BRIEF OF APPELLEE - The Indiana Law Blog

BRIEF OF APPELLEE - The Indiana Law Blog

BRIEF OF APPELLEE - The Indiana Law Blog

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TN TIlE<br />

COURToFAPPEALS<strong>OF</strong>ll{DLANA<br />

CAUSE No. 87A01- l 102-CR-25<br />

DAVID R. CAMM 1<br />

Appel/anI (Dejendcinf below),<br />

v.<br />

STATE <strong>OF</strong> lNDIANA,<br />

Appellee (Plaintiff below).<br />

Interlocutory Appeal from the Superior<br />

Court of Wanick County: Court II<br />

Cause No. 87D02 - 0506~MR- 054<br />

Hon. Jon A. Da11t Special Judge.<br />

<strong>BRIEF</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>APPELLEE</strong><br />

GREGORYF. ZOELLER<br />

All mey General of <strong>Indiana</strong><br />

Atty. No. J 58-98<br />

Joby D. lerrells<br />

Deputy Attorney General<br />

Alty. No. 24248-53<br />

Office ofAttomey Genera]<br />

<strong>Indiana</strong> Government Center<br />

South, Fifth Floor<br />

302 West Wasbington Street<br />

<strong>Indiana</strong>polis, TN 46204~2770<br />

Telephone: (3 17) 232-6232<br />

Attorneys for Appellee

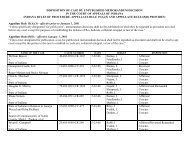

TABLE <strong>OF</strong> CONTENTS<br />

Table of Authorities .......... ......................... ..................................... ..................... .................... ii<br />

Statement of the Issue .................................................................. ........................................ .. .. 1<br />

Statement of the Case ....... ........................................................................................................ 1<br />

Statement of the Facts ............................................................................................................. 3<br />

Summary of the Argumt:nt. ...................................................................................................... 8<br />

Argument:<br />

THE COURT PROPERLY DENIED DEFENDANT'S PETITION FOR SPECIAL<br />

PROSECUTOR BECAUSE HE FAILED TO PROVE AN ACTUAL CONFLICT<br />

BY CLEAR AND CONVINCING EVIDENCE ..................................................... 10<br />

Standard of Re 1 1iew ...... ....................................................................... 10<br />

A. This Court must decline Defendant's invitation to address attorney<br />

disciplinary matters outside the Court's jurisdiction ................................ 10<br />

B. Defendant failed to prove an actual conflict by clear and convincing<br />

evidence .................................................................................. , ........ ..... .... J 2<br />

1. <strong>The</strong> trial court reached the right result, even if for the wrong<br />

reason ....................................................................... ..... ........ ....... 13<br />

2. <strong>The</strong>re is no actual conflict.. .......................................................... 15<br />

3. Removal is not necessary to avoid an actual conflict when<br />

sequestered voir dire and jury questionnaires will suffice .......... 29<br />

Conclusion<br />

.................... ....... ................... ....... ..... ........................................................ ..... 33<br />

Word Count Certificate .... ................................................. , ....... ................. .. ......... ................. 34<br />

Certificate of Service ............................................................................................................. 34

Table of Authorities<br />

CASES<br />

Banton v. State, 475 N.E.2d 1160 (Ind. Ct. App. 1985) ................................................................ 29<br />

Beets v. Collins, 65 F.3d 1258 (5th Cir. 1995) .............................................................................. 14<br />

Bennett v. NSR, Inc., 553 N.E.2d 881 (Ind. Ct. App. 1990) .......................................................... 11<br />

Camm v. State, 812 N.E.2d 1127 (Ind. Ct. App. 2004) ........................................................ passim<br />

Camm v. State, 908 N.E.2d 215 (Ind. 2009) ......................................................................... passim<br />

Carter v. Knox County Office of Family and Children, 761 N.E.2d 431 (Ind. Ct. App.<br />

2001) ................................................................................................................. ..... .................. 11<br />

Conner v. State, 580 N.E.2d 214 (Ind. 1991) ................................................................................ 30<br />

Cunningham v. State, 835 N.E.I075 (Ind. Ct. App. 2005) ............................................................ 11<br />

Cuyler v. Sullivan, 446 U.S. 335 (1980) (App. 250) ..................................................................... 14<br />

Fitzpatrick v. Kenneth J Allen and Associates, P.e., 913 N.E.2d 255 (Ind. Ct. App. 2009) ........ 11<br />

Garran v. State, 470 N.E.2d 719 (Ind. 1984) ................................................................................ 10<br />

Haraguchi v. Superior Court, 182 P.3d 579 (Cal. 2008) ....................................................... passim<br />

Hollywood v. Superior Court, 182 P .3d 590 (Cal. 2008) ........................................................ 26, 27<br />

In re McKinney, 948 N.E.2d 1154 (Ind. 2011) .... .................................................................... 28, 29<br />

Johnson v. State, 675 N.E.2d 678 (Ind. 1996) ................................................................... 16, 29,32<br />

Jorgensen v. State, 567 N.E.2d 113 (Ind. Ct. App. 1991) ............................................................. 13<br />

Kindred v. State, 521 N .E.2d 320 (Ind. 1988) ............................................................................... 13<br />

Kubsch v. State, 866 N.E.2d 726 (Ind. 1996) ..................................................... .. ................. passim<br />

Lamotte v. State, 495 N.E.2d 729 (Ind. 1986) ............................................................................... 16<br />

Liggett v. Young, 877 N .E.2d 178 (Ind. 2007) .................. ............................................................. 11<br />

Little v. State, 819 N.E.2d 496 (Ind. Ct. App. 2004) ..................................................................... 11<br />

11

Matter of Curtis, 656 N.E.2d 258 (Ind. 1995) ............................ ....................... .. .. ........................28<br />

Matter of Ryan, 824 N .E.2d 687 (Ind. 2005) ..................................... .......... .......... ........................28<br />

McFarlan v. Fowler Bank City Trust Co., 214 Ind. 10, 12 N.E.2d 752 (1938)...... .......... .. .. ......... 10<br />

Pelley v. State, 901 N.E.2d 494 (Ind. 2009) ................................ ......................... ................... 15, 21<br />

Penguin Books USA, Inc. v. Walsh, 756 F. Supp. 770 (S.D.N.Y. 1991) ......................... ..............22<br />

People v. Eubanks, 927 P.2d 310 (Cal. 2008) ...............................................................................16<br />

People v. Sims, 612 N.E.2d 1011 (Ill. Ct. App. 1993) ... .. .. .. ... ............ ... .. ......... .... ......... .. ...... passim<br />

Press Enterprise Co. v. Superior Court (I), 464 U.S. 501 (1984) .............................. ........... ...... .. 31<br />

Roeder v. State, 696 N.E.2d 62 (Ind. Ct. App. 1998) ..................... .......... .... ... .... ..... ..... ................18<br />

Sears v. State, 457 N.E.2d 192 (Ind. 1983) ...................................... ...... .... .... .... .. .. .......... ..............10<br />

Shaw v. Garrison, 467 F.2d 113 (5th Cir. 1972) .................. ..................... ...... ........................ 17, 18<br />

State ex reI. Long v. Warrick Circuit Court, 591 N.E.2d 559 (Ind. 1992) .. .................. .......... 13, 29<br />

Stale ex ReI. Steers v. Holovachka, 236 Ind. 565, 142 N.E.2d 593 (1957) .............. ..... .. .. ...... ...... 10<br />

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984) ........ ..... .. ....... ...................................... ........ .. ......14<br />

Stroble v. California, 343 U.S. 181 (1952) ....................................... .. .. ............... ..... ..... .... .. ..,.... ... 31<br />

Tippecanoe County Court, 432 N.E.2d 1377 (Ind. 1982) ............ ............... ......................... .. .. ...... 28<br />

United States v. Blanton, 719 F.2d 815 (6th Cir. 1983) ........... ......... ... .... ... ........ ..... ........... ........ ... 31<br />

United States v. Booker, 641 F.2d 218 (5th Cir. 1981) ....................... ........... ................. .........31, 32<br />

111

RULES<br />

Ind. Appellate Rule 4(B)(1 )(b) .............. ............... ... ...................................... ................................ 10<br />

Ind. Appellate Rule 46(A)(6) ...................... ........................... ...... ... ................................................ .3<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Rule 1.7 ................................................................. ................................ 7<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Rule 1.8(d) ......... .................................................................. 7, 20, 21, 25<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Rule 3.3(a)(1) ............ ........................................................................ 3, 7<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Rule 3.6 ................................................................................................. 7<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Rule 3.8 .... ............................................................................................. 7<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Rule 8.4(c) ........... ..... .... ....................... ..... ........ ................................ ..... 7<br />

STATUTES<br />

Ind. Code § 33-39-1-6(b)(2) .......................................................................................................... 13<br />

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS<br />

Ind. Const., Art. 7, Sec. 4 ........................... .... .. .............................................................................. 10<br />

OTHER AUTHORITIES<br />

48 Hours, One Deadly Night (http://www.cbsnews.com/storiesI2006/12/07/48hours/main<br />

2238837.shtml) ........................................................................................................................ 25<br />

ABA Standards for Criminal Justice: Fair Trial and Free Press (3d Ed. 1992) ............................. 31<br />

ABA Standards for Criminal Justice: Prosecution Function and Defense Function (3rd<br />

Ed. 1993) ............................................................................................................................ .. .... 20<br />

American <strong>Law</strong> Institute, Restatement (Third) of the <strong>Law</strong> Governing <strong>Law</strong>yers § 121 cmt.<br />

B) .............................................................................................................................................. 15<br />

IV

Mike McCarty, Choking in Fear (Arner Book Pub 2004) ............................................................ .25<br />

Internet Movie Database, JFK (http://www.imdb.com/title/ttOl 0213 8f) ...................................... 18<br />

Jeffrey Toobin, Opening Arguments: A Young <strong>Law</strong>yer's First Case (Viking 1991) ..... ............ ... 22<br />

John Dean, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Indiana</strong> Torture Slaying: Sylvia Likens' Ordeal & Death (BorfBooks<br />

1999) ................. ... ..... ................ ................................ ............... ....... .................. ... .................... 25<br />

John Gibeaut, Defend and Tell: <strong>Law</strong>yers who Cash in on Medial Dealsfor <strong>The</strong>ir Cleints'<br />

Stories may Wish <strong>The</strong>y'd Kept their Mouths Shut, 82-DEC AB.A 1.64 (1996) ................... 20<br />

John Glatt, One Deadly Night (St. Martin's Press 2005) ...... .. ............................. ..................... ..... 25<br />

John P. MacKenzie, "Peddling Iran-Contra Secrets," New York Times Editorial<br />

(February 8, 1991) ........... .. ... ....... ... .. ... ...... .... .......................................................................... 22<br />

Kathleen M. Ridolfi and Maurice Possley, Preventable Error: A Report on Prosecutorial<br />

Misconduct in California 1997-2009 (Veritas Initiative) (Oct. 2010) ......... ........................... .15<br />

Marjorie P. Slaughter, <strong>Law</strong>yers and the Media: <strong>The</strong> Right to Speak Versus the Duty to<br />

Remain Silent, 11 Geo. 1. Legal Ethics 89 (1997) ...... .. ............................................................ 20<br />

Mark McDonald, Literary-Rights Fee Agreements in California: Letting the Rabbit<br />

Guard the Carrot Patch of Sixth Amendment Protection and Attorney Ethics?, 24<br />

Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 365 (1991) .................................................................................................. 21<br />

Morley Swingle, Scoundrels (0 the Hoosegow: Perry Mason Moments and Entertaining<br />

Cases from the Files of a Prosecuting Attorney (University of Missouri Press 2007) ....... ... .. 22<br />

New York State Bar Association Ethics Op. 606 (1990) ............................... ................................ 21<br />

Rachel Luna, <strong>The</strong> Ethics of Kiss-and-Tell Prosecution: Prosecutors and Post-Trial<br />

Publications, 26 Am. J. Crim. L. 165 (1998) ................ .......................................................... 20<br />

Ria A Tabacco, Defensible Ethics: A Proposal to Revise the ABA Model Rules for<br />

Criminal Defense <strong>Law</strong>yer-Authors, 83 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 568 (2008) ........................................ 20<br />

Rita M. Glavin, Prosecutors who Disclose Proescutorial Information for Literary or<br />

Media Pwposes: What About the Duty of Confidentiality?, 63 Fordham L. Rev. 1809<br />

(1995) ........... ........ ........................ .............. ... .. ................................. .. ... ................................. .. 21<br />

Steve Miller, Girl Wanted: <strong>The</strong> Chase for Sarah Pender (Berkley 2011) .................. ................. .25<br />

Thomas Henry Jones, Fear no Evil (St. Martin's Press 2002) ...................................................... 25<br />

Tom Wolfe, Pornoviolence in Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine and other<br />

stories, sketches and essays (Farrar 1976) ............................................................................... 22<br />

v

Truman Capole, In Cold Blood (Signet 1965) .... ............................................................... ............ 22<br />

Vincent Bugliosi, And the Sea WiLl Tell: Murder on a Desert/sland (md Justice (Norton<br />

199 1) .......................... ................... .. ......................... .................................................. ........ ..... . 22<br />

Vincent Bugliosi, He/fer Ske/(er: <strong>The</strong> True Story 0/ the Alanson Murders (Bantam 1975) .......... 22<br />

Wensley Clark, Deadly Seducliol1 (SI. Martin's Press 1996) .................................................. ...... 25<br />

WLKY News, Camm To Be T;'jed Third Time In Family 's Slaying (http://www.wlky.com<br />

Inewsl2 1797043/dctai l.html) ................................................................................................... 17<br />

VI

IN THE<br />

COURT <strong>OF</strong> APPEALS <strong>OF</strong> INDIANA<br />

CAUSE No. 87A01-1102-CR-25<br />

DAVID R. CAMM,<br />

Appellant (Defendant below),<br />

v.<br />

STATE <strong>OF</strong> INDIANA,<br />

Appellee (Plaintiff below).<br />

Interlocutory Appeal from the Superior<br />

Court of Warrick County, Court II<br />

Cause No. 87D02-0506-MR-054<br />

Hon. Jon A. Dartt, Special Judge.<br />

<strong>BRIEF</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>APPELLEE</strong><br />

STATEMENT <strong>OF</strong> THE ISSUE<br />

Whether the trial court properly denied Defendant's petition for special prosecutor when<br />

Defendant failed to present clear and convincing evidence of an actual conflict of interest.<br />

STATEMENT <strong>OF</strong> THE CASE<br />

Nature of the Case<br />

David R. Camm ("Defendant") brings this interlocutory appeal from the trial court's<br />

denial of his petition for a special prosecutor (App. 282-83).<br />

Course of the Proceedings<br />

On October 1, 2000, the State charged Defendant with murdering his wife, Kimberly, and<br />

his two children, Bradley and Jill.! Camm v. State, 812 N.E.2d 1127, 1130 (Ind. Ct. App. 2004)<br />

(hereinafter "Camm r). Over the next decade, two juries - twenty-four people in all-<br />

I Prosecutor Stan Faith filed the charges in and prosecuted Camrn 1. Keith Henderson filed the<br />

charges in and prosecuted Camm 11.

impaneled from two different counties found Defendant guilty of the charges. See Id. at 1130;<br />

Camm v. State, 908 N.E.2d 215,220,238 (Ind. 2009) (4-1 decision) (hereinafter "Camm IF').<br />

On June 26, 2009, our Supreme Court reversed in Camm II, but addressed issues likely to arise<br />

on retrial in light of sufficient evidence to support Defendant's convictions. Id. at 220-21. On<br />

July 27, 2009, the State filed a petition for rehearing (Docket, Cause No. 87S00-0612-CR-499).<br />

On November 30, 2009, a divided court denied the State's petition for rehearing, three votes to<br />

two, without further opinion CAppo 39).<br />

On December 1,2009, Defendant filed a petition for a special prosecutor in the trial court<br />

(App.30-38). On December 14, 2009, the State filed its response to Defendant's petition CAppo<br />

44-45). Defendant filed a reply on December 18,2009, and requested a hearing (App. 51-55).<br />

On July 14, 2010, our Supreme Court removed Judge Aylsworth from the case and appointed<br />

Judge Dartt CAppo 100-01).<br />

On September 13,2010, Defendant moved to continue the hearing on his petition, to<br />

which the State objected (App. 152-56). <strong>The</strong> court conducted a hearing on November 24,2010<br />

(Tr. 1; App. 10). Defendant filed a memorandum in support of his petition on December 6, 2010<br />

(App. 10, 199-220). <strong>The</strong> State filed its memorandum opposing the petition on December 8,<br />

2010 (App. 221-32). On January 7, 2011, the court denied Defendant's petition for special<br />

prosecutor (App. 248-52).<br />

On January 20, 2011, Defendant filed a motion to certify the court's order for<br />

interlocutory appeal, which the court granted on the same day (App. 256-58). On February 3,<br />

2011, Defendant requested this Court to accept jurisdiction. CAppo 261-77; Docket). On<br />

February 16, 2011, the State submitted its response, indicating the State had no objection to this<br />

2

Court exercising jurisdiction over the case (App. 279; Docket). On March 11, 2011, this Court<br />

accepted jurisdiction over the interlocutory appeal (App. 281).<br />

On March 18, 2011, Defendant filed his notice of appeal (App. 12, 282-83). On April<br />

13, 2011, the clerk filed a notice of completion of clerk's record indicating the transcript was not<br />

yet completed (App. 285; Docket). On June 16,2011, the transcript was completed (App. 288;<br />

Docket). On July 18, 2011, Defendant filed his Brief of Appellant and Appendix, by personal<br />

service (Docket).<br />

STATEMENT <strong>OF</strong> THE FACTS 2<br />

Frank Weimann is a literary agent 3 for Literary Agency East, Ltd. (a/k/a "Literary Group<br />

International" and "LOI") (Exh. O. 5, 14, H.A). Weimann began representing Keith Henderson,<br />

the elected prosecutor in the current case, on March 10, 2006 (Exh. G 8, 11, Exh. H.A). <strong>The</strong><br />

initial duration of Weimann's agreement with Henderson was for one year, renewing<br />

automatically unless terminated by the parties in writing (Exh. H.A 1). Weimann initially<br />

contacted writer Steve Dougherty to co-author a book with Henderson regarding the Camm<br />

murders (Exh. 024). Dougherty and Henderson drafted a book proposal and submitted it to<br />

Weimann (Exh. F.A). Dougherty, however, did not believe the book deal was good enough for<br />

him and eventually withdrew from the project (Exh. 025). After Dougherty withdrew,<br />

2 Defendant's Statement of the Facts contains argumentative claims without citation to the<br />

record, e.g.: (1) "Thus, the amount of money Henderson was to make is dependent on the<br />

number of books he sold." Br. of Appellant at 4. <strong>The</strong> publisher actually expected Henderson's<br />

book to break even and noted that royalties paid to the authors often "fall short" of covering the<br />

advance (Exh. F 34-35); and (2) "After hearing nothing back from Henderson's agent, Penguin<br />

began tennination paperwork." Br. of Appellant at 5. <strong>The</strong> record indicates that Penguin agreed<br />

with Henderson's suggestion that the best solution was to void the contract and for Henderson to<br />

repay the advance (Exh. F.I). See <strong>Indiana</strong> Appellate Rule 46(A)(6) (requiring page references to<br />

the record and requiring facts to be stated in accordance with the standard of review). See also,<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Rule 3.3(a)(1) (requiring candor toward the tribunal).<br />

3 A literary agent is an intermediary between authors and publishers (Exh. G. 5).<br />

3

Weimann subsequently made other arrangements with another writier, Damon DiMarco, to coauthor<br />

the book (Exh. G 26).<br />

To promote a project, Weimann's practice was to contact publishers using a "pitch"<br />

letter, which sometimes included a book proposal (Exh. G 33). Weimann contacted Harper<br />

Collins on October 6, 2008, to determine if there was any interest to publish the book, but there<br />

was none (Exh. G 31; Exh. H.C). On November 24, 2008, Bantam Dell Publishing Group also<br />

passed on the book (Exh. G 33; Exh. H.D). On June 3, 2009, Weimann negotiated a publishing<br />

agreement between HenderS0I! and the Berkley Penguin Group, a publisher, regarding the Camm<br />

murders tentatively titled "Sacred Trust: Deadly Betrayal" (Exh. G 15; Exh. H.B).4 <strong>The</strong> parties<br />

did not specifically anticipate a reversal of Defendant's convictions; however, the contract<br />

included a cancellation clause (Exh. E 29). <strong>The</strong> non-delivery of the manuscript would have<br />

triggered the cancellation clause, terminating the publishing contract (Exh. E 29). <strong>The</strong> typical<br />

advance for a true crime book is approximately $10,000.00, which is the amount Penguin<br />

eventually offered (Exh. E 21, 49).<br />

Penguin previously prepared a pre-acquisition profit and loss statement with Henderson<br />

and Dougherty as the authors for an estimated publication date during the summer of201 0 (Exh.<br />

E 42, F.D). <strong>The</strong> statement shows that Penguin predicted gross sales of approximately<br />

$95,880.00 and net sales of $47,940.00 (Exh. F.D). Penguin estimated the company would make<br />

a gross profit of $30,782 (Exh. F .D). When a book is successful, the author can earn royalties;<br />

however, based on past experience, Penguin expected Henderson's book to break even (Exh. E<br />

34-35). In Penguin's publishing experience, subsequent royalties to authors often "fall short" of<br />

4 Henderson and DiMarco also suggested two other titles for the book, including: "Murder in the<br />

Midwest: <strong>The</strong> Second and Final Trial of David Camm" and "Murder in the Midwest: <strong>The</strong> Final<br />

Trial of David Camm" (Exh. F.C).<br />

4

manuscript for a book from HF:!1derson and Henderson never shared with Weimann any<br />

information or evidence about the case that was not already part of the public record (Exh. G 76,<br />

84). In Weimann's opinion, if Defendant were convicted by a third jury, it "might help the<br />

book" (Exh. G 98). Or, if Defendant were found not guilty, "the big, bad prosecutor, innocent<br />

man, you know, accused of a terrible crime and ultimately wins - that's a big book too" (Exh. G<br />

99).<br />

Irrespective of the outcome of Defendant's third trial, Weimann stated that if Henderson<br />

wanted to write a book after the third trial, Henderson would have to start over, i.e., find an agent<br />

and a publisher (Exh. G 97-98). Henderson has no present contract to write a book regarding the<br />

Camm murders (Exhs. E 40,51, G 96-97). Penguin's representative also concurred that there is<br />

no "wink-and-a-nod" agreement with Henderson regarding a book about a third trial (Exh. E 52,<br />

54).<br />

At the hearing on the petition for special prosecutor, the parties agreed to the<br />

admissibility of Defendant's exhibits (Tr. 7-8). On December 2, 2009, Henderson issued a press<br />

release in response to Defendant's petition for special prosecutor (Exh. J). Henderson reiterated<br />

that there was no book deal related to the case and that once the case was reversed, the<br />

publishing agreement was terminated (Exh. J). Henderson did state, however, that he was "more<br />

convinced now than ever that when this matter is completed, the unedited version of events<br />

needs to be told" (Exh. J). On December 3, 2009, Henderson issued another press release<br />

indicating that he would re-try Defendant for killing his wife and children (Exh. K). <strong>The</strong><br />

December 3rd press release contained similar language regarding the book deal and termination<br />

of the agreement (Exh. K). Henderson also relayed that the Supreme Court had stated in its<br />

6

opinion that "there's ample evidence outside of the child molest evidence for the convictions"<br />

(Exh. K).<br />

At the hearing on Defendant's petition, Defendant presented one witness, Norman<br />

Lefstein, a law professor, who was paid $275.00 per hour for approximately twenty hours of<br />

work on the case (Tr. 75). Lefstein opined that the two press releases violated the Rules of<br />

Professional Conduct, specifically Rule 3.6 (trial publicity) and 3.8 (special responsibilities of a<br />

prosecutor) (Tr. 25). Lefstein also reviewed two pleadings filed on August 29,2007, which the<br />

State filed in response to Defendant's proposed statement of evidence regarding the record<br />

during the direct appeal (Exhs. B, C). Both Henderson and his Chief Deputy, Steve Owen,<br />

represented their recollection of the events about the record in response to Defendant's pleadings<br />

(Exhs. B, C). Lefstein opined that the responsive pleadings violated Rule 3.3(a)(l) (candor<br />

toward the tribunal) and 8.4(c) (misconduct, dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation) (Tr.<br />

25). Lefstein further opined that Henderson's previous book deal violated Rule 1.8( d) (conflict<br />

of interest, literary rights) and Rule 1. 7 (conflict of interest, current clients) (Tr. 46-47).<br />

After reviewing the depositions, pleadings, and exhibits, Lefstein ultimately concluded in<br />

his opinion that "it seems to me that the State of <strong>Indiana</strong> is entitled to a prosecutor in this case<br />

who is not unfettered by such a reality here ... who does not have the same past with this case<br />

that Mr. Henderson clearly does" (Tr. 70). Lefstein admitted that the book deal had been<br />

terminated in August of 2009, and that Henderson had no contract at that time (Tr. 78, 86).<br />

Lefstein conceded that Henderson was not violating Rule 1.8(d) at the time of the hearing (Tr.<br />

86). Lefstein further opined that the conflicts rule continued until it was "really clear" there was<br />

no potential for re-prosecution, even through post-conviction (Tr. 95). In Lefstein's opinion, a<br />

book deal, even if done for free, creates a conflict of interest dividing the loyalties of the<br />

7

prosecutor between his own self-interest and his duty to be a minister of justice (Tr. 96-98).<br />

Lefstien also stated that a prosecutor may even commit unethical acts during the prosecution of a<br />

given case which would not necessarily lead to disqualification or justify removal of the<br />

prosecutor from the case (Tr. 109).<br />

After taking the matter under advisement, the Court issued an order denying Defendant's<br />

petition for special prosecutor (App. 248-52). <strong>The</strong> court found that there was no longer an<br />

agreement to publish a book arising from the instant case but that Henderson might pursue a<br />

book deal at some time in the future (App. 249). <strong>The</strong> court noted: "It is not for this Court to<br />

determine what ethical violations occurred, if any, and then what sanction should be imposed on<br />

the prosecutor for those violations" (App. 251). <strong>The</strong> court further reasoned:<br />

<strong>The</strong> defense has presented "some evidence" of a "potential conflict" but there has<br />

been no showing that the prosecutor's past book agreement has affected his<br />

prosecution of the case for the people of the State of<strong>Indiana</strong>. For example, even<br />

though the case has now been reversed twice and the prosecutor has chosen to<br />

proceed to trial fDr a third time, that decision has not been shown to be against the<br />

State's interests by "clear and convincing" evidence as even our own Supreme<br />

Court held that there is sufficient evidence for a jury to find the defendant guilty<br />

at trial<br />

(App. 251). <strong>The</strong> court acknowledged that it heard evidence of how the book agreement "could"<br />

impact Henderson's loyalties and decisions but heard "no actual evidence that it 'has' affected<br />

those loyalties or decisions" (App. 251). Additional facts from the record will be incorporated as<br />

necessary and cited accordingly.<br />

SUMMARY <strong>OF</strong> THE ARGUMENT<br />

Defendant failed to present clear and convincing evidence of an actual conflict<br />

necessitating removal of the prosecutor. First, Defendant cannot use the Rules of Professional<br />

Conduct as a procedural weapon to remove the prosecutor from the instant case. <strong>The</strong> Rules do<br />

not give Defendant standing or create a private right of action to remove an attorney from<br />

8

litigation. Defendant attempts to bootstrap multiple claims of unethical conduct to require<br />

Henderson to be removed as prosecutor, which in any event is an extreme remedy, reserved only<br />

for cases involving an actual conflict which necessitates removal, shown by clear and convincing<br />

evidence. Defendant has failed to carry his heavy burden.<br />

At most, the evidence shows that the prosecutor entered into a book deal just before our<br />

Supreme Court reversed Defendant's three murder convictions for the second time. Just over a<br />

month later, the parties terminated the book deal, as well as the literary agent's contract. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

no current book deal and the prosecutor would have to start the process over to obtain such a<br />

deal. <strong>The</strong> trial court concluded that there is no actual conflict. Defendant cannot demonstrate<br />

any harm in the discretionary decisions of the prosecutor, including: <strong>The</strong> charging decision, the<br />

plea bargaining process, or a sentencing recommendation.<br />

Any remaining concerns of prosecutorial misconduct, such as those which might arise<br />

during the normal course of a trial, exist regardless who prosecutes the case. Defendant's right<br />

to a fair trial would adequately protect him against any actual misconduct during the course of a<br />

trial.<br />

Moreover, the prosecutor has nothing more than a mere hope of a book deal at some point<br />

in the future, which would exist regardless who might prosecute the case.<br />

Even if there was some evidence of a potential conflict, removal is unwarranted. <strong>The</strong><br />

trial court can simply utilize jury questionnaires and/or conduct a sequestered voir dire to<br />

determine whether any prospective jurors are aware of a book deal.<br />

9

ARGUMENT<br />

THE COURT PROPERLY DENIED DEFENDANT'S PETITION FOR SPECIAL PROSECUTOR BECAUSE<br />

HE FAILED TO PROVE AN ACTUAL CONFLICT BY CLEAR AND CONVINCING EVIDENCE.<br />

Standard of Review<br />

This Court will review a trial court's denial of a motion for special prosecutor for an<br />

abuse of discretion. State ex Rei. Steers v. Holovachka, 236 Ind. 565, 142 N.E.2d 593, 597<br />

(1957). <strong>The</strong> trial court has discretion whether to grant or deny the motion. Kubsch v. State, 866<br />

N.E.2d 726, 734 (Ind. 1996) (stating the trial court "rightly denied" motion for special<br />

prosecutor); Garran v. State, 470 N.E.2d 719, 723 (Ind. 1984) (finding no error in the trial<br />

court's ruling granting the special prosecutor motion as to the habitual offender allegation, but<br />

denying the motion as to the State's case-in-chief); Sears v. State, 457 N.E.2d 192, 195 (Ind.<br />

1983) (stating the trial court acted properly in appointing a special prosecutor). An abuse of<br />

discretion will be found when it is clearly against the logic of the court, or the reasonable<br />

inferences drawn therefrom. Holovachka, 142 N.E.2d at 597; see also McFarlan v. Fowler Bank<br />

City Trust Co., 214 Ind. 10, 12 N.E.2d 752,754 (1938).<br />

A. This Court must decline Defendant's invitation to address attorney disciplinary<br />

matters outside the Cuurt's jurisdiction.<br />

Throughout his brief, Defendant consistently charges Henderson with making allegedly<br />

unethical statements to the press, defrauding the court by making allegedly untrue statements,<br />

and entering into a book deal that incurably divided Henderson's loyalties between his own<br />

allegedly selfish interests and his duty as a minister of justice. <strong>The</strong> trial court, however, properly<br />

focused on the legal issue, i.e., whether Henderson had an actual conflict, instead of Defendant's<br />

drumbeat allegations of alleged attorney misconduct. See Order (App. 251).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Indiana</strong> Constitution grants exclusive jurisdiction over attorney disciplinary matters<br />

to the <strong>Indiana</strong> Supreme Court. Ind. Const., Art. 7, Sec. 4; see also <strong>Indiana</strong> Appellate Rule<br />

10

4(B)(1)(b); Cunningham v. State, 835 N.E.1075, 1079 n.6 (Ind. Ct. App. 2005). Imposing<br />

attorney discipline and protecting a defendant's constitutional rights are separate matters. Little<br />

v. State, 819 N.E.2d 496, 503 n.3 (Ind. Ct. App. 2004). This Court has repeatedly declined to<br />

step outside its jurisdiction and act as a disciplinary body to determine whether an attorney's<br />

actions are unethical. Bennett v. NSR, Inc., 553 N.E.2d 881,884 (Ind. Ct. App. 1990) (refusing<br />

to address whether an attorney's conduct was unethical); cf Carter v. Knox County Office of<br />

Family and Children, 761 N.E.2d 431, 434-35 (Ind. Ct. App. 2001) (concluding that a trial<br />

judge's violation of the Code of Judicial Conduct was not a proper consideration for the court).<br />

It is important to note that in Camm ll, our Supreme Court never stated that Henderson or the<br />

State committed any prosecutorial misconduct. 5 Simply repeating ad hominem that Henderson<br />

acted unethically and committed misconduct is insufficient to make it so.<br />

Moreover, <strong>Indiana</strong>'s Rules of Professional Conduct do not create standing or a private<br />

right of action permitting Defendant to obtain any relief for alleged ethical misconduct. <strong>The</strong><br />

Rules "have limited application outside of the attorney disciplinary process." Liggett v. Young,<br />

877 N.E.2d 178, 182 (Ind. 2007); Fitzpatrick v. Kenneth J Allen and Associates, p.e, 913<br />

N.E.2d 255, 267 (Ind. Ct. App. 2009). <strong>The</strong> preamble to the Rules provides in relevant part:<br />

Violation of a Rule should not itself give rise to a cause of action against a<br />

lawyer, nor should it create any presumption in such a case that a legal duty has<br />

been breached. In addition, violation of a Rule does not necessarily warrant any<br />

other nondisciplinary remedy, such as disqualification of a lawyer in pending<br />

litigation .. <strong>The</strong> Rules are designed to provide guidance to lawyers and to provide<br />

a structure for regulating conduct through disciplinary agencies. <strong>The</strong>y are not<br />

designed to be a basis for civil liability, but the Rules may be used as nonconclusive<br />

evidence that a lawyer has breached a duty owed to a client.<br />

Furthermore, the purpose of the Rules can be subverted when they are invoked by<br />

opposing parties as procedural weapons. <strong>The</strong> fact that a rule is a just basis for a<br />

lawyer's self-assessment, or for sanctioning a lawyer under the administration of a<br />

disciplinary authority, does not imply that an antagonist in a collateral proceeding<br />

5 Henderson did not prosecute Camm 1.<br />

11

or transaction has standing to seek enforcement of the Rule. Nevertheless, since<br />

the Rules do establish standards of conduct by lawyers, a lawyer's violation of a<br />

Rule may be evidence of breach of the applicable standard of conduct.<br />

Ind. Professional Conduct Preamble ~ 20 (emphasis supplied). Defendant's blatant attempt to<br />

bootstrap Henderson's alleged ethical misconduct as a procedural weapon to remove Henderson<br />

from the case is not pennitted under the Rules. Moreover, Henderson's client is the State of<br />

<strong>Indiana</strong>, not Defendant. Defendant cannot raise a claim on behalf of the citizens of the State of<br />

<strong>Indiana</strong>. Instead, Defendant can only claim, and must prove by clear and convincing evidence,<br />

that Henderson has a conflict of interest necessitating removal. Accordingly, this Court must<br />

reject Defendant's invitation to condemn Henderson for alleged misconduct and instead, address<br />

only whether trial the court acted within its discretion to deny Defendant's petition for special<br />

prosecutor.<br />

B. Defendant failed to prove an actual conflict by clear and convincing evidence.<br />

Defendant's proof that Henderson had a conflict of interest fell well short of his<br />

evidentiary burden. When a defendant requests a special prosecutor, the Legislature has<br />

established that the trial court:<br />

may appoint a special prosecutor if:<br />

(A)<br />

(B)<br />

a person files a verified petition requesting the appointment of a special<br />

prosecutor; and<br />

the court, after:<br />

(i)<br />

(ii)<br />

notice is given to the prosecuting attorney; and<br />

An evidentiary hearing is conducted at which the prosecuting<br />

attorney is given an opportunity to be heard;<br />

finds by clear and convincing evidence that the appointment is necessary to avoid<br />

an actual conflict of interest or there is probable cause to believe that the<br />

prosecutor has committed a crime[.]<br />

12

Ind. Code § 33-39-1-6(b)(2) (emphasis supplied). <strong>The</strong> import of the special prosecutor statute as<br />

a whole is significant and "incorporates a recognition of the grave nature of disqualification and<br />

the goal of comprehensively restraining disqualifications to situations of real need." State ex reI.<br />

Long v. Warrick Circuit Court, 591 N.E.2d 559,560 (Ind. 1992) (discussing prior version of the<br />

statute). "Ultimately, it is the defendant's burden to produce evidence of an actual conflict[.J"<br />

Kubsch, 866 N.E.2d at 734. A prosecutor's apparent prejudice against defendant does not satisfy<br />

the requirements for appointment of a special prosecutor. Kindred v. State, 521 N .E.2d 320, 327<br />

(Ind. 1988). A trial court is not bound to accept a defendant's self-serving contention that a<br />

special prosecutor is necessary. Jorgensen v. State, 567 N.E.2d 113,123 (Ind. Ct. App. 1991).<br />

<strong>The</strong> court properly denied Defendant's petition due to Defendant's failure to prove an actual<br />

conflict, let alone by clear and convincing evidence.<br />

1. <strong>The</strong> trial court reached the right result, even if for the wrong reason.<br />

<strong>The</strong> State agrees that the trial com1 seemingly applied an unpersuasive body of law to the<br />

facts in this case to assess whether there was an actual conflict. <strong>The</strong> court's reasoning was an<br />

exampl e of what logicians would call "weak induction." By its nature, any kind of induction,<br />

weak or strong, allows for the possibility that the conclusions are false, as opposed to deductive<br />

reasoning, wherein true premises necessitate true conclusions in any valid argument. <strong>The</strong> logic<br />

of the court's reasoning is as follows:<br />

Some defense attorneys who write books about cases do not have a conflict of<br />

interest;<br />

<strong>The</strong> prosecutor may have had an interest in writing a book about this case;<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, the prosecutor does not have a conflict of interest.<br />

See Order CAppo 250-51). This flawed logical reasoning can be characterized as either: (l)<br />

universalizing from a particular; (2) drawing a false analogy; or (3) arriving at a hasty<br />

13

generalization. <strong>The</strong> court assumes that the prosecutor in this case fits into the class of those<br />

defense attorneys who have written about cases without creating a conflict, and applies that<br />

assumption to all lawyers. <strong>The</strong> analogy between the two classes of attorneys, prosecutors and<br />

defense attorneys, is unpersuasive, essentially comparing apples to oranges. <strong>The</strong> flaw in the<br />

court's approach reaches a broad conclusion without a more detailed examination ofthe class of<br />

attorneys for whom no conflict exists. Thus, in anyone of three different ways, the court's<br />

reasoning assumes the form of a weak induction.<br />

<strong>The</strong> court's reasoning is based upon ineffective assistance of counsel claims. <strong>The</strong> trial<br />

court discussed the concept of "actual conflict" as used by the Supreme Court in Cuyler v.<br />

Sullivan, 446 U.S. 335 (1980) (App. 250). Cuyler was a multiple representation case where<br />

defense counsel represented TP-ultiple defendants. !d. at 337-38. <strong>The</strong> Cuyler majority concluded<br />

that the possibility of a conflict was insufficient to find ineffective assistance. Id. <strong>The</strong> trial court<br />

also examined Beets v. Collins, 65 F.3d 1258 (5th Cir. 1995) (applying Cuyler) (App. 250-51).<br />

<strong>The</strong> defendant in Beets transferred her media rights in the case to her defense attorney just after<br />

her trial commenced. Id. at 1261-62. <strong>The</strong> trial court became aware of the contract at the time of<br />

the appeal. Id. at 1262. <strong>The</strong> Fifth Circuit in Beets, however, declined to apply Cuyler outside of<br />

the multiple representation fact pattern, opting instead to apply Strickland v. Washington, 466<br />

U.S. 668 (1984). Beets, 65 F.3d at 1266, 1271-72. While Cuyler, Strickland, a~d Beets are<br />

instructive regarding a defense attorney's conduct, the cases do not address whether a prosecutor<br />

has an actual conflict necessitating removal. Though the court's conclusion in this case, i.e., that<br />

Henderson has no conflict, is true, the conclusion cannot be established by the court's premises.<br />

Instead of using ineffective assistance caselaw, the court should have focused on whether<br />

there was an actual conflict between Henderson and Defendant necessitating removal. <strong>The</strong> trial<br />

14

court cited Pelley v. State, 901 N.E.2d 494 (Ind. 2009), where our Supreme Court recently<br />

rejected a similarly vague claim as Defendant raises here that the appearance of impropriety was<br />

sufficient to necessitate rernev:!l of a prosecutor, without any showing as to the nature or<br />

substance of allegedly confidential communication between prosecutor and a defendant he<br />

formerly interviewed as a witness when the prosecutor was a defense attorney. Jd.506-07. Our<br />

Supreme Court adopted a conservative approach to address the special prosecutor statute, and<br />

reasoned that "avoiding conflicts of interest can impose significant costs on lawyers and clients.<br />

Prohibition of conflicts of interest should therefore be no broader than necessary." Jd. at 507<br />

(quoting Restatement (Third) of the <strong>Law</strong> Governing <strong>Law</strong>yers § 121 cmt. B) (internal quotations<br />

omitted). <strong>The</strong> Pelley court applied the law to the facts and succinctly concluded there was no<br />

conflict. Pelley, 901 N.E.2d at 507. While the trial court here reached the right result, a<br />

straightforward application of Pelley would have achieved the same result without drawing a<br />

false analogy between claims of ineffective assistance and petitions for special prosecutors.<br />

Defendant's claims here demonstrate no actual conflict which places his constitutional right to a<br />

fair trial in jeopardy. Accordingly, the trial court reached the right result, if for the wrong<br />

reason.<br />

2. <strong>The</strong>re is no actual conflict.<br />

Defendant's claim of an actual conflict is vague and without merit. At the outset, it is<br />

important to understand the range of misconduct or unethical behavior by prosecutors. <strong>The</strong><br />

Northern California Innocence Project recently issued a report which provides a useful<br />

taxonomy. See Kathleen M. Ridolfi and Maurice Possley, Preventable Error: A Report on<br />

Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 1997-2009 (Veritas Initiative) (Oct. 2010). Based on an<br />

extensive review of cases, the authors categorize and classify several types of misconduct,<br />

15

including: intimidating witnesses; presenting false evidence; discriminatory jury selection;<br />

violating the Fifth Amendment right to silence; failing to disclose exculpatory evidence;<br />

improper examination; and, improper argument. ld. at 25. This taxonomy helps put<br />

Henderson's alleged misconduct and unethical acts in the proper context, which is to assess<br />

,-.<br />

whether Defendant will receive a fair trial.<br />

Defendant makes a general ambiguous claim about the "countless decisions" Henderson<br />

will make as the prosecutor on the case. See Br. of Appellant 22. <strong>The</strong>re are three discretionary<br />

decisions of any import, easily answered, that Henderson must make regarding the instant case:<br />

(1) whether to the charge Defendant at all; (2) whether to offer Defendant a plea bargain; and (3)<br />

what sentence to recommend to the court, if Defendant is convicted for the third time of<br />

murdering his wife and children. People v. Eubanks, 927 P.2d 310 (Cal. 2008), a California<br />

Supreme Court case, provides some guidance. <strong>The</strong> Eubanks court focused on the prosecutor's<br />

discretionary powers, reasoning that prejudice is most likely to arise during the charging, plea<br />

bargaining, and the sentencing phases of a criminal case. ld. at 318; While our Supreme Court<br />

has not fully explored the issue, the Court has considered the impact of conflicts on the<br />

discretionary functions ofthe prosecutor. See, e.g., Kubsch, 866 N.E.2d at 733-34 (discussing<br />

the plea bargaining phase). None of those considerations here, however, has any merit.<br />

Charges against Defendant were inevitable, regardless who prosecuted the case. <strong>The</strong><br />

determination of whom to prosecute lies within the sole discretion of the prosecutor and the<br />

reviewing court "may not substitute its discretion for that of the prosecuting attorney." Johnson<br />

v. State, 675 N.E.2d 678,683 (Ind. 1996) (citing Lamotte v. State, 495 N.E.2d 729, 733 (Ind.<br />

1986)). Two independently elected prosecutors - both of whom represented the will of the<br />

people of Floyd County - chose to file charges against Defendant. Stan Faith, Henderson's<br />

16

predecessor in office, charged and prosecuted Defendant in Camm 1. Henderson charged and<br />

prosecuted Defendant in Camm II. Two juries - twenty-four people in all- impaneled from two<br />

different counties found Defendant guilty of murdering Kim, Brad, and Jill. See Camm 1,812<br />

N.E.2d at 1130; Camm 11,908 N.E.2d at 238. Both this Court and our Supreme Court held that<br />

there was sufficient evidence to re-try Defendant in each of the respective appeals. Camm 1,812<br />

N.E.2d at 1138-39; Camm 11,908 N.E.2d at 220-21. Defendant is not entitled to choose his own<br />

prosecutor as that right belongs to the voters of Floyd County.<br />

Any prosecutor would have charged Defendant after Camm II. Henderson served the<br />

public's interest when he made the inevitable conclusion to charge Defendant for the third time,<br />

based on the evidence which our Supreme Court found sufficient to support a retrial, and nearly<br />

affirmed in a split decision on rehearing. Though it may have been Henderson's decision<br />

whether to charge Defendant, it is the court's decision whether to find probable cause supporting<br />

the charging decision. Not even Defendant's uncle was surprised when Henderson announced<br />

that Defendant would be tried for the third time. See WLKY News, Camm To Be Tried Third<br />

Time In Family's Slaying (available at http://www.wlky.com/news/21797043/detail.html) (last<br />

visited on July 21, 2011). Defendant has suffered no harm because any prosecutor in the State of<br />

<strong>Indiana</strong> would have charged him with murder, and there is probable cause to support those<br />

charges and sufficient evidence to sustain convictions if obtained.<br />

Defendant's reliance on Shaw v. Garrison, 467 F.2d 113 (5th Cir. 1972), asserting that<br />

Henderson improperly charged Defendant, is sorely misplaced. See Br. of Appellant 22-23.<br />

Garrison, a prosecutor in New Orleans, prosecuted Shaw for allegedly plotting to assassinate<br />

President John F. Kennedy. Id. at 118-19. Garrison's case against Shaw was later popularized<br />

17

in Director Oliver Stone's conspiracy theory movie, JFK. 6 Shaw was acquitt~d of conspiring to<br />

assassinate President Kennedy. Shaw, 467 F.2d at 118. Even so, Garrison continued his pattern<br />

of "relentless harassment" of Shaw and attempted to prosecute him for perjury. Id. at 114.<br />

Garrison had written one book about his prosecution of Shaw and was under contract to write<br />

three additional books at the time of the perjury prosecution. Id. <strong>The</strong> Fifth Circuit affirmed the<br />

District Court's findings that Garrison brought the perjury prosecution in bad faith and for the<br />

purpose of harassing Shaw. !ei. at 122. Unlike Shaw, who was acquitted of conspiring to kill<br />

John F. Kennedy, Defendant has twice been convicted of murdering Kim, Brad, and Jill.<br />

Whereas Shaw involved a vindictive prosecution, the instant case does not. Moreover, unlike<br />

Garrison who had already written a book about the case and was under contract to write<br />

additional books, Henderson has no cook contract. Conspiracy theories are best left where they<br />

belong, Hollywood and the internet, not before this Court on appeal.<br />

Defendant can perhaps claim that Henderson's decision not to offer a plea bargain<br />

prejUdices him in some way. Defendant has maintained his innocence throughout this case. It is<br />

unlikely that Defendant is willing to accept responsibility for killing Kim, Brad, and Jill.<br />

Moreover, because a defendant has no constitutional right to engage in plea bargaining, the<br />

prosecutor has no duty to plea bargain. Roeder v. State, 696 N.E.2d 62, 64 (Ind. Ct. App. 1998).<br />

Accordingly, Henderson's discretionary decision whether to offer a plea presents no actual<br />

conflict of interest because Defendant has no constitutional right to engage in plea bargaining<br />

and is of no consequence in light of Defendant's claims of innocence. Cf Kubsch, 866 N.E.2d at<br />

733-34 (reasoning that a prosecutor's prior representation of a witness did not impair<br />

6 See Internet Movie Database, JFK (available at http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0102138/) (last<br />

visited August 10,2011).<br />

18

prosecutor's duty of impartiality to the accused during the plea bargaining process where the<br />

accused was unwilling to participate ~n the plea bargaining process).<br />

Henderson's possible recommendation at sentencing is also not at issue. In Camm I,<br />

Judge Striegel sentenced Defendant to 195 years. Camm I, 812 N.E.2d at 1130. In Camm 11,<br />

Judge Aylsworth sentenced Defendant to life without parole. Camm 11, 908 N.E.2d at 219.<br />

Defendant is in no worse a position as in the sentencing phase of Camm 11 where he received life<br />

without parole. Defendant's claim of a vindictive prosecution or that Henderson will make<br />

countless decisions falls flat when examining the mechanics of the three essential discretionary<br />

prosecutorial decisions, charging, plea bargaining, and sentencing.<br />

Defendant's constitutional rights are protected by the State and federal constitutions for<br />

any other claims of unethical conduct committed by any of the prosecutors during Defendant's<br />

third trial, including the types of misconduct categorized in the Veritas Initiative report. This<br />

Court will not remove Henderson, or any other prosecutor for that matter, upon the mere<br />

speculation that he or she might do something unethical during a future trial or upon the mere<br />

appearance of impropriety. Instead, the trial court may only remove a prosecutor upon a<br />

showing of an actual conflict by clear and convincing evidence. Kubsch, 866 N.E.2d at 731.<br />

Furthermore, no court has ever said that Henderson or any other prosecutor in this case has<br />

committed prosecutorial misconduct. <strong>The</strong> learned professor even conceded that not all<br />

prosecutorial misconduct warrants removal (Tr. 109). <strong>The</strong> only remaining colorable argument<br />

supporting Defendant's petition for a special prosecutor concerns Henderson's rescinded book<br />

deal with Penguin.<br />

Henderson has no book deal, and, therefore, no current conflict of interest. As a general<br />

rule, "[p]rior to the conclusion of representation of a client, a lawyer shall not make or negotiate<br />

19

an agreement giving the lawyer literary or media rights to a portrayal or account based in<br />

substantial part on information relating to the representation." Prof. Condo Rule 1.8( d). <strong>The</strong><br />

American Bar Association ("ABA") has published a treatise regarding prosecutorial standards<br />

which addresses literary or media agteements. See ABA Standards for Criminal Justice:<br />

Prosecution Function and Defense Function (3rd Ed. 1993). Standard 3-2.11 states:<br />

A prosecutor, prior to conclusion of all aspects of a matter, should not enter into<br />

any agreement or understanding by which the prosecutor acquires an interest in<br />

literary or media rights to a portrayal or account in substantial part on information<br />

relating to that matter.<br />

Id. at 45. <strong>The</strong> commentary to Standard 3-2.11 suggests the following:<br />

An agreement by which a prosecutor acquires literary or media rights concerning<br />

a pending criminal matter can create a conflict between the interests of the<br />

government in obtaining a just and fair outcome and the personal interests of the<br />

prosecutor in having a good (or outrageous) story to tell. Measures that should be<br />

taken in the interests of effective prosecution may detract from the publication<br />

value of a subsequent account of the prosecution. Hence, entering into such<br />

literary or media agreements prior to the conclusion of all aspects of a criminal<br />

matter should be scrupulously avoided.<br />

Id. at 45--46. Contrary to Professor Lefstein's paid testimony, Rule 1.8( d) differs from the ABA<br />

standard and does not create an absolute prohibition balU1ing prosecutor literary agreements,<br />

especially when read with Standard 3-2.11 and its accompanying commentary (Tr. 26).<br />

<strong>Law</strong>yers' media rights have also received substantial attention in legal periodicals. See,<br />

e.g., Ria A. Tabacco, Defensible Ethics: A Proposal to Revise the ABA Model Rules for<br />

Criminal Defense <strong>Law</strong>yer-Authors, 83 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 568 (2008); Rachel Luna, <strong>The</strong> Ethics of<br />

Kiss-and-Tell Prosecution: Prosecutors and Post-Trial Publications, 26 Am. J. Crim. L. 165<br />

(1998); Marjorie P. Slaughter, <strong>Law</strong>yers and the Media: <strong>The</strong> Right to Speak Versus the Duty to<br />

Remain Silent, 11 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 89 (1997); John Gibeaut, Defend and Tell: <strong>Law</strong>yers who<br />

Cash in on Medial Deals for <strong>The</strong>ir Cleints' Stories may Wish <strong>The</strong>y'd Kept their Mouths Shut, 82-<br />

20

DEC AB.A J. 64 (1996); Rita M. Glavin, Prosecutors who Disclose Proescutorial Information<br />

for Literary or Media Purposes: What About the Duty of Confidentiality?, 63 Fordham L. Rev.<br />

1809 (1995); Mark McDonald, Literary-Rights Fee Agreements in California: Letting the Rabbit<br />

Guard the Carrot Patch of Sixth Amendment Protection and Attorney Ethics?, 24 Loy. L.A L.<br />

Rev. 365 (1991); New York State Bar Association Ethics Op. 606 (1990). While these opinions<br />

may provide some guidance, the trial court must look at the facts of each case to make a<br />

determination whether there is an actual conflict, which is the approach our Supreme Court<br />

employed in Pelley. See Pelley, 901 N.E.2d at 507 (rejecting counsel's argument that an<br />

appearance of impropriety was sufficient to remove a prosecutor).<br />

<strong>The</strong> facts in the instant case simply do not establish an actual conflict by clear and<br />

convincing evidence. Although Henderson had signed a contract with a literary agent between<br />

the guilty verdict and sentencing, this type of an agreement is not prohibited by Rule 1.8( d).<br />

After the Defendant had been sentenced, Henderson had no further discretionary responsibilities,<br />

but rather the Attorney General represented the State during the appeal. <strong>The</strong> project was nothing<br />

more than a proposal until June 3, 2009, when Weimann negotiated a publishing agreement<br />

between Henderson and Penguin (Exh. GIS; Exh. H.B). Our Supreme Court reversed Camm II<br />

on June 26, 2009. Camm 11,908 N.E.2d at 215. Within a month, while the State's rehearing<br />

petition was pending, Penguin agreed with Henderson's suggestion that the best solution was to<br />

void the contract and for Henderson to repay the advance (Exh. F.I). It took a few weeks to<br />

prepare the termination paperwork, which was completed by September 2009 (Exh. E 51).<br />

Henderson and DiMarco returned the advance by the first week in October (Exh. G 50). Thus,<br />

the evidence supports the trial court's conclusion that there is no current book deal and,<br />

accordingly, no actual conflict of interest CAppo 251).<br />

21

Few cases have addressed whether a prosecutor's book deal creates a conflict of interest<br />

at all, let alone a book deal that was terminated before it ever really began. <strong>The</strong> true crime genre<br />

first appeared in 1965 in Truman Capote's book In Cold Blood (Signet 1965).7 Prosecutors<br />

began writing true crime books from the prosecutor's perspective in approximately 1975 when<br />

Vincent Bugliosi wrote about the Tate-LaBianca murders in Helter Skelter: <strong>The</strong> True Story of the<br />

Manson Murders (Bantam 1975). Bugliosi also wrote about a murder on the Palmyra atoll in a<br />

book entitled And the Sea Will Tell: Murder on a Desert Island and Justice (Norton 1991).<br />

Noted legal commentator Jeffrey Toobin penned Opening Arguments: A Young <strong>Law</strong>yer's First<br />

Case (Viking 1991) arising from his work as a young prosecutor during the Iran-Contra affair.<br />

Though the New York Times criticized Toobin for writing the book, 8 no disciplinary action ever<br />

resulted from the book and attempts by the special prosecutor to prevent publication wholly<br />

failed. See generally Pengui,l Books USA, Inc. v. Walsh, 756 F. Supp. 770 (S.D.N.Y. 1991),<br />

vacated as moot, 929 F.2d 69 (2nd Cir. 1991). Using Mark Twain's humorist approach, noted<br />

Missouri prosecutor Morley Swingle has written about numerous cases he prosecuted. See<br />

Scoundrels to the Hoosegow: Perry Mason Moments and Entertaining Cases from the Files of a<br />

Prosecuting Attorney (University of Missouri Press 2007). Books by prosecutors are, therefore,<br />

not as rare as Defendant claims.<br />

7 Writer Tom Wolfe has written an excellent essay criticizing Capote's approach. See<br />

Pornoviolence in Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine and other stories, sketches and<br />

essays 178-87 (Farrar 1976). Of Wolfe's categories - the "who done it," the "never been<br />

caught," and Capote's new "gory details" - the latter bases its suspense upon promising the<br />

details of cases and waiting to tell them until the very end of the book. Id. at 185. Wolfe also<br />

criticized the genre for rarely telling a story from the victim's point of view. Id. at 183.<br />

8 See John P. MacKenzie, "Peddling Iran-Contra Secrets," New York Times Editorial (February<br />

8, 1991) available at: http://www.nytimes.coml1991/02/08/opinionleditorial-notebook-peddlingiran-contra-secrets.html<br />

(last visited August 8, 2011).<br />

22

Moreover, cases addressing literary rights in other jurisdictions offer some guidance to<br />

answer the question presented in this interlocutory appeal. In Haraguchi v. Superior Court, 182<br />

P.3d 579, 589 (Cal. 2008) (not discussed in Preventable Error, supra), a prosecutor moonlighted<br />

as a fictional novelist and published and promoted a book entitled Intoxicating Agent, which<br />

resembled Haraguchi's case. Id. at 582-83. <strong>The</strong> California court applied a two-part test<br />

determining first, whether there was a conflict of interest and, second, whether the conflict was<br />

so severe as to disqualify the prosecutor from acting. Id. at 584. To address the first part of the<br />

test, the court must answer whether the circumstances of a case established a reasonable<br />

probability that the prosecutor could not exercise its discretionary function in an evenhanded<br />

manner. Id. at 585. If a conflict exists, the court must then assess whether that conflict is so<br />

grave as to render it unlikely that defendant will receive fair treatment during all portions of the<br />

criminal proceeding. !d. <strong>The</strong> Haraguchi court reasoned that, while the prosecutor's career as a<br />

novelist might benefit from successful prosecutions, the second income stream would have no<br />

ill-effects on incentives to try, settle, or dismiss the case against Haraguchi. Haraguchi, 182<br />

P.3d at 586-88. Even if a reasonable conflict of interest existed, the Haraguchi court noted that<br />

the minimal publicity and sales did not estabHsh the likelihood of unfair treatment. Id. at 589.<br />

Only an actual likelihood of unfair treatment, not a subjective perception of impropriety, can<br />

warrant a court's taking the significant step of removing a prosecutor. Id. at 589. Similarly to<br />

Haraguchi, Henderson's rescinded book deal has had no effect on Henderson's incentive to try,<br />

settle, or dismiss the case against Defendant.<br />

In People v. Sims, 612 N.E.2d 1011 (Ill. Ct. App. 1993), Sims appealed her murder<br />

conviction in a "highly publicized case." Id. at 1018. In Sims, the prosecutor entered into an<br />

agreement with a co-author one week after the trial concluded, and signed a contract with a<br />

23

publisher one week before the final sentencing hearing. Id. <strong>The</strong> defendant wanted a book,<br />

which was written by the prosecutor and published, to be added to the record because it would<br />

show a conflict of interest, prosecutorial misconduct, undisclosed discovery violations, and<br />

possible perjury by police witnesses. Id. <strong>The</strong> Illinois Court of Appeals agreed with Sims that the<br />

request and situation was "entirely unique and no case law or other precedent in point is known<br />

to exist." Id at 1019. <strong>The</strong> court addressed whether the prosecutor's thoughts regarding future<br />

financial gain during the trial and any discussion he had regarding those thoughts were a<br />

violation of the defendant's right to a fair trial. Id. <strong>The</strong> Sims court held that those thoughts,<br />

without showing that the defendant had suffered any actual harm, were insufficient to grant a<br />

new trial. Id. Specifically, the court stated:<br />

Simply because a prosecutor, judge, or defense attorney may consider profiting<br />

from their involvement in a highly publicized trial does not necessarily mean that<br />

the prosecutor, judge, or defense attorney has engaged in conduct that violates the<br />

Code of Professional Responsibility. [ ... ] We could not find anything in the<br />

record to indicate that the trial prosecutor or the State's Attorney conducted<br />

themselves during the trial in a manner calculated to prejudice the defendant's<br />

right to a fair and impartial trial deriving from the prosecutor's contemplation of<br />

writing a book.<br />

!d. Henderson's proposed book, now rescinded, is even less problematic than Sims where the<br />

prosecutor had a signed contract to publish before the final sentencing hearing.<br />

Similarly to Sims, Defendant fails to articulate with any specificity any concrete harm<br />

which might impair his right to a fair trial. Henderson has no present contract to write a book<br />

regarding the Camm murders (Exhs. E 40,51, G 96-97). Nor is there a "wink-and-a-nod"<br />

agreement between Henderson and the publisher after the third trial (Exh. E 52,54). Even<br />

Professor Lefstein admitted that the book deal had been terminated by August of2009, and that<br />

Henderson had no contract at that time (Tr. 78, 86). Although he opined that Henderson's<br />

previous book deal continued to divide his loyalties, Lefstein conceded that Henderson was not<br />

24

violating Rule 1.8(d) at the time of the hearing (Tr. 86, 112-13). As the literary agent,<br />

Weimann, noted, an acquittal would be just as sensational as a third conviction (Exh. G 98-99).<br />

It is clear from Henderson's suggested alternate titles - "Murder in the Midwest: <strong>The</strong> Second<br />

and Final Trial of David Camm" and "Murder in the Midwest: <strong>The</strong> Final Trial of David Camm"<br />

- that he did not expect he would have to try Defendant for the third time (Exh. F.C). Moreover,<br />

Henderson never provided a m:muscript or shared any information or evidence about the case<br />

that was not already part of the public record (Exh. G 76, 84).<br />

Furthermore, it is unlikely the instant case will become more sensational than it already<br />

IS. <strong>The</strong> instant case has been on 48 Hours twice. 9 In fact, there has already been one book about<br />

the murder of Kim, Brad, and Jill.1D <strong>The</strong>re have been countless news stories about the case.<br />

Henderson's proposed book would have simply told the story of a trial from the point of view of<br />

the prosecution and the victims (Exh. F.A). <strong>Indiana</strong> criminal law has certainly had no shortage<br />

of true crime books in high profile cases and this case is no different, even if from Henderson's<br />

point of view. 11 Any special prosecutor who is appointed to the case will have the same<br />

speculative, illusory "conflict" because of the high profile nature as discussed by the Sims court.<br />

9 See 48 Hours, Murder on Lockhart Road, original air date December 9, 2006; updated July 10,<br />

2008 available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006112/07/48hours/main223 8837 .shtml<br />

(last visited August 8, 2011).<br />

10 See John Glatt, One Deadly Night (St. Martin's Press 2005).<br />

II See, e.g., Steve Miller, Girl Wanted: <strong>The</strong> Chase for Sarah Pender (Berkley 2011) (depicting<br />

an escape from <strong>Indiana</strong> Department of Correction); Thomas Henry Jones, Fear no Evil (St.<br />

Martin's Press 2002) (portraying the murder of Eldon Anson in Huntington, <strong>Indiana</strong>); Mike<br />

McCarty, Choking in Fear (Arner Book Pub 2004) (detailing murders in Waveland, <strong>Indiana</strong><br />

through the eyes of a police officer); John Dean, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Indiana</strong> Torture Slaying: Sylvia Likens'<br />

Ordeal & Death (BorfBooks 1999); Wensley Clark, Deadly Seduction (St. Martin's Press 1996)<br />

(revisiting the Jimmy Grund murder in Peru, <strong>Indiana</strong>).<br />

25

<strong>The</strong> California Supreme Court also reached a conclusion similar to Sims in Hollywood v.<br />

Superior Court, 182 P .3d 590 (Cal. 2008). In Hollywood, a prosecutor had turned over materials<br />

to a film director and screenwriter and become a consultant to a film entitled Alpha Dog. Id. at<br />

594. <strong>The</strong> defendant argued that by cooperating in the making of a movie, the prosecutor sought<br />

to "burnish his own legacy" and put himself in a position to "[expand] the market for a book of<br />

his own based on [the] case." Id. at 594,599. <strong>The</strong> court noted that, among other things, the<br />

prosecutor had decided to shelve any plans for a book as it might pose a conflict of interest. Id.<br />

at 599. <strong>The</strong> court found that the prosecutor, because of this decision, had the same interest that<br />

every attorney - both defense and prosecution - has in a high profile case. Id. <strong>The</strong> Court stated:<br />

"if the high-profile nature of a case presents incentives to handle the matter in any way contrary<br />

to the evenhanded dispensation of justice, the problem is not one that removal can solve, as the<br />

same issue would arise equally for any theoretical prosecutor." Id. While the prosecutor's<br />

decision to hand over case files was found to be sanctionable, the court held that the financial<br />

incentive presented to the prosecutor did not impair Hollywood's chance to receive a fair trial.<br />

Id. at 600. Similarly to Hollywood, even though Henderson had a previous deal for his book,<br />

also known as "Murder in the Midwest: <strong>The</strong> Second and Final Trial of David Camm," there is<br />

no longer any agreement and (IllY financial incentive is wholly speculative. Defendant's "form<br />

over substance" argument that Henderson has a contract is in direct conflict with the record as<br />

there is no book deal (Exhs. E 40,51-52, 54,G 96-97).<br />

<strong>The</strong> trial court here properly concluded that a new prosecutor was unnecessary because<br />

no conflict of interest exists which endangers a fair trial. Henderson had an agreement with a<br />

literary agent just after the trial, but no publishing contract until long after Defendant was<br />

sentenced. Henderson's literary agent contract had no effect on any decisions Henderson made<br />

26

during the second trial, just as in Sims. Even if the book deal and literary agent agreement had<br />

created a conflict of interest, as noted by the court in Haraguchi and Hollywood, the small<br />

amount of financial gain Henderson ~tood to earn could not establish the likelihood of unfair<br />

treatment at a third trial. <strong>The</strong> parties terminated the contract and the co-authors returned the<br />

$4,000 advance before our Supreme Court denied the Attorney General's petition for rehearing<br />

on November 30, 2009. 12 <strong>The</strong>se curative actions occurred nearly two full months before<br />

Henderson decided to try Defendant for a third time.<br />

A third trial would have been a foregone conclusion for any prosecutor after the split<br />

decision on rehearing where even the majority concluded there was sufficient evidence to retry<br />

Defendant. Moreover, any potential financial gain Henderson would gamer from retrying the<br />

case is speculative at best because there is no guarantee, not even a "wink-and-a-nod" agreement,<br />

that Penguin or any other publisher will publish the book Henderson originally proposed. In this<br />

case, Defendant concedes has cost the State substantial financial resources, indeed millions of<br />

dollars. If the Court concludes that Henderson should be removed, the cost to try Defendant will<br />

increase even more because Henderson's entire staffwill be excluded, which means that<br />

Defendant will have a third trial, in a third county, with a third judge, and a third prosecutor - an<br />

expensive prospect indeed. Henderson has no incentive to abandon his role as a minister of<br />

justice for the paltry sum of $1 ,700.00, which has already been returned. 13<br />

12 As a matter of professional courtesy, the Attorney General routinely invites prosecutors,<br />

deputy prosecutors, and trial counsel who represented the State's interests below the honor of<br />

sitting at counsel table during oral arguments. Occasionally, trial counsel may offer some<br />

assistance clarifying the record of proceedings. However, such limited participation has no<br />

effect on the trial record, or on retrial. Defendant is tilting at windmills when he notes that<br />

Henderson sat with the State at counsel table during the oral argument in Camm 11. See Br. of<br />

Appellant 3; Exhs. C, D.<br />

13 Defendant also takes issue with Henderson's statement that he "immediately" terminated the<br />

publishing contract, claiming Henderson defrauded the court. See Br. of Appellant 28. Whether<br />

27

Defendant's reliance on Tippecanoe County Court, 432 N.E.2d 1377 (Ind. 1982) is<br />