Biologically-Respectful Tourism - LinkBC

Biologically-Respectful Tourism - LinkBC

Biologically-Respectful Tourism - LinkBC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

For such a small community, exceptionally high levels of generosity and volunteerism were observed and documented in volunteer<br />

award celebration pamphlets as well as publications by Sunshine Coast Community Foundations. Some of the campaigns reached<br />

out to provincial and national partners. It was not uncommon to see lists of 15 – 25 major donor groups listed in the LOPM, WPM<br />

and education cluster campaigns stemming from community grants, provincial funding, and corporate environmental funds with<br />

a large influx of money from off‐coast sources.<br />

At least two fundraising galas were observed during the study. Both used the press to thank a list of more than 100 donors along<br />

with totals raised at the events in the order of tens of thousands of dollars.<br />

At least four of the projects were successful at securing $1,000,000 or more in capital through grants under Island Coastal Economic<br />

Trust (ICET) or Community Adjustment Fund (CAF), as well as numerous smaller local grants. Some of the campaigns within these<br />

three clusters were also able to use moneys received from bequests. One coast resident donated $100,000 to each of two coast<br />

projects posthumously. While there was much success reported in funding, a number of campaigns reported declines in their<br />

funding. While in the past government funding was common practice, such direct funding disappeared from several projects while<br />

government support continued to come in the form of technical expertise and advice. Access to capable grant writers and access to<br />

a network of donors are two effective means to generate funds.<br />

Organizations with high membership would be at an advantage as would those with experienced grant writers. Such realities may<br />

help explain the low membership pricing strategy commonly observed across most organizations with annual fees often in the range<br />

of $30 for an individual or $35 for a family. One organization with minimal membership fees reported 700 members with 125 noted<br />

to be ‘active.’ Without adequate fund‐raising or volunteer retention, often the project is compromised, the momentum is slowed<br />

and in at least one case only continued after funding from out‐of‐pocket expenditures were infused into the project.<br />

ENGAGING THE WIDER COMMUNITY IN THE PROCESS<br />

While the question regarding community stakeholder involvement was never posed, the issue was raised by many as a factor of<br />

their success. Stakeholder interests can easily pit community members against government or industry, and industry against<br />

organizations. By not engaging the community organizations risk polarization, diminished effectiveness, and inability to have local<br />

council adopt policies.<br />

Some highly effective campaigns approached this optimal stakeholder engagement. For instance the Francis Point Provincial Park<br />

and Ecological Reserve campaign (Bell & Adair, 2008, p. 1‐2) noted a high degree of public input, use of knowledgeable individuals,<br />

consultation with local First Nations, and engaging government officials at all levels. Engaging the community was a critical success<br />

factor in the Mt. Artaban Park creation by stimulating 91 industrial partners and individuals to make contributions exceeding the<br />

amount needed for the survey and management plan. During the Save our Sunshine Coast campaign, there was “almost 100%<br />

support from the communities”, the four governments, and the Sechelt Indian Band.<br />

A few of the campaigns exhibited narrow or singular viewpoints as evidenced at community forums or in exchanges reported in<br />

the press. While such observations are speculative, they do illustrate a publicly displayed level of divergence and resentment and<br />

suggest a need for wiser means of reaching agreement or consensus (Newsome, Dowling & Moore, 2005, p. 123; Priem, 1990, p.<br />

473; Senge, 1990, pp. 223‐231).<br />

USING SCIENTIFIC ASSESSMENT & SURVEYS<br />

As each of these projects centres on an ‘environmental’ theme, an assumption was made that the use of scientific studies would<br />

be beneficial in order to substantiate claims, or ensure the project was using the right protection mechanism. Q. 9 asked the<br />

respondents “how often did the organization use scientists or independent scientific studies to substantiate the campaign claims”?<br />

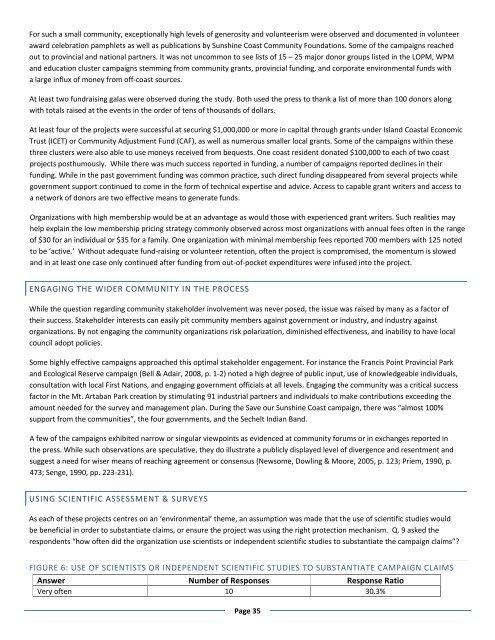

FIGURE 6: USE OF SCIENTISTS OR INDEPENDENT SCIENTIFIC STUDIES TO SUBSTANTIATE CAMPAIGN CLAIMS<br />

Answer Number of Responses Response Ratio<br />

Very often 10 30.3%<br />

Page 35