Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

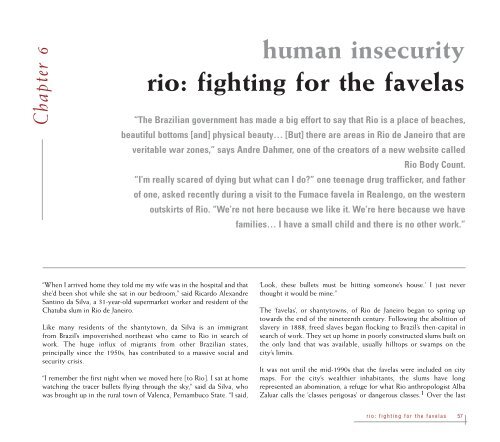

Chapter 6<br />

human insecurity<br />

rio: <strong>fighting</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>favelas</strong><br />

“The Brazilian government has made a big ef<strong>for</strong>t to say that <strong>Rio</strong> is a place of beaches,<br />

beautiful bottoms [and] physical beauty… [But] <strong>the</strong>re are areas in <strong>Rio</strong> de Janeiro that are<br />

veritable war zones,” says Andre Dahmer, one of <strong>the</strong> creators of a new website called<br />

<strong>Rio</strong> Body Count.<br />

“I’m really scared of dying but what can I do?” one teenage drug trafficker, and fa<strong>the</strong>r<br />

of one, asked recently during a visit to <strong>the</strong> Fumace favela in Realengo, on <strong>the</strong> western<br />

outskirts of <strong>Rio</strong>. “We’re not here because we like it. We’re here because we have<br />

families… I have a small child and <strong>the</strong>re is no o<strong>the</strong>r work.”<br />

“When I arrived home <strong>the</strong>y told me my wife was in <strong>the</strong> hospital and that<br />

she’d been shot while she sat in our bedroom,” said Ricardo Alexandre<br />

Santino da Silva, a 31-year-old supermarket worker and resident of <strong>the</strong><br />

Chatuba slum in <strong>Rio</strong> de Janeiro.<br />

Like many residents of <strong>the</strong> shantytown, da Silva is an immigrant<br />

from Brazil’s impoverished nor<strong>the</strong>ast who came to <strong>Rio</strong> in search of<br />

work. The huge influx of migrants from o<strong>the</strong>r Brazilian states,<br />

principally since <strong>the</strong> 1950s, has contributed to a massive social and<br />

security crisis.<br />

“I remember <strong>the</strong> first night when we moved here [to <strong>Rio</strong>]. I sat at home<br />

watching <strong>the</strong> tracer bullets flying through <strong>the</strong> sky,” said da Silva, who<br />

was brought up in <strong>the</strong> rural town of Valenca, Pernambuco State. “I said,<br />

‘Look, <strong>the</strong>se bullets must be hitting someone’s house.’ I just never<br />

thought it would be mine.”<br />

The ‘<strong>favelas</strong>’, or shantytowns, of <strong>Rio</strong> de Janeiro began to spring up<br />

towards <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century. Following <strong>the</strong> abolition of<br />

slavery in 1888, freed slaves began flocking to Brazil’s <strong>the</strong>n-capital in<br />

search of work. They set up home in poorly constructed slums built on<br />

<strong>the</strong> only land that was available, usually hilltops or swamps on <strong>the</strong><br />

city’s limits.<br />

It was not until <strong>the</strong> mid-1990s that <strong>the</strong> <strong>favelas</strong> were included on city<br />

maps. For <strong>the</strong> city’s wealthier inhabitants, <strong>the</strong> slums have long<br />

represented an abomination, a refuge <strong>for</strong> what <strong>Rio</strong> anthropologist Alba<br />

Zaluar calls <strong>the</strong> ’classes perigosas’ or dangerous classes. 1 Over <strong>the</strong> last<br />

r i o : f i g h t i n g f o r t h e f a v e l a s 57