Eigse Paged 2004 - National University of Ireland

Eigse Paged 2004 - National University of Ireland

Eigse Paged 2004 - National University of Ireland

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

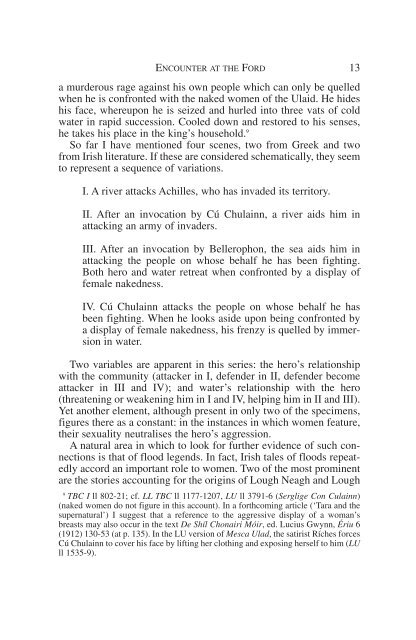

ENCOUNTER AT THE FORD 13<br />

a murderous rage against his own people which can only be quelled<br />

when he is confronted with the naked women <strong>of</strong> the Ulaid. He hides<br />

his face, whereupon he is seized and hurled into three vats <strong>of</strong> cold<br />

water in rapid succession. Cooled down and restored to his senses,<br />

he takes his place in the king’s household. 9<br />

So far I have mentioned four scenes, two from Greek and two<br />

from Irish literature. If these are considered schematically, they seem<br />

to represent a sequence <strong>of</strong> variations.<br />

I. A river attacks Achilles, who has invaded its territory.<br />

II. After an invocation by Cú Chulainn, a river aids him in<br />

attacking an army <strong>of</strong> invaders.<br />

III. After an invocation by Bellerophon, the sea aids him in<br />

attacking the people on whose behalf he has been fighting.<br />

Both hero and water retreat when confronted by a display <strong>of</strong><br />

female nakedness.<br />

IV. Cú Chulainn attacks the people on whose behalf he has<br />

been fighting. When he looks aside upon being confronted by<br />

a display <strong>of</strong> female nakedness, his frenzy is quelled by immersion<br />

in water.<br />

Two variables are apparent in this series: the hero’s relationship<br />

with the community (attacker in I, defender in II, defender become<br />

attacker in III and IV); and water’s relationship with the hero<br />

(threatening or weakening him in I and IV, helping him in II and III).<br />

Yet another element, although present in only two <strong>of</strong> the specimens,<br />

figures there as a constant: in the instances in which women feature,<br />

their sexuality neutralises the hero’s aggression.<br />

A natural area in which to look for further evidence <strong>of</strong> such connections<br />

is that <strong>of</strong> flood legends. In fact, Irish tales <strong>of</strong> floods repeatedly<br />

accord an important role to women. Two <strong>of</strong> the most prominent<br />

are the stories accounting for the origins <strong>of</strong> Lough Neagh and Lough<br />

9<br />

TBC I ll 802-21; cf. LL TBC ll 1177-1207, LU ll 3791-6 (Serglige Con Culainn)<br />

(naked women do not figure in this account). In a forthcoming article (‘Tara and the<br />

supernatural’) I suggest that a reference to the aggressive display <strong>of</strong> a woman’s<br />

breasts may also occur in the text De Shíl Chonairi Móir, ed. Lucius Gwynn, Ériu 6<br />

(1912) 130-53 (at p. 135). In the LU version <strong>of</strong> Mesca Ulad, the satirist Ríches forces<br />

Cú Chulainn to cover his face by lifting her clothing and exposing herself to him (LU<br />

ll 1535-9).