70904 for PDF 11/05 - Ivory Classics

70904 for PDF 11/05 - Ivory Classics

70904 for PDF 11/05 - Ivory Classics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

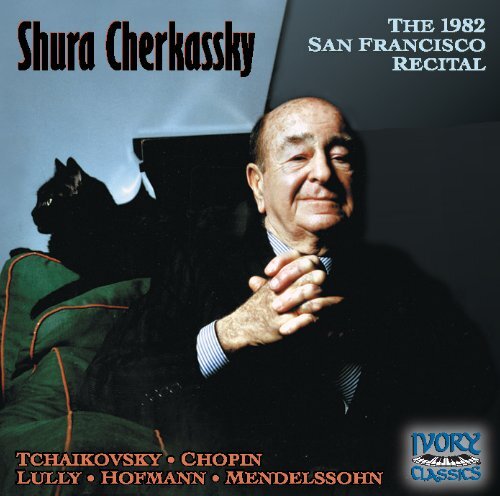

Shura Cherkassky<br />

The 1982 San Francisco Recital<br />

1 - 5 Lully: Suite de pièces<br />

Jean Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), although known as the founder of French grand opera,<br />

was born in Florence, Italy, becoming a naturalized French citizen in 1661. At the age of thirteen<br />

he was taken to France by the Chevalier de Guise, to amuse Mlle. de Montpensier, having<br />

learned to play the violin and guitar from a Franciscan monk. However, he was initially<br />

given kitchen work. It was only when he was heard playing the violin that Lully was promptly<br />

transferred to Mademoiselle’s own orchestra. This was <strong>for</strong> only a short time, <strong>for</strong> he set to<br />

music a satirical poem reflecting on Mlle. de Montpensier, who expelled him from her house.<br />

After studying the harpsichord and composition he obtained a position in the band of Louis<br />

XIV and soon organized another group, which acquired the reputation of being the finest<br />

orchestra in France. By this time Lully was unrivaled as a violinist, and was most solidly in<br />

the favor of the king, writing ballets and masques in which both he and the king took part.<br />

Eventually he was given sole authority to produce operas in France, establishing<br />

an “Academie Royale de Musique” (now the Grand Opera), and the theater of his rival,<br />

Cambert, was closed upon order of the king.<br />

From then on Lully was the dominating power in French music. He not only composed<br />

prolifically, but also created new traditions in theatre discipline; taught singers how to walk<br />

on the stage; invented steps <strong>for</strong> the ballet; changed the entrances, and above all, insisted on a<br />

precision of attack in the orchestra. It has been said that he “more than once broke a violin<br />

on the back of a man who was not playing to his taste, but when the rehearsal was at an end<br />

would send <strong>for</strong> the man, pay him three times the value of his instrument, and take him out<br />

to dine.”<br />

He was an amusing bundle of contradictions. A master of truckling and deceit, he was<br />

sometimes recklessly impudent to those who held power over him. Once, when a mechanical<br />

difficulty caused delay in beginning a per<strong>for</strong>mance of one of his operas which the King was<br />

attending, a message was sent to Lully that the Grand Monarque was tired of waiting. “The<br />

King is master here,” retorted Lully, “and is at liberty to be as tired of waiting as he pleases!”<br />

For fourteen years, as overlord of the Opera, he acted as director, composer, conductor, stagemanager,<br />

ballet-master, and machinist (if electricity had been in use, Lully would have managed<br />

the lights). He did all these things with superlative ability, energy, and resource; yet<br />

– 2 –

this amazing Italian found time to become<br />

(as biographer W. F. Apthorp has pointed<br />

out), “not only the true founder of French<br />

Opera, but to adapt, with surpassing cleverness<br />

and insight into the French character,<br />

what was essentially Italian opera to<br />

the French taste.” From 1658 to 1671, he<br />

wrote about thirty ballets and divertissements,<br />

and between 1672 and 1696,<br />

twenty operas, in addition to instrumental<br />

and church music. He was a master of various<br />

styles, from tragedy to burlesque. He<br />

turned upside down the traditions of the<br />

court ballet. He knew the theatre backwards<br />

and <strong>for</strong>wards. His sense of stage<br />

effect was keen and intuitive; and he knew<br />

a subtler and deeper secret: how to make<br />

music speak with dramatic veracity and<br />

point.<br />

At the end this buffon odieux (as<br />

Boileau called him) – this rake, knave,<br />

intriguer, who had lifted himself out of<br />

Jean Baptiste Lully<br />

the obscurity of his Italian origin into a<br />

position where he talked back to a King, – died of an abscess of the toe. His estate consisted<br />

of fifty-eight sacks of louis d’or and Spanish doubloons, diamonds, and silver plate, worth in<br />

all about seven million francs.<br />

To the very last he was cheerfully unscrupulous, <strong>for</strong> (according to a story told immediately<br />

after his death) he cheated to attain Heaven. His confessor, so runs the familiar tale,<br />

required as a condition that Lully should burn all that he had written of his new opera,<br />

Achille et Polyxène. Lully gave the abhorred score to the confessor, who triumphantly threw<br />

it in the fire. “What, Baptiste!” remonstrated a prince who visited Lully soon after, “you have<br />

destroyed your opera?” “Gently, Sir,” whispered the expiring rascal: “I have another copy.”<br />

So he died, radiant, corrupt, and unashamed, a poet and a genius; and his epitaph in the<br />

– 3 –

Church of Saint-Pères declares that “God gave him. . . a truly Christian patience in the sharp<br />

pain of his last illness.”<br />

The so-called Suite de Pièces was not actually assembled by Lully. Lully’s fame was so great<br />

that his editors often collected his dances and published them as keyboard suites. These transcriptions<br />

from Lully’s operas and ballets were particularly abundant in the nineteenth century<br />

and appeared in editions produced by Théodore Lack and Louis Oesterle. Shura<br />

Cherkassky per<strong>for</strong>med Lully’s Suite de Pièces utilizing as a point of musical departure<br />

Oesterle’s edition published by G. Schirmer in 1904. Cherkassky changes the order of the<br />

pieces, making the suite more cohesive, and adds his own touches of ornamentation in a very<br />

Romantic style.<br />

6 Mendelssohn: Scherzo a Capriccio in F-sharp minor<br />

“Felix” (Latin <strong>for</strong> “the happy one”) was a well-chosen name <strong>for</strong> Mendelssohn, <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Goddess of Fortune gave him her choicest gifts, a diadem of genius <strong>for</strong> his curly head, inherited<br />

wealth from his father, a winning charm of manner and a graceful upright physique. The<br />

frustrations, maladjustments, and conflicts of most great composers make the life of Felix<br />

Mendelssohn as refreshing as sunshine. Born in Hamburg, February 3, 1809, Ludwig Felix<br />

Mendelssohn-Bartholdy was the grandson of the Jewish pragmatic philosopher, Moses<br />

Mendelssohn – known as the “German Plato” – and son of the banker, Abraham<br />

Mendelssohn. His mother Lea Salomon-Bartholdy was his first piano teacher. He studied<br />

with Ludwig Berger (piano), Carl Friedrich Zelter (theory), and Wilhelm Hennig (violin). At<br />

nine he played the piano part of a trio by Wolff in public; at ten he sang alto in the<br />

Singakademie; at eleven he was introduced to Goethe who spoke the highest praises of his<br />

piano-playing and insisted that the wunderkind stay with him in Baden <strong>for</strong> two weeks. At<br />

their first meeting the poet requested he play a Bach fugue, and though he <strong>for</strong>got a part of<br />

the composition, he was able to extemporize the missing portion weaving contrapuntal lines<br />

into a heavy brocaded baroque fabric that pleased all who were present <strong>for</strong> the per<strong>for</strong>mance.<br />

Shortly after Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony came out, Mendelssohn, then 15, could play it all<br />

on the piano without a score. At seventeen he wrote the overture to Shakespeare’s<br />

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Light, aerial music was his unsurpassed speciality.<br />

Between 1827 and 1835, Mendelssohn’s activity took him from city to city on the<br />

Continent and in England. His popularity increased to a point where he was deluged with<br />

invitations to the finest homes. In 1829 he conducted the first per<strong>for</strong>mance, after Bach’s<br />

– 4 –

death, of the great St. Matthew Passion. The<br />

next several years saw the production of many<br />

important works, among which were the first<br />

volume of the Songs Without Words, the<br />

Hebrides Overture, the Italian and<br />

Re<strong>for</strong>mation symphonies and the G minor<br />

Piano Concerto. In 1835, Mendelssohn<br />

became the conductor of the Gewandhaus<br />

Orchestra in Leipzig, and eight years after that<br />

he helped to found the Leipzig Conservatory.<br />

On May 8, 1847 after a grueling concert<br />

schedule in England, taking a rest in Frankfurt<br />

am Main, Mendelssohn was brought word of<br />

his sister Fanny’s untimely death. She had been<br />

rehearsing with a chamber group <strong>for</strong> a per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

in the family home when she suddenly<br />

lost consciousness and died a few hours later.<br />

This was more than Mendelssohn could bear.<br />

He himself fell to the ground unconscious, a<br />

blood vessel in his head ruptured mirroring the<br />

phantom hemorrhage of his beloved Fanny,<br />

Felix Mendelssohn<br />

sharer of his hopes, and an emotional double of<br />

his inner self. There seemed no joy left in the world <strong>for</strong> Mendelssohn from that point on.<br />

Mendelssohn a young man of thirty-eight died of a paralytic stroke on the fourth of November<br />

1847. He was put to rest in the family vault in Berlin.<br />

Mendelssohn probably composed his little-known Scherzo a Capriccio in F-sharp minor in<br />

1835-36. The piece was not given an opus number, but appeared in a collection called Album<br />

des Pianistes, published in Bonn. This highly charged masterpiece is a blend of vitality and<br />

poignancy. The scherzo is built from the alternation of several contrasting themes or segments,<br />

the first light and staccato, the second more legato and expressive, and a third marked<br />

con fuoco (with fire). This and other neglected piano works by Mendelssohn were always<br />

favorites of Shura Cherkassky, who played them since his childhood.<br />

– 5 –

7 - 10 Tchaikovsky:<br />

Grand Sonata in G Major, Op. 37<br />

Piano works composed over a period of<br />

26 years (1867-1893) comprise a by no<br />

means insignificant part of Tchaikovsky’s<br />

chamber music. True, his compositions <strong>for</strong><br />

the piano cannot claim a leading place in his<br />

musical legacy, nevertheless against the<br />

background of the post-Lisztian piano literature<br />

of Western Europe, his works <strong>for</strong> the<br />

piano are distinguished by their variety and<br />

originality. Tchaikovsky was an excellent<br />

pianist from his youth. When he graduated<br />

in 1859 he played Liszt’s extremely difficult<br />

fantasia on theme’s from “Lucia di<br />

Lammermoor,” and when the Moscow<br />

Conservatory opened in 1866 he gave a brilliant<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance of a piano transcription<br />

of the overture to “Russlan and Ludmila.”<br />

His personal tastes in piano music caused<br />

Tchaikovsky to single out Robert<br />

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky<br />

Schumann as his favorite composer <strong>for</strong> the<br />

piano. Schumann’s restless lyricism, the<br />

range of his ideas and even his exposition with its ingenious rhythms exercised a tremendous<br />

influence on Tchaikovsky. Considerable too was the influence of Chopin. On the other<br />

hand, he was indifferent to Liszt’s radical re<strong>for</strong>ms in piano execution, subtle, dazzling virtuosity<br />

and effervescence of design, although he had the greatest respect <strong>for</strong> Liszt as a composer.<br />

It is not difficult to trace these diverse influences in Tchaikovsky’s piano music. As always,<br />

they were transmuted in the crucible of his genius and bore the unmistakable stamp of his<br />

creative individuality. It is this individuality that makes Tchaikovsky’s piano compositions so<br />

difficult to per<strong>for</strong>m: the pianist must project himself into the images expressed in the music<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e he can reveal the profound essence that is sometimes concealed behind some simple<br />

salon dance or elegant concert showpiece.<br />

– 6 –

Tchaikovsky composed only two works he labeled “Sonata” and both were <strong>for</strong> solo piano.<br />

The first, in c-sharp minor, Opus 80, was one of his earliest works of any kind, composed in<br />

1865. Tchaikovsky considered this Sonata a student work and withheld it from publication.<br />

The rather late opus number was affixed at the time of the posthumous publication in 1900.<br />

Tchaikovsky’s second sonata was begun on March 13, 1878, a few days be<strong>for</strong>e he started work<br />

on his celebrated Violin Concerto. Tchaikovsky completed it on August 7th of that year and<br />

it was premiered in Moscow by Nikolai Rubinstein on November 2, 1879.<br />

The “Grand Sonata” (at it is sometimes known) is in G Major and in four movements.<br />

The work is unusually rich in musical ideas. The first movement is built up of measured<br />

march rhythms and impassioned recitatives, giving the impression of a greatly augmented<br />

introduction confined within the sonata framework. The march movement in 3/4 changes to<br />

a recitative theme. Elements of improvisation and drama merge in the solemn phrases of<br />

musical oratory. A passionate restless second theme is contrasted to the calm serenity of the<br />

concluding part. The solemn development is crowned by a tense march in 3/4. The same<br />

march motif predominates in the brilliant coda. The second movement, marked Andante, is<br />

extremely poetic. Its main theme, touched by a sorrowful lyricism, is set off by a number of<br />

whimsical episodes and is somewhat reminiscent of Schumann. The light, un<strong>for</strong>ced Scherzo<br />

might well belong to a Schumann Novellette. The finale, however, is dominated, like the first<br />

movement, by the composer’s preoccupation with constructing a large-scale, elaborate discourse.<br />

The Sonata in G Major, Opus 37 closes on an orchestrally majestic tone.<br />

<strong>11</strong> Chopin: Polonaise Fantaisie in A-flat Major, Op.61 and<br />

13 Chopin: Waltz in A-flat Major, Op.42<br />

Frederic Chopin arrived almost immediately at a personal idiom that is absolutely unmistakable<br />

– an original style so pervasive that a fragmentary bar or two will serve to identify a<br />

composition as his. With a rarer sense of what kingdom he could make his own, he chose to<br />

write music <strong>for</strong> the piano. He never composed an opera or an oratorio, a symphony nor even<br />

a string quartet. These large <strong>for</strong>ms he left to others. He worked in a dozen or more <strong>for</strong>ms, several<br />

of them his own creation. Chopin has left us mazurkas, fresh and narrative; waltzes, prismatic<br />

from his alembic imagination; nocturnes, the perfection of chivalrous dreams; scherzos,<br />

tragic to the heart’s core; preludes, Wordsworthian in simplicity and charm; etudes, complete<br />

as sonnets; impromptus, full of life or touched with tenderest romance; polonaises, the<br />

exquisite expression of the pageantry of his native land; and three sonatas, each a tremen-<br />

– 7 –

Fryderyk Chopin portrait-coin by Antoine Bovy, 1837<br />

dous tragedy. He is a composer par excellence<br />

of inexhaustible variety in infinite<br />

detail.<br />

Chopin’s first published composition,<br />

in 1817 at the age of eight, was a<br />

Polonaise, and in the next five years he<br />

followed that with three more.<br />

Altogether there are sixteen Polonaises<br />

<strong>for</strong> piano solo, although the standard collections<br />

usually contain only eleven, of<br />

which four are posthumous publications.<br />

In addition, there is the Grande<br />

Polonaise, Opus 22 with orchestra<br />

accompaniment, to which Chopin added<br />

an introductory unaccompanied<br />

Andante Spianato. He also wrote the<br />

Polonaise, Opus 3, <strong>for</strong> cello and piano.<br />

The polonaise is a Polish processional<br />

dance in 3/4 time, and moderate in<br />

tempo. According to Grove’s Dictionary,<br />

“the French name dates back to the 17th<br />

century, a period during which three French princesses in succession became consorts of<br />

Polish kings and French customs and the French language were current at the court.” In its<br />

numerous <strong>for</strong>ms the polonaise served both as a peasant dance and <strong>for</strong> court ceremonies. The<br />

Polonaise Fantaisie in A-flat Major, Opus 61, composed in 1845-46, was Chopin’s last largescale<br />

composition <strong>for</strong> the piano. In a letter to his family of December 1845 Chopin, already<br />

seriously ill with tuberculosis, wrote. “I should now like to finish my violoncello sonata, barcarolle<br />

and something else I don’t know how to name.” The title he eventually did provide<br />

demonstrates the work’s hybrid name: rhythms and other elements of the Polonaise are blended<br />

into a very free, almost improvisatory structure. Franz Liszt characterized the work as<br />

“marked with feverish and restless anxiety” and found it dominated by<br />

“a deep sadness, broken constantly by startled movements, by sudden alarms, by disturbed<br />

rest.” Without a doubt it is one of Chopin’s most profound and moving compositions, and<br />

– 8 –

as James Huneker once remarked, “a work that unites the characteristics of superb and original<br />

manipulation of the Polonaise <strong>for</strong>m, the martial and the melancholic.”<br />

During his visit to Vienna, Chopin wrote: “I have acquired nothing particularly Viennese;<br />

and I still cannot play waltzes.” Perhaps he could not play waltzes in the traditional Viennese<br />

ballroom manner, but he certainly could compose dance poems in that <strong>for</strong>m. His waltzes were<br />

probably inspired by Johann Strauss I (the father), whose popularity was at a peak when<br />

Chopin came to Vienna. Some of Chopin’s waltzes are stylized dances and could be suited <strong>for</strong><br />

the ballroom, others, however, are lyric poems in waltz-time, which some biographers have<br />

described as “dances of the soul.” All of them are characterized by aristocratic elegance. The<br />

Waltz in A flat Major, Opus 42 is one of the most beautiful and brilliant of the Chopin<br />

waltzes. By some writers it is acclaimed to depict the Duchess of Richmond’s ball on the eve<br />

of Waterloo, described in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. Robert Schumann, in speaking of it,<br />

regards it as a salon piece of the noblest kind, and if played <strong>for</strong> dancers, states that “half the<br />

ladies should be countesses at least.” Shura Cherkassky plays this work as an encore to his<br />

recital with gusto and panache and a true Romantic sensibility.<br />

12 Hofmann: Kaleidoskop, Op.40, No.4<br />

Josef Casimir Hofmann was born in Cracow, Poland, January 20, 1876. His mother was<br />

a singer. His father, Casimir Hofmann, was professor of harmony and composition at the<br />

Warsaw Conservatory, conductor of the opera, and a composer of operettas. Young Josef studied<br />

the piano with his father. When he was six years old he played in public at a charity concert<br />

in Warsaw. At age nine he gave concerts in Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and<br />

later he played in Vienna, Paris, and London.<br />

He came to the United States in 1887 and made his first appearance in New York on<br />

November 28 of that year. It was a “private recital <strong>for</strong> the press” given at Wallack’s Theatre,<br />

“be<strong>for</strong>e a representative gathering of literary, musical, and dramatic people to the number of<br />

200, when the new world heard <strong>for</strong> the first time the piano played in the most masterly manner<br />

by a child only a few months over ten years old” thus Henry Krehbiel in the New York<br />

Tribune of the day after. “The audience,” Krehbiel wrote, “saw a pleasant and robust looking<br />

boy, dressed in dark gray jacket and pair of knickerbockers, and with an enormous sailor<br />

collar to his shirt, reaching halfway down his back. He acknowledged with perfect ease and<br />

self-possession the applause that greeted him, and took his seat at one piano, his father at<br />

another. The first number was the Variations by Saint-Saëns on a Theme by Beethoven, <strong>for</strong><br />

– 9 –

two pianos. . . . The audience listened at first<br />

in amazement, then in admiration, and at<br />

last surrendered themselves to a feeling of<br />

affectionate regard <strong>for</strong> the Heaven-gifted<br />

genius. While he played, Hofmann ceased to<br />

be a boy. The soul of a man, and to a great<br />

extent, a man’s power, seemed to have passed<br />

into him.”<br />

Hofmann’s first appearance in public was<br />

on the following day, at the Metropolitan<br />

Opera House – a concert “unique in the history<br />

of New York,” according to Henry<br />

Krehbiel. His program included Beethoven’s<br />

First Concerto, a “theme and variations” by<br />

Rameau, a Berceuse and Waltz composed by<br />

himself; a Chopin Waltz and Nocturne, and<br />

the Weber-Liszt Polacca <strong>for</strong> piano and<br />

orchestra. Mr. Krehbiel doubted “if the feats<br />

of Liszt in his prodigy years could have been<br />

more amazing. ... There can be no talk of real<br />

depth of feeling in such a case, but the taste<br />

of the lad is exquisite, his command of tonecolor<br />

amazing, his reposefulness of delivery<br />

Josef Hofmann<br />

would reflect credit on any other artist, his<br />

sense of symmetry is most delightful, and his<br />

digital agility as great as that which the majority of piano players attain after practicing as<br />

many years as this little lad has lived.”<br />

In the course of his first American tour, young Hofmann gave fifty-two concerts in two<br />

months and a half, thereby attracting the notice of the Society <strong>for</strong> the Prevention of Cruelty<br />

to Children. The boy was rescued from exploitation, and was withdrawn from the public plat<strong>for</strong>m<br />

<strong>for</strong> his own good, largely through the generosity and public spirit of the late Alfred<br />

Corning Clark. He returned to Europe with his father, studied at Berlin with Urban and<br />

Moszkowski, and in 1892 became a pupil of Anton Rubinstein, with whom he studied <strong>for</strong><br />

– 10 –

two and a half years. In 1894 he reappeared in public at Dresden, and in 1897 began another<br />

concert tour of Europe and America. When he resumed his concert career he was almost<br />

universally acclaimed as one of the most astounding keyboard artists of all time. His extraordinary<br />

success was due in part to a breathtaking technical wizardry that has probably never<br />

been surpassed, but equally to an incredibly sensitive control of tone and other pianistic<br />

resources of musical variety. In 1937 Hofmann celebrated his golden jubilee with a concert<br />

at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. His final public appearance was at<br />

Carnegie Hall on January 16, 1946. Hofmann made his home <strong>for</strong> the most part in Aiken,<br />

South Carolina. In addition to his concert career, he was also a prolific composer, and a very<br />

sucessful inventor, with more than 60 patents to his credit. From 1926 until 1938 he was<br />

head of the Curtis Institute of Music, where one of his most gifted students was Shura<br />

Cherkassky.<br />

Hofmann wrote over 100 compositions. Kaleidoskop was published by Julius Heinrich<br />

Zimmermann Verlag in 1908 as part of a set of four Charakterskizzen für Klavier, Opus 40<br />

(the other three were titled: Vision, Jadis, and Nenien). Hofmann dedicated these four pieces<br />

to the pianist, Leopold Godowsky. A kaleidoscope is an optical instrument, invented in 1816<br />

by Sir David Brewster. In the 19th century kaleidoscopes eventually became very popular<br />

toys. Most kaleidoscopes consist of a cylindrical tube through a length of which pass two<br />

reflecting planes touching along one edge to <strong>for</strong>m two sides of a triangular prism. One end<br />

of the tube is fitted with an eyepiece, the other is closed by two circular pieces of glass (the<br />

outer frosted, the inner clear) between which are loose fragments of colored glass or other colorful<br />

objects. As the tube is rotated, the colorful bits and pieces fall into a variety of patterns<br />

multiplied by reflection. Hofmann’s Kaleidoskop is a pianistic version of the popular optical<br />

toy, where the piano notes tumble in the cylinder, creating a cornucopia of musical reflections<br />

and refractions. In Shura Cherkassky’s authoritative interpretation, Kaleidoskop dazzles us<br />

with its shimmering colors!<br />

– <strong>11</strong> –

Shura Cherkassky<br />

– 12 –

Shura Cherkassky (19<strong>11</strong>-1995)<br />

Born in Odessa on October 17, 19<strong>11</strong>, Shura Cherkassky was among the last of the post-<br />

Romantic tradition of master pianists. During his youth, he immigrated to Baltimore, and<br />

studied in Philadelphia with the renowned Josef Hofmann, a pupil of Anton Rubinstein. His<br />

debut concert tour in 1923 included appearances with Walter Damrosch and the New York<br />

Symphony and a command per<strong>for</strong>mance at The White House <strong>for</strong> President Warren G.<br />

Harding.<br />

Shura Cherkassky’s enormous popularity in Germany and Austria sprang from his first<br />

major European tour in 1946, when a concert in Hamburg established him as one of the leading<br />

pianists of the day. All over Europe Cherkassky had his following of enthusiastic admirers,<br />

from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. He regularly per<strong>for</strong>med at the prestigious music<br />

festivals of Europe, including those of London, Salzburg, Bergen, Zagreb, Carinthia and<br />

Vienna, and had collaborated with some of the world’s most distinguished conductors:<br />

Comissiona, Dorati, Giulini, Haitink, Karajan, Kempe, Leinsdorf, Ormandy, Shostakovich,<br />

Sir Adrian Boult, Sir Charles Groves and Sir Georg Solti.<br />

Shura Cherkassky’s concert career encompassed the entire musical world. In addition to<br />

Europe, he made several tours throughout the Far East, including China, Hong Kong,<br />

Singapore, Thailand, and Japan. He also toured Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and<br />

India. His triumphant return to his native Russia in 1976 had great emotional significance<br />

<strong>for</strong> him, and he was re-invited <strong>for</strong> subsequent tours in 1977 and 1979.<br />

Early in 1976 Shura Cherkassky returned to the United States after an absence of ten<br />

years. His New York recital was received with such resounding acclaim that he devoted an<br />

important part of each season to North America. An international artist might be expected to<br />

remain stationary during his holidays, but not Cherkassky. His passion <strong>for</strong> constant travel<br />

took him to Afghanistan, Thailand, Israel, Egypt, the Greek Islands, the African Coast,<br />

Northern Europe, the South Pacific, Latin and South America, Siberia and China.<br />

Shura Cherkassky, died in London, on December 27, 1995. Writing in Gramophone,<br />

music critic and long-time friend, Bryce Morrison stated: “Few, if any pianists, have made<br />

music so entirely their own, coloring and projecting every bar and note with an instantly recognizable<br />

zest and brio. Rejoicing in spontaneity and listening askance to younger colleagues<br />

with set and inflexible ideas, he could turn a work – whether a Beethoven sonata, a Chopin<br />

Scherzo, a contemporary offering or a delectable trifle from a bygone age by Rebikov or<br />

– 13 –

Albéniz-Godowsky – this way and that, reflecting<br />

its contours and tints as if through some<br />

revolving prism. . . . Musically speaking he was<br />

one of life’s great adventurers, tirelessly seeking<br />

out novel angles, nooks and crannies, deploying<br />

a heaven-sent cantabile (“Nobody seems to care<br />

about sound any more,” Cherkassky once<br />

lamented) and, at his greatest, complementing<br />

his plethora of ideas with a rich and transcendental<br />

pianism.”<br />

“We were <strong>for</strong>tunate to meet Shura<br />

Cherkassky in 1978 when he per<strong>for</strong>med in<br />

Berkeley, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia,” write producers Marina<br />

and Victor Ledin. “He per<strong>for</strong>med a program of<br />

Schumann, Bartok, Chopin, and Mussorgsky...<br />

and after the concert we went <strong>for</strong> a frozen yogurt<br />

treat.” “He granted us permission in 1982 to<br />

record his San Francisco recital, which was<br />

broadcast on public radio. He remarked to us at<br />

that time that all of the compositions he was<br />

about to play felt fresh to him... Not one to ever<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

play any piece of music twice the same way, he<br />

on several occasions told us that these San<br />

Francisco per<strong>for</strong>mances were among his favorite interpretations. For those who were not <strong>for</strong>tunate<br />

enough to have experienced a live Cherkassky concert per<strong>for</strong>mance, we hope that this<br />

recording will prove as musically enriching as it was <strong>for</strong> us.”<br />

Over his long career, Shura Cherkassky recorded <strong>for</strong> London/Decca, Nimbus, Vox,<br />

Deutsche Grammophon, L’Oiseau-Lyre, Reader’s Digest, HMV, Concert Hall Society, Cupol,<br />

Columbia, RCA Victor and Tudor.<br />

– 14 –

Credits<br />

Digitally recorded in concert on April 18, 1982 at Davies Symphony Hall,<br />

San Francisco, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<br />

Producers: Marina and Victor Ledin<br />

Recording Engineer: Jack Vad<br />

Remastering Producer: Michael Rolland Davis<br />

Remastering Engineer: Ed Thompson<br />

Thanks to Ms. Christa Phelps and the Cherkassky Estate<br />

Liner Notes: Marina and Victor Ledin<br />

Design: Communication Graphics<br />

Cover Photograph: Shura Cherkassky, May 1993, by Malcolm Crowthers<br />

Inside Tray Photo: Shura Cherkassky, June 1994<br />

Interior Photos: Shura Cherkassky (Pages 12 and 14) by Clive Barda<br />

To place an order or to be included on mailing list:<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> <br />

P.O. Box 341068 • Columbus, Ohio 43234-1068<br />

Phone: 888-40-IVORY or 614-761-8709 • Fax: 614-761-9799<br />

e-mail@ivoryclassics.com • Website: http://www.<strong>Ivory</strong><strong>Classics</strong>.com<br />

– 15 –

Shura Cherkassky<br />

Shura Cherkassky<br />

THE 1982 SAN FRANCISCO RECITAL<br />

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Suite de pièces 12:39<br />

1 Allemande 2:32<br />

2 Air tendre 2:52<br />

3 Courante 1:56<br />

4 Sarabande 2:40<br />

5 Gigue 2:39<br />

Felix Mendelssohn: Scherzo a Capriccio<br />

in F-sharp minor (1835-6)<br />

6 Presto scherzando 6:26<br />

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: Grand Sonata<br />

in G Major, Opus 37 32:43<br />

7 I. Moderato e risoluto 13:10<br />

8 II. Andante non troppo quasi<br />

moderato; Moderato con animazione 9:56<br />

9<br />

10<br />

III. Scherzo: Allegro giocoso 2:38<br />

IV. Finale: Allegro vivace 6:59<br />

Fryderyk Chopin:<br />

Polonaise Fantaisie in A-flat Major, Op.61<br />

<strong>11</strong> Allegro maestoso <strong>11</strong>:50<br />

Josef Hofmann:<br />

Kaleidoskop, Op. 40, No.4<br />

12 Presto 4:55<br />

Fryderyk Chopin:<br />

Waltz in A-flat Major, Op.42<br />

13 Vivace 3:47<br />

Total Playing Time: 72:43<br />

Remastering Producer: Michael Rolland Davis • Remastering Engineer: Ed Thompson<br />

Recorded in Concert on April 18, 1982 at Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<br />

1999 <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> • All Rights Reserved.<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> • P.O. Box 341068<br />

Columbus, Ohio 43234-1068 U.S.A.<br />

Phone: 888-40-IVORY or 614-761-8709 • Fax: 614-761-9799<br />

e-mail@ivoryclassics.com • Website: www.<strong>Ivory</strong><strong>Classics</strong>.com<br />

STEREO<br />

644<strong>05</strong>-<strong>70904</strong><br />

®