Torah from JTS Bo 5770

Torah from JTS Bo 5770

Torah from JTS Bo 5770

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ב' '<br />

ב''<br />

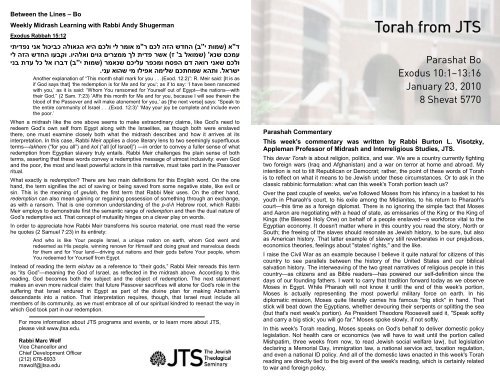

Between the Lines – <strong>Bo</strong><br />

Weekly Midrash Learning with Rabbi Andy Shugerman<br />

Exodus Rabbah 15:12<br />

ד"א (שמות י ( החדש הזה לכם ר"מ אומר לי ולכם היא ה ג א ו ל ה כ ב י כ ו ל א נ י נ פ ד י ת י<br />

ע מ כ ם ש נ א' (ש מ ו א ל ב' ז) א ש ר פ ד י ת ל ך מ מ צ ר י ם ג ו י ם ו א ל ה י ו. ו ק ב ע ו ה ח ד ש ה ז ה ל י<br />

ו ל כ ם ש א נ י ר ו א ה ד ם ה פ ס ח ו מ כ פ ר ע ל י כ ם ש נ א מ ר (ש מ ו ת י ד ב ר ו א ל כ ל ע ד ת ב נ י<br />

ישראל. ותהא שמחתכם שלימה אפילו מי שהוא עני.<br />

(<br />

Another explanation of “This month shall mark for you . . .(Exod. 12:2)”: R. Meir said: [It is as<br />

if God says that] ‘the redemption is for Me and for you’; as if to say: ‘I have been ransomed<br />

with you,’ as it is said: “Whom You ransomed for Yourself out of Egypt—the nations—with<br />

their God.” (2 Sam. 7:23) ‘Affix this month for Me and for you, because I will see therein the<br />

blood of the Passover and will make atonement for you,’ as [the next verse] says: “Speak to<br />

the entire community of Israel . . .(Exod. 12:3)” ‘May your joy be complete and include even<br />

the poor.’<br />

When a midrash like the one above seems to make extraordinary claims, like God’s need to<br />

redeem God’s own self <strong>from</strong> Egypt along with the Israelites, as though both were enslaved<br />

there, one must examine closely both what the midrash describes and how it arrives at its<br />

interpretation. In this case, Rabbi Meir applies a close literary lens to two seemingly superfluous<br />

terms—lakhem (“for you all”) and kol (“all [of Israel]”) —in order to convey a fuller sense of what<br />

redemption <strong>from</strong> Egyptian slavery truly entails. Rabbi Meir challenges the plain sense of both<br />

terms, asserting that these words convey a redemptive message of utmost inclusivity: even God<br />

and the poor, the most and least powerful actors in this narrative, must take part in the Passover<br />

ritual.<br />

What exactly is redemption? There are two main definitions for this English word. On the one<br />

hand, the term signifies the act of saving or being saved <strong>from</strong> some negative state, like evil or<br />

sin. This is the meaning of geulah, the first term that Rabbi Meir uses. On the other hand,<br />

redemption can also mean gaining or regaining possession of something through an exchange,<br />

as with a ransom. That is one common understanding of the p-d-h Hebrew root, which Rabbi<br />

Meir employs to demonstrate first the semantic range of redemption and then the dual nature of<br />

God’s redemptive act. That concept of mutuality hinges on a clever play on words.<br />

In order to appreciate how Rabbi Meir transforms his source material, one must read the verse<br />

he quotes (2 Samuel 7:23) in its entirety:<br />

And who is like Your people Israel, a unique nation on earth, whom God went and<br />

redeemed as His people, winning renown for Himself and doing great and marvelous deeds<br />

for them and for Your land—driving out nations and their gods before Your people, whom<br />

You redeemed for Yourself <strong>from</strong> Egypt.<br />

Instead of reading the term elohav as a reference to “their gods,” Rabbi Meir rereads this term<br />

as “its God”—meaning the God of Israel, as reflected in the midrash above. According to this<br />

reading, God becomes both the subject and the object of redemption. The next statement<br />

makes an even more radical claim: that future Passover sacrifices will atone for God's role in the<br />

suffering that Israel endured in Egypt as part of the divine plan for making Abraham’s<br />

descendants into a nation. That interpretation requires, though, that Israel must include all<br />

members of its community, as we must embrace all of our spiritual kindred to reenact the way in<br />

which God took part in our redemption.<br />

For more information about <strong>JTS</strong> programs and events, or to learn more about <strong>JTS</strong>,<br />

please visit www.jtsa.edu.<br />

Rabbi Marc Wolf<br />

Vice Chancellor and<br />

Chief Development Officer<br />

(212) 678-8933<br />

mawolf@jtsa.edu<br />

<strong>Torah</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>JTS</strong><br />

Parashat <strong>Bo</strong><br />

Exodus 10:1–13:16<br />

January 23, 2010<br />

8 Shevat <strong>5770</strong><br />

Parashah Commentary<br />

This week's commentary was written by Rabbi Burton L. Visotzky,<br />

Appleman Professor of Midrash and Interreligious Studies, <strong>JTS</strong>.<br />

This devar <strong>Torah</strong> is about religion, politics, and war. We are a country currently fighting<br />

two foreign wars (Iraq and Afghanistan) and a war on terror at home and abroad. My<br />

intention is not to tilt Republican or Democrat; rather, the point of these words of <strong>Torah</strong><br />

is to reflect on what it means to be Jewish under these circumstances. Or to ask in the<br />

classic rabbinic formulation: what can this week's <strong>Torah</strong> portion teach us?<br />

Over the past couple of weeks, we've followed Moses <strong>from</strong> his infancy in a basket to his<br />

youth in Pharaoh's court, to his exile among the Midianites, to his return to Pharaoh's<br />

court—this time as a foreign diplomat. There is no ignoring the simple fact that Moses<br />

and Aaron are negotiating with a head of state, as emissaries of the King or the King of<br />

Kings (the Blessed Holy One) on behalf of a people enslaved—a workforce vital to the<br />

Egyptian economy. It doesn't matter where in this country you read the story, North or<br />

South; the freeing of the slaves should resonate as Jewish history, to be sure, but also<br />

as American history. That latter example of slavery still reverberates in our prejudices,<br />

economics theories, feelings about "states' rights," and the like.<br />

I raise the Civil War as an example because I believe it quite natural for citizens of this<br />

country to see parallels between the history of the United States and our biblical<br />

salvation history. The interweaving of the two great narratives of religious people in this<br />

country—as citizens and as Bible readers—has powered our self-definition since the<br />

days of our founding fathers. I want to carry that tradition forward today as we observe<br />

Moses in Egypt. While Pharaoh will not know it until the end of this week's portion,<br />

Moses is actually representing the most powerful military force on earth. In his<br />

diplomatic mission, Moses quite literally carries his famous "big stick" in hand. That<br />

stick will beat down the Egyptians, whether devouring their serpents or splitting the sea<br />

(but that's next week's portion). As President Theodore Roosevelt said it, "Speak softly<br />

and carry a big stick; you will go far." Moses spoke slowly, if not softly.<br />

In this week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading, Moses speaks on God's behalf to deliver domestic policy<br />

legislation. Not health care or economics (we will have to wait until the portion called<br />

Mishpatim, three weeks <strong>from</strong> now, to read Jewish social welfare law), but legislation<br />

declaring a Memorial Day, immigration law, a national service act, taxation regulation,<br />

and even a national ID policy. And all of the domestic laws enacted in this week's <strong>Torah</strong><br />

reading are directly tied to the big event of the week's reading, which is certainly related<br />

to war and foreign policy.

Let me unpack these generalizations a bit. The war is God's war on Pharaoh and the<br />

Egyptians in order to free the Jews <strong>from</strong> enslavement. We begin our <strong>Torah</strong> reading in<br />

the middle of the battle, seven plagues already having been unleashed last week. Many<br />

rabbinic midrashim liken the plagues to the tactical weapons of the Roman (or later,<br />

Christian or Muslim) armies. If we are not yet clear that this is war Moses is engaged in,<br />

next week during the Song of the Sea we will sing, "Adonai is a Warrior."<br />

The social policies I mentioned are <strong>from</strong> this week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading: Memorial Day is, in<br />

fact, Passover. Exodus 12:14 commands, "This day shall be a memorial, you shall<br />

celebrate it as a festival to Adonai throughout your generations." As for those other<br />

domestic laws mentioned above, let's review: Immigration policy might be seen in<br />

Exodus 12:49: "There shall be one law for the citizen and for the stranger who dwells<br />

among you." National service? Read Exodus 13:1: "Consecrate to Me the firstborn of<br />

every womb among the Israelites; whether of man or of beast, they are Mine." Our<br />

rabbis teach us that before there was priesthood (kohanim) the firstborn were drafted<br />

into God's service. To this day we observe the custom of redeeming the firstborn child<br />

<strong>from</strong> that service (pidyon haben). There actually was a time in US history when one<br />

could pay to be redeemed <strong>from</strong> military service; Michael Sandel has an illuminating<br />

discussion of the ethics of the practice in his recent book Justice: What's the Right<br />

Thing to Do?<br />

Taxes are right there in the same passage. God not only claims service <strong>from</strong> firstborn<br />

children, God taxes the Israelites their firstborn cattle. Later, we'll see that the Israelites'<br />

crops are taxed as well: first fruits and grains for God, gleanings and leavings of the<br />

field for God's poor. Let's not forget the commandment for a Jewish ID system. No, I'm<br />

not talking about circumcision (even though it's mentioned in this week's portion at<br />

Exodus 12:43–48), primarily because that particular Jewish marking is usually not<br />

visible. But the portion commands that we Jews mark our doorposts (mezuzah) at<br />

Exodus 12:24; and wear tefillin (in the final verse of this week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading).<br />

I freely admit that all of these rituals don't sound like domestic policy regulation to us,<br />

but they certainly did to the fledgling nation of Israel. With our American ethos of the<br />

separation of church and state (which is a very good thing); we often fail to see how our<br />

ancestors imagined politics and religion to be two complementary manifestations of<br />

national identity-as do most other nations of the world today. Which brings me back to<br />

war, foreign policy, and what the <strong>Torah</strong> may teach us.<br />

Diplomacy (speaking softly) carries little sway without a willingness to wield the big<br />

stick. Moses has no success with Pharaoh through moral suasion. Pharaoh is disdainful<br />

of God, and of Moses and the Israelites, until the plagues start raining down upon him.<br />

Only God's big stick gives Moses the ability to bargain with Pharaoh. As in the case of<br />

Pharaoh and others after him—we cannot read this story without hearing the words of<br />

the Passover Haggadah, "in every generation they rose up against us to destroy us"—<br />

there were times in Jewish history when military might was called for to ensure the<br />

survival of the Jewish people.<br />

But the <strong>Torah</strong> also teaches us that diplomacy must also be part of our national<br />

narrative. In Deuteronomy 20:10–12, God commands that we always first offer terms of<br />

peace. Only if peace is rejected by an overt act of war may we take up arms against our<br />

enemies. This commandment gave rise to "just war" theory, which has been pursued by<br />

governments <strong>from</strong> the time of Maimonides to our current American administration.<br />

Soon we will gather around our televisions for that rite we call the State of the Union. It<br />

is our obligation as Americans to listen with care to what our president reports, whether<br />

we agree or disagree. This week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading teaches us also to listen as Jews.<br />

The publication and distribution of the <strong>JTS</strong> Commentary are made possible by a generous grant<br />

<strong>from</strong> Rita Dee and Harold (z”l) Hassenfeld.<br />

Taste of <strong>Torah</strong><br />

A Comment on Ramban by Rabbi Matthew Berkowitz<br />

Exodus 12:1–2 The Lord said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt: this<br />

month will mark for you the beginning of the months; it will be the first of the<br />

months of the year for you.<br />

Ramban, “this month will mark for you the beginning of the months,” This<br />

order of the counting of the months is not in regard to the years, for the beginning<br />

of our years is <strong>from</strong> Tishrei, the seventh month . . . If so, when we call the month<br />

of Nisan the first of the months and Tishrei the seventh, the meaning is “the first<br />

month of the redemption” and “the seventh month <strong>from</strong> the redemption.” This is<br />

the meaning of the expression “it will be the first of the months of the year for<br />

you,” meaning that it is not the first in regard to the year but it is the first “for you”;<br />

in other words, it is called “the first” for the purpose of remembering our<br />

redemption.<br />

The first of Tishrei, commonly known as Rosh Hashanah, is celebrated in the<br />

Jewish community as the “official” New Year. Parashat <strong>Bo</strong>, however, undermines<br />

this traditional understanding. At the beginning of Exodus 12, God speaks to<br />

Moses and Aaron and declares that the month of Nisan, in which Passover<br />

occurs, “will mark for you the beginning of the months.” And if that weren’t enough<br />

to confuse us, the Mishnah teaches, not only are there two New Years, but there<br />

are actually four. Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 1:1 explains that the first of Nisan is<br />

the New Year for kings and festivals; the first of Elul is the New Year for tithing of<br />

animals; the first of Tishrei is the New Year for years; and the fifteenth of Shevat<br />

(coming up) is the New Year for trees. How do we reconcile the <strong>Torah</strong>’s teaching<br />

of Nisan as the beginning of the biblical year with the common understanding of<br />

Rosh Hashanah, Tishrei, as the start of the annual cycle?<br />

Ramban contends that in order to understand the biblical commandment, which is<br />

the first given to the Israelite nation, emphasis must be placed on lakhem (for<br />

you). Ramban, sensitively, explains that Nisan represents the first month in<br />

celebration of the Israelite redemption <strong>from</strong> Egypt. It is a month that marks the<br />

beginning of the year for the Jewish people as it marks the pivotal event of yetziat<br />

Mitzrayim. And so, it is the beginning of the counting of the years for you. In other<br />

words, <strong>Torah</strong> recognizes Nisan as the particular new year of the Jewish people<br />

throughout the generations. Nisan is bound intimately with the Israelite transition<br />

<strong>from</strong> slavery to redemption. If Nisan is so central to Jewish identity, why then do<br />

we need Rosh Hashanah?<br />

Nisan and Tishrei represent the poles of the particular and the universal. As<br />

Ramban explains, Nisan is “for you”: it is for the Jewish people in recognition of<br />

their freedom. Tishrei, or Rosh Hashanah, celebrates the birth of the world and<br />

God’s Kingship—clearly more universal in scope. It is between these two poles<br />

that the modern Jew maneuvers—taking to heart the experience of redemption<br />

while seeing oneself as part and parcel of humanity.<br />

With wishes for a good week and Shabbat Shalom.<br />

The publication and distribution of A Taste of <strong>Torah</strong> are made possible by a generous grant <strong>from</strong><br />

Sam and Marilee Susi.