Performing Identities in Urban Spaces; Kampala, Uganda - Royal ...

Performing Identities in Urban Spaces; Kampala, Uganda - Royal ...

Performing Identities in Urban Spaces; Kampala, Uganda - Royal ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

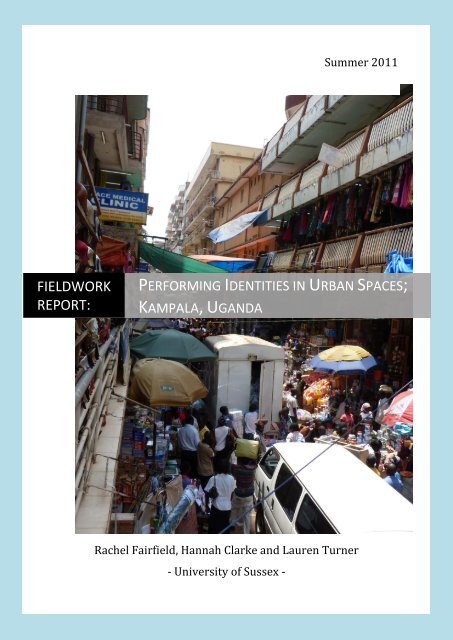

Summer 2011<br />

FIELDWORK<br />

REPORT:<br />

PERFORMING IDENTITIES IN URBAN SPACES;<br />

KAMPALA, UGANDA<br />

Rachel Fairfield, Hannah Clarke and Lauren Turner<br />

- University of Sussex -

Acknowledgements<br />

We would like to thank the <strong>Royal</strong> Geographical Society, without whom this research<br />

would not have been possible; the staff and students of the School of Women and<br />

Gender Studies at Makerere, and Mr Ronald Kalyango and Dr.Consolata Kabonesa <strong>in</strong><br />

particular; Evelyn Dodds, Grace Carswell and Mike Collyer at the University of Sussex<br />

for all of their help over the last two years. Most importantly we want to thank the<br />

participants of this study for their enthusiastic participation <strong>in</strong> this research project, for<br />

giv<strong>in</strong>g their time so will<strong>in</strong>gly and welcom<strong>in</strong>g us so k<strong>in</strong>dly.<br />

The purpose of our fieldwork<br />

This fieldwork was designed to uncover the ways <strong>in</strong> which identities are (re)produced<br />

and constructed with<strong>in</strong> and through urban spaces and <strong>in</strong>stitutions. This was a group<br />

research project <strong>in</strong>tended to <strong>in</strong>form three separate f<strong>in</strong>al-year undergraduate theses at<br />

the University of Sussex. It was conducted <strong>in</strong> association with the School of Women and<br />

Gender Studies at Makerere University, <strong>Kampala</strong>.<br />

The Research Team<br />

Rachel Fairfield – Rachel’s particular <strong>in</strong>terest was <strong>in</strong> the experience of female students<br />

at Makerere University, the <strong>in</strong>tersection of the different strands of gender, faith and age<br />

identites that were narrated and performed.<br />

Hannah Clarke – Hannah was <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> the (re)construction of gendered identities<br />

and stereotypes with<strong>in</strong> school spaces, and the various power relations that help to<br />

(re)enforce gender <strong>in</strong>equalities.<br />

Lauren Turner – As a student of Development Studies, Lauren focussed primarily on the<br />

role of Christian identity and church culture <strong>in</strong> a develop<strong>in</strong>g context.<br />

Ronald Kalyango – As a lecturer at the School of Women and Gender Studies at the<br />

University of Makerere, Ronald Kalyango, acted as a gatekeeper. He enabled us to make<br />

contact with <strong>in</strong>itial participants and formally <strong>in</strong>troduced us to other <strong>in</strong>stitutions (see<br />

appendix 1). As a team member, he was vital <strong>in</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>g our safety <strong>in</strong> country and<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>ed our first po<strong>in</strong>t of call regard<strong>in</strong>g health and safety issues.<br />

1

Research Site<br />

The <strong>Uganda</strong>n capital city of <strong>Kampala</strong> is a diverse cultural, l<strong>in</strong>guistic, religious and ethnic<br />

landscape that provides an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g location for the study of identity. <strong>Kampala</strong><br />

constitutes the ideal research site as English is widely spoken, render<strong>in</strong>g research more<br />

accessible. This fieldwork was conducted <strong>in</strong> August/September 2011 based on data<br />

collected at the University of Makerere, Watoto and Life Church and St Annes Secondary<br />

School 1 .<br />

Map of Research Site<br />

Watoto Church Central<br />

University of Makerere<br />

Life Church<br />

Methodology<br />

We used a triangulation of qualitative and quantitative methods and sampl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the<br />

field to help critically analyse the performance of identity that is <strong>in</strong>evitably complex and<br />

1 For ethical reasons the names have been changed of all of participants at the school and the locations that<br />

might reveal their identities, as agreed with the school<br />

2

difficult to measure. The employment of these divergent methods was beneficial as they<br />

produced outcomes that were unanticipated and directed the focus of our research.<br />

To ga<strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>-depth understand<strong>in</strong>g of the ways <strong>in</strong> which identities are experienced,<br />

(re)constructed and performed, a qualitative methodology was favoured. Us<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

qualitative methodology is well suited to the research of lived experiences, as it allows<br />

one to locate the mean<strong>in</strong>gs which different people place on particular events and<br />

structures (Muhanguzi 2011:715). This research took a case study approach, analys<strong>in</strong>g<br />

one particular school as examples, and makes no assumption of be<strong>in</strong>g statistically<br />

representative (Van Donge 2006:184).<br />

Participant observation<br />

Observ<strong>in</strong>g the everyday behaviour of pupils and staff at St Annes, students at Makerere<br />

and church attendants, allowed us to ga<strong>in</strong> a deeper <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to the dynamics of their<br />

everyday experience. Observations were taken dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons and lectures, at church<br />

services and events, and more generally around <strong>Kampala</strong>. Casual, <strong>in</strong>formal<br />

conversations and observations were used to complement formal data collected. This<br />

also allowed us to see any discrepancies between what was said <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews and real<br />

life experiences (Van Donge 2006:182).<br />

Quantitative Survey<br />

A prelim<strong>in</strong>ary survey was conducted with the aid of the St Anne’s Geography teacher,<br />

who also helped to expla<strong>in</strong> the nature and purpose of the research to the students. The<br />

survey, completed by 99 students, was designed to give an <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

attitudes of students towards school<strong>in</strong>g and their perceptions of gender differences,<br />

rather than to provide any significant quantitative data. As such, it is only briefly<br />

mentioned <strong>in</strong> the analysis.<br />

Interviews<br />

Interviews were semi-structured, allow<strong>in</strong>g the participants to shape the direction of the<br />

conversation, whilst ensur<strong>in</strong>g that key themes of the research were discussed (Kane<br />

1995:165).<br />

3

At St Annes, <strong>in</strong>terviews were conducted <strong>in</strong> groups of two to four, which allowed<br />

students to feel at ease and comfortable answer<strong>in</strong>g questions. This meant that a greater<br />

number of discussions could be consolidated <strong>in</strong>to a shorter space of time than would be<br />

needed for <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>terviews. Interviews were predom<strong>in</strong>antly conducted <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>glesex<br />

groups, with two mixed groups to offer diversity.<br />

Group Interviews and Focus Groups<br />

Re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terviews with focus groups <strong>in</strong>dorsed greater depth and understand<strong>in</strong>g;<br />

personal perspectives developed as participants were able to feed from one another,<br />

deliberate and consider new, alternative suppositions. The <strong>in</strong>tense dialogue proved<br />

time efficient when collat<strong>in</strong>g data yet m<strong>in</strong>imised <strong>in</strong>terference from ourselves. Focus<br />

groups empowered participants to direct discussion whilst we observed <strong>in</strong>teraction,<br />

thus facilitat<strong>in</strong>g comprehension on a spectrum of experiences with<strong>in</strong> the social and<br />

geographical context.<br />

Life Histories<br />

Life histories were collected and recorded with six female students liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kampala</strong>,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g undergraduates, graduates and mature students from Makerere University.<br />

The aim of life histories is to give a voice to those stories and biographies that otherwise<br />

go untold and unheard (Perks and Thomson, 1998: 101). This qualitative technique<br />

allowed <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>formants to narrate and give mean<strong>in</strong>g to their unique experiences<br />

and provided us with rich material and transcriptions on the topic of the performance of<br />

identity.<br />

Sampl<strong>in</strong>g / Participant Selection<br />

Strike action at the University of Makerere and the resultant closure of the University<br />

meant that rather than apply<strong>in</strong>g a formal sampl<strong>in</strong>g strategy to ga<strong>in</strong> access to a crosssection<br />

of the community, we <strong>in</strong>stead used ‘snowball sampl<strong>in</strong>g’ (Kitch<strong>in</strong> and Tate 2000).<br />

In an unfamiliar culture and whilst discuss<strong>in</strong>g potentially sensitive issues we all<br />

considered this the most appropriate method to utilise. Initially our gatekeeper<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced us to participants through whom we were able to network and secure<br />

additional <strong>in</strong>terviewees, and students who were <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> tak<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>in</strong> the life<br />

4

histories, thus avoid<strong>in</strong>g any narrow direction <strong>in</strong> which us<strong>in</strong>g only a gatekeepers’<br />

contacts may <strong>in</strong>cur.<br />

At all times, when approach<strong>in</strong>g participants we ensured written or verbal consent was<br />

granted. In so do<strong>in</strong>g, we firstly revealed a little about ourselves, presented clearly the<br />

aims of our fieldwork and the <strong>in</strong>tended focus of discussions. We expla<strong>in</strong>ed our<br />

commitment to confidentiality and their right to withdraw at any time throughout the<br />

research process. We further clarified the expected duration of <strong>in</strong>terviews or focus<br />

groups and ensured every participant understood all of the above before proceed<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

It was important to <strong>in</strong>terfere as little as possible with the ord<strong>in</strong>ary, everyday runn<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

the school, University and Church. To ga<strong>in</strong> as true an <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to different experience as<br />

possible, but also to not be a burden the <strong>in</strong>stitutional management or obstruct pupils’<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g, this research was conducted flexibly and adhered to no rigid sampl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

strategy. Interviews were conducted <strong>in</strong> free periods and break times, with those pupils<br />

and students who volunteered.<br />

Wider Significance<br />

This research is not <strong>in</strong>tended to be representative of any group other than those who<br />

participated <strong>in</strong> it. In fact, it is written as evidence of the multiplicity of peoples<br />

experiences, as an example of the ways <strong>in</strong> which different <strong>in</strong>dividuals experience and<br />

understand their identifications and their position <strong>in</strong> society <strong>in</strong> different ways.<br />

5

Key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs:<br />

The <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g focus on identity <strong>in</strong> western academia is <strong>in</strong>dicative of its importance;<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluential and nuanced work puts identity and the <strong>in</strong>dividual at the centre of human,<br />

social and cultural geographical concern (Hall 1992; Butler 1990; Valent<strong>in</strong>e 2001; Pa<strong>in</strong><br />

2001; Little 2002; Jackson 2005). Poststructuralists’ have moved away from static and<br />

essentialist notions of identity, towards an understand<strong>in</strong>g of self that is socially<br />

constructed, shift<strong>in</strong>g and multiple (Little 2002:35), expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the ways <strong>in</strong> which<br />

identities are fragmented, dislocated and de-centred, rather than stable, s<strong>in</strong>gle and<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrated, <strong>in</strong>fluenced by multiple cultural landscapes (Hall 1992: 274). <strong>Identities</strong> are<br />

constructed and transformed by dom<strong>in</strong>ant categories of gender, class, age and faith;<br />

they are a site of constant negotiation, affected by expectations of ‘appropriate’ and<br />

‘<strong>in</strong>appropriate’ behaviours or dress.<br />

The role of Space and Institutions<br />

Though conventionally <strong>in</strong>stitutions such as schools and universities have been thought<br />

of as stable, built environments made of bricks and mortar, more recent studies<br />

reconceptualise <strong>in</strong>stitutions as networks of resources, knowledge and power; which<br />

both transform and are transformed by the people and places which create and susta<strong>in</strong><br />

them (Valent<strong>in</strong>e 2001:141-2). The school as a social <strong>in</strong>stitution is understood, therefore,<br />

not as a bounded entity, but as a network of power relations; between the students,<br />

their families, the staff, the government and the spaces they <strong>in</strong>teract <strong>in</strong> and across.<br />

Institutions, such as schools, become characterised by power relationships of control<br />

and discipl<strong>in</strong>e (Holloway and Hubbard 2001:187) and thus (re)produce social<br />

hierarchies and <strong>in</strong>equalities. With<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions particular behaviours and attitudes<br />

become “predictable and rout<strong>in</strong>e” and are thus <strong>in</strong>stitutionalised (Goetz 1997:5).<br />

Social and fem<strong>in</strong>ist geographers are <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> the ways <strong>in</strong> which identities and<br />

spaces are constructed and gendered through performance (Little 2002:36). Social<br />

identities and subjectivities are “<strong>in</strong>timately tied to the spaces through which people<br />

practice and perform them” and are constructed <strong>in</strong> relation to systems of authority<br />

which mark out the behaviours and identities which are deemed “appropriate” and<br />

“<strong>in</strong>appropriate” (Del Cas<strong>in</strong>o 2009:203). Powerful agents <strong>in</strong> society control the way<br />

spaces are constructed and as such they reflect the structural hierarchies of society<br />

6

(Holloway and Hubbard 2001:190). Holt studied the ways <strong>in</strong> which (dis)abled identities<br />

are (re)constructed through discursive and performative practices <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>stream<br />

primary schools (2004:220). Her research demonstrates how the spaces of education<br />

develop “hidden curricula which ‘teach’ children appropriate identity position<strong>in</strong>gs”<br />

which are both gendered and (hetero)sexualised (Holt 2004:226). This hidden curricula<br />

is not consciously enforced, but produced through the performance of dom<strong>in</strong>ant and<br />

marg<strong>in</strong>al identities (ibid). Gender identities and relations are negotiated and enforced<br />

through this hidden curriculum (Dunne et al. 2006:78). Schools thus help to reproduce<br />

the established social order as classrooms regulate children’s bodies and behaviour <strong>in</strong>to<br />

particular (hetero-normative) rout<strong>in</strong>es and practices (Del Cas<strong>in</strong>o 2009:202).<br />

Space plays an active role <strong>in</strong> the construction of identity where particular behaviours,<br />

activities and beliefs are deemed appropriate through cultural understand<strong>in</strong>gs and<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs of particular places such as social <strong>in</strong>stitutions, the communities,<br />

neighbourhoods, homes, shops, clubs and cafes all acquire mean<strong>in</strong>g through different<br />

identifications (Pa<strong>in</strong>, 2001:141). The spatial divisions <strong>in</strong> the social <strong>in</strong>stitution of the<br />

university created boundaries between and with<strong>in</strong> groups. The data presented multiple,<br />

<strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g identities that were constantly <strong>in</strong> a process of formation. (Jackson 2005).<br />

The performance of female student identity on campus was a complicated course of<br />

study to explore. The <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ities, ethnicities, ages, and religions played a<br />

central part <strong>in</strong> the students’ day to day lives. The performance and enactment of identity<br />

was explored through the <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g categories of gender, faith and the role of dress.<br />

Gender is a key part of identity and self-identification. Butler’s term ‘performativity’ has<br />

been used to explore the gender roles where performativity is def<strong>in</strong>ed as: “a repetition<br />

and a ritual, which achieves its effects through its naturalization <strong>in</strong> the context of the<br />

body, understood <strong>in</strong> part, as a culturally susta<strong>in</strong>ed temporal duration” (1999: XV). This<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ition exemplifies that gender norms and roles are <strong>in</strong>ternalised <strong>in</strong> the body through<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>ed and repeated acts <strong>in</strong> mundane day to day life. The term ‘performativity’ can<br />

be broadened to explore other <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g axes of identity that are performed<br />

simultaneously.<br />

Six life histories with female students were conducted and revealed the ways <strong>in</strong> which<br />

girls experience campus life across different spatial and temporal contexts. After talk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

7

to undergraduate and postgraduate students we observed that they develop a dynamic<br />

self-awareness. Female students narrated a sense of belong<strong>in</strong>g and a sense of self<br />

through their lived and emotional experiences at home and at university. The<br />

<strong>in</strong>tersection of gender, age and faith <strong>in</strong>fluence and shape the experience of “student” or<br />

“campus” life, as they are performed on a day to day basis. The performance of gender<br />

was presented amongst the female students through their activities that took place <strong>in</strong><br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle-sex gender groups, for example: cook<strong>in</strong>g, clean<strong>in</strong>g, wash<strong>in</strong>g clothes, study<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

worship, shopp<strong>in</strong>g, socialis<strong>in</strong>g, clubb<strong>in</strong>g and look<strong>in</strong>g after k<strong>in</strong> relations. Traditional<br />

cook<strong>in</strong>g was a skill passed down from the female’s mothers or aunties where the<br />

cultural norm is that young girls will take on the domestic work when they start their<br />

own families. These daily rout<strong>in</strong>es, rituals and practices reflect cultural norms and<br />

values that are naturalised and <strong>in</strong>ternalised; they are taken-for-granted (Butler 1990).<br />

The various forms of accommodation on campus (and just outside the site) were<br />

spatially gendered; the majority of them s<strong>in</strong>gle-sex ‘hostels’. The female students were<br />

able to make friends and create social networks with the people <strong>in</strong> their hostels from<br />

different religious and ethnic-tribe backgrounds. Study groups or ‘circles’ were set up<br />

depend<strong>in</strong>g on what hall or hostel and from what faculty; this built up friendships from<br />

an early stage. The construction of gender relations can be analysed here as central ”to<br />

the spatial organisation of social relations” (Massey Cited <strong>in</strong> Callard 2004:220).<br />

Therefore, multiple public and private spaces and places construct experiences and<br />

shape gendered performances and different mean<strong>in</strong>gs of fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ity.<br />

The dom<strong>in</strong>ance of religion <strong>in</strong> the female student’s lives was evident <strong>in</strong> the construction<br />

of space and place. Students were encouraged to attend weekly and daily services and<br />

participate <strong>in</strong> events and celebrations. In addition, the Anglican and Catholic Churches<br />

ran mid-week services for students, choir practices and usher met on Saturdays and<br />

Communion and Morn<strong>in</strong>g Prayer for the public was on Sundays. Similarly, the Mosque<br />

on campus and the Makerere University Muslim Students’ Association (MUMSA) had<br />

different events for the Muslim freshers. In the Mosque they had daily prayer five times<br />

a day and weekly prayer every Friday. When talk<strong>in</strong>g to undergraduates about their<br />

experiences of start<strong>in</strong>g university, most of the students referred to the religious<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutions be<strong>in</strong>g a source of comfort and identification.<br />

8

The social space of the Mosque is gendered where the boys pray down stairs and the<br />

girls pray upstairs. It was observed that the girls could sit <strong>in</strong> the same room for<br />

particular conventions but there was a clear divide and separation. Female MUMSA<br />

committee members emphasised how the association had strengthened their faith as<br />

female Muslims. The ‘Women’s Vision’, a programme for female Muslim students is run<br />

by former students who discuss their experiences and advise any students who may be<br />

struggl<strong>in</strong>g with issues such as f<strong>in</strong>ance, study<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g Ramadan and mak<strong>in</strong>g friends.<br />

Both these examples highlight the <strong>in</strong>tersection of gender and faith which created a<br />

sense of community and belong<strong>in</strong>g for the students. Religion appeared to be very<br />

important <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kampala</strong>; the diverse religious landscapes seemed to coexist <strong>in</strong> relative<br />

harmony, where people respected others beliefs and practices. Many students talked<br />

openly about people convert<strong>in</strong>g to different religions out of personal choice. This was<br />

accepted <strong>in</strong> society as long people conformed to the particular religious groups that<br />

populated <strong>Kampala</strong>, the majority be<strong>in</strong>g Christians and Muslims and m<strong>in</strong>ority be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

H<strong>in</strong>dus and Sikhs. The faith identities of be<strong>in</strong>g a Born-aga<strong>in</strong> Christian, Anglican, Catholic<br />

or Muslim were performed <strong>in</strong>dividually and collectively on a daily basis and <strong>in</strong>tersected<br />

with the identity of be<strong>in</strong>g a female student. This addresses the <strong>in</strong>terconnections<br />

between social categorizations where space and place are significant <strong>in</strong> the process of<br />

subject formations (Valent<strong>in</strong>e: 2007: 11). The gendered division of education, social<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutions and social activities was clearly presented.<br />

A number of studies have shown the ways <strong>in</strong> which gender <strong>in</strong>equities can be (and are)<br />

(re)constructed and (re)enforced with<strong>in</strong> schools <strong>in</strong> Sub-Saharan Africa (Jones 2011;<br />

Muhanguzi 2011; Dunne 2007; Dunne et al. 2006; Mirembe and Davies 2001).<br />

Consistent with the situation globally, <strong>Uganda</strong>’s schools are gendered spaces through<br />

which discourses of conformity (re)enforce power imbalances and create pressure for<br />

boys and girls to be “normal”. They are sites of constant surveillance, where<br />

“appropriate” behaviour is rewarded and undesirable or “<strong>in</strong>appropriate” behaviour is<br />

punished (Holloway and Hubbard 2001:186). It was fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g to see the ways <strong>in</strong><br />

which gender discourses were played out <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Uganda</strong>n secondary school. Through<br />

fieldwork <strong>in</strong> a “third class” fee-pay<strong>in</strong>g school, we were able to ga<strong>in</strong> an understand<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

9

the ways <strong>in</strong> which staff and pupils (re)produce and naturalise certa<strong>in</strong> power relations<br />

such as between teachers and pupils, and males and females through their everyday<br />

actions and conversations with<strong>in</strong> school spaces.<br />

The <strong>Uganda</strong>n government has been <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly engaged with gender issues, and has<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced a number of policies <strong>in</strong>tended to <strong>in</strong>crease gender parity <strong>in</strong> schools and<br />

universities (Molyneaux 2011; Jones 2011). This has created a discourse around gender<br />

<strong>in</strong>equality that means people <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> are aware of the issues, but does not necessarily<br />

mean that the complexities of gender are understood by all people, or that anyth<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g actively done to affect change. It has been noticed elsewhere that new policies<br />

frequently fail because those responsible for implementation at a school level fail to do<br />

their part (Chapman et al. 2010:78). The teachers at St Annes School had not received<br />

any tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> gender. Despite be<strong>in</strong>g a young staff, several of whom were only one or<br />

two years <strong>in</strong>to their teach<strong>in</strong>g careers, they had received no practical tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> terms of<br />

recognis<strong>in</strong>g or prevent<strong>in</strong>g an unequal school dynamic, nor were they enrolled <strong>in</strong> any<br />

upcom<strong>in</strong>g gender programme.<br />

Reflexive of the situation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> generally, school leadership tends to be patriarchal<br />

and males tend to dom<strong>in</strong>ate all formal positions of power (Mirembe and Davies<br />

2001:404). At St Annes there were only two female teachers, both of whom were part<br />

time and one of which was not present dur<strong>in</strong>g our time there. The head teacher and<br />

others <strong>in</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istration were all male, as was the teacher nom<strong>in</strong>ated as “counsellor”<br />

who was the students’ official po<strong>in</strong>t of contact for any compla<strong>in</strong>ts or problems. In<br />

several areas, the staff and students believed the school policy was gender neutral, with<br />

regards to prefects it was said that girls and boys had equal roles and were equally<br />

represented on committee. However, the treasurer is always male and the secretary is<br />

always female. This was not recognised as a case of gender stereotyp<strong>in</strong>g, but just ‘the<br />

way th<strong>in</strong>gs are’, the natural order of th<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

These gender dynamics are embedded <strong>in</strong> the norms and practices of the school<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitution so thoroughly that they rema<strong>in</strong> largely unquestioned (Goetz 1997:5).<br />

“Mascul<strong>in</strong>e dom<strong>in</strong>ance” is re<strong>in</strong>forced and girls subord<strong>in</strong>ated through the gender<br />

segregation of power and responsibilities (Dunne 2007:505). Several girls<br />

10

acknowledged the <strong>in</strong>equality implicit <strong>in</strong> a girl be<strong>in</strong>g refused a position as head prefect<br />

purely on the basis if her gender, but felt powerless to affect change. The normalisation<br />

of male leadership at St Annes silenced their objections, allow<strong>in</strong>g the school to re<strong>in</strong>force<br />

hegemonic male leadership. Mirembe and Davies (2001) saw this unequal distribution<br />

of responsibility, whereby girls are underm<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the school decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

processes, as worry<strong>in</strong>g. Young girls at school are learn<strong>in</strong>g to be dependent on boys as<br />

leaders, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the power imbalance between boys and girls, mak<strong>in</strong>g them<br />

vulnerable to exploitation (Mirembe and Davies 2001:406).<br />

It became clear – through observations and <strong>in</strong>terviews - that male students dom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

classroom space and conversation, and <strong>in</strong>-l<strong>in</strong>e with other studies, they tended to ga<strong>in</strong><br />

more attention from teachers dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons (Ga<strong>in</strong>e and George 1999:42). Students<br />

seat<strong>in</strong>g arrangements were not controlled by teachers but are reflective of students’<br />

active role <strong>in</strong> gender segregation (Dunne 2007:506). With the exception of Senior 5 and<br />

6 (where student numbers were very low), the back few rows of tables <strong>in</strong> every<br />

classroom were exclusively occupied by boys, whilst girls and the few rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g boys<br />

took their seats <strong>in</strong> the rest of the class. Just as <strong>in</strong> Dunne’s research, teachers reiterated<br />

gender stereotypes when expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g this phenomenon, say<strong>in</strong>g that it was because of the<br />

opportunity for misbehaviour that boys sat at the back, whilst girls were cast as more<br />

“compliant, co-operative and attentive” (Dunne 2007:507). In the lower classes <strong>in</strong><br />

particular this seat<strong>in</strong>g layout felt <strong>in</strong>timidat<strong>in</strong>g, as older, bigger males sat at the back of<br />

the class ‘over-see<strong>in</strong>g’ the other students and creat<strong>in</strong>g an uncomfortable atmosphere.<br />

The fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ity emphasised by girls - quiet, sensible, well behaved, gives power to boys<br />

who position themselves as louder and less-well behaved (Paechter 1998:20). It<br />

appeared that girls <strong>in</strong> the lower classes (S1-4) felt shy to talk up <strong>in</strong> classrooms, however<br />

outside of class girls were often more conscientious. This relies on girls tak<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiative and hav<strong>in</strong>g the confidence to approach teachers outside of class and so does<br />

not necessarily counteract the effects of male classroom dom<strong>in</strong>ation, though it is<br />

evidence that pupils negotiate school spaces and relations <strong>in</strong> diverse ways.<br />

11

The Experience of Home<br />

University and school were significant discursive places where students created and<br />

negotiated their identifications. Similarly, the home was a discursive place where<br />

females’ everyday choices were shaped by <strong>in</strong>timate ties <strong>in</strong> community and amongst k<strong>in</strong><br />

that <strong>in</strong>fluenced their decision mak<strong>in</strong>g. The significant social relations and social spaces<br />

and places shaped and co-produced their identities.<br />

An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of this research is the extent to which the pupils at St Annes were<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced by their familial experience and by their experience of male and female role<br />

models. Traditionally, <strong>Uganda</strong> is a patriarchal society, and education has historically<br />

been the preserve of male children, as female children were <strong>in</strong>stead married young or<br />

expected to support their mothers <strong>in</strong> the domestic runn<strong>in</strong>g of the home (Mirembe and<br />

Davies 2001:402). Though attitudes are chang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>, it is still the boy-child<br />

whose education is favoured <strong>in</strong> a majority of homes 2 . One teacher said that this is<br />

because “ladies are still blamed for be<strong>in</strong>g pregnant” and so their employment<br />

opportunities are much more restricted than males. As such, many parents cannot see<br />

the value <strong>in</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g their daughters.<br />

A significant number of girls spoke of a lack of support from male role models – fathers<br />

or older male family members – say<strong>in</strong>g that it is their mothers who support them<br />

through school, whilst their fathers leave and have little, if any, contact with their<br />

children. Many students came from female-headed households, where their mothers<br />

were either widowed, separated or divorced, or had polygamous husbands who spread<br />

their time between a number of homes. Many of the girls held very negative views of<br />

men, which necessarily affected their relations with, and expectations of, boys and men<br />

at school. For many girls it was a negative experience of fathers, or vulnerability to<br />

abuse or exploitation from other older males, that encouraged them to cont<strong>in</strong>ue their<br />

education. They recognised complet<strong>in</strong>g school and educat<strong>in</strong>g themselves as an<br />

important way of m<strong>in</strong>imis<strong>in</strong>g the risk of exploitation.<br />

2 Ratio of female to male secondary enrolment (% gross) was at 85% <strong>in</strong> 2010 <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>; Girls<br />

enrolment was at 26%, whilst the boys was 30%. “Gross enrolment ratio is the ratio of total<br />

enrolment, regardless of age, to the population of the age group that officially corresponds to the<br />

level of education shown” (World Bank 2012)<br />

12

Several participants suggested that there has been a shift <strong>in</strong> recent years, and a grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

tendency among parents to see the girl-child and boy-child as equal. It was suggested<br />

that this is perhaps a response to see<strong>in</strong>g a woman as Vice-President, or due to <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

hav<strong>in</strong>g a female Speaker of Parliament. See<strong>in</strong>g that other women have succeeded <strong>in</strong><br />

becom<strong>in</strong>g successful and powerful through education may be <strong>in</strong>spirational for young<br />

girls at school. Women are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>n politics and decisionmak<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

though they rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>ority. Women make up 24% of cab<strong>in</strong>et members<br />

and 31% of MPs, though they only account for 17% of senior government positions and<br />

<strong>in</strong>equalities still exist <strong>in</strong> property ownership and access to resources and economic<br />

opportunities (UN 2009:9).<br />

Traditional gender roles dictate that women are responsible for most of the domestic<br />

work around the home and earn their liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> gender-specific jobs such as tailor<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

cook<strong>in</strong>g, or through sell<strong>in</strong>g fruits and vegetables. Meanwhile men are employed <strong>in</strong><br />

markets, bus<strong>in</strong>esses, construction work, driv<strong>in</strong>g taxis and boda-bodas: <strong>in</strong>come<br />

opportunities not deemed appropriate for women. At home, the majority of girls<br />

<strong>in</strong>terviewed were expected to help with chores <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g prepar<strong>in</strong>g meals, wash<strong>in</strong>g<br />

clothes, mopp<strong>in</strong>g, sweep<strong>in</strong>g and clean<strong>in</strong>g before they are able to attend to their<br />

homework. Whilst boys also have chores – most commonly fetch<strong>in</strong>g water or logs – it<br />

was the girls who found these chores a particular disadvantage, as their duties were<br />

time consum<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the experiences of participants economic lack is the ma<strong>in</strong> barrier to<br />

receiv<strong>in</strong>g a good level of education. This difficulty is experienced <strong>in</strong> different ways<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to a person’s identity, their family background, class, age and <strong>in</strong> particular<br />

their gender. Though both sexes struggle to f<strong>in</strong>d school fees, it is easier for male<br />

students to take on casual and manual work to earn money quickly. Several students<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>ed that jobs considered appropriate for girls, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g domestic and shop work,<br />

require such long hours and commitment that it would not be possible to work<br />

alongside school<strong>in</strong>g. Instead, many rely on hand-outs from older, earn<strong>in</strong>g males - often<br />

“boda-boda” (motorcycle) drivers - putt<strong>in</strong>g them at risk of unwanted pregnancy and<br />

sexually transmitted <strong>in</strong>fections. The discourse surround<strong>in</strong>g employment therefore<br />

13

creates a cyclical problem as girls drop out of school without complet<strong>in</strong>g, thus<br />

susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and reproduc<strong>in</strong>g the gender <strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> education.<br />

Embodiment<br />

Clothes or ‘dress’ constitutes an essential part of shap<strong>in</strong>g the social body. Cultural,<br />

religious, ethnic, gender and generation identities are expressed visually and<br />

symbolically through dress, determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g who belongs and who does not. Dress was<br />

performed, enacted and embodied by the students, imbued with socio-cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(Barnes and Eicher, 1992).<br />

The female body can be conceptualised as a non-dualistic body where experiences are<br />

felt with<strong>in</strong> the body and m<strong>in</strong>d (Longhurst 1995). Embodied subjectivities allow a better<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>in</strong>dividual and unique experience that can be expressed through<br />

different narratives performed <strong>in</strong> space and place (1995:100). In this section I shall<br />

explore faith embodiment through the discourse on the veil <strong>in</strong> Islam. Where the cultural<br />

construction of the Muslim female body is understood and <strong>in</strong>fluenced by plural bodily<br />

techniques and behaviour. The discourse of veil<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>in</strong>formed through the social<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g of Islam, where there are multiple and contested mean<strong>in</strong>gs and practices of<br />

veil<strong>in</strong>g that vary across cultures (Dwyer, 2008).<br />

Faith and ‘The Veil’<br />

The embodiment of faith identities can be explored through the various forms of veil<strong>in</strong>g<br />

amongst Muslim girls on campus. From the different life histories we have gathered that<br />

the process of veil<strong>in</strong>g is perceived as be<strong>in</strong>g primarily about their devotion to Allah and<br />

subsequently about modesty. Female embodiment of the Muslim faith is presented<br />

through the veil which is culturally and religiously appropriate for girls and women to<br />

embody the Islamic value of modesty. Through the narrative performances the girls<br />

expressed their bodily experiences of physically and psychologically wear<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

adopt<strong>in</strong>g the veil. Their identities as Muslim women were produced, embodied and<br />

performed. Dur<strong>in</strong>g their <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>in</strong> their homes they did take off their veils <strong>in</strong> our<br />

presence and <strong>in</strong> front of other females dur<strong>in</strong>g prayer. The relationship of embodiment<br />

and place plays a part <strong>in</strong> the production of mean<strong>in</strong>g, where different public and private<br />

sett<strong>in</strong>gs require different mean<strong>in</strong>g and social learn<strong>in</strong>g of Islam and faith.<br />

14

Conclusions<br />

Identity can no longer be viewed as a s<strong>in</strong>gle coherent ‘self’; it is plural, where multiple<br />

identities are negotiated and constructed through space. Social and cultural theory on<br />

identity reveals identities to be relational to a number of th<strong>in</strong>gs (Hall, 1992). The female<br />

students and pupils <strong>in</strong>terviewed at the university, school and church and <strong>in</strong> their homes<br />

were <strong>in</strong>fluenced by social relations of significant people and different spatial and<br />

temporal contexts. The <strong>in</strong>formants <strong>in</strong>terviewed revealed an awareness of their<br />

subjective personhood and identity, but this was to a great extent <strong>in</strong>fluenced by their<br />

social and cultural contexts. The spatial divisions <strong>in</strong> the social <strong>in</strong>stitutions created<br />

boundaries between and with<strong>in</strong> groups. The data presented multiple, <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

identities that were constantly <strong>in</strong> a process of formation, <strong>in</strong>terchangeable and relational<br />

(Jackson: 2005). These identities are enacted, performed and embodied.<br />

The outcome of the empirical data revealed our <strong>in</strong>formants’ identities to be fragmented,<br />

dislocated and de-centred subjects, <strong>in</strong>fluenced by multiple cultural landscapes (Hall,<br />

1992: 274). From our observations presented <strong>in</strong> this study the students’ sense of self<br />

and personal identity was extended, shifted and transformed by the dom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

categories of gender, age and faith, and the role of dress, which were encountered on a<br />

daily basis. The university, school and church were significant discursive places where<br />

people created and negotiated these identity categories. The significant social relations<br />

and social spaces and places shaped and co-produced their identities.<br />

15

Fig 1:<br />

16

Fig 2:<br />

17

Fig 3:<br />

18

Fig 4:<br />

19

Fig 5:<br />

Limitations<br />

The method used produced a great deal of useful and <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g data, however there<br />

were a number of limitations which necessarily affected the material collected:<br />

Researcher Positionality:<br />

Our group identity as white European females was significant <strong>in</strong> this study and all data<br />

collected was necessarily affected by how we were viewed (Momsen 2006). There was a<br />

risk that the unequal power relations between a researcher from a wealthy country and<br />

participants <strong>in</strong> an impoverished area at a “poor” school could be problematic (Van Blerk<br />

2006:57; Harrison 2006:64). The effect of this was m<strong>in</strong>imised by several factors. The fact<br />

that I was known to be stay<strong>in</strong>g at an orphanage five m<strong>in</strong>utes from the school made my<br />

situation more relatable for participants - one boy from the orphanage also attended St<br />

Annes which helped make me a “known” entity. This, alongside the fact that I came to<br />

them as a student, appears to have m<strong>in</strong>imised the expectation of monetary benefits for<br />

participation (Van Blerk 2006:57). In fact, despite describ<strong>in</strong>g their struggles to f<strong>in</strong>d fees<br />

to attend school and the lack of resources, not a s<strong>in</strong>gle person at the school once asked<br />

me for so much as a pen.<br />

20

Students seemed quick to trust us, perhaps because we were work<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> a “known”<br />

environment. The fact that all <strong>in</strong>terviews were conducted <strong>in</strong> a space they knew well and<br />

at their convenience helped to ensure that they were comfortable and felt free to speak<br />

openly. The fact that we are all students helped us to be more approachable, particularly<br />

among the A-Level pupils whom we were close to age. As we were <strong>in</strong>troduced to the staff<br />

as students work<strong>in</strong>g with the School of Women and Gender Studies at Makerere (see<br />

appendix 1), they were able to view us as undergraduate students - a much less<br />

threaten<strong>in</strong>g identity than that of “foreign researcher”.<br />

Environment<br />

There is always a risk, particularly <strong>in</strong> school-based studies that students will provide<br />

answers that they “th<strong>in</strong>k you want to hear”, rather than giv<strong>in</strong>g true accounts of their<br />

experiences (Van Blerk 2006:55). Over the course of the <strong>in</strong>terviews, which <strong>in</strong> most cases<br />

were 45m<strong>in</strong>utes to an hour long, contradictory accounts were given and we have had to<br />

use our judgement and observations to determ<strong>in</strong>e the most likely truth (Harrison<br />

2006:65). Though every effort was taken to expla<strong>in</strong> to participants that there were no<br />

right answers and that the research was only <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> their real life experiences, it<br />

was important to analyse material gathered with this limitation <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d. It is also very<br />

possible that some pupils and students felt unable to speak freely for fear of gett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to<br />

trouble with the <strong>in</strong>stitutional authorities. This may also expla<strong>in</strong> why the majority of<br />

students were unwill<strong>in</strong>g to claim first-hand experience of, for example, relationships with<br />

teachers or older men, <strong>in</strong>stead report<strong>in</strong>g cases of other students who had become<br />

pregnant or been expelled.<br />

Conduct<strong>in</strong>g research <strong>in</strong> an unfamiliar cultural context proved challeng<strong>in</strong>g, especially <strong>in</strong><br />

the early phases. Although English is widely spoken, particular words and phrases needed<br />

def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, thus allow<strong>in</strong>g us to engage <strong>in</strong> a locally relevant manner and decipher<br />

participants’ <strong>in</strong>tended mean<strong>in</strong>g. For ethical reasons we avoided talk<strong>in</strong>g about sexuality<br />

and ethnicity because these were sensitive topics that were not openly talked about<br />

amongst our participants. These are important po<strong>in</strong>ts of analysis to consider when<br />

research<strong>in</strong>g identity <strong>in</strong> social geography which have been discussed <strong>in</strong> relation to gender<br />

and ‘race’ and are key components when study<strong>in</strong>g ‘young adults’.<br />

21

Gett<strong>in</strong>g acqua<strong>in</strong>ted with our surround<strong>in</strong>gs and ‘normal’ behaviour took time, which, while<br />

necessary, encroached upon research or network<strong>in</strong>g time. Our time <strong>in</strong> the field was<br />

restricted by University term times both <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> and the UK; we could not go to<br />

<strong>Kampala</strong> until term began due to our fourth (<strong>in</strong>-country) team-member be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

unavailable, and had to return <strong>in</strong> time for the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of the academic year at Sussex.<br />

Limitations were expected, thus we prepared for this by network<strong>in</strong>g prior to our arrival<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Kampala</strong>. Similarly, punctuality proved problematic, the phrase “this is Africa” (TIA)<br />

was frequently used <strong>in</strong> reference to participants be<strong>in</strong>g late for arranged meet<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

Altered plans<br />

We were unable to access Watoto Church because of all the bureaucracy <strong>in</strong> place, despite<br />

numerous meet<strong>in</strong>gs and communication before we arrived <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>. As a result our<br />

participant observation with<strong>in</strong> that organisation was limited and we were unable to ga<strong>in</strong><br />

more than a surface impression of their work<strong>in</strong>gs. Instead we made contact with another<br />

evangelical Church, which proved to be most fruitful.<br />

On the 1 st of September it was announced that the University of Makerere had been<br />

closed <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>itely as a result of strike action by university lecturers, and neither the<br />

media nor our contacts were able to anticipate when it would reopen. This was where<br />

our gatekeeper worked and where we were to meet many of our <strong>in</strong>itial participants; it<br />

was also where we were able to network and arrange meet<strong>in</strong>gs. The strike thus created<br />

many difficulties for the team. Due to the strikes we were not be<strong>in</strong>g able to fully explore<br />

the lived experience of “campus life”. We acknowledge that our aim to discover the<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence of the university as a social <strong>in</strong>stitution and its <strong>in</strong>fluence on <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g identity<br />

was limited.<br />

Campus was dangerous dur<strong>in</strong>g the strikes as there was threat of violence and ‘tear gas’,<br />

we overcame this by text<strong>in</strong>g students at Makerere to <strong>in</strong>quire as to the safety of travell<strong>in</strong>g<br />

through town onto campus.<br />

Methodology<br />

The use of a flexible sampl<strong>in</strong>g methodology and volunteerism obviously affected the data<br />

collected as it is likely that students who volunteered their spare time to answer research<br />

22

questions are likely to be among the most conscientious students so may not provide a<br />

representative sample of the student population. However volunteerism means that<br />

pupils did not feel obligated to participate because their teachers had sanctioned the<br />

research, thus avoid<strong>in</strong>g a tricky ethical dilemma (Van Blerk 2006:57).<br />

This research was undertaken <strong>in</strong> the first three weeks of a new school term, and numbers<br />

were low at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g as pupils “searched for fees”. It follows therefore that those<br />

pupils who were present at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of term are those who face the fewest barriers<br />

to access<strong>in</strong>g education, and pupils who were absent represent the students who face the<br />

greatest obstacles.<br />

Budget<br />

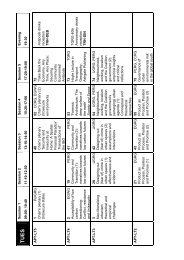

Below is a table show<strong>in</strong>g our total project expenditure for all liv<strong>in</strong>g costs and expenses<br />

for the duration of the project as well as pre-departure preparation.<br />

Daily Group Expenditure Group Total<br />

Flights £ 1,900.00<br />

First Aid Course £ 60.00<br />

Insurance £ 300.00<br />

Vacc<strong>in</strong>ations + Anti-Malarials £ 150.00<br />

Accommodation £ 16.80 £ 705.00<br />

Food and Travel £ 16.90 £ 680.00<br />

Visa £ 93.00<br />

Safari £ 573.00<br />

Total £ 4,461.00<br />

Incident Report<br />

We did not encounter any serious health or safety issues whilst <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kampala</strong>. We had<br />

m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong>juries that required basic first aid, such as stubbed toes, and on two occasions<br />

members of the team had difficulty keep<strong>in</strong>g small wounds clean. Insect bites were a<br />

problem, but we were well-equipped with repellents, nets, and aftercare.<br />

23

One of us was almost mugged <strong>in</strong> the Old Taxi Park <strong>in</strong> broad daylight, although slightly<br />

shaken, no <strong>in</strong>jury was caused and stolen items were retrieved.<br />

Presentations and other Outputs<br />

- Q and A with Sussex Geography students also apply<strong>in</strong>g for field work grants<br />

- Presentation of f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs to Sussex Geography Society<br />

- Due to the closure of Makerere University due to the strikes, we were unable to<br />

present fully our key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs to students and Staff as our research sem<strong>in</strong>ar had<br />

to be cancelled<br />

- Dissem<strong>in</strong>ation of field work report to gatekeeper and <strong>in</strong>terested participants<br />

- Produced three <strong>in</strong>dependent geography undergraduate theses<br />

Experiences and the dissertations produced as a result will rema<strong>in</strong> as evidence of<br />

analytical and research skills developed throughout the process.<br />

This was a very challeng<strong>in</strong>g fieldwork trip; we had to overcome a number of difficulties<br />

and obstacles. Nonetheless, it proved a brilliant experience, made possible by the<br />

support we received from our University and the RGS. We are look<strong>in</strong>g forward to<br />

conduct<strong>in</strong>g further research <strong>in</strong> the future and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>ks <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kampala</strong>.<br />

Our time <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> was <strong>in</strong>valuable, and thoroughly enjoyable; it has given us great<br />

confidence and a chance to develop new skills and a thirst to cont<strong>in</strong>ue an academic<br />

career <strong>in</strong> geography.<br />

24

Bibliography<br />

Barnes, R and Eicher, J, 1992. Dress and Gender: Mak<strong>in</strong>g Mean<strong>in</strong>g. Berg: New York.<br />

Butler, J, 1990. Gender Trouble. Routledge: London.<br />

Callard, F, 2004. ‘Doreen Massey’. In Hubbard, P, Kitch<strong>in</strong>, R and Valent<strong>in</strong>e, G, 2004. Key<br />

Th<strong>in</strong>kers on Space and Place. SAGE: London, 219-225.<br />

Chapman, D., Burton, L. and Werner, J. (2010) ‘Universal secondary education <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Uganda</strong>: The head teachers’ dilemma’, International Journal of Educational Development.<br />

30 pp.77–82<br />

Del Cas<strong>in</strong>o, V. (2009) Social Geography. Wiley-Blackwell<br />

Dunne, M. (2007) ‘Gender, sexuality and school<strong>in</strong>g: Everyday life <strong>in</strong> junior secondary<br />

schools <strong>in</strong> Botswana and Ghana’, Internation Journal of Educational Development. 27(5)<br />

pp.499-511<br />

Dunne, M., Humpreys, S. and Leach, F. (2006) ‘Gender violence <strong>in</strong> schools <strong>in</strong> the<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g world’, Gender and Education, 18(1) pp.75-98<br />

Dwyer, C, 2008. ‘The Geographies of Veil<strong>in</strong>g: Muslim Women <strong>in</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong>’. Geography.<br />

93(3): 140-147.<br />

Ga<strong>in</strong>e, C. and George, R. (1999) Gender, ‘Race’ and Class <strong>in</strong> School<strong>in</strong>g: A New Introduction.<br />

London: RoutledgeFalmer<br />

Goetz, A-M. (1997) Gett<strong>in</strong>g Institutions Right for Women <strong>in</strong> Development. London: Zed<br />

Books<br />

Hall, S, 1992. ‘The Question of Cultural Identity’. In Hall, S, Held, D, and McGrew, T, 1992.<br />

Modernity and its Futures. Polity Press: Cambridge, 273-326.<br />

Hall, S. (1996) ‘Introduction: Who needs identity?’, <strong>in</strong> S. Hall and P. Du Gay (eds)<br />

Questions of Cultural Identity, London: Sage<br />

Harrison, M. (2006) ‘Collect<strong>in</strong>g Sensitive and Contentious Information’ <strong>in</strong> V. Desai and R.<br />

Potter (eds.) Do<strong>in</strong>g Development Research. London: Sage<br />

Holloway, L. and Hubbard, P. (2001) People and place: the extraord<strong>in</strong>ary geographies of<br />

everyday life. England: Pearson Education Limited<br />

Holt, L. (2004) ‘Children with m<strong>in</strong>d–body differences: perform<strong>in</strong>g disability <strong>in</strong> primary<br />

school classrooms’, Children's Geographies, 2(2) pp.219-36<br />

Jones, S. (2011) ‘Girls secondary education <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>: assess<strong>in</strong>g policy with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

women’s empowerment framework’, Gender and Education. 23(4) pp.385-413<br />

25

Kane, E. (1995)See<strong>in</strong>g for Yourself: Research Handbook for Girls’ Education <strong>in</strong> Africa.<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton: The World Bank<br />

Kitch<strong>in</strong>, R, and Tate, N (eds), 2000. Conduct<strong>in</strong>g Research <strong>in</strong>to Human Geography: Theory,<br />

Methodology and Practice. London: Prentice Hall.<br />

Little, J. (2002) Gender and Rural Geography: Identity, Sexuality and Power <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Countryside. England: Pearson Education Limited<br />

Longhurst, R, 1995. ‘The Body and Geography’. Gender, Place and Culture. 2(1): 97-105.<br />

Longhurst, R, 1995. ‘The Body and Geography’. Gender, Place and Culture. 2(1): 97-105.<br />

Mirembe, R. and Davies, L. (2001) “Is School<strong>in</strong>g a Risk? Gender, Power Relations, and<br />

School Culture <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>”, Gender and Education 13(4) pp.401-416<br />

Molyneaux, K. (2011) ‘<strong>Uganda</strong>’s Universal Secondary Education Policy and its effect on<br />

‘Empowered’ Women: How reduced <strong>in</strong>come and moonlight<strong>in</strong>g activities differentially<br />

impact male and female teachers’, Research <strong>in</strong> Comparative and International Education.<br />

6(1) pp.62-78<br />

Momsen, J. (2006) ‘Women, Men and Fieldwork: Gender Relations and Power<br />

Structures’, V. Desai and R. Potter (eds.) Do<strong>in</strong>g Development Research. London: Sage<br />

Muhanguzi, F. (2011) “Gender and Sexual Vulnerability of Young Women <strong>in</strong> Africa:<br />

experiences of young girls <strong>in</strong> secondary schools <strong>in</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>”, Culture, Health & Sexuality:<br />

An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care. 13(6) pp.713-725<br />

Paechter, C. (1998) Educat<strong>in</strong>g the Other: Gender, Power and School<strong>in</strong>g. RoutledgeFalmer<br />

Pa<strong>in</strong>, R, 2001. ‘Age, Generation and the Lifecourse’. In Barke, M, Pa<strong>in</strong>, R, Gough, J, Fuller,<br />

D, MacFarlane, R and Mowl, G, 2001. Introduc<strong>in</strong>g Social Geographies. Arnold: London,<br />

141-163.<br />

Perks, R, and Thomson, A (eds), 1998. The Oral History Reader. Routledge: London.<br />

UN (2009) United Nations Development Assistance Framework for <strong>Uganda</strong>, 2010-2014.<br />

<strong>Kampala</strong>: UN<br />

Valent<strong>in</strong>e, G, 2007. Theoris<strong>in</strong>g and Research<strong>in</strong>g Intersectionality: A Challenge for<br />

Fem<strong>in</strong>ist Geography. Professional Geographer. 59: 10-21.<br />

Valent<strong>in</strong>e, G. (2001) Social Geographies; Space and Society. London: Pearson Education<br />

Limited<br />

Van Blerk, L. (2006) ‘Work<strong>in</strong>g with Children <strong>in</strong> Development’, <strong>in</strong> Desai, V. and Potter, R.<br />

(eds.) Do<strong>in</strong>g Development Research. London: Sage<br />

26

Van Donge, J. (2006) ‘Ethnography and Participant Observation’, <strong>in</strong> Desai, V. and Potter,<br />

R. (eds.) Do<strong>in</strong>g Development Research. London: Sage<br />

World Bank (2012) World Development Indicators and Global Development F<strong>in</strong>ance.<br />

Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data (accessed 02/04/2012)<br />

27

APPENDIX 1:<br />

28