Challenging the Aquaculture Industry on Sustainability-Greenpeace ...

Challenging the Aquaculture Industry on Sustainability-Greenpeace ...

Challenging the Aquaculture Industry on Sustainability-Greenpeace ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

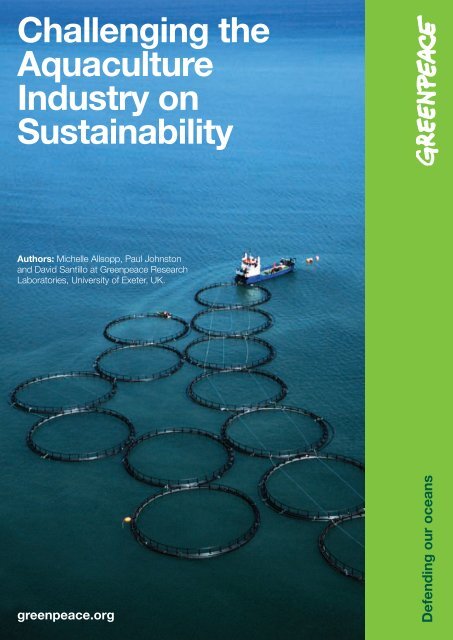

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Sustainability</strong><br />

Authors: Michelle Allsopp, Paul Johnst<strong>on</strong><br />

and David Santillo at <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Research<br />

Laboratories, University of Exeter, UK.<br />

greenpeace.org<br />

Defending our oceans

For more informati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tact:<br />

enquiries@int.greenpeace.org<br />

Authors: Michelle Allsopp,<br />

Paul Johnst<strong>on</strong> and David Santillo<br />

at <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Research Laboratories,<br />

University of Exeter, UK.<br />

Ackowledgements:<br />

With special thanks for advice and<br />

editing to Nina Thuellen, Evandro<br />

Oliveira, Sari Tolvanen, Bettina Saier,<br />

Giorgia M<strong>on</strong>ti, Cat Dorey, Karen Sack,<br />

Lindsay Keenan, Femke Nagel, Frida<br />

Bengtss<strong>on</strong>, Truls Gulowsen, Richard<br />

Page, Paloma Colmenarejo, Samuel<br />

Leiva, Sarah King and Mike Hagler.<br />

Printed <strong>on</strong> 100% recycled<br />

post-c<strong>on</strong>sumer waste with<br />

vegetable based inks.<br />

JN 106<br />

Published in January 2008<br />

by <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Ottho Heldringstraat 5<br />

1066 AZ Amsterdam<br />

The Ne<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rlands<br />

Tel: +31 20 7182000<br />

Fax: +31 20 5148151<br />

greenpeace.org<br />

Cover Image: <strong>Greenpeace</strong> / D Beltrá<br />

Design by neo: creative<br />

Printer: EL TINTER, S.A.L., Barcel<strong>on</strong>a – Spain<br />

©GREENPEACE / E DE MILDT

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong><br />

Part 1: Introducti<strong>on</strong> 4<br />

Part 2: Negative Impacts of<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> People and<br />

<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment 7<br />

Part 3: Use of Fishmeal/Fish Oil/<br />

Bycatch in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> Feeds and<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir Associated Problems 12<br />

Part 4: Moving Towards More<br />

Sustainable Feeds 15<br />

Part 5: Moving Towards Sustainable<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> Systems 16<br />

Part 6: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> Certificati<strong>on</strong> 17<br />

Part 7: Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s 18<br />

Footnotes 20

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

01<br />

©GREENPEACE / M CARE<br />

image Bluefin tuna swim inside a<br />

transport cage.<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> is taking acti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

threats to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sea and calling for a<br />

network of large-scale marine reserves<br />

to protect <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> health and productivity of<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mediterranean Sea.<br />

4 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

image Fish farm,<br />

Loch Harport,<br />

Scotland.<br />

©GREENPEACE / R REEVE<br />

The farming of aquatic plants and animals is known as<br />

aquaculture and has been practised for around 4000 years in<br />

some regi<strong>on</strong>s of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> world 1 . Since <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mid-1980s, however,<br />

producti<strong>on</strong> of fish, crustaceans and shellfish by aquaculture<br />

has grown massively (Figure 1). Globally, aquacultural<br />

producti<strong>on</strong> has become <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fastest growing food producti<strong>on</strong><br />

sector involving animal species. About 430 (97%) of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

aquatic species presently in culture have been domesticated<br />

since <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> start of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 20th century 2 and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number of aquatic<br />

species domesticated is still rising rapidly. It was recently<br />

estimated that aquaculture provides 43% of all <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fish<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sumed by humans today 3 .<br />

The landings of fish from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> world’s oceans have gradually declined<br />

in recent years as stocks have been progressively overfished 4 . At <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

same time, demand for seafood has been steadily rising and, in<br />

parallel, aquaculture producti<strong>on</strong> has expanded significantly. This<br />

expansi<strong>on</strong> is both a resp<strong>on</strong>se to increasing demand for seafood and,<br />

especially in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> case of luxury products such as salm<strong>on</strong> and shrimp,<br />

an underlying cause of that rising demand (see figure 1).<br />

The animal species that tend to dominate world aquaculture are<br />

those at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lower end of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> food chain – shellfish, herbivorous fish<br />

(plant-eating) and omnivorous fish (eating both plants and animals),<br />

(see figure 2). For example, carp and shellfish account for a<br />

significant share of species cultivated for human c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> in<br />

developing countries 5 . However, producti<strong>on</strong> of species higher in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

food chain, such as shrimp, salm<strong>on</strong>, and marine finfish, is now<br />

growing, in resp<strong>on</strong>se to a ready market for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se species in<br />

developed countries 3,5 .<br />

Figure 1. Global Fish Harvest, Marine Capture Fisheries and<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g>, 1950-2005.<br />

200<br />

150<br />

Milli<strong>on</strong> T<strong>on</strong>nes<br />

100<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

50<br />

Marine Capture<br />

0<br />

1950<br />

1960<br />

1970<br />

1980<br />

1990<br />

2000<br />

Source: FAO.<br />

Table 1. World <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> Producti<strong>on</strong> For The Years 2000 to 2005<br />

World Producti<strong>on</strong><br />

(Milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes) 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005<br />

Marine <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> 14.3 15.4 16.5 17.3 18.3 18.9<br />

Freshwater <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> 21.2 22.5 23.9 25.4 27.2 28.9<br />

Source: Adapted from FAO 3 .<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> 5

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Against a c<strong>on</strong>tinuing background of diminishing and over–exploited<br />

marine resources, aquaculture has been widely held up as a panacea to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> problem of providing a growing world populati<strong>on</strong> with ever-increasing<br />

amounts of fish for c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong>. With <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> expansi<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry,<br />

however, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> tendency has been for methods of producti<strong>on</strong> to intensify,<br />

particularly in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> producti<strong>on</strong> of carnivorous species. This has resulted in<br />

many serious impacts <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> envir<strong>on</strong>ment and human rights abuses.<br />

A more extensive and fully referenced versi<strong>on</strong> of this report can be<br />

downloaded at: www.greenpeace.org/aquaculture_report<br />

This report examines some of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> serious envir<strong>on</strong>mental and social<br />

impacts that have resulted from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> development and practice of<br />

aquaculture and which are reflected across <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> global industry. It starts<br />

by looking at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> producti<strong>on</strong> of salm<strong>on</strong>, tuna, o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r marine finfish, shrimp<br />

and tilapia. These case studies serve to illustrate a number of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se<br />

envir<strong>on</strong>mental and social problems, which toge<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r undermine <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

sustainability of c<strong>on</strong>temporary aquaculture (Secti<strong>on</strong> 2). Negative social<br />

impacts have been associated with both <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> producti<strong>on</strong> and processing<br />

industries in developing countries. Abuses stem from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> desire of<br />

producers and processors to maximise profits within a highly competitive<br />

market, while meeting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> low prices demanded by c<strong>on</strong>sumers (Secti<strong>on</strong><br />

2). The use of fishmeal and fish oil as feed in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> producti<strong>on</strong> of some<br />

species is a key issue (Secti<strong>on</strong> 3). O<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r negative envir<strong>on</strong>mental impacts<br />

can be addressed in a variety of ways in order to place aquaculture <strong>on</strong> a<br />

more sustainable footing (Secti<strong>on</strong> 4 and 5). Secti<strong>on</strong> 6 briefly explores<br />

certificati<strong>on</strong> of aquaculture products. Ultimately, aquaculture must<br />

become sustainable. In order to achieve this, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> aquaculture industry<br />

will need to adopt and adhere to rigorous standards (Secti<strong>on</strong> 7).<br />

Figure 2 Global aquaculture producti<strong>on</strong> pyramid by feeding habit and nutrient supply in 2003<br />

CARNIVOROUS FINFISH<br />

3.98 milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes – 7.3%<br />

OMNIVOROUS/SCAVENGING<br />

CRUSTACEANS<br />

2.79 milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes – 5.1%<br />

HERBIVOROUS/OMNIVOROUS/<br />

FILTER FEEDING FINFISH, MOLLUSCS<br />

AQUATIC PLANTS<br />

47.84 milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes – 87.6%<br />

CARNIVOROUS<br />

FINFISH<br />

CRUSTACEA<br />

OMNIVOROUS/<br />

HERBIVOROUS FINFISH<br />

16.02 milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes – 29.2%<br />

FILTER FEEDING FINFISH<br />

7.04 milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes – 12.8%<br />

FILTER FEEDING MOLLUSCS<br />

12.30 milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes – 22.4%<br />

PHOTOSYNTHETIC AQUATIC PLANTS<br />

12.48 milli<strong>on</strong> t<strong>on</strong>nes – 22.8%<br />

Source: FAO 52<br />

6 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

Negative Impacts of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> People and <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment<br />

02<br />

©GREENPEACE / C SHIRLEY<br />

image <strong>Greenpeace</strong> & locals replant<br />

mangroves that had been cut for<br />

shrimp farming, Ecuador.<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> 7

Negative Impacts of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> People and <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment<br />

The following case studies of negative impacts of aquaculture are far<br />

from exhaustive. Ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y provide examples that illustrate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wide<br />

spectrum of problems associated with aquacultural activities, and<br />

cast serious doubts <strong>on</strong> industry claims of sustainability.<br />

2.1 SHRIMP<br />

Destructi<strong>on</strong> of Habitat: The creati<strong>on</strong> of p<strong>on</strong>ds for marine shrimp<br />

aquaculture has led to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> destructi<strong>on</strong> of thousands of hectares of<br />

mangroves and coastal wetlands. Significant losses of mangroves<br />

have occurred in many countries including <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Philippines 6 , Vietnam 7 ,<br />

Thailand 8 , Bangladesh 9 and Ecuador 10 .<br />

Mangroves are important because <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y support numerous marine as<br />

well as terrestrial species, protect coastlines from storms and are<br />

important in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> subsistence of many coastal communities.<br />

Mangroves provide nursery grounds for various young aquatic<br />

animals including commercially important fish, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir destructi<strong>on</strong><br />

can lead to substantial losses for commercial fisheries 11,12 .<br />

Collecti<strong>on</strong> of Wild Juveniles as Stock<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> of some species relies <strong>on</strong> juvenile fish or shellfish being<br />

caught from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild to stock culture p<strong>on</strong>ds. For example, even<br />

though hatchery-raised shrimp c<strong>on</strong>stitute a major supply of shrimp<br />

juveniles (scientifically called “postlarvae”) to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> aquaculture industry,<br />

shrimp farms in many parts of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> world are still based <strong>on</strong> wild-caught<br />

juveniles. Some natural stocks of shrimp are now over-exploited as a<br />

result of juveniles collecti<strong>on</strong> from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild 13,14 . Fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rmore, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

juvenile shrimp may <strong>on</strong>ly represent a small fracti<strong>on</strong> of each catch, with<br />

a large incidental catch (by-catch) and mortality of o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species<br />

taking place (see text box 1). This poses serious threats to regi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

biodiversity and reduces food available to o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species such as<br />

aquatic birds and reptiles.<br />

Box 1 Loss of o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> collecti<strong>on</strong><br />

of wild shrimp juveniles<br />

• In Bangladesh, for each tiger shrimp juvenile collected <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were<br />

12–551 shrimp larvae of o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species caught and killed,<br />

toge<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r with 5–152 finfish larvae and 26–1636<br />

macrozooplankt<strong>on</strong>ic animals.<br />

• In H<strong>on</strong>duras, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> reported annual collecti<strong>on</strong> of 3.3 billi<strong>on</strong> shrimp<br />

juveniles resulted in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> destructi<strong>on</strong> of an estimated 15–20 billi<strong>on</strong><br />

fry of o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species 13 .<br />

Chemicals used to C<strong>on</strong>trol Diseases<br />

A wide variety of chemicals and drugs may be added to aquaculture<br />

cages and p<strong>on</strong>ds in order to c<strong>on</strong>trol viral, bacterial, fungal or o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r<br />

pathogens 16 . There is a risk that such agents may harm aquatic life<br />

nearby. The use of antibiotics also brings a potential risk to public<br />

health as over-use of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se drugs can result in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> development of<br />

antibiotic-resistance in bacteria that cause disease in humans.<br />

Studies <strong>on</strong> shrimp farms in Vietnam 17 and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Philippines 18 found<br />

bacteria had acquired resistance to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> antibiotics used <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> farms.<br />

Depleti<strong>on</strong> and Salinizsati<strong>on</strong> of Potable Water and Salinisati<strong>on</strong><br />

of Agricultural Land<br />

Intensive shrimp farming in p<strong>on</strong>ds requires c<strong>on</strong>siderable amounts of<br />

fresh water to maintain p<strong>on</strong>d water at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> optimum salinity for shrimp<br />

growth. Typically this involves pumping water from nearby rivers or<br />

groundwater supplies, and this may deplete local freshwater<br />

resources. Fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rmore, if aquifers are pumped excessively, salt water<br />

seeps in from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nearby sea causing salinisati<strong>on</strong> and making <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

water unfit for human c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> 19,20 . For example, in Sri Lanka,<br />

74% of coastal people in shrimp farming areas no l<strong>on</strong>ger have ready<br />

access to drinking water 21 . Shrimp farming can also cause increased<br />

soil salinity in adjacent agricultural areas, leading to declines in crops.<br />

For instance, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re are numerous reports of crop losses in Bangladesh<br />

caused by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> salinisati<strong>on</strong> of land, associated with shrimp farming 22 .<br />

Human Rights Abuses<br />

The positi<strong>on</strong>ing of shrimp farms has often blocked access to coastal<br />

areas that were <strong>on</strong>ce comm<strong>on</strong> land in use by many people. There is<br />

often a lack of formalised land rights and entitlements in such areas<br />

and this has led to large scale displacement of communities, often<br />

without financial compensati<strong>on</strong> or alternative land made available <strong>on</strong><br />

which to live (see text box 2).<br />

N<strong>on</strong>-violent protests against <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry have frequently been<br />

countered with threats and intimidati<strong>on</strong>. According to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Justice Foundati<strong>on</strong> 21 , violence has frequently been<br />

meted out by security pers<strong>on</strong>nel and “enforcers” associated with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

shrimp industry, many protesters have been arrested <strong>on</strong> false charges<br />

and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re are even reports from at least 11 countries of protesters<br />

being murdered (see figure 3). (In Bangladesh al<strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re have been<br />

an estimated 150 murders linked to aquaculture disputes.)<br />

Perpetrators of such violence are very rarely brought to justice.<br />

• In <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Indian Sundarbans, tiger shrimp juveniles <strong>on</strong>ly account for<br />

0.25–0.27% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> total catch. The rest of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> catch c<strong>on</strong>tains<br />

huge numbers of juvenile finfish and shellfish which are left aside<br />

<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> beach flats to die 15 .<br />

8 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

image Crabs ga<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>red<br />

from mangrove forest<br />

for sale at Gayaquil<br />

market, Ecuador.<br />

Mangrove ecology is<br />

endangered by cutting<br />

for shrimp farms.<br />

©GREENPEACE / D BELTRA<br />

Box 2 Case studies of land seizures for shrimp farm<br />

c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong><br />

• Some Ind<strong>on</strong>esian shrimp farms have been c<strong>on</strong>structed following<br />

forced land seizures in which companies, supported by police<br />

and government agencies, provided ei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r inappropriate<br />

compensati<strong>on</strong> or n<strong>on</strong>e at all. Such cases have been reported<br />

from Sumatra, Maluku, Papua and Sulawesi.<br />

• In Ecuador, reports indicate that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re have been thousands of<br />

forced land seizures, <strong>on</strong>ly 2% of which have been resolved <strong>on</strong> a<br />

legal basis. Tens of thousands of hectares of ancestral land have<br />

allegedly been seized. This has often involved use of physical<br />

force and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> deployment of military pers<strong>on</strong>nel 21 .<br />

• Between 1992-1998 in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Gulf of F<strong>on</strong>seca, H<strong>on</strong>duras, many<br />

coastal-dwelling people lost access to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir traditi<strong>on</strong>al food<br />

sources and access to fishing sites because of encroachment <strong>on</strong><br />

land by commercial shrimp-farming companies 23 .<br />

2.2 SALMON<br />

Nutrient Polluti<strong>on</strong><br />

Organic wastes from fish or crustacean farming include uneaten food,<br />

body wastes and dead fish 24 . In salm<strong>on</strong> farming, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se wastes enter<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> aquatic envir<strong>on</strong>ment in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> vicinity of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cages. In extreme cases<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> large numbers of fish present in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cages can generate sufficient<br />

waste to cause oxygen levels in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> water to fall, resulting in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

suffocati<strong>on</strong> of both wild and farmed fish. More usually, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> impacts of<br />

intensive salm<strong>on</strong> culture are seen in a marked reducti<strong>on</strong> in biodiversity<br />

around <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cages 25 . For example, a study in southwest New Brunswick<br />

found a reducti<strong>on</strong> in biodiversity <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> seabed up to 200 metres away from<br />

salm<strong>on</strong> cages 26 . In Chile, biodiversity close to eight salm<strong>on</strong> farms was<br />

reduced by at least 50%. Wastes can also act as plant nutrients and,<br />

in areas where water circulati<strong>on</strong> is restricted, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se may also lead to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rapid growth of certain species of phytoplankt<strong>on</strong> (microscopic<br />

algae) and filamentous algae 27 . Some of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> algal blooms which can<br />

result are very harmful: <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y can cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> death of a range of marine<br />

animals and also cause shellfish pois<strong>on</strong>ing in humans.<br />

Figure 3 Worldmap showing 11 countries where <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re has been murder associated with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> shrimp industry<br />

Countries include Mexico, Guatemala, H<strong>on</strong>duras, Ecuador, Brazil, India, Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam, Ind<strong>on</strong>esia and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Philippines.<br />

Source: Envir<strong>on</strong>mental Justice Foundati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> 9

Negative Impacts of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> People and <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment<br />

Threat to Wild Fish from escaped Farmed Salm<strong>on</strong><br />

Farmed Atlantic salm<strong>on</strong> have a lower genetic variability than wild<br />

Atlantic salm<strong>on</strong> 28,29 . Hence, if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y interbreed with wild salm<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

offspring may be less fit than wild salm<strong>on</strong> and genetic variability that is<br />

important for adaptability in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild may be lost. It was originally<br />

thought that escaped salm<strong>on</strong> would be less able to cope with<br />

c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s encountered in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild and would be unable to survive,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>reby not posing a threat to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> genetic diversity of wild<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s. In reality, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sheer numbers that have escaped (an<br />

estimated 3 milli<strong>on</strong> per year) 30 mean that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y are now breeding with<br />

wild salm<strong>on</strong> in Norway, Ireland, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> United Kingdom and North<br />

America. Because <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y produce offspring less able to survive in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

wild, this means that already vulnerable populati<strong>on</strong>s could be driven<br />

towards extincti<strong>on</strong>. In Norway, farmed salm<strong>on</strong> have been estimated to<br />

comprise 11–35% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> of spawning salm<strong>on</strong>; for some<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s this may rise to more than 80% 28 . C<strong>on</strong>tinuing escapes<br />

may mean that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> original genetic profile of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> will not<br />

re-assert itself 31 .<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong> to threats to wild Atlantic salm<strong>on</strong> caused by escapees in<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir native regi<strong>on</strong>s, farmed Atlantic salm<strong>on</strong> that have been introduced<br />

to Pacific streams pose a threat to o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r native fish populati<strong>on</strong>s, such<br />

as steelhead in North America and galaxiid fishes in South America,<br />

because <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y compete for food and habitat 28 .<br />

Diseases and Parasites<br />

Diseases and parasites can be particularly problematic in fish farming<br />

where stocking densities are high. Wild populati<strong>on</strong>s of fish passing<br />

near to farms may also be affected. One notable example is that of<br />

parasitic sea lice which feed <strong>on</strong> salm<strong>on</strong> skin, mucous and blood and<br />

which can even cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> death of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fish. There is evidence that<br />

wild salm<strong>on</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>s have been affected by lice spread from farms<br />

in British Columbia 32 and Norway 31 . Recent research in British<br />

Columbia suggests that sea lice infestati<strong>on</strong> resulting from farms will<br />

cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> local pink salm<strong>on</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>s to fall by 99% within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir<br />

next four generati<strong>on</strong>s 33 . If outbreaks c<strong>on</strong>tinue unchecked, extincti<strong>on</strong> is<br />

almost certain.<br />

Human Rights Issues<br />

In sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Chile <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> salm<strong>on</strong> farming industry has grown rapidly since<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> late 1980s to serve export markets in western nati<strong>on</strong>s 34,35 . In 2005,<br />

nearly 40% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> world’s farmed salm<strong>on</strong> was supplied from Chilean<br />

producers and processors 36 .<br />

This burge<strong>on</strong>ing industry has an appalling safety record. Poor or n<strong>on</strong>existent<br />

safety c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s have been widely reported <strong>on</strong> Chilean farms<br />

and in processing plants 35,36 . Over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> past three years <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re have<br />

been more than 50 accidental deaths, mostly of divers. By c<strong>on</strong>trast,<br />

no deaths have been reported in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Norwegian salm<strong>on</strong> industry, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

world’s largest producer of salm<strong>on</strong> 37 . Reports from Chile also tell of<br />

low wages (around <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nati<strong>on</strong>al poverty line), l<strong>on</strong>g working hours, lack<br />

of respect for maternity rights and persistent sexual harassment of<br />

women 35,36 .<br />

2.3 OTHER MARINE FINFISH<br />

Marine finfish aquaculture is an emerging industry. Improvements in<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> technology of salm<strong>on</strong> farming toge<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r with decreasing market<br />

prices for salm<strong>on</strong> have inspired <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry to start farming highervalue<br />

marine finfish species. Species which are now being farmed<br />

include (1) Atlantic cod in Norway, UK, Canada and Iceland; (2)<br />

haddock in Canada, Norway and nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>astern United States; (3)<br />

Pacific threadfin in Hawaii; (4) black sablefish under development in<br />

British Columbia and Washingt<strong>on</strong> State; (5) mutt<strong>on</strong> snapper; (6)<br />

Atlantic halibut; (7) turbot; (8) sea bass and (9) sea bream 5,28 . Most<br />

species are reared in net pens or cages like salm<strong>on</strong>, although Atlantic<br />

halibut and turbot are generally farmed in tanks <strong>on</strong> land.<br />

It is likely that envir<strong>on</strong>mental problems similar to those encountered in<br />

salm<strong>on</strong> farming will also manifest <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>mselves in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> farming of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se<br />

“new” marine species in cages. In some cases <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y could be worse.<br />

For example, cod produce c<strong>on</strong>siderably more waste than Atlantic<br />

salm<strong>on</strong> 28 leading to potential nutrient polluti<strong>on</strong>. Even if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> impacts of<br />

this can be reduced by siting cages some distance offshore where<br />

water movements are more vigorous, o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r impacts are still likely to<br />

result. As in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> case of salm<strong>on</strong> aquaculture, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se include a risk of<br />

disease spreading to wild populati<strong>on</strong>s and, if selectively bred, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re is<br />

a risk of escapees competing with wild fish and interbreeding with<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m, causing a reducti<strong>on</strong> in genetic variability.<br />

2.4 TUNA RANCHING – WIPING OUT BLUEFIN TUNA IN THE<br />

MEDITERRANEAN SEA<br />

The present level of fishing effort directed at nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn bluefin tuna in<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mediterranean threatens <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> future of this species in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> regi<strong>on</strong><br />

and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> future of hundreds of fishermen. There are serious c<strong>on</strong>cerns<br />

that commercial extincti<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> species may be just around <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

corner 38 .<br />

10 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

image Captive bluefin tuna<br />

inside a transport cage. The<br />

cage is being towed by a<br />

tug from fishing grounds in<br />

Libya to tuna farms in Sicily.<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> is calling<br />

<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> countries of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Mediterranean to protect<br />

bluefin tuna with marine<br />

reserves in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir breeding<br />

and feeding areas.<br />

©GREENPEACE / G NEWMAN<br />

In May 1999, <strong>Greenpeace</strong> released a report describing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> depleti<strong>on</strong><br />

of bluefin tuna in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mediterranean 39 . This noted that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> spawning<br />

stock biomass (total weight) of tuna was estimated to have decreased<br />

by 80% over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> previous 20 years. In additi<strong>on</strong>, huge amounts of<br />

juvenile tuna were being caught every seas<strong>on</strong>. <strong>Greenpeace</strong> reported<br />

that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> main threat to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bluefin tuna at that time was Illegal,<br />

Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing, also called “pirate fishing”.<br />

IUU fishing operates outside of management and c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> rules<br />

and, in effect, steals fish from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> oceans. It has become a serious<br />

and wide-ranging global problem, is a threat to marine biodiversity<br />

and a serious obstacle to achieving sustainable fisheries 40,41 .<br />

Seven years <strong>on</strong> in 2006, fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r analysis by <strong>Greenpeace</strong> showed that<br />

threats to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> tuna had worsened 38 . Pirate fishing c<strong>on</strong>tinued<br />

unabated, and was now fuelled by a new incentive of supplying tuna<br />

to an increasing number of tuna ranches in Mediterranean countries.<br />

In tuna ranching, fish are caught alive and grown <strong>on</strong> in cages with<br />

artificial feeding. The fattened fish are <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n killed and exported, mainly<br />

to Japan. Tuna ranching began in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> late 1990s and has boomed,<br />

spreading to 11 countries by 2006 (see figure 4). Today, due to poor<br />

management of tuna fisheries, nobody knows <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> exact numbers of<br />

tuna taken from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mediterranean Sea each year. N<strong>on</strong>e<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>less, it is<br />

clear that current catch levels are well above <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> legal quota. For<br />

example, it was estimated, based <strong>on</strong> 2005 figures, that over 44,000<br />

t<strong>on</strong>nes of tuna may have been caught in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mediterranean. This was<br />

37.5% over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> legally sancti<strong>on</strong>ed catch limit and, disturbingly, almost<br />

70% above <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> scientifically recommended maximum catch level. The<br />

total capacity of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> tuna ranches exceeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> total allowable catch<br />

quotas which exist to supply <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m. This is a clear incentive for illegal<br />

fishing in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> regi<strong>on</strong>. An examinati<strong>on</strong> of available trends in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry<br />

clearly indicates that illegal fishing for tuna is supplying ranches 38 .<br />

2.5 TILAPIA<br />

Introducti<strong>on</strong> of Alien Species<br />

When a species is released into an envir<strong>on</strong>ment where is it not native,<br />

it may reproduce successfully but have negative c<strong>on</strong>sequences <strong>on</strong><br />

native species 42 . Tilapia species provide a striking illustrati<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

problems that such releases can cause. Three species of tilapia are<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> most important in aquaculture: <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nile tilapia, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mozambique<br />

tilapia and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> blue tilapia 43 . These freshwater fish are native to Africa<br />

and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Middle East but over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> past 30 years <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir use in<br />

aquaculture has expanded and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y are now farmed in about 85<br />

countries worldwide. Presently, tilapia are sec<strong>on</strong>d <strong>on</strong>ly to carp as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

quantitatively most important farmed fish in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> world 44 . Tilapia have<br />

escaped from sites where <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y are cultured into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wider<br />

envir<strong>on</strong>ment, have successfully invaded new habitats and<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sequently have become a widely distributed exotic species.<br />

Once in a n<strong>on</strong>-native envir<strong>on</strong>ment, tilapia threaten native fish by<br />

feeding <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir juveniles as well as <strong>on</strong> plants that are habitat refuges<br />

for juveniles. Negative impacts of tilapia invasi<strong>on</strong>s into n<strong>on</strong>-native<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>s have been widely reported and include:<br />

1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> decline of an endangered fish species in Nevada and Ariz<strong>on</strong>a,<br />

2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> decline of a native fish in Madagascar,<br />

3 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> decline of native cichlid species in Nicaragua and in Kenya, and<br />

4 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> breeding of escaped tilapia in Lake Chichincanab, Mexico to<br />

become <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> dominant species 44 at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cost of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> native fish<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Figure 4 Tuna farming proliferati<strong>on</strong><br />

1985 1996 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2006<br />

Spain Spain Spain Spain Spain Spain Spain Spain<br />

Croatia Croatia Croatia Croatia Croatia Croatia Croatia<br />

Malta Malta Malta Malta Malta Malta<br />

Italy Italy Italy Italy Italy<br />

Turkey Turkey Turkey Turkey<br />

Cyprus Cyprus Cyprus<br />

Libya Libya Libya<br />

Source: Lovatelli, A. 2005. Summary Report <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> status of BFT aquaculture in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mediterranean. FAO Fisheries Report No 779 and ICCAT database <strong>on</strong> declared farming facilities, available <strong>on</strong>line at<br />

www.iccat.es/ffb.asp<br />

Greece<br />

Leban<strong>on</strong><br />

Greece<br />

Tunisia<br />

Morocco<br />

Portugal<br />

Leban<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> 11

Use of Fishmeal/Fish Oil/Bycatch<br />

in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> Feeds and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir Associated Problems<br />

03<br />

©GREENPEACE / G NEWMAN<br />

image Salm<strong>on</strong> run at Annan Creek in<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> T<strong>on</strong>gass Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest, Alaska.<br />

12 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> Standards <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

image View from<br />

above of people<br />

sorting shrimps<br />

<strong>on</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g tables,<br />

Muisne, Ecuador<br />

©GREENPEACE / C SHIRLEY<br />

Fishmeal and fish oil used in aquaculture feeds are largely derived<br />

from small oily fish such as anchovies, herrings and sardines (larger<br />

sardines are also known as pilchards), taken in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> so-called<br />

“industrial fisheries”. As aquaculture methods have intensified, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<br />

has been a growing dependence <strong>on</strong> fishmeal/oil as a feed source.<br />

The farming of carnivorous species in particular is highly dependent<br />

<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> use of fishmeal and fish oil, in syn<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>tic diets used to simulate<br />

natural prey taken as food in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild.<br />

Farming Carnivores – A Net Loss of Protein….<br />

The aquaculture industry has c<strong>on</strong>sistently promoted <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> idea that its<br />

activities are key to assuring future sustainable world fish supplies and<br />

will relieve pressures <strong>on</strong> over-exploited marine resources. In fact, in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

case of carnivorous fish and shrimp <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> input of wild caught fish<br />

exceeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> output of farmed fish by a c<strong>on</strong>siderable margin, since<br />

c<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> efficiencies are not high. For example, each kilogram of<br />

salm<strong>on</strong>, o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r marine finfish or shrimp produced may use 2.5–5 kg of<br />

wild fish as feed 45 . For tuna ranching, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ratio of wild fish needed as<br />

feed to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount of tuna fish produced is even higher – 20 kg fishfeed<br />

to 1 kg farmed fish 46 . Thus, farming of carnivorous species results<br />

in a net loss ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than a net gain of fish protein. Instead of alleviating<br />

pressure <strong>on</strong> wild fish stocks, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>refore, aquaculture of carnivorous<br />

species increases pressure <strong>on</strong> wild stocks of fish, albeit of different<br />

species. With fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r intensificati<strong>on</strong> of aquaculture and expansi<strong>on</strong> of<br />

marine finfish aquaculture, it is likely that demand for fishmeal and fish<br />

oil will even outstrip <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> current unsustainable supply.<br />

Unsustainable Fisheries….<br />

Many global marine fisheries are currently exploited in an<br />

unsustainable manner, and this includes industrial fisheries. C<strong>on</strong>cerns<br />

extend to o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r marine species because fish taken by industrial<br />

fishers play a vital role in marine ecosystems. They are prey for many<br />

o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r fish species (including commercially important species), marine<br />

mammals and sea birds. Overfishing of industrially fished species has<br />

led to negative impacts <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> breeding success of some seabirds<br />

(see text box 3).<br />

Box 3 Negative impacts of industrial fisheries <strong>on</strong> seabirds<br />

• In <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> late 1960s <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Norwegian spring-spawning herring stock<br />

collapsed due to over fishing. Stocks c<strong>on</strong>tinued to remain low<br />

between 1969 and 1987 and this severely impacted <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> breeding<br />

success of Atlantic puffins due to lack of food 50 .<br />

• Overfishing of North Sea sandeel stocks in recent years has had a<br />

negative impact <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> breeding success of black-legged<br />

kittiwakes 51 . Closure of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fishery east of Scotland was<br />

recommended from 2000–2004 to safeguard <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se birds and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

local populati<strong>on</strong> of puffins.<br />

A specific assessment of several important industrially fished species<br />

c<strong>on</strong>cluded that, for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> most part, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fisheries were entirely<br />

unsustainable 47 . O<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r research has shown that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fisheries must be<br />

regarded as fully exploited or over-exploited 48,49 . C<strong>on</strong>sequently, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re<br />

is a crucial need for aquaculture to reduce its dependence <strong>on</strong><br />

fishmeal and fish oil.<br />

Demands for Fishmeal and Fish Oil in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g>…..<br />

The quantity of fishmeal and fish oil used by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> aquaculture industry<br />

has increased over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> years as aquaculture has expanded and<br />

intensified. In 2003, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry used 53% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> total world’s<br />

fishmeal producti<strong>on</strong> and 86% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> world’s fish oil producti<strong>on</strong> 5,52 . The<br />

increased demand for fishmeal and fish oil by aquaculture has been<br />

met by diverting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se products away from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir use as feed for<br />

agricultural animals, in itself a c<strong>on</strong>troversial issue. Currently,<br />

agricultural use of fishmeal and fish oil is increasingly restricted to<br />

starter and breeder diets for poultry and pigs. Fish oil previously used<br />

in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> manufacture of hard margarines and bakery products has now<br />

been largely diverted to aquacultural use 53 . Figure 5 depicts <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

estimated global use of fishmeal within compound aquafeeds in 2003<br />

by major species.<br />

Although a trend has emerged in recent years of replacing fishmeal<br />

with plant-based proteins in aquaculture feeds, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fracti<strong>on</strong> of<br />

fishmeal/oil used for diets of carnivorous species remains high.<br />

Moreover, this trend has not been fast enough to offset <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> growing<br />

use of fishmeal, caused simply by an increase in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> overall number of<br />

farmed carnivorous fish produced. For example, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> quantity of wild<br />

fish required as feed to produce <strong>on</strong>e unit of farmed salm<strong>on</strong> reduced<br />

by 25% between 1997 and 2001, but <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> total producti<strong>on</strong> of farmed<br />

salm<strong>on</strong> grew by 60% 5 , eclipsing much of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> improvement in<br />

c<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> efficiencies.<br />

Figure 5 Estimated global use of fishmeal within compound<br />

aquafeeds in 2003.<br />

Marine Shrimp 22.8%<br />

Marine Fish 20.1%<br />

Trout 7.4%<br />

Salm<strong>on</strong> 19.5%<br />

Eel 5.8%<br />

Milkfish 1.2%<br />

Carp 14.9%<br />

Tilapia 2.7%<br />

Catfish 0.8%<br />

Freshwater<br />

Crustaceans 4.7%<br />

Source: FAO 52<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> 13

Use of Fishmeal/Fish Oil/Bycatch<br />

in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> Feeds and Associated Problems<br />

Food Security Issues….<br />

The use of fishmeal and fish oil derived from marine species of fish for<br />

aquaculture also has implicati<strong>on</strong>s for human food security. For<br />

example, in Sou<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ast Asia and Africa, small pelagic (open water) fish<br />

such as those targeted by industrial fisheries are important in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

human diet 54 . Demand for such fish is likely to grow as populati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

increase, bringing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m under pressure both from aquaculture and<br />

direct c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> 55 . In additi<strong>on</strong>, low value fish (inappropriately<br />

termed “trash fish”) caught as by-catch and used for fishmeal<br />

producti<strong>on</strong> are actually an important food source for poorer people in<br />

developing countries 56 . Use of “trash fish” in aquaculture inflates<br />

prices such that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rural poor can no l<strong>on</strong>ger afford to buy it 52 . With<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se factors in mind, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> UN Food and Agricultural Organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

(FAO) has recommended that governments of major aquacultureproducing<br />

countries prohibit <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> use of “trash fish” as feed for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

culture of high value fish.<br />

©GREENPEACE / K DAVISON<br />

image Catch landed <strong>on</strong> board EU<br />

bottom-trawler, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ivan Nores, in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Hatt<strong>on</strong> Bank area of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> North Atlantic,<br />

410 miles north-west of Ireland.<br />

Bottom-trawling boats, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> majority<br />

from EU countries, drag fishing gear<br />

weighing several t<strong>on</strong>nes across <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sea<br />

bed, destroying marine wildlife and<br />

devastating life <strong>on</strong> underwater<br />

mountains - or 'seamounts'.<br />

14 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

Moving Towards<br />

More Sustainable Feeds<br />

04<br />

©GREENPEACE / G NEWMAN<br />

image Turkish tuna fleet Purse Seine<br />

fishing and transfering catch to<br />

transport cage.<br />

The aquaculture industry is highly dependent up<strong>on</strong> wild caught fish to<br />

manufacture feed for cultured species. This is widely recognised as an<br />

intensive and generally unsustainable use of a finite resource. In turn,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry has recognised <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> need to evaluate and use more plantbased<br />

feed materials and reduce dependence <strong>on</strong> fishmeal and fish oil.<br />

Plants are already used in aquaculture feeds. Those that are used<br />

and/or show particular promise for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> future include soybean, barley,<br />

canola, corn, cott<strong>on</strong>seed and pea/lupin 57 . It is important to note that if<br />

plant-based feeds are used in aquaculture, to be sustainable <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y<br />

must be sourced from agriculture that is sustainable. Sustainable<br />

agriculture by definiti<strong>on</strong> precludes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> use of any genetically modified<br />

crops. These crops are associated with a number of potential<br />

envir<strong>on</strong>mental impacts, genetic c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong> of n<strong>on</strong>-GE crops and<br />

have also sparked a number of food-safety c<strong>on</strong>cerns which remain<br />

unresolved 58 .<br />

For some herbivorous and omnivorous fish, it has been possible to<br />

replace completely any fishmeal in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> diet with plant-based<br />

feedstuffs without impacts <strong>on</strong> fish growth and yield 52 . Rearing such<br />

species in this way suggests a more sustainable future path for<br />

aquaculture provided that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> feeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>mselves are produced<br />

through sustainable agriculture.<br />

Feeding of carnivorous species seems to be more problematic.<br />

Fishmeal and fish oil can be reduced by at least 50% in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> diet, but<br />

complete substituti<strong>on</strong> for plant ingredients has not yet been possible<br />

for commercial producti<strong>on</strong>. Problems include <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> presence of certain<br />

compounds in plants that are not favourable to fish, known as antinutriti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

factors, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lack of certain essential (omega-3) fatty<br />

acids 29,52 . Oily fish is c<strong>on</strong>sidered to be an important source of omega-<br />

3 fatty acids in human nutriti<strong>on</strong>, but feeding fish with plant oil-based<br />

diets al<strong>on</strong>e reduces <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir flesh. Recent research,<br />

however, has found that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fish oil input could be reduced by feeding<br />

fish with plant oils but switching to fish oils in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> period just prior to<br />

slaughter 59 . Recent research <strong>on</strong> marine shrimp suggests that it may<br />

be possible to replace fishmeal in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> diet largely with plant-based<br />

ingredients, although fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r study is needed 60,61 .<br />

Some aquaculture, particularly that classified as “organic”, uses fish<br />

trimmings as feed – offcuts of fish from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> filleting and processing of<br />

fish for human c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong>. This is more sustainable than using<br />

normal fishmeal in that a waste product is being used. However,<br />

unless <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fishery from which <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fish trimmings come from is itself<br />

sustainable, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> use of fish trimmings cannot be seen as sustainable<br />

because it perpetuates <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cycle of over-exploitati<strong>on</strong> of fisheries.<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> 15

Moving Towards<br />

Sustainable <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> Systems<br />

05<br />

©GREENPEACE / A SALAZAR<br />

image Aerial views of shrimp farms al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> coast of Tugaduaja, Chanduy near Guayaquil in Ecuador.<br />

In order for aquaculture operati<strong>on</strong>s to move towards sustainable<br />

producti<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry needs to recognise and address <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> full<br />

spectrum of envir<strong>on</strong>mental and societal impacts caused by its<br />

operati<strong>on</strong>s. Essentially, this means that it will no l<strong>on</strong>ger be acceptable<br />

for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry to place burdens of producti<strong>on</strong>, (such as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> disposal<br />

of waste) <strong>on</strong>to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wider envir<strong>on</strong>ment.<br />

In turn, this implies moving towards closed producti<strong>on</strong> systems. For<br />

example, in order to prevent nutrient polluti<strong>on</strong>, ways can be found to<br />

use nutrients present in waste products beneficially. Examples include<br />

integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) (see text box 4),<br />

aquap<strong>on</strong>ics and integrated rice-fish culture.<br />

Box 4 Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems (IMTA)<br />

In IMTA systems, organic waste products from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fed species<br />

(finfish or shrimp) are used as food by o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r cultivated species<br />

such as seaweed and shellfish. For example, at a commercial IMTA<br />

farm in Israel, marine fish (gil<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ad seabream) are farmed and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir<br />

nutrient-rich waste is used to grow seaweed. In turn, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> seaweed<br />

is used to feed Japanese abal<strong>on</strong>e which can be sold<br />

commercially 62 . In o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r systems being developed, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> seaweed<br />

itself may be commercially viable 63,64 .<br />

In aquap<strong>on</strong>ics systems, effluents from fish farming are used as a<br />

nutrient source for growing vegetables, herbs and/or flowers. One<br />

existing commercially viable aquap<strong>on</strong>ics system involves <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

cultivati<strong>on</strong> of tilapia in land-based tanks from which <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> waste water is<br />

used to grow vegetables (without soil) in greenhouses 65 . A company<br />

in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ne<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rlands called ‘Happy Shrimp’ partially use waste from<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir farms to grow vegetables. The shrimp are fed <strong>on</strong> algae and<br />

bacteria as well as <strong>on</strong> aquaculture feed c<strong>on</strong>taining a high proporti<strong>on</strong><br />

of plant protein. The shrimp are cultivated in greenhouses<br />

and no shrimp juveniles are extracted from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild 66 .<br />

In integrated rice–fish culture, fish are cultivated al<strong>on</strong>gside rice, which<br />

optimises use of both land and water. The nitrogen-rich fish excretory<br />

products fertilise <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rice, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fish also c<strong>on</strong>trol weeds and pests<br />

by c<strong>on</strong>suming <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m as food. Much of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fish nutriti<strong>on</strong> is derived<br />

naturally in this way. Major c<strong>on</strong>straints to widespread use of such<br />

methods include <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fact that many farmers are not educated in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

required skills 67 . This could be overcome if policy makers gave active<br />

support to this practice. Integrated rice–fish culture is crucial for local<br />

food security ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than for supplying export markets.<br />

16 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Certificati<strong>on</strong><br />

06<br />

©GREENPEACE / D BELTRA<br />

image Shrimps.<br />

The growth of aquaculture has led to a multiplicity of c<strong>on</strong>cerns<br />

attached to envir<strong>on</strong>mental impacts, social impacts, food safety,<br />

animal health and welfare and ec<strong>on</strong>omic/financial issues. All of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se<br />

factors influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sustainability of a given aquaculture system.<br />

Presently, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re are a growing number of certificati<strong>on</strong> schemes which<br />

seek to reassure buyers, retailers and c<strong>on</strong>sumers about various of<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se c<strong>on</strong>cerns. Currently existing certificati<strong>on</strong> schemes, however, do<br />

not cover all of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se issues and can sometimes present a c<strong>on</strong>fusing<br />

and c<strong>on</strong>flicting picture to retailers and c<strong>on</strong>sumers. A recent analysis of<br />

18 aquaculture certificati<strong>on</strong> schemes by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> World Wildlife Fund<br />

(WWF) showed that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y generally had major shortcomings in terms<br />

of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> way in which <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y c<strong>on</strong>sidered envir<strong>on</strong>mental standards and<br />

social issues 68 .<br />

The WWF report sets out benchmark criteria <strong>on</strong> envir<strong>on</strong>mental,<br />

social and animal welfare issues in aquaculture. The FAO has also<br />

recently published a document which covers many of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> relevant<br />

issues and could be used as a guide by certificati<strong>on</strong> bodies 69 . Any<br />

certificati<strong>on</strong> process, as an absolute minimum, needs to c<strong>on</strong>form to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se FAO guidelines. N<strong>on</strong>e<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>less, certificati<strong>on</strong> criteria al<strong>on</strong>e will<br />

not ensure <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sustainability of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> aquaculture industry worldwide.<br />

In order to do so, a more fundamental rethink and restructuring of<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry is essential.<br />

<strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> 17

Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

07<br />

©GREENPEACE / C SHIRLEY<br />

image Aerial view of damned p<strong>on</strong>ds<br />

with intact mangroves visible <strong>on</strong> lower<br />

left, bay of Guayaquil, Ecuador.<br />

18 <strong>Greenpeace</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al <str<strong>on</strong>g>Challenging</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Aquaculture</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong>

image Mock up picture of salm<strong>on</strong>,<br />

which will be 37 times bigger than<br />

normal, when genetically engineered.<br />

©GREENPEACE / J NOVIS<br />

Any aquaculture that takes place needs to be sustainable and fair.<br />

For aquaculture systems to be sustainable, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y must not lead to<br />

natural systems being subject to degradati<strong>on</strong> caused by:<br />

1 an increase in c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of naturally occurring substances,<br />

2 an increase in c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of substances, produced by society,<br />

such as persistent chemicals and carb<strong>on</strong> dioxide and<br />

3 physical disturbance.<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong> people should not be subject to c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s that<br />

systematically undermine <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir capacity to meet <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir basic needs for<br />

food, water and shelter.<br />

In practical terms, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se four c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s can be translated into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

following recommendati<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

Use of Fishmeal, Fish oil and “Trash Fish”: To reduce <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

pressure <strong>on</strong> stocks caught for fishmeal and fish oil, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re needs to be<br />

a c<strong>on</strong>tinued move towards sustainably produced plant-based feeds.<br />

Cultivating fish that are lower down <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> food chain (herbivores and<br />

omnivores ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than top predators) that can be fed <strong>on</strong> plant-based<br />

diets is key to achieving sustainable aquaculture practices. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Industry</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

must expand its research and development <strong>on</strong> herbivorous and<br />

omnivorous fish which have str<strong>on</strong>g market potential and suitability<br />

for farming.<br />

In more general terms, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re is an urgent need for fisheries<br />

management to shift towards an ecosystem-based approach wherein<br />

a global network of fully protected marine reserves covering 40% of<br />