Hate Crime and Vilification Law: Developments - The University of ...

Hate Crime and Vilification Law: Developments - The University of ...

Hate Crime and Vilification Law: Developments - The University of ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

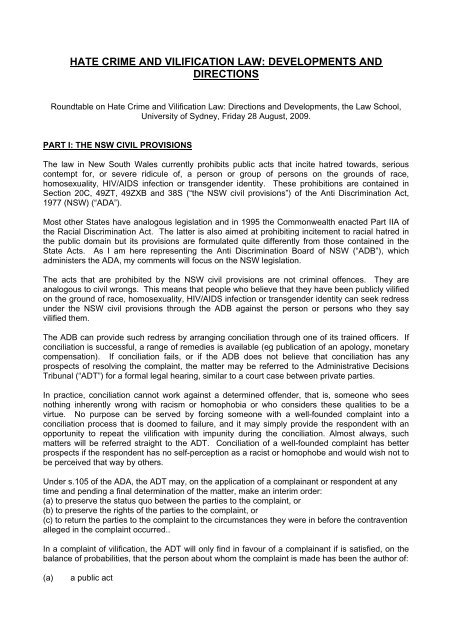

HATE CRIME AND VILIFICATION LAW: DEVELOPMENTS AND<br />

DIRECTIONS<br />

Roundtable on <strong>Hate</strong> <strong>Crime</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Vilification</strong> <strong>Law</strong>: Directions <strong>and</strong> <strong>Developments</strong>, the <strong>Law</strong> School,<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sydney, Friday 28 August, 2009.<br />

PART I: THE NSW CIVIL PROVISIONS<br />

<strong>The</strong> law in New South Wales currently prohibits public acts that incite hatred towards, serious<br />

contempt for, or severe ridicule <strong>of</strong>, a person or group <strong>of</strong> persons on the grounds <strong>of</strong> race,<br />

homosexuality, HIV/AIDS infection or transgender identity. <strong>The</strong>se prohibitions are contained in<br />

Section 20C, 49ZT, 49ZXB <strong>and</strong> 38S (“the NSW civil provisions”) <strong>of</strong> the Anti Discrimination Act,<br />

1977 (NSW) (“ADA”).<br />

Most other States have analogous legislation <strong>and</strong> in 1995 the Commonwealth enacted Part IIA <strong>of</strong><br />

the Racial Discrimination Act. <strong>The</strong> latter is also aimed at prohibiting incitement to racial hatred in<br />

the public domain but its provisions are formulated quite differently from those contained in the<br />

State Acts. As I am here representing the Anti Discrimination Board <strong>of</strong> NSW (“ADB”), which<br />

administers the ADA, my comments will focus on the NSW legislation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> acts that are prohibited by the NSW civil provisions are not criminal <strong>of</strong>fences. <strong>The</strong>y are<br />

analogous to civil wrongs. This means that people who believe that they have been publicly vilified<br />

on the ground <strong>of</strong> race, homosexuality, HIV/AIDS infection or transgender identity can seek redress<br />

under the NSW civil provisions through the ADB against the person or persons who they say<br />

vilified them.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ADB can provide such redress by arranging conciliation through one <strong>of</strong> its trained <strong>of</strong>ficers. If<br />

conciliation is successful, a range <strong>of</strong> remedies is available (eg publication <strong>of</strong> an apology, monetary<br />

compensation). If conciliation fails, or if the ADB does not believe that conciliation has any<br />

prospects <strong>of</strong> resolving the complaint, the matter may be referred to the Administrative Decisions<br />

Tribunal (“ADT”) for a formal legal hearing, similar to a court case between private parties.<br />

In practice, conciliation cannot work against a determined <strong>of</strong>fender, that is, someone who sees<br />

nothing inherently wrong with racism or homophobia or who considers these qualities to be a<br />

virtue. No purpose can be served by forcing someone with a well-founded complaint into a<br />

conciliation process that is doomed to failure, <strong>and</strong> it may simply provide the respondent with an<br />

opportunity to repeat the vilification with impunity during the conciliation. Almost always, such<br />

matters will be referred straight to the ADT. Conciliation <strong>of</strong> a well-founded complaint has better<br />

prospects if the respondent has no self-perception as a racist or homophobe <strong>and</strong> would wish not to<br />

be perceived that way by others.<br />

Under s.105 <strong>of</strong> the ADA, the ADT may, on the application <strong>of</strong> a complainant or respondent at any<br />

time <strong>and</strong> pending a final determination <strong>of</strong> the matter, make an interim order:<br />

(a) to preserve the status quo between the parties to the complaint, or<br />

(b) to preserve the rights <strong>of</strong> the parties to the complaint, or<br />

(c) to return the parties to the complaint to the circumstances they were in before the contravention<br />

alleged in the complaint occurred..<br />

In a complaint <strong>of</strong> vilification, the ADT will only find in favour <strong>of</strong> a complainant if is satisfied, on the<br />

balance <strong>of</strong> probabilities, that the person about whom the complaint is made has been the author <strong>of</strong>:<br />

(a) a public act

(b) which incites<br />

(c) hatred towards, serious contempt for, or severe ridicule <strong>of</strong> a person or group <strong>of</strong> persons<br />

2<br />

(d) on the ground <strong>of</strong> the race or homosexuality or HIV/AIDS infection or transgender identity <strong>of</strong><br />

the person or group (“the prohibited grounds”).<br />

It is a complete defence to a complaint made under the civil provisions that the act complained <strong>of</strong><br />

falls within subsection (2) <strong>of</strong> the relevant section, that is that the act was either a fair report <strong>of</strong> a<br />

public act, or a communication in respect <strong>of</strong> which a defence <strong>of</strong> absolute privilege would apply in<br />

defamation proceedings or a public act, done reasonably <strong>and</strong> in good faith, for academic, artistic,<br />

scientific or research purposes or for other purposes in the public interest, including discussion or<br />

debate about <strong>and</strong> expositions <strong>of</strong> any act or matter. If the four elements required to establish a<br />

complaint are proved, the onus shifts to the respondent to establish one or more <strong>of</strong> the defences.<br />

This is no simple task, particularly if the respondent must also prove that he or she acted<br />

“reasonably <strong>and</strong> in good faith”, as is usually the case.<br />

I am attaching some statistics produced by the ADB breaking down vilification complaints it<br />

received in the financial years 2006-2007, 2007-2008, 2008-2009. <strong>The</strong> statistics are <strong>of</strong> some, but<br />

limited, utility. <strong>The</strong> ADB received more than 1100 complaints under the ADA in each <strong>of</strong> the last<br />

three financial years, but only 2% or 3% in each year were complaints <strong>of</strong> vilification. <strong>The</strong> relatively<br />

small number <strong>of</strong> complaints <strong>of</strong> vilification might be due to the fact that many, if not most, complaints<br />

<strong>of</strong> racial vilification are directed to the Australian Human Rights Commission under the Federal<br />

legislation, which does not address other forms <strong>of</strong> vilification. According to information on the<br />

Commission’s website, “[d]uring 2005-06, the Commission received 259 complaints under the<br />

Racial Discrimination Act (this includes complaints lodged under the racial hatred provisions).<br />

Employment, the provision <strong>of</strong> services <strong>and</strong> racial hatred were the main areas <strong>of</strong> complaint”. (See<br />

http://www.hreoc.gov.au/about/media/speeches/race/2007/addressing_racism_in_australia.html<br />

accessed on 17 August 2009).<br />

<strong>The</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> vilification complaints to the ADB over the last three financial years were <strong>of</strong> racial<br />

vilification. Homosexual vilification came second. <strong>The</strong> number <strong>of</strong> complaints <strong>of</strong> transgender <strong>and</strong><br />

HIV vilification was very small. Of course not every incident <strong>of</strong> vilification is the subject <strong>of</strong> a<br />

complaint to the ADB or the Commission <strong>and</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> complaints is therefore not a reliable<br />

guide to the incidence <strong>of</strong> vilification in New South Wales or elsewhere. But one can safely<br />

conclude that complaints to the ADA, unlike those made to the Commission, are only infrequently<br />

about vilification.<br />

Yet complaints <strong>of</strong> vilification are usually among the most contentious <strong>of</strong> the complaints received by<br />

the ADB. In two <strong>of</strong> the three years under review, none <strong>of</strong> those complaints was resolved through<br />

conciliation. In the other year, only 3 out <strong>of</strong> 27, or 11%, were successfully conciliated. Most<br />

vilification complaints ended up being declined, withdrawn or ab<strong>and</strong>oned. This might perhaps<br />

indicate that they lacked merit or, alternatively, that they were well-founded but the complainants<br />

were unwilling to put themselves through the legal process. <strong>The</strong> next largest group <strong>of</strong><br />

complainants, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, were those who fought out their complaints in the ADT.<br />

Regrettably I was not able to get statistics about the success <strong>and</strong> failure rates <strong>of</strong> complaints <strong>of</strong><br />

vilification that are litigated in the ADT; the remedies sought; or the reasons for the failure <strong>of</strong><br />

litigated complaints that are unsuccessful. <strong>The</strong> high rate <strong>of</strong> discontinuance <strong>of</strong> vilification complaints<br />

<strong>and</strong> the fact that most complaints <strong>of</strong> racial vilification in New South Wales appear to be made<br />

under Federal legislation raise a question about the efficacy <strong>of</strong> the legislative scheme in New<br />

South Wales. Is it simply too difficult to pursue even a well-founded complaint <strong>of</strong> vilification to a<br />

successful conclusion under the ADA?<br />

A review <strong>of</strong> the NSW civil provisions might provide some answers. I will begin by considering each<br />

element in turn.

(a) Public act<br />

3<br />

<strong>The</strong> expression “public act” is defined in Sections 20B, 38R, 29ZS <strong>and</strong> 49ZXA <strong>of</strong> the ADA. <strong>The</strong><br />

expression extends to “any form <strong>of</strong> communication to the public”, “any conduct...observable by the<br />

public” <strong>and</strong> “the distribution or dissemination <strong>of</strong> any matter to the public with knowledge that the<br />

matter promotes or expresses hatred towards, serious contempt for, or severe ridicule <strong>of</strong>, a person<br />

or group <strong>of</strong> persons” on one <strong>of</strong> the prohibited grounds.<br />

<strong>The</strong> word “public” is not defined in the legislation. <strong>The</strong> jurisprudence in this <strong>and</strong> other areas <strong>of</strong> the<br />

law <strong>and</strong> other jurisdictions suggests that courts are inclined to give a broad interpretation to the<br />

word “public” <strong>and</strong> to exclude from its scope only those circumstances that might be characterized<br />

as purely domestic, for example, a conversation in a private home that cannot be overheard.<br />

This leads to the fundamental question <strong>of</strong> whether a public element should be included at all as<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the elements <strong>of</strong> serious vilification. On one view, the harms <strong>of</strong> vilification are at least as real<br />

in circumstances where the vilifier <strong>and</strong> the victim are alone together as they are where the victim is<br />

not present <strong>and</strong> the vilification is directed to a large audience. <strong>The</strong> contrary view is that the<br />

legislation is directed at addressing a social rather than a personal harm <strong>and</strong> the social harm<br />

arises only when the vilification occurs in a public context.<br />

Another question arises out <strong>of</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> communications technology. Section 20B was<br />

enacted in 1989. <strong>The</strong> other three sections, all enacted subsequently, essentially replicate section<br />

20B. In 1989, the internet had not developed into the widely used, publicly accessible medium that<br />

it has since become. A very large volume <strong>of</strong> material is now published on the internet <strong>and</strong> may be<br />

accessed generally by any member <strong>of</strong> the public, usually without the necessity for any payment.<br />

Under Part IIA <strong>of</strong> the RDA, a vilificatory act is unlawful only if it is done “otherwise than in private”.<br />

<strong>The</strong> case law has established that placing material on the internet that is freely available <strong>and</strong> not<br />

password protected is an act done “otherwise than in private”: Jones v. Toben [2002] FCA 1150<br />

(17 September 2002) (para.75) <strong>and</strong> Toben v. Jones [2003] FCAF 137 (27 June 2003). As was<br />

determined by the High Court <strong>of</strong> Australia in Dow Jones v Gutnick (2002) 210 CLR 575; [2002]<br />

HCA 56, in relation to the net, publication is not a single event located by reference only to the<br />

publisher's conduct. It occurs each time a reader downloads the material.<br />

Amending the definitions <strong>of</strong> “public act” in the ADA so as to incorporate this jurisprudence would<br />

bring the anti-vilification provisions <strong>of</strong> the ADA into the internet age <strong>and</strong> in line with the judicial<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> the equivalent provisions <strong>of</strong> Part IIA <strong>of</strong> the RDA.<br />

(b) Incites<br />

<strong>The</strong> word “incite” is not defined in either the civil provisions or the criminal provisions <strong>of</strong> the ADA.<br />

Cases that have arisen out <strong>of</strong> the civil provisions (<strong>and</strong> analogous provisions in other jurisdictions<br />

outside NSW) have defined the expression to mean “to urge on, stimulate or prompt to action”.<br />

This is based on the Macquarie Dictionary definition <strong>of</strong> the word “incite”.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Oxford Dictionary definition includes “stir up, animate”. It therefore seems reasonably clear<br />

that the concept <strong>of</strong> incitement involves stimulating others to do something or to feel something.<br />

This allows for the possibility that incitement may occur when the feelings <strong>of</strong> others are aroused,<br />

even if they do not act on those feelings. Both the civil provisions <strong>and</strong> the criminal provisions <strong>of</strong><br />

the ADA focus on the stirring up <strong>of</strong> feelings (i.e. “hatred”, “serious contempt”, “severe ridicule”)<br />

<strong>and</strong>, in the case <strong>of</strong> the criminal provisions, on the means used to do so, rather than on any<br />

consequential action that may be taken or threatened, or the effect on the victims.

4<br />

<strong>The</strong> legislation does not make it clear whether pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> incitement requires evidence that others<br />

have in fact been incited. In certain cases that have come before the Courts, those accused <strong>of</strong><br />

incitement have sought to argue that the concept <strong>of</strong> incitement encompasses both the act <strong>of</strong> the<br />

alleged inciter <strong>and</strong> the reaction <strong>of</strong> those who have been incited. <strong>The</strong>y have contended that pro<strong>of</strong> is<br />

required that other people have actually been incited.<br />

However, the Courts have not accepted that contention. <strong>The</strong> case law establishes that<br />

“incitement” can be proved even in the absence <strong>of</strong> evidence that other people have in fact been<br />

roused to hatred (or to acting upon that hatred). Rather, the test is whether a hypothetical<br />

audience <strong>of</strong> reasonable people who are neither immune from, nor particularly susceptible to,<br />

feelings <strong>of</strong> hatred on one <strong>of</strong> the prohibited grounds would be incited.<br />

An alternative approach would be to ab<strong>and</strong>on the terminology <strong>of</strong> incitement altogether in favour <strong>of</strong><br />

some other test. I discuss this in more detail in the section headed “<strong>The</strong> Criminal Provisions”.<br />

(c) Hatred, serious contempt or severe ridicule<br />

Anti-vilification legislation in other States in Australia has replicated the formulation “hatred<br />

towards, serious contempt for, or severe ridicule <strong>of</strong>” that appears in the ADA. Federally, Part IIA <strong>of</strong><br />

the Racial Discrimination Act employs the expression “hatred” only. Examples <strong>of</strong> both formulations<br />

can be found in analogous legislative provisions in other countries. Little seems to turn on the<br />

distinction, even though “serious contempt” <strong>and</strong> “severe ridicule” are arguably less stringent criteria<br />

than “hatred”.<br />

<strong>The</strong> interpretation <strong>of</strong> these words does not seem to have presented courts in Australia or overseas<br />

with undue difficulty. <strong>The</strong> plain dictionary definition <strong>of</strong> these words entails something in the nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> intense or active dislike. That definition excludes much material that would widely be regarded<br />

as innocuous. For example, humour based on ethnic or homosexual stereotypes, considered in<br />

context, can <strong>of</strong>ten be accepted as light-hearted <strong>and</strong> even, in a uniquely Australian way,<br />

affectionate. It would clearly fall outside the operation <strong>of</strong> the criminal (<strong>and</strong> civil) provisions.<br />

Western Australia’s legislation has exp<strong>and</strong>ed the scope <strong>of</strong> the behaviour that is prohibited to<br />

include behaviour whose effect is “to threaten [or] seriously <strong>and</strong> substantially abuse” others on a<br />

prohibited ground. But these formulations are used in the context <strong>of</strong> a Criminal Code proscribing<br />

criminal conduct <strong>and</strong> do not sit comfortably with legislative provisions which impose civil<br />

prohibitions.<br />

(d) <strong>The</strong> Prohibited Grounds<br />

Neither the civil provisions nor the criminal provisions <strong>of</strong> the ADA apply unless there has been a<br />

public act <strong>of</strong> incitement to hatred <strong>of</strong> a person or group on one <strong>of</strong> four grounds, namely:<br />

(i) Race<br />

(ii) Homosexuality<br />

(iii) HIV/Aids infection; or<br />

(iv) Transgender identity (ie being a transgender person).<br />

“Race” is defined in s.4 <strong>of</strong> the ADA as including “colour, nationality, descent <strong>and</strong> ethnic, ethnoreligious<br />

or national origin”. This broad definition is declaratory <strong>of</strong> the case law on the meaning <strong>of</strong><br />

“race” as it has developed both in Australia <strong>and</strong> overseas. However, vilification solely on the<br />

ground <strong>of</strong> religion would fall outside the prohibitions contained in the ADA.<br />

<strong>The</strong> existing prohibited grounds therefore afford protection against vilification only to some groups.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se groups appear to have been selected on the basis <strong>of</strong> a well-recorded history <strong>of</strong> their<br />

members being victims <strong>of</strong> hatred. A question arises whether the prohibited grounds should be

5<br />

enlarged to extend that protection to other groups. <strong>The</strong> NSW <strong>Law</strong> Reform Commission’s (LRC)<br />

Report No. 92 considered whether there should be three further prohibited grounds, namely<br />

gender, disabilities <strong>and</strong> religion, but the LRC did not recommend that any <strong>of</strong> them be included.<br />

<strong>The</strong> arguments for <strong>and</strong> against exp<strong>and</strong>ing the prohibited grounds are well summarized in LRC<br />

Report 92 <strong>and</strong> need not be repeated here.<br />

Some protection is already provided in the existing legislation to religious minorities by the<br />

inclusion <strong>of</strong> “ethno-religious origin” as a prohibited ground. However, the way the case law has<br />

developed, there is no prohibition in New South Wales against criticizing the beliefs or practices <strong>of</strong><br />

a particular religion on exclusively philosophical or theological grounds. <strong>The</strong> only restriction is that<br />

if the adherents <strong>of</strong> that religion are also an ethno-religious group, the manner <strong>of</strong> such criticism<br />

must not collectively vilify the group.<br />

<strong>The</strong> question <strong>of</strong> which categories <strong>of</strong> groups should be protected is not the only issue that arises.<br />

Section 88 <strong>of</strong> the ADA precludes a vilification complaint from being made by anyone who does not<br />

have, or reasonably claim to have, the characteristic that was the ground <strong>of</strong> the alleged vilification.<br />

This means that the protection afforded by the criminal (<strong>and</strong> civil) provisions extends only to<br />

persons who are actually members <strong>of</strong> the groups referred to in those provisions but not to persons<br />

who are vilified because they are presumed to be members.<br />

Clearly, a person may be publicly vilified, say, as a homosexual even though that person is not a<br />

homosexual. <strong>The</strong> question therefore arises whether the legislation should be amended so that the<br />

protection afforded by the criminal provisions extends to any person or group <strong>of</strong> people because <strong>of</strong><br />

their actual or presumed race, homosexuality, HIV/AIDS infection or transgender identity.<br />

In Western Australia, again in the context <strong>of</strong> proving criminal <strong>of</strong>fences, there is no requirement that<br />

victims be actual members <strong>of</strong> the relevant protected group. A conviction may be secured even if<br />

that is not the case, <strong>and</strong> the alleged <strong>of</strong>fender merely believed it to be so, correctly or incorrectly. I<br />

can see no reason in logic or principle why the protection afforded by both the civil <strong>and</strong> criminal<br />

provisions in NSW should not extend to any person or group <strong>of</strong> people because <strong>of</strong> their presumed<br />

(even if not actual) characteristics under one <strong>of</strong> the prohibited grounds.<br />

PART II: THE NSW CRIMINAL PROVISIONS<br />

Even though this paper principally addresses the NSW civil provisions, I would like to make some<br />

brief observations also about the corresponding criminal provisions contained in Sections 20D,<br />

49ZTA, 49ZXC or 38T <strong>of</strong> the ADA (“the criminal provisions”). A prosecution under any <strong>of</strong> the<br />

criminal provisions cannot succeed unless each <strong>of</strong> the four elements specified in the civil<br />

provisions are proved. And they must be proved to the criminal st<strong>and</strong>ard, that is, beyond<br />

reasonable doubt. A fifth element must also proved. <strong>The</strong> incitement must occur:<br />

“by means which include either:<br />

(i) threatening physical harm towards, or towards any property <strong>of</strong>, the person or group<br />

<strong>of</strong> persons, or<br />

(ii) inciting others to threaten physical harm towards, or towards any property <strong>of</strong>, the<br />

person or group <strong>of</strong> persons.”<br />

Under the ADA a person cannot be prosecuted under the criminal provisions unless the Attorney<br />

General <strong>of</strong> NSW has consented to the prosecution. In point <strong>of</strong> fact, not a single person in New<br />

South Wales has ever been prosecuted for, let alone convicted <strong>of</strong>, a criminal <strong>of</strong>fence under any <strong>of</strong><br />

the criminal provisions. Altogether, there were 16 occasions between 1993 <strong>and</strong> 2008 when the<br />

Attorney General referred to the Director <strong>of</strong> Public Prosecutions (DPP) complaints received by the<br />

President <strong>of</strong> the ADB to consider whether an <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>of</strong> serious vilification might have occurred.

6<br />

<strong>The</strong> fact that there have been no prosecutions raises the question <strong>of</strong> whether there is a gap<br />

between the way legislators <strong>and</strong> the public have expected the criminal provisions to operate <strong>and</strong><br />

the way they in fact operate – an “expectation gap”. If there is such a gap, the main reason<br />

according to the advice received from the DPP is the need to prove two <strong>of</strong> the elements <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>of</strong>fence that are particularly difficult to prove – the “incitement” element <strong>and</strong> the “means” element.<br />

(a) <strong>The</strong> ‘incitement’ element<br />

I have already mentioned the difficulties involved in proving ‘incitement’, even in the civil context<br />

<strong>and</strong> to the civil st<strong>and</strong>ard. Are there alternatives, particularly in the context <strong>of</strong> the NSW criminal<br />

provisions?<br />

Article 4 <strong>of</strong> the International Convention on the Elimination <strong>of</strong> All Forms <strong>of</strong> Racial Discrimination, to<br />

which Australia is a party, requires States to “declare as an <strong>of</strong>fence punishable by law all<br />

dissemination <strong>of</strong> ideas based on racial superiority or hatred” (see para. (a)).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Convention thus seems to require that the mere expression <strong>and</strong> advocacy <strong>of</strong> racial hatred to<br />

others ought to be made a punishable <strong>of</strong>fence. Implicit in this requirement is the proposition that<br />

the mere dissemination <strong>of</strong> ideas <strong>of</strong> racial hatred necessarily involves a sufficiently serious breach<br />

<strong>of</strong> the peace to justify the imposition <strong>of</strong> criminal sanctions. As noted earlier, there may well be<br />

sound sociological <strong>and</strong> historical reasons for accepting that proposition, although it remains<br />

controversial <strong>and</strong> would almost certainly be challenged by some on civil liberties grounds.<br />

Moreover, removing the terminology <strong>of</strong> incitement from the ADA <strong>and</strong> replacing it with new<br />

terminology, such as “the dissemination <strong>of</strong> hatred” on any <strong>of</strong> the prohibited grounds, would involve<br />

jettisoning the body <strong>of</strong> jurisprudence that has developed in Australia in particular around the<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> incitement. Whatever benefit may be obtained from removing the difficulties inherent in<br />

the concept <strong>of</strong> incitement from the criminal provisions may well be outweighed by introducing<br />

entirely new concepts whose interpretation by the Courts could not be predicted.<br />

Neither the civil nor the criminal provisions <strong>of</strong> the ADA expressly require that the incitement be<br />

intentional. When anti-vilification laws were first introduced in New South Wales in 1989, the then<br />

Attorney-General said in his Second Reading Speech that intention to incite would need to be<br />

proved in order to establish a breach <strong>of</strong> the criminal provisions, but not <strong>of</strong> the civil provisions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> argument that pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> intention to incite ought to be a requirement for securing a conviction<br />

under the criminal provisions derives from the common law concept that the element <strong>of</strong> mens rea<br />

(literally “guilty mind”) must be present to justify the imposition <strong>of</strong> criminal sanctions. Satisfying<br />

this requirement in any criminal prosecution usually entails pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> criminal intent or at least<br />

reckless indifference by the accused to the consequences <strong>of</strong> the proscribed behaviour.<br />

<strong>The</strong> counter-argument is that public acts <strong>of</strong> vilification on any <strong>of</strong> the prohibited grounds ought to be<br />

criminalised whether or not there is intent or recklessness, because <strong>of</strong> the destructive message<br />

that would be conveyed to society if those acts went unpunished.<br />

One possible way <strong>of</strong> dealing with the mens rea element would be to introduce two types <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fence<br />

to proscribe vilificatory behaviour. <strong>The</strong> first <strong>of</strong>fence would require pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> an intention to incite<br />

hatred <strong>and</strong> would carry the heavier penalty. <strong>The</strong> second <strong>of</strong>fence would be in the nature <strong>of</strong> a strict<br />

liability <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>and</strong> would require pro<strong>of</strong> only <strong>of</strong> the likelihood (or reasonable likelihood) <strong>of</strong> a<br />

proscribed outcome. A person charged with the first <strong>of</strong>fence could, if intention is not proved, be<br />

liable nevertheless to be convicted <strong>of</strong> the second <strong>of</strong>fence, if the evidence is sufficient to prove the<br />

elements <strong>of</strong> the second <strong>of</strong>fence.

7<br />

In essence, this is the regime that was introduced in <strong>The</strong> Criminal Code <strong>of</strong> Western Australia in<br />

2004. <strong>The</strong> “strict liability <strong>of</strong>fences” in that Code are framed in identical terms to the criminal<br />

<strong>of</strong>fences but without the element <strong>of</strong> intent. If the proscribed conduct is merely “likely” to incite<br />

racial animosity or racist harassment or to result in racist harassment, the <strong>of</strong>fence in each case will<br />

be proved. <strong>The</strong> word “likely” is usually associated with the civil st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong>, <strong>and</strong> its<br />

appearance in a criminal statute might be considered anomalous.<br />

Further, there are defences that are available to a person accused <strong>of</strong> committing any <strong>of</strong> the strict<br />

liability <strong>of</strong>fences, which are not available to persons accused <strong>of</strong> the intentional <strong>of</strong>fences. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

defences are set out in Section 80G. In essence, these defences excuse conduct that is done<br />

“reasonably <strong>and</strong> in good faith” if the conduct was either a fair report <strong>of</strong> a public act, or a<br />

communication in respect <strong>of</strong> which a defence <strong>of</strong> absolute privilege would apply in defamation<br />

proceedings or a public act, done reasonably <strong>and</strong> in good faith, for academic, artistic, scientific or<br />

research purposes or for other purposes in the public interest, including discussion or debate about<br />

<strong>and</strong> expositions <strong>of</strong> any act or matter. <strong>The</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> these defences can provide an accused<br />

person with the opportunity <strong>of</strong> using the proceedings to gr<strong>and</strong>-st<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> repeat the vilificatory<br />

conduct in the court-room with impunity.<br />

(b) <strong>The</strong> ‘means’ element<br />

Even the most egregious examples <strong>of</strong> public acts <strong>of</strong> incitement to hatred on one <strong>of</strong> the prohibited<br />

grounds will not attract criminal sanctions unless it can be proved, beyond reasonable doubt, that<br />

the means <strong>of</strong> incitement were those stipulated in the criminal provisions. This element, the<br />

“means” element, presents perhaps an even more significant evidentiary hurdle than the need to<br />

prove incitement <strong>and</strong>, perhaps more than any other factor, accounts for the fact that there have<br />

been no prosecutions for serious vilification in New South Wales to date.<br />

<strong>The</strong> policy underpinning the inclusion <strong>of</strong> this element in the criminal provisions is that public<br />

incitement to hatred on a prohibited ground is said not to be sufficiently serious to warrant the<br />

imposition <strong>of</strong> criminal sanctions, even if the incitement is proved beyond reasonable doubt to have<br />

been intentional. Only a contemporaneous threat <strong>of</strong> harm to a person or property is said to justify<br />

criminalising vilificatory behaviour.<br />

And yet it seems clear that a vilificatory act need not be accompanied by, or itself constitute, a<br />

threat, or incitement to others to threaten, physical harm to person or property, <strong>and</strong> the act may<br />

nonetheless be perceived by the target person or group (<strong>and</strong> by others) – <strong>and</strong> reasonably<br />

perceived – as extremely threatening. <strong>The</strong> threat may be unmistakable to a reasonable observer<br />

even if it is merely implicit <strong>and</strong> not provable beyond reasonable doubt.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a strong argument to be made that public incitement <strong>of</strong> hatred on any <strong>of</strong> the prohibited<br />

grounds, <strong>of</strong> itself, entails a breach <strong>of</strong> the peace, <strong>and</strong> that criminal sanctions are therefore<br />

appropriate where the incitement is intentional. Even if the incitement is not immediately<br />

accompanied by a threat <strong>of</strong> physical harm, or by an incitement <strong>of</strong> others to threaten physical harm,<br />

the incitement <strong>of</strong> the public to hatred on one <strong>of</strong> the prohibited grounds contributes to the creation <strong>of</strong><br />

a social climate that is more conducive to the occurrence <strong>of</strong> acts or threats <strong>of</strong> physical harm to the<br />

groups that are targeted, <strong>and</strong> more conducive to social violence in general.<br />

Also, threats <strong>of</strong> physical harm towards a person or property, even in the absence <strong>of</strong> incitement to<br />

hatred, may well fall within the reach <strong>of</strong> the general provisions <strong>of</strong> the criminal law. For example, a<br />

person who “counsels or procures another” to commit a serious indictable <strong>of</strong>fence can be<br />

prosecuted as an accessory before the fact under section 346 <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Crime</strong>s Act (NSW) 1900. To<br />

“counsel” others would include urging or inciting them. Apprehended violence orders are available<br />

under Part 15A <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Crime</strong>s Act <strong>and</strong> a common assault, if sufficiently serious, can be prosecuted<br />

as an indictable <strong>of</strong>fence under Section 61 <strong>of</strong> that Act. <strong>The</strong> common law concept <strong>of</strong> assault

8<br />

encompasses acts that intentionally or recklessly put a victim in fear <strong>of</strong> physical or other unlawful<br />

danger.<br />

It follows that if there were to be a threat <strong>of</strong> physical harm towards a person or property, it would<br />

make sense to deal with it, where applicable, under the general criminal law so that there would be<br />

no need to prove the occurrence <strong>of</strong> (i) a public act (ii) that has incited hatred (iii) on one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

prohibited grounds. It would make no sense at all to prosecute the matter under the criminal<br />

provisions <strong>of</strong> the ADA, which impose penalties that are no higher than under other available<br />

provisions <strong>of</strong> the criminal law, but carry a far heavier evidentiary burden.<br />

In fact, conduct proscribed by s.20D <strong>of</strong> the ADA might be more heavily punished if prosecuted<br />

under other available provisions <strong>of</strong> the criminal law. A conviction under the <strong>Crime</strong>s Act 1900<br />

(NSW) for example can result in the imposition <strong>of</strong> enhanced penalties under Section 21 A(h) <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Crime</strong>s (Sentencing Procedure) Act, 1999 (NSW), which provides that one factor that can be taken<br />

into account in sentencing is whether: “the <strong>of</strong>fence was motivated by hatred for or prejudice against<br />

a group <strong>of</strong> people to which the <strong>of</strong>fender believed the victim belonged (such as people <strong>of</strong> a<br />

particular religion, racial or ethnic origin, language, sexual orientation or age, or having a particular<br />

disability”.<br />

However, the extent <strong>of</strong> the “enhancement” <strong>of</strong> the penalty is left entirely to the discretion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

sentencing judge. In most States <strong>of</strong> the USA, in contrast, the extent <strong>of</strong> penalty enhancement is<br />

prescribed by statute. Some 43 States (out <strong>of</strong> 50) <strong>and</strong> the District <strong>of</strong> Columbia have enacted such<br />

laws. An increase <strong>of</strong> 1/3 rd in the maximum term <strong>of</strong> imprisonment that would otherwise be<br />

applicable is typical <strong>of</strong> the way penalty enhancement provisions currently work in the US. In<br />

Wisconsin v Mitchell 508 U.S. 476 (1993), the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality <strong>of</strong> a<br />

penalty enhancement Statute directed against crimes motivated by hate based on the victim’s<br />

race, religion, national origin, sexual origin or gender.<br />

(c) Conclusions concerning the criminal provisions<br />

<strong>The</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong> serious vilification as a criminal <strong>of</strong>fence varies widely between Australia <strong>and</strong> other<br />

common law jurisdictions such as the UK, Canada <strong>and</strong> the US. Even among the States <strong>of</strong><br />

Australia, <strong>and</strong> the ACT, there are significant differences despite the many commonalities. In my<br />

view, short <strong>of</strong> a wholesale re-writing <strong>of</strong> the criminal provisions, reformers <strong>of</strong> anti-vilification law in<br />

New South Wales should focus primarily either on replacing the means element with something<br />

that will not operate in practice to emasculate the criminal provisions, as is presently the case, or<br />

better still, on simply eliminating the means element altogether.<br />

Peter Wertheim AM<br />

Statutory Board Member<br />

NSW Anti-Discrimination Board<br />

28 August 2009

9<br />

Breakdown Of <strong>Vilification</strong> Complaints Received In Financial Years 2006-<br />

2007, 2007-2008, 2008-2009<br />

Results for Financial Year 2006-2007<br />

2006-2007 Received<br />

Outcome Number % Conciliated<br />

Total <strong>Vilification</strong> Rec’d 35 0%<br />

HIV/Aids Vil. 0 0%<br />

Homosexual Vil. 11 0%<br />

Race Vil. 24 0%<br />

Transgender Vil. 0 0%<br />

Total complaints in Fin Year 2006-2007 = 1101<br />

% Of <strong>Vilification</strong> Complaints = 3%<br />

Results For Financial Year 2007-2008<br />

2007-2008 Received<br />

Outcome Number % Conciliated<br />

Total <strong>Vilification</strong> Rec’d 27 11%<br />

HIV/Aids Vil. 1 0%<br />

Homosexual Vil. 7 14%<br />

Race Vil. 16 6%<br />

Transgender Vil. 3 33%<br />

Total Complaints in Fin Year 2007-2008 = 1143<br />

% Of <strong>Vilification</strong> Complaints = 2%<br />

Type <strong>of</strong> <strong>Vilification</strong> <strong>and</strong> Outcomes<br />

Outcomes From Complaints Received in<br />

2006-2007<br />

Outcome Number<br />

Declined 12<br />

Withdrawn 6<br />

Referred To ADT 11<br />

Declined, Referred to ADT 2<br />

Conciliated 0<br />

Settled, no conference 0<br />

Ab<strong>and</strong>oned 3<br />

Referred to AG, Serious Vil. 1<br />

Outcomes From Complaints Received in<br />

2007-2008<br />

Outcome Number<br />

Declined 9<br />

Withdrawn 4<br />

Referred To ADT 5<br />

Declined, Referred to ADT 1<br />

Conciliated 3<br />

Settled, no conference 0<br />

Ab<strong>and</strong>oned 4<br />

Referred to AG, Serious Vil. 1

Results For Financial Year 2008-2009<br />

2008-2009 Received<br />

Outcome Number % Conciliated<br />

Total <strong>Vilification</strong> Rec’d 23 0%<br />

HIV/Aids Vil. 0 0%<br />

Homosexual Vil. 8 0%<br />

Race Vil. 13 0%<br />

Transgender Vil. 2 0%<br />

Total Complaints in Fin Year 2008-2009 = 1188<br />

% Of <strong>Vilification</strong> Complaints = 2%<br />

10<br />

Outcomes From Complaints Received<br />

in 2008-2009<br />

Outcome Number<br />

Declined 4<br />

Withdrawn 0<br />

Referred To ADT 3<br />

Declined, Referred to ADT 7<br />

Conciliated 0<br />

Settled, no conference 0<br />

Ab<strong>and</strong>oned 2<br />

Referred to AG, Serious Vil. 0<br />

Open 7