Kolokuma ideophones.pdf - Roger Blench

Kolokuma ideophones.pdf - Roger Blench

Kolokuma ideophones.pdf - Roger Blench

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Blench</strong> Izọn templatic <strong>ideophones</strong> Circulated for comment<br />

teuu not too high or low; average<br />

tẹụụ low, esp. of roof of house (pejorative sense)<br />

The application of ATR vowel quality to size usually applies to <strong>ideophones</strong> and it is rare to find examples in<br />

other parts of speech. However, this is not uncommon across the Njọ languages.<br />

3.3 Vowel height<br />

Westermann (1927, 1937) may have been the first author to point out the relations between vowel height and<br />

semantics in West African languages. The exact relationship between the quality of the sound and the vowel<br />

used to signify it is opaque and there do not appear to be regular correspondences across languages. Diffloth<br />

(1994) argues that individual languages may have systematic sound symbolism applied to <strong>ideophones</strong> but<br />

that such relationships cannot be generalised across languages. Nuckolls’ (1996) describes similar<br />

correlations between vowels and inside/outside distinctions in Pastaza Quechua. Nonetheless, there is<br />

apparently a widespread correlation between vowel height and size or depth in West Africa, which<br />

resembles the Austroasiatic examples. Oroko, a Bantu language in Southern Cameroun shows this<br />

relationship.<br />

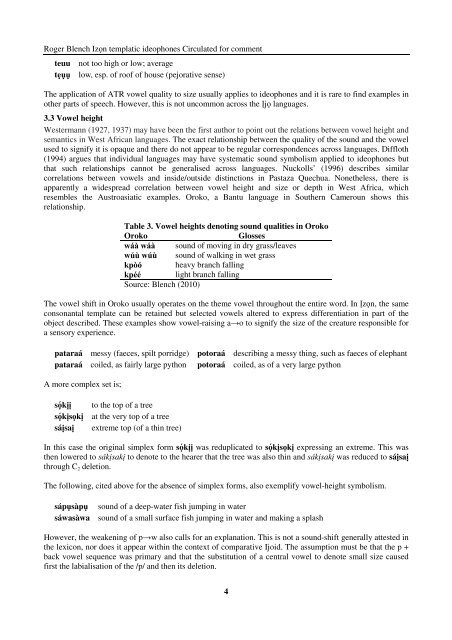

Table 3. Vowel heights denoting sound qualities in Oroko<br />

Oroko<br />

Glosses<br />

wáà wáà sound of moving in dry grass/leaves<br />

wúù wúù sound of walking in wet grass<br />

kpòó heavy branch falling<br />

kpéé light branch falling<br />

Source: <strong>Blench</strong> (2010)<br />

The vowel shift in Oroko usually operates on the theme vowel throughout the entire word. In Nzọn, the same<br />

consonantal template can be retained but selected vowels altered to express differentiation in part of the<br />

object described. These examples show vowel-raising a→o to signify the size of the creature responsible for<br />

a sensory experience.<br />

pataraá messy (faeces, spilt porridge) potoraá describing a messy thing, such as faeces of elephant<br />

pataraá coiled, as fairly large python potoraá coiled, as of a very large python<br />

A more complex set is;<br />

sọ́ kịị to the top of a tree<br />

sọ́ kịsọkị at the very top of a tree<br />

sáịsaị extreme top (of a thin tree)<br />

In this case the original simplex form sọ́ kịị was reduplicated to sọ́ kịsọkị expressing an extreme. This was<br />

then lowered to sákịsakị to denote to the hearer that the tree was also thin and sákịsakị was reduced to sáịsaị<br />

through C 2 deletion.<br />

The following, cited above for the absence of simplex forms, also exemplify vowel-height symbolism.<br />

sápụsàpụ sound of a deep-water fish jumping in water<br />

sáwasàwa sound of a small surface fish jumping in water and making a splash<br />

However, the weakening of p→w also calls for an explanation. This is not a sound-shift generally attested in<br />

the lexicon, nor does it appear within the context of comparative Ijoid. The assumption must be that the p +<br />

back vowel sequence was primary and that the substitution of a central vowel to denote small size caused<br />

first the labialisation of the /p/ and then its deletion.<br />

4