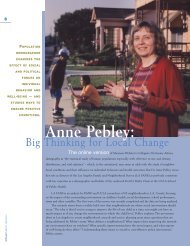

A BROADER VIEWOF HEALTH: - UCLA School of Public Health

A BROADER VIEWOF HEALTH: - UCLA School of Public Health

A BROADER VIEWOF HEALTH: - UCLA School of Public Health

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

the mouth. Untreated, tooth decay (cavities) – the<br />

most common chronic disease in children – can<br />

cause everything from pain and difficulty eating to<br />

lost school and work time. Serious oral disorders can<br />

undermine self-esteem, inhibiting children and adults<br />

from smiling. Gum disease has recently been linked<br />

in studies to increased risk for diabetes, heart disease<br />

and stroke.<br />

And while much attention has been paid to<br />

the problem <strong>of</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> health insurance, the fact<br />

that even more are without dental coverage is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

overlooked. Although public insurance programs<br />

such as Medicaid have increased coverage for children,<br />

dental benefits tend to be vulnerable to cuts in<br />

tough economic times. By the same token, for many<br />

low-income families struggling financially and, in<br />

some cases, lacking education about the importance<br />

<strong>of</strong> regular dental visits, dental care may be viewed<br />

as optional.<br />

“Oral health issues fit so closely with public<br />

health’s mission,” observes Andersen, “and through<br />

efforts aimed at prevention, education and addressing<br />

access issues, we have the potential to get more in<br />

return from our investment than from many other<br />

investments.”<br />

Dental public health issues haven’t been ignored<br />

at <strong>UCLA</strong>, where faculty in the <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong> and <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> Dentistry have worked – <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

together – to address some <strong>of</strong> the major concerns.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the key efforts began in 2001 when The<br />

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation provided funding<br />

for a national demonstration program aiming to<br />

reduce dental-care access disparities. Fifteen dental<br />

schools were selected to participate in the Dental<br />

Pipeline Program, which would receive additional<br />

funding from The California Endowment. The<br />

program’s national evaluation team was based in the<br />

<strong>UCLA</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>, with Andersen as<br />

the principal investigator and Dr. Pamela Davidson,<br />

associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health services at the school,<br />

as co-principal investigator. (The original project<br />

ended in 2007, but a follow-up study to measure its<br />

sustainability is ongoing.)<br />

The pipeline program was established in an<br />

effort to increase access to dental care in low-income<br />

and minority communities by recruiting more students<br />

from underrepresented minority groups to<br />

dental schools, improving dental school curricula to<br />

better prepare students to provide culturally competent<br />

care, and providing more clinical practice experiences<br />

for students in underserved communities.<br />

“If you look at the ethnicity <strong>of</strong> dentists compared to<br />

the distribution <strong>of</strong> the population, there are greater<br />

differences than in medicine,” Andersen notes. That<br />

has contributed in part to the shortage <strong>of</strong> oral health<br />

providers in minority communities, he says.<br />

Dental schools have faced significant challenges<br />

in their efforts to recruit minority students into<br />

dental careers, Andersen notes. For one, the shortage<br />

<strong>of</strong> providers in minority communities means there<br />

are few family members or friends serving as role<br />

models and mentors. Nonetheless, through steppedup<br />

efforts, including the establishment <strong>of</strong> pre-dental<br />

programs to assist students in meeting prerequisites,<br />

the pipeline program schools increased applications<br />

from underrepresented minority students by 77<br />

percent from 2003 to 2007, while enrollment <strong>of</strong><br />

underrepresented minority students increased by<br />

27 percent.<br />

Beyond the effort to increase the number <strong>of</strong><br />

minority dental providers, the pipeline program<br />

sought to revamp education and training experiences<br />

that would make all students more likely to consider<br />

careers in public health and service to underserved<br />

communities. While curricula were revised and the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> days senior dental students practiced<br />

in underserved communities increased, it’s unclear<br />

whether there was a corresponding increase in graduates<br />

going on to practice in these communities.<br />

Unfortunately, Andersen notes, dental students tend<br />

to enter practice with huge debts; thus, many who<br />

want to go into public service positions are deterred<br />

by the lower salaries and instead feel compelled to<br />

opt for private practice.<br />

The problem <strong>of</strong> disparities in utilization <strong>of</strong> dental<br />

services – particularly among children – is underscored<br />

by a recent study conducted by Dr. Nadereh<br />

Pourat, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health services and director <strong>of</strong><br />

research for the Center for <strong>Health</strong> Policy Research,<br />

which is based in the school. Using data from the<br />

2005 California <strong>Health</strong> Interview Survey, Pourat<br />

found that nearly 25 percent <strong>of</strong> California children<br />

ages 11 and under had never seen a dentist, and<br />

that among those who had, there were significant<br />

differences by race, ethnicity and type <strong>of</strong> insurance<br />

in the amount <strong>of</strong> time between dental care visits<br />

(see page 24).<br />

Having any kind <strong>of</strong> insurance significantly<br />

increased the odds that a child would see a dentist<br />

on a regular basis, but the type <strong>of</strong> coverage mattered:<br />

54 percent <strong>of</strong> privately insured children had seen<br />

a dentist within the previous six months, vs. 27<br />

percent <strong>of</strong> publicly insured children (Medicaid or<br />

the Children’s <strong>Health</strong> Insurance Program) and 12<br />

“<strong>Public</strong> programs<br />

are designed to<br />

improve access<br />

to care for<br />

underserved<br />

populations,<br />

and our study<br />

shows that they<br />

are successful<br />

in doing so.<br />

However,<br />

they don’t close<br />

the gap.”<br />

—Dr. Nadereh Pourat<br />

5<br />

feature <strong>UCLA</strong>PUBLIC <strong>HEALTH</strong>