Fiji Health Sector Situational Analysis 2008 - Pacific Health Voices

Fiji Health Sector Situational Analysis 2008 - Pacific Health Voices

Fiji Health Sector Situational Analysis 2008 - Pacific Health Voices

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

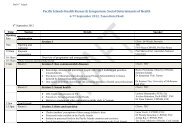

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

A SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE<br />

FIJI HEALTH SECTOR<br />

DECEMBER <strong>2008</strong><br />

1

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

1. INTRODUCTION 1<br />

1.1. Background 1<br />

1.2. Objectives and Methodology used for this <strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> 1<br />

2. THE FIJI SETTING 2<br />

2.1. <strong>Fiji</strong> - Demographic and Country overview. 2<br />

2.2. Economic and Political Situation. 3<br />

3. ORGANISATION, STAFFING AND FUNDING OF THE HEALTH SYSTEM. 4<br />

3.1. Overview of the MoH, its structure and organisation 4<br />

3.2. The Service Delivery Framework – a traditional model 4<br />

3.3. Staffing the <strong>Health</strong> System 6<br />

3.4. Financing the health system 10<br />

3.5. Planning and Managing the <strong>Health</strong> Care system, 16<br />

4. THE HEALTH OF THE PEOPLE OF FIJI. 17<br />

4.1. Key health Indicators 17<br />

4.2. Comparison with <strong>Pacific</strong> neighbours. 18<br />

4.3. Morbidity and Mortality. 18<br />

4.4. Key Lifestyle and other issues impacting on health of the people 20<br />

5. KEY ISSUES ARISING FROM THIS SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 21<br />

5.1. Perception of the health services by the public. 22<br />

5.2. Changes in demographics and social behaviour require a rethink of the location, staffing and range of<br />

services provided by health facilities. 23<br />

5.3. Relatively Poor progress towards Achievement of <strong>Fiji</strong>’s MDGs and other designated KPIs. 25<br />

5.4. Old or non-functioning equipment impacts on service delivery 29<br />

5.5. Stock Outs of Essential drugs 30<br />

5.6. The importance of more focused planning and better use of management information systems. 31<br />

5.7. The health sector should be seen as being more than just the MoH. 32<br />

i

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

5.8. The Need for an Evidence based approach to Policy and Planning. 34<br />

6. POSSIBLE AREAS FOR ASSISTANCE BY DEVELOPMENT PARTNERS. 34<br />

6.1. Overview 34<br />

6.2. Highest Priority Areas for AusAID Support. 35<br />

6.3. Other Possible Areas for support by AusAID and other donors. 37<br />

ii

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

LIST of TABLES<br />

Table<br />

Table 1. 2004-5 survey of population by age and ethnicity 2<br />

Table 2. Distribution of <strong>Health</strong> Facilities by Division 5<br />

Table 3. Doctor and Nurse to Population Ratio by Division 2004 6<br />

Table 4. MoH Medical Cadre as at 31/10/08 7<br />

Table 5. ‘Exit’ of staff from MoH over 5 years (2003-7) 9<br />

Table 6. GDP, MoH budget and MoH budget as % of GDP, 1993-2005 11<br />

Table 7. Govt. budget, MoH allocation and budget share, MoH revenue, MoH<br />

revenue as proportion of expenditure and Per-Capita <strong>Health</strong> Expenditure 1986-<br />

2006<br />

Table 8. Pharmaceutical Budget (millions FJD) 2003-<strong>2008</strong> 12<br />

Table 9. MOH Biomedical budget allocations 2003-<strong>2008</strong> 13<br />

Table 10. Examples of main areas of support provided to the health sector<br />

through development partners<br />

Table 11. <strong>Fiji</strong>’s Key <strong>Health</strong> Indicators 17<br />

Table 12. Selected regional comparative indicators 17<br />

Table 13. The Ten major causes of Morbidity and Mortality in 2007 18<br />

Table 14. Major causes of Mortality by diagnostic group 1998-2001 and 2005 18<br />

Table 15. Major causes of Morbidity by diagnostic group 1998-2001 and 2005 18<br />

Table 16. <strong>Fiji</strong>’s MDG Targets by 2015 25<br />

Table 17. Progress towards achievement of MDGs 4 and 5 26<br />

Table 18. Trimester of First Antenatal visits 26<br />

Page<br />

12<br />

14<br />

iii

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

ACRONOMYS<br />

ADB<br />

AIDS<br />

AusAID<br />

CCF<br />

CSPF<br />

CWM<br />

EPI<br />

EU<br />

FHMR<br />

FJD<br />

FSMed<br />

FHSIP<br />

FSN<br />

DP<br />

GOA<br />

HDI<br />

HIV<br />

HMD<br />

HRH<br />

HMIS<br />

HRH<br />

IGOF<br />

IT<br />

JICA<br />

KPI<br />

MBBS<br />

MDG<br />

MCH<br />

M and E<br />

MOF& NP<br />

MMR<br />

MoH<br />

MOU<br />

NCD<br />

NGO<br />

NZAID<br />

PATIS<br />

PC &SS<br />

PDD<br />

PEP<br />

PET<br />

PIC<br />

PNG<br />

PO<br />

PPH<br />

PSC<br />

SPC<br />

SOPAC<br />

Asian Development Bank<br />

Acquired Immune deficiency Syndrome<br />

Australian Agency for International Development<br />

Consumer Council of <strong>Fiji</strong><br />

Clinical Services Planning Framework<br />

Colonial War memorial Hospital (Suva)<br />

Expanded Program on Immunisation<br />

European Union<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> management Reform Project<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> Dollar<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> school of Medicine<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Services Improvement Program<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> School of Nursing<br />

Gross Domestic Product<br />

Government of Australia<br />

Human Development Index of the UN<br />

Human Immunodeficiency Virus<br />

Hylanine Membrane Disease<br />

Human Resources for <strong>Health</strong><br />

<strong>Health</strong> management Information system<br />

Human Resources for <strong>Health</strong><br />

Interim Government of <strong>Fiji</strong><br />

Information Technology<br />

Japan International Cooperation Agency<br />

Key Performance Indicator<br />

Bachelor of Medicine Bachelor of Surgery<br />

Millennium Development Goals<br />

Maternal and Child <strong>Health</strong><br />

Monitoring and Evaluation<br />

Ministry of Finance and national Planning<br />

Maternal Mortality Rate<br />

Ministry of <strong>Health</strong><br />

Memorandum of Understanding<br />

Non Communicable Disease<br />

Non Government Organisation<br />

New Zealand Agency for International Development<br />

Patient Information system<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> Counselling and Social Services<br />

Project Design Document<br />

Performance Enhancing Project<br />

Pre eclamptic toxaemia<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> Island Country<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Project Officer<br />

post partum haemorrhage<br />

Public Service Commission<br />

Secretariat for the <strong>Pacific</strong> Community<br />

South <strong>Pacific</strong> Applied Geosciences Commission<br />

iv

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

TB<br />

TOR<br />

UN<br />

UNAIDS<br />

UNDP<br />

UNFPA<br />

UNICEF<br />

USP<br />

WHO<br />

Tuberculosis (the disease)<br />

Terms of Reference<br />

United National<br />

United Nations Program on HIV&AIDS<br />

United Nations Development Program<br />

United Nation Family Planning Agency<br />

United Nations Children Program<br />

University of the South <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

World <strong>Health</strong> Organisation<br />

v

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

Introduction<br />

The health sector remains a major pillar of Australia’s bilateral assistance to <strong>Fiji</strong>. AusAID’s<br />

current support to <strong>Fiji</strong> is given through the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> Improvement Program (FHSIP)<br />

and support for the <strong>Fiji</strong> School of Medicine (FSMed). In addition, AusAID currently provides<br />

support through a number of NGOs and a range of major regional programs in areas of<br />

HIV/AIDS; non-communicable diseases, support for equipment maintenance and biomedical<br />

engineering, visiting medical specialists and pandemic influenza preparedness.<br />

AusAID now wishes to build on the work of these programs and to move ahead with<br />

planning for a new program of support upon completion of the FHSIP. In order to make<br />

decisions on its future programs, AusAID now seeks to obtain good baseline data and<br />

analysis of the health sector situation, including progress towards achievement of the health<br />

related MDGs 4, 5, and 6.<br />

It has therefore commissioned this current situational analysis (the assessment) which will<br />

inform scoping and design of a future assistance program in health for <strong>Fiji</strong> sometime in mid-<br />

2009. The Objectives of this assessment are<br />

1. To provide a ‘snapshot’ of the current status of the health sector in <strong>Fiji</strong> from health<br />

service delivery and systems levels;<br />

2. To present and assess the state of health based on latest data and statistics, determine<br />

limitations of data and propose methodologies to enable tracking for MDGs and any<br />

future program support indicators;<br />

3. To identify opportunities and gaps for future AusAID programming, including<br />

strategic objectives and likely areas of impact.<br />

The assessment team visited <strong>Fiji</strong> from 29 th October to 18 th November. It visited health sector<br />

facilities and met with a wide range of government officials, international agencies, other<br />

development partners, training institutions and NGOs. The results of this “snapshot” mission<br />

and the issues that arose from it are presented in the report and summarised here.<br />

The Economic and Political Situation<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> is an island nation in the south-west pacific, with an ethnically diverse population of<br />

837,271 people of whom approximately 56% are ethnic <strong>Fiji</strong>ans, 37% indo-<strong>Fiji</strong>an and the<br />

remainder consisting of other ethnic groups including Caucasian and Chinese. Its main source<br />

of revenue is from tourism, sugar, mining and agriculture. National GDP at constant price<br />

was $3.505 billion in 2000 and this has grown to $5.826 billion in 2007. The country has a<br />

relatively good infrastructure to support its development and the populations’ standard of<br />

living is declining. It is rated by UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) as being one of the<br />

medium developed countries being ranked 92 nd among a listing of 177 nations in 2006.<br />

However this represents a decline from position 46 in 1995.<br />

Despite its middle ranking status and the important role that <strong>Fiji</strong> enjoys as a regional centre,<br />

its development has been curtailed over the past 2 decades by political instability. The<br />

country has not yet attained the levels of development that were predicted for it in the early<br />

1980s. There has been widespread migration to Australia, New Zealand, the USA and more<br />

recently selective migration to the Middle East. This is particularly apparent among the<br />

educated and professional groups which <strong>Fiji</strong> can ill afford to lose. Doctors and nurses have<br />

migrated in large numbers, as shown in this report. This outward migration is having a very<br />

negative effect on the staffing of the MoH.<br />

The <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> in <strong>Fiji</strong><br />

vi

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

The MoH is by far the largest provider in the health sector although there is a growing private<br />

sector and a large number of NGOs some of whom now provide services to the public. Basic<br />

health care is provided to all residents through a hierarchy of village health workers, nursing<br />

stations, health centres, sub-divisional hospitals and divisional and specialized hospitals. This<br />

framework was put in place to provide ready access to all and has been functioning for many<br />

years.<br />

As stated above, this model has served the country well, but over recent years issues such as<br />

demographic and social change, improved transport and changing medical standards have<br />

meant that, while the framework is still very relevant today, the location and size of the<br />

building blocks requires review. Evidence seen at first hand during this mission indicates that<br />

some centres are overstaffed, while some are considerably understaffed. This has resulted in<br />

long waiting times at the general outpatient departments of divisional hospitals and some<br />

larger health centres. Equally important is the fact that many people are now bypassing<br />

nursing stations and health centres to go directly to divisional hospitals or other centres that<br />

are more convenient to them e.g. on a bus route or easy-access road. As a result the role of<br />

some centres may need to be re-assessed.<br />

Staffing the <strong>Health</strong> Service<br />

Within <strong>Fiji</strong>, this assessment mission found that workforce issues are of major concern to both<br />

curative and public health departments of the Ministry – although clinical areas are most<br />

acutely affected. In particular a shortage of key cadres of staff was reported to the team as<br />

being perhaps the single major issue facing the MoH – and it may worsen with the current<br />

directive by the PSC to reduce the workforce of the public sector by 10% .<br />

While there are adequate numbers of junior medical staff to fill the established positions<br />

(some would argue that these establishment levels have remained unadjusted for years despite<br />

workload increases), this assessment shows that, for all 4 levels of senior medical officers,<br />

including specialists, there is a serious shortage, with 36% of established positions being<br />

vacant.<br />

The continued shortage of specialist medical officers will, over time lead to a serious<br />

deterioration of service levels. At the divisional hospitals, waiting times for surgery are<br />

getting increasingly longer and the shortage of obstetricians and paediatricians is impacting<br />

on the care of mothers and babies. Furthermore, because of the lack of specialist medical<br />

officers and specialist nurses, the sub-divisional hospitals are functioning as little more than<br />

large health centres. Surgery, including caesarean sections, and other specialist medical<br />

services are no longer available at sub-divisional hospitals even though the hospitals may still<br />

have a functioning operating theatre and have provided these services to their communities in<br />

the past.<br />

There are shortages in other specialist areas. While there is now no shortage of generally<br />

trained nurses (there may in fact be a surplus within 2-3 years), there is a shortage of some<br />

cadres of specialist nurses, including those with specialist skills in intensive care and accident<br />

and emergency. Other areas of concern include biomedical engineering and IT support and<br />

specialist programmers.<br />

Funding the health service<br />

Financial constraints remain an ongoing problem facing the MoH. The figures presented in<br />

the report indicate that although there has been an increase in the size of health budget in<br />

recent years, the per capita health expenditure has declined from $176 in 2005 to $ 163 in<br />

<strong>2008</strong>. The MoH budget as a percentage of GDP was 2.57 in <strong>2008</strong>, representing a continuing<br />

vii

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

and steady decline from over 4 percent in 1993. It remains the lowest percentage of GDP of<br />

all countries in the <strong>Pacific</strong>.<br />

While there is some level of cost recovery, charges are very low and the amount of revenue<br />

raised is negligible. Clearly public debate is needed to establish acceptable principles of<br />

revenue collection in the context of the political and economic state of the nation. Equally<br />

important there is a need for public debate on the erosion of public health financing in <strong>Fiji</strong>,<br />

with a view to generating commitment from successive governments to incrementally<br />

increase the share of GDP allocated to health to at least that of its <strong>Pacific</strong> neighbours.<br />

There is some level of private health insurance but this is limited to those in the workforce<br />

and provides access to Suva Private Hospital and, in most cases, covers offshore referral for<br />

medical emergency.<br />

The <strong>Health</strong> of the People of <strong>Fiji</strong><br />

Key health indicators are presented in the report. <strong>Fiji</strong> made considerable progress in<br />

improving its key health indicators up to 1990, when they were seen to be excellent. During<br />

that period, life expectancy, and both maternal and infant mortality improved significantly,<br />

with MMR improving from 156.5 (per 100,000 live births) in 1970 to 53.0 in 1980 and 26.8<br />

in 1990.<br />

However since the mid 1990s, progress has stalled or deteriorated. Infant mortality rates were<br />

16.8 in 1990 but had worsened to 18.4 in 2007. Maternal mortality rates of 26.8 in 1990 had<br />

worsened to 31.1 in 2007. Both were well short of the MDGs of 5.6 for infant mortality and<br />

10.3 for maternal mortality. Clearly the MOH is not meeting these targets and data present in<br />

the full report show that under 5 mortality, infant mortality and maternal mortality are not<br />

only worse than the commitment given in the MDGs in 2000, but are considerably worse than<br />

the status in 1990.<br />

Particularly disturbing was a dramatic rises in the incidence of congenital syphilis to levels of<br />

162 cases in 5,635 lives births at the CWM hospital for the first 9 months of <strong>2008</strong>. This also<br />

serves as an endpoint indicator of an antenatal care system that needs more support.<br />

Major causes of morbidity include infection and parasitic disease (including Dengue, TB and<br />

HIV), NCD, diseases of the circulatory system; accidents and injury and diseases of the<br />

respiratory system. Major causes of mortality include diabetes and other NCDs,diseases of<br />

the circulatory system, infection and parasitic diseases, neoplasms and diseases of the<br />

respiratory system.<br />

Issues affecting the health service arising from this assessment.<br />

Apart from financial constraints and staff shortages - especially of senior level medical<br />

officers - eight other important areas were identified. These include:<br />

1. A general poor perception of the health services by the public<br />

2. Changes in demographics and social behaviour require a rethink of the location,<br />

staffing and range of services provided by health facilities.<br />

3. Relatively poor progress towards the achievement of <strong>Fiji</strong>s MDGs.<br />

4. Old or non-functioning equipment impacts on service delivery<br />

5. Stock outs of essential drugs are still occurring despite some progress over the past 12<br />

months<br />

6. There is a need for more focused planning and better use of management information<br />

systems – there appears to be a significant disconnect between the MoHs corporate<br />

plans and achievement of its KPIs<br />

viii

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

7. The health sector should be seen as being more than just the MoH – MoH should<br />

consider working more closely with its partners including the private sector, NGOs<br />

and the international agencies.<br />

8. There is a need for stronger evidence based approach to policy and planning and this<br />

will require a dedicated program or operational research<br />

Possible areas for future AusAID support.<br />

Eight possible areas of support are listed. However it is not recommended that AusAID try to<br />

address more than 3 of these areas - 1 or 2 would be preferable. In a review of the progress<br />

being made by the FHSIP that was carried out concurrently with this <strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong>, it<br />

was concluded that despite a number of important achievements no truly visible impact can<br />

be seen as judged by measureable progress towards the achievement of the MOHs own KPIs.<br />

In large measure this reflects the fact that the program’s activities are spread very widely,<br />

with little focus on a core set of activities.<br />

It is recommended that initial priority should be given by AusAID to assisting the MoH to<br />

achieve its MDG 4 (infant and child mortality) and MDG 5 (maternal mortality) targets.<br />

Although no design is included, the outline of a suggested approach to supporting this<br />

initiative is given in the full text.<br />

The eight areas identified for support by AusAID or other development partners are:<br />

i. Provide targeted support to the MoH to reduce its level of infant mortality (MDG 4)<br />

and maternal mortality (MDG 5).<br />

ii.<br />

iii.<br />

iv.<br />

provide support to address a limited number of the other national KPIs. These KPIs<br />

might include reduced amputation rates for diabetic sepsis (from 13% to 9%) ,<br />

elimination of drug “stock-outs “ or reduction in teenage pregnancy rates (from 16%<br />

to 8%). Obviously the choice of which of the national KPIs (listed in Annex 11)<br />

would be a matter for the Ministry.<br />

Support to review the “framework” currently in place to ensure access to health<br />

services. This should take account of changes over the last 30 years. Such a review<br />

should ask the question “what do we want the health sector to look like in 2020” and<br />

begin planning for it now.<br />

Support a culture of evidence based policy. This would be done by providing support<br />

for key operational research projects aimed at making the sector more efficient and<br />

effective.<br />

v. A program of continued capacity development in key areas. This would include<br />

management and supervision; planning, monitoring and evaluation. The Project<br />

Officer and Performance Enhancing Projects “models” introduced through the FHSIP<br />

should be continued.<br />

vi.<br />

vii.<br />

There is a need to continue to upgrade PATIS and other <strong>Health</strong> Information Systems<br />

(including training). FHSIP will continue to provide some support in this area during<br />

2009. However it is recommended that further AusAID support beyond the end of<br />

FHSIP should not be continued until there is some indication as to whether the IGOF<br />

will provide the necessary ongoing financial and specialist staffing support to enable<br />

this to be sustainable.<br />

Continued support for NGOs, who need to scale up and widen their activities.<br />

Continued donor support will enable them to do this and to play a more positive role<br />

as “partners” of the MoH.<br />

ix

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

viii.<br />

Continued support for Regional Programs, especially in the area of disease control.<br />

What is proposed here is not a new program in this area but rather that the current<br />

regional disease control activities being supported by AusAID, and especially support<br />

for NCDs and diabetes prevention and control, should be continued and even<br />

strengthened. There should be an attempt when designing regional programs to ensure<br />

that activities fit within national plans and that there is greater ownership and<br />

understanding of the programs at the senior level within individual countries.<br />

Although shortages of senior cadres of staff, and especially specialist medical officers, is<br />

identified as a major issue impacting on the quality of health care in <strong>Fiji</strong>, no specific program<br />

of AusAID support is recommended here. However FSMed will need to increase its postgraduate<br />

output to begin to address this issue, recognising that the decision on the allocation<br />

of scholarships ultimately resides with IGOF. In addition the suggested programme of<br />

targeted support to address the MDG, by the very broad nature of the suggested approach,<br />

may address staffing issues in relevant areas.<br />

A list of recommendations made throughout the report follow.<br />

x

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

Recommendations<br />

Recommendation 1<br />

Continued efforts need to be made to increase the number of medical post-graduates from the<br />

FSMed. With this in mind, the IGOF should continue to allocate priority for postgraduate<br />

medical training when it allocates scholarships, either those that are internally funded or<br />

funded by its development partners.<br />

Recommendation 2<br />

The MoH should continue to work with the PSC to improve the salaries, allowances and<br />

incentives offered to specialist medical officers and specialist nurses with a view to reducing<br />

the level of outward migration and retaining their services within the <strong>Fiji</strong> health sector.<br />

Recommendation 3<br />

The MoH should consider undertaking regular surveys at the major hospitals (and other<br />

centres) to determine waiting times for patients attending at different times of the day and on<br />

different days. Concurrently, independent patient satisfaction surveys could be carried out to<br />

explore other issues such as staff attitude and drug outages. The results from such surveys<br />

could guide the implementation of a Service Improvement Program. The FHSIP should be<br />

asked to include funding for such surveys within its workplan for 2009.<br />

Recommendation 4<br />

The MoH should consider undertaking a review of the location, functions, staffing levels and<br />

operating hours of the current network of nursing stations, health centres, subdivisional and<br />

divisional hospitals to ensure that they better serve the needs of the people of <strong>Fiji</strong>. It is<br />

recognised that external assistance may be required for such a Review and development<br />

partners should look favourably on providing such support as it will offer the potential to<br />

significantly improve the efficiency of service delivery.<br />

The Clinical Services Planning Framework, developed with support of the FHSIP, should be<br />

a key tool in this exercise.<br />

Recommendation 5<br />

A carefully planned study should be undertaken of antenatal care practices in <strong>Fiji</strong>, which<br />

should include women in both urban and rural areas.<br />

Recommendation 6<br />

The MoH and its partners should consider developing “action” plans that focus specifically<br />

on reducing the levels of infant and maternal mortality. Such plans should cut across all<br />

departments of the MoH and engage with all relevant parties both within and outside of the<br />

Ministry.<br />

Recommendation: 7<br />

All options should be explored on ways to increase the level of funding made available<br />

through the national budget, and through development projects for the standardisation and<br />

procurement of essential biomedical equipment.<br />

Similarly, options should be explored on ways to increase the level of funding available for<br />

maintenance and repairs of biomedical equipment and to simplify the processes for the<br />

procurement of replacement spare parts and consumables.<br />

xi

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

Recommendation 8.<br />

Recognising the very critical state of biomedical equipment procurement and repair,<br />

development partners might consider a large scale biomedical equipment project that seeks to<br />

purchase standardised equipment for the divisional hospitals in order to bring equipment up<br />

to acceptable levels. Any such project should also review the processes required for the<br />

maintenance of equipment and purchase of spare parts. Such a project should work with but<br />

be outside of the current support that AusAID is giving to strengthening biomedical<br />

engineering departments within the region.<br />

Recommendation 9<br />

Although access to essential drugs at the health facility level is improving and “stock outs”<br />

are occurring less frequently, more needs to be done, especially in the Northern Division.<br />

Any steps to improve the efficiency of drug supply should include a formal audit of the<br />

central pharmacy store , its processes and an assessment of the technical capacity of the staff<br />

to ensure that their skills match the needs of the job. FHSIP should be able to continue its<br />

support in this area during 2009, and include such an audit in its workplan<br />

Recommendation 10.<br />

The MOH should take the lead in recognising that the “health sector” consists of other<br />

partners besides the MOH.<br />

Working with outside support if necessary, it should explore ways in which it can work with<br />

these other parties, including private medical practitioners, to put in place more functional<br />

operational partnerships that better define the role of the respective partners in supporting the<br />

MOH to achieve the overall goals of the sector.<br />

It should also seek to obtain meaningful information on the range and volume of health<br />

services performed by these other parties.<br />

Recommendation 11.<br />

It is recommended that initial priority for any AusAID support beyond 2009, should be given<br />

to assisting the MoH to achieve its own MDG 4 (infant and child mortality) and MDG 5<br />

(maternal mortality) targets.<br />

Many of the issues raised in this set of recommendations are already known to the MoH.<br />

Indeed many of the recommendations take account of views expressed to the team by senior<br />

officials. However the recommendations themselves have not been discussed specifically<br />

with the Permanent Secretary and his Executive.<br />

xii

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

THE CURRENT SITUATION<br />

1. INTRODUCTION<br />

1.1. Background<br />

Australia remains committed to support <strong>Fiji</strong> to strengthen its health services. This reflects<br />

continuing support over the past decade including: community development projects in<br />

Kadavu and Taveuni (including the construction of new sub-divisional hospitals);<br />

strengthening the capacity of the National Centre for <strong>Health</strong> Promotion, support to the<br />

FSMed to introduce postgraduate medical training and more recently to strengthen the overall<br />

capacity of the School. AusAID has also sought to strengthen the capacity of the MoH to<br />

effectively manage its services and has provided support through the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Management<br />

Reform Project (FHMRP) for management training, the introduction of the PATIS health<br />

information system (phase 1) and importantly to support the MoH plan for the<br />

decentralisation of health services.<br />

AusAID is currently providing ongoing support for the FSMed and the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong><br />

Improvement Program (FHSIP), which supports the MoH to implement its own corporate<br />

plans across a broad range of public health, curative services and administrative services.<br />

In addition, AusAID has provided support to <strong>Fiji</strong> through multilateral programs, support for a<br />

number of NGOs and a range of major regional programs in the area of HIV/AIDS, noncommunicable<br />

diseases, support for equipment maintenance and biomedical engineering,<br />

visiting medical specialists and pandemic influenza preparedness.<br />

The sector remains a major pillar of Australia’s bilateral assistance to <strong>Fiji</strong> and AusAID now<br />

wishes to move ahead with planning for a new program of support upon completion of the<br />

FHSIP project. To make decisions on its future programs, AusAID now seeks to obtain good<br />

baseline data and analysis of the health sector and of the issues that it faces in the future that<br />

may impact on the effective delivery of services. This includes the achievement of the sectors<br />

goals, including progress towards achievement of the health related MDGs 4, 5, and 6.<br />

It has therefore commissioned this <strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> (the assessment), which will inform<br />

scoping and design of a future assistance program in health for <strong>Fiji</strong> sometime in mid-2009.<br />

1.2. Objectives and Methodology used for this <strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong><br />

The objectives for the assessment included in the TORs for the mission (see Annex 1) are as<br />

follows<br />

1. To provide a ‘snapshot’ of the current status of the health sector in <strong>Fiji</strong> from health<br />

service delivery and systems levels;<br />

2. To present and assess the state of health based on latest data and statistics, determine<br />

limitations of data and propose methodologies to enable tracking for MDGs and any<br />

future program support indicators;<br />

3. To identify opportunities and gaps for future AusAID programming, including<br />

strategic objectives and likely areas of impact. This assessment should be based on an<br />

assessment of the <strong>Fiji</strong> National <strong>Health</strong> Strategy and AusAID’s health sector programs<br />

in <strong>Fiji</strong>, including FHSIP, other bilateral, regional and donor partners’ programs.<br />

The Assessment was carried out in <strong>Fiji</strong> from 29 th October to 18 th November <strong>2008</strong> by a health<br />

development effectiveness specialist and team leader (Dr Ross Sutton); a health specialist (Dr<br />

Graham Roberts of FSMed) and a health data analyst (Mr Dharam Lingam – also of FSMed).<br />

The FSMed team members had recently commenced work on health financing and had a<br />

1

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

good level of local knowledge of the <strong>Fiji</strong> health system. Unfortunately, Dr Roberts joined the<br />

team late due to unforeseen family circumstances and could not participate in meetings<br />

during the first 5 days of the assignment.<br />

The team visited health facilities in the Central, Western and Northern Divisions. While in<br />

Suva the team met with AusAID and with officials from the MoH; CWM hospital, PSC,<br />

Ministry of Finance and National Planning (MF&NP), Consumer Council of <strong>Fiji</strong>, the FHSIP<br />

program, Attorney Generals Department, WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, JICA and the EU. The<br />

team also met with a range of NGOs and community bodies including the <strong>Fiji</strong> College on<br />

General Practitioners (representing doctors in private practice). While in the Western and<br />

Northern Divisions the team visited a range of health facilities (nursing stations, health<br />

centres, subdivisional hospitals and divisional hospitals) and met medical and nursing staff in<br />

each facility. They also met with senior managers and their staff from the Community <strong>Health</strong><br />

and Management Services areas. The team also met with managers and staff from PC&SS<br />

(an NGO providing counselling services) in Nadi. The list of Key Persons Met is in Annex 2.<br />

Data was collected using material available in the MoH’s annual reports and department of<br />

statistics, the <strong>Fiji</strong> Islands Bureau of Statistics, MoF&NP finance circulars and <strong>Fiji</strong> Budget<br />

Estimates, PSC, Land Transport Authority and from sources contacted during this mission.<br />

The analysis sought to provide a “snapshot” of the health sector and is not considered to be a<br />

full review. As such, the actual time allocated for the assessment was relatively short. In<br />

addition the team leader also undertook a “progress check” of the current FHSIP<br />

concurrently with the assessment mission. That report is not included here.<br />

2. THE FIJI SETTING<br />

2.1. <strong>Fiji</strong> - Demographic and Country overview.<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> is a small island state at the hub of the south-west <strong>Pacific</strong> midway between Vanuatu and<br />

the Kingdom of Tonga. The population (2007) was 837,271 comprising 475,739 ethnic<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong>ans, 313,789 Indo-<strong>Fiji</strong>ans and 47,734 of other ethnic groups. Overall, the rural population<br />

was 412, 435 and the urban 424, 846. The average annual growth rate is 0.8% (the natural<br />

increase of 1.2% minus migration) with crude growth rates being higher in the <strong>Fiji</strong>an than in<br />

the Indo-<strong>Fiji</strong>an population. Areas with noticeably increased population over the past few<br />

years are the Western Division (55,266) and Central Division, where the population of the<br />

Suva and Nausori urban and peri-urban areas has increased by 32,300. <strong>Fiji</strong>’s population by<br />

age and ethnicity is shown in table 1. Thirty nine percent of the population is less than 20.<br />

Table 1. 2004-5 survey of population by age and ethnicity<br />

Age Group <strong>Fiji</strong>an Indo-<strong>Fiji</strong>an Others Rotuman All % by Age<br />

0-4 46,068 20,519 2,567 980 70,134 8.6%<br />

5-19 143,362 96,342 8,443 3,351 251,498 30.7%<br />

20-49 184,347 170,582 13,299 4,315 372,543 45.5%<br />

50-64 40,078 44,206 3,497 1,449 89,230 10.9%<br />

65+ 17,898 14,582 1,461 607 34,548 4.2%<br />

Total 431,753 346,231 29,267 10,702 817,953 100%<br />

% by ethn’y 52.8% 42.3% 3.6% 1.3% 100%<br />

Source: 2004-05 Employment and Unemployment Survey<br />

2

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

<strong>Fiji</strong>’s Economic Exclusive Zone contains 332 islands covering a total land area of 18,333 sq<br />

km in 1.3 million sq km of the South <strong>Pacific</strong>. It is a multi-cultural and multi-religious country<br />

where different cultures meet and to some extent merge. Literacy rate is around 94%, with<br />

English being the official language and <strong>Fiji</strong>an and Hindi the languages of daily use. The 2007<br />

census indicated that 51% of the population is now urban with urban growth rate being 1.7%<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong>’s housing and employment crises are pervasive and will be compounded over time by<br />

high rates of school drop-out. As land leases expire and food costs rise, squatter settlements<br />

now number 200 with an estimated population of 100,000 people. Sixty eight percent of the<br />

workforce earns less than $7,000 per year. See Annex 3 for further information on income<br />

among different ethnic groups within <strong>Fiji</strong>.<br />

2.2. Economic and Political Situation.<br />

Main sources of revenue are tourism, sugar, mining, agriculture and bottled water. National<br />

GDP at constant price was $3.505 billion in 2000 and had grown to $5.826 billion in 2007.<br />

The country has a relatively good infrastructure to support its development but the overall<br />

standard of living is declining. It is rated on the UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) as<br />

being one of the medium developed countries, being ranked 92 nd among a listing of 177<br />

nations in 2006. However this represents a decline from position 46 in 1995. There is<br />

poverty, as reflected by the drop in ranking on the HDI, but it is not overtly apparent as seen<br />

in Africa, and some other Melanesian countries. However, poverty is increasingly becoming<br />

an issue that the present and future governments must deal with. Generally there is an<br />

adequate food supply for all although this should not imply that all have a well-balanced diet<br />

as indicated by the increasing incidence of NCDs.<br />

Despite its middle ranking status and the important role that <strong>Fiji</strong> enjoys as a regional centre,<br />

its development has been curtailed over the past 2 decades by political instability. The<br />

country has not attained the levels of development that were predicted for it in the early<br />

1980s. A series of 4 coups over the past 20 years has been a potential catalyst for an increase<br />

in migration from <strong>Fiji</strong> to Australia, New Zealand, the USA and more recently more selective<br />

migration to the Middle East. This is particularly apparent among the educated and<br />

professional groups which <strong>Fiji</strong> can ill afford to lose. Doctors and nurses have migrated in<br />

large numbers, as shown in this report.<br />

Thus <strong>Fiji</strong>’s economy has been repeatedly stressed by political changes since 1987 and<br />

subsequent fluctuations in the levels of private investment, fuelled in part by migration and<br />

the removal of preferential subsidies for sugar sold to the European Union, to reduce further<br />

by 35% in 2009. Increasing prices of oil and food imports have stressed the economy further<br />

while the decline in sugar production and in garments exports contribute more directly to<br />

poverty. The economy has become increasingly dependent on tourism, remittances from<br />

overseas, gold and forestry exports.<br />

The current Interim Government has been in place since December 2006. They have<br />

identified certain conditions to be in place prior to <strong>Fiji</strong> proceeding to a general election.<br />

These include adoption of the People’s Charter, within which Pillar 10 addresses issues of the<br />

health sector and proposes to ‘increase the proportion of GDP allocated to health by 0.5%<br />

per annum for the next 10 years to achieve a level of 7% of GDP’. The achievement of this<br />

objective would result in significantly increased funding for the health sector, yet in the<br />

current global and national economic climate achieving the increase will require continued<br />

advocacy for health developments in the face of competing demands; and the MoH to<br />

demonstrate that it uses its resources effectively.<br />

In the Reserve Bank Press Release (No. 30/<strong>2008</strong> 28 th November) the Governor of the RBF<br />

announced that “the domestic economy remained weak with growth forecast at 1.2 percent<br />

3

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

for <strong>2008</strong>, a downward revision from the earlier forecast of 1.7 percent” and that “the balance<br />

of payments was still forecast to remain under pressure, underpinned by a wide trade deficit”.<br />

In October <strong>2008</strong> inflation was at 8.5% down from a 20 year high of 9.8% in September.<br />

3. ORGANISATION, STAFFING AND FUNDING OF THE HEALTH<br />

SYSTEM.<br />

3.1. Overview of the MoH, its structure and organisation<br />

The MoH is by far the largest player in the health sector. It provides health care services<br />

directly to citizens of <strong>Fiji</strong> and to a limited extent to tourists and persons referred from within<br />

the region. The MoH also serves a role monitoring compliance of outside bodies; issues<br />

permits, provides reports and regulates the functions of professional bodies. Basic health care<br />

is provided to all residents through a hierarchy of village health workers, nursing stations,<br />

health centres, sub divisional hospitals and divisional and specialized hospitals. This<br />

framework was put in place to provide access to all and has been functioning for many years.<br />

A more detailed discussion of this is given below at 3.2. The location of these health facilities<br />

is shown in maps at Annex 4.<br />

The Ministry underwent a process of reform commencing in 1999. Under the guidance of the<br />

GOF, and with support initially from the AusAID funded FHMRP, and later with support<br />

from the FHSIP, responsibility for much of the day-to-day operation of the health services<br />

was slowly devolved from the head office in Suva to restructured divisional offices in each of<br />

the divisions. While the head office was to retain responsibility for all policy, for national<br />

standards, for overall planning monitoring and evaluation of performance, the actual delivery<br />

of services would be the responsibility of the divisions. A feature of the divisional structure<br />

was the bringing together of public health and curative services under one Divisional Director<br />

of <strong>Health</strong> who would be in a better position to allocate resources across the two areas of<br />

health care within the divisions. This decentralisation process progressed steadily and after 5<br />

years was very widely accepted by the staff. This current assessment team heard many<br />

positive comments on the efficiency gains that were slowly being made through the process.<br />

However in <strong>2008</strong>, subsequent to IGOF concerns to more tightly control limited government<br />

resources, senior staff and management functions were re-centralised into the MoH head<br />

office in Suva under the process of “roll-back of reform”.<br />

The assessment team heard many strong views in support of the original decentralisation plan<br />

as Divisional staff were empowered to make local-level decisions that was helping them to<br />

make local improvements.<br />

Following the recentralisation a new organisation structure for the Ministry is being<br />

developed with agreement of the PSC. However this has not yet been finalised. It is thus not<br />

possible to include an official organisation chart in this report as one has not yet been agreed.<br />

However, the organisation charts for HQ and sub-divisional level were recently proposed to<br />

PSC – but have not yet been approved (they are shown at Annex 5).<br />

The situation was further complicated when, early in 2007, the MoH was combined with the<br />

Ministry of Women and Social Welfare.<br />

3.2. The Service Delivery Framework – a traditional model<br />

The model of service delivery – from nurse to health centre, to sub-divisional hospital, to<br />

divisional hospitals and ultimately to the CWM as the central referral hospital, has served <strong>Fiji</strong><br />

well. These different levels of the health system are defined in the Clinical Services Planning<br />

Framework (CSPF) as follows:<br />

4

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

Village/Community <strong>Health</strong> Service: Although not formally a MoH service, the<br />

Village/Community <strong>Health</strong> Service provides an important community link for MoH<br />

health services.<br />

Nursing Station Service: This is mainly a primary health care service, provided by a<br />

solo district nurse who is on call 24 hours a day. It caters for a catchment population<br />

range of approximately 200 to 5000. The average travelling time from a nursing<br />

station to the health centre by the most commonly used mode of transport is 1 hour 20<br />

minutes<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Centre Services: This facility provides Primary <strong>Health</strong> Care Services at a<br />

‘step-up’ from the nursing station as it is the first point of medical support for a<br />

number of nursing stations, which make up a medical area. The average travelling<br />

time from a health centre to a sub-divisional hospital by the most commonly used<br />

mode of transport is 2 hours 37 minutes<br />

Sub-divisional Hospital Service: General medical practitioners, midwives, registered<br />

nurses and assistants who work across inpatient, outpatient and community settings<br />

provide this service. This service operates on an on call service and is the first point of<br />

referral from health centre level. The average travelling time from sub-divisional<br />

hospital to divisional hospital by the most commonly used mode of transport is 4<br />

hours 20 minutes.<br />

Divisional Hospital Service: This service is provided by specialists, medical and<br />

nursing staff with a full range of diagnostic and allied health support services. The<br />

divisional hospital services also serve as a teaching institution for medical and nursing<br />

students. Divisional hospitals also coordinate visiting national and international subspecialist<br />

teams in Intensive Care, Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, Plastic Surgery<br />

(Interplast), Neurosurgery, Urology, Vascular Surgery and Paediatric Surgery, while<br />

some patients are referred for overseas medical treatment.<br />

Specialized Hospital Service: This provides only selected specialty services namely<br />

psychiatry, rehabilitation and chronic infectious disease services (TB & Leprosy).<br />

These services are based in Suva, and act as a national referral service.<br />

A more detailed description of the different levels of health facilities is at Annex 6<br />

and table 2 shows the distribution of these different levels of care by Division<br />

Table 3: Distribution of <strong>Health</strong> Facilities by Division Source CSPF 2005<br />

Institutions<br />

Divisions<br />

Central Western Northern Eastern<br />

Total<br />

Divisional Hospitals 1 1 1 - 3<br />

Specialised Hospitals 3 - - - 3<br />

Sub-divisional Hospitals 4 5 3 4 16<br />

Area Hospitals 1 - - 2 3<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Centres 21 24 19 14 78<br />

Nursing Stations 17 22 20 24 82<br />

Community Nursing Stn 5 3 1 7 17<br />

Old People’s Home 1 1 1 - 3<br />

As stated above, this model has served the country well, but over recent years demographic<br />

and social change, improved transport and changing medical standards have meant that, while<br />

the framework is still relevant today, the location and size of the building blocks requires<br />

review. Evidence to this effect was presented to the assessment team and as this issue is<br />

5

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

considered to be particularly important to the efficient operation of the health system in the<br />

future, it is discussed in more detail at section 3.3. and especially at 5.2.<br />

3.3. Staffing the <strong>Health</strong> System<br />

3.3.1. Overview<br />

This continues to be a major issue in <strong>Fiji</strong> and indeed throughout the <strong>Pacific</strong>. The serious<br />

nature of workforce issues, and especially the shortage of key staff such as specialist medical<br />

officers, is reflected in the recent creation of the <strong>Pacific</strong> Human Resources for <strong>Health</strong><br />

Alliance. The Alliance is a network of representatives from individual pacific island countries<br />

supported by regional training institutions and “interested parties” from universities and<br />

professional bodies in Australia and New Zealand. It aims to address continuing problems<br />

relating to human resource development in the <strong>Pacific</strong>. WHO currently provides the<br />

secretariat for the Alliance.<br />

Within <strong>Fiji</strong>, this assessment mission found that workforce issues are of major concern to both<br />

curative and public health departments of the Ministry– although clinical areas are most<br />

acutely affected. In particular a shortage of key cadres of staff was reported to the team as<br />

being perhaps the single major issue facing the MoH – and it may worsen with the current<br />

request to reduce the size of the public sector workforce by 10% . These Issues of the<br />

adequacy of staff establishments and the difficulties to respond to emerging needs, graduate<br />

numbers in all health cadres, emigration of health personnel, remuneration, job evaluation,<br />

performance appraisal and career progression have been discussed and disputed in the <strong>Fiji</strong><br />

health system for many years but without a concerted and coordinated response.<br />

Unfortunately outward migration appears to have been accepted as an unavoidable<br />

phenomenon, resulting in the need to train more staff to fill vacant positions. However, the<br />

provision of newly trained staff to replace experienced staff is not an adequate response.<br />

Senior staff are leaving and are being replaced by less senior level staff, thus potentially<br />

putting at risk the overall quality of the workforce. Unfortunately in the current economic<br />

climate, the potential to increase staff establishments is unlikely, although within-budget<br />

changes to the mix of staff should be possible. This will be important to establish as it will be<br />

an unavoidable outcome of the review of the current service delivery framework referred to<br />

above at 3.2 and discussed in more detail at section 5.2.<br />

3.3.2. Service Delivery Staff<br />

Table 3 shows the number of doctors and nurses employed in each division.<br />

Table 3: Doctor and Nurse to Population Ratio by Division 2004<br />

Doctors<br />

Approved Popl’n Ratio<br />

Nurses<br />

Approved Popl’n Ratio<br />

Positions<br />

Positions<br />

Central/Eastern 159 1: 2704 890 1: 439<br />

Western 121 1: 3035 539 1: 516<br />

Northern 58 1: 3104 273 1: 586<br />

NATIONAL 338 1: 2896 1702 1: 532<br />

Note: These figures include only clinical posts and not senior administrators.<br />

Medical Staff<br />

Table 5 lists total medical staff engaged within the MoH. While there are adequate numbers<br />

of more junior medical staff to fill the established positions (some would argue that these<br />

establishment levels have remained unadjusted for years despite workload increases), the<br />

table shows that for all 4 levels of senior medical officers, including specialists, there is a<br />

6

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

serious shortage, with 36% of established positions being vacant. Clearly this has major<br />

implications for the delivery and quality of health services and for the supervision of medical<br />

students and interns within the public health system.<br />

Table 4. MoH Medical Cadre as at 31/10/08<br />

Post Grade Approved<br />

Establishment<br />

7<br />

Filled<br />

Vacant<br />

Consultant Specialist MD01 35 22 13<br />

Chief Medical Officer MD02 25 18 7<br />

Principal Medical Officer MD03 44 32 12<br />

Senior Medical Officer MD04 79 46 33<br />

Medical Officer MD05 168 170 +2<br />

Medical Intern MD06 35 49 +14<br />

Medical Assistant MD07 10 10 Nil<br />

Total 396 347 49<br />

Note: the surplus in ‘filled’ intern positions is of M.O.s held against those post.<br />

Shortage of Specialists and Senior level medical staff.<br />

The continued shortage of specialist medical officers will, over time lead to a serious<br />

deterioration of service levels. At the divisional hospitals, waiting times for surgery are<br />

getting increasingly longer (although an intense campaign of extended work-hours is<br />

currently seeking to address this); and the shortage of obstetricians, gynaecologists and<br />

paediatricians is impacting on the care of mothers and babies.<br />

This shortage of specialists has been felt for some years. For example, because of the lack of<br />

specialist medical officers and specialist nurses, the subdivisional hospitals have been<br />

restricted in the range of services they provide. The assessment team was continually told that<br />

surgery, including caesarean sections, and other specialist medical services are no longer<br />

available at subdivisional hospital even though the hospitals may still have a functioning<br />

operating theatre and have provided these services to their communities in the past. As<br />

examples, the subdivisional hospitals at Kadavu and Taveuni, constructed during the past 10<br />

years with AusAID support, have fully fitted-out operating theatres but do no surgery due to a<br />

lack of qualified surgeons.<br />

One factor associated with this shortage of specialists is the constraints on the FSMed to train<br />

enough medical officers – some of whom will go on to become specialists. A second reason<br />

for the shortage is the “pull” from countries both inside and outside the region who are<br />

offering much higher salaries but also, importantly, offer more attractive working<br />

environments. A third is what many have called the “push” being placed on doctors because<br />

of the stress they experience each day because of high workloads and poor working<br />

environments (lack of equipment, drugs etc). Together factors 2 and 3 result in a large level<br />

of outward migration as discussed at 3.3.3.<br />

General medical officers and private medical practitioners.<br />

Table 4 indicates that, compared with the establishment, there is no shortage of medical<br />

officers. Indeed there may be a slight surplus. However this may need to be interpreted with<br />

some caution as many of these positions are currently filled by foreign doctors from India,<br />

Philippines, Bangladesh, Burma, Nigeria, Pakistan and China on contract with the MoH.<br />

(Previously, in the 1980s <strong>Fiji</strong> sourced its overseas trained medical officers from Australia,<br />

UK and New Zealand). The cost of engaging these contracted doctors is higher than for<br />

equivalent local doctors and it is government policy to ultimately replace these doctors with<br />

locals.

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

When reviewing the medical workforce of <strong>Fiji</strong>, it needs to also be taken into account that<br />

there are currently approximately 120 medical officers in private practice (25% of the total<br />

medical workforce). In the main these are general practitioners; few are specialists and thus<br />

they will not help address the problem raised above. However, these general practitioners are<br />

providing a wide range of consultations, including antenatal care and childhood vaccinations.<br />

They are part of the health sector although the work they do is not included in the country’s<br />

overall health sector statistics. PSC mechanisms do exist to engage these doctors on a part<br />

time or locum basis within health centres and hospitals should this be needed in selected<br />

situations. These mechanisms have been tried on a small scale and there have been some<br />

problems but equally there have been some successes. However until this matter has been<br />

more fully explored, the role and use of private general practitioners in the public sector<br />

cannot be said to have been fully addressed. Using them more effectively will give the MoH<br />

greater flexibility in regard to medical officer staffing.<br />

In other steps to help relieve the shortage of medical officers: the FSMed has increased its<br />

intake of medical students from 70 to 80, of which 70 will be from <strong>Fiji</strong>. Another new medical<br />

school (under the University of <strong>Fiji</strong>) has just commenced in Lautoka, although its viability is<br />

still to be proven, and fifteen <strong>Fiji</strong>an medical students have been selected to undertake training<br />

in Cuba where their tuition will be in Spanish. It will be another 5-6 years before a judgement<br />

can be made on the registration and value to the <strong>Fiji</strong> health system of the Cuban graduates.<br />

Nurses, allied health and paramedical staff<br />

A similar phenomenon exists in the nursing cadre, with vacancies in higher levels but<br />

surpluses (against establishment) in lower level positions. Whether the MoH actually needs<br />

more nurses will be better established by the review proposed at recommendation 4. Because<br />

of the current establishment levels, the MoH now has difficulty in employing the number of<br />

new nurses that graduate annually. Last year the graduates of the Sangam School of Nursing<br />

in Labasa were not absorbed – and it appears that some graduates from the <strong>Fiji</strong> School of<br />

Nursing (FSN) will not be absorbed in 2009.<br />

Tables listing nursing, allied health and paramedical staff are given in Annex 6<br />

While there is now no shortage of generally trained nurses at the staff nurse level, there is a<br />

shortage of some cadres of senior level nurses and importantly of specialist nurses including<br />

those with specialist skills in intensive care and accident and emergency. Nurses trained in<br />

these areas are in demand from the more developed countries. Many nurses are migrating to<br />

Australia, New Zealand and to Dubai and other destinations in the Middle East (see 3.3.3.)<br />

where high salaries are on offer. It is understood that a considerable amount of the resignation<br />

and outward migration of nurses shown in Table 8 below relates to these specialist nurses.<br />

The team was informed that in part this represents the attraction of higher salaries and<br />

working conditions but in part it is a reflection of the fact that promotion for nurses in <strong>Fiji</strong> is<br />

usually based on seniority and not necessarily on merit or special skills. As a result these<br />

specialist nurses, who in many cases have graduated in the last ten years, find that, despite<br />

their specialist skills, to get promotion they must move outside of their specialty or go<br />

overseas.<br />

Annex 6 shows that there is generally no shortage of established paramedical and allied<br />

health cadres in <strong>Fiji</strong>. Important however is the fact that there are no posts for cadres that are<br />

considered essential in many countries’ health systems – psychologist, counsellors, social<br />

workers, occupational health workers, podiatrists among others. As discussed elsewhere in<br />

this report counselling services within <strong>Fiji</strong> are now being provided by the NGO <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

Counselling and Social Services (PICASS).<br />

Other Cadres of staff.<br />

8

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

There are two other staffing areas of concern, which are in biomedical engineering and IT.<br />

The MoH has had perennial difficulty in maintaining its biomedical equipment. AusAID<br />

support has previously been provided in this area but the problems remain as discussed in<br />

section 5.4. of this report. At the root of this problem is the ongoing difficulty of recruiting<br />

biomedical engineers. There is need both to increase the establishment in this area and have<br />

biomedical engineers in each of the three main hospitals and also create attractive salary and<br />

conditions to hold such people who otherwise will be attracted to other areas such as<br />

telecommunications, and airline equipment maintenance. The costs in external maintenance,<br />

transport of equipment needing repair, downtime of equipment and importantly in<br />

deterioration of patient care because of poor equipment, far exceeds the cost of employing<br />

specialist staff. See section 5.4 for further discussion on the poor state of equipment within<br />

the health sector.<br />

Similarly there is an acute shortage of IT specialists and the level of computer literacy is<br />

often low. Although FHSIP provides funding to support a full-time IT Specialist for MoH,<br />

the need for IT staff to maintain, extend and fully utilise PATIS was apparent to the team.<br />

The limited application of PATIS may undermine its success, while those who use it find it<br />

can provide valuable information. It is apparent that the additional workload placed on nurses<br />

to enter data into PATIS is a barrier to its success, and it would be wise for MoH to allocate<br />

resources and develop people and procedures to improve data entry and the use of PATIS as a<br />

management tool (see also 5.6).<br />

3.3.3. The Problem of Resignation and Outward Migration from the MoH<br />

The importance of resignation and outward migration has already been discussed. Table 5<br />

shows the ‘exits’ of staff from the public health care system between 2003 to 2007, through<br />

resignation, retirement, death or expiry of contract, revealing a high turnover in all cadres .<br />

In these five years the equivalent of 40% of the medical and 33% of the nursing approved<br />

establishments exited the public health system.<br />

Table 5: ‘Exit’ of staff from MoH over 5 years (2003-7)<br />

Cadre 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Total Av.p.a.<br />

Medical Officers 29 40 37 31 23 160 32<br />

Nurses 25 64 162 216 78 545 109<br />

Paramedical 15 15 19 19 13 81 16<br />

Dental 4 4 13 10 5 36 7<br />

Pharmacy 4 3 18 8 8 41 8<br />

Total 77 126 249 284 127 863 173<br />

This issue of resignation and outward migration of senior medical and nursing staff has been<br />

discussed earlier and remains a major problem for the Ministry and for the PSC.<br />

A recent study of specialist medical officer migration (Oman 2007) ‘Should I migrate or<br />

should I remain? Professional Satisfaction and career decisions of doctors who have<br />

undertaken specialist training in <strong>Fiji</strong>’ based on 3 elements of professional growth, service<br />

and recognition. Dissatisfaction was directed primarily at the MoH and the failure to reliably<br />

provide basic medications and supplies, as well as problems of career advancement created<br />

by bottleneck from limited numbers of senior postings. Oman’s also found a ‘centrality of<br />

the professional values of service, patient welfare regardless of ability to pay’ as a very great<br />

advantage from the standpoint of the MoH’ and goes on to propose 3 intervention areas to<br />

improve retention: supporting the work of doctors, supporting professional development and<br />

career advancement and valuing and supporting doctors as members of families, extended<br />

families and communities.<br />

9

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

3.3.4. Training the Clinical Workforce<br />

There are two major clinical training institutions in <strong>Fiji</strong> – the <strong>Fiji</strong> School of Medicine and the<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> School of Nursing. Annex 7 shows the output from these two major training institutions.<br />

It must be remembered that FSMed also serves as a regional training centre and that only<br />

60% of medical graduates are from <strong>Fiji</strong> (64% in <strong>2008</strong>).<br />

It has already been discussed that simply graduating new doctors or nurses will not address<br />

the immediate shortage of senior staff. As shown in tables 5 and Annex 8, the number of new<br />

<strong>Fiji</strong> medical graduates is almost matched by the number of doctors exiting the service.<br />

FSN and FSMed have consistently increased their intakes in response to the demonstrated<br />

needs arising from migration and high turnover – and the ever increasing need for <strong>Fiji</strong> to<br />

engage contracted foreign doctors. Unfortunately it is not possible to develop any specific<br />

“formula” to determine the number of staff that need to be trained to overcome losses. This is<br />

because the numbers leaving the services vary very significantly from year to year eg after<br />

political events such as a coup or after “recruitment drive”, by representatives from other<br />

countries eg the United Arab Emirates.<br />

Nevertheless this need to train more doctors should continue, even though data presented<br />

earlier in this report indicates that there is currently a slight surplus against establishment of<br />

the more junior levels of medical officer. This must be interpreted cautiously. There is a need<br />

to replace many of the lower level contracted foreign doctors in both <strong>Fiji</strong> and the PICs, and<br />

the need to consider contracting more senior medical staff at specialist, senior, chief and<br />

principle levels to improve the quality of health care services and also to support the training<br />

of local medical staff.<br />

Obviously the need to continue to train medical specialists through the Postgraduate Masters<br />

and Diploma level course at the FSMed should continue and indeed be given an even higher<br />

priority.<br />

Recommendation 1<br />

Continued efforts need to be made to increase the number of medical post-graduates from the<br />

FSMed, With this in mind, the IGOF should continue to allocate priority for postgraduate<br />

medical training when it allocates scholarships, either those that are internally funded or<br />

funded by its development partners.<br />

Recommendation 2<br />

The MoH should continue to work with the PSC to improve the salaries, allowances and<br />

incentives offered to specialist medical officers and specialist nurses with a view to reducing<br />

the level of outward migration and retaining their services within the <strong>Fiji</strong> health sector.<br />

3.4. Financing the health system<br />

From the outset it is important to note that the financial figures presented in this report have<br />

been vetted by the National Planning Office but there may be some discrepancies from those<br />

in the MoH accounts.<br />

3.4.1. Overview<br />

<strong>Health</strong> services in <strong>Fiji</strong> are primarily provided by government and financed almost exclusively<br />

through tax revenues. Other sources of funding for the MoH are donor assistance for service<br />

enhancements, a small cost-recovery program of user charges, a revolving drug fund account<br />

(from community pharmacies) and the government pharmacy’s bulk purchasing scheme.<br />

10

<strong>Situational</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> of the <strong>Fiji</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Sector</strong> December <strong>2008</strong><br />

Government allocations to the MoH vary according to policy and fiscal priorities. Developed<br />

countries spend in the order of 7% to 10% of GDP on health). <strong>Fiji</strong>’s government allocation of<br />

2.6% of GDP is the lowest among <strong>Pacific</strong> regional neighbours (UNDP 2007/<strong>2008</strong>). The<br />

Solomon Islands and Tonga allocate between 5-6% of GDP to health annually, Samoa<br />

between 4-5% and Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea over 3%. Table 6 illustrates that in <strong>Fiji</strong>,<br />

the proportion of GDP allocated to health has fluctuated around 3% but has fallen below that<br />

since the year 2000, placing pressure on the capacity to provide a quality national health care<br />

system and to continually upgrade it. This ongoing financial constraint is of major concern.<br />

The collection of fees for services provided to patients and others remains a strategy for<br />

raising revenues, but the existing fee structure allows for only a token level of cost recovery,<br />

down from 14% in 1962 to less than 1% of expenditure since 1992.<br />

Table 6. GDP, MoH budget and MoH budget as % of GDP, 1993-2005.<br />

Fiscal Year<br />

GDP ($ MOH Budget MoH Budget as %<br />

millions) (Million FJD) of GDP<br />

1993 1707.00 68.57 4.02<br />

1995 2799.00 78.11 2.79<br />

1999 3662.00 107.90 2.95<br />

2000 3505.00 124.20 3.54<br />

2003 4245.00 136.88 3.22<br />

2005 4731.00 136.88 2.89<br />

2006 5032.00 147.06 2.92<br />

2007 5079.00 142.67 2.81<br />

<strong>2008</strong> 5826.00 150.00 2.57<br />

Source: Bureau of Statistics, <strong>Fiji</strong> and <strong>Fiji</strong> Budget Estimates<br />