<br />

cases as well as interviewing monkeypox patients to<br />

learn about their potential exposures. The workers<br />

collect biological samples that are transported to the<br />

project’s field station and then to Kinshasa, as well<br />

as to collaborators in the United States who conduct<br />

laboratory analyses and report back to the Congolese<br />

field workers.<br />

One reason the DRC was in such dire need<br />

<strong>of</strong> a disease surveillance program is that there are<br />

tremendous logistical challenges to implementing<br />

one. From the beginning, Rimoin’s team has faced<br />

problems such as how to collect and preserve biological<br />

specimens in settings that <strong>of</strong>ten lacked electricity,<br />

running water and refrigeration sources. A<br />

country <strong>of</strong> 900,000 square kilometers has only about<br />

300 kilometers worth <strong>of</strong> roads. Given the expense<br />

<strong>of</strong> gasoline and the DRC’s scarce economic resources,<br />

cost is never far from Rimoin’s mind. “Our supervisors<br />

have motorcycles, but for day-to-day surveillance<br />

we give our health care workers bicycles so they can<br />

take supplies from the headquarters to their village,”<br />

she says. “That can be as many as 200-300 kilometers<br />

away, but it’s a sustainable approach.”<br />

At the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>, where<br />

she has been a member <strong>of</strong> the faculty since 2004,<br />

Rimoin teaches her students the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

working with local collaborators, understanding the<br />

socio-cultural and political context in which problems<br />

occur, and designing and implementing interventions<br />

that are practical and feasible, particularly in lowresource<br />

settings. “Emerging infectious diseases are<br />

definitely out there,” she says. “You just need to<br />

identify the populations at the highest risk and<br />

make sure you’re asking the right questions or you’re<br />

going to miss important events that signal the early<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> a disease.”<br />

Rimoin, who spends roughly a third <strong>of</strong> her time<br />

working in the field in the DRC, is committed to<br />

being there for the long haul. “My goal is sustainable<br />

research,” she says. “I am fully invested in my work<br />

in the DRC and intend to have a long relationship<br />

with my Congolese collaborators.”<br />

“It made<br />

sense to me<br />

that given<br />

the lack <strong>of</strong><br />

infrastructure<br />

and absence<br />

<strong>of</strong> disease<br />

surveillance,<br />

if there were<br />

any significant<br />

reports <strong>of</strong><br />

monkeypox<br />

out there it<br />

was likely a<br />

much bigger<br />

problem than<br />

anyone was<br />

anticipating.”<br />

—Dr. Anne Rimoin<br />

9<br />

faculty pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

10<br />

A <strong>BROADER</strong><br />

Policies in All Sectors<br />

Make a Difference<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

AS MOMENTUM<br />

BUILDS FOR<br />

CONSIDERING THE<br />

PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

EFFECTS OF<br />

DECISIONS<br />

OUTSIDE <strong>HEALTH</strong>’S<br />

TRADITIONAL<br />

PURVIEW, SPH<br />

FACULTY ARE<br />

LEADING THE WAY.<br />

Although the details were much debated during the<br />

year-long politicking over health care reform, no one would disagree that there<br />

were major health implications to the bills under consideration – and ultimately<br />

to the law passed in Congress and signed by President Obama last March.<br />

But what about debates over alternative energy, agricultural subsidies, and<br />

even extending the Bush tax cuts? Few would call these health issues…yet their<br />

potential impact on health is pr<strong>of</strong>ound. Similarly, it might seem outside <strong>of</strong><br />

health’s purview when municipalities consider mass-transit systems or major<br />

commercial developments – but whether an urban environment is conducive to<br />

safely walking and biking can go a long way toward determining the health <strong>of</strong> the<br />

local population. When public schools face massive budget reductions there is<br />

concern, rightfully, about the effects on education. But this, too, is a health issue:<br />

With physical education and other health-promoting school programs becoming<br />

vulnerable, those reductions ultimately affect obesity and children’s health. And<br />

formal education is a major determinant <strong>of</strong> longevity.<br />

Dr. Jonathan Fielding, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health services at the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> and director <strong>of</strong> the Los Angeles County Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong>, is among the leaders <strong>of</strong> a growing movement to consider health impacts<br />

across a wider range <strong>of</strong> societal discussions – a movement known as <strong>Health</strong> in<br />

All Policies. “If you look at what determines health in populations, as well as<br />

disparities in health between communities, to a considerable extent it has to do<br />

with the social and physical environment – the societal underpinnings that are<br />

typically considered issues <strong>of</strong> economic development, education, transportation<br />

and housing, to name a few, but not health issues,” Fielding says.<br />

But Fielding concluded long ago that even prevention-oriented strategies by<br />

health departments to reduce health risk factors – though <strong>of</strong> great importance –<br />

fail to address major conditions that affect health in less-than-obvious ways.<br />

“We’ve gotten too used to segregating issues by sector,” he says. “We have to do<br />

a better job crossing over and working with people in other sectors to help them<br />

understand the effects <strong>of</strong> their decisions – whether it’s decisions on subsidizing<br />

high-fructose corn syrup production or decisions on how much is invested in the

11<br />

<strong>VIEWOF</strong> <strong>HEALTH</strong>:<br />

highway system as opposed to bikeable and walkable<br />

cities and mass transit-oriented development.”<br />

In the same way that <strong>Health</strong> in All Policies<br />

requires educating leaders in non-health agencies<br />

about the health consequences <strong>of</strong> decisions, it also<br />

calls for more broadly trained public health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals,<br />

contends Dr. Richard Jackson, chair and<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> environmental health sciences at the<br />

school and, like Fielding, a national leader in promoting<br />

the <strong>Health</strong> in All Policies concept. “It’s clear<br />

that if you’re graduating from a school <strong>of</strong> public<br />

health, you should have at least a basic familiarity<br />

with issues such as housing, engineering and economics,”<br />

says Jackson, who has served as California’s<br />

state health <strong>of</strong>ficer and as director <strong>of</strong> the National<br />

Center for Environmental <strong>Health</strong>, part <strong>of</strong> the U.S.<br />

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.<br />

With passage <strong>of</strong> health care reform earlier<br />

this year came tangible evidence that the voices <strong>of</strong><br />

Fielding, Jackson and other public health leaders<br />

at <strong>UCLA</strong> and elsewhere are being heard when it<br />

comes to their argument that health impacts should<br />

be considered in a broader array <strong>of</strong> policy decisions.<br />

The law created the National Prevention, <strong>Health</strong><br />

Promotion, and <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Council, composed<br />

<strong>of</strong> top government <strong>of</strong>ficials, to elevate and coordinate<br />

prevention activities and design a national<br />

prevention and health promotion strategy in conjunction<br />

with communities across the country.<br />

Chaired by the U.S. surgeon general, it includes<br />

the secretaries <strong>of</strong> Agriculture, Labor, <strong>Health</strong> and<br />

Human Services, Education, and Homeland Security;<br />

the administrator <strong>of</strong> the Environmental Protection<br />

Agency; the chair <strong>of</strong> the Federal Trade Commission;<br />

and the director <strong>of</strong> the National Drug Control<br />

Policy, among others.<br />

The movement is catching on at the state<br />

and local levels as well. In California, the state<br />

health department has established a <strong>Health</strong> in All<br />

Policies Task Force as part <strong>of</strong> the governor’s Strategic<br />

Growth Council. In Los Angeles County, Fielding’s<br />

department conducted a health impact assessment<br />

outlining the potential benefits <strong>of</strong> a proposed<br />

restaurant nutritional menu-labeling law in addressing<br />

the obesity epidemic. The assessment is believed<br />

to have played a key role in the passage <strong>of</strong><br />

California’s first-in-the-nation menu-labeling law<br />

in 2008, which in turn led to the inclusion <strong>of</strong><br />

menu labeling in the federal health reform law.<br />

When public schools face<br />

budget reductions, it’s also<br />

a health issue: Physical education<br />

is jeopardized, and formal education<br />

is related to longevity.<br />

cover story <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

12<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

“If you look<br />

at what<br />

determines health<br />

in populations,<br />

to a considerable<br />

extent it has<br />

to do with<br />

the societal<br />

underpinnings<br />

that are typically<br />

considered<br />

issues <strong>of</strong><br />

economic<br />

development,<br />

education,<br />

transportation<br />

and housing,<br />

to name a few,<br />

but not health<br />

issues.”<br />

—Dr. Jonathan Fielding<br />

The idea <strong>of</strong> viewing health more broadly isn’t<br />

new – in fact, Fielding notes, in some ways <strong>Health</strong><br />

in All Policies harkens back to an earlier time for<br />

the public health field. “You would see health effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> malnutrition, or <strong>of</strong> poor housing and inadequate<br />

sanitation, and the effects <strong>of</strong> investments in other<br />

sectors on health and health disparities were obvious,”<br />

he says. The United States fell behind other<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> the developed world – particularly Europe,<br />

which has used the health impact assessment (HIA)<br />

as a widespread policy-making tool for some time.<br />

But in the last decade, the concept has gained<br />

momentum – with the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong> playing an important leadership role.<br />

Jackson, while serving as the director <strong>of</strong> CDC’s<br />

environmental health center in the late 1990s, was<br />

among the first to advocate for including assessment<br />

<strong>of</strong> health impact in major policy deliberations.<br />

He notes that since passage <strong>of</strong> the National<br />

Environmental Policy Act in 1969, major federal<br />

projects have required environmental impact<br />

assessments; at the state level, the California<br />

Environmental Quality Act passed the following<br />

year, requiring environmental impact reports for<br />

projects with potentially significant environmental<br />

effects. Although the environmental studies that take<br />

place as part <strong>of</strong> the state and federal mandates <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

give a nod toward health impacts, thorough public<br />

health assessments for proposed policies are rare.<br />

As a result, “you can have a significant project that’s<br />

outlining what will happen to endangered species<br />

but <strong>of</strong>fering little analysis <strong>of</strong> what happens to<br />

children, old people, poor people and everyone<br />

Transportation<br />

safety issues are also<br />

community health issues:<br />

Airports present<br />

potential noise and air<br />

quality concerns for the<br />

local population.<br />

in between,” says Jackson, who is currently chairing<br />

an Institute <strong>of</strong> Medicine committee, “A Framework<br />

and Guidance for <strong>Health</strong> Impact Assessment,” on<br />

which Fielding also serves.<br />

Recent U.S. history is replete with examples <strong>of</strong><br />

major undertakings that would have benefited from<br />

advance consideration <strong>of</strong> health impacts, Jackson<br />

says, starting with the Interstate Highway System,<br />

an enormous expenditure undertaken by the federal<br />

government in the 1950s. “We know the built environment<br />

has major health impacts, from respiratory<br />

diseases and injuries to obesity and many other<br />

chronic diseases,” he says, “and yet transportation and<br />

other sister agencies are scarcely aware <strong>of</strong> them.”<br />

In 2001, Fielding brought together a group <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> faculty to begin a<br />

joint endeavor with the Washington, D.C.-based<br />

Partnership for Prevention. With support from the<br />

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>Health</strong><br />

Impact Assessment Project aimed to assess the<br />

feasibility <strong>of</strong> HIAs and develop prototypes, applied<br />

to specific policies. Starting by evaluating the health<br />

impacts on the Los Angeles City Living Wage<br />

Ordinance, the group crossed traditional boundaries<br />

within public health as well as seeking out<br />

researchers in other fields. “With a lot <strong>of</strong> these issues,<br />

we don’t start with inherent expertise in the subject<br />

matter,” Fielding explains. “We need to partner with<br />

experts from other fields and use resources from<br />

other disciplines to determine how changes in different<br />

sectors positively or negatively affect health.”<br />

While the HIA tradition in Europe had emphasized<br />

bringing stakeholder communities into the<br />

process <strong>of</strong> decisions with potential health consequences,<br />

the <strong>UCLA</strong> team developed methods that<br />

are more quantitative. “We wanted to show through

<strong>Health</strong> Impact Assessment <strong>of</strong> Santa Monica Airport Teaches<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> Pediatric Residents to Broaden View <strong>of</strong> Physician’s Role<br />

For the pediatric residents training at Ronald Reagan<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> Medical Center, it was an unusual project – but one<br />

that reflects a recognition that social and environmental<br />

conditions are every bit as important to children’s health<br />

as what occurs in a clinical setting.<br />

In response to concerns from members <strong>of</strong> the community<br />

surrounding Santa Monica Airport, the 10 pediatric<br />

residents – part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>UCLA</strong> Community <strong>Health</strong> and<br />

Community leaders meet with <strong>of</strong>ficials to discuss concerns<br />

about potential health impacts from Santa Monica Airport.<br />

Advocacy Training (CHAT) program – conducted a health<br />

impact assessment (HIA) <strong>of</strong> the Santa Monica Airport to<br />

organize, analyze and summarize existing information on<br />

the potential health impacts <strong>of</strong> the airport’s activity related<br />

to three issues: air quality, noise and the lack <strong>of</strong> an airport<br />

buffer zone.<br />

“Pediatricians increasingly recognize that environmental<br />

health is actually closer to pediatrics than it is to<br />

adult medicine, and that we need to set environmental<br />

standards to protect kids because their exposures are<br />

much higher per pound <strong>of</strong> body weight than adults,” says<br />

Dr. Richard Jackson, chair and pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> environmental<br />

health sciences at the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> and<br />

a pediatrician who has specialized in the issue <strong>of</strong> children<br />

and environmental health. Jackson, who was brought in<br />

to teach part <strong>of</strong> the course, is also a longtime proponent<br />

<strong>of</strong> the need to assess proactively the impacts on health<br />

<strong>of</strong> transportation, construction, and other major decisions.<br />

The residents conducted what’s known as a rapid<br />

non-participatory HIA over two weeks last February.<br />

Their analysis was based on reviews <strong>of</strong> relevant scientific<br />

publications; regulations and guidance relevant to airport<br />

planning and health; input from expert consultants; public<br />

comment and testimony; and participation in community<br />

forums and meetings. The group concluded, among other<br />

things, that there has been a rise in the number <strong>of</strong> jet<br />

plane operations in recent decades, potentially increasing<br />

the air and noise pollution exposure in the surrounding<br />

area. The report noted that the airport’s proximity to<br />

schools, daycare centers, parks and residential homes<br />

may pose certain health risks for children and families<br />

living in the nearby community. The HIA <strong>of</strong>fered recommendations<br />

for mitigating the potentially adverse health<br />

impacts.<br />

Whether the recommendations are acted on remains<br />

to be seen, but the effort did not go unnoticed. “It had a<br />

huge political impact,” says Ping Ho (M.P.H. ’05), a Santa<br />

Monica resident who is a member <strong>of</strong> Concerned Residents<br />

Against Airport Pollution and Friends <strong>of</strong> Sunset Park<br />

Airport Committee, two grassroots groups that have<br />

lobbied the City <strong>of</strong> Santa Monica and airport <strong>of</strong>ficials on<br />

airport-related concerns. “They showed the community<br />

and our elected <strong>of</strong>ficials that the problem is <strong>of</strong> concern to<br />

front-line medical pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, and their summary made<br />

it clear that there is sufficient science to justify the concerns<br />

<strong>of</strong> the community.” Drawing on her own education<br />

in the school’s M.P.H. for <strong>Health</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essionals Program<br />

in Community <strong>Health</strong> Sciences, Ho has synthesized<br />

scientific studies and written briefings for the communitybased<br />

group.<br />

“Medical practitioners haven’t been very involved<br />

in HIAs to this point,” says Brian Cole (M.P.H. ’90, Dr.P.H.<br />

’03), a researcher at the school who has been a leader in<br />

the HIA movement as part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>UCLA</strong> HIA Project, and<br />

who served as a consultant to the pediatric residents.<br />

“It was exciting to see that the pediatric training program<br />

recognized the importance <strong>of</strong> learning about some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

upstream determinants <strong>of</strong> health problems and using the<br />

HIA as a way <strong>of</strong> addressing that.”<br />

Dr. Alma Guerrero (M.P.H. ’08), an assistant clinical<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> pediatrics and CHAT program faculty member,<br />

believes the pediatric residents benefited as much as the<br />

community. “What we try to instill in the residents is the<br />

importance <strong>of</strong> thinking broadly about health,” she says.<br />

“The Santa Monica Airport is near where a lot <strong>of</strong> our<br />

patients live, and it’s easy to take it for granted. By having<br />

the residents review the science and engage with the<br />

community on an important health concern, we’re encouraging<br />

them to think outside the walls <strong>of</strong> the clinic in how<br />

they define their role as physicians.”<br />

“By having<br />

the residents<br />

review the<br />

science and<br />

engage with<br />

the community<br />

on an important<br />

health concern,<br />

we are<br />

encouraging<br />

them to think<br />

outside the<br />

walls <strong>of</strong><br />

the clinic.”<br />

—Dr. Alma Guerrero<br />

13<br />

cover story <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

14<br />

“We know the<br />

built environment<br />

has major health<br />

impacts, from<br />

respiratory<br />

diseases and<br />

injuries to obesity<br />

and many other<br />

chronic diseases,<br />

and yet<br />

transportation<br />

and other sister<br />

agencies are<br />

scarcely aware<br />

<strong>of</strong> them.”<br />

—Dr. Richard Jackson<br />

our HIAs that a more systematic approach would be a valuable tool in the policy<br />

process,” says Dr. Gerald Kominski, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health services at the school and<br />

a key member <strong>of</strong> the initial <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Impact Assessment Project team. “Our<br />

goal was to lay out the plausible downstream health effects <strong>of</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong> initiatives<br />

or laws that might be enacted, casting as broad a net as possible to show<br />

that virtually all public programs have potential health consequences.”<br />

The <strong>UCLA</strong> group also argued for bringing in an evidence base. “It’s a twostep<br />

process,” Kominski explains. “The first is analytical – mapping out the possible<br />

pathways by which a policy can affect health. But the second important step<br />

is to say whether there is scientific evidence showing that these plausible effects<br />

have been measured. And the answer is that there is a lot <strong>of</strong> literature out there.”<br />

For an HIA <strong>of</strong> California’s Proposition 49, a successful 2002 ballot initiative to<br />

significantly expand state funding <strong>of</strong> after-school programs, the <strong>UCLA</strong> researchers<br />

found substantial evidence – in the education literature – that providing targeted<br />

after-school programs for at-risk children confers secondary health benefits, from<br />

increased physical activity and improved mental health to lower rates <strong>of</strong> substance<br />

abuse, teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Unfortunately,<br />

notes Kominski, the initiative wasn’t designed to address the challenges facing<br />

these at-risk children.<br />

In recent years, one leader in the HIA movement at <strong>UCLA</strong> and nationally<br />

has been Brian Cole (M.P.H. ’90, Dr.P.H. ’03), a researcher in the school’s<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Services who was hired as the team’s original project<br />

director while he was a doctoral student in the Department <strong>of</strong> Community<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Sciences. Cole has led the effort to create the HIA Clearinghouse<br />

Learning and Information Center (www.hiaguide.org). In addition to providing<br />

a single online location for all ongoing and completed HIAs in the United States,<br />

the clearinghouse provides links to research used to inform the HIAs and presents<br />

different methods for preparing an HIA. “One <strong>of</strong> our goals is to lower the<br />

bar, particularly for smaller agencies, so that they can do these more easily,”<br />

Cole explains.<br />

Meanwhile, Cole has continued to contract with municipalities and community<br />

groups to conduct HIAs. He recently served as a consultant on an HIA <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Santa Monica Airport done by a group <strong>of</strong> pediatric residents at <strong>UCLA</strong>’s David<br />

Geffen <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medicine (see the sidebar on page 13). With funding from the<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

Agricultural policies can<br />

affect health by, for instance,<br />

subsidizing high-fructose corn syrup –<br />

and indirectly fueling the obesity<br />

epidemic.

Pew Charitable Trust, Cole and his <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> colleagues are working to ensure<br />

that health concerns are addressed in the environmental<br />

impact report for the Wilshire Corridor<br />

Transit Alternatives – the so-called Subway-to-the-<br />

Sea proposed to be built on Los Angeles’ Westside.<br />

Beyond addressing health concerns, Cole says, the<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> group is seeking to maximize potential health<br />

benefits from the development: how, for instance,<br />

the system might be able to tap into existing pedestrian<br />

and bicycle routes to encourage people to<br />

walk and bike more. In addition, with funding from<br />

Robert Wood Johnson Active Living Research, the<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> group is conducting rapid HIAs around<br />

physical activity in schools.<br />

HIAs related to proposed developments – from<br />

a new shopping center to a new highway or subway<br />

system – are a natural fit, Cole explains, since they<br />

can be coupled with environmental impact assessments.<br />

But he and others have also been grappling<br />

with the more challenging but no-less-important<br />

type <strong>of</strong> HIA, ones attached to policies that don’t<br />

involved bricks-and-mortar projects. “The question<br />

is how we get people thinking about the upstream<br />

determinants <strong>of</strong> public health in labor, energy or<br />

agricultural policies, for example,” Cole says.<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> the work <strong>of</strong> the <strong>UCLA</strong> HIA project<br />

has involved building the tools and evidence base<br />

for agencies to apply to these population-level HIAs.<br />

In 2008, Cole and Fielding co-wrote a white paper<br />

published by the Partnership for Prevention on how<br />

Congress and federal agencies could incorporate<br />

HIAs into large-scale policy-making (“Building<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Impact Assessment Capacity: A Strategy<br />

for Congress and Government Agencies”).<br />

Beyond the formal processes <strong>of</strong> analyzing<br />

the potential impacts <strong>of</strong> a project or policy, Cole<br />

Promoting decent,<br />

affordable housing<br />

reduces problems<br />

associated with allergens,<br />

increases community<br />

stability and improves<br />

mental health,<br />

to name a few.<br />

explains, the HIA as well as other tools can play<br />

a broader role by simply educating the public and<br />

policy-makers about the connections between decisions<br />

that are not primarily about health and their<br />

potential public health impacts.<br />

Indeed, notes Fielding, the HIA isn’t an end<br />

in itself. “The HIA is a tool for operationalizing and<br />

concretizing the <strong>Health</strong> in All Policies concept,” he<br />

says. “But it does nothing unless it’s coupled with<br />

efforts to use that information to educate those<br />

who are making policy about why they should pay<br />

more attention to the health impacts <strong>of</strong> decisions<br />

in other sectors.”<br />

Kominski points out that the <strong>Health</strong> in All<br />

Policies movement is based on a notion that has long<br />

been recognized in public health – and championed<br />

by <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> faculty including<br />

Dr. Lester Breslow, dean emeritus <strong>of</strong> the school.<br />

“In public health we know that the medical care<br />

delivery system is just one determinant <strong>of</strong> the population’s<br />

health – an important component, but a<br />

relatively small one, especially when you consider<br />

the cost,” Kominski says. “There are also social<br />

determinants <strong>of</strong> health, and we are likely to reap<br />

much greater health improvements from investments<br />

in those areas than from additional medical<br />

care expenditures.”<br />

Fielding believes many outside <strong>of</strong> public health<br />

are beginning to come around to that point <strong>of</strong> view.<br />

“When we’re spending 50-100 percent more than<br />

our developed-country trading partners and doing<br />

worse in terms <strong>of</strong> health, it becomes obvious that<br />

we can’t just work through the medical care system<br />

to improve health,” he says. “We won’t move from<br />

being 37th in the world in life expectancy until the<br />

determinants <strong>of</strong> health and health impacts <strong>of</strong> decisions<br />

become a focus <strong>of</strong> public policy at all levels.”<br />

15<br />

cover story <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>

16<br />

WITH THE<br />

ONE-SIZE-FITS-ALL<br />

APPROACH A<br />

DISTANT MEMORY,<br />

EFFORTS TO<br />

CHANGE <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

BEHAVIORS ARE<br />

RELYING ON<br />

BETTER-TARGETED<br />

MESSAGES<br />

DELIVERED IN<br />

PROACTIVE AND<br />

INNOVATIVE WAYS.<br />

Higher Education:<br />

In the short video, a young couple has just returned<br />

late one evening from a party. Obviously inebriated, they are moving toward<br />

a sexual encounter. The scene ends and in the next shot it is morning. The<br />

camera zooms in on an unopened condom at the bedside, then shows the nowsober<br />

young man and young woman, appearing regretful as they reflect on a<br />

missed opportunity.<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong><br />

“There’s an appreciation<br />

that we need to challenge<br />

our traditional ways <strong>of</strong> thinking<br />

about how to do outreach<br />

to populations.”<br />

—Dr. Beatriz Solis<br />

The frankness <strong>of</strong> the HIV-prevention message targeting youth audiences<br />

would be notable anywhere, but what’s particularly striking about this one is<br />

that it was produced by high school students for their peers – in the Republic<br />

<strong>of</strong> Senegal, a predominantly Muslim nation in western Africa. Shot using mobile<br />

digital technology, it is one <strong>of</strong> many artistically produced peer-to-peer health<br />

messages made widely available to youth in several Senegal high schools and<br />

beyond through a specially created website, www.sunukaddu.com (“our<br />

voices” in Wol<strong>of</strong>).<br />

The project, which has involved two members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> faculty and several <strong>of</strong> their students, is one <strong>of</strong> many examples,<br />

both inside and outside the school, <strong>of</strong> innovative new approaches to health<br />

education. The days <strong>of</strong> relying on staid, top-down, one-size-fits-all messages are<br />

long gone, replaced by more dynamic, interactive communications, delivered<br />

in carefully selected settings in ways that resonate with the target audience.<br />

It’s a time <strong>of</strong> opportunity for the field <strong>of</strong> health education, says Beatriz<br />

Solis (M.P.H. ’96, Ph.D. ’07), director <strong>of</strong> healthy communities for the south

egion at The California Endowment. Solis notes,<br />

among other things, provisions in the new health<br />

care reform law call for increased education and<br />

engagement <strong>of</strong> linguistically diverse populations<br />

through community health workers. Funding for<br />

prevention that will become available under the<br />

new law will help to bolster the population-based<br />

perspective, including education. Next year will<br />

bring additional dollars to upgrade and expand<br />

community health centers and federally qualified<br />

health centers, providing new opportunities to<br />

reach populations that have traditionally been<br />

underserved by the health care system.<br />

At the same time, there has been a reexamination<br />

<strong>of</strong> traditional health education efforts.<br />

In some cases, Solis says, that has meant capitalizing<br />

on new technologies and communication<br />

approaches that enable communities to “own”<br />

their education – for example, through the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> social media in youth-oriented initiatives.<br />

In other cases, it has meant looking more broadly<br />

at social determinants <strong>of</strong> health problems and<br />

bringing in experts outside <strong>of</strong> the health arena<br />

to assist in the design and implementation <strong>of</strong><br />

initiatives.<br />

“We’re seeing much more crossing <strong>of</strong> traditional<br />

silos, as well as the building <strong>of</strong> relationships<br />

with leaders and organizations that have an ‘in’<br />

within communities and can help to build capacity,”<br />

Solis observes. “There’s an appreciation that we need<br />

to challenge our traditional ways <strong>of</strong> thinking about<br />

how to do outreach to populations.”<br />

The Senegal project was the latest in a series <strong>of</strong><br />

technical assistance and evaluation efforts by two<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the school’s Department <strong>of</strong> Community<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Sciences, Drs. Deborah Glik and Michael<br />

Prelip, to enhance digital and innovative health<br />

communication in West Africa. Funded by the<br />

Open Society Initiative for West Africa, the project’s<br />

research component asked two overarching questions:<br />