Moor Culinary habits - Sailan Muslim

Moor Culinary habits - Sailan Muslim

Moor Culinary habits - Sailan Muslim

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

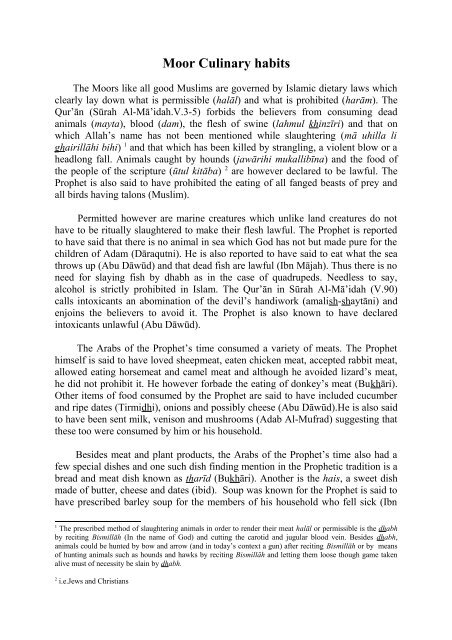

<strong>Moor</strong> <strong>Culinary</strong> <strong>habits</strong><br />

The <strong>Moor</strong>s like all good <strong>Muslim</strong>s are governed by Islamic dietary laws which<br />

clearly lay down what is permissible (halāl) and what is prohibited (harām). The<br />

Qur’ān (Sūrah Al-Mā’idah.V.3-5) forbids the believers from consuming dead<br />

animals (mayta), blood (dam), the flesh of swine (lahmul khinzīri) and that on<br />

which Allah’s name has not been mentioned while slaughtering (mā uhilla li<br />

ghairillāhi bihi) 1 and that which has been killed by strangling, a violent blow or a<br />

headlong fall. Animals caught by hounds (jawārihi mukallibīna) and the food of<br />

the people of the scripture (ūtul kitāba) 2 are however declared to be lawful. The<br />

Prophet is also said to have prohibited the eating of all fanged beasts of prey and<br />

all birds having talons (<strong>Muslim</strong>).<br />

Permitted however are marine creatures which unlike land creatures do not<br />

have to be ritually slaughtered to make their flesh lawful. The Prophet is reported<br />

to have said that there is no animal in sea which God has not but made pure for the<br />

children of Adam (Dāraqutni). He is also reported to have said to eat what the sea<br />

throws up (Abu Dāwūd) and that dead fish are lawful (Ibn Mājah). Thus there is no<br />

need for slaying fish by dhabh as in the case of quadrupeds. Needless to say,<br />

alcohol is strictly prohibited in Islam. The Qur’ān in Sūrah Al-Mā’idah (V.90)<br />

calls intoxicants an abomination of the devil’s handiwork (amalish-shaytāni) and<br />

enjoins the believers to avoid it. The Prophet is also known to have declared<br />

intoxicants unlawful (Abu Dāwūd).<br />

The Arabs of the Prophet’s time consumed a variety of meats. The Prophet<br />

himself is said to have loved sheepmeat, eaten chicken meat, accepted rabbit meat,<br />

allowed eating horsemeat and camel meat and although he avoided lizard’s meat,<br />

he did not prohibit it. He however forbade the eating of donkey’s meat (Bukhāri).<br />

Other items of food consumed by the Prophet are said to have included cucumber<br />

and ripe dates (Tirmidhi), onions and possibly cheese (Abu Dāwūd).He is also said<br />

to have been sent milk, venison and mushrooms (Adab Al-Mufrad) suggesting that<br />

these too were consumed by him or his household.<br />

Besides meat and plant products, the Arabs of the Prophet’s time also had a<br />

few special dishes and one such dish finding mention in the Prophetic tradition is a<br />

bread and meat dish known as tharīd (Bukhāri). Another is the hais, a sweet dish<br />

made of butter, cheese and dates (ibid). Soup was known for the Prophet is said to<br />

have prescribed barley soup for the members of his household who fell sick (Ibn<br />

1<br />

The prescribed method of slaughtering animals in order to render their meat halāl or permissible is the dhabh<br />

by reciting Bismillāh (In the name of God) and cutting the carotid and jugular blood vein. Besides dhabh,<br />

animals could be hunted by bow and arrow (and in today’s context a gun) after reciting Bismillāh or by means<br />

of hunting animals such as hounds and hawks by reciting Bismillāh and letting them loose though game taken<br />

alive must of necessity be slain by dhabh.<br />

2<br />

i.e.Jews and Christians

Mājah) and among the sweet foods he is said to have loved sweetmeats (halwa)<br />

and honey (asal) (Bukhāri).<br />

<strong>Moor</strong>ish fare<br />

The earliest accounts we have of <strong>Moor</strong> culinary fare date only from the 19 th<br />

century and we can only conjecture what their fare would have been prior to this<br />

period. Rice, the staple of the country, as well as flesh such as that of fowl would<br />

have probably constituted an important part of their diet. Dates and a few<br />

sweetmeats too may have been known.<br />

Simon Casie Chitty 3 provides us an insight into early 19 th century <strong>Moor</strong>ish fare<br />

when he mentions rice puddings, gruel and bruised plantains and milk figuring in<br />

ceremonies connected with a boy’s circumcision while Ahmadu Bawa 4 refers to<br />

ghee-rice with fried fowl, mutton curry, half a dozen vegetable curries and one or<br />

two pickles being served at the great feast at the bridegroom’s house known as<br />

māppillai vīddu pakatchoru.<br />

<strong>Muslim</strong> Cookery by Seniya Noordeen (1958) lists over fifty <strong>Moor</strong>ish dishes,<br />

some of which are not made so frequently as they used to be and some of which<br />

appear to have died out. The work has fortunately preserved for us an account of<br />

typically <strong>Moor</strong>ish dishes and beverages as they used to be prepared in the olden<br />

days, especially among the upper and middle classes. This includes rice dishes<br />

such as chicken buriyani and dhal pilau, meat preparations such as beef embul and<br />

chicken mosom, curry varities such as kaliya and thawttel, pickles such as salted<br />

billing and mango, sweet dishes such as sanja, firiny and wattilappam, sweet drinks<br />

such as faalootha, almond sherbet and gehwa and other food items such as Ellisha,<br />

Al Basra, Russian kalawan, semolina fritters and adukku rotti. Indeed, it is thought<br />

here worthwhile to give a brief description of the lesser known items mentioned by<br />

Noordeen some of which are no longer prepared.<br />

The rice meals given by her include kettu choru or picnic rice customarily<br />

served in <strong>Muslim</strong> homes on Odukkathu Puzan day (Ash Wednesday). She gives<br />

rice, chicken mosom, beef embul, kaliya, coconut mellun, potato curry, salted fish<br />

curry, fish roast, prawn curry, fried eggs, fried bombili, fried fish, fried beef, fried<br />

sweet potato and fried jak seeds as constituting the menu. Gotu buth, she gives as a<br />

menu consisting of rice, beef curry, thawttel, jak mellun and chutney, all served in<br />

a basket-like receptacle known among the Sinhalese as gotu and woven out of<br />

coconut leaves. The gotu, she says, is rectangular in shape and just large enough to<br />

hold rice and curry for one person. Dhal pilau she gives as a meal made with rice,<br />

3<br />

The Ceylon Gazetteer (1834)<br />

4<br />

The Marriage Customs of the <strong>Moor</strong>s of Ceylon JRAS.CB (1888)

dhal, Bombay onions, red onions and various spices, cooked in ghee and coconut<br />

milk.<br />

Noordeen also gives a variety of curries prepared by the <strong>Muslim</strong>s of her day.<br />

This includes thawttel, a curry made with pumpkin, breadfruit, plantains, sweet<br />

potato, red onions and maldive fish. Other curries given by her include beef embul<br />

(beef cooked in tamarind and other spices to make a thick curry) and chicken<br />

mosom (chicken heavily spiced with Bombay onions, green chillies, tomato and<br />

tamarind, fried and cooked to make a thick curry). Among the other items given by<br />

her, we may mention Al-Basra (a meal comprising of several layers of pancakes<br />

between which are placed a chicken mixture consisting of shredded chicken,<br />

onions and spices) and Ellisha (meal made of wheat paste, shredded mutton and<br />

red onions cooked in ghee).<br />

We will now deal with the contemporary fare of the <strong>Moor</strong>s, including the<br />

dishes peculiar to them. The staple fare of the <strong>Moor</strong>s like that of the Sinhalese and<br />

Tamils is rice 5 , which is consumed with a number of curries or side dishes. Meat,<br />

and especially beef and chicken figures prominently in the <strong>Moor</strong>ish diet. The<br />

traditional <strong>Moor</strong>ish dishes which we give below largely figure on special and<br />

festive occasions. A favourite rice dish which figures prominently in <strong>Moor</strong>ish<br />

feasts is the buriyāni, a rich and delectable dish that has its origins in Moghul<br />

India. The term itself is of Indian origin and seems to have derived from the<br />

Hindustani biryāni 6 .<br />

Buriyāni is usually made with fragrant bāsmati or sūduru sambā rice cooked in<br />

ghee with meat (usually beef or chicken) and potatoes, spiced with various<br />

condiments, scented with rose water and coloured yellow with colouring. It may<br />

also be embellished with green peas, cashew nuts and raisins. Accompaniments or<br />

side dishes include roasted chicken or chicken curry, an assorted curry made of<br />

liver, carrot, peas and cashew nuts, a date and onion pickle known as accār and a<br />

mint sambol made of mint leaves, green chillies, scraped coconut, garlic and<br />

ginger, all ground together to form a thick paste known as puduna sambal. Also<br />

commonly consumed with the buriyāni are slices of pineapple which gives zest<br />

and helps in the digestion of this heavy meal. The buriyāni served at important<br />

5<br />

The eating of rice as a popular dish among the <strong>Moor</strong>s has no doubt been influenced by the South Asian<br />

tradition and is a departure from the custom of the Arabs amongst whom the usual meal even in mediaeval<br />

times consisted largely of bread and meat (Mez.1922). Indeed, as evident in the Alf Layla Wa Layla or the<br />

Arabian Nights which reflects mediaeval Arabian society, it would appear that rice was more often than not<br />

regarded as a sort of luxury. The Arabic term for rice aruzz itself appears to be of Indian origin (Cf.T.arici<br />

‘rice deprived of husk’ though this term itself seems to have evolved from the Proto-Aryan * vrizhi.<br />

Cf.Skt.vrihi, Pers.birinc and Nuristani wric).<br />

6<br />

The dish is evidently an old one, for Abul Fazl in his 16 th century treatise on Moghul polity, Āin-I-Akbari<br />

gives biryān as a meat dish made from sheep with ghi and spices such as saffron, pepper and cuminseed. He<br />

also mentions a rice dish known as Duzdbiryān made of rice, meat and ghi. The term biryān from which<br />

biryāni evidently derives is a Persian loan in Hindustani literally meaning ‘fried, roasted, broiled, parched,<br />

grilled’.

functions such as weddings are generally partaken from a sahan or savan, a large<br />

metal platter, by a group of six seated around it 7 .<br />

The dish appears to be a relatively recent introduction from the subcontinent.<br />

Chitty (1834) nor Bawa (1888) mention it. Bawa also refers to ghee-rice with fried<br />

fowl etc figuring in a marital feast instead of buriyāni suggesting that it was<br />

probably not known among the <strong>Moor</strong>s of his time. Nevertheless Elsie Cook 8<br />

notices the dish figuring among the <strong>Moor</strong>s a few decades later. She says “ Their<br />

mode of cooking rice, with sultanas and fat, making a dish called burriana, has<br />

become characteristic in Ceylon”. In an earlier notice, an advertisement placed by<br />

Kamal Pasha Hotel of Maradana in 1923 9 we read of ‘buriyani rice’ and ‘fried<br />

fowls’ being offered by the hotel, suggesting that the dish would have been<br />

introduced from India for commercial purposes and that it was only later that it<br />

gained currency as a domestic dish.<br />

We were however informed by elderly folk that in the olden days, until about<br />

the 1930s or thereabouts, it was not buriyāni that was the common festive meal,<br />

but rather what was known as kalivirundu śōru, a rice dish prepared with ghee and<br />

various condiments such as cinnamon and embellished with pieces of pineapple,<br />

cashewnuts and raisins. Side dishes included potato, mutton curry, kaliya, fried<br />

beef or chicken and accār or a chutney known as bulaccan prepared with tamarind,<br />

chillie, sugar, vinegar and onions tempered in ghee. The term kalivirundu śōru<br />

used to denote this rice dish appears to derive from the Tamil kali ‘joy, mirth,<br />

delight’ and virundu ‘feast, banquet’ which would suggest that the dish was only<br />

prepared on very special occasions. The dish is still prepared on certain occasions<br />

like weddings, particularly in the rural areas.<br />

Another common rice dish neisōru or ‘ghee rice’ is made with rice, ghee, red<br />

onions, garlic, ginger, cinnamon, cardamoms, screwpine leaves (Pandanus<br />

latifolia), curry leaves (Murraya koenigii) and coconut milk, all of which are<br />

cooked together to form a delectable rice meal. Its traditional accompaniment is<br />

māśi sambal, a blackish sambol prepared by frying separately in coconut oil red<br />

onions, maldive fish, green chillies, pandanus and curry leaves and adding to it<br />

powdered chilli, lime juice and salt before mixing it well 10 . Another notable rice<br />

dish is manjal sōru or ‘yellow rice’ prepared by boiling rice in coconut milk and<br />

7<br />

The practice seems to be Arabian in origin as is suggested by the terms savan and sahan which seem to have<br />

originated from the Arabic sahn ‘dish’. The custom of partaking of meals in this manner is very likely based<br />

on the practice of the Prophet and his companions who are known to have partaken of food from a common<br />

dish known as Al-gharra which sufficed for several persons (Abu Dāwūd)<br />

8<br />

A Geography of Ceylon (1931)<br />

9<br />

The Crescent. The monthly organ of Zahira College. Oct.1923<br />

10<br />

Nowadays however it is fairly common to prepare a sambol (also known as māśi sambal) made of onions,<br />

Maldive fish and red chilli which are all light fried together in coconut oil to form a golden- brownish sambol.<br />

The sambol takes its name from the māśi or maldive fish that figures prominently in it.

turmeric. It is commonly consumed with some meat and potato curry. Yet another<br />

well known rice meal is the kiḍu or kiḍuvu śōru, a rice menu traditionally<br />

comprising of cooked samba rice, a curry known as tōtal, beef curry, mango curry<br />

and shredded and cooked jakfruit prepared similarly to the kos mällum of the<br />

Sinhalese. Today however the rice, beef and mango curry which figures in any<br />

ordinary kiḍu is commonly supplemented with potato curry, dhal curry and kaliya<br />

while the tōtal and jakfruit may be omitted.. The distinguishing feature of this meal<br />

is that it is placed in woven coconut leaf receptacles from which it takes the name<br />

of kiḍuvu (fr.T.kiḍugu). It is no doubt identical with the ‘Gotu-buth’ (A Sinhala<br />

term meaning ‘receptacle-rice) mentioned by Noordeen (1958). It is commonly<br />

consumed during the Ramaḍān period after the breaking of the fast and often<br />

distributed at kandūris held at the shrines of <strong>Muslim</strong> saints.<br />

Another rice meal, kettu sōru especially prepared by Galle folk consists of rice,<br />

dhal, kaliya, potato curry, karavāḍa poricci (fried dry-salted fish), pilākoṭṭa poricci<br />

(fried jak seeds), batala poricci (fried sweet potato), eracci poricci (fried beef),<br />

eracci mānga (mango chutney), mīn tīcci (fish cooked to a thick gravy), , amuku<br />

muṭṭa (boiled and fried egg), pilāka śundal (shredded and cooked jakfruit) and<br />

tēnga śundal (a yellowish grated coconut and turmeric sambol). This rice meal is<br />

packed in a packing made of plantain leaf, hence the name of kettu or ‘packeted’<br />

given to it.<br />

Pāl sōru (also known as pāl cōru or pāṭcōru) which literally means ‘milk rice’<br />

is similar to the kiribat of the Sinhalese and pukkai of the Tamils and is prepared<br />

by cooking rice in coconut milk, which when left to cool forms into a cake of firm<br />

consistency which is then cut into square- or diamond-shaped pieces. It is usually<br />

consumed at feasts given when a girl attains age or the day before the wedding.<br />

There is also paruppu cōru known in the south which is prepared by boiling rice<br />

and dhal in coconut milk.<br />

Eastern <strong>Moor</strong> folk such as those of Batticaloa also consume what is known as<br />

tanni sōru or tanni cōru where the rice cooked in the pot is mixed with water and<br />

left overnight before being mixed with red onions and green chillies and consumed<br />

the following morning. Karacci sōru is similarly prepared save that instead of<br />

onions and chillies, curd or coconut milk and some fruit such as banana or<br />

woodapple are added to it. Such karacci sōru is often consumed for breakfast and<br />

makes an invigorating meal. The <strong>Moor</strong>s of Jaffna also had what was known as<br />

tēngā cōru or tēngā sōru, a rice meal prepared with a copious quantity of coconut<br />

milk. It was consumed at festive occasions such as weddings, maulūds, kattams<br />

and other functions along with āṭṭarecci or mutton curry, a composite curry known<br />

as kāikari made by cooking together brinjals and ash plantains and a soup known<br />

as milahu-tanni prepared with garlic, turmeric, pepper etc. This meal is said to be<br />

still prepared by Jaffna <strong>Moor</strong>s domiciled in other areas, though not as frequently.

Among the popular side dishes served with the main rice meals we may<br />

mention the kuruma curries, chicken and beef kuruma which seem to have been<br />

influenced by the Hindustani qorma, a spiced fried curry. The curry which is<br />

characterized by an exotic aroma and gravy of a beige-brown hue is prepared by<br />

marinating the meat with a combination of spices such as chillie, pepper, turmeric,<br />

ginger, ground garlic, minced onions, coriander powder, cumin seed and tomatoes,<br />

all of which are put into tempered onions and cooked until it forms a thick gravy.<br />

Among the meat dishes, eracci ānam or beef curry cooked to a reddish brown<br />

with chillie and a variety of other condiments figures prominently. So does chicken<br />

curry (kōli ānam). Also popular, but less commonly consumed is mutton curry<br />

(āttarecci) prepared by cooking mutton in coconut milk, curd and various spices<br />

such as garlic, ginger and chilli. It is said that the <strong>Moor</strong>s of Jaffna hardly if ever<br />

consumed beef, very likely a result of the Hindu influence of the neighbouring<br />

Tamils, and that the meat of their choice was mutton. One also finds the flesh of<br />

the land monitor lizard (uḍumbu eracci) being consumed as a curry in certain parts<br />

of the country as in the Matara District. Some Batticaloa people are also known to<br />

be fond of this flesh, particularly of the type known as vella uḍumbu found in the<br />

paddy fields of that region.<br />

One also finds a variety of seafood being indulged in by the <strong>Moor</strong>s, especially<br />

those resident in the coastal districts, particularly fish (mīn) and prawns (rāl).<br />

Crabs (nandu) and bivalve molluscs (maṭṭi) are also consumed, but rarely 11 .<br />

Although Islam clearly permits seafood, some doubt has been expressed with<br />

regard to the permissibility of crustaceans like crab and sea reptiles like turtle 12 .<br />

Nevertheless, seafood is freely indulged in by the <strong>Moor</strong>s and even dugongs seem<br />

to have been once consumed with relish 13 .<br />

11<br />

P.E.P.Deraniyagala (Cured Marine Products of Ceylon. CJS.Sep.1933) mentions <strong>Moor</strong>s being among the<br />

chief consumers of maṭṭi, mussels of the Meretrix, Tapes, Venus and Donax gathered off the fringing coral<br />

reef of the west coast fishing villages. Even today one finds some <strong>Moor</strong>s of the southern and western coastal<br />

and estuarine areas consuming molluscs known as maṭṭi with relish. We were also told that the <strong>Moor</strong>s of<br />

Jaffna widely consumed such molluscs which were boiled in their shells before being removed and cooked<br />

into a devilled curry with a good quantity of chilli and other spices.<br />

12<br />

For instance, the Fathud-Dayyan though permitting eel, shrimp prawn, ray fish and cuttle fish, declares crab<br />

and tortoise to be harām. The prohibition of crab is perhaps based on an analogical deduction derived from<br />

the prohibition of birds having talons, the talons of birds of prey being likened to the claws of crabs. The<br />

prohibition of tortoise (including turtle etc) is somewhat more difficult to explain. There exists a common<br />

local belief that crab is makruh or disapproved and that consuming it continuously for a period of 40 days is<br />

forbidden though there does not appear to be any religious basis for this belief.<br />

13<br />

R.H.Bassett (Romantic Ceylon 1929) refers to dugongs caught off the seas of Jaffna and worth up to sixty<br />

rupees in the fish market, where the <strong>Moor</strong>men rush for it, while Christine Jonklaas (The Fishers of Portugal<br />

Bay.Loris.June 1937) refers to dugongs prized for their flesh by the <strong>Moor</strong>s of Puttalam and thereabouts. This<br />

herbivorous sea mammal known by the <strong>Moor</strong>s as āvūliyā in contrast to the proper Tamil term kaḍal-panḍri or<br />

‘sea-pig- has since undergone a dramatic decline in population, mainly it is said as a result of ‘overexploitation’.<br />

The dugong is said to have been common along the north-western coastal waters of Sri Lanka<br />

from the Puttalam lagoon in the south to the islands west of Jaffna in the north until the early part of the 20 th<br />

century. Indeed, dugongs were so plentiful in Sri Lanka that even as recently as the 1950s, some 100 to 150

Among the popular vegetable dishes may be included kaliya 14 prepared by<br />

cooking in coconut milk a mixture of fried brinjals and ash plantain cubes, liver,<br />

garlic, chillies and turmeric, though the liver may sometimes be omitted. There is<br />

also pacca kaliya where the ingredients are simply cooked in coconut milk. Potato<br />

curry (kelangu ānam) cooked in coconut milk and turmeric till a light yellow is<br />

also quite popular. Generally, however, the curry preparations of the <strong>Moor</strong>s are<br />

similar to those of the Sinhalese. For instance, vegetable curries like tender jak<br />

(polosikā), breadfruit (irapilāka), brinjals (kattirikkā) and pulses like dhal<br />

(paruppu). Other notable curries include irapilāka poriyal prepared by frying<br />

sliced breadfruit until a golden brown and cooking it in coconut milk and various<br />

condiments to form a thick curry. There is also pāl pilāka curry made with jakfruit<br />

bulbs cooked in coconut milk, onions, garlic and spices such as curry leaves,<br />

chillies and turmeric.<br />

Besides these, various dishes made of shredded vegetables or herbs mixed with<br />

grated coconut, onions, chillies etc are commonly consumed and are generally<br />

known as śundal, though the proper Tamil term from which it derives cundal<br />

means ‘stewed food, commonly vegetable’ (Winslow 1862). Such śundals are<br />

often consumed with rice. Well known herbs include vallāri (Centella asiatica)<br />

and ponnaṅgani (Alternanthera sessilis).<br />

Other relishes include a reddish pickle known as accār made of red onions,<br />

dates, capsicum, chillie, mustard seed, salted lime 15 , salted mango 16 , sugar and<br />

vinegar and consumed along with main rice dishes like buriyāni 17 . There is also<br />

pacaḍi or māṅga pacaḍi 18 which is basically a sweet and sour mango dish made<br />

by boiling in water pieces of raw mango after which it together with coconut milk<br />

and chillie powder is added to a pan containing stir-fried red onions, green chillies,<br />

garlic, mustard, curry leaves and other condiments. The curry is cooked till it<br />

animals were annually taken in the Mannar District. Today however it is doubtful if even 100 animals survive in<br />

the north-western coastal waters of the island, though a few animals do get caught occasionally, such accidental<br />

catches being incidental to the main fishing efforts of individual fishermen (See The dugong in Sri Lanka.<br />

Charles Santiapillai. Sri Lanka Nature.Dec.1999).<br />

14<br />

A term which possibly has its origins in the Hindustani qaliya ‘boiled or fried meat with dressing’<br />

(Cf.Ar.qaliyya ‘fried’, ‘roasted’, Pers.qalya ‘fried’, ‘flesh-meat dressed with anything’).<br />

15<br />

Uppudēsika, prepared by cutting limes into quarters, filling the spaces with salt and drying it or storing it for<br />

a few months<br />

16<br />

Uppumānga, prepared by boiling raw mango in salt water and drying it in the sun with salt<br />

17<br />

The accār seems to have had its origins in the Hindustani acār or Persian āchār which besides the usual<br />

meaning of ‘pickle’ is said to particularly refer to ‘onions preserved in vinegar’ (See A Comprehensive<br />

Persian-English Dictionary.F.Steingass).<br />

18<br />

Winslow (1862) gives paccaṭi as ‘a kind of seasoning for food, like pickles’. It also gives māṅkāippaccaṭi as<br />

‘mango pickle’. It is therefore very likely that the dish is of Tamil origin.

thickens before sugar is added to it and it is cooked further. This thick yellowish<br />

curry is usually consumed with rice.<br />

Another important relish which figures prominently in <strong>Moor</strong>ish meals,<br />

especially in areas like Galle is eracci māṅga or mango chutney made by cooking<br />

together mango, mustard seed, chillie and jaggery or sugar. There is also māsi<br />

poricci or fried maldive fish made by frying pounded maldive fish with sliced<br />

Bombay onions, green chillies, pandanus and curry leaves and eriyal, a kind of<br />

chutney also well known in southern areas like Galle prepared by frying long beans<br />

in oil and adding to it a mixture of plantain-flower, hog plum, pineapple, salted<br />

mango, salted lime, salted biling 19 , dates, maldive fish, jaggery and sugar with a<br />

variety of spices such as chillie, pepper and turmeric and cooking the whole in<br />

coconut oil to form a dark brown colour.<br />

Indeed, one would find many such regional specialities. Food items peculiar to<br />

Galle and especially the Galle Fort area include aviyal, a rich curry made by<br />

cooking together salted fish bone, white rice, scraped coconut, breadfruit,<br />

pumpkin, spinach, the sweet potato known as batala 20 and another kind of yam<br />

known as gahala 21 with coconut milk, turmeric and chillie. This dish is usually<br />

consumed with rice, fish and herbs 22 .<br />

There is also tōtal, a variety of aviyal where maldive fish is used instead of<br />

salted fish bone while spinach is also omitted. This dish is usually consumed with<br />

beef and shredded and cooked jak (pilāka śundal). It is little doubt identical with<br />

Noordeen’s thawttel which she describes as a curry made with pumpkin,<br />

breadfruit, plantains, sweet potato, red onions and maldive fish. Other popular side<br />

dishes here include karavāḍa poricci (fried dry-salted fish), banḍakkā puli (boiled<br />

ladies fingers 23 with scraped coconut) and puli (a sort of sambol prepared with red<br />

onions, green chillies, lime and salt).<br />

In Puttalam, there exists a well-known seafood dish made of the fatty variety of<br />

ray (kolapu tirikka) or shark (venna surā). It involves extracting the fatty lumps<br />

found in the insides of these fish and heating it on a slow flame so that it melts to<br />

form an oil. Onions and curry leaves are heated together in this oil before the more<br />

fleshy parts of the fish, spiced with chilli and turmeric, are added and the whole<br />

cooked to form an oily, reddish curry. The dish is usually consumed for lunch<br />

19<br />

Averrhoea bilimbi<br />

20<br />

Edulis batatas<br />

21<br />

Calocasia antiquorum<br />

22<br />

Aviyal is evidently a Tamil dish, although it is possible that it has undergone some variation locally among<br />

the <strong>Moor</strong>s. Winslow (1862) gives aviyal as ‘boiled food’ or ‘a kind of curry without acid’<br />

23<br />

Hibiscus esculentus

along with rice and a soup known as puliyānam. This soup is prepared by boiling<br />

in water onions, green chillies, curry leaves, gamboge and cumin before adding to<br />

it the tail end and bony parts of the fish, whether shark or ray fish, after which<br />

thick coconut milk is added to form a rather nourishing relish to the main meal.<br />

Typical eastern fare includes kānja-eracci which is prepared by boiling meat,<br />

usually beef, in salt and turmeric and roasting it. This is said to have been formerly<br />

prepared by smoking the meat over a fireplace (aduppu) or wooden frame (paran).<br />

Such meat could be cooked as a curry, fried or made into a sambol by pounding it<br />

into little pieces. Also peculiar to the east is what is known as suṭṭa eracci where<br />

raw meat is placed on sticks and heated over an open fire much like the kabābs of<br />

the Arabs. It is usually consumed on occasions like the Hajj festival when meat is<br />

plentiful. Tēn eracci or ‘honey meat’ was also once widely known in the eastern<br />

districts such as Batticaloa at a time when there was plenty of game to be had. The<br />

game which comprised the flesh of wild animals such as deer (mān), marai<br />

(sambhur) and jungle hare (kāṭṭu musal) would be smoked over a fire before being<br />

dipped in bees’ honey and stored to be consumed at a later date. It was also made<br />

into a sambol-like dish by chopping it into fine pieces and mixing it with onions<br />

and chillies by which means it became a delicious relish to be consumed along<br />

with rice broth (arisi kanji).<br />

Eastern folk also commonly consume fried items simply known as poriyal such<br />

as little fried fish mixed with red onions and green chillies. They also commonly<br />

add seafood such as the little fish known as sūḍal, sprats, prawns or maldive fish to<br />

their vegetable curries. This is believed to enhance the taste of the curry. The eggs<br />

of the freshwater fish known as keluti is also much relished, being made into a<br />

tantalizing devilled dish with chilli and other spices.<br />

Other Eastern <strong>Moor</strong> specialities include uraippu kanavā curry and uraippu rāl<br />

curry, seafood dishes made of cuttle fish and prawn respectively. The cuttle fish or<br />

prawn as the case may be is fried in oil before being cooked in coconut milk and<br />

lightly fried onions, tomato and chillies. Furthermore beef curry is often cooked<br />

with manioc (maravalli kilaṅgu) which is said to make a most delicious dish. Some<br />

folk residing in the coastal areas of the Batticaloa District are also known to<br />

consume a strong intoxicating dish known as baṅgu prepared by cooking beef liver<br />

(māṭṭu īral) with cannabis leaves (kanjā ila) and other condiments.<br />

Besides the main dishes prepared with rice and the curries and other side dishes<br />

that go with it, we also find a number of other food items commonly consumed by<br />

the <strong>Moor</strong>s, especially on festive occasions. These include aḍukku roṭṭi 24 , a<br />

delectable baked dish made of several layers of pancakes interspersed with a<br />

mixture of minced beef, Bombay onions, garlic, green chillies and herbs such as<br />

24<br />

Aḍukku roṭṭi takes its name from its being piled one over another (T.aḍukku ‘pile’ or ‘to pile up one on top<br />

of another’)

celery, pandanus and curry leaves all cooked in oil, kunāfa 25 , a savoury cake<br />

comprising of several layers of shredded pancakes interspersed with minced beef<br />

filling and samosa, a triangular pastry filled with minced beef which seems to have<br />

originated in India where it is known by the same name among the Hindustanispeaking<br />

population of the north 26 .<br />

Other less ceremonial, more commonly consumed food items include appam or<br />

hoppers 27 , a crisp circular cake with a soft puffed spongy centre made of rice flour<br />

and coconut milk, roṭṭi 28 , a hard circular cake made of wheat flour and grated<br />

coconut and puṭṭu 29 , a cylindrical cake prepared by steaming in a special cylinderlike<br />

mould a mixture of rice flour and grated coconut. In the Eastern areas one<br />

would find a variety of this rice cake known as mani piṭṭu which is quite popular.<br />

This is prepared by steaming in a special bamboo or palm leaf container known as<br />

nīṭṭupeṭṭi a mixture of roasted rice flour, grated coconut and water, all formed into<br />

little pearl-shaped globules, hence the name of mani or ‘jewel’ given to it. The<br />

Eastern <strong>Moor</strong>s also commonly prepare what is known as pāl appam or ‘milk<br />

hoppers’ made by adding to the centre of the hopper thick coconut milk (talai pāl)<br />

while it is being prepared, thus giving the puffed centre a soft texture and a<br />

delicious creamy taste.<br />

Besides these, one would find iḍi-appam or string-hoppers 30 , stringy circular<br />

cakes formed by forcing fine strands of dough made of rice or wheat flour through<br />

a perforated mould, placing them on special circular mats and steaming them, and<br />

iḍiappam-buriyāni or string-hopper buriyāni which is made like rice buriyāni, save<br />

that stringhoppers are used instead of rice. Though one might be tempted to think<br />

of this as a recent introduction, this is not so, for Noordeen (1958) mentions it.<br />

25<br />

The dish is evidently of Arab origin, though surprisingly it seems to have originally been a sweet rather than<br />

savoury dish. In the story of Ma’aruf the Cobbler occurring in the Alf Layla Wa Layla we find kunāfah<br />

figuring as a sweet dish made of vermicelli cake, fried with clarified butter and sweetened with treacle or<br />

bees’ honey, while Lane says in his Modern Egyptians (1836) “A favourite sweet dish is koona’feh, which<br />

is made of wheat-flour, and resembles vermicelli, but is finer; it is boiled, and sweetened with sugar or<br />

honey”.<br />

26<br />

This item may however have an Arab or Persian origin (Cf.Ar.sanbūsak ‘triangular meat pie’, Pers.sambūsa<br />

‘kind of triangular pastry’)<br />

27<br />

This item is of South Indian origin, where appam means ‘round cake of rice flour and sugar fried in ghee’<br />

though it is possible that the term and the dish itself is of ancient North Indian origin, for it is not unlikely for<br />

the Tamil term appam to have derived from the Skt.apūpa ‘cake of flour, meal , & c’ which occurs in early<br />

Vedic literature such as the Rg Veda (See A Sanskrit-English Dictionary.Monier- Monier Williams.1899)<br />

28<br />

This item probably has its origins in the Hindustani roṭi ‘a bread-cake’<br />

29<br />

This meal is evidently of Tamil origin and derives from the T.piṭṭu, a term which appears to have its origins<br />

in Skt.piṣṭa ‘flour’. The meal is evidently an old one and is even known to the author of the Cilappatikāram<br />

who makes mention of sellers of piṭṭu.<br />

30<br />

Very likely from the Tamil .iḍiyappam, an identical meal. The term probably has its origins in the T.iḍ i<br />

‘ground grain’, ‘rice flour’ and appam ‘cake’

Stringhopper buriyani is also said to have been served on the occasion of a Macan<br />

Markar wedding on 9 th September 1944 at the height of World War II due to nonavailability<br />

of basmathi rice at the time 31 and it is possible that it in fact originated<br />

in the war years due to that very reason. Also prepared in the olden days though<br />

hardly if ever today was a rich meal known as halīśā made of wheat paste, meat<br />

and onions and cooked in ghee. It is little doubt identical with Noordeen’s Ellisha<br />

which she describes as being made of wheat paste, shredded mutton and red onions<br />

and cooked in ghee).<br />

There is also frāns āppa or ‘French hoppers’ made in areas such as Galle which<br />

is prepared by cooking together semolina, coconut milk, fried onions and shredded<br />

beef, after which it is poured on a tray, topped with beaten eggs and baked. It is<br />

usually consumed with some curry such as chicken curry. Among the notable<br />

eastern <strong>Moor</strong>ish dishes may be mentioned the uraippu aḍai, a sort of savoury cake<br />

made of roasted rice flour, fried prawns, eggs, onions and chillies, all baked in a<br />

clay pot. The <strong>Moor</strong>s of Jaffna also had what was known as pāl āḍai, a pancake<br />

made of a batter of rice flour, coconut milk and egg and commonly consumed with<br />

mutton curry.<br />

Indeed, many of these dishes have their accompaniments. Puṭṭu may be<br />

consumed with bābat (honey comb tripe) and kodal (bovine bowels) and appam<br />

and iḍi-appam with beef curry. Roṭṭi is also usually consumed with some curry<br />

such as beef curry or bananas. Similarly, iḍiappam buriyāni may be consumed<br />

with kīmā, a mixture of minced beef, Bombay onions, garlic, green chillies and<br />

herbs such as celery, pandanus and curry leaves, all of which are cooked in oil to<br />

form a delicious curry.<br />

Gruels and soups<br />

<strong>Moor</strong> folk also consume a considerable variety of gruels and soups. Among<br />

them we may mention kanji, a rejuvenating gruel made with rice, beef, fenugreek,<br />

ginger and garlic and cooked in coconut milk. This gruel is commonly prepared<br />

during the time of the Ramaḍān fast, not only in homes, but also in mosques where<br />

it is liberally dished out to all and sundry who happen to be there at the time of<br />

breaking the fast. That this was also the practice in the olden days is borne out by<br />

Shamsiden (1886) who alludes to the <strong>Moor</strong>s, both rice and poor, drinking each a<br />

cupful of kanji at the time of breaking the fast 32 .<br />

31<br />

See Short Biographical Sketches of Macan Markar and Related Families. A.H.Macan Markar (1977)<br />

32<br />

An ancient Tamil work assigned to the early centuries of the Christian era, the Pattinap-palai refers to kanci<br />

filtered out of the rice cooked in feeding houses flowing in a stream and spreading over the land, which<br />

would imply that it originally meant the water left over after the cooking of the rice. The MTL (1926) gives<br />

kanci as ‘rice water’, ‘water in which rice has been boiled and which is drained off after the rice has been<br />

cooked’ as well as ‘liquid food’ and ‘gruel prepared from cereals’. It is quite possible that this kanji went<br />

through an intermediate stage where the water of boiled rice was left overnight and consumed the following

Another type of gruel, gōdamba kanji is made by boiling wheat and chicken in<br />

coconut milk 33 . There is also rulaṅ kanji, a thick gruel made of semolina, coconut<br />

milk, onions and some meat such as chicken, and sau kanji, a sweet brownish gruel<br />

made of sago, coconut milk, kitul jaggery and cinnamon. It is usually consumed<br />

with bananas 34 .<br />

The <strong>Moor</strong>s of Jaffna are known to have consumed a gruel known as pulikkanji<br />

prepared by boiling together red rice, coconut milk, tamarind juice, prawns and<br />

leaves such as muruṅgā (Moringa Oleifera) or kovvā (Cephalandra Indica) to<br />

which is sometimes added onions and green chillies. The <strong>Moor</strong>s of the Panadura<br />

area are also said to have formerly consumed a gruel known as poduval made of<br />

sago, cow’s milk, cashewnuts and raisins. Kiccaḍi, a mess of rice, green gram and<br />

jaggery cooked in coconut milk and spiced with cardamoms is also prepared in<br />

<strong>Moor</strong>ish homes and was known even in the olden days 35 .<br />

Among the traditional <strong>Moor</strong> soups may be mentioned puliyānam (lit.sour<br />

gravy) made with a variety of ingredients including onions, garlic, ginger, pepper,<br />

tamarind and cumin. In the Puttalam area the preparation of puliyānam differs from<br />

the rest of the island and is made by boiling in water onions, green chillies, curry<br />

leaves, gamboges and cumin before adding to it the tail and bony parts of some<br />

fish such as shark or rayfish. The molavutanni which is known as milahutanni<br />

(Fr.T.milagutanni or ‘pepper-water’) in the Eastern districts such as Amparai<br />

comprises of an invigorating soup made largely with garlic and pepper. It is often<br />

given to women recuperating from childbirth. The term molavutanni may however<br />

also be used to denote a soup made of beef or chicken. Another kind of soup<br />

especially known in the south is the puluppu made by boiling together tomato,<br />

Bombay onion, grated coconut, maldive fish, pepper and salt.<br />

Beverages<br />

day by adding other items which is exactly what kanji still denotes in the Lakshwadweep Islands<br />

33<br />

We find Godamboo kanji figuring in a mid-1930s <strong>Moor</strong> breakfast along with Alisha (Markar 1977)<br />

34<br />

Lionel Juriansz (Hungry ? A gastronomic voyage. The Times of Ceylon Christmas Number 1951) mentions<br />

sweetened sago porridge and ripe bananas figuring in the typical <strong>Moor</strong>ish breakfast, showing that it has been<br />

popular among the <strong>Moor</strong>s for a considerable time<br />

35<br />

The dish is very probably of Indian origin. Abul Fazl (16 th century) gives khichṛī as a dish made from rice,<br />

mūng dāl and ghī while still earlier, we have Ibn Battuta (14 th century) referring to munj, a kind of green grain<br />

being cooked along with rice and eaten with butter, a dish which he says they call kishrī. In modern industani,<br />

khichḍī denotes a mess of rice cooked with dal and ghee and flavoured with onions and spices.

By far the most popular beverage among the <strong>Moor</strong>s is fāluda 36 , a refreshing<br />

drink of a rosy hue made of milk and rose syrup and often embellished with kaḍalpāsi<br />

or agar agar (Seaweed moss jelly) and kasa kasā (black basil seeds which<br />

assume a soft, gelatinous, translucent coating when placed in water). It may also be<br />

embellished with ispagōl or psyllium (Fleawort seed) husks which is believed to<br />

have cooling and laxative properties and is especially consumed during the month<br />

of Ramadān. The rose syrup usually employed for the purpose is prepared by<br />

heating together essence of rose, sugar, water and red colouring so that it assumes<br />

a deep red colour and a consistency very much like treacle.<br />

Among the other well known beverages may be included saruvat 37 , a sherbet<br />

made with rose syrup though it may also denote a fruit juice made of the juice of<br />

citrus fruits such as lime or orange embellished with pieces of pineapple and kasa<br />

kasā. In the olden days however, saruvat is said to have been commonly made of<br />

lime, pineapple, sugar and water. There is also nannāri, a sherbet made with the<br />

extract of sarsaparilla (Hemidesmus indicus) and bādam made with the essence of<br />

almond and consumed with or without milk. Woodapple juice (bulāṅga pāl) made<br />

with the pulp of the ripe woodapple fruit (Limonia acidissima), coconut milk and<br />

jaggery or sugar is also consumed. There is also māṅga pāl which is similarly<br />

made save that mangoes are used instead of woodapple. Another drink consumed<br />

on special occasions is pāl palam (milk and bananas, also known as niyyatu pāl<br />

(intention milk). The drink which is made by boiling milk and adding to it slices of<br />

bananas is given to little children when one’s wishes such as a marriage or<br />

business deal has been realized.<br />

Another refreshing beverage, albeit a hot one, is kahuwa kōpi which is made<br />

with coffee, milk, cloves, cardamoms, cinnamon and dried ginger. This beverage is<br />

also known as śukku (lit.dry ginger) in southern regions such as Galle and<br />

36<br />

The beverage is very likely of Arabian, Persian or Indian origin. In Arabic fālūd or falūdaj means ‘a<br />

sweetmeat of flour, water and honey’ and probably derives from the Middle Persian pālūdag. In Persian<br />

pālūda refers to ‘a kind of sweet beverage made of water, flour and honey’. In Hindustani faluda refers to a<br />

drink or its main ingredient prepared from parched ground wheat as well as a kind of vermicelli. In North India,<br />

we often find the term being applied to the noodle-like vermicelli made of corn flour which is used as a garnish<br />

for that Indian ice cream known as kulfi which is often topped with rose-syrup though in Bombay and the<br />

regions around it faluda often refers to the drink. It is therefore possible that faluda originated from the kulfi<br />

topped with rose-syrup so well known in India and that it took its name from the sweet vermicelli added to it, an<br />

item which probably had its origins in the Arab fālūd.<br />

37<br />

The term saruvat is evidently of Arab origin, being derived from the Arabic sharbat meaning a drink or<br />

beverage. The final t is however generally silent in spoken Arabic so that we might have to suppose that the<br />

form saruvat has arisen through the medium of Persian or Hindustani where the final t has been retained.<br />

Although it might have ultimately had an Arab origin as suggested by the name and its occurrence in works<br />

such as the Alf Layla Wa Layla where we comes across references to rose sherbet as in the tale of King<br />

Umar Al-Numan, sugared sherbet scented with rose-water as in the tale of Khalifah and sherbet flavoured<br />

with rose- water, scented with musk and cooled with snow as in the tale of Nur Al-Din Ali and his son, it<br />

were the Turks who apparently popularised it. It originally seems to have denoted as fruit-based drink.<br />

Among theTurks, sherbet was made of the juice of lemons, water and sugar (The general history of the<br />

Turkes.Richard Knolles.1621). Sherbets were also made of roses, rhubarb and tamarinds (Narrative of<br />

travels in Europe, Asia and Africa.Ewliya Čelebi.Trans. J.Von Hammer.1834-1850)

Colombo, especially when taken without milk 38 . Coffee may also be consumed<br />

with milk and sugar while sometimes a mixture of raw egg, jaggery and<br />

cardamoms is added to it in which case it is known as muṭṭa kōpi or “egg coffee’.<br />

also with a raw egg mixed with it. There is also ganjakōpi or Ganja Coffee made<br />

by combining coffee with ganja or cannabis. It is said to be still consumed by the<br />

labouring community of the Eastern Province such as agricultural workers. Tea is<br />

also widely consumed either plain with sugar and ginger or with milk. Nannāri Tī<br />

prepared by adding to the tea a piece of sarsaparilla is known to be popular in the<br />

eastern districts such as Batticaloa.<br />

The <strong>Moor</strong>s of old are also known to have consumed an intoxicating beverage<br />

known as sabji. This beverage is said to have been common until about the 1970s<br />

when it gradually declined. John Attygalle 39 refers to sabji as being used largely<br />

by the ‘Mohammedans’. He gives it as a preparation made of ganja or cannabis<br />

powder, mixed with black pepper, cucumber, melon seeds and sugar, half a pint of<br />

milk and an equal quantity of water. The recipe however was not always the same<br />

for we were informed by several elderly folk of Gintota that the beverage was<br />

prepared with opium, cannabis, eggs, kitul jaggery, mashed banana of the kōlikuttu<br />

variety and a white form of poppy seed known as vella kasakasā. Dikwella in the<br />

south is said to have been well known for the beverage 40 . There can be no doubt<br />

that from a religious viewpoint, such intoxicating beverages are harām in keeping<br />

with the Qur’ānic injunction 5:90 and the Prophetic tradition (Abu Dāwūd) 41 .<br />

Desserts and Sweetmeats<br />

38<br />

The beverage is probably of Arab origin. The term kahuwa itself seems to have originated from the Arabic<br />

qahwa ‘coffee’. Noordeen (1958) gives the term gehwa for kahuwa kōpi. The tradition of adding condiments<br />

such as cardamom to coffee has very probably been influenced by Arab custom. The practice is alluded to<br />

by Lane (1836) who says that the Egyptians often add ‘cardamon-seed’ to their coffee. It is not unlikely that<br />

coffee has figured in the life of the <strong>Moor</strong>s as among their Arab brethren for quite some time. Coffee was known<br />

among the Arabs since at least the 15 th century, having had its origins in the Kaffa Province south of Abyssinia<br />

before being introduced to Mokha in Yemen C.1430 by Shaykh Al- Shazili whence it began to spread to other<br />

parts of the Arab world (See Burton 1964). Indeed, there are those like John Ferguson (Ceylon in 1883) who<br />

believe that it was the Arab traders who first introduced to the island the coffee plant.<br />

39<br />

Sinhalese Materia Medica (1917)<br />

40<br />

This sabji is evidently of Indian origin and appears to be identical with the sabzi of the Indians ‘an<br />

intoxicating potion made of bhang’ (Forbes 1857). Richard Burton in his translation of the Arabian Nights<br />

observes that sabzi is prepared with dried hemp leaves, poppy seed, cucumber seed, black pepper and<br />

cardamoms rubbed down in a mortar with a wooden pestle and made drinkable by adding milk.<br />

41<br />

Some have however sought to justify or permit the taking of narcotic substances in quantities that will not<br />

intoxicate. The Fathud-Dayyan for instance declares to be haram substances that cause injury to a person’s<br />

intelligence such as for instance toddy, arrack and other intoxicating drinks and when taken in larger<br />

quantities ganja, opium, nutmeg and its mace. It adds that a little opium or ganja may be added to medicines<br />

where necessary and that nutmeg and mace may be eaten in quantities that will not intoxicate.

Luncheons in the olden days are said to have been followed by a dessert known<br />

as pāl-cōru or ‘milk-rice’ which consisted of cooked rice in mashed plantain taken<br />

with sugar and curd or woodapple cream and jaggery. The dish probably survives<br />

in the kariyal or karacci soru of the Eastern <strong>Moor</strong>s. It is prepared by mixing rice<br />

together with curd, bananas and sugar or mixing the rice with coconut milk,<br />

woodapple juice and sugar. Chitty (1834) refers to the females of the family<br />

presenting to the bridegroom a cup of bruised plantains and milk (very much like<br />

strawberries and cream) when on his way to the home of the bride on the wedding<br />

day. The same is said to have been presented to the boy before he was circumcised.<br />

All this would suggest that this dish was well known among the <strong>Moor</strong>s of yore and<br />

was often consumed on ceremonial occasions.<br />

Among the desserts or sweet dishes commonly indulged by the <strong>Moor</strong>s of today,<br />

the vaṭṭalappam, a rich pudding made with eggs, coconut milk, jaggery and<br />

cardamoms, occupies the foremost place 42 . This soft brownish pudding is prepared<br />

by adding a mixture of heated jaggery, coconut milk and ground cardamoms to a<br />

stock of beaten eggs after which the whole is poured into bowls and steamed till it<br />

assumes a firm consistency. It is often served with bananas, usually of the kōlikuttu<br />

variety. Firiny which Noordeen (1958) says is made with milk, sugar, semolina and<br />

vermicelli, probably has its origins in the Hindustani firni, a sweet dish made of<br />

milk, sugar and ground rice. Today the term may also denote a semolina or milk or<br />

custard pudding embellished with cashewnuts and raisins and often served with<br />

bananas. Sanjā, a jelly made of seaweeds such as kaḍalpāsi also known as Jaffna<br />

or Ceylon moss (Gracilaria lichenoides) and agar agar or China moss ( Gelidium<br />

amansii) commonly found in the coastal areas of the Indian ocean is also well<br />

known. The jelly is formed by boiling the dried seaweed in water before adding<br />

sugar and some colouring (in case it has not been previously coloured) to it. Milk<br />

is also sometimes added to it 43 .<br />

Cakes are also known and a special kind of cake prepared by the <strong>Moor</strong>s is the<br />

bōl, a spongy cake made of rice flour, sugar, eggs and cardamoms, all baked to<br />

42<br />

Vaṭṭalappam is evidently a corruption of the T.vaṭṭil ‘cup’ + appam ‘cake’, hence vaṭṭilappam ‘cup-cake’.<br />

The dessert seems to have been formerly known as vla, evidently a Dutch loan. Louis Nell (An explanatory<br />

list of Dutch words adopted by the Sinhalese. The Orientalist.1888-89) notes that the Dutch term vla ‘a<br />

custard’ is applied by the <strong>Moor</strong>men to a custard which has a vernacular name in vattil-appan evidently of<br />

Tamil origin. The dish is however unknown to the Tamils.<br />

43<br />

The term sanja used for the jelly does not appear to have a Dravidian, Hindustani or Arabian origin.<br />

Deraniyagala (1933) alludes to Ceylon moss being called chan-chow parsi locally, a name which he believes<br />

to be of Chinese origin. He adds that it is to be obtained in the markets of most towns and that hawkers of<br />

cool drinks prepare a jelly from it known as chan-chow which sets without the aid of ice. It would appear that it<br />

is this chan-chow that eventually became our sanja. It is a well attested fact that the initial voiceless palatal c<br />

tends to undergo sibilization (become s) in the refined Tamil of the <strong>Moor</strong>s while the palatal c following a nasal<br />

is softened to j. Thus it is not unlikely that a term like chanchow could have become sanja with time. It is very<br />

likely that the term chanchow itself had its origins in the Chinese chin-chow or ‘grass jelly’ which is prepared<br />

very much like our sanja though it is often drunk as well.

form little bowl-shaped cakes 44 . Another kind of cake commonly made in the<br />

olden days, but hardly if at all today is the aḍa 45 , made of flour, eggs, coconut<br />

milk, sugar or jaggery, which are tempered in coconut milk, onions and ramba<br />

before baking it by heating it in a fire below and placing above it heated coconut<br />

shells. The <strong>Moor</strong>s of Jaffna are said to have made a similar cake known as aḍai<br />

with rice flour, egg and sugar and often embellished with cashewnuts or peanuts.<br />

Eastern folk are however still believed to make the inippu aḍai, a cake made of<br />

roasted rice flour, roasted green gram, dates, peanuts, eggs, sugar and coconut<br />

milk.<br />

A sweetmeat known as koḷukkaṭṭai is also still made in certain conservative<br />

areas like the Eastern Province. It is prepared by placing into the centre of a flat,<br />

circular shaped piece of dough made of rice flour, a mixture of roasted and<br />

coarsely pounded green gram, grated coconut, jaggery and cardamom powder<br />

before folding it into two so that the ends meet to form a semicircle after which the<br />

ends are pressed together to form a frilled pattern before it is steamed 46 .Paniyāram<br />

or oil cakes are prepared by frying a batter of flour, jaggery and coconut milk in<br />

coconut oil until a golden brown. It is identical with the paniyāram of the Tamils<br />

and kävum of the Sinhalese. The <strong>Moor</strong>s of the Eastern districts such as Batticaloa<br />

also prepare what is known as kaivicci paniyāram, an oil cake made by mixing the<br />

treacle-like juice obtained by placing marudam (Terminalia glabra) leaves in<br />

water, with flour and sugar and forming it into a dough which is taken by the hand<br />

and put into boiling coconut oil. Sugar syrup is thereafter added to it as a topping.<br />

The <strong>Moor</strong>s of Jaffna also had two more varieties, namely, the sittundi<br />

paniyaram prepared by frying a batter of rice or wheat flour, coconut milk and egg<br />

to form diamond-shaped cakes which were topped with heated sugar liquid<br />

resulting in a white crystalline surface, and the panangāi paniyāram prepared by<br />

mixing rice or wheat flour with the pulp of the palmyra fruit ( Borassus flabellifer)<br />

and sugar to form onion-shaped boluses which were then fried until a golden<br />

brown.<br />

Aliyataram is prepared by adding rice flour and course rice particles left over<br />

after pounding the rice into boiling treacle or sugar syrup to form a dough after<br />

which it is formed into little boluses and flattened before frying until a golden<br />

44<br />

The cake it is possible takes its name from the English term bowl whose shape it resembles or else is a<br />

corruption of bolo, a word evidently of Potuguese origin and denoting a kind of cake (See An explanatory list of<br />

Portuguese words adopted by the Sinhalese.Louis Nell. The Orientalist.1888-89).<br />

45<br />

Evidently a corruption of the T.aḍai meaning ‘cake or bread in general’<br />

46<br />

This sweetmeat is also known among the Tamils of the Northern and Eastern Provinces and appears to be<br />

Tamil in origin. In South India however the term kolukkaṭṭai denotes a ‘bolus like preparation of rice flour<br />

usually with coconut scrapings, sugar etc’ (MTL 1926).

own. Poravam is prepared by mixing together rice flour and green gram flour<br />

with ghee after which is it cut into squares and fried in ghee.<br />

Among the other well known sweetmeats may be included maskat, an oily<br />

sweetmeat made of wheat flour, ghee, sugar and cashewnuts and coloured green,<br />

red or yellow. It is usually characterized by a soft crust that forms on the sides of<br />

its outer surface 47 . Another well known muscat is that known as śavvarsi maskat<br />

made of sago, ghee, sugar and cashewnuts. It is known as śavanarśi maskat among<br />

Galle people. The <strong>Moor</strong>s of the Eastern areas like Nindavur also prepare a dark<br />

brownish muscat known as lodal by boiling together rice flour, coconut milk and<br />

sugar. The <strong>Moor</strong>s of Jaffna now dispersed to other areas prepared a similar muscat<br />

they called dodol made of rice flour, coconut milk and a course sugar known as<br />

sakkarai. These are very much similar to the dodol of the Malays and would have<br />

probably been borrowed from them. There is also jalabi, a golden-coloured, spiral,<br />

tubular sweetmeat made of a batter of wheat or rice flour, gram flour and curd fried<br />

in oil and soaked in a thick sugar syrup while still hot whereupon it absorbs the<br />

sugar which forms a sweet liquid inside while crystallizing on the surface. This<br />

delectable, crispy sweetmeat is often consumed during the Ramaḍān period 48 . It is<br />

commonly known as tēnkulal (lit.honey-tube) in the eastern districts where it is<br />

often coloured red.<br />

Also well known, especially in the urban areas like Colombo, are the gulāb<br />

jamun, spongy little brown croquettes made of milk, flour and margarine, fried in<br />

oil and soaked in a thick syrup made of sugar and rose essence 49 . Yet another<br />

delectable sweetmeat commonly prepared in <strong>Moor</strong>ish homes is ambarelikā dōsi<br />

made by boiling forked hog plum (Spondias mangifera) in a syrup of sugar, water<br />

and powdered cardamoms. Other similar confections include mānga dōsi made<br />

with mango and annāsikā dōsi made with pineapple.<br />

Among the other dainties indulged by the <strong>Moor</strong>s may be included palahāram<br />

which is made by mixing flour, egg and coconut milk after which it is cut into<br />

squares or some other shape and fried. This is then tossed into a syrup made of<br />

47<br />

Maskat appears to be of Arab origin and may have taken its name from the capital of Oman Masqat which<br />

has been renowned for this sweetmeat. Robert Binning (A Journal of Two years travel in Persia, Ceylon<br />

etc.1857) says that in Muscat is made a kind of sweetmeat called halwa-composed of the starch of wheat,<br />

fine sugar, rasped almonds and clarified butter. He adds that this sweetmeat is made in large quantities and<br />

exported to different parts of India and Persia where it is greatly esteemed.<br />

48<br />

Although a well known Hindustani sweetmeat, jalebi probably has its origins in the zalābiya of the Arabs<br />

among whom it has been known for centuries. For instance in the Tale of Dalilah the Crafty and her daughter<br />

Zaynab occurring in the Alf Layla Wa Layla we come across a reference to these honey-fritters (zalābiya bi<br />

asal) being consumed in Baghdad.<br />

49<br />

This delectable item of food is of Hindustani origin. It literally means ‘rose-apple’

sugar, water and rose-water and stored to be consumed at leisure or at some festive<br />

occasion. Another type of palahāram, the suruttu palahāram is similarly made<br />

save that the dough is formed into little boluses which are then flattened and rolled,<br />

hence the name suruttu ‘roll, scroll or cigar’. It is especially known among the<br />

<strong>Moor</strong>s of the Eastern districts like Trincomalee. Another typical eastern<br />

sweetmeat, ellu comprises of little boluses made of grated coconut, roasted<br />

gingelly and jaggery. Yet another known as ellu kali is prepared by cooking in<br />

coconut milk a mixture of roasted rice flour, roasted gingelly, black gram, sugar,<br />

cinnamon and cardamoms. Poribulāṅga, well known in the south though rarely<br />

made nowadays is prepared by mixing roasted and ground white rice, grated<br />

coconut and jaggery to form little boluses very much resembling the woodapple,<br />

hence its name 50 . There is also surtappam (lit.rolled cake) a pancake filled with a<br />

mixture of grated coconut, melted jaggery and cardamoms, and aval, a mixture of<br />

beaten rice, sliced bananas, grated jaggery and thick coconut milk 51 .<br />

There is however one item of food that has a universal appeal among the<br />

<strong>Moor</strong>s, and that is the date (īcca palam) which figures significantly in the life of<br />

the community, especially on religious occasions. Although there exists a variety<br />

of date palm peculiar to the island known as iňdi or the Ceylon Date Palm<br />

(Phoenix zeylanicus) which is found in the southern coast and which yields a sweet<br />

edible pulp, it is not produced on a commercial scale and the dates consumed<br />

locally are usually imported from Iraq and Saudi Arabia 52 . The <strong>Moor</strong>s of the east<br />

such as the Batticaloa region are said to have been so fond of dates that they used<br />

to store them in pots filled with bees’ honey which is said to have made a most<br />

delicious dessert.<br />

50<br />

This item may have had its origins in the T.porivilāṅkāi ‘cake of baked meal, resembling vilām fruit’<br />

(Winslow 1862)<br />

51<br />

Some traditional <strong>Moor</strong> recipes peculiar to the East may be found in Cultural Rhapsody. Ceremonial Food and<br />

Rituals of Sri Lanka by Vinodini De Silva while those peculiar to the South may be found in Southern Pride<br />

<strong>Muslim</strong> Cookery Book by Zohara Vilcassim.<br />

52<br />

The date has figured significantly in the life of the Arab since time immemorial and an old Arab tradition<br />

has it “Honour your aunt, the palm, which was made of the same clay as Adam” (Husn Al- Muhādarah.Suyūti<br />

1321). A saying of the Prophet also has it that “There is a tree among the trees which is similar to a <strong>Muslim</strong>, and<br />

that is the date-palm tree” (Bukhāri)