IC 76003 Booklet - Ivory Classics

IC 76003 Booklet - Ivory Classics

IC 76003 Booklet - Ivory Classics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Accolades<br />

7<br />

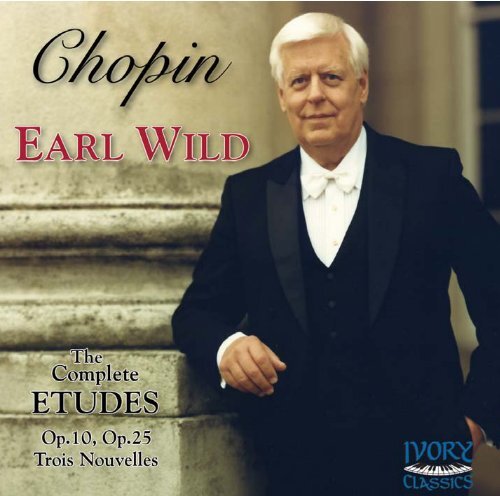

“Earl Wild is still Earl Wild”<br />

“The reason Mr. Wild’s Chopin keeps us<br />

unfailingly mesmerzerized is the endless and<br />

absoulte poetry of his glowing performance.”<br />

“No rickety joints here at 77, just pure motion<br />

and artistry, with the fluid technique and<br />

musical depth of a seasoned artist.”<br />

“This is Mr. Wild’s ‘magic’, with age has<br />

come a great wondrous wisdom.”

Chopin Etudes<br />

EARL WILD<br />

Twelve Etudes, Op. 10 Twelve Etudes, Op. 25<br />

1) No. 1 in C Major 2:15 13) No. 1 in A-flat Major 2:40<br />

2) No. 2 in A minor 1:35 14) No. 2 in F minor 1:30<br />

3) No. 3 in E Major 4:26 15) No. 3 in F Major 1:51<br />

4) No. 4 in C-sharp minor 2:07 16) No. 4 in A minor 1:51<br />

5) No. 5 in G-flat Major 1:43 17) No. 5 in E minor 3:11<br />

6) No. 6 in E-flat minor 3:45 18) No. 6 in G-sharp minor 2:02<br />

7) No. 7 in C Major 1:36 19) No. 7 in C-sharp minor 5:03<br />

8) No. 8 in F Major 2:26 20) No. 8 in D-flat Major 1:10<br />

9) No. 9 in F minor 2:04 21) No. 9 in G-flat Major :58<br />

10) No. 10 in A-flat Major 2:09 22) No. 10 in B minor 3:46<br />

11) No. 11 in E-flat Major 2:30 23) No. 11 in A minor 3:38<br />

12) No. 12 in C minor 2:32 24) No. 12 in C minor 2:39<br />

Trois Nouvelles Etudes<br />

25) No. 1 in F minor 2:15<br />

26) No. 2 in A-flat Major 1:46<br />

27) No. 3 in D-flat Major 1:48<br />

Total Time: 66:48<br />

– 2 –

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)<br />

The Complete ETUDES<br />

The tragedy that so brilliant a prodigy as Frédéric Chopin should have<br />

lived so brief a life is one of the great laments of humankind. Born in 1810<br />

in Zelazowa Wola, Poland, he was dead by the year 1849, when at age thirty-nine<br />

he succumbed to frailty and sickliness in Paris, which had been his<br />

home since 1831. As a pianist he performed in public only rarely and reluctantly,<br />

in an exquisitely delicate and ephemeral style. In 1836 Henrietta Voigt<br />

said that “wonderful is the ease with which his velvet fingers glide, I might<br />

say fly, over the keys… What delighted me was the childlike, natural manner<br />

which he showed in his demeanor and in his playing.”<br />

Though Chopin’s hands were not large, they were flexible, enabling him<br />

to maneuver wide stretches without the least apparent exertion. According to<br />

Carl Mikuli he recommended bending the wrist inward and outward and<br />

pressing the fingers apart, but without over-exertion. For practicing scales he<br />

insisted on a very full tone, as legato as possible, with metronomic steadiness.<br />

Perhaps most importantly, he held that evenness in playing scales and arpeggios<br />

depended not only on the equality of strength of the five fingers, “and a<br />

perfect freedom of the thumb in passing under and over, but foremostly on<br />

the perfectly smooth and constant sideways movement of the hand (not step<br />

by step), letting the elbow hang down freely and loosely at all times.” He<br />

– 3 –

taught scales with many black notes first (the C major scale came last as the<br />

most difficult), using the thumb on the black notes and sometimes passing it<br />

under the fifth finger (with a necessary bend of the wrist).<br />

The piano was in transition in Chopin’s day, having evolved from a delicate<br />

wooden instrument to a bold instrument with a very different key<br />

action and a reinforced soundboard, allowing richer sympathetic vibrations<br />

and increased carrying power for the concert hall. In Paris at that time there<br />

were some 180 manufacturers producing a wide range of experimental<br />

pianos, leading its citizens to refer to their city as Pianopolis. Some manufacturers<br />

developed a more expressive instrument, one equal to the demands<br />

of Chopin’s works.<br />

Countless piano studies were composed in the eighteenth century and<br />

early in the nineteenth by the likes of Berger, Moscheles, Hummel, Steibelt,<br />

Reicha, Czerny, Cramer, Kalkbrenner and Clementi. Their starkly educational<br />

purpose was strictly to perfect the techniques needed to play the repertoire<br />

of the day, and they thus lacked the musical and affective properties required<br />

for pieces intended for the public. Chopin’s etudes, however—twenty-seven<br />

of them in all—eclipsed the earlier models and led piano technique to the<br />

next logical step, exploiting the new resources of the evolving instrument,<br />

and all its color possibilities, and exploring revolutionary techniques through<br />

their stunning inventiveness. Each study concentrates on a single technical<br />

problem and fully exploits the possibilities of the human hand, so much so<br />

that a leery Ludwig Rellstab wrote that “those who have crooked fingers may<br />

put them right by practicing these studies; but those who have not, should<br />

– 4 –

not play them, at least not without having a surgeon at hand.” Composed<br />

between 1829 and 1839 (in a sequence different from their numbering), the<br />

etudes represent Chopin’s early maturity—written between his late teens and<br />

his late twenties—and possess a youthful vigor not seen in his later works.<br />

They launched the modern school of piano playing.<br />

But the real genius of the etudes lies in the poetry by which they surpass<br />

all precedents, thus constituting the new genre of the concert-etude. They are<br />

boldly creative expressions of human emotion, studies in mood, inventively<br />

encapsulated in vignettes of virtuosity. Chopin admonished his students to<br />

make the piano sing and to express personal emotion, never using technical<br />

exercises in a mechanical way, but investing them with intelligence and will.<br />

Indeed, the etudes succeed resoundingly at melding formidable technique<br />

with fresh musical expression. As James Huneker has written: The etudes are<br />

“not only the foundation of [Chopin’s] technical system—a system new to<br />

pianism when they appeared—but they also comprise some of his most imaginative<br />

and enchanting creations, judged exclusively from the musical point<br />

of view.” All the etudes are marked either allegro, vivace, presto or agitato—<br />

apart from three lentos and two andantes—making them fiendishly difficult<br />

pieces and explaining why they are the only Chopin works Arthur Rubinstein<br />

refused to record (Although Mr. Wild performed the complete etudes many<br />

times throughout his career, he waited to record them until he was seventyseven).<br />

They have appeared in a number of editions over the years.<br />

Chopin wrote of his etudes that he “tried to put not only science but<br />

also art into them. Since a virtuoso must practice for a long time, he should<br />

– 5 –

e given exercises in which he will find proper food for his ears and his soul<br />

lest he be bored to death. I am disturbed because there are no beautiful exercises<br />

for beginners. A virtuoso has everything open to him; when he is bored<br />

by exercises, he can reach out for the most beautiful music. But a poor fellow<br />

who cannot play anything except exercises, whose fingers are as though<br />

tied, needs beautiful exercises that will save him from becoming disgusted<br />

with music. I have tried to write something of this kind, but I haven’t been<br />

successful, because for the beginner anything is too difficult.”<br />

Pianists began recording Chopin’s etudes in the nineteenth century. The<br />

earliest were probably the random samplings of them by a variety of pianists<br />

(including Horowitz) who recorded single movements on the pneumatic<br />

Welte-Mignon recording system, perfected in the 1890s. In terms of fidelity,<br />

the device far exceeded all other approaches to piano roles, including especially<br />

the gramophone and cylinder records of the period. But the first<br />

pianist to record the complete opus 10 and 25 was Wilhelm Backhaus.<br />

The opus 10 etudes were published as a set in 1833 and dedicated to<br />

Franz Liszt, whom Chopin considered their best interpreter. No. 1 is a study<br />

for extended right-hand arpeggios, often with a stretch of six notes between<br />

adjacent fingers. No. 2 explores chromatic scales for the weak fingers 3, 4<br />

and 5 of the right hand. Chopin said of No. 3 that he had never written so<br />

beautiful a melody. It involves playing three continuous voices with the two<br />

hands, and has been called a study in expression. The sheer velocity and<br />

pyrotechnics of No. 4, with frequent shifts of the melody between the hands,<br />

make it one of the most exciting of the studies. Apart from a single white<br />

– 6 –

note, the right hand in No. 5 plays exclusively black notes, giving it a pentatonic<br />

character. One of the easier pieces, the elegiac melody of No. 6 nevertheless<br />

places musical demands on the performer. A toccata with repeated<br />

notes in the right hand, No. 7 alternates thirds and sixths, the lower note of<br />

which requires changing fingers. With simple chords in the left hand, the<br />

right hand in No. 8 is a study in arpeggios covering the spread of four<br />

octaves. No. 9 is a turbulent study in repeated notes, with arpeggios of a<br />

tenth or more in the left hand. In No. 10 the alternating sixths and broken<br />

octaves require a flexible wrist in rhythms of two against three. Von Bülow<br />

said of it that “anyone who can play this etude in a really finished manner<br />

may be congratulated on having climbed to the highest point of the pianists’<br />

Parnassus.” No. 11 is a study in harp-like chords covering the range of twoand-a-half<br />

octaves in both hands. The only etude known to have been<br />

inspired by events in his life, Chopin is said to have composed No. 12 after<br />

learning that Warsaw had fallen to the Russians. It involves tumultuous<br />

arpeggios in the left hand, and a forbidding melody in octaves in the right.<br />

The opus 25 etudes were published in a single volume in 1837, and are<br />

dedicated to Liszt’s mistress, the Countess Marie d’Agoult who bore his children.<br />

Robert Schumann heard Chopin play No. 1 and wrote: “Imagine an<br />

Aeolian harp having all the scales and the hand of an artist combining them<br />

with all kinds of fantastic embellishments, but always with an audible deep<br />

tone in the bass and a softly singing melody in the treble, and you will get<br />

some idea of Chopin’s playing. When the etude was ended, we felt as<br />

though we had seen a radiant picture in a dream which, half awake, we<br />

– 7 –

ached to recall.” The technical challenge in No. 2 is to play the triplet eighthnotes<br />

in the right hand and the triplet quarter-notes in the left with an unaccented<br />

quality. The capricious No. 3 pits the gestures in the right hand<br />

against those of the left, and layers four motives upon each other in every<br />

beat. No. 4 is a nervous study in syncopation and staccato. No. 5 explores<br />

leggiero and scherzando with grace notes and passing tones, and in the slow<br />

section contains one of Chopin’s most beautiful melodies. No. 6 is a study in<br />

rapid thirds while No. 7, with the sweet sadness of its left-hand melody, is<br />

perhaps the most poetic of the lot. No. 8 is a study in parallel double sixths.<br />

In No. 9 the right hand plays a broken chord and two staccato octaves on<br />

every beat. The furious No. 10 presents the challenge of rapid chromatic<br />

legato octaves in both hands, and has a lyrical middle section. Chopin<br />

warned students that the march-like No. 11 “can be treacherous and dangerous<br />

for the uninitiated.” No. 12 involves fast arpeggios in both hands.<br />

Beginning in m. 40 Mr. Wild plays octaves on the first beat of every measure<br />

in a version favored by Rachmaninoff.<br />

The Trois Nouvelles Etudes, published in 1840 without an opus number,<br />

are erroneously known as the posthumous etudes; in fact they were published<br />

while Chopin was still alive. No. 1 is characterized by the cross rhythms of<br />

triplet quarters against four eighth-notes. Following the example of Liszt, Mr.<br />

Wild plays a repeat beginning at measure 22. No. 2 is a study in three against<br />

two, and No. 3 involves simultaneous staccato and legato in the right hand.<br />

– 8 –<br />

© James E. Frazier 2006

Earl Wild<br />

Earl Wild is a pianist in the grand Romantic tradition. Considered by<br />

many to be the last of the great Romantic pianists, this eminent musician is<br />

known internationally as one of the last in a long line of great virtuoso<br />

pianist / composers. Often heralded as a super virtuoso and one of the<br />

Twentieth Century’s greatest pianists, Earl Wild is a legendary figure performing<br />

throughout the world for over eight decades.<br />

Major recognition is something Mr. Wild has received numerous times<br />

in his long career. He was included in the Philips Records series entitled The<br />

Great Pianists of the 20th Century with a double disc devoted exclusively to<br />

piano transcriptions. He has been featured in TIME Magazine on two separate<br />

occasions, most recently in December of 2000 honoring his eighty-fifth<br />

birthday. One of only a handful of living pianists to merit an entry in The<br />

New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Mr. Wild is therein described<br />

as a pianist whose technique “is able to encompass even the most difficult<br />

virtuoso works with apparent ease.”<br />

Earl Wild was born on November 26, 1915 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.<br />

As a child Earl Wild’s parents would often play opera overtures (such as the<br />

one from Bellini’s Norma) on their Edison phonograph. At three, he would<br />

go to the family piano, reach up to the keyboard, find the exact notes, and<br />

play along in the same key. At this early age, he displayed the rare gift of<br />

absolute pitch. This and other feats labeled him as a child prodigy and led<br />

– 9 –

immediately to piano lessons.<br />

At six, he had a fluent technique and could read music easily. Before his<br />

twelfth birthday, he was accepted as a pupil of the famous teacher Selmar<br />

Janson, who had studied with Eugen d’Albert (1864-1932) and Xaver<br />

Scharwenka (1850-1924), both students of the great virtuoso pianist / composer<br />

Franz Liszt (1811-1886). He was then placed into a program for artistically<br />

gifted young people at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Tech (the Institute of<br />

Technology) -- now Carnegie Mellon University. Enrolled throughout Junior<br />

High, High School, and College years, he graduated from Carnegie Tech in<br />

1937. By nineteen, he was a concert hall veteran.<br />

He was invited at the age of twelve to perform on radio station KDKA in<br />

Pittsburgh (the first radio station in the United States). Mr. Wild had already<br />

composed many compositions and piano transcriptions as well as arrangements<br />

for chamber orchestra that were regularly performed on KDKA radio.<br />

At twelve, he made such an impression that he was asked to work for the station<br />

on a regular basis for the next eight years. Mr. Wild was only fourteen<br />

when he was hired to play the Piano and Celeste in the Pittsburgh Symphony<br />

Orchestra under the batons of many different conductors; Otto Klemperer<br />

and Fritz Reiner being two of the more well-known personalities.<br />

Mr. Wild’s other teachers included the great Dutch pianist Egon Petri<br />

(1881-1962), who was a student of Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924); the distinguished<br />

French pianist Paul Doguereau (1909-2000), who was a pupil of<br />

Ignace Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) and Marguerite Long (1874-1966), who<br />

studied the works of Gabriel Fauré and Claude Debussy with Jean Roger-<br />

– 10 –

Ducasse (1873-1954 - a pupil of Fauré’s), and was a friend and protégé of<br />

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Mr. Wild also studied with Helene Barere, the<br />

wife of the famous Russian virtuoso pianist, Simon Barere (1896-1951), and<br />

with Volya Cossack, a pupil of Isidore Philippe (1863-1958), who had studied<br />

with Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921).<br />

With immense hands, absolute pitch, graceful stage presence, and<br />

uncanny facility as a sight-reader and improviser, Earl Wild was well<br />

equipped for a lifelong career in music.<br />

During this early teenage period of his career, Earl Wild gave a brilliant<br />

and critically well received performance of Liszt’s First Piano Concerto in E-<br />

flat with Dimitri Mitropoulos and the Minneapolis Symphony in Pittsburgh’s<br />

Syria Mosque Hall. Performing the work without the benefit of a rehearsal.<br />

In 1937, he joined the NBC network in New York City as a staff pianist.<br />

This position included not only the duties of playing solo piano and chamber<br />

recitals, but also performing in the NBC Symphony Orchestra under<br />

conductor Arturo Toscanini. In 1939, when NBC began transmitting its first<br />

commercial live musical telecasts, Mr. Wild became the first artist to perform<br />

a piano recital on U.S. television. In 1942, Toscanini added a dimension to<br />

Earl Wild’s career when he invited him to be the soloist in an NBC radio<br />

broadcast of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue.<br />

It was the first performance of the Rhapsody for both conductor and<br />

pianist, and although Mr. Wild had not yet played any of Gershwin’s other<br />

compositions, he was immediately hailed as the major interpreter of<br />

Gershwin’s music. The youngest (and only) American piano soloist ever to<br />

– 11 –

perform with the NBC Symphony and Maestro Toscanini, Mr. Wild was a<br />

member of the orchestra and worked for the NBC radio and television<br />

network from 1937 to 1944.<br />

During World War II, Mr. Wild served for two years in the United States<br />

Navy as a musician, playing 4th flute in the Navy Band. He also performed<br />

numerous solo piano recitals at the White House for President Franklin D.<br />

Roosevelt and played twenty-one different piano concertos with the U.S.<br />

Navy Symphony Orchestra at the Departmental Auditorium, National<br />

Gallery, and other venues in Washington, D.C. During those two years in<br />

the Navy he was frequently requested to accompany First Lady Eleanor<br />

Roosevelt to her many speaking engagements, where he performed the<br />

National Anthem as a prelude to her speeches.<br />

Upon leaving the Navy in 1944, Mr. Wild moved to the newly formed<br />

American Broadcasting Company (ABC), where his duties consisted of being<br />

staff pianist, conductor, and composer where he conducted and performed<br />

many of his own compositions – he stayed at ABC until 1968. During both<br />

his NBC and ABC affiliations he was also a traveling musician, performing<br />

and conducting many concert engagements around the world. In 1962, the<br />

ABC network commissioned him to compose an Easter Oratorio. It was the<br />

first time that a television network subsidized a major musical work. Mr.<br />

Wild was assisted by tenor William Lewis, who wrote the libretto and also<br />

sang the role of St. John in the production. Mr. Wild’s composition titled,<br />

Revelations was a religious work based on the apocalyptic visions of St. John<br />

the Divine. Mr. Wild also conducted its world premiere telecast in 1962,<br />

– 12 –

which blended dance, music, song, and theatrical staging. The large-scale<br />

oratorio was sung by four soloists and chorus and was written in three sections:<br />

Seal of Wisdom, The Seventh Angel, and The New Day. The first telecast was so<br />

successful that it was entirely restaged and rebroadcast on TV once again in<br />

1964.<br />

Earl Wild has participated in many premieres. In 1944 on NBC radio,<br />

he performed the Western World premiere of Shostakovich’s Piano Trio in E<br />

minor. In France, in 1949, he was soloist in the world premiere performance<br />

of Paul Creston’s Piano Concerto. He gave the American premiere of the same<br />

work with the National Symphony in Washington, D.C. the next year. In<br />

December of 1970, with Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony, Mr.<br />

Wild gave the world premiere of Marvin David Levy’s Piano Concerto, a work<br />

specially written for him.<br />

Mr. Wild has had the unequaled honor of being requested to perform<br />

for six consecutive Presidents of the United States, beginning with President<br />

Herbert Hoover in 1931. In 1961 he was soloist with the National<br />

Symphony at the inauguration ceremonies of President John F. Kennedy in<br />

Constitution Hall – a legendary performance that has been historically<br />

preserved and made available through the National Symphony on their<br />

75th Anniversary 4-CD set.<br />

A common element among the great pianists of the past and Earl Wild is<br />

the art of composing piano transcriptions. Mr. Wild has taken his place in<br />

history as a direct descendant of the golden age of the art of writing piano<br />

transcriptions. Often called “The finest transcriber of our time,” Earl Wild and<br />

– 13 –

his numerous piano transcriptions are widely known and respected. Over<br />

the years they have been performed and recorded by pianists worldwide.<br />

In 1986, on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the death of<br />

Franz Liszt, Earl Wild was awarded a Liszt Medal by the People’s Republic<br />

of Hungary in recognition of his long and devoted association with this legendary<br />

composer’s music.<br />

Liszt is a composer who has been closely associated with Mr. Wild<br />

throughout his long career - he has been performing Liszt recitals for well<br />

over sixty years. Championing composers such as Franz Liszt, Nikolai<br />

Medtner, Ignace Jan Paderewski, Xaver Scharwenka, Karl Tausig, Mily<br />

Balakirev, Eugen d’Albert, Moriz Moszkowski, Reynaldo Hahn and countless<br />

others long before they were “fashionable” is part of the foundation on<br />

which Mr. Wild has built his long and successful career.<br />

In addition to pursuing his own concert and composing career, Earl<br />

Wild has actively supported young musicians all his life. Over the years he<br />

has taught at Eastman, Penn State, Manhattan School, Ohio State and The<br />

Juilliard Schools of Music. He currently holds the title of Distinguished<br />

Visiting Artist at his alma mater, Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.<br />

Carnegie Mellon has honored Mr. Wild with both their Alumni Merit Award<br />

and their more prestigious Distinguished Achievement Award.<br />

Mr. Wild has appeared with nearly every orchestra and performed<br />

countless recitals in virtually every country. In the past ninety years he<br />

has collaborated with many eminent conductors including: Toscanini,<br />

Stokowski, Reiner, Klemperer, Horenstein, Leinsdorf, Fiedler,<br />

– 14 –

Mitropoulos, Grofe, Ormandy, Sargent, Dorati, Maazel, Solti, Copland,<br />

and Schippers. Additionally, Earl Wild has performed with violinists:<br />

Mischa Elman, Oscar Shumsky, Ruggerio Ricci, Mischa Mischakoff, and<br />

Joseph Gingold; violists: William Primrose and Emanuel Vardi; cellists:<br />

Leonard Rose, Harvey Shapiro, and Frank Miller; and singers: Maria<br />

Callas, Jenny Tourel, Lily Pons, Marguerite Matzenauer, Dorothy Maynor,<br />

Lauritz Melchior, Robert Merrill, Mario Lanza, Jan Peerce, Zinka Milanov,<br />

Grace Bumbry, and Evelyne Lear.<br />

Highlights include a March 1974 joint recital with Maria Callas as a<br />

benefit for the Dallas Opera Company and a duo recital with famed<br />

mezzo-soprano Jennie Tourel in New York City in 1975.<br />

In 1960, at the Santa Fe Opera, Earl Wild conducted the first seven<br />

performances of Verdi’s La Traviata ever performed in that Theatre, as well<br />

as conducting four performances of Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi on a double<br />

bill with Igor Stravinsky (who conducted his own opera Oedipus Rex).<br />

From 1952 to 1956 Mr. Wild worked with comedian Sid Caesar on<br />

the very popular TV program The Caesar Hour. During those years, he<br />

composed and performed all the solo piano backgrounds in the silent<br />

movie skits. He also composed most of the musical parodies and burlesques<br />

on operas that were so innovative that they have now become<br />

gems of early live television.<br />

In 1986 Mr. Wild was asked to participate in a television documentary<br />

titled, “Wild about Liszt,” which was filmed at Wynyard, the Marques of<br />

Londonderry’s family estate in Northern England. The program won the<br />

– 15 –

British Petroleum Award for best musical documentary that year.<br />

Mr. Wild is one of today’s most recorded pianists, having made his first<br />

disc in 1939 for RCA. His discography of recorded works includes more<br />

than 35 piano concertos, 26 chamber works, and over 700 solo piano pieces.<br />

In 1997, he received a GRAMMY Award for his disc devoted entirely too<br />

virtuoso piano transcriptions titled, Earl Wild - The Romantic Master (an 80th<br />

Birthday Tribute).<br />

For the first official release of the newly formed IVORY CLASS<strong>IC</strong>S label<br />

in 1997, Earl Wild recorded the complete Chopin Nocturnes (CD-70701),<br />

which the eminent New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg reviewed in<br />

the American Record Guide saying, “These are the best version of the<br />

Nocturnes ever recorded - even better than Rubinstein’s.”<br />

Since its inception, IVORY CLASS<strong>IC</strong>S has released twenty-five newly<br />

recorded or re-released performances featuring Earl Wild.<br />

In May of 2003 the eighty-eight year-old Dean of the Piano recorded a<br />

new CD of solo piano material he had never recorded before: Mozart –<br />

Sonata K.332; Beethoven - 32 Variations; Chopin – Four Impromptus;<br />

Balakirev – Sonata No.1 and Earl Wild – Mexican Hat Dance, all performed<br />

on the new limited edition Shigeru Kawai Concert Grand EX piano.<br />

For the year 2005, in which Earl Wild celebrated his ninetieth<br />

birthday, he recorded a new CD of four major works (Bach – Partita<br />

No.1, Scriabin – Sonata No.4, Franck – Prelude, Chorale & Fugue and<br />

Schumann - Fantasiestucke Op. 12).<br />

His historic year tour culminated with an extremely well-received 90th<br />

– 16 –

irthday recital at Carnegie Hall in New York City on November 29, 2005.<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> is proud to present several newly remastered CDs (such<br />

as the works on this disc) all of them featuring Mr. Wild’s performances of<br />

some of the world’s greatest repertoire for solo piano. Recent re-releases were<br />

the “Earl Wild Legendary Rachmaninoff Song Transcriptions” (CD-74001),<br />

released in 2004 and discs of Chopin’s Scherzos and Ballades (CD-75001) and<br />

solo works by Nikolai Medtner (CD-75003) which were both released in<br />

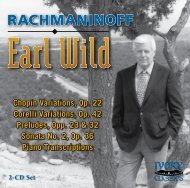

2005. In the coming months, <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> intends to re-release the following<br />

Earl Wild recordings: Rachmaninoff’s Variations on a Theme by<br />

Chopin, his Variations on a Theme by Corelli, his Complete Preludes, Op. 23,<br />

and Op. 32, and his Piano Sonata No. 2.<br />

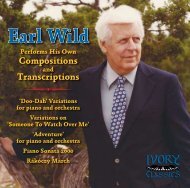

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> is also looking forward to re-releasing Mr. Wild’s own<br />

composition Variations on a Theme of Stephen Foster for Piano and Orchestra<br />

(“Doo-Dah” Variations) originally recorded in 1992. Each of these original<br />

digital recordings will be remastered utilizing the latest 24-bit technology<br />

and will feature new artwork, rare photographs, and insightful liner notes.<br />

Mr. Wild is currently working on his memoirs to be released soon.<br />

Earl Wild’s compositions and transcriptions are published by<br />

Michael Rolland Davis Productions, ASCAP<br />

mrdavisprod@sprintmail.com<br />

Telephone: 614.761.8709<br />

Mr. Wild’s official website: www.EarlWild.com<br />

– 17 –

Earl Wild on <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong><br />

BEETHOVEN (CD - 76001) (DDD)<br />

Stunning performances of ‘Hammerklavier’ & Op. 31, No.3 Sonatas.<br />

NIKOLAI MEDTNER (CD - 75003) (DDD)<br />

Definitive performance of solo piano music by Medtner. Second<br />

improvisation Op. 47; forgotten melodies Op. 39; Sonate-Idylle Op. 56.<br />

LIVING HISTORY (CD - 75002) (DDD)<br />

Bach – Partita No.1; Scriabin – Sonata No.4; Franck – Prelude, Chorale<br />

and Fugue; Schumann - Fantasiestücke Op. 12.<br />

CHOPIN SCHERZOS & BALLADES (CD - 75001) (DDD)<br />

Four Scherzos and Four Ballades.<br />

EARL WILD at 88 (CD - 73005) (DDD)<br />

Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin, Balakirev, Earl Wild<br />

“At 88 Earl Wild’s fabled technique remains staggeringly intact, while his artistry<br />

continues to evolve! When you hear this disc, you'll believe in miracles. Buy it.”<br />

RACHMANINOFF SONG TRANSCRIPTIONS (CD - 74001) (DDD)<br />

“Earl Wild is the finest transcriber of his time.”<br />

Thirteen Rachmaninoff / Wild Song Transcriptions.<br />

– 18 –

Credits<br />

Recorded in Fernleaf Abbey, Columbus, Ohio, June 8-12, 1992<br />

20-bit State-of-the-Art Original recording.<br />

Remastered at 24-bit using the SADiE Artemis<br />

High Resolution digital workstation.<br />

Original and Remastering Producer: Michael Rolland Davis<br />

Original and Remastering Engineer: Ed Thompson<br />

Piano Technician: Paul Schopis - Baldwin Piano<br />

Liner Notes: James E. Frazier<br />

Cover photo of Earl Wild by Richard Pare<br />

Design: Samskara, Inc.<br />

To place an order or to be included on our mailing list:<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® • P.O. Box 341068 • Columbus, Ohio 43234-1068<br />

Phone: 888-40-IVORY or 614-761-8709 • Fax: 614-761-9799<br />

michaeldavis@ivoryclassics.com • For easy and convenient<br />

shopping online, please visit our website: www.<strong>Ivory</strong><strong>Classics</strong>.com<br />

– 19 –