Part IIB – Industry Empirical Studies Lecture 8: Contracts, Incentives ...

Part IIB – Industry Empirical Studies Lecture 8: Contracts, Incentives ...

Part IIB – Industry Empirical Studies Lecture 8: Contracts, Incentives ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Introduction<br />

<strong>Part</strong> <strong>IIB</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>Industry</strong><br />

<strong>Empirical</strong> <strong>Studies</strong><br />

<strong>Lecture</strong> 8: <strong>Contracts</strong>, <strong>Incentives</strong> and<br />

Organization Structure<br />

Dr Christos Genakos<br />

• So far in the course, we have treated firms as black boxes<br />

maximizing their output given their inputs<br />

• Today we are going to take a step back and look inside this<br />

black box<br />

• Fundamental question: Why do firms exist?<br />

• Firms exist to coordinate and motivate people’s economic<br />

activity (why inside the firm and not in the market place?)<br />

• Coordination means, at a minimum, that all needed tasks<br />

are completed without pointless duplication<br />

• Motivation becomes a problem too if it’s not automatically in<br />

the self- interest of individuals to act in ways that promote<br />

realizing an efficient solution to the coordination problem<br />

• Assume that firms exist, look at the source and nature of<br />

motivation problems and in ways to organize the firm for<br />

performance<br />

Introduction<br />

• Main motivation or incentive problems inside the firm:<br />

• Externalities: people’s actions affect others in ways that the<br />

individual does not fully take into account<br />

• Moral hazard: limited observability of actions, cannot specify<br />

rewards and punishments at an individual level<br />

• Free riding: several people contribute to some outcome but<br />

all share the benefits<br />

• All these situations fall under the rubric of “agency<br />

problems”<br />

• The key problem:<br />

<strong>–</strong> an agent acts on behalf of another, called the principal<br />

<strong>–</strong> other things being equal, at the margin the agent prefers<br />

to provide less of the action taken on the principal’s<br />

behalf while the principal prefers more<br />

Introduction<br />

• If the agent’s effort were observable and verifiable to the<br />

courts, then the two parties could simply contract on the<br />

action taken<br />

• Assume principal cannot directly observe the agent’s<br />

actions, but can observe a noisy signal (effort + noise)<br />

• If the agent bore the full benefits and costs of his actions, he<br />

would take the efficient choices<br />

• If agent is risk averse or financially constrained, he cannot<br />

be the full residual claimant<br />

• The principal’s problem is to design an incentive scheme<br />

that trades off the cost of having to compensate the agent<br />

(extra effort and for bearing risk) against the benefits<br />

generated by the extra effort induced by stronger incentives<br />

OUTLINE Performance Pay and Productivity <strong>–</strong> Lazear (2000)<br />

1. Performance Pay and Productivity <strong>–</strong> Lazear (2000)<br />

2. IT, Workplace organization and the demand for Skilled<br />

Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan, Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

3. Measuring and Explaining Management Practices across<br />

firms and countries <strong>–</strong> Bloom and Van Reenen (2007)<br />

• Basic cornerstone of theory is that workers respond to<br />

incentives<br />

• But there is intrinsic as well as extrinsic motivation<br />

• Sociologists claim that monetarizing incentives may<br />

actually reduce output<br />

• Lazear looks at the data from a single company (Safelite<br />

Glass Corp.) which during 1994- 95 gradually changed the<br />

compensation method from hourly wages to piece- rate pay<br />

• One company, but very good data: 3,000 employees over<br />

a 19- month period working under both contracts<br />

• Output easy to measure: auto glass installation (outputper-<br />

worker- per- day)<br />

1

Performance Pay and Productivity <strong>–</strong> Lazear (2000)<br />

Performance Pay and Productivity <strong>–</strong> Lazear (2000)<br />

The new contract offered a guarantee at approximately the<br />

former wage: paid W to anyone earned less than W under<br />

the piece rate, but paid the piece rate to all of those whose<br />

composition by the piece- rate formula would have<br />

exceeded W<br />

Theory tells us that:<br />

Effort does not decrease when the firm switches, and as<br />

long as there are some high ability workers, average effort<br />

increases<br />

A sufficient condition for the range of worker ability and<br />

output to rise after the switch is that some workers choose<br />

to work enough to be in the piece- rate range (variability of<br />

output is expected to rise)<br />

Data: information on approx. 3,000 workers producing before<br />

and after the switch in contracts, productivity: average<br />

number of units installed by a given worker during a given<br />

month<br />

Results:<br />

Performance Pay and Productivity <strong>–</strong> Lazear (2000)<br />

Discussion<br />

Results<br />

1. 44% gain in productivity when switch to piece rates<br />

2. Approximately half of the increase in productivity reflects<br />

an incentive effect<br />

3. Sorting accounts for the rest (new workers hired after the<br />

switch are more productive)<br />

4. Learning is important<br />

5. There is no Hawthorne effect (ANY change is likely to<br />

bring short term gains in productivity)<br />

6. Unlikely that the effect is spurious (rolled out<br />

geographically)<br />

7. Also wages rise 7%, so both capital and labor better off<br />

(not necessarily the case according to theory)!<br />

Output easily measured, quality problems readily detected<br />

and blame is assignable few similar workplaces<br />

If work is multi- tasking very expensive to provide explicit<br />

incentives for all tasks and if you give incentives only for<br />

some tasks people are going to do just that!<br />

People might start manilupating their performance<br />

measures (Oyer, 1998)<br />

Even worse workers might start sabotaging their coworkers<br />

(Garicano, Palacios- Huerta 05)<br />

Reputation and creating a “culture”<br />

OUTLINE<br />

1. Performance Pay and Productivity <strong>–</strong> Lazear (2000)<br />

2. IT, Workplace organization and the demand for Skilled<br />

Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan, Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

3. Measuring and Explaining Management Practices across<br />

firms and countries <strong>–</strong> Bloom and Van Reenen (2007)<br />

IT, Workplace organization and Skilled Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan,<br />

Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

Key concept: complementarity<br />

Two choice variables are complements when doing one of<br />

them increases the returns to doing the other<br />

Neither the investments nor the organizational changes might<br />

be worthwhile on their own, but together they have a huge<br />

positive effect on performance<br />

Background: Skill- biased technical change means that<br />

technical progress shifts demand towards more highly<br />

skilled workers relative to less skilled<br />

Not all technological revolutions were skilled biased, IT is!<br />

BBH question: How information technology is used in<br />

production?<br />

2

IT, Workplace organization and Skilled Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan,<br />

Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

BBH: “Firms do not simply plug in computers or<br />

telecommunications equipment and achieve service quality or<br />

efficiency gains. Instead they go through a process of<br />

organizational redesign and make substantial changes to their<br />

product and service mix. This raises the possibility that<br />

computers affect labor demand not only directly, as has been<br />

previously studied, but indirectly through other firm-level<br />

changes.”<br />

In other words, to realise the IT benefits firms also need to<br />

invest in changes in organization practices and changes in<br />

products and services taken together<br />

IT, Workplace organization and Skilled Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan,<br />

Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

Declines in IT prices increase adoption and use of IT <br />

increases the economic attractiveness of complementary<br />

investments in work organization and product & service<br />

innovations further increasing demand for IT<br />

Individually and collectively, these three innovations increase<br />

the relative demand for skilled labor<br />

Data:<br />

Panel of IT capital and mix over 1987- 1994<br />

Production function inputs and outputs over 1987- 1994<br />

Cross section survey of organization practices and labor force<br />

characteristics<br />

Approx. 300 large US firms<br />

IT, Workplace organization and Skilled Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan,<br />

Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

Two empirical specifications. The short run input choice<br />

function:<br />

Qcit = f ( Qc′<br />

it<br />

, controls)<br />

where Q cit are firms’ choices that vary more easily as a function<br />

of the others c’ which are fixed or quasi- fixed at the firm<br />

level. Controls: firm size, industry, production process<br />

proxies<br />

They also estimate production functions of the form:<br />

( S − M ) f ( L , K , Q controls)<br />

log =<br />

it it<br />

it it cit;<br />

Dependent: Log (value added), plus interactions to capture<br />

complementarities<br />

IT, Workplace organization and Skilled Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan,<br />

Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

Results:<br />

Evidence of complementarities, but also data limitations<br />

A firm high on all three axes (human capital, IT and work<br />

organization) has a 7% increase in productivity to a firm that<br />

is at the mean on all three, over and above the direct effect<br />

of higher IT capital<br />

Even more interestingly, when the authors changed the mix<br />

(high- low- high, etc), predicted productivity falls to worse<br />

than mean in all cases<br />

Low- low- low is exceptional as it has the same predicted<br />

productivity as the mean<br />

“Old style” firms, internal consistency, “coherent<br />

combination”<br />

OUTLINE<br />

1. Performance Pay and Productivity <strong>–</strong> Lazear (2000)<br />

2. IT, Workplace organization and the demand for Skilled<br />

Labor <strong>–</strong> Bresnahan, Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2002)<br />

3. Measuring and Explaining Management Practices<br />

across firms and countries <strong>–</strong> Bloom and Van Reenen<br />

(2007)<br />

Measuring and Explaining Management Practices across<br />

firms and countries <strong>–</strong> Bloom and Van Reenen (2007)<br />

Large persistent productivity spread across firms and<br />

countries<br />

People typically claim this is due to differences in<br />

“management”<br />

But what is the role of management?<br />

And why does it vary so much across firms and countries?<br />

3

STEPS TO TRY TO MEASURE MANAGEMENT<br />

1) Developing management practice scoring<br />

• Scorecard for 18 monitoring, targets and incentives practices<br />

• 45 minute phone interview of (manufacturing plant) managers<br />

2) Obtaining unbiased responses<br />

• “Double- blind”<br />

• Interviewers do not know company performance<br />

• Managers are not informed (in advance) they are scored<br />

3) Getting firms to participate in the interview<br />

• Introduced as “Lean- manufacturing” interview, no financials<br />

• Endorsement of Bundesbank ,UK Treasury, Banque de France<br />

• Run by 10 MBAs (loud, assertive & business experience)<br />

MONITORING - i.e. “HOW IS PERFORMANCE TRACKED?”<br />

Score<br />

(1): Measures<br />

tracked do not<br />

indicate directly<br />

if overall<br />

business<br />

objectives are<br />

being met.<br />

Certain<br />

processes aren’t<br />

tracked at all<br />

(3): Most key<br />

performance<br />

indicators<br />

are tracked<br />

formally.<br />

Tracking is<br />

overseen by<br />

senior<br />

management<br />

(5): Performance is<br />

continuously<br />

tracked and<br />

communicated,<br />

both formally and<br />

informally, to all<br />

staff using a range<br />

of visual<br />

management tools<br />

Note: All 18 dimensions and over 50 examples in Bloom & VanReenen (2006)<br />

MANAGEMENT SURVEY SAMPLE<br />

• US (290), UK, France and Germany (≈150 each)<br />

• Medium sized manufacturers (100 - 10,000 employees,<br />

median ≈ 600)<br />

• Medium sized because firm practices more homogeneous<br />

• Manufacturing as easier to measure productivity<br />

• Obtained 54% coverage rate from sampling frame<br />

• Response rates uncorrelated with performance measures<br />

INTERVAL VALIDATION OF THE SCORING<br />

• Re- interviewed 64 firms with different interviewers and managers<br />

Firm average scores (over 18 question)<br />

2 nd interview<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

`<br />

2<br />

• Firm- level average<br />

correlation of 0.759<br />

1<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

1 st interview<br />

EXTERNAL VALIDATION OF THE SCORING<br />

Performance<br />

measure<br />

country c<br />

c<br />

c c<br />

c c c c c<br />

y c c<br />

it<br />

= βMNGi<br />

+ α llit<br />

+ α kkit<br />

+ α mmit<br />

+ γ ' xit<br />

+<br />

management<br />

ln(capital) other controls<br />

(average z- scores) ln(labor) ln(materials)<br />

• Use up to 11 years of accounting data for 1994- 2004<br />

• Note <strong>–</strong> not a causal estimation, only an association<br />

u<br />

c<br />

it<br />

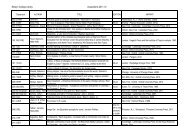

EXTERNAL VALIDATION: PRODUCTIVITY & PROFIT<br />

Dependent<br />

variable<br />

Sales<br />

(in Ln)<br />

Sales<br />

(in Ln)<br />

Sales<br />

(in Ln)<br />

ROCE<br />

Tobin Q<br />

(in Ln)<br />

Sales<br />

growth<br />

1<br />

Management i<br />

Estimation OLS OLS OLS OLS OLS OLS Probit<br />

Firms<br />

All All All All Quoted All All<br />

0.085 0.034<br />

0.042 2.469<br />

0.250 0.018<br />

(0.025) (0.011)<br />

(0.012) (0.688)<br />

(0.075)- (0.006)<br />

-0.200<br />

[0.026]<br />

Controls 1 No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes<br />

Ln(Labor) it<br />

0.999 0.539<br />

0.540 2.172<br />

0.209 -0.022<br />

(0.014) (0.021)<br />

(0.021) (1.202)<br />

(0.109) (0.011)<br />

0.233<br />

[0.045]<br />

0.103<br />

0.104 -0.148<br />

-0.029 0.024 -0.158<br />

Ln(Capital) it (0.013)<br />

(0.013) (0.899)<br />

(0.086) (0.008) [0.045]<br />

Ln(Materials) it<br />

0.362<br />

0.354 -0.439<br />

0.130 -0.010 -0.084<br />

(0.020)<br />

(0.020) (0.723)<br />

(0.050) (0.007) [0.231]<br />

Noise controls No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes<br />

Observations 6,267 5,350 5,350 5,089 2,635 4,777 709<br />

Firms<br />

732 709 709 690 374 702 709<br />

1<br />

Includes country, year, SIC3 industry, skills, hours, firm-age, and public/private<br />

Robust S.E.s in ( ) below. For probit p-values in [ ] below<br />

Exit<br />

4

FIRM LEVEL AVERAGE MANAGEMENT SCORES<br />

Density<br />

Density<br />

.6 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1 1.2 0 .2 .4 .8 1 1.2<br />

France n=137 Germany<br />

n=157<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

UK<br />

n=154<br />

Density<br />

Density<br />

.6 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1 1.2 0 .2 .4 .8 1 1.2<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

US<br />

n=290<br />

COUNTRY LEVEL MANAGEMENT SCORES*<br />

US<br />

Germany<br />

France<br />

UK<br />

3.14<br />

3.07<br />

3.35<br />

3.31<br />

Bad manufacturing management - a UK tradition?<br />

Typical UK managers?<br />

“Efficient management is the single most significant factor<br />

in the American productivity advantage”<br />

[Marshall Plan Anglo- American productivity mission, 1947]<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

Measuring and Explaining Management Practices across<br />

firms and countries <strong>–</strong> Bloom and Van Reenen (2007)<br />

Demonstrate that two factors appear significant:<br />

Production market competition <strong>–</strong> positive effect<br />

Family managed firms <strong>–</strong> negative effect<br />

Family firm ownership but not management is fine<br />

Family ownership and management problematic, particularly<br />

under primo geniture CEO succession<br />

Competition and family- management important, explains<br />

about 50% of firm- level management tail; and between 1/3 to<br />

2/3 of US- Europe management gap:<br />

<strong>–</strong> Europe has lower levels of competition<br />

<strong>–</strong> UK & France also many more primo geniture family firms<br />

due to Norman legal origin & tradition<br />

Management Practices across Europe, the US and Asia <strong>–</strong><br />

Bloom, Genakos, Sadun and Van Reenen (2008)<br />

Extend this methodology to 13 different countries across<br />

Europe, US and Asia<br />

Interview more than 4,000 firms<br />

Data also on their production function inputs<br />

Is there a role for management practices? Historically there<br />

was no international management data<br />

LINKED TO PERFORMANCE IN ALL THE<br />

COUNTRIES (NOT JUST ANGLO-SAXON ONES)<br />

Labor Productivity<br />

Labor Productivity<br />

/em ployee (in logs) - b asi c labor p roductivity m easure - ra w num bers<br />

4 5 6 7<br />

/em ployee (in logs) - b asi c labor p roductivity m easure - ra w num bers<br />

3 4 5 6 7<br />

US & UK<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

Our management score - average across 18 questions<br />

Management<br />

Greece, Portugal & Italy<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

Our management score - average across 18 questions<br />

Management<br />

Labor Productivity<br />

/em ployee (in lo gs) - basic la bor prod uctivity m e asure - raw num bers<br />

2 4 6 8<br />

/em ployee (in logs) - b asi c labor p roductivity m easure - ra w num bers<br />

2 4 6 8<br />

Japan & China<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

Our management score - average across 18 questions<br />

France, Germany, Sweden & Poland<br />

Labor Productivity<br />

Management<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

Our management score - average across 18 questions<br />

Management<br />

HETEROGENEITY IN MANAGEMENT SCORES BY<br />

COUNTRY<br />

Average management score, by country<br />

U.S.<br />

Germany<br />

Sweden<br />

Japan<br />

Italy<br />

UK<br />

France<br />

Poland<br />

Portugal<br />

Greece<br />

China<br />

India<br />

2.73<br />

2.64<br />

2.63<br />

2.62<br />

3.00<br />

3.00<br />

2.99<br />

2.88<br />

3.30<br />

3.17<br />

3.15<br />

3.15<br />

3 statistically distinct<br />

groups appear<br />

<strong>–</strong> U.S., Germany,<br />

Sweden and<br />

Japan<br />

<strong>–</strong> Italy, U.K.,<br />

France, and<br />

Poland<br />

<strong>–</strong> Portugal,<br />

Greece, China<br />

and India<br />

5

BUT THE US IS NOT BEST AT EVERYTHING - THERE<br />

ARE NATIONAL STRENGTHS & WEAKNESSES<br />

Greece<br />

Portugal<br />

India<br />

China<br />

Italy<br />

France<br />

Sweden<br />

Poland<br />

Japan<br />

UK<br />

Germany<br />

US<br />

People management<br />

Operations management<br />

0 1 2 3 4<br />

The US is world<br />

leading in people<br />

management, but<br />

Germany, Sweden<br />

and Japan are<br />

better on average<br />

at operations<br />

management<br />

MULTINATIONALS ARE WELL RUN EVERYWHERE<br />

Greece<br />

India<br />

Portugal<br />

China<br />

Poland<br />

France<br />

UK<br />

Italy<br />

Germany<br />

Sweden<br />

Japan<br />

US<br />

Multinationals<br />

Domestic firms<br />

Multinational<br />

presence also<br />

appears to be<br />

linked with<br />

better<br />

management of<br />

domestic firms<br />

0 1 2 3 4<br />

THE AVERAGE MANAGER ALSO THINKS HIS FIRMS<br />

MANAGEMENT IS WELL ABOVE AVERAGE<br />

Share D en sity of firms<br />

0 .1 .2 .3<br />

“Worst<br />

Practice”<br />

Response to the Question<br />

“Excluding yourself, how would you<br />

rate your company’s management<br />

from 1 to 10, one being the worst<br />

and ten being the best?”<br />

“Average”<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 0<br />

Management self-score<br />

“Best<br />

Practice”<br />

AND THIS OVER-SCORING OCCURS IN EVERY<br />

COUNTRY IN OUR SAMPLE<br />

China<br />

Greece<br />

India<br />

Portugal<br />

Poland<br />

Italy<br />

France<br />

UK<br />

Japan<br />

Sweden<br />

Germany<br />

US<br />

0 1 2 3 4<br />

Actual score<br />

Self score*<br />

* Divided by 2 to normalize to a similar scale<br />

SUMMARY<br />

1. Innovative survey tool to collect management practice data<br />

for over 4000 firms across 13 countries<br />

2. Better management practices are strongly associated with<br />

superior firm performance<br />

3. Significant within country variation in management practices<br />

4. Key factors that can potentially explain this heterogeneity<br />

include: competition, type of ownership, MNE’s, skills,<br />

regulation and education.<br />

<strong>Contracts</strong>, <strong>Incentives</strong> and Organization Structure:<br />

References<br />

* Lazear, E. (2000) “Performance Pay and Productivity”,<br />

American Economic Review, 90:1346-61.<br />

* Bresnahan, T., Brynjolfsson, E. and L. Hitt (2002) “Information<br />

Technology, Workplace Organizationa dn the Demand for Skilled<br />

Labor: Firm-level evidence”, Quarterly Journal of Economics,<br />

February 339-376.<br />

* Bloom, N. and Van Reenen, J. (2007) “Measuring and<br />

Explaining Management Practices across firms and countries”,<br />

Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 1351-1408.<br />

It was hard work but…?<br />

6