Torah from JTS Bo 5770

Torah from JTS Bo 5770

Torah from JTS Bo 5770

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ב' '<br />

ב''<br />

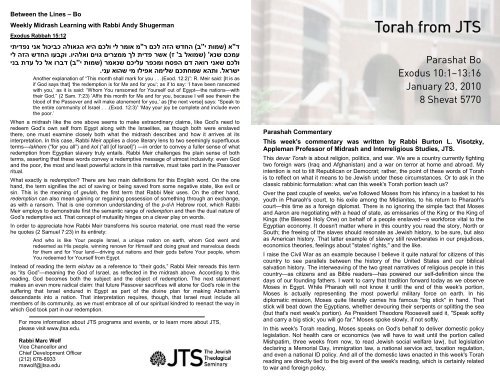

Between the Lines – <strong>Bo</strong><br />

Weekly Midrash Learning with Rabbi Andy Shugerman<br />

Exodus Rabbah 15:12<br />

ד"א (שמות י ( החדש הזה לכם ר"מ אומר לי ולכם היא ה ג א ו ל ה כ ב י כ ו ל א נ י נ פ ד י ת י<br />

ע מ כ ם ש נ א' (ש מ ו א ל ב' ז) א ש ר פ ד י ת ל ך מ מ צ ר י ם ג ו י ם ו א ל ה י ו. ו ק ב ע ו ה ח ד ש ה ז ה ל י<br />

ו ל כ ם ש א נ י ר ו א ה ד ם ה פ ס ח ו מ כ פ ר ע ל י כ ם ש נ א מ ר (ש מ ו ת י ד ב ר ו א ל כ ל ע ד ת ב נ י<br />

ישראל. ותהא שמחתכם שלימה אפילו מי שהוא עני.<br />

(<br />

Another explanation of “This month shall mark for you . . .(Exod. 12:2)”: R. Meir said: [It is as<br />

if God says that] ‘the redemption is for Me and for you’; as if to say: ‘I have been ransomed<br />

with you,’ as it is said: “Whom You ransomed for Yourself out of Egypt—the nations—with<br />

their God.” (2 Sam. 7:23) ‘Affix this month for Me and for you, because I will see therein the<br />

blood of the Passover and will make atonement for you,’ as [the next verse] says: “Speak to<br />

the entire community of Israel . . .(Exod. 12:3)” ‘May your joy be complete and include even<br />

the poor.’<br />

When a midrash like the one above seems to make extraordinary claims, like God’s need to<br />

redeem God’s own self <strong>from</strong> Egypt along with the Israelites, as though both were enslaved<br />

there, one must examine closely both what the midrash describes and how it arrives at its<br />

interpretation. In this case, Rabbi Meir applies a close literary lens to two seemingly superfluous<br />

terms—lakhem (“for you all”) and kol (“all [of Israel]”) —in order to convey a fuller sense of what<br />

redemption <strong>from</strong> Egyptian slavery truly entails. Rabbi Meir challenges the plain sense of both<br />

terms, asserting that these words convey a redemptive message of utmost inclusivity: even God<br />

and the poor, the most and least powerful actors in this narrative, must take part in the Passover<br />

ritual.<br />

What exactly is redemption? There are two main definitions for this English word. On the one<br />

hand, the term signifies the act of saving or being saved <strong>from</strong> some negative state, like evil or<br />

sin. This is the meaning of geulah, the first term that Rabbi Meir uses. On the other hand,<br />

redemption can also mean gaining or regaining possession of something through an exchange,<br />

as with a ransom. That is one common understanding of the p-d-h Hebrew root, which Rabbi<br />

Meir employs to demonstrate first the semantic range of redemption and then the dual nature of<br />

God’s redemptive act. That concept of mutuality hinges on a clever play on words.<br />

In order to appreciate how Rabbi Meir transforms his source material, one must read the verse<br />

he quotes (2 Samuel 7:23) in its entirety:<br />

And who is like Your people Israel, a unique nation on earth, whom God went and<br />

redeemed as His people, winning renown for Himself and doing great and marvelous deeds<br />

for them and for Your land—driving out nations and their gods before Your people, whom<br />

You redeemed for Yourself <strong>from</strong> Egypt.<br />

Instead of reading the term elohav as a reference to “their gods,” Rabbi Meir rereads this term<br />

as “its God”—meaning the God of Israel, as reflected in the midrash above. According to this<br />

reading, God becomes both the subject and the object of redemption. The next statement<br />

makes an even more radical claim: that future Passover sacrifices will atone for God's role in the<br />

suffering that Israel endured in Egypt as part of the divine plan for making Abraham’s<br />

descendants into a nation. That interpretation requires, though, that Israel must include all<br />

members of its community, as we must embrace all of our spiritual kindred to reenact the way in<br />

which God took part in our redemption.<br />

For more information about <strong>JTS</strong> programs and events, or to learn more about <strong>JTS</strong>,<br />

please visit www.jtsa.edu.<br />

Rabbi Marc Wolf<br />

Vice Chancellor and<br />

Chief Development Officer<br />

(212) 678-8933<br />

mawolf@jtsa.edu<br />

<strong>Torah</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>JTS</strong><br />

Parashat <strong>Bo</strong><br />

Exodus 10:1–13:16<br />

January 23, 2010<br />

8 Shevat <strong>5770</strong><br />

Parashah Commentary<br />

This week's commentary was written by Rabbi Burton L. Visotzky,<br />

Appleman Professor of Midrash and Interreligious Studies, <strong>JTS</strong>.<br />

This devar <strong>Torah</strong> is about religion, politics, and war. We are a country currently fighting<br />

two foreign wars (Iraq and Afghanistan) and a war on terror at home and abroad. My<br />

intention is not to tilt Republican or Democrat; rather, the point of these words of <strong>Torah</strong><br />

is to reflect on what it means to be Jewish under these circumstances. Or to ask in the<br />

classic rabbinic formulation: what can this week's <strong>Torah</strong> portion teach us?<br />

Over the past couple of weeks, we've followed Moses <strong>from</strong> his infancy in a basket to his<br />

youth in Pharaoh's court, to his exile among the Midianites, to his return to Pharaoh's<br />

court—this time as a foreign diplomat. There is no ignoring the simple fact that Moses<br />

and Aaron are negotiating with a head of state, as emissaries of the King or the King of<br />

Kings (the Blessed Holy One) on behalf of a people enslaved—a workforce vital to the<br />

Egyptian economy. It doesn't matter where in this country you read the story, North or<br />

South; the freeing of the slaves should resonate as Jewish history, to be sure, but also<br />

as American history. That latter example of slavery still reverberates in our prejudices,<br />

economics theories, feelings about "states' rights," and the like.<br />

I raise the Civil War as an example because I believe it quite natural for citizens of this<br />

country to see parallels between the history of the United States and our biblical<br />

salvation history. The interweaving of the two great narratives of religious people in this<br />

country—as citizens and as Bible readers—has powered our self-definition since the<br />

days of our founding fathers. I want to carry that tradition forward today as we observe<br />

Moses in Egypt. While Pharaoh will not know it until the end of this week's portion,<br />

Moses is actually representing the most powerful military force on earth. In his<br />

diplomatic mission, Moses quite literally carries his famous "big stick" in hand. That<br />

stick will beat down the Egyptians, whether devouring their serpents or splitting the sea<br />

(but that's next week's portion). As President Theodore Roosevelt said it, "Speak softly<br />

and carry a big stick; you will go far." Moses spoke slowly, if not softly.<br />

In this week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading, Moses speaks on God's behalf to deliver domestic policy<br />

legislation. Not health care or economics (we will have to wait until the portion called<br />

Mishpatim, three weeks <strong>from</strong> now, to read Jewish social welfare law), but legislation<br />

declaring a Memorial Day, immigration law, a national service act, taxation regulation,<br />

and even a national ID policy. And all of the domestic laws enacted in this week's <strong>Torah</strong><br />

reading are directly tied to the big event of the week's reading, which is certainly related<br />

to war and foreign policy.

Let me unpack these generalizations a bit. The war is God's war on Pharaoh and the<br />

Egyptians in order to free the Jews <strong>from</strong> enslavement. We begin our <strong>Torah</strong> reading in<br />

the middle of the battle, seven plagues already having been unleashed last week. Many<br />

rabbinic midrashim liken the plagues to the tactical weapons of the Roman (or later,<br />

Christian or Muslim) armies. If we are not yet clear that this is war Moses is engaged in,<br />

next week during the Song of the Sea we will sing, "Adonai is a Warrior."<br />

The social policies I mentioned are <strong>from</strong> this week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading: Memorial Day is, in<br />

fact, Passover. Exodus 12:14 commands, "This day shall be a memorial, you shall<br />

celebrate it as a festival to Adonai throughout your generations." As for those other<br />

domestic laws mentioned above, let's review: Immigration policy might be seen in<br />

Exodus 12:49: "There shall be one law for the citizen and for the stranger who dwells<br />

among you." National service? Read Exodus 13:1: "Consecrate to Me the firstborn of<br />

every womb among the Israelites; whether of man or of beast, they are Mine." Our<br />

rabbis teach us that before there was priesthood (kohanim) the firstborn were drafted<br />

into God's service. To this day we observe the custom of redeeming the firstborn child<br />

<strong>from</strong> that service (pidyon haben). There actually was a time in US history when one<br />

could pay to be redeemed <strong>from</strong> military service; Michael Sandel has an illuminating<br />

discussion of the ethics of the practice in his recent book Justice: What's the Right<br />

Thing to Do?<br />

Taxes are right there in the same passage. God not only claims service <strong>from</strong> firstborn<br />

children, God taxes the Israelites their firstborn cattle. Later, we'll see that the Israelites'<br />

crops are taxed as well: first fruits and grains for God, gleanings and leavings of the<br />

field for God's poor. Let's not forget the commandment for a Jewish ID system. No, I'm<br />

not talking about circumcision (even though it's mentioned in this week's portion at<br />

Exodus 12:43–48), primarily because that particular Jewish marking is usually not<br />

visible. But the portion commands that we Jews mark our doorposts (mezuzah) at<br />

Exodus 12:24; and wear tefillin (in the final verse of this week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading).<br />

I freely admit that all of these rituals don't sound like domestic policy regulation to us,<br />

but they certainly did to the fledgling nation of Israel. With our American ethos of the<br />

separation of church and state (which is a very good thing); we often fail to see how our<br />

ancestors imagined politics and religion to be two complementary manifestations of<br />

national identity-as do most other nations of the world today. Which brings me back to<br />

war, foreign policy, and what the <strong>Torah</strong> may teach us.<br />

Diplomacy (speaking softly) carries little sway without a willingness to wield the big<br />

stick. Moses has no success with Pharaoh through moral suasion. Pharaoh is disdainful<br />

of God, and of Moses and the Israelites, until the plagues start raining down upon him.<br />

Only God's big stick gives Moses the ability to bargain with Pharaoh. As in the case of<br />

Pharaoh and others after him—we cannot read this story without hearing the words of<br />

the Passover Haggadah, "in every generation they rose up against us to destroy us"—<br />

there were times in Jewish history when military might was called for to ensure the<br />

survival of the Jewish people.<br />

But the <strong>Torah</strong> also teaches us that diplomacy must also be part of our national<br />

narrative. In Deuteronomy 20:10–12, God commands that we always first offer terms of<br />

peace. Only if peace is rejected by an overt act of war may we take up arms against our<br />

enemies. This commandment gave rise to "just war" theory, which has been pursued by<br />

governments <strong>from</strong> the time of Maimonides to our current American administration.<br />

Soon we will gather around our televisions for that rite we call the State of the Union. It<br />

is our obligation as Americans to listen with care to what our president reports, whether<br />

we agree or disagree. This week's <strong>Torah</strong> reading teaches us also to listen as Jews.<br />

The publication and distribution of the <strong>JTS</strong> Commentary are made possible by a generous grant<br />

<strong>from</strong> Rita Dee and Harold (z”l) Hassenfeld.<br />

Taste of <strong>Torah</strong><br />

A Comment on Ramban by Rabbi Matthew Berkowitz<br />

Exodus 12:1–2 The Lord said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt: this<br />

month will mark for you the beginning of the months; it will be the first of the<br />

months of the year for you.<br />

Ramban, “this month will mark for you the beginning of the months,” This<br />

order of the counting of the months is not in regard to the years, for the beginning<br />

of our years is <strong>from</strong> Tishrei, the seventh month . . . If so, when we call the month<br />

of Nisan the first of the months and Tishrei the seventh, the meaning is “the first<br />

month of the redemption” and “the seventh month <strong>from</strong> the redemption.” This is<br />

the meaning of the expression “it will be the first of the months of the year for<br />

you,” meaning that it is not the first in regard to the year but it is the first “for you”;<br />

in other words, it is called “the first” for the purpose of remembering our<br />

redemption.<br />

The first of Tishrei, commonly known as Rosh Hashanah, is celebrated in the<br />

Jewish community as the “official” New Year. Parashat <strong>Bo</strong>, however, undermines<br />

this traditional understanding. At the beginning of Exodus 12, God speaks to<br />

Moses and Aaron and declares that the month of Nisan, in which Passover<br />

occurs, “will mark for you the beginning of the months.” And if that weren’t enough<br />

to confuse us, the Mishnah teaches, not only are there two New Years, but there<br />

are actually four. Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 1:1 explains that the first of Nisan is<br />

the New Year for kings and festivals; the first of Elul is the New Year for tithing of<br />

animals; the first of Tishrei is the New Year for years; and the fifteenth of Shevat<br />

(coming up) is the New Year for trees. How do we reconcile the <strong>Torah</strong>’s teaching<br />

of Nisan as the beginning of the biblical year with the common understanding of<br />

Rosh Hashanah, Tishrei, as the start of the annual cycle?<br />

Ramban contends that in order to understand the biblical commandment, which is<br />

the first given to the Israelite nation, emphasis must be placed on lakhem (for<br />

you). Ramban, sensitively, explains that Nisan represents the first month in<br />

celebration of the Israelite redemption <strong>from</strong> Egypt. It is a month that marks the<br />

beginning of the year for the Jewish people as it marks the pivotal event of yetziat<br />

Mitzrayim. And so, it is the beginning of the counting of the years for you. In other<br />

words, <strong>Torah</strong> recognizes Nisan as the particular new year of the Jewish people<br />

throughout the generations. Nisan is bound intimately with the Israelite transition<br />

<strong>from</strong> slavery to redemption. If Nisan is so central to Jewish identity, why then do<br />

we need Rosh Hashanah?<br />

Nisan and Tishrei represent the poles of the particular and the universal. As<br />

Ramban explains, Nisan is “for you”: it is for the Jewish people in recognition of<br />

their freedom. Tishrei, or Rosh Hashanah, celebrates the birth of the world and<br />

God’s Kingship—clearly more universal in scope. It is between these two poles<br />

that the modern Jew maneuvers—taking to heart the experience of redemption<br />

while seeing oneself as part and parcel of humanity.<br />

With wishes for a good week and Shabbat Shalom.<br />

The publication and distribution of A Taste of <strong>Torah</strong> are made possible by a generous grant <strong>from</strong><br />

Sam and Marilee Susi.