NO 73 MERRION SQUARE, DUBLIN 2 - Irish Traditional Music Archive

NO 73 MERRION SQUARE, DUBLIN 2 - Irish Traditional Music Archive

NO 73 MERRION SQUARE, DUBLIN 2 - Irish Traditional Music Archive

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>NO</strong> <strong>73</strong> <strong>MERRION</strong> <strong>SQUARE</strong>, <strong>DUBLIN</strong> 2<br />

The Premises of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong><br />

The <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> has its home in a fine 18th-century<br />

terraced building, more than 200 years old, which is situated in a<br />

historic quarter of Georgian Dublin. No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square is a fourstorey<br />

townhouse of three bays over a basement and area, with a threestorey<br />

return and a mews stable house, and external vaulted cellars. It<br />

is owned by the State through the Office of Public Works (OPW).<br />

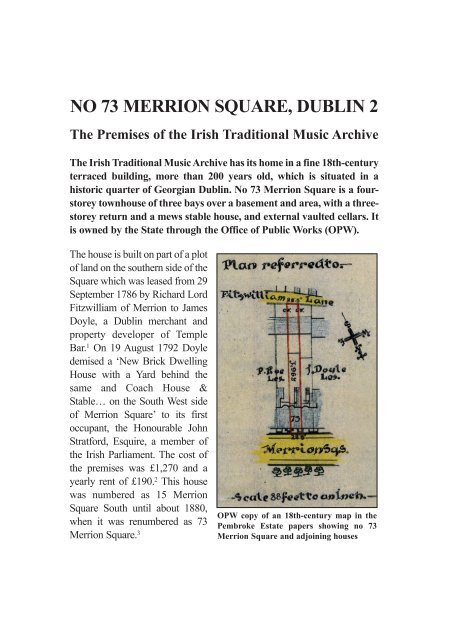

The house is built on part of a plot<br />

of land on the southern side of the<br />

Square which was leased from 29<br />

September 1786 by Richard Lord<br />

Fitzwilliam of Merrion to James<br />

Doyle, a Dublin merchant and<br />

property developer of Temple<br />

Bar. 1 On 19 August 1792 Doyle<br />

demised a ‘New Brick Dwelling<br />

House with a Yard behind the<br />

same and Coach House &<br />

Stable… on the South West side<br />

of Merrion Square’ to its first<br />

occupant, the Honourable John<br />

Stratford, Esquire, a member of<br />

the <strong>Irish</strong> Parliament. The cost of<br />

the premises was £1,270 and a<br />

yearly rent of £190. 2 This house<br />

was numbered as 15 Merrion<br />

Square South until about 1880,<br />

when it was renumbered as <strong>73</strong><br />

Merrion Square. 3<br />

OPW copy of an 18th-century map in the<br />

Pembroke Estate papers showing no <strong>73</strong><br />

Merrion Square and adjoining houses

2<br />

No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square, Dublin 2<br />

Merrion Square, Dublin’s best known Georgian square, is itself built<br />

on part of the Fitzwilliam Estate, lands lying between the old coast<br />

road to Blackrock (now Fenian Street, Grand Canal Street, etc.) and<br />

the old road to Donnybrook (now Leeson Street, etc.), and leased by<br />

the Fitzwilliam family from Dublin Corporation since medieval<br />

times. 4 From the early eighteenth century, fashionable development<br />

was taking place on lands to the south-east of the city. This<br />

development reached a significant stage in 1745 with the building of<br />

Kildare House (now Leinster House) on its eastern margin by the<br />

Earl of Kildare (later the Duke of Leinster). The lawn of Leinster<br />

House, with the National Gallery of Ireland and some houses of the<br />

later eighteenth century, now forms the west side of Merrion Square.<br />

By 1762 the Fitzwilliam Estate had begun the development of the<br />

Square and laid it out in building plots, and by the early 1770s<br />

Merrion Square North and part of Merrion Square East had been<br />

built as an aristocratic residential area. From the 1770s through the<br />

1790s the remainder of Merrion Square East and Merrion Square<br />

South was similarly developed, piecemeal, and by 1800 the Square<br />

was substantially completed. 5<br />

In their initial decades the houses on Merrion Square were great<br />

townhouses for people who had, for the most part, country estates<br />

elsewhere. The houses were built in brick, with stone variously used,<br />

to the highest standards of their time. Typical architectural features<br />

are classical door columns with fanlights and sidelights, well<br />

proportioned large windows, and ironwork balconies or window<br />

guards. On the later south side of the Square, the houses are less<br />

individualised and less grand. The decorative classical plasterwork<br />

of their entrances and main rooms is in low relief, and is reinforced<br />

by ornamental joinery. The southern houses have bowed rear walls.

The Premises of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> 3<br />

The history of the houses on Merrion Square mirrors the elite social<br />

and economic history of Dublin and Ireland during most of their two<br />

hundred and more years. Built by speculative developers and<br />

wealthy tradesmen, they were at first the townhouses of the nobility<br />

and gentry of the Ascendancy (including members of the <strong>Irish</strong><br />

Parliament), of the upper clergy of the Established Church, of the<br />

judiciary, and of lawyers prominent in government. Their earliest<br />

owners may have felt them to be rather cramped by comparison with<br />

their country houses and estates, with servants in unwelcome<br />

proximity. The houses were occupied most intensively during the<br />

parliamentary and theatrical seasons, and reached their apogee<br />

during the period of ‘Grattan’s Parliament’, from 1782 to the end of<br />

the century, when the <strong>Irish</strong> Parliament had achieved legislative<br />

independence from London.<br />

After the passing of the Act of Union in 1800 and the political<br />

decline of Dublin, the houses increasingly became the dwellings of<br />

prominent barristers and medical men, and also sometimes their<br />

consulting rooms, and the religious complexion of the Square began<br />

to change from Protestant to Catholic. Following the 19th- and 20thcentury<br />

drift of the wealthy to the suburbs, and the foundation of the<br />

<strong>Irish</strong> Free State with its legislature in Leinster House in 1922, the<br />

buildings were often divided into business offices (especially for<br />

solicitors, doctors and dentists) and flats, and many were acquired by<br />

the State to house Government departments. During WW2 air-raid<br />

shelters were built in the gardens of houses on the Square, no <strong>73</strong><br />

among them.<br />

In recent decades, with the transfer of Government departments to<br />

purpose-built office blocks, the Merrion Square houses have<br />

increasingly provided accommodation for national organisations and<br />

cultural and educational bodies, in the lee of the Natural History<br />

Museum and the National Gallery of Ireland. These organisations currently<br />

include Foras na Gaeilge, the Dublin Institute of Advanced<br />

Studies, the <strong>Irish</strong> Red Cross Society, the Royal Institute of the<br />

Architects of Ireland, the Goethe-Institut, the <strong>Irish</strong> Architectural<br />

<strong>Archive</strong>, the <strong>Irish</strong> Manuscripts Commission, the Royal Society of<br />

Antiquaries of Ireland, the Arts Council/ An Chomhairle Ealaíon, the<br />

Central Catholic Library, the Georgian Society, the American College<br />

Dublin of Lynn University, the National University of Ireland, the<br />

Keough Naughton Centre of the University of Notre Dame – and the<br />

<strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong>/ Taisce Cheol Dúchais Éireann.

The Earl of Aldborough’s Minuet<br />

Da Capo<br />

The Countess of Aldborough’s Minuet<br />

composed by the E— of A—b—h<br />

3<br />

Two undated but c. 1800 minuets published by both E. Rhames and Hime of Dublin.<br />

It is not known which Earl of Aldborough is in question, but it was likely John<br />

Stratford’s brother Edward, the 2nd Earl.<br />

Belan House, Co Kildare, a home of the Stratford family, to which John Stratford<br />

moved from no <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square on becoming the 3rd Earl of Aldborough

The Premises of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> 5<br />

OCCUPANTS Of <strong>NO</strong> <strong>73</strong> <strong>MERRION</strong> <strong>SQUARE</strong><br />

1792–1801 Honourable John Stratford, Stratford Lodge,<br />

Baltinglass, Co Wicklow 6<br />

Stratford (c. 1742–1823), one of fourteen children,<br />

belonged to a prominent Wicklow family of English<br />

settlers of the Cromwellian period. 7 He was a member<br />

of the <strong>Irish</strong> Parliament for Baltinglass (1763–76), for<br />

Wicklow (1776–90), and again for Baltinglass<br />

(1790–1800), and a governor of Co Wicklow in 1795.<br />

Regarded as a moderate, he voted against Catholic<br />

relief and for the Act of Union. 8 In 1801, on the death<br />

of his eccentric brother who had succeeded his father<br />

the 1st Earl, he became 3rd Earl of Aldborough of<br />

Upper Ormond; 3rd Viscount Aldborough of Belan,<br />

Co Kildare; 3rd Baron of Baltinglass, Co Wicklow;<br />

and 3rd Viscount Amiens. He lived subsequently at<br />

Belan. 9 His wife Elizabeth Hamilton, daughter of the<br />

Archdeacon of Raphoe, had a certain notoriety; she<br />

was also accounted the best horsewoman in Ireland. 10<br />

1801–1824 Right Honourable Lodge Evans Morres (from<br />

1815 Lodge Evans de Montmorency), Baron<br />

Frankfort, Maryville, Finglas, Co Dublin 11<br />

Morres (1747–1822), admitted to the <strong>Irish</strong> Bar in<br />

1769, was a member of the <strong>Irish</strong> Parliament for<br />

Innistoge (1768–70), for Bandon Bridge (1776–96),<br />

for Ennis (1796–97) and Dingle (1798–1800). Highly<br />

ambitious, he beseiged Dublin Castle for advancement<br />

and was regarded by an official there as an<br />

‘importunate savage’. 12 He was Chief Secretary to the<br />

Lord Lieutenant for 1795–1800, and was appointed to<br />

the Treasury Board in 1796. 13 In 1800, having voted<br />

for the Union, he was created 1st Baron Frankfort of<br />

Galway, Co Kilkenny. He also lived at Green Street,<br />

Grosvenor Square, London. His Merrion Square<br />

house is shown in his possession even after his<br />

death; 14 it may have lain vacant or it may have been<br />

occupied by his son-in-law Henry Montague Browne<br />

before it was legally transferred to him in 1825.

6<br />

No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square, Dublin 2<br />

1825–1835 Very Reverend Honourable Henry Montague<br />

Browne, Glebe House, Mullingar 15<br />

Browne (1799–1884), son of James Caulfield Browne,<br />

2nd Baron Kilmaine, Co Mayo, was later Dean of<br />

Lismore of the Church of Ireland. He was married to the<br />

Honourable Catherine Penelope de Montmorency,<br />

daughter of Lodge Evans Morres/ de Montmorency,<br />

Baron Frankfort, and was an executor of the latter’s will.<br />

1835–1865 William Smith, Lisaniskeir, Co Dublin, barrister 16<br />

Smith (born 1801) was the eldest son of Aquila Smith of<br />

Dublin and Catherine Doolan, and was educated at<br />

Gray’s Inn, London. 17 He was admitted to the <strong>Irish</strong> Bar<br />

in 1839, 18 and was appointed Registrar of the Land<br />

Commission in 1881. 19<br />

1866–1898 Major Henry Taaffe-Farrell (later Ferrell) JP, DL,<br />

Moylurg House, Boyle, Co Roscommon; Junior<br />

United Services Club, London; Kildare Street Club 20<br />

Ferrall (c. 1832–98) was a prominent Roscommon landowner,<br />

Sheriff and Deputy Lieutenant for Co Roscommon,<br />

and Hon. Lieutenant-Colonel of the 3rd Battalion of the<br />

Connaught Rangers from 1877. A leading <strong>Irish</strong> Unionist and<br />

a Catholic, he was also a long-term member of the Board of<br />

Guardians of the South Dublin Union.<br />

1898–1906 Mrs Alice Taaffe-Ferrall (née Keogh) 21<br />

1907–1936 Professor Robert Dwyer Joyce, FRCS, MECSE,<br />

ophthalmic and aural surgeon 22<br />

Joyce (c. 1874–1959) was the son of Patrick Weston<br />

Joyce (1827–1914), the famous Limerick-born<br />

collector of <strong>Irish</strong> traditional music, historian and educationalist,<br />

and was the nephew of the poet, song-writer<br />

and medical doctor Robert Dwyer Joyce (1830–1883),<br />

author of the songs ‘The Boys of Wexford’, ‘The Wind<br />

that Shakes the Barley’, etc. He qualified in London in<br />

1895 and become a Fellow of the Royal College of<br />

Surgeons in Ireland in 1899. In the Census of 1911 he<br />

is shown as an <strong>Irish</strong> speaker, living in no <strong>73</strong> with his<br />

wife Mary and four daughters and three servants – a<br />

parlour maid, a cook, and a servant maid. 23

The Premises of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> 7<br />

Joyce was a consulting ophthalmic surgeon in Holles<br />

Street hospital; ophthalmic surgeon in the Mater and<br />

Richmond hospitals; and from 1935 Professor of<br />

Ophthalmology in University College Dublin. 24<br />

About 1936 he moved to live in Ballsbridge, with<br />

consulting rooms at 11 Merrion Square. 25<br />

P.W. Joyce – who must often have been a visitor to this<br />

house – and his brother R.D. Joyce are well<br />

represented in the ITMA collections. During the period<br />

of his son’s residency in no <strong>73</strong>, P.W. Joyce was<br />

president of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland<br />

at 63 Merrion Square (former home of the ITMA,<br />

1991–2006). The Society published there in 1909 his<br />

final collection Old <strong>Irish</strong> Folk <strong>Music</strong> and Song.<br />

P.W. Joyce and the title page of his 1909 magnum opus<br />

1936–1947 Department of Local Government & Public<br />

Health; Department of Agriculture 26<br />

In 1936 the title to the building was purchased by the<br />

Commissioners of Public Works from members of the<br />

Malone and Price families at a cost of £1,600, with<br />

£50 annual ground rent payable to the Earl of<br />

Montgomery & Pembroke. The premises were<br />

assigned to the Combined Purchasing Section of the<br />

Departments of Local Government and Public Health.<br />

In 1941 the mews of no <strong>73</strong> was converted to a<br />

veterinary store for the Department of Agriculture. 27

8<br />

No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square, Dublin 2<br />

1947–1949 Department of Lands 28<br />

1950–1953 Department of Social Welfare 29<br />

1953–1990 <strong>Irish</strong> Manuscripts Commission & <strong>Irish</strong> Land<br />

Commission (Solicitors Branch) 30<br />

1991–2005 <strong>Irish</strong> Manuscripts Commission & <strong>Irish</strong><br />

Architectural <strong>Archive</strong> 31<br />

2006– <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong><br />

In July 2006 the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> moved<br />

from its former home at no 63 Merrion Square to no <strong>73</strong>.<br />

The building had been allocated to the ITMA by the<br />

Office of Public Works, which had refurbished it<br />

extensively from 2005 under the direction of OPW<br />

Senior Architect Niall Parsons. The ITMA was opened<br />

officially there on 15 November 2006 by Mr John<br />

O’Donoghue TD, Minister for Arts, Sport & Tourism.<br />

The ITMA is a national public archive and resource centre for all with an<br />

interest in the contemporary artforms of <strong>Irish</strong> traditional song, instrumental<br />

music, and dance. It was founded with the primary aims of collecting,<br />

preserving and organising the materials of <strong>Irish</strong> traditional music, and of<br />

making the materials and information held as widely available as possible<br />

to the general public.<br />

It holds the largest multi-media collection in existence of the materials of<br />

<strong>Irish</strong> traditional music: currently over 29,000 commercial and noncommercial<br />

sound recordings, 20,000 books and serials, 12,000<br />

photographs and negatives, 9,000 melodies in digital form, 7,000 ballad<br />

sheets and items of sheet music, 3,000 programmes, 2,000 videotapes and<br />

DVDs, and a mass of other materials such as posters and flyers. It also<br />

holds the largest body in existence of information about the music,<br />

organised on unique computer catalogues. A systematic programme has<br />

begun of making the catalogues and digitised materials available on the<br />

Internet via the ITMA website www.itma.ie.<br />

The materials and information held are made fully available for reference to<br />

all visitors to the ITMA. Guidance to the collections is given, and general<br />

information and consultancy on the music. An information service is also<br />

given directly by phone, post and fax, and remotely through the ITMA<br />

website. Materials and information are also made available through lectures,

10<br />

No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square, Dublin 2<br />

exhibitions and publications by ITMA staff, and through the ITMA’s<br />

extensive cooperation with the performing, teaching, broadcasting,<br />

publishing and archival activities of others, including RTÉ Radio and<br />

Television, TG4 Television, The Journal of <strong>Music</strong> in Ireland, Na Píobairí<br />

Uilleann, the Ulster Folk & Transport Museum, Gael Linn, etc., etc.<br />

The ITMA currently has a core staff of ten, with other part-time workers. Its<br />

operations are directed by a Board of twelve with performing, collecting,<br />

broadcasting, archival, financial, marketing and management experience.<br />

Users of the ITMA include singers, musicians, dancers, private-interest<br />

listeners, students at all levels, teachers, researchers and writers, librarians,<br />

broadcasters and publishers, arts administrators, and the general public, a<br />

significant number of whom come from abroad.<br />

The ITMA is funded by the Arts Council/ An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Dublin<br />

and also by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland in Belfast, and by<br />

individual donors, especially through its support group Friends of the <strong>Irish</strong><br />

<strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong>. It receives project funding from sponsors such<br />

as the Heritage Council, Cairde na Cruite, Temple Bar Cultural Trust, and<br />

the Ireland Newfoundland Partnership. In addition it receives support in<br />

kind from publishers and hundreds of private donors.<br />

The new ITMA premises in no <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square have public rooms<br />

equipped for listening to, viewing, reading, and studying items from the<br />

collections and accessing its databases; an audio and video recording studio;<br />

specialist rooms for the preservation, processing, copying and cataloguing<br />

of audio, video and print materials; reception and administrative areas; and<br />

specialist storage areas.

The Premises of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> 11<br />

OTHER HOUSES ON <strong>MERRION</strong> <strong>SQUARE</strong><br />

Remarkably, for an area that was once a bastion of British culture, other<br />

houses on Merrion Square also have longstanding associations with<br />

<strong>Irish</strong> traditional music.<br />

David Richard Pigot & John Edward Pigot<br />

At no 80 Merrion Square the Right Honourable David Richard Pigot<br />

(1797–18<strong>73</strong>), the Chief Baron of the <strong>Irish</strong> Exchequer from 1846 and a<br />

barrister originally from Cork, lived from 1834. A colleague of Daniel<br />

O’Connell (who lived at no 58), and a Vice-President of the Society for the<br />

Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland from its foundation<br />

in 1851, he was a contributor of traditional tunes to the collections of the<br />

artist and antiquarian George Petrie (1790–1866), the foremost nineteenthcentury<br />

collector of <strong>Irish</strong> traditional music. The ITMA holds original manuscripts<br />

of Petrie and copies of his music collections.<br />

David Pigot’s son, the Cork-born barrister John Edward Pigot (pen-name<br />

‘Fermoy’, 1822–71) lived at no 80 until 1851. He was an active collector<br />

of traditional music from the 1840s to the 1860s, and was joint Honorary<br />

Secretary from 1851 of the Society for the Preservation and Publication<br />

of the Melodies of Ireland. His manuscript collection of over 3,000 tunes<br />

is now in the Royal <strong>Irish</strong> Academy. A friend of Thomas Davis (who lived<br />

on Baggot Street), Pigot was a music editor of the Young Irelander newspaper<br />

The Nation in the 1840s, and the music editor of John O’Daly’s<br />

1849 Dublin-published collection The Poets and Poetry of Munster. 32 A<br />

copy of Pigot’s RIA manuscript and of various editions of the Nation<br />

songs and the O’Daly volume are held in the ITMA.<br />

‘Sagairt tar teóradh’, a melody contributed to George Petrie’s traditional music<br />

collections by David Richard Pigot, published by Charles Villiers Stanford ed.,<br />

The Complete Petrie Collection of <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Music</strong> (London 1902–05)

12<br />

No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square, Dublin 2<br />

‘Inghin an Fhaoit ón nGleann’, a melody from the manuscripts of John Edward<br />

Pigot in the Royal <strong>Irish</strong> Academy, Dublin, published by P.W. Joyce in his Old <strong>Irish</strong><br />

Folk <strong>Music</strong> and Songs (Dublin 1909)<br />

James Clarence Mangan<br />

At no 28 Merrion Square the Dublin poet James Clarence Mangan<br />

(1803–49) was employed as a clerk from about 1826 to 1829. 33 He made<br />

versions in English of <strong>Irish</strong>-language traditional songs, most notably for<br />

John O’Daly’s collection The Poets and Poetry of Munster and<br />

including the famous ‘Dark Rosaleen’. Presumably he collaborated with<br />

John Edward Pigot, music editor of the volume. Mangan was later<br />

employed by George Petrie as a scrivener for the Ordnance Survey. The<br />

ITMA holds several editions of the O’Daly collection and copies of<br />

other published Mangan-related and O’Daly-related material.<br />

George Petrie (left), James Clarence Mangan, Breandán Breathnach

The Premises of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> 13<br />

The Society for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of<br />

Ireland 1851<br />

Many of those prominently involved in the Society for the Preservation<br />

and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland, the first formal <strong>Irish</strong><br />

traditional music society, lived on Merrion Square or in its vicinity. The<br />

Society was established under the presidency of George Petrie in<br />

December 1851, in the aftermath of the Great Famine, to preserve, study<br />

and publish ‘the immense quantity of National <strong>Music</strong> still existing in<br />

Ireland’. 34 It was directed by a twenty-three-man Council. As well as<br />

David Richard Pigot and John Edward Pigot, Thomas Beatty MD and<br />

William Stokes MD lived on the Square, at nos 18 and 5 respectively. In<br />

the vicinity of the Square lived the Treasurer of the Society Robert<br />

Callwell (Herbert Place), its other joint Hon. Secretary Robert D. Lyons<br />

MD (Merrion Street), Rev. Charles Graves DD (Fitzwilliam Square),<br />

Benjamin Lee Guinness (Dawson Street), Thomas Rice Henn (Upper<br />

Mount Street), Henry Hudson and Samuel Maclean (St Stephen’s Green),<br />

Joseph Huband Smith (Holles Street), Rev. Jas. H. Todd (Trinity<br />

College), and William Wilde (later Sir William, father of Oscar; Westland<br />

Row). 35 Most of those associated with the Society were members of the<br />

Royal <strong>Irish</strong> Academy, which was then situated in Grafton Street.<br />

One of the aims of the Society, never realised, was ‘the formation of a<br />

central depôt in Dublin, to which persons... may be invited to send<br />

copies of any airs which they can obtain, either in Ireland or among our<br />

countrymen in other lands’. 36 The <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> might<br />

be said to be a realisation of that aim. Its collections contain the<br />

published works of the Society and later editions of them.<br />

The Arts Council & Breandán Breathnach<br />

The Arts Council/ An Chomhairle Ealaíon, the <strong>Irish</strong> state’s development<br />

agency for the arts (including the traditional arts), has been based in no<br />

70 Merrion Square since 1959. In 1980 it appointed a <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong><br />

Officer for the first time, and it currently has a <strong>Traditional</strong> Arts section<br />

through which it funds traditional artists, projects, festivals, and arts<br />

organisations (including the ITMA) – see www.artscouncil.ie.<br />

From the early 1980s until his death, Breandán Breathnach (1912–85),<br />

the great expert on <strong>Irish</strong> traditional music whose personal collection is<br />

the foundation collection of the ITMA, had an office in the basement of<br />

no 70 in which he worked principally on his monumental index of <strong>Irish</strong><br />

traditional dance music. A member of the Arts Council from 1984, he<br />

chaired for it a committee on the establishment of a national archive of<br />

traditional music and was the author of its report.<br />

— Nicholas Carolan

14<br />

No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square, Dublin 2<br />

Notes<br />

1 Registry of Deeds, Dublin, memorial no 300430 of lease dated 30 December 1786, for<br />

150 years from 29 September 1786, from Rt Hon. Richard Lord Fitzwilliam of Merrion<br />

to James Doyle, merchant of the city of Dublin. Wilson’s Dublin Directory shows ‘Doyle<br />

and Roe’ as wholesale merchants in Temple Bar from the 1780s to the 1790s. This is presumably<br />

the same Doyle since a Peter Roe developed the Merrion Square plot adjacent<br />

to James Doyle’s on the east (see The Statutes at Large, Passed in the Parliaments of<br />

Ireland... vol. XV, Grierson, Dublin, 1792, pp. 787–96, 31 Geo. III, 45: ‘An Act for<br />

Enclosing and Improving Merrion Square, in the City of Dublin’). A James Doyle,<br />

grocer, is also shown in the same decades with premises in Abbey Street and New Row.<br />

2 Registry of Deeds, Dublin, memorial no 292526 of indenture of lease, 19 August 1792,<br />

from James Doyle, City of Dublin, merchant, to Hon. John Stratford of the same city of<br />

a house etc. on the south side of Merrion Square, bound on the east by a new brick<br />

dwelling house belonging to Peter Roe, and on the west by another new brick dwelling<br />

house belonging to James Doyle. The lease ownership of no <strong>73</strong> (not to be confused with<br />

occupancy of the premises) passed from members of the Doyle family to members of<br />

the Malone family in 1856, to members of the related Price and Malone families in<br />

1898, 1899 and 1903, and from them to the Commissioners of Public Works in 1936<br />

(OPW, Property Management Division, file no D.20 1/5/44, p. 5).<br />

On 29 January 1796 Doyle sold another newly built brick house etc. on the south-west<br />

side of Merrion Square: ‘Bounding on the south east to premises belonging to the said<br />

James Doyle... and on the north west to Humphrey Worthingstons holding’ (Registry of<br />

Deeds, Dublin, memorial no 319805; a map of the Fitzwilliam Estate, now in the Pembroke<br />

Estate papers in the National <strong>Archive</strong>s and reproduced in Mary Clark & Alastair Smeaton,<br />

eds, The Georgian Squares of Dublin: An Architectural History, Dublin, 2006, p. 84, confirms<br />

this position of Doyle’s plot). This house is the present 74 Merrion Square, premises<br />

of the Central Catholic Library and also home to the <strong>Irish</strong> Georgian Society.<br />

See also Registry of Deeds, Dublin, memorial no 16, vol. 29 of 1865, of indenture<br />

of lease, 6 Sept. 1865, between William Smith of Merrion Square, barrister-at-law, and<br />

Henry Taaffe Farrell [sic], Raglan Rd, Co Dublin, ‘reciting that by indenture of Lease<br />

bearing date 13 [recte 19] August 1792 James Doyle demised unto John Stratford...<br />

Number 15 in said Square’. This latter memorial proves that no 15 and no <strong>73</strong> were one<br />

and the same house as the number is documented as having changed from 15 to <strong>73</strong><br />

during Taaffe Ferrall’s tenure (Thom’s Directory, issues of 1879 to 1881).<br />

3 See previous note.<br />

4 In 1816 the Fitzwilliam Estate passed into the possession of the Earl of Pembroke and<br />

became the Pembroke Estate, which it remains.<br />

5 For the general history of Merrion Square see Maurice Craig, Dublin 1660–1860: A<br />

Social and Architectural History, Cresset Press, London, 1952, and other editions;<br />

Nicola Matthews, ‘The Development of Merrion Square’, Masters in Urban & Building<br />

Conservations thesis, University College Dublin, 1997; Christine Casey, The Buildings<br />

of Ireland: Dublin, Yale, 2005; Clark & Smeaton as at Note 2 above; etc.<br />

6 See Edith Mary Johnson-Liik, History of the <strong>Irish</strong> Parliament 1692–1800. Commons,<br />

Constituencies and Statutes vol. vi, Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast, 2002, pp.<br />

366–7. See also Note 2 above. Samuel Watson’s The Gentleman’s and Citizen’s<br />

Almanack, Dublin, issues of 1796 to 1800, shows Stratford, then a member of the<br />

Commons of Ireland, living on Merrion Square at least from 1796 to 1800. The<br />

Almanack does not give the number of his house but Note 2 shows it to have been no 15.<br />

7 See Oxford Dictionary of National Biography vol. 58, Oxford University Press, Oxford,

The Premises of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> 15<br />

2004, pp. 23–4; and the online site www.thepeerage.com ‘Stratford’.<br />

8 Johnson-Liik 2002, vol. vi, p. 367.<br />

9 See G.E. Cokayne et al., eds, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, and the<br />

United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, London, 1910–59, vol. 1, p. 99; vol. 3, p. 17.<br />

10 Johnson-Liik 2002, vol. vi, p. 367.<br />

11 See Johnson-Liik 2002, vol. v, pp. 319–21. See also Wilson’s Dublin Directory, Dublin,<br />

for these years; and the online site www.thepeerage.com ‘De Montmorency’.<br />

12 Johnson-Liik 2002, vol. v, p. 320.<br />

13 The Times, London, 23 June 1796.<br />

14 Pigot & Co’s Provincial Directory of Ireland 1824, Dublin, 1824, p. 20.<br />

15 See Wilson’s Dublin Directory, Dublin, for these years; and the online site<br />

www.thepeerage.com ‘Browne’.<br />

16 Registry of Deeds, Dublin, memorial no 210, volume 4 of 1835, of deed of conveyance,<br />

dated 24 Feb. 1835, from Rt Hon. Viscount Frankfort de Montmorency (deceased), the<br />

Rt Hon. Henry Montague Browne of Mullingar (one of de Montmorency’s executors),<br />

and others, to William Smith, Co Dublin, Esquire. See also Note 2 above for the transfer<br />

of the premises from Smith to Taaffe Ferral.<br />

17 Edward Keane, P. Beryl Phair & Thomas U. Sadleir, eds, King’s Inn Admission Papers<br />

1607–1867, <strong>Irish</strong> Manuscript Commission, Dublin, 1982, p. 454.<br />

18 Pettigrew & Oulton’s Dublin Directory 1842, Dublin, 1842, p. 550.<br />

19 The Times, London, 11 Oct. 1881.<br />

20 The Downside Review, Bath, 1898, p. 310. See also Note 2 above and Thom’s<br />

Directory, Dublin, for these years. His name frequently appears in The <strong>Irish</strong> Times, as<br />

attending the Lord Lieutenant’s levee in Dublin Castle or involved in charitable Poor<br />

Law activities.<br />

21 See Kelly’s Handbook of the Titled, Landed and Official Classes, London, 1888, p. 1042;<br />

Thoms’s Directory, Dublin, for these years.<br />

22 See Thoms’s Directory, Dublin, for these years.<br />

23 National <strong>Archive</strong>s website www.census.nationalarchives.ie, census return for <strong>73</strong><br />

Merrion Square.<br />

24 <strong>Irish</strong> Times obituary, 21 January 1959, p. 10.<br />

25 Thom’s Directory, Dublin, 1938, which shows his home address as 10 Clyde Road.<br />

26 Thom’s Directory, Dublin, for these years.<br />

27 OPW, Property Management Division, file no D.20 1/5/44, pp. 5, 16.<br />

28 Thom’s Directory, Dublin, for these years.<br />

29 Ibid.<br />

30 Both organisations transferred to the premises in October 1953 (OPW, Property<br />

Management Division, file no D.20 1/5/44, p. 16). See also Thom’s Directory, Dublin,<br />

for these years.<br />

31 See www.irmss.ie and www.iarc.ie.<br />

32 See Nicholas Carolan, ‘The Forde-Pigot Collection of <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong>’ in<br />

Treasures of the Royal <strong>Irish</strong> Academy Library, Bernadette Cunningham, Siobhán<br />

Fitzpatrick, Petra Schnabel eds, RIA, Dublin, 2009.<br />

33 Eileen Shannon-Mangan, James Clarence Mangan: A Biography, <strong>Irish</strong> Academic<br />

Press, Dublin, 1996, pp. 65–75.<br />

34 George Petrie ed., The Petrie Collection of the Ancient <strong>Music</strong> of Ireland vol. 1, Society<br />

for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland, Dublin, 1855, p. v.<br />

35 Thom’s <strong>Irish</strong> Almanac and Official Directory... for the Year 1851, Dublin, 1851, pp.<br />

957–1122 passim.<br />

36 Petrie 1855, p. vi.

16<br />

No <strong>73</strong> Merrion Square, Dublin 2<br />

‘Labhairse féin mo chéile liom’, part of a traditional song-text sung by girl spinners,<br />

from original George Petrie manuscripts of the ITMA<br />

First published by the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong>/ Taisce Cheol Dúchais<br />

Éireann on 29 July 2008 as one of a series of events to mark the 21st<br />

anniversary of the establishment of the <strong>Archive</strong> on the same date in 1987<br />

Research & Text<br />

<strong>Music</strong> Setting<br />

Photography<br />

Scanning<br />

Drawings etc.<br />

Layout & Design<br />

Printing<br />

Nicholas Carolan<br />

Maeve Gebruers<br />

Treasa Harkin, Danny Diamond<br />

Mícheál Ó Catháin, Colum O’Riordan<br />

Courtesy Niall Parsons, OPW (inside and rear<br />

covers, p. 1), <strong>Irish</strong> Architectural <strong>Archive</strong> (p. 4)<br />

Jackie Small<br />

Hackett Reprographics, Dublin<br />

© <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> 2008, revised reprint 2009<br />

With thanks to the Chairman, Board and staff of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong><br />

<strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong>; to Maeve Carolan; to the staffs in Dublin of the Property<br />

Division of the Office of Public Works, Na Píobairí Uilleann, the <strong>Irish</strong><br />

Architectural <strong>Archive</strong>, the Registry of Deeds, the Dublin City Library<br />

and <strong>Archive</strong>, the Library of Trinity College Dublin, the Royal Society of<br />

Antiquaries of Ireland, and the National Library of Ireland; to all who<br />

have enabled the growth of the ITMA to date by the donation of material<br />

and information; to the support group Friends of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong><br />

<strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong> and other project funders for financial support; to the<br />

Mícheál Ó Domhnaill Trust for the funding of this 2009 reprint; to the<br />

Office of Public Works; and to the Arts Council/ An Chomhairle Ealaíon<br />

in Dublin and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland in Belfast who are<br />

the major funders of the <strong>Irish</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> <strong>Archive</strong>