The Business Model Ontology - a proposition in a design ... - HEC

The Business Model Ontology - a proposition in a design ... - HEC

The Business Model Ontology - a proposition in a design ... - HEC

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

3 KNOWLEDGE OF THE PROBLEM DOMAIN<br />

<strong>The</strong> two ma<strong>in</strong> doma<strong>in</strong>s that serve as a foundation for this thesis are management theory and<br />

Information Systems. More precisely, the first part of the dissertation treat<strong>in</strong>g of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model<br />

ontology (section 4) is built on <strong>in</strong>puts from bus<strong>in</strong>ess model literature <strong>in</strong> management theory and<br />

enterprise ontologies <strong>in</strong> IS. <strong>The</strong> part of the dissertation treat<strong>in</strong>g of bus<strong>in</strong>ess strategy, IS alignment and<br />

e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess essentially draws from alignment theory <strong>in</strong> IS (section 8.1).<br />

3.1 BUSINESS MODEL LITERATURE<br />

In this section I explore the exist<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess model literature. <strong>The</strong> material treat<strong>in</strong>g of bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models ranges from bus<strong>in</strong>ess model def<strong>in</strong>itions, components, taxonomies, <strong>design</strong> tools, change<br />

methodologies to evaluation measures.<br />

Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, the ma<strong>in</strong>stream appearance of the term bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is a relatively young phenomenon<br />

that has found its first peak dur<strong>in</strong>g the Internet hype at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of this millennium. A query <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> Source Premier, a lead<strong>in</strong>g electronic database for bus<strong>in</strong>ess magaz<strong>in</strong>es and scholarly bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

journals, shows that the term appeared <strong>in</strong> 1960 <strong>in</strong> the title and the abstract of a paper <strong>in</strong> the Account<strong>in</strong>g<br />

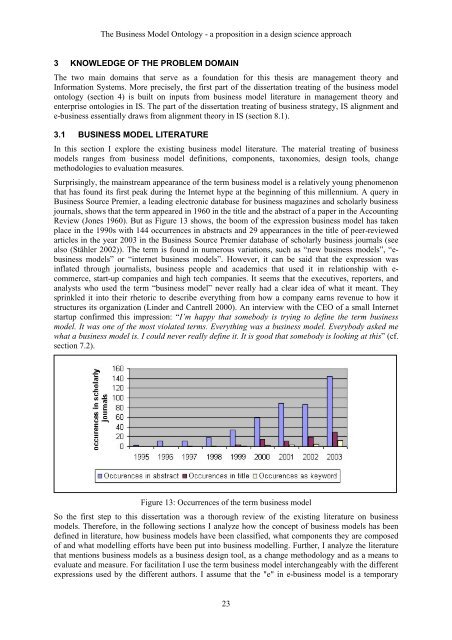

Review (Jones 1960). But as Figure 13 shows, the boom of the expression bus<strong>in</strong>ess model has taken<br />

place <strong>in</strong> the 1990s with 144 occurrences <strong>in</strong> abstracts and 29 appearances <strong>in</strong> the title of peer-reviewed<br />

articles <strong>in</strong> the year 2003 <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> Source Premier database of scholarly bus<strong>in</strong>ess journals (see<br />

also (Stähler 2002)). <strong>The</strong> term is found <strong>in</strong> numerous variations, such as “new bus<strong>in</strong>ess models”, “ebus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models” or “<strong>in</strong>ternet bus<strong>in</strong>ess models”. However, it can be said that the expression was<br />

<strong>in</strong>flated through journalists, bus<strong>in</strong>ess people and academics that used it <strong>in</strong> relationship with e-<br />

commerce, start-up companies and high tech companies. It seems that the executives, reporters, and<br />

analysts who used the term “bus<strong>in</strong>ess model” never really had a clear idea of what it meant. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

spr<strong>in</strong>kled it <strong>in</strong>to their rhetoric to describe everyth<strong>in</strong>g from how a company earns revenue to how it<br />

structures its organization (L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell 2000). An <strong>in</strong>terview with the CEO of a small Internet<br />

startup confirmed this impression: “I’m happy that somebody is try<strong>in</strong>g to def<strong>in</strong>e the term bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

model. It was one of the most violated terms. Everyth<strong>in</strong>g was a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. Everybody asked me<br />

what a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is. I could never really def<strong>in</strong>e it. It is good that somebody is look<strong>in</strong>g at this” (cf.<br />

section 7.2).<br />

Figure 13: Occurrences of the term bus<strong>in</strong>ess model<br />

So the first step to this dissertation was a thorough review of the exist<strong>in</strong>g literature on bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models. <strong>The</strong>refore, <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g sections I analyze how the concept of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models has been<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> literature, how bus<strong>in</strong>ess models have been classified, what components they are composed<br />

of and what modell<strong>in</strong>g efforts have been put <strong>in</strong>to bus<strong>in</strong>ess modell<strong>in</strong>g. Further, I analyze the literature<br />

that mentions bus<strong>in</strong>ess models as a bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>design</strong> tool, as a change methodology and as a means to<br />

evaluate and measure. For facilitation I use the term bus<strong>in</strong>ess model <strong>in</strong>terchangeably with the different<br />

expressions used by the different authors. I assume that the "e" <strong>in</strong> e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is a temporary<br />

23

Knowledge of the Problem Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

phenomenon that will disappear <strong>in</strong> time because most bus<strong>in</strong>ess models will have some ICT<br />

component.<br />

Authors<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>ition<br />

Taxonomy<br />

Components<br />

Representation<br />

Tool<br />

Ontological<br />

<strong>Model</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Change<br />

Methodology<br />

Evaluation<br />

Measures<br />

(Afuah and Tucci 2001; 2003) X X X<br />

(Alt and Zimmermann 2001) X X<br />

(Amit and Zott 2001)<br />

(Applegate 2001) X X<br />

(Bagchi and Tulskie 2000)<br />

(Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2000)<br />

(Gordijn 2002) X X X X<br />

(Hamel 2000) X X<br />

(Hawk<strong>in</strong>s 2001)<br />

(L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell 2000) X X X X<br />

(Magretta 2002) X X<br />

(Mahadevan 2000)<br />

(Maitland and Van de Kar 2002)<br />

(Papakiriakopoulos and Poulymenakou 2001)<br />

(Peterovic, Kittl et al. 2001) X X X<br />

(Rappa 2001) X X<br />

(Stähler 2002)<br />

(Tapscott, Ticoll et al. 2000) X X X X<br />

(Timmers 1998) X X<br />

(Weill and Vitale 2001) X X X X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

Table 2: <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> model authors list (partially based on (Pateli 2002))<br />

Table 2 summarizes the contributions of the most important bus<strong>in</strong>ess model authors. <strong>The</strong> first two<br />

columns of the table name author and year of contribution and the follow<strong>in</strong>g columns reveal the major<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess model areas covered and whether a specific author has contributed to this area. <strong>The</strong> first<br />

"def<strong>in</strong>ition" column shows if an author provides a short comprehensible def<strong>in</strong>ition of what a bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

model is. <strong>The</strong> "taxonomy" column <strong>in</strong>dicates which authors propose a classification of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models.<br />

<strong>The</strong> "components" column po<strong>in</strong>ts out authors that go beyond a simple def<strong>in</strong>ition and classification of<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess models by present<strong>in</strong>g a conceptual approach to bus<strong>in</strong>ess models, propos<strong>in</strong>g a set of bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

model components. Simply put, they specify of what a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is composed of. <strong>The</strong><br />

"representation tool" column specifies authors that offer a set of tools or graphical representations to<br />

<strong>design</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess models. <strong>The</strong> "ontological modell<strong>in</strong>g" column <strong>in</strong>dicates authors that use a rigorous<br />

modell<strong>in</strong>g approach to bus<strong>in</strong>ess models. Authors present <strong>in</strong> this category provide an ontology that<br />

carefully def<strong>in</strong>es bus<strong>in</strong>ess model concepts, components and relationships among components. <strong>The</strong><br />

"change methodology" column po<strong>in</strong>ts to authors <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a time and change component <strong>in</strong> their<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess model concepts. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the "evaluation measures" column <strong>in</strong>dicates authors that try to<br />

def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dicators to measure the success of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models.<br />

24<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

3.1.1 <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Def<strong>in</strong>itions<br />

<strong>The</strong> first column of Table 2 covers bus<strong>in</strong>ess model def<strong>in</strong>itions. Paul Timmers, then work<strong>in</strong>g for the<br />

European Commission, was one of the first to explicitly def<strong>in</strong>e and classify bus<strong>in</strong>ess models (Timmers<br />

1998). He understands a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model as the architecture for the product, service and <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

flows, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a description of the various bus<strong>in</strong>ess actors and their roles and a description of the<br />

potential benefits for the various bus<strong>in</strong>ess actors and a description of the sources of revenues. In order<br />

to understand how a company realizes its bus<strong>in</strong>ess mission he adds a market<strong>in</strong>g model that is the<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ation of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model and the market<strong>in</strong>g strategy of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess actor under<br />

consideration. Like Timmers, Weill and Vitale (Weill and Vitale 2001) def<strong>in</strong>e a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model as a<br />

description of the roles and relationships among a firm’s consumers, customers, allies and suppliers<br />

and it identifies the major flows of product, <strong>in</strong>formation, and money, as well as the major benefits to<br />

participants.<br />

In their bus<strong>in</strong>ess model def<strong>in</strong>ition L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell (2000) from the Accenture Institute for Strategic<br />

Change differentiate between three different types of models: the components of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model,<br />

real operat<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess models and change models. <strong>The</strong>y def<strong>in</strong>e a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model as an organization’s<br />

core logic for creat<strong>in</strong>g value. Similarly, Petrovic, Kittl et al. (2001) perceive bus<strong>in</strong>ess models as the<br />

logic of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess system for creat<strong>in</strong>g value. <strong>The</strong>y specify that this is <strong>in</strong> opposition to a description of<br />

a complex social system itself with all its actors, relations and processes. Referr<strong>in</strong>g to this Gordijn,<br />

Akkermans et al. (2000) mention that <strong>in</strong> research as well as <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry practice, often bus<strong>in</strong>ess models<br />

are wrongly understood as bus<strong>in</strong>ess process models, and so can be specified us<strong>in</strong>g UML activity<br />

diagrams or Petri nets. <strong>The</strong>y expla<strong>in</strong> that this is a misunderstand<strong>in</strong>g and that a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is not<br />

about processes but about value exchanged between actors. In their op<strong>in</strong>ion the failure to make this<br />

separation leads to poor bus<strong>in</strong>ess decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>adequate bus<strong>in</strong>ess requirements.<br />

Like Petrovic, Kittl et al. (2001) Applegate (2001) perceives a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model as a description of a<br />

complex bus<strong>in</strong>ess that enables the study of its structure, of the relationships among structural elements,<br />

and of how it will respond to the real world. In this regard Stähler (2002) rem<strong>in</strong>ds that a model is<br />

always a simplification of the complex reality. It helps to understand the fundamentals of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess or<br />

to plan how a future bus<strong>in</strong>ess should look like. Magretta (2002) adds that a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is like a<br />

story that expla<strong>in</strong>s how an enterprise works. And like Stähler she dist<strong>in</strong>guishes the concept of bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models from the concept of strategy. She expla<strong>in</strong>s that bus<strong>in</strong>ess models describe, as a system, how the<br />

pieces of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess fit together, but as opposed to strategy do not <strong>in</strong>clude performance and<br />

competition.<br />

Tapscott, Ticoll et al. (2000) do not directly def<strong>in</strong>e bus<strong>in</strong>ess models, but what they call b-webs<br />

(bus<strong>in</strong>ess webs). A b-web is a bus<strong>in</strong>ess on the <strong>in</strong>ternet and represents a dist<strong>in</strong>ct system of suppliers,<br />

distributors, commerce service providers, <strong>in</strong>frastructure providers, and customers that use the Internet<br />

for their primary bus<strong>in</strong>ess communication and transactions. Similarly, another highly networkcentered<br />

approach is provided by Amit and Zott (2001). <strong>The</strong>y describe a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model as the<br />

architectural configuration of the components of transactions <strong>design</strong>ed to exploit bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

opportunities. <strong>The</strong>ir framework depicts the ways <strong>in</strong> which transactions are enabled by a network of<br />

firms, suppliers, complementors and customers.<br />

A series of authors <strong>in</strong>troduce a f<strong>in</strong>ancial element <strong>in</strong>to their def<strong>in</strong>itions. Afuah and Tucci (2003) state<br />

that each firm that exploits the Internet should have an Internet bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. <strong>The</strong>y understand it as<br />

a set of Internet- and non-Internet-related activities that allow a firm to make money <strong>in</strong> a susta<strong>in</strong>able<br />

way. Hawk<strong>in</strong>s (2001) describes a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model as the commercial relationship between a bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

enterprise and the products and/or services it provides <strong>in</strong> the market. He expla<strong>in</strong>s that it is a way of<br />

structur<strong>in</strong>g various cost and revenue streams such that a bus<strong>in</strong>ess becomes viable, usually <strong>in</strong> the sense<br />

of be<strong>in</strong>g able to susta<strong>in</strong> itself on the basis of <strong>in</strong>come it generates. Rappa (2001) def<strong>in</strong>es a bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

model as the method of do<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess by which a company can susta<strong>in</strong> itself -- that is, generate<br />

revenue. For him the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model spells-out how a company makes money by specify<strong>in</strong>g where it<br />

is positioned <strong>in</strong> the value cha<strong>in</strong>.<br />

25

Knowledge of the Problem Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

3.1.2 <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Taxonomies<br />

Apart from def<strong>in</strong>itions a number of authors provide us with bus<strong>in</strong>ess model taxonomies. This means<br />

that they classify bus<strong>in</strong>ess models with a certa<strong>in</strong> number of common characteristics <strong>in</strong> a set of different<br />

categories. <strong>The</strong> probably best known classification scheme and def<strong>in</strong>ition of electronic bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models is the one of Timmers (1998). He dist<strong>in</strong>guishes between eleven generic e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess models and<br />

classifies them accord<strong>in</strong>g to their degree of <strong>in</strong>novation and their functional <strong>in</strong>tegration (see Figure 14).<br />

<strong>The</strong> models are e-shops, e-procurement, e-malls, e-auctions, virtual communities, collaboration<br />

platforms, third-party marketplaces, value cha<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrators, value-cha<strong>in</strong> service providers, <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

brokerage and trust and other third-party services (see Table 3).<br />

Multiple<br />

Functions/<br />

Integrated<br />

Value Cha<strong>in</strong> Integrator<br />

Third Party Marketplace<br />

Degree of<br />

Integration<br />

E-Procurement<br />

E-Mall<br />

Collaboration Platform<br />

Virtual Community<br />

Value Cha<strong>in</strong> Service Provider<br />

E-Auction<br />

E-Shop<br />

Trust Services<br />

S<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

Function<br />

lower<br />

Degree of Innovation<br />

Info Brokerage<br />

higher<br />

Figure 14: Figure: Timmer’s (1998) classification scheme<br />

Category<br />

e-Shops<br />

e-Procurement<br />

e-Malls<br />

e-Auctions<br />

Virtual communities<br />

Collaboration<br />

platforms<br />

Third-party<br />

marketplaces<br />

Value cha<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrators<br />

Value-cha<strong>in</strong> service<br />

providers<br />

Information<br />

brokerage<br />

Trust and other<br />

Description<br />

Stands for the Web market<strong>in</strong>g and promotion of a company or a shop and<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>cludes the possibility to order and to pay.<br />

Describes electronic tender<strong>in</strong>g and procurement of goods and services.<br />

Stands for the electronic implementation of the bidd<strong>in</strong>g mechanism also known<br />

from traditional auctions.<br />

Consists of a collection of e-shops, usually enhanced by a common umbrella, for<br />

example a well-known brand.<br />

This model br<strong>in</strong>gs together virtual communities that contribute value <strong>in</strong> a basic<br />

environment provided by the virtual community operator. Membership fees and<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g generate revenues. It can also be found as an add-on to other<br />

market<strong>in</strong>g operations for customer feedback or loyalty build<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Companies of this group provide a set of tools and <strong>in</strong>formation environment for<br />

collaboration between enterprises.<br />

A model that is suitable when a company wishes to leave the Web market<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

a 3 rd party (possibly as an add-on to their other channels). Third-party<br />

marketplaces offer a user <strong>in</strong>terface to the supplier's product catalogue.<br />

Represents the companies that focus on <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g multiple steps of the value<br />

cha<strong>in</strong>, with the potential to exploit the <strong>in</strong>formation flow between those steps as<br />

further added value.<br />

Stands for companies that specialize on a specific function for the value cha<strong>in</strong>,<br />

such as electronic payment or logistics.<br />

Embraces a whole range of new <strong>in</strong>formation services that are emerg<strong>in</strong>g to add<br />

value to the huge amounts of data available on the open networks or com<strong>in</strong>g<br />

from <strong>in</strong>tegrated bus<strong>in</strong>ess operations.<br />

Stands for trust services, such as certification authorities and electronic notaries<br />

26

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

third-party services<br />

and other trusted third parties.<br />

Table 3: Timmer’s architectures of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models (Timmers 1998)<br />

Alt and Zimmermann (2001) po<strong>in</strong>t out that there are two major categories of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models, one<br />

based on the object of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model and the other based on the purpose of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first group <strong>in</strong>cludes market and role models, sector and <strong>in</strong>dustry models and f<strong>in</strong>ally revenue<br />

models. <strong>The</strong> second group <strong>in</strong>cludes bus<strong>in</strong>ess models, reference models and simulation models.<br />

Tapscott et al. (2000) proposes a network- and value-centered taxonomy that dist<strong>in</strong>guishes between<br />

five types of value networks, which differ <strong>in</strong> their degree of economic control and value <strong>in</strong>tegration<br />

(see Figure 15 and Table 4). <strong>The</strong>y call these types b-webs (bus<strong>in</strong>ess webs). <strong>The</strong> first one, the so-called<br />

Agora facilitates exchange between buyers and sellers, who jo<strong>in</strong>tly discover a price through on-thespot<br />

negotiations (e.g. eBay). In the second type, the Aggregation b-web, one company leads <strong>in</strong><br />

hierarchical fashion, position<strong>in</strong>g itself as a value-add<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>termediary between producers and<br />

customers (e.g. Amazon.com). In the third b-web, the Value Cha<strong>in</strong>, a context provider structures and<br />

directs the network to produce highly <strong>in</strong>tegrated value <strong>proposition</strong>s (e.g. Dell). <strong>The</strong> fourth network, the<br />

Alliance, strives for high value <strong>in</strong>tegration without hierarchical control (e.g. L<strong>in</strong>ux). <strong>The</strong> last type,<br />

Distributive Networks, keeps the economy alive and mobile (e.g. FedEx).<br />

Self-organiz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

CONTROL<br />

Agora<br />

Aggregation<br />

Distributive<br />

Network<br />

Alliance<br />

Value Cha<strong>in</strong><br />

Hierarchical<br />

Low<br />

VALUE INTEGRATION<br />

High<br />

Type of b-web<br />

Agora<br />

Aggregation<br />

Value Cha<strong>in</strong><br />

Alliance<br />

Distributive Network<br />

Figure 15: b-webs (Tapscott, Ticoll et al. 2000)<br />

Description<br />

Applies to markets where buyers and sellers meet to freely negotiate and<br />

assign value to goods. An Agora facilitates exchange between buyers and<br />

sellers, who jo<strong>in</strong>tly "discover" a price. Because sellers may offer a wide and<br />

often unpredictable variety or quantity of goods, value <strong>in</strong>tegration is low.<br />

In Aggregation b-webs there is a leader that takes responsibility for select<strong>in</strong>g<br />

products and services, target<strong>in</strong>g market segments, sett<strong>in</strong>g prices, and ensur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

fulfillment. This leader typically sets prices <strong>in</strong> advance and offers a diverse<br />

variety of products and services, with zero to limited value <strong>in</strong>tegration.<br />

In a Value Cha<strong>in</strong>, the so-called context provider structures and directs a b-web<br />

network to produce a highly <strong>in</strong>tegrated value <strong>proposition</strong>. <strong>The</strong> seller has the<br />

f<strong>in</strong>al say <strong>in</strong> pric<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

An Alliance strives for high value <strong>in</strong>tegration without hierarchical control. Its<br />

participants <strong>design</strong> goods or services, create knowledge, or simply produces<br />

dynamic, shared experiences. Alliances typically depend on rules and<br />

standards that govern <strong>in</strong>teraction, acceptable participant behavior, and the<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ation of value.<br />

Distributive Networks are b-webs that keep the economy alive and mobile.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y play a vital role <strong>in</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>g the healthy balance of the systems that they<br />

support. Distributive Networks service the other types of b-webs by allocat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and deliver<strong>in</strong>g goods.<br />

Table 4: Taxonomy of b-webs (Tapscott, Ticoll et al. 2000)<br />

27

Knowledge of the Problem Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell (2000) propose categoriz<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess models focus<strong>in</strong>g on two ma<strong>in</strong> dimensions,<br />

which are a model’s core, profit-mak<strong>in</strong>g activity, and its relative position on the price/value cont<strong>in</strong>uum<br />

(see Table 5).<br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Category<br />

Price <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Convenience <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Commodity-Plus <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Experience <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Channel <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Intermediary <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Trust <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Innovation <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Buy<strong>in</strong>g Club, One-stop, low-price shopp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Fee for advertis<strong>in</strong>g, Razor and blade<br />

One-stop, convenient shopp<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

Comprehensive offer<strong>in</strong>g, Instant gratification<br />

Low-price reliable commodity, Mass customised<br />

commodity, Service-wrapped commodity<br />

Experience sell<strong>in</strong>g, Cool brands<br />

Channel maximisation, Quality sell<strong>in</strong>g, Value-added reseller<br />

Market aggregation, Open market-mak<strong>in</strong>g, Multi-party<br />

market aggregation<br />

Trusted operations, Trusted product leadership, Trusted<br />

service leadership<br />

Incomparable products, Incomparable services,<br />

Breakthrough markets<br />

Table 5: L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell’s (2000) categorization of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models<br />

Weill and Vitale (2001) describe eight so-called atomic bus<strong>in</strong>ess models. Each model describes a<br />

different way of conduct<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess electronically. <strong>The</strong>y describe these atomic e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess models as<br />

the basic build<strong>in</strong>g blocks of an e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>itiative (see Table 6).<br />

Atomic <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong><br />

Content Provider<br />

Direct to Customer<br />

Full-Service Provider<br />

Intermediary<br />

Shared Infrastructure<br />

Value net Integrator<br />

Virtual Community<br />

Whole-of-<br />

Enterprise/Government<br />

Description<br />

Content providers are firms that create and provide content (<strong>in</strong>formation,<br />

products, or services) <strong>in</strong> digital form to customers via third parties.<br />

In this model, the buyer and seller <strong>in</strong>teract directly often bypass<strong>in</strong>g traditional<br />

channel members.<br />

Firms <strong>in</strong> this category provide total coverage of customer needs <strong>in</strong> a particular<br />

doma<strong>in</strong>, consolidated via a s<strong>in</strong>gle po<strong>in</strong>t of contact. Doma<strong>in</strong>s cover any area<br />

where customer needs cover multiple products and services, such as f<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

services or health care.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>termediary l<strong>in</strong>ks multiple buyers and sellers. Usually the sellers pay the<br />

<strong>in</strong>termediary list<strong>in</strong>g fees and sell<strong>in</strong>g commissions and it is possible that the<br />

buyer may also pay a purchase or membership fee. Advertisers also provide<br />

revenue for <strong>in</strong>termediaries. <strong>The</strong>re are six major classes of <strong>in</strong>termediaries,<br />

namely electronic mall, shopp<strong>in</strong>g agents, specialty auctions, portals, electronic<br />

auctions and electronic markets.<br />

In this atomic bus<strong>in</strong>ess model a firm provides <strong>in</strong>frastructure shared by its<br />

owners. <strong>The</strong> shared <strong>in</strong>frastructure generally offers a service that is not already<br />

available <strong>in</strong> the marketplace, and it may also be a defensive move to thwart<br />

potential dom<strong>in</strong>ation by another major player.<br />

<strong>The</strong> value net <strong>in</strong>tegrator coord<strong>in</strong>ates product flows from suppliers to allies and<br />

customers. He strives to own the customer relationship with the other<br />

participants <strong>in</strong> the model, thus know<strong>in</strong>g more about their operations than any<br />

other player. His ma<strong>in</strong> role is coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g the value cha<strong>in</strong>.<br />

In this model the firm is <strong>in</strong> the center, positioned between members of the<br />

community and suppliers. Fundamental to the success of this model is that<br />

members are able to communicate with each other directly.<br />

<strong>The</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle po<strong>in</strong>t of contact for the e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess customer is the essence of the<br />

whole-of-enterprise atomic bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. This model plays an important<br />

28

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

role <strong>in</strong> public-sector organizations but also applies to the private sector.<br />

Table 6: Weill and Vitale’s (2001) atomic bus<strong>in</strong>ess models<br />

For Rappa (2001) a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model spells-out how a company makes money by specify<strong>in</strong>g where it is<br />

positioned <strong>in</strong> the value cha<strong>in</strong>. His classification scheme consists of n<strong>in</strong>e generic forms of e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models, which are Brokerage, Advertis<strong>in</strong>g, Infomediary, Merchant, Manufacturer, Affiliate,<br />

Community, Subscription and Utility (see Table 7). <strong>The</strong>se generic models essentially classify<br />

companies among the nature of their value <strong>proposition</strong> or their mode of generat<strong>in</strong>g revenues (e.g.<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g, subscription or utility model).<br />

Type of <strong>Model</strong> Subcategories Description<br />

Brokerage<br />

<strong>Model</strong><br />

Advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Model</strong><br />

Infomediary<br />

<strong>Model</strong><br />

Merchant<br />

<strong>Model</strong><br />

Manufacturer<br />

<strong>Model</strong><br />

Affiliate <strong>Model</strong><br />

Community<br />

<strong>Model</strong><br />

Subscription<br />

<strong>Model</strong><br />

Utility <strong>Model</strong><br />

Marketplace Exchange, <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong><br />

Trad<strong>in</strong>g Community, Buy/ Sell<br />

Fulfilment, Demand Collection<br />

System, Auction Broker, Transaction<br />

Broker, Bounty Broker, Distributor,<br />

Search Agent, Virtual Mall<br />

Portal, Personalised Portal, Niche<br />

Portal, Classifieds, Registered Users,<br />

Query-based Paid Placement,<br />

Contextual Advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Advertis<strong>in</strong>g Networks, Audience<br />

Measurement Services, Incentive<br />

Market<strong>in</strong>g, Metamediary<br />

Virtual Merchant, Catalog Merchant,<br />

Click and Mortar, Bit Vendor<br />

Brand Integrated Content<br />

Voluntary Contributor <strong>Model</strong>,<br />

Knowledge Networks<br />

Content Services, Person-to-Person<br />

Network<strong>in</strong>g Services, Trust Services,<br />

Internet Service Providers<br />

<strong>The</strong>y br<strong>in</strong>g buyers and sellers together and<br />

facilitate transactions. Usually, a broker<br />

charges a fee or commission for each<br />

transaction it enables.<br />

<strong>The</strong> broadcaster, <strong>in</strong> this case a web site,<br />

provides content (usually for free) and services<br />

(like email, chat, forums) mixed with<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g messages <strong>in</strong> the form of banner<br />

ads. <strong>The</strong> banner ads may be the major or sole<br />

source of revenue for the broadcaster. <strong>The</strong><br />

broadcaster may be a content creator or a<br />

distributor of content created elsewhere.<br />

Some firms function as <strong>in</strong>fomediaries<br />

(<strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong>termediaries) by either<br />

collect<strong>in</strong>g data about consumers or collect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

data about producers and their products.<br />

Wholesalers and retailers of goods and<br />

services.<br />

Manufacturers can reach buyers directly and<br />

thereby compress the distribution channel.<br />

<strong>The</strong> affiliate model provides purchase<br />

opportunities wherever people may be surf<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

It does this by offer<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>centives (<strong>in</strong><br />

the form of a percentage of revenue) to<br />

affiliated partner sites. <strong>The</strong> affiliates provide<br />

purchase-po<strong>in</strong>t click-through to the merchant<br />

via their web sites.<br />

<strong>The</strong> community model is based on user<br />

loyalty. Users have a high <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> time<br />

and emotion <strong>in</strong> the site. In some cases, users<br />

are regular contributors of content and/or<br />

money.<br />

Users are charged a periodic – daily, monthly<br />

or annual – fee to subscribe to a service.<br />

<strong>The</strong> utility model is based on meter<strong>in</strong>g usage,<br />

or a pay as you go approach. Unlike subscriber<br />

services, metered services are based on actual<br />

usage rates<br />

Table 7: Rappa’s (Rappa 2001) classification scheme<br />

Applegate (Applegate 2001) identifies four categories for digital bus<strong>in</strong>ess models, for which she gives<br />

a number of examples (see Table 8).<br />

29

Knowledge of the Problem Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Category<br />

Focused Distributor <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Portal <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Producer <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

Infrastructure Provider <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong>s<br />

3.1.3 <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Components<br />

Retailer, Marketplace, Aggregator, Infomediary, Exchange<br />

Horizontal Portals, Vertical Portals, Aff<strong>in</strong>ity Portals<br />

Manufacturer, Service Provider, Educator, Advisor, Information<br />

and news services, Custom Supplier<br />

Infrastructure portals<br />

Table 8: Applegate’s taxonomy of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models<br />

While def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what bus<strong>in</strong>ess models actually are has brought some order <strong>in</strong>to the confusion, many<br />

authors have gone further to def<strong>in</strong>e of what elements bus<strong>in</strong>ess models are composed of. This is the<br />

first step to mak<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess models a tool for bus<strong>in</strong>ess plann<strong>in</strong>g that help managers understand and<br />

describe the bus<strong>in</strong>ess logic of their firm. In this section I outl<strong>in</strong>e these attempts to def<strong>in</strong>e the bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

components, also referred to as “elements”, “build<strong>in</strong>g blocks”, “functions” or “attributes” of bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models. I classify this literature among two ma<strong>in</strong> aspects, which are, on the one hand product, bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

actor- and network-centric literature and on the other hand market<strong>in</strong>g-centric literature. <strong>The</strong> authors of<br />

the second category most often cover both aspects mentioned above.<br />

However, it must be said that the different approaches and bus<strong>in</strong>ess model component descriptions<br />

vary greatly regard<strong>in</strong>g their depth and rigor, rang<strong>in</strong>g from simple enumerations to detailed<br />

descriptions. Some of these concepts are highly abstract and very precise and some are merely lists of<br />

relatively low conceptual contribution. In this section I simply list and describe the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model<br />

elements of the authors that mention bus<strong>in</strong>ess model components. It is only <strong>in</strong> section 3.1.5 that I will<br />

dig deeper <strong>in</strong>to some of the more formal model<strong>in</strong>g approaches.<br />

3.1.3.1 Product-, Actor- and Network-Centric <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Frameworks<br />

Mahadevan (2000) <strong>in</strong>dicates that a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model consists of a configuration of three streams that are<br />

critical to the bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Firstly, the value stream, which identifies the value <strong>proposition</strong> for the bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

partners and the buyers. Secondly, the revenue stream, which is a plan for assur<strong>in</strong>g revenue generation<br />

for the bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Thirdly, the logistical stream, which addresses various issues related to the <strong>design</strong> of<br />

the supply cha<strong>in</strong> for the bus<strong>in</strong>ess.<br />

Afuah and Tucci (2003) <strong>in</strong> contrast expla<strong>in</strong> that a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model should <strong>in</strong>clude answers to a number<br />

of questions: What value to offer customers, which customers to provide the value to, how to price the<br />

value, who to charge for it, what strategies to undertake <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g the value, how to provide that<br />

value, and how to susta<strong>in</strong> any advantage from provid<strong>in</strong>g the value. <strong>The</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess model approach they<br />

outl<strong>in</strong>e is value-centered and takes <strong>in</strong> account the creation of value through several actors. In their<br />

conception of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model one can f<strong>in</strong>d a list of bus<strong>in</strong>ess model components presented <strong>in</strong> Table 9.<br />

Component<br />

Customer Value<br />

Scope<br />

Pric<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Revenue Source<br />

Connected Activities<br />

Questions for all bus<strong>in</strong>ess models<br />

<strong>The</strong> firm must ask itself if it is offer<strong>in</strong>g its customers someth<strong>in</strong>g dist<strong>in</strong>ctive or at<br />

a lower cost than its competitors<br />

A company must def<strong>in</strong>e to what customers it is offer<strong>in</strong>g value and what range of<br />

products and services embody this value<br />

Pric<strong>in</strong>g is about how a firm prices the value it offers<br />

A firm must ask itself where the <strong>in</strong>come comes from and who will pay for what<br />

value and when. It must also def<strong>in</strong>e marg<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> each market and f<strong>in</strong>d out what<br />

drives them.<br />

<strong>The</strong> connected activities lay out what set of activities the firm has to perform to<br />

offer its value and when. It expla<strong>in</strong>s how activities are connected.<br />

30

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

Implementation<br />

Capabilities<br />

Susta<strong>in</strong>ability<br />

A company has to ask itself what organizational structure, systems, people, and<br />

environment suit the connected activities best. It must def<strong>in</strong>e the fit between<br />

them.<br />

A firm has to f<strong>in</strong>d out what its capabilities are and which capability gaps it has<br />

to fill. It should ask itself if there is someth<strong>in</strong>g dist<strong>in</strong>ctive about these<br />

capabilities that allow the firm to offer the value better than other firms and that<br />

makes them difficult to imitate.<br />

A company should understand what it is about the firm that makes it difficult for<br />

other firms to imitate. It must def<strong>in</strong>e how it can keep mak<strong>in</strong>g money and susta<strong>in</strong><br />

a competitive advantage.<br />

Table 9: Afuah and Tucci’s elements of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model (2003)<br />

In l<strong>in</strong>e with Timmers’ bus<strong>in</strong>ess mode description above (1998), Stähler (2001; 2002) has a networkcentric<br />

approach to bus<strong>in</strong>ess models and also excludes the market<strong>in</strong>g model from his bus<strong>in</strong>ess model<br />

framework. For him a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model consists of four components as summarized <strong>in</strong> Table 10. Firstly,<br />

a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model conta<strong>in</strong>s a description of what value a customer or partner (e.g. a supplier) receives<br />

from the bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Stähler calls this the value <strong>proposition</strong>. It answers the question of what value the<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess creates for its stakeholders. Secondly, he <strong>in</strong>troduces a l<strong>in</strong>k between the firm and the customer,<br />

which is the product. Thus, a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model conta<strong>in</strong>s a description of the product or services the firm<br />

is provid<strong>in</strong>g the market. It answers the question of what the firm sells. Thirdly, a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>s the description of the architecture of value creation. <strong>The</strong> value architecture del<strong>in</strong>eates the<br />

value cha<strong>in</strong>, the economic agents that participate <strong>in</strong> the value creation and their roles. <strong>The</strong> value<br />

architecture answers the question of how the value is created and <strong>in</strong> what configuration. F<strong>in</strong>ally, a<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess model describes the basis and the sources of <strong>in</strong>come for the firm. <strong>The</strong> value and the<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>ability of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess are be<strong>in</strong>g determ<strong>in</strong>ed by its revenue model. This component answers the<br />

question of how a company earns money.<br />

BM component<br />

Value Proposition<br />

Product/Services<br />

Architecture<br />

Revenue <strong>Model</strong><br />

Questions to ask<br />

What value does the company create for customers and partners?<br />

What does the firm sell?<br />

How and through what configuration is value created?<br />

How does the company earn money?<br />

Table 10: Stähler’s bus<strong>in</strong>ess model components (based on (Stähler 2001; Stähler 2002)<br />

Similar to Stähler (2001) and also based on Timmers (1998), Papakiriakopoulos and Poulymenakou<br />

(2001) propose a network-centric bus<strong>in</strong>ess model framework that focuses on actors and relationships.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir model consists of four ma<strong>in</strong> components, namely coord<strong>in</strong>ation issues, collective competition,<br />

customer value and core competences. <strong>The</strong> first component aims at def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the management of<br />

dependencies among activities. For example the shar<strong>in</strong>g of an <strong>in</strong>formation resource among several<br />

actors requires coord<strong>in</strong>ation mechanisms that affect the structure of the organization. <strong>The</strong> second<br />

component, collective competition, describes the relationship to other companies, which can be<br />

competitive, co-operator, or both at the same time. This construct resembles the concept of coopetition<br />

described by Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996). <strong>The</strong> third component, customer value,<br />

aligns the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model with the market and customer needs. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the core competencies def<strong>in</strong>e<br />

how a firm exploits its resources fac<strong>in</strong>g the opportunities of the market.<br />

Maitland and Van de Kar (2002) apply a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model concept to a number of case studies <strong>in</strong> the<br />

mobile <strong>in</strong>formation and enterta<strong>in</strong>ment services. <strong>The</strong>y describe the value <strong>proposition</strong>, the market<br />

segment, the companies <strong>in</strong>volved and the revenue model of different <strong>in</strong>novative companies <strong>in</strong> the<br />

mobile telecommunications service <strong>in</strong>dustry.<br />

Chesbrough and Rosenbloom (2000) simply list six ma<strong>in</strong> functions of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. <strong>The</strong>se are the<br />

31

Knowledge of the Problem Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

articulation of the value <strong>proposition</strong>, the identification of the market segment, the def<strong>in</strong>ition of the<br />

structure of the value cha<strong>in</strong> with<strong>in</strong> the firm, the def<strong>in</strong>ition of the cost structure and profit potential, the<br />

description of the position of the firm with<strong>in</strong> the value network, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g identification of<br />

complementors and competitors and f<strong>in</strong>ally the formulation of the competitive strategy.<br />

Unlike most other authors on bus<strong>in</strong>ess model components Alt and Zimmermann (2001) <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

elements such as mission, processes, legal issues and technology <strong>in</strong>to their framework. <strong>The</strong> six generic<br />

elements they mention are outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Table 11.<br />

BM element<br />

Mission<br />

Structure<br />

Processes<br />

Revenues<br />

Legal issues<br />

Technology<br />

description<br />

A critical part of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is develop<strong>in</strong>g a high-level understand<strong>in</strong>g of the<br />

overall vision, strategic goals and the value <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the basic product or<br />

service features.<br />

Structure determ<strong>in</strong>es the roles of the different agents <strong>in</strong>volved and the focus on<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustry, customers and products.<br />

Processes provide a more detailed view on the mission and the structure of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

model. It shows the elements of the value creation process.<br />

Revenues are the "bottom l<strong>in</strong>e" of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model.<br />

Legal issues <strong>in</strong>fluence all aspects of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model and the general vision<br />

Technology is an enabler and a constra<strong>in</strong>t for IT-based bus<strong>in</strong>ess models. Also,<br />

technological change has an impact on the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model <strong>design</strong>.<br />

Table 11: Alt and Zimmermann's (2001) bus<strong>in</strong>ess model elements<br />

3.1.3.2 Market<strong>in</strong>g-Specific Frameworks<br />

Authors presented <strong>in</strong> this section <strong>in</strong>clude market<strong>in</strong>g specific issues <strong>in</strong>to their bus<strong>in</strong>ess model<br />

frameworks. A very <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess model <strong>proposition</strong> has been developed by Hamel (2000). For<br />

him a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is simply a bus<strong>in</strong>ess concept that has been put <strong>in</strong>to practice, but for which he<br />

develops a number of elements. He identifies four ma<strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess model components that range from<br />

core strategy, strategic resources over value network to customer <strong>in</strong>terface. <strong>The</strong>se components are<br />

related to each other through three “bridges” and are decomposed <strong>in</strong>to different sub-elements. <strong>The</strong><br />

ma<strong>in</strong> contribution of this concept illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 16 and Table 12 is a view of the overall picture<br />

of a firm.<br />

CUSTOMER BENEFITS CONFIGURATION COMPANY BOUNDARIES<br />

CUSTOMER<br />

INTERFACE<br />

CORE<br />

STRATEGY<br />

STRATEGIC<br />

RESOURCES<br />

VALUE<br />

NETWORK<br />

Fulfillment & Support<br />

Information & Insight<br />

Relationship Dynamics<br />

Pric<strong>in</strong>g Structure<br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> Mission<br />

Product/Market Scope<br />

Basis for Differentiation<br />

Core Competencies<br />

Strategic Assets<br />

Core Processes<br />

Suppliers<br />

Partners<br />

Coalitions<br />

EFFICIENT / UNIQUE / FIT / PROFIT BOOSTERS<br />

Figure 16: Hamel’s (2000) bus<strong>in</strong>ess model concept<br />

32

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

Elements<br />

Connections<br />

Name<br />

Core Strategy<br />

Strategic<br />

Resources<br />

Customer<br />

Interface<br />

Value<br />

Network<br />

Configuration<br />

Customer<br />

Benefits<br />

Company<br />

Boundaries<br />

Description<br />

This element def<strong>in</strong>es the overall bus<strong>in</strong>ess mission, which captures what the<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is <strong>design</strong>ed to accomplish. Further, it def<strong>in</strong>es the product and<br />

market scope and specifies <strong>in</strong> what segments the company competes. F<strong>in</strong>ally, it<br />

outl<strong>in</strong>es how the firm competes differently than its competitors.<br />

This element conta<strong>in</strong>s the core competencies of a firm. In other words, what a firm<br />

knows, its skills and unique capabilities. <strong>The</strong>n it specifies the strategic assets, such<br />

as <strong>in</strong>frastructure, brands and patents. Last, this element outl<strong>in</strong>es the core processes<br />

of the firm; it expla<strong>in</strong>s what people actually do.<br />

This element is composed of fulfillment and support, which refers to the way the<br />

firm goes to market and reaches its customers (e.g. channels). Second, <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

and <strong>in</strong>sight def<strong>in</strong>es all the knowledge that is collected from and used on behalf of<br />

the customer. Third, the relationship dynamics refer to the nature of the <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

between the producer and the customer. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the pric<strong>in</strong>g structure expla<strong>in</strong>s what<br />

you charge the customer for and how you do this.<br />

<strong>The</strong> value network outl<strong>in</strong>es the network that surrounds the firm and complements<br />

and amplifies the firm’s resources. It is composed of suppliers, partners and<br />

coalitions. Partners typically supply critical complements to a f<strong>in</strong>al product or<br />

solution, whereas coalitions represent alliances with like-m<strong>in</strong>ded competitors.<br />

This connection refers to the unique way <strong>in</strong> which competencies, assets, and<br />

processes are comb<strong>in</strong>ed and <strong>in</strong>terrelated <strong>in</strong> support of a particular strategy.<br />

This l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>in</strong>termediates between the core strategy and the customer <strong>in</strong>terface. It<br />

def<strong>in</strong>es the particular bundle of benefits that is actually be<strong>in</strong>g offered to the<br />

customer.<br />

This bridge refers to the decisions that have been made about what the firm does<br />

and what it contracts out the value network.<br />

Table 12: Hamel’s (2000) bus<strong>in</strong>ess model components<br />

Like Hamel (2000), L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell (2000) propose a comprehensive approach to bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models. Further, they stress the fact that many people speak of bus<strong>in</strong>ess models when they actually<br />

only mean a specific component of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. <strong>The</strong>y list the follow<strong>in</strong>g components: the pric<strong>in</strong>g<br />

model, the revenue model, the channel model, the commerce process model, the Internet-enabled<br />

commerce relationship, the organizational form and the value <strong>proposition</strong> (see Figure 17).<br />

33

Knowledge of the Problem Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

Why are we one organization?<br />

How do we get and keep customers?<br />

What’s our dist<strong>in</strong>ctive value <strong>proposition</strong> to each constituency?<br />

Who are our<br />

customers<br />

and what are<br />

their needs?<br />

What do we<br />

offer them?<br />

• Products<br />

• Services<br />

• Experiences<br />

How do we<br />

reach them?<br />

How do we<br />

price?<br />

How do we deliver<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ctively?<br />

How do we<br />

execute?<br />

What are<br />

our<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ctive<br />

capabilities?<br />

How is our<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

structure<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ctive?<br />

Dist<strong>in</strong>ctive Revenue Implications<br />

Dist<strong>in</strong>ctive Cost Implications<br />

Dist.<br />

Return<br />

Dist<strong>in</strong>ctive Asset Implications<br />

Figure 17: L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell’s (2000) bus<strong>in</strong>ess model concept<br />

Weill and Vitale (2001) have a slightly different approach, they give a systematic and practical<br />

analysis of eight so called atomic e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess models as describe <strong>in</strong> Table 6. <strong>The</strong>se atomic bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models can be comb<strong>in</strong>ed to form an e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>itiative. Every one of these atomic e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess models<br />

is analyzed accord<strong>in</strong>g to its strategic objectives and value <strong>proposition</strong>, its sources of revenue, its<br />

critical success factors and its core competencies. In addition the authors also outl<strong>in</strong>e the elements to<br />

analyze an e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>itiative which are a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model’s channels, customer segments and IT-<br />

Infrastructure.<br />

BM Element<br />

Description<br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> model summary<br />

Strategic Objective<br />

and Value<br />

Proposition<br />

Gives an overall view of the target customer, the product and service<br />

offer<strong>in</strong>g and the unique and valuable position targeted by the firm. It<br />

def<strong>in</strong>es what choices and trad-offs the firm will make.<br />

Sources of Revenue A realistic view of the sources of revenue is a fundamental question for e-<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess models.<br />

Critical Success<br />

Factors<br />

Core Competencies<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are th<strong>in</strong>gs a firm must do well to flourish. <strong>The</strong>re are a set of general<br />

critical success factors for every atomic bus<strong>in</strong>ess model.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are the competencies necessary that should be created, nurtured,<br />

and developed <strong>in</strong>-house and contribute to the power of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model.<br />

Elements of an e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiative<br />

Customer Segments<br />

Channels<br />

IT Infrastructre<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Weill and Vitale an e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>itiative should always start<br />

with the customer. This means understand<strong>in</strong>g which customer segments<br />

are targeted and what the value <strong>proposition</strong> is for each segment.<br />

A channel is the conduit by which a firm's products or services are offered<br />

or distributed to the customer. Reach<strong>in</strong>g target customer segments<br />

requires careful channel selection and management. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly the<br />

authors add that <strong>in</strong> e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess the channel should be considered a feature<br />

of the product offer and thus part of the value <strong>proposition</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> IT <strong>in</strong>frastructure is used <strong>in</strong> to connect the different parts of the firm<br />

and l<strong>in</strong>k to suppliers, customers, and allies.<br />

Table 13: Weill and Vitale's bus<strong>in</strong>ess model and e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>itiative elements (2001)<br />

<strong>The</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess model approach by Petrovic, Kittl et al. (Petrovic, Kittl et al. 2001) suggests that a<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess model can be divided <strong>in</strong>to seven sub-models, which are the value model, the resource model,<br />

the production model, the customer relations model, the revenue model, the capital model and the<br />

34

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

market model. <strong>The</strong>se sub-models and their <strong>in</strong>terrelation shall describe the logic of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess system<br />

for creat<strong>in</strong>g value that lies beh<strong>in</strong>d the actual processes. <strong>The</strong> value model describes the logic of what<br />

core products, services and experiences are delivered to the customer and other value-added services<br />

derived from the core competence. <strong>The</strong> revenue model describes the logic of how elements are<br />

necessary for the transformation process, and how to identify and procure the required quantities. <strong>The</strong><br />

production model describes the logic of how elements are comb<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the transformation process<br />

from the source to the output. <strong>The</strong> customer relations model scribes the logic of how to reach, serve,<br />

and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> customers. It consists of the follow<strong>in</strong>g sub-models: a distribution model – the logic<br />

beh<strong>in</strong>d the delivery processes, a market<strong>in</strong>g model – the logic beh<strong>in</strong>d reach<strong>in</strong>g and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

customers and a service model – the logic beh<strong>in</strong>d serv<strong>in</strong>g the customer. <strong>The</strong> revenue model describes<br />

the logic of what, when, why, and how the company receives compensation <strong>in</strong> return for the products.<br />

<strong>The</strong> capital model describes the logic of how f<strong>in</strong>ancial sourc<strong>in</strong>g occurs to create a debt and equity<br />

structure, and how that money is utilised with respect to assets and liabilities over time. <strong>The</strong> market<br />

model describes the logic of choos<strong>in</strong>g a relevant environment <strong>in</strong> which the bus<strong>in</strong>ess operates.<br />

Compared to the previous authors Magretta (2002) has a very simple and pragmatic view on bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

models. She dist<strong>in</strong>guishes between two elementary parts of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. On the one hand the<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess activities associated with mak<strong>in</strong>g someth<strong>in</strong>g (e.g. <strong>design</strong>, procurement, and manufactur<strong>in</strong>g)<br />

and on the other hand the bus<strong>in</strong>ess activities associated with sell<strong>in</strong>g someth<strong>in</strong>g (e.g. customer<br />

identification, sell<strong>in</strong>g, transaction handl<strong>in</strong>g, distribution and delivery).<br />

3.1.4 Representation Tools<br />

In addition to outl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the components of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model, some authors offer a set of bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

model representation tools. Weill and Vitale (2001) have developed a formalism to assist analyz<strong>in</strong>g e-<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>itiatives, which they call e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess model schematic. <strong>The</strong> schematic is a pictorial<br />

representation, aim<strong>in</strong>g to high-light a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model's important elements. This <strong>in</strong>cludes the firm of<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest, its suppliers and allies, the major flows of product, <strong>in</strong>formation and money and f<strong>in</strong>ally the<br />

revenues and other benefits each participant receives. By us<strong>in</strong>g such a representation the authors<br />

<strong>in</strong>tend to uncover major contradictions of a bus<strong>in</strong>ess model, highlight the core competencies to<br />

implement the model, show the position of each player <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dustry value cha<strong>in</strong>, deduce the<br />

organizational form and IT <strong>in</strong>frastructure for implementation and reveal which entity owns the<br />

customer relationship, data, and transaction.<br />

Service<br />

Provider<br />

Customer<br />

Firm of Interest<br />

Supplier<br />

Customer<br />

Ally<br />

$<br />

0<br />

i<br />

Electronic Relationship<br />

Primary Relationship<br />

Flow of Money<br />

Flow of Product<br />

Flow of Information<br />

Figure 18: bus<strong>in</strong>ess model schematic of the direct to customer model and (Weill and Vitale 2001)<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>design</strong> approach of Gordijn (2002), which among other th<strong>in</strong>gs aims at visualiz<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess models<br />

is outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g section.<br />

3.1.5 Ontological <strong>Model</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Whereas the bus<strong>in</strong>ess model frameworks presented until here stay relatively <strong>in</strong>formal and descriptive<br />

this section treats of ontology-style models. Under ontological modell<strong>in</strong>g I understand a rigorous<br />

approach to def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess models. In other terms this means carefully and precisely def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess model terms, concepts, components and their relationships. From the authors analyzed <strong>in</strong> this<br />

literature review Gordijn (2002) provides the most rigorous conceptual model<strong>in</strong>g approach, which he<br />

35

Knowledge of the Problem Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

calls e 3 -value. This methodology is based on a generic value-oriented ontology specify<strong>in</strong>g what's <strong>in</strong><br />

an e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. On the one hand it has the goal of improv<strong>in</strong>g communication and decision<br />

mak<strong>in</strong>g related to e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess and on the other hand it aims at enhanc<strong>in</strong>g and sharpen<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess operations and requirements through scenario analysis and quantification<br />

(cf. 3.1.5). e 3 -value consists of a number of generic concepts and relationships illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 19.<br />

Gordijn specifies actors that produce, distribute or consume objects of value by perform<strong>in</strong>g value<br />

activities. <strong>The</strong> objects of value are exchanged via value <strong>in</strong>terfaces of actors or activities. Value<br />

<strong>in</strong>terfaces have value ports offer<strong>in</strong>g or request<strong>in</strong>g objects of value. <strong>The</strong> trade of value objects is<br />

represented by value exchanges, which <strong>in</strong>terconnect value ports of actors or value <strong>in</strong>terfaces.<br />

Actor<br />

assigned to<br />

Value with similar<br />

0..1 1..n Interface 1..n 0..1<br />

1 1..n<br />

1<br />

Market<br />

Segment<br />

Value<br />

Offer<strong>in</strong>g<br />

performed by<br />

has<br />

assigned to<br />

0..n<br />

0..1<br />

Value<br />

Activity<br />

1..n<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>s<br />

1..n<br />

Value<br />

Exchange<br />

between<br />

0..n<br />

2<br />

1..n<br />

Value<br />

Port<br />

offers/request<br />

0..n 1<br />

Value<br />

Object<br />

Figure 19: e 3 -value ontology for e-bus<strong>in</strong>ess (Gordijn, Akkermans et al. 2001)<br />

<strong>The</strong> e 3 -value methodology has been applied to a real world bus<strong>in</strong>ess case and evaluated one-year-anda-half<br />

later (Gordijn and Akkermans 2003). Lessons learned <strong>in</strong>clude that the method is lack<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

market<strong>in</strong>g perspective, that bus<strong>in</strong>ess units should be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the analysis and that it would be<br />

helpful to work with evolutionary scenarios. However, Gordijn and Akkermans are positive about<br />

their methodology enhanc<strong>in</strong>g the common understand<strong>in</strong>g of bus<strong>in</strong>ess ideas, which was not possible by<br />

traditional e.g. verbal ways. Furthermore, they believe that a model-based approach to bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

problems can help asses the consequences of changes <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess models.<br />

3.1.6 <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong>s and Change<br />

Because models are static by nature and simply take a snapshot of a current situation, a number of<br />

authors add a time trajectory to bus<strong>in</strong>ess models and <strong>in</strong>troduce the concept of change. This allows<br />

them to go from a current state or bus<strong>in</strong>ess model to a desired state or new bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. L<strong>in</strong>der and<br />

Cantrell (2000), for example, mention that bus<strong>in</strong>ess models are a picture at a po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> time, but that<br />

most firm’s bus<strong>in</strong>ess models are under constant pressure to change because of numerous pressures <strong>in</strong><br />

the firm’s environment (e.g. technology, law and competition)(cf. also 2.3). <strong>The</strong>refore and <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

coord<strong>in</strong>ate and channel change <strong>in</strong>side a company they <strong>in</strong>troduce so-called change models. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>guish four basic types accord<strong>in</strong>g to their degree to which they change the core logic of a<br />

company, namely realization models, renewal models, extension models and journey models (see<br />

Figure 20). <strong>The</strong> realization model focuses on small changes <strong>in</strong> the exist<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess model of a firm <strong>in</strong><br />

order to maximize its potential. It often <strong>in</strong>volves preoccupations, such as brand ma<strong>in</strong>tenance, product<br />

l<strong>in</strong>e extensions, geographic expansions or additional sales channels. Renewal models are characterized<br />

by consistent revitalization of product and service platforms, brands, cost structures and technology<br />

bases. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell a renew<strong>in</strong>g firm leverages its core skills to create new<br />

positions on the price/value curve. This k<strong>in</strong>d of change model also often <strong>in</strong>volves attack<strong>in</strong>g untouched<br />

markets and <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g new retail<strong>in</strong>g formats. Extension models expand bus<strong>in</strong>esses to cover new<br />

ground. An extend<strong>in</strong>g company stretches its operat<strong>in</strong>g model to <strong>in</strong>clude new markets, value cha<strong>in</strong><br />

functions, and product and service l<strong>in</strong>es. This k<strong>in</strong>d of model often <strong>in</strong>volves forward, backward and<br />

36

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>Ontology</strong> - a <strong>proposition</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>design</strong> science approach<br />

horizontal <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong> the value cha<strong>in</strong>. F<strong>in</strong>ally, journey models provoke most change and take a<br />

company to a complete new bus<strong>in</strong>ess model.<br />

Journey model<br />

Extension model<br />

Renewal model<br />

Realization model<br />

No bus<strong>in</strong>ess model<br />

change<br />

<strong>Bus<strong>in</strong>ess</strong> model<br />

change<br />

Degree to which<br />

core logic<br />

changes<br />

Figure 20: Change <strong>Model</strong>s (L<strong>in</strong>der and Cantrell 2000)<br />

Tapscott, Ticoll et al. (2000) propose a change methodology <strong>in</strong> six steps towards creat<strong>in</strong>g a b-web<br />

company (cf. Figure 15 and Table 4). <strong>The</strong> first step consists of describ<strong>in</strong>g the current value <strong>proposition</strong><br />

by def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g end-customers, offer<strong>in</strong>gs, customer value and the value <strong>proposition</strong>’s strengths and<br />

weaknesses from a customer’s perspective. <strong>The</strong> second step consists of disaggregat<strong>in</strong>g and identify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the entities that contribute to the total value-creation system. <strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g step envisions b-web<br />

enable value. In other words, planners must step outside their day-to-day mental models to develop<br />

creative and discont<strong>in</strong>uous views of do<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess. This means ask<strong>in</strong>g what new bus<strong>in</strong>ess models –<br />

ways of creat<strong>in</strong>g, sett<strong>in</strong>g, and deliver<strong>in</strong>g value and facilitat<strong>in</strong>g relationships with customers, suppliers,<br />

and partners – could be envisaged. In the fourth step the company must reaggregate. This step entails<br />

repopulat<strong>in</strong>g the categories of value contributors and assign<strong>in</strong>g contributions to the various classes of<br />

participants. <strong>The</strong> fifth step consists of prepar<strong>in</strong>g a value map, which is a graphical depiction of how a<br />

b-web operates. It identifies the participants, such as strategic partners, suppliers and customers and<br />

their exchanges of value. <strong>The</strong> last step consists of do<strong>in</strong>g the b-web mix, which means consider<strong>in</strong>g how<br />

each type and subtype might enhance customer value, provide competitive differentiation and<br />

advantage and reduce costs for the participants.<br />

In his e 3 -value methodology Gordijn (2002) outl<strong>in</strong>es a change methodology based on value model<br />

deconstruction and reconstruction, which is ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>spired by Tapscott, Ticoll et al. (2000) Evans<br />

and Wurster (2000) and Timmers (1999). He splits the process <strong>in</strong>to two questions, namely, which<br />

value add<strong>in</strong>g activities exist, and which actors are will<strong>in</strong>g to perform these activities.<br />

Petrovic, Kittl et al. (2001) specify that the improvement and change of a real world bus<strong>in</strong>ess model is<br />

related to the ability to change a manager’s mental model. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to them, people often talk about<br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g time and costs via automat<strong>in</strong>g or re<strong>design</strong><strong>in</strong>g processes when really they want to improve<br />

their bus<strong>in</strong>ess model. To change this Petrovic, Kittl et al. <strong>in</strong>troduce double-loop learn<strong>in</strong>g to explicit<br />

mental models through a systemic bus<strong>in</strong>ess model concept <strong>in</strong> order to provide a holistic, broad, longterm<br />

and dynamic view to help re<strong>design</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess models.<br />