Co-ordinating Sustainable Cotton Chains for the Mass Market

Co-ordinating Sustainable Cotton Chains for the Mass Market

Co-ordinating Sustainable Cotton Chains for the Mass Market

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Co</strong>-<strong>ordinating</strong> <strong>Sustainable</strong> <strong>Co</strong>tton<br />

<strong>Chains</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mass</strong> <strong>Market</strong><br />

The Case of <strong>the</strong> German Mail-Order Business OTTO<br />

*<br />

Maria Goldbach and Stefan Seuring<br />

Carl von Ossietzky University Oldenburg, Germany<br />

Simone Back<br />

OTTO, Germany<br />

Traditionally, <strong>the</strong> textile market is characterised by spot-market transactions which consider<br />

environmental criteria only at <strong>the</strong> final product level. Yet <strong>the</strong> introduction of<br />

environmentally optimised products is not only a technical problem but also an organisational<br />

one. This fact was encountered by <strong>the</strong> German mail-order business OTTO GmbH,<br />

Hamburg, when it first began to green its clothing collection in <strong>the</strong> early 1990s. While<br />

initially improvements were aimed at <strong>the</strong> product level, in 1997 OTTO decided to go one<br />

step fur<strong>the</strong>r. The objective was to provide organic cotton clothing <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> high-fashion<br />

mass market. The challenge was to realise a value-adding process in which economic,<br />

environmental and social aspects would be equally respected.<br />

OTTO <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e decided to adapt its conventional chain and make it sustainable. The<br />

chain is highly complex, and includes small players such as cotton farmers as well as<br />

large companies such as OTTO itself. The major difficulty arising was how to co-ordinate<br />

<strong>the</strong> activities of <strong>the</strong> complex network of <strong>the</strong> different partners involved. Such co-ordination<br />

may require a set of hybrid approaches, ranging from market-like structures to hierarchical<br />

ones based on command-and-control mechanisms. These are discussed in <strong>the</strong><br />

context of a case study on <strong>the</strong> introduction of a sustainable cotton chain at OTTO.<br />

Dr Maria Goldbach studied Business Administration and Environmental<br />

Management in Kassel, Germany, and Bordeaux, France. She worked at <strong>the</strong><br />

Chair <strong>for</strong> Production and <strong>the</strong> Environment, Institute <strong>for</strong> Business<br />

Administration at <strong>the</strong> University of Oldenburg, Germany, and did her PhD on<br />

‘<strong>Co</strong>-<strong>ordinating</strong> Supply <strong>Chains</strong> with Target <strong>Co</strong>sting and Eco-Target <strong>Co</strong>sting’.<br />

Her research areas are environmental management, cost management and<br />

organisation.<br />

Dr Stefan Seuring is currently a senior lecturer at <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chair of Production<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Environment at <strong>the</strong> University of Oldenburg, Germany, where he<br />

established <strong>the</strong> Supply Chain Management Centre. He holds an MSc in<br />

Chemistry, an MSc in Environmental Management, a PhD and <strong>the</strong> habilitation<br />

in business administration. He has published widely on supply chain<br />

management and environmental/sustainability management.<br />

Simone Back studied nutritional science and home economics and Total<br />

Quality Management in Gießen and Kaiserslautern, Germany. She has extensive<br />

experience in environmental product and process innovations <strong>for</strong> textiles,<br />

food and retailing, where she worked <strong>for</strong> Hess Naturtextilien and <strong>for</strong> BUND<br />

eV (Friends of <strong>the</strong> Earth Germany). From 2000 to 2002 she was responsible<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> organic cotton project at OTTO GmbH, Hamburg. Currently, she is a<br />

freelance consultant focusing on sustainability in supply chains.<br />

u<br />

● Supply chain<br />

management<br />

● <strong>Sustainable</strong><br />

development<br />

● <strong>Co</strong>-ordination<br />

● Transaction<br />

costs<br />

● Textile and<br />

apparel industry<br />

● Organic cotton<br />

● Case study<br />

Gederfeldweg 41, 58453 Witten,<br />

Germany<br />

! maria.goldbach@gmx.net<br />

u<br />

Chair <strong>for</strong> Production and <strong>the</strong><br />

Environment, Institute of Business<br />

Administration, Carl von Ossietzky<br />

University Oldenburg, PO Box 2503,<br />

26111 Oldenburg, Germany<br />

! stefan.seuring@uni-oldenburg.de<br />

u<br />

progresso, Borngasse 14,<br />

55126 Mainz, Germany<br />

! Simone.Back@t-online.de<br />

* This paper was written in <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> research project EcoMTex (Ecological <strong>Mass</strong> Textiles),<br />

which is funded by <strong>the</strong> German Federal Ministry <strong>for</strong> Education and Research (BMBF) and administrated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> National Research Center <strong>for</strong> Environment and Health (GSF). We would like to express<br />

our gratitude to both <strong>the</strong> BMBF and <strong>the</strong> GSF <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir financial and administrative support.<br />

GMI 43 Autumn 2003 © 2004 Greenleaf Publishing 65

maria goldbach, stefan seuring and simone back<br />

The creation of a sustainable product chain does not rely only on <strong>the</strong><br />

technical feasibility of ecological and social improvements, including <strong>the</strong> management<br />

of related material and in<strong>for</strong>mation flows. A major challenge also lies in <strong>the</strong><br />

management and co-ordination of <strong>the</strong> relationships between <strong>the</strong> partners in <strong>the</strong><br />

chain (Goldbach 2002, 2003; Seuring 2004a). Traditionally, <strong>the</strong> apparel industry<br />

has been characterised by market co-ordination based on price (Abernathy et al. 1999;<br />

Seuring 2001: 72). And sustainable cotton, yarn, fabrics and apparel are not available<br />

on <strong>the</strong> market, which may be explained by lack of demand by consumers (Meyer 2000).<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, in order to produce such apparel, o<strong>the</strong>r co-ordination mechanisms are<br />

required. The question that arises is which mechanisms (if not <strong>the</strong> market) allow <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> co-ordination of activities necessary in order <strong>for</strong> sustainable clothing to succeed in<br />

a highly complex network of different partners?<br />

The German mail-order business OTTO has been looking to market sustainable<br />

clo<strong>the</strong>s since 1997, so this case promises insight into <strong>the</strong> necessary co-ordination<br />

scenarios <strong>for</strong> sustainable product chains, using <strong>the</strong> example of sustainable cotton.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> first section, <strong>the</strong> ecological and social impacts of conventional cotton chains<br />

will be described and <strong>the</strong> characteristics of sustainable cotton chains introduced. In <strong>the</strong><br />

next section, different co-ordination mechanisms <strong>for</strong> sustainable product chains will be<br />

discussed. The following section looks at <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical findings from <strong>the</strong> OTTO example<br />

and examines <strong>the</strong> different co-ordination scenarios in a conventional cotton chain as<br />

well as in a sustainable cotton chain.<br />

Ecological and social impacts of cotton chains<br />

<strong>Co</strong>nventional cotton chains<br />

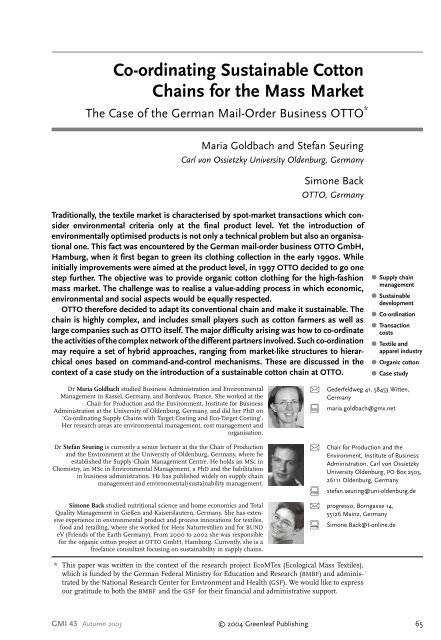

The value-adding process <strong>for</strong> cotton apparel, illustrated in Figure 1, consists of six supply<br />

chain levels (van Elzakker 1999b):<br />

1. Fibre production. <strong>Co</strong>tton fibres are produced by farming, which includes growing<br />

and harvesting cotton fibres as well as cleaning <strong>the</strong>m, which is known as ‘ginning’.<br />

2. Spinning. In <strong>the</strong> spinning mill, <strong>the</strong> cotton fibres are trans<strong>for</strong>med into yarn.<br />

3. Fabric production. At <strong>the</strong> next value-adding level, <strong>the</strong> cotton yarn is processed into<br />

fabrics by weaving or knitting.<br />

4. Dyeing and finishing. Dyeing includes colouring and bleaching of <strong>the</strong> fabric;<br />

finishing consists of processes such as <strong>for</strong>m stabilisation or easy-care treatment.<br />

5. Clothing production. This includes sewing as well as adding accessories such as<br />

zippers, buttons, etc.<br />

6. Clothing retailing. Finally, <strong>the</strong> ready-made apparel is distributed and sold to <strong>the</strong><br />

consumer.<br />

In conventional value-adding cotton chains, ecological and social impacts occur at<br />

different levels, though with varying intensity. 1 <strong>Co</strong>tton farming, i.e. <strong>the</strong> fibre-production<br />

stage, is a particularly critical process, having major ecological and social impacts.<br />

Ecological impacts include <strong>the</strong> intensive use of pesticides, syn<strong>the</strong>tic fertilisers and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

1 See Fig. 1. For a more detailed description of <strong>the</strong> environmental and social impacts of cotton farming,<br />

see Myers and Stolton 1999; van Elzakker 1999b; Meyer and Hohmann 2000.<br />

66 GMI 43 Autumn 2003

co-<strong>ordinating</strong> sustainable cotton chains <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> mass market<br />

Ecological<br />

t Energy intensity<br />

Ecological<br />

t Low impacts<br />

Social<br />

t Labour conditions<br />

t Minimum wages<br />

t Child labour<br />

fibre<br />

production<br />

spinning<br />

fabric<br />

production<br />

dyeing/<br />

finishing<br />

clothing<br />

production<br />

clothing<br />

retailing<br />

Ecological<br />

t Intensive use of pesticides, syn<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

fertilisers and o<strong>the</strong>r agricultural chemicals<br />

t Soil exhaustion and destruction of soils’<br />

self-regeneration capacity<br />

t Disturbance of soils’ water balance,<br />

drying-out and contamination of water<br />

sources<br />

t Use of agricultural land<br />

Social<br />

t High impacts of pesticides and chemicals<br />

on human health<br />

t Financial dependence on pesticide,<br />

syn<strong>the</strong>tic fertilisers and chemical<br />

companies<br />

t Instability of cotton prices<br />

Ecological<br />

t Toxicity of chemicals<br />

(dyestuff and additives)<br />

t Pollution of waste-water<br />

and insufficient<br />

degradability<br />

t Use of AOX,<br />

<strong>for</strong>maldehyde and heavy<br />

metals<br />

t Water and energy<br />

consumption<br />

Social<br />

t Medium impacts on<br />

human health<br />

Ecological and/or<br />

social impacts<br />

Low<br />

Medium<br />

High<br />

Figure 1 ecological and social impacts in a cotton chain<br />

agricultural chemicals. The use of syn<strong>the</strong>tic fertilisers leads to soil exhaustion and <strong>the</strong><br />

destruction of its self-regeneration capacity. Pesticides are proven to contaminate water<br />

sources vital <strong>for</strong> cotton farming. The high water intensity of cotton farming may cause<br />

a disturbance of <strong>the</strong> natural water balance of <strong>the</strong> soil and a depletion of natural water<br />

sources, leading to <strong>the</strong> pesticides used seeping into water resources such as groundwater,<br />

rivers and lakes. Problems from <strong>the</strong> drying-up of soils are most apparent in <strong>the</strong><br />

Aral Sea region (a vast freshwater lake), where cotton farming has contributed to <strong>the</strong><br />

halving of <strong>the</strong> lake’s size (Enquete-Kommission 1994: 148; Myers 1999: 13). Ano<strong>the</strong>r,<br />

often overlooked problem is <strong>the</strong> use of agricultural land <strong>for</strong> cotton farming. If <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

population of <strong>the</strong> world had to be provided with cotton clo<strong>the</strong>s, <strong>the</strong>re would not be<br />

sufficient space <strong>for</strong> nutritional farming (Enquete-Kommission 1994: 145). From a social<br />

perspective, <strong>the</strong> pesticides used are known to be toxic to humans, and lead to between<br />

3,000 and 40,000 fatalities per year (Enquete-Kommission 1994: 149; Myers 1999: 13).<br />

These pesticides are carried through to <strong>the</strong> dyeing and finishing stages, causing minor<br />

ecological problems at <strong>the</strong> different production levels. Moreover, cotton farmers are<br />

often highly dependent on producers of pesticides, syn<strong>the</strong>tic fertilisers and o<strong>the</strong>r chemicals.<br />

Finally, <strong>the</strong> high instability and variety of prices <strong>for</strong> raw cotton on <strong>the</strong> spot market<br />

GMI 43 Autumn 2003 67

maria goldbach, stefan seuring and simone back<br />

lead to severe financial insecurity <strong>for</strong> farmers, many of whom struggle to deal with such<br />

stress, leading to health problems (Enquete-Kommission 1994: 149; Myers 1999).<br />

The spinning and fabric-production stages are not as critical as regards ecological and<br />

social impacts. Ecological impacts occur mainly due to <strong>the</strong> energy intensity of <strong>the</strong><br />

processes. Also, small amounts of comparatively harmless chemicals are used during<br />

processing. No significant social impacts can be identified at <strong>the</strong>se stages.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> dyeing and finishing stages, <strong>the</strong> conventional cotton industry uses toxic chemicals,<br />

which contaminate <strong>the</strong> waste-water and are non-degradable. Moreover, some of <strong>the</strong><br />

substances, such as AOX, <strong>for</strong>maldehyde or heavy metals, are also liable to have human<br />

health impacts. The use of water and energy is also significant in dyeing and finishing.<br />

Ecological impacts in <strong>the</strong> clothing-production stage are minor. However, toxic<br />

chemicals, particularly <strong>the</strong> stain remover used after sewing, are often used without due<br />

labour safety precautions. In small firms especially, health and safety standards are low.<br />

Social impacts are highly significant at <strong>the</strong> clothing-production stage, and working<br />

conditions, minimum wage levels, insufficient labour rights and child labour are issues<br />

often raised. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) investigates and reports on<br />

such conditions (Enquete-Kommission 1994: 158-61; www.ilo.org).<br />

The ecological and social impacts of retailing are relatively minimal. Ecological<br />

impacts also occur at <strong>the</strong> consumption and disposal stages, but <strong>the</strong>se are not within <strong>the</strong><br />

scope of this paper. Also, transportation between <strong>the</strong> different value-adding levels along<br />

<strong>the</strong> chain has ecological impacts. These, too, may be relatively significant, especially at<br />

<strong>the</strong> retailing stage; however, <strong>the</strong>y will not be discussed in this paper, as <strong>the</strong> problem is<br />

of equal significance <strong>for</strong> both conventional and sustainable cotton chains.<br />

<strong>Sustainable</strong> cotton chains<br />

The trans<strong>for</strong>mation process of turning conventional cotton chains into sustainable ones<br />

itself has ecological, social and economic effects which must be taken into consideration.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> farming stage, pesticides and o<strong>the</strong>r chemicals are replaced by biological pest<br />

control and organic fertilisers. Organic cotton farming is an integrated farming<br />

approach without pesticides and one that respects <strong>the</strong> soil’s natural regeneration cycles.<br />

This has not only positive effects on <strong>the</strong> natural environment (i.e. <strong>the</strong> soil) but positive<br />

social effects as well, by not harming human health. Ecological improvements at <strong>the</strong><br />

farming stage have important cost effects: <strong>the</strong>se can be seen in, <strong>for</strong> example, higher<br />

prices <strong>for</strong> organic cotton due to <strong>the</strong> so-called ‘transfair premium’ paid to organic cotton<br />

farmers. The transfair premium aims to compensate <strong>for</strong> possible harvest losses caused<br />

by switching to organic cotton and <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> increased amount of manual work required.<br />

In addition, organic cotton needs to be certified, incurring certification costs. The<br />

sustainability-based improvements <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e lead to positive social effects by assuring<br />

higher cotton prices and often lower production costs <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> cotton farmers. The social<br />

risk <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> farmers consists of requiring customer demand <strong>for</strong> organic cotton. No<br />

market <strong>for</strong> organic cotton currently exists, so, in a worst-case scenario, organic cotton<br />

farmers would have to sell <strong>the</strong>ir cotton on <strong>the</strong> conventional spot market at a lower price,<br />

which does not cover <strong>the</strong> extra costs (even taking <strong>the</strong> transfair premium into account).<br />

Moreover, <strong>the</strong> conversion is highly time-consuming. In fibre production, <strong>for</strong> example,<br />

<strong>the</strong> transition period from conventional to organic cotton is about 3–5 years because of<br />

pesticide residues in <strong>the</strong> soil and <strong>the</strong> lack of natural soil fertility (Myers 1999). During<br />

<strong>the</strong> conversion period, <strong>the</strong> yield is much lower than it will be later and <strong>the</strong> premium<br />

paid to <strong>the</strong> farmers is not as high as <strong>for</strong> certified organic cotton.<br />

In spinning and fabric production, <strong>the</strong> major change consists of using organic instead<br />

of conventional cotton, so minor ecological problems linked to pesticide residues in<br />

cotton are eliminated. However, negative effects occur at an economic level. As <strong>the</strong><br />

68 GMI 43 Autumn 2003

co-<strong>ordinating</strong> sustainable cotton chains <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> mass market<br />

overall amount of organic cotton supplied is often (at least in <strong>the</strong> beginning) not<br />

sufficient to reserve permanent production capacities <strong>for</strong> organic cotton, firms must set<br />

up parallel production capacity, which incurs higher costs, i.e. through separate storage<br />

and handling, and additional cleaning and switching processes. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, different<br />

market structures lead to difficulties in trading. The market <strong>for</strong> organic raw cotton, as<br />

well as <strong>the</strong> consumer market, is small and not comparable with <strong>the</strong> spot market <strong>for</strong><br />

conventional cotton. This leads to higher financial risks.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> dyeing and finishing stage, <strong>the</strong> challenge lies in using low-toxicity dyestuff and<br />

auxiliaries wherever possible, e.g. by substituting chemical with mechanical <strong>for</strong>m<br />

stabilisation and by reducing easy-care treatment to <strong>the</strong> necessary minimum.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> substitution of chemicals may sometimes lead to higher costs <strong>for</strong><br />

ecologically optimised cotton clothing, it is also possible to keep <strong>the</strong> cost level equal or<br />

even reduce <strong>the</strong> total production costs if <strong>the</strong> substitution is combined with more waterand<br />

energy-efficient processes. Higher costs are temporarily incurred through switching<br />

and setting up parallel production. In addition, production quantities of ecologically<br />

optimised garments are still relatively low owing to <strong>the</strong> limited availability of organic<br />

cotton as well as low demand, 2 resulting in higher costs linked to small quantity effects.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> clothing-production stage, control of social effects is managed through <strong>the</strong><br />

introduction of SA8000, a standard aimed at improving working conditions, labour<br />

rights and wages, and defining conditions <strong>for</strong> child labour.<br />

Finally, higher costs result from increased co-ordination ef<strong>for</strong>ts in sustainable cotton<br />

chains which become necessary due to <strong>the</strong> limited availability of organic cotton fibres<br />

and yarns (Meyer and Hohmann 2000: 59; Seuring 2001b: 152; Goldbach 2001; Ton<br />

1999). <strong>Sustainable</strong> cotton and yarn cannot be purchased on markets, so <strong>the</strong> transactions<br />

between <strong>the</strong> different actors along <strong>the</strong> chain must be co-ordinated differently than <strong>the</strong>y<br />

would be through a purely market-based system. In <strong>the</strong> next section, co-ordination<br />

scenarios permitting transactions in sustainable product chains will be introduced and<br />

discussed.<br />

<strong>Co</strong>-ordination scenarios <strong>for</strong> sustainable cotton chains<br />

The major challenge in trans<strong>for</strong>ming conventional cotton chains into sustainable ones<br />

lies not in <strong>the</strong> technical feasibility of introducing ecological and social standards but in<br />

<strong>the</strong> management and co-ordination of <strong>the</strong> actors involved (Goldbach 2003; Kogg 2003;<br />

Seuring 2004a). Williamson distinguishes three different <strong>for</strong>ms of institutional arrangements<br />

allowing transaction co-ordination between economic actors (Williamson 1975,<br />

1985). These are market arrangements, hierarchical arrangements and hybrid arrangements.<br />

The choice of a suitable institutional arrangement is made with <strong>the</strong> objective of<br />

minimising transaction costs that arise from <strong>the</strong> need to co-ordinate activities between<br />

economic actors. Three characteristics influence this choice, which include:<br />

t Uncertainty of transaction. Uncertainty is differentiated into parametric uncertainty,<br />

determined by <strong>the</strong> environment, and behavioural uncertainty, i.e. uncertainty<br />

caused by <strong>the</strong> behaviour of <strong>the</strong> transaction partners.<br />

t Asset specificity. Assets include all investments that are carried out in <strong>the</strong> context<br />

of a transaction with a specific partner, such as investments in technology or human<br />

capital.<br />

2 For <strong>the</strong> costs of greening cotton chains, see Chaudhry 1996; van Elzakker 1999a; Goldbach 2001;<br />

Seuring 2001b.<br />

GMI 43 Autumn 2003 69

maria goldbach, stefan seuring and simone back<br />

t Frequency of transaction. The frequency of transaction determines if economies of<br />

scale transpire with regard to production and co-ordination costs.<br />

High transaction-specific assets, high uncertainty and repeated transactions between<br />

partners generally lead to <strong>the</strong> choice of hierarchy as an institutional arrangement, while<br />

low uncertainty of transaction, low asset specificity and single transactions suggest <strong>the</strong><br />

choice of market hierarchy. Hybrid <strong>for</strong>ms (generally referring to any kind of co-operation<br />

between firms) lie between <strong>the</strong>se two extremes (see Table 1).<br />

<strong>Market</strong> <strong>Co</strong>-operation Hierarchy<br />

Uncertainty of transaction – 0 +<br />

Asset specificity – 0 +<br />

Frequency of transaction – 0 +<br />

<strong>Co</strong>-ordination mechanism Price Negotiation <strong>Co</strong>mmand and control<br />

– low, 0 medium, + high<br />

Table 1 choice of institutional arrangements on <strong>the</strong> basis of characteristics<br />

The mechanisms underlying <strong>the</strong> transaction vary according to <strong>the</strong> chosen institutional<br />

arrangement. In markets, price is <strong>the</strong> overriding factor in <strong>the</strong> choice of partner.<br />

In hierarchies, command-and-control measures underlie co-ordination between actors.<br />

The choice of transaction partner is made at <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> transaction and <strong>the</strong><br />

tasks to be carried out are prescribed by <strong>the</strong> principal (Pratt and Zeckhauser 1991; Arrow<br />

1991). Transactions are based on negotiations between <strong>the</strong> actors: <strong>the</strong> choice of partner<br />

has been made, but defining <strong>the</strong> task to be carried out as well as <strong>the</strong> quid pro quo is still<br />

to be agreed. 3<br />

Williamson applies <strong>the</strong>se institutional arrangements only to a single firm or bilateral<br />

transactions between firms. In order to apply to <strong>the</strong> context of making cotton chains<br />

sustainable, <strong>the</strong>y must be extended to value-adding processes or supply chains. Most<br />

authors dealing with supply chain management automatically subsume supply chains<br />

under hybrid arrangements, i.e. between market and hierarchy (Skjoett-Larsen 1999).<br />

This view will be questioned on <strong>the</strong> basis of <strong>the</strong> definition of supply chains and supply<br />

chain management proposed by Handfield and Nichols (1999: 2):<br />

The supply chain encompasses all activities associated with <strong>the</strong> flow and trans<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

of goods from raw materials stage (extraction), through to <strong>the</strong> end user, as well as <strong>the</strong><br />

associated in<strong>for</strong>mation flows. Material and in<strong>for</strong>mation both flow up and down <strong>the</strong><br />

supply chain. Supply chain management (SCM) is <strong>the</strong> integration of <strong>the</strong>se activities<br />

through improved supply chain relationships, to achieve a sustainable 4 competitive<br />

advantage.<br />

If we use Williamson’s distinction of three <strong>for</strong>ms of institutional arrangements and<br />

co-ordination mechanisms to look at supply chains with low uncertainty, low asset<br />

specificity and low frequency of transaction, we see that market mechanisms may be<br />

<strong>the</strong> most suitable means of <strong>for</strong>ming relationships to achieve sustainable competitive<br />

advantage. In supply chains with high uncertainty, asset specificity and frequency,<br />

3 The three types are idealised <strong>for</strong>ms. In reality, mixed <strong>for</strong>ms exist, e.g. <strong>the</strong> asset specificity may be<br />

high, but <strong>the</strong> frequency of transactions low. In this case it must be determined which of <strong>the</strong><br />

characteristics are more relevant and if <strong>the</strong>se permutations still justify co-operation as <strong>the</strong> suitable<br />

means of co-ordination. These mixed types will not be discussed fur<strong>the</strong>r in this paper.<br />

4 The term ‘sustainable’ in this definition merely refers to long-term-oriented or enduring and does<br />

not correspond to sustainability as integrating environmental, social and economic aspects.<br />

70 GMI 43 Autumn 2003

co-<strong>ordinating</strong> sustainable cotton chains <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> mass market<br />

command-and-control mechanisms may be more appropriate. In any kind of chain with<br />

medium uncertainty, asset specificity and frequency, i.e. <strong>the</strong> kind of arrangement usually<br />

understood to describe a supply chain, negotiation is <strong>the</strong> most efficient means of gaining<br />

sustainable competitive advantage.<br />

This means that, in this paper, supply chains are considered to be a network of actors<br />

involved in <strong>the</strong> value-adding process of a product. Whe<strong>the</strong>r this network is co-ordinated<br />

through price, command and control or negotiation depends on <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong><br />

transactions and <strong>the</strong>ir related characteristics.<br />

Of course, <strong>the</strong>se three types represent ideal <strong>for</strong>ms, even though co-operation seems<br />

to subsume any kind of arrangement that does not correspond to market or hierarchies.<br />

For fur<strong>the</strong>r analysis, it remains to be pointed out that, at a bilateral transaction level<br />

between firms, mixed <strong>for</strong>ms (especially with regard to co-ordination mechanisms) are<br />

possible. Moreover, a number of institutional arrangements and co-ordination mechanisms<br />

may co-exist along <strong>the</strong> entire supply chain. While <strong>the</strong> transaction between a cotton<br />

farmer and a yarn producer may be based on <strong>the</strong> market, i.e. on price as a co-ordination<br />

mechanism, <strong>the</strong> transaction between <strong>the</strong> clothing retailer and its producer may be based<br />

on command and control or on negotiation and vice versa. This co-existence of several<br />

co-ordination mechanisms implies that <strong>the</strong> partners involved in <strong>the</strong> value-adding<br />

process may change: i.e. <strong>the</strong> supply chain is dynamic and no longer static.<br />

The example of <strong>the</strong> German mail-order business OTTO illustrates how changing its<br />

conventional cotton chain into a sustainable one affects <strong>the</strong> co-ordination mechanisms<br />

and <strong>the</strong> structure of institutional arrangements within <strong>the</strong> chain.<br />

<strong>Co</strong>tton chains at OTTO: a case study<br />

The German mail-order business OTTO began introducing ecologically optimised clothing<br />

into its collections in <strong>the</strong> early 1990s. These improvements comprised both cotton<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r fibre collections and aimed at limiting harmful substances at <strong>the</strong> product level.<br />

In 1997, OTTO decided to go one step fur<strong>the</strong>r and to extend beyond <strong>the</strong> production<br />

process back to <strong>the</strong> ‘cradle’ of clothing production, <strong>the</strong> cotton plant. The objective was<br />

to provide organic cotton clothing <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> high-fashion mass market. The challenge was<br />

to achieve a value-adding process in which economic, ecological and social aspects would<br />

be equally respected. The new sustainable cotton clo<strong>the</strong>s were not to cost significantly<br />

more than conventional ones and at <strong>the</strong> same time would maintain OTTO’s high quality<br />

and fashion standards.<br />

The major difficulty arising in this context was not so much how to solve <strong>the</strong> technical<br />

problems, but ra<strong>the</strong>r how to co-ordinate <strong>the</strong> activities of <strong>the</strong> highly complex network of<br />

<strong>the</strong> different partners involved. In <strong>the</strong> following, <strong>the</strong> co-ordination scenarios of a conventional<br />

and a sustainable cotton chain are presented and discussed.<br />

<strong>Co</strong>-<strong>ordinating</strong> <strong>the</strong> conventional cotton chain at OTTO<br />

In <strong>the</strong> conventional cotton chain, OTTO is in direct contact only with <strong>the</strong> clothing producers.<br />

For <strong>the</strong> sake of simplicity, <strong>the</strong> focus here will be on fully integrated clothing<br />

producers, i.e. those carrying out fabric production, dyeing and finishing as well as<br />

clothing production all within <strong>the</strong> one company.<br />

At OTTO, purely market-based co-ordination based on spot-market transactions, <strong>the</strong><br />

usual mechanism in <strong>the</strong> conventional textile industry, is partly mitigated by reducing<br />

<strong>the</strong> supplier base and building long-term supplier relationships. During <strong>the</strong> 1990s,<br />

OTTO began setting up a supplier pool. The different buying departments at OTTO could<br />

GMI 43 Autumn 2003 71

maria goldbach, stefan seuring and simone back<br />

freely choose any supplier within this pool that best met <strong>the</strong> requirements <strong>for</strong> a specific<br />

article. Thus co-ordination through purely market-based transactions was replaced by a<br />

<strong>for</strong>m of co-ordination limiting <strong>the</strong> scope of action to this supplier pool but maintaining<br />

flexibility within it. It <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e corresponds to a mixed co-ordination scenario of cooperation<br />

(concerning <strong>the</strong> setting-up of <strong>the</strong> pool) and market (within <strong>the</strong> pool), i.e.<br />

negotiation and price mechanisms.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> early 1990s, OTTO began optimising its conventional cotton chain by limiting<br />

<strong>the</strong> amount of harmful substances at a product level. It introduced an internal standard,<br />

called hautfreundlich, weil schadstoffgeprüft (‘skin-friendly, because tested <strong>for</strong> harmful<br />

substances’) which basically corresponds to Öko-Tex 100—a German standard controlling<br />

human toxicological effects at <strong>the</strong> textile product level—but is stricter as regards<br />

certain categories and permissible limits. The desired improvements were achieved<br />

using suppliers from <strong>the</strong> pool that were approved eco-suppliers (AES). Currently, 80%<br />

of products meet OTTO’s ecological requirements, and by 2004 this will rise to 100%.<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, this first level of environmental optimisation does not constitute an extra<br />

selection criterion within <strong>the</strong> existing pool of suppliers, but is established as a standard<br />

which may be interpreted as an additional quality requirement.<br />

The introduction of this standard affects only <strong>the</strong> direct suppliers who are involved<br />

in <strong>the</strong> dyeing and finishing processes, i.e. <strong>the</strong> production stage where harmful chemicals<br />

are used, those liable to cause human toxicological problems that are connected to <strong>the</strong><br />

final product. There<strong>for</strong>e, <strong>the</strong> structure of <strong>the</strong> conventional cotton chain beyond <strong>the</strong><br />

clothing producers is not affected, as changes occur only with regard to <strong>the</strong> internal<br />

production processes of <strong>the</strong> clothing producer.<br />

The interaction between OTTO and its clothing producer is based on co-operation (i.e.<br />

negotiation), and interactions within <strong>the</strong> pool are based on <strong>the</strong> market (i.e. price<br />

mechanisms).<br />

Interactions beyond <strong>the</strong> bilateral one between OTTO and its clothing producer do not<br />

concern OTTO. Interaction between <strong>the</strong> fully integrated clothing producer (from <strong>the</strong><br />

point of view of fabric production) and <strong>the</strong> spinner relies on a mix of price and<br />

negotiation. There is co-operation between <strong>the</strong> fabric producers and spinners, so <strong>the</strong><br />

scenario is similar to <strong>the</strong> one between OTTO and <strong>the</strong> clothing producer. The interaction<br />

between <strong>the</strong> fibre producer, i.e. cotton trader, and <strong>the</strong> spinner is based purely on spotmarket<br />

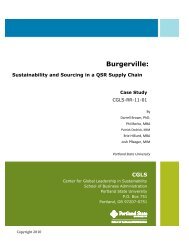

transactions, as conventional cotton is traded on <strong>the</strong> cotton exchange. Figure 2<br />

summarises <strong>the</strong>se findings. 5<br />

fibre<br />

production<br />

spinning<br />

fabric<br />

production<br />

dyeing/<br />

finishing<br />

clothing<br />

production<br />

otto<br />

Price<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Figure 2 co-ordination mechanisms in <strong>the</strong> conventional cotton chain at otto<br />

5 A selection of chains were analysed as examples. There<strong>for</strong>e, <strong>the</strong>se results reveal a general tendency<br />

but may not be valid <strong>for</strong> all chains.<br />

72 GMI 43 Autumn 2003

co-<strong>ordinating</strong> sustainable cotton chains <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> mass market<br />

<strong>Co</strong>-<strong>ordinating</strong> <strong>the</strong> sustainable cotton chain at OTTO<br />

In analysing <strong>the</strong> sustainable cotton chain, two major differences to a conventional chain<br />

can be distinguished. First, <strong>the</strong> co-ordination of <strong>the</strong> initial phase, i.e. <strong>the</strong> one within<br />

which measures need to be taken to set up <strong>the</strong> chain, was significantly different from<br />

<strong>the</strong> advanced phase, i.e. <strong>the</strong> one within which <strong>the</strong> chain needs to be maintained in <strong>the</strong><br />

medium term. Second, bilateral co-ordination between neighbouring partners at a more<br />

operational level in <strong>the</strong> conventional chain was complemented by a chain-wide level,<br />

below also referred to as a global level. There<strong>for</strong>e, in <strong>the</strong> following, analysis of <strong>the</strong><br />

sustainable cotton chain at OTTO is presented in two steps: <strong>the</strong> first concerning <strong>the</strong> initial<br />

phase and <strong>the</strong> second <strong>the</strong> advanced phase. In <strong>the</strong> conventional chain, which is already<br />

in place at OTTO, such a distinction is not necessary, <strong>the</strong> conventional chain implying<br />

an advanced phase.<br />

The initial phase<br />

When OTTO decided to extend its ecological and social ambitions to <strong>the</strong> entire production<br />

process in 1997, no market existed that would ‘naturally’ co-ordinate sustainability<br />

processes within cotton chains. OTTO decided to fall back on fully integrated partners<br />

from its conventional cotton chain and convince <strong>the</strong>m to become sustainable. It was<br />

decided to proceed with <strong>the</strong> planned ecological programme with those companies that<br />

had already passed an audit <strong>for</strong> social accountability. The structure of <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

partners within this chain is quite complex, including small players such as numerous,<br />

anonymous cotton farmers as well as big companies such as OTTO itself. The necessary<br />

changes were so significant that <strong>the</strong>y fundamentally affected <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong> interaction<br />

with OTTO’s direct suppliers as well as <strong>the</strong> entire chain structure.<br />

OTTO’s existing fully integrated clothing producers from <strong>the</strong> supplier pool did not<br />

have at <strong>the</strong>ir disposal <strong>the</strong> necessary know-how and technology to make <strong>the</strong>ir dyeing and<br />

finishing processes sustainable and were <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e (at first) unable to put into practice<br />

<strong>the</strong> required improvements. OTTO <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e selected specific suppliers from <strong>the</strong> pool<br />

considered to have <strong>the</strong> potential to become sustainable. It supported <strong>the</strong>se in acquiring<br />

<strong>the</strong> necessary know-how through a consultancy process on technology adaptation. In<br />

contrast to its conventional chain, OTTO built up fixed, long-term-oriented relationships<br />

with <strong>the</strong>se suppliers. This meant that <strong>the</strong> buying departments were now restricted to<br />

choosing from among those suppliers that had been assessed and evaluated. In some<br />

cases, only one single supplier was eligible to supply a specific article.<br />

Apart from changing relationships with clothing suppliers, prior stages in <strong>the</strong> chain<br />

were also affected as <strong>the</strong> programme was aimed at <strong>the</strong> entire chain, all <strong>the</strong> way back to<br />

<strong>the</strong> farmers. <strong>Co</strong>nventionally grown cotton was to be replaced by organic cotton because<br />

of <strong>the</strong> high ecological and social impacts of conventional farming, outlined above.<br />

As OTTO’s fully integrated clothing suppliers—more specifically, <strong>the</strong> fabric-production<br />

departments—had no business relationships with sustainable yarn or cotton<br />

traders, OTTO itself sought suitable sustainable cotton partners and spinning companies.<br />

As OTTO does not usually interact with <strong>the</strong> cotton and yarn traders directly, this<br />

meant dealing with two new trading partners in <strong>the</strong> cotton chain. The ones <strong>the</strong>y selected<br />

were already ecologically motivated and already possessed <strong>the</strong> required know-how.<br />

Moreover, <strong>the</strong>y met OTTO’s social requirements.<br />

At first, OTTO was required to actively organise and co-ordinate <strong>the</strong> chain. OTTO<br />

bought <strong>the</strong> organic cotton directly and arranged transport to <strong>the</strong> spinning mill, negotiated<br />

spinning and yarn prices with <strong>the</strong> spinning mill, and arranged <strong>the</strong> transfer of <strong>the</strong><br />

organic yarn to <strong>the</strong> fully integrated clothing producer. OTTO entered <strong>the</strong> chain as an<br />

interim actor between <strong>the</strong> cotton trader and <strong>the</strong> spinner, as well as between <strong>the</strong> spinner<br />

and <strong>the</strong> clothing producer. The usual interaction between cotton trader and spinner, as<br />

well as between spinner and fully integrated clothing producer, was thus dissolved. So<br />

GMI 43 Autumn 2003 73

maria goldbach, stefan seuring and simone back<br />

<strong>the</strong> original chain structure was broken up, as OTTO began by co-<strong>ordinating</strong> all levels<br />

along <strong>the</strong> chain, not only with <strong>the</strong> fully integrated clothing producer but also with <strong>the</strong><br />

yarn and <strong>the</strong> cotton trader.<br />

In this chain, two levels of co-ordination could be distinguished: <strong>the</strong> chain-wide,<br />

global level and <strong>the</strong> bilateral, operational level. On <strong>the</strong> global level, <strong>the</strong> structure of <strong>the</strong><br />

chain was determined. The fully integrated clothing producer, based on command-andcontrol<br />

mechanisms, was instructed to use <strong>the</strong> organic yarn from <strong>the</strong> spinning mill<br />

chosen by OTTO. The relationships with <strong>the</strong> spinning mill and <strong>the</strong> cotton trader were<br />

built up on a partnership basis, i.e. co-operation, based on negotiation between partners.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> operational level, <strong>the</strong> bilateral relationships between <strong>the</strong> cotton trader and OTTO<br />

are based on negotiation and price. The interactions between OTTO and <strong>the</strong> spinner, <strong>the</strong><br />

spinner and OTTO, and OTTO and <strong>the</strong> fully integrated clothing producer are based on<br />

command and control, with OTTO instructing <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r actors in <strong>the</strong> chain on how to<br />

interact. Interaction between <strong>the</strong> clothing producer and OTTO is based on a mix of<br />

negotiation and price mechanisms. These findings are summarised in Figure 3.<br />

Negotiation<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand and control<br />

fibre<br />

production<br />

otto<br />

spinning<br />

otto<br />

fabric<br />

production<br />

dyeing/<br />

finishing<br />

clothing<br />

production<br />

otto<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand<br />

and control<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand<br />

and control<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand<br />

and control<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Figure 3 co-ordination mechanisms in <strong>the</strong> sustainable cotton chain at otto: initial phase<br />

The advanced phase<br />

The sustainable cotton chain has been consolidated within <strong>the</strong> last two years, so OTTO<br />

can now build <strong>the</strong> co-ordination of <strong>the</strong> chain on an established chain structure. The coordination<br />

of <strong>the</strong> entire chain by OTTO has been superseded by negotiation between all<br />

partners, including <strong>the</strong> fully integrated clothing producers, at a chain-wide level. OTTO<br />

still offers recommendations, and controls where <strong>the</strong> different partners can acquire<br />

materials—i.e. where <strong>the</strong> yarn trader can purchase its organic cotton and where <strong>the</strong><br />

fabric producer can buy organic yarn—but <strong>the</strong> responsibility <strong>for</strong> achieving <strong>the</strong> goal of<br />

sustainable cotton clo<strong>the</strong>s is increasingly relinquished to <strong>the</strong> chain. Chain-wide coordination<br />

will <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e be entirely based on negotiation.<br />

At a bilateral level, as <strong>the</strong> chain is more settled and responsibility lies in <strong>the</strong> hands of<br />

<strong>the</strong> different partners, co-ordination becomes mainly based on a mixture of price and<br />

negotiation mechanisms. The fabric producer and <strong>the</strong> spinner co-operate, partly influenced<br />

by strong recommendations by OTTO. <strong>Co</strong>-ordination, even though based on<br />

negotiation, is supported by <strong>the</strong> market, i.e. price mechanisms. This phenomenon may<br />

equally be observed in <strong>the</strong> interaction between <strong>the</strong> spinner and <strong>the</strong> fabric producer as<br />

between <strong>the</strong> clothing producer and OTTO itself. The findings are summarised in Figure<br />

4.<br />

74 GMI 43 Autumn 2003

co-<strong>ordinating</strong> sustainable cotton chains <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> mass market<br />

Negotiation<br />

fibre<br />

production<br />

spinning<br />

fabric<br />

production<br />

dyeing/<br />

finishing<br />

clothing<br />

production<br />

otto<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Figure 4 co-ordination mechanisms in <strong>the</strong> sustainable cotton chain at otto:<br />

advanced phase<br />

Summary of <strong>the</strong> different co-ordination scenarios at OTTO<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mparison of <strong>the</strong> conventional, <strong>the</strong> initial sustainable and <strong>the</strong> advanced sustainable<br />

cotton chain at OTTO indicates a development from a market-oriented approach, via a<br />

co-operation-oriented approach, leading to a scenario that is a combination of marketand<br />

co-operation-oriented co-ordination.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> conventional cotton chain, interaction between <strong>the</strong> fibre producer and spinner<br />

is based merely on price; interactions between spinners and fabric producers, as well as<br />

between clothing producers and OTTO, are based on price and negotiation. OTTO’s<br />

interaction with <strong>the</strong> supplier pool as a whole is based on co-operation, while within <strong>the</strong><br />

pool a market exists. There is no global co-ordination within this chain. It is <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e<br />

a ‘market scenario’.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> initial phase of <strong>the</strong> sustainable chain, global co-ordination exists which is<br />

undertaken by OTTO and is based on command and control over <strong>the</strong> fully integrated<br />

clothing producers and on negotiation with <strong>the</strong> cotton and yarn traders. On a bilateral<br />

level, OTTO enters <strong>the</strong> chain as an interim player. Interaction between <strong>the</strong> fibre producer<br />

and OTTO is based on a mix of price and negotiation between OTTO and <strong>the</strong> spinner, <strong>the</strong><br />

spinner and OTTO, OTTO and <strong>the</strong> clothing producer (using command and control) and<br />

between <strong>the</strong> clothing producer and OTTO (using negotiation and price). As regards OTTO<br />

itself, <strong>the</strong> sustainable supplier pool <strong>for</strong>ms a sub-pool within <strong>the</strong> general supplier pool.<br />

This scenario can <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e be referred to as ‘patriarchal co-operation’.<br />

The advanced phase of <strong>the</strong> sustainable chain combines <strong>the</strong> conventional and initial<br />

phase of <strong>the</strong> sustainable chain. Global co-ordination within <strong>the</strong> chain is based on negotiation<br />

and recommendations. It no longer lies merely in <strong>the</strong> purview of OTTO but is<br />

shared with <strong>the</strong> fully integrated clothing producers and spinners. Bilateral interaction<br />

between all partners along <strong>the</strong> chain relies on a mix of price and negotiation elements.<br />

It is <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e influenced by <strong>the</strong> market. This scenario of <strong>the</strong> advanced phase of <strong>the</strong><br />

sustainable cotton chain can <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e be referred to as a ‘co-operative market’. Table 2<br />

sums up <strong>the</strong>se findings.<br />

GMI 43 Autumn 2003 75

maria goldbach, stefan seuring and simone back<br />

<strong>Co</strong>nventional cotton chain<br />

<strong>Sustainable</strong> cotton chain:<br />

initial phase<br />

<strong>Sustainable</strong> cotton chain:<br />

advanced phase<br />

Bilateral,<br />

operational<br />

Chain-wide,<br />

global<br />

Bilateral,<br />

operational<br />

Chain-wide,<br />

global<br />

Bilateral,<br />

operational<br />

Chain-wide,<br />

global<br />

Fibre production<br />

OTTO<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Spinning<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand<br />

and control<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand<br />

and control<br />

OTTO<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

None<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand<br />

and control<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

<strong>Co</strong>mmand<br />

and control<br />

Fabric<br />

production<br />

Dyeing/<br />

finishing<br />

Clothing<br />

production<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

Negotiation<br />

Price<br />

OTTO<br />

<strong>Co</strong>-ordination<br />

scenario<br />

<strong>Market</strong> Patriarchal co-operation <strong>Co</strong>-operative market<br />

Table 2 co-ordination mechanisms in <strong>the</strong> conventional and sustainable cotton chains at<br />

otto<br />

<strong>Co</strong>nclusion and research perspectives<br />

The cotton supply chain is dispersed around <strong>the</strong> globe. This makes <strong>the</strong> move toward<br />

sustainability in such supply chains a complex task. Sustainability management can<br />

<strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e be understood as an implementing measure that ensure that suppliers meet<br />

environmental and social standards, while ensuring that <strong>the</strong> supply chain remains<br />

competitive. This requires increased co-operation among all partners involved in <strong>the</strong><br />

chain. The findings from <strong>the</strong> OTTO case offer insights on how a combination of market<br />

and co-operation seems to be <strong>the</strong> most promising means of fur<strong>the</strong>r improving sustainable<br />

chains and allowing <strong>the</strong>ir survival in <strong>the</strong> marketplace (Goldbach 2003; Kogg 2003).<br />

As <strong>the</strong> market and price are initially not available as co-ordination mechanisms <strong>for</strong><br />

sustainable cotton chains, co-ordination in <strong>the</strong> initial phase is based on negotiation and<br />

even command and control. Once <strong>the</strong> chain has been set up, market elements may be<br />

reintroduced into <strong>the</strong> co-ordination scenario allowing <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> necessary competition and<br />

meeting of market demands.<br />

76 GMI 43 Autumn 2003

co-<strong>ordinating</strong> sustainable cotton chains <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> mass market<br />

The case provides evidence that sustainability in a supply chain cannot be viewed<br />

merely as a technical matter, where products’ life-cycles are analysed and technical<br />

measures are subsequently implemented to ensure that related goals are met. On <strong>the</strong><br />

contrary, <strong>the</strong> management of products’ environmental life-cycle within supply chains<br />

(Seuring 2004a, 2004b) are first of all inter-organisational concepts, where much ef<strong>for</strong>t<br />

has to be placed.<br />

The overarching research question—how to manage <strong>the</strong> transition of supply chains<br />

from conventional product to sustainable products and production processes—will need<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r investigation.<br />

References<br />

Arrow, K.J. (1991) ‘The Economics of Agency’, in J.W. Pratt and R.J. Zeckhauser (eds.), Principals and<br />

Agents: The Structure of Business (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press): 37-51.<br />

Abernathy, F.H., J.T. Dunlop, J.H. Hammond and D. Weil (1999) A Stitch in Time. Retailing and <strong>the</strong><br />

Trans<strong>for</strong>mation of Manufacturing: Lessons from <strong>the</strong> Apparel and Textile Industry (New York/Ox<strong>for</strong>d, UK:<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press).<br />

Chaudhry, M.R. (1996) ‘<strong>Co</strong>st of Producing a Kilogram of <strong>Co</strong>tton’, Proceedings from <strong>the</strong> 23rd International<br />

<strong>Co</strong>tton <strong>Co</strong>nference, Bremen, Germany.<br />

Enquete-Kommission Schutz des Menschen und der Umwelt (1994) ‘Die Industriegesellschaft<br />

gestalten: Perspektiven für einen nachhaltigen Umgang mit Stoff- und Materialströmen’ (‘Designing<br />

Industrial Society: Perspectives <strong>for</strong> Sustainably Managing Substance and Material Flows’),<br />

Economica (Bonn): 101-22.<br />

Goldbach, M. (2001) ‘Managing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Co</strong>sts of Greening: A Supply Chain Perspective’, The 2001 Business<br />

Strategy and <strong>the</strong> Environment <strong>Co</strong>nference, University of Leeds, UK, 10–11 September 2001: 109-18.<br />

—— (2002) ‘Organizational Settings in Supply Chain <strong>Co</strong>sting’, in S. Seuring and M. Goldbach (eds.),<br />

<strong>Co</strong>st Management in Supply <strong>Chains</strong> (Heidelberg, Germany: Physica): 89-108.<br />

—— (2003) ‘<strong>Co</strong><strong>ordinating</strong> Interaction in Supply <strong>Chains</strong>: The Example of Greening Textile <strong>Chains</strong>’, in<br />

S. Seuring, M. Müller, M. Goldbach and U. Schneidewind (eds.), Strategy and Organization in Supply<br />

<strong>Chains</strong> (Heidelberg, Germany: Physica): 47-63.<br />

Handfield, R.B., and E.L. Nichols, Jr (1999) Introduction to Supply Chain Management (Upper Saddle<br />

River, NJ: Prentice Hall).<br />

Kogg, B. (2003) ‘Power and Incentives in Environmental Supply Chain Management’, in S. Seuring, M.<br />

Müller, M. Goldbach and U. Schneidewind (eds.), Strategy and Organization in Supply <strong>Chains</strong><br />

(Heidelberg, Germany: Physica): 47-63.<br />

Meyer, A. (2001) ‘What’s In It For The Customer? Successfully <strong>Market</strong>ing Green Clo<strong>the</strong>s’, Business<br />

Strategy and <strong>the</strong> Environment 10.5: 317-30.<br />

—— and P. Hohmann (2000) ‘O<strong>the</strong>r Thoughts; O<strong>the</strong>r Results? Remei’s bioRe Organic <strong>Co</strong>tton on its<br />

Way to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mass</strong> <strong>Market</strong>’, Greener Management International 31 (Autumn 2000): 59-70.<br />

Myers, D. (1999) ‘The Problems with <strong>Co</strong>nventional <strong>Co</strong>tton’, in D. Myers and S. Stolton (eds.), Organic<br />

<strong>Co</strong>tton: From Field to Final Product (London: Intermediate Technology Publications): 9-20.<br />

—— and S. Stolton (eds.) (1999) Organic <strong>Co</strong>tton: From Field to Final Product (London: Intermediate<br />

Technology Publications).<br />

Pratt, J.W., and R.J. Zeckhauser (1991) ‘Principals and Agents: An Overview’, in J.W. Pratt and R.J.<br />

Zeckhauser (eds.), Principals and Agents: The Structure of Business (Boston, MA: Harvard Business<br />

School Press).<br />

Seuring, S. (2001a): Green Supply Chain <strong>Co</strong>sting: Joint <strong>Co</strong>st Management in <strong>the</strong> Polyester Linings<br />

Supply Chain’, Greener Management International 33 (Spring 2001): 71-80.<br />

—— (2001b) ‘A Framework <strong>for</strong> Green Supply Chain <strong>Co</strong>sting: A Fashion Industry Example’, in J. Sarkis<br />

(ed.), Greener Manufacturing and Operations: From Design to Delivery and Back (Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf<br />

Publishing): 150-60.<br />

—— (2004a) ‘Integrated Chain Management and Supply Chain Management: <strong>Co</strong>mparative Analysis<br />

and Illustrative Cases’, Journal of Cleaner Production 12.8–10: 1,059-71.<br />

—— (2004b) ‘Industrial Ecology, Life-Cycles, Supply <strong>Chains</strong>: Differences and Interrelations’, Business<br />

Strategy and <strong>the</strong> Environment 13.5: 306-19.<br />

Skjoett-Larsen, T. (1999) ‘Supply Chain Management: A New Challenge <strong>for</strong> Researchers and Managers<br />

in Logistics’, International Journal of Logistics Management 10.2: 41-53.<br />

GMI 43 Autumn 2003 77

maria goldbach, stefan seuring and simone back<br />

Ton, P. (1999) ‘The <strong>Market</strong> <strong>for</strong> Organic <strong>Co</strong>tton’, in D. Myers and S. Stolton (eds.), Organic <strong>Co</strong>tton: From<br />

Field to Final Product (London: Intermediate Technology Publications): 101-20.<br />

Van Elzakker, B. (1999a) ‘<strong>Co</strong>mparing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Co</strong>sts of Organic and <strong>Co</strong>nventional <strong>Co</strong>tton’, in D. Myers and<br />

S. Stolton (eds.), Organic <strong>Co</strong>tton: From Field to Final Product (London: Intermediate Technology<br />

Publications): 86-100.<br />

—— (1999b) ‘Organic <strong>Co</strong>tton Production’, in D. Myers and S. Stolton (eds.), Organic <strong>Co</strong>tton: From Field<br />

to Final Product (London: Intermediate Technology Publications): 21-35.<br />

Williamson, O. (1975) <strong>Market</strong>s and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications (New York: The Free<br />

Press).<br />

—— (1985) The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (New York: The Free Press).<br />

q<br />

78 GMI 43 Autumn 2003