Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya (National ... - IGRMS

Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya (National ... - IGRMS

Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya (National ... - IGRMS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

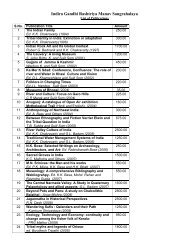

<strong>Indira</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Rashtriya</strong> <strong>Manav</strong> <strong>Sangrahalaya</strong> 277<br />

for a closed circle. In Europe and in most colonial territories, museums and art<br />

galleries began at a time when the people who controlled them had a contempt<br />

for the masses’ (Hudson 1977: 7). Many of the museums developed in the western<br />

world in the 18 th century had inherited this outlook, and remained as such for a<br />

long. The ethnological museums ‘invented’ by European colonizers in the 19 th<br />

century, in course of their expeditions to the rest of the world, had presented<br />

their collection of objects as either curio-items, or as proof of emphasis that the<br />

culture of colonized communities were ‘inferior’ or ‘peripheral’ to the technological<br />

achievements of Europe.<br />

The seventies of 20th century was a decade of crucial developments in the<br />

history of museums and museology all over the world. This was the period when<br />

independent countries, including India, began to settle down. New nationalism<br />

and cultural identities began to emerge among the liberated countries. In the<br />

newly independent countries, the role of museums began to firm-up during this<br />

period as important cultural centers for asserting national and regional identities.<br />

In the 1971 General Conference of the International Council of Museums<br />

(ICOM) held in France (at Grenoble), an African delegate from Benin, made a<br />

statement with considerable heat and vigour. ‘Museums’, he said, ‘were not<br />

integrated into the contemporary world and formed no real part of it. They were<br />

elitist, and of no use whatever to the majority of people; in all countries, they<br />

were obsolete; and they ought to disappear so that the public money could be<br />

spent to better purpose’. There were many takers of this passionate statement.<br />

The conclusion reached at the 1971 ICOM Conference was that the social,<br />

economic and cultural changes occurring in the world, particularly in many underprivileged<br />

regions, constitute a challenge to museology. The future historians of<br />

museums and museology may well decide that 1971 was the year in which it<br />

became obvious that there would have to be fundamental changes in the philosophy<br />

and aims of museums, and that the traditional attitudes were inadequate and<br />

obsolete in demonstrating the contemporary relevance of museum. It was felt<br />

that a museum should mould the consciousness of the communities it serves,<br />

link together the past and present. However, there was no suggestions that existing<br />

specialized museums should be closed down or abandoned, but, to meet the<br />

social needs, it was felt that there should be a gradual change in the outlook of<br />

curators and administrators, so that a steady progress towards ‘integrated museum’<br />

might be ensured. Integrated museum approach meant a realization that it exists<br />

to meet the needs of people, not merely to preserve what the French call the<br />

patrimone, the national cultural heritage’. (Hudson 1977:15).<br />

Birth of <strong>IGRMS</strong>: Initial Ideas and Concepts<br />

The birth of ‘<strong>National</strong> Museum of Man’ in India was a sequel of these<br />

developments. In the Calcutta session of the Indian Science Congress, held in<br />

1970, Sachin Roy, President of the Anthropology and Archaeology Section,