Next Level Bassist Left Hand

Summer 2014 edition of Next Level Bassist. Left hand techniques and exercises by Nicholas Walker, Jordan Anderson, Paul Kowert. Section Spotlight on Cleveland Orchestra. Up and Comers Tim Dilenschneider and Jordan Morton

Summer 2014 edition of Next Level Bassist. Left hand techniques and exercises by Nicholas Walker, Jordan Anderson, Paul Kowert. Section Spotlight on Cleveland Orchestra. Up and Comers Tim Dilenschneider and Jordan Morton

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

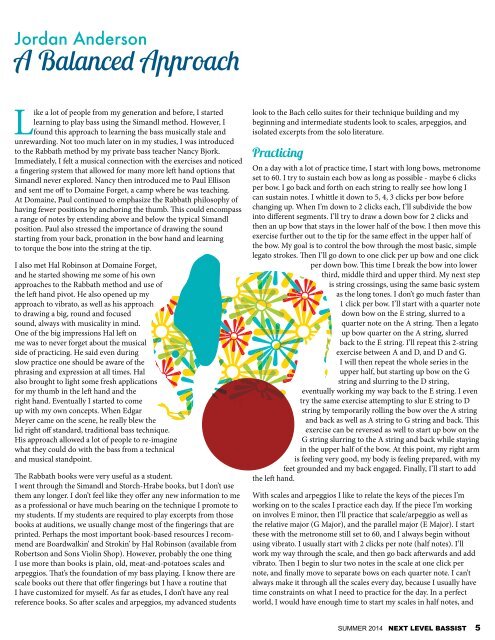

Jordan Anderson<br />

A Balanced Approach<br />

Like a lot of people from my generation and before, I started<br />

learning to play bass using the Simandl method. However, I<br />

found this approach to learning the bass musically stale and<br />

unrewarding. Not too much later on in my studies, I was introduced<br />

to the Rabbath method by my private bass teacher Nancy Bjork.<br />

Immediately, I felt a musical connection with the exercises and noticed<br />

a fingering system that allowed for many more left hand options that<br />

Simandl never explored. Nancy then introduced me to Paul Ellison<br />

and sent me off to Domaine Forget, a camp where he was teaching.<br />

At Domaine, Paul continued to emphasize the Rabbath philosophy of<br />

having fewer positions by anchoring the thumb. This could encompass<br />

a range of notes by extending above and below the typical Simandl<br />

position. Paul also stressed the importance of drawing the sound<br />

starting from your back, pronation in the bow hand and learning<br />

to torque the bow into the string at the tip.<br />

I also met Hal Robinson at Domaine Forget,<br />

and he started showing me some of his own<br />

approaches to the Rabbath method and use of<br />

the left hand pivot. He also opened up my<br />

approach to vibrato, as well as his approach<br />

to drawing a big, round and focused<br />

sound, always with musicality in mind.<br />

One of the big impressions Hal left on<br />

me was to never forget about the musical<br />

side of practicing. He said even during<br />

slow practice one should be aware of the<br />

phrasing and expression at all times. Hal<br />

also brought to light some fresh applications<br />

for my thumb in the left hand and the<br />

right hand. Eventually I started to come<br />

up with my own concepts. When Edgar<br />

Meyer came on the scene, he really blew the<br />

lid right off standard, traditional bass technique.<br />

His approach allowed a lot of people to re-imagine<br />

what they could do with the bass from a technical<br />

and musical standpoint.<br />

The Rabbath books were very useful as a student.<br />

I went through the Simandl and Storch-Hrabe books, but I don’t use<br />

them any longer. I don’t feel like they offer any new information to me<br />

as a professional or have much bearing on the technique I promote to<br />

my students. If my students are required to play excerpts from those<br />

books at auditions, we usually change most of the fingerings that are<br />

printed. Perhaps the most important book-based resources I recommend<br />

are Boardwalkin’ and Strokin’ by Hal Robinson (available from<br />

Robertson and Sons Violin Shop). However, probably the one thing<br />

I use more than books is plain, old, meat-and-potatoes scales and<br />

arpeggios. That’s the foundation of my bass playing. I know there are<br />

scale books out there that offer fingerings but I have a routine that<br />

I have customized for myself. As far as etudes, I don’t have any real<br />

reference books. So after scales and arpeggios, my advanced students<br />

look to the Bach cello suites for their technique building and my<br />

beginning and intermediate students look to scales, arpeggios, and<br />

isolated excerpts from the solo literature.<br />

Practicing<br />

On a day with a lot of practice time, I start with long bows, metronome<br />

set to 60. I try to sustain each bow as long as possible - maybe 6 clicks<br />

per bow. I go back and forth on each string to really see how long I<br />

can sustain notes. I whittle it down to 5, 4, 3 clicks per bow before<br />

changing up. When I’m down to 2 clicks each, I’ll subdivide the bow<br />

into different segments. I’ll try to draw a down bow for 2 clicks and<br />

then an up bow that stays in the lower half of the bow. I then move this<br />

exercise further out to the tip for the same effect in the upper half of<br />

the bow. My goal is to control the bow through the most basic, simple<br />

legato strokes. Then I’ll go down to one click per up bow and one click<br />

per down bow. This time I break the bow into lower<br />

third, middle third and upper third. My next step<br />

is string crossings, using the same basic system<br />

as the long tones. I don’t go much faster than<br />

1 click per bow. I’ll start with a quarter note<br />

down bow on the E string, slurred to a<br />

quarter note on the A string. Then a legato<br />

up bow quarter on the A string, slurred<br />

back to the E string. I’ll repeat this 2-string<br />

exercise between A and D, and D and G.<br />

I will then repeat the whole series in the<br />

upper half, but starting up bow on the G<br />

string and slurring to the D string,<br />

eventually working my way back to the E string. I even<br />

try the same exercise attempting to slur E string to D<br />

string by temporarily rolling the bow over the A string<br />

and back as well as A string to G string and back. This<br />

exercise can be reversed as well to start up bow on the<br />

G string slurring to the A string and back while staying<br />

in the upper half of the bow. At this point, my right arm<br />

is feeling very good, my body is feeling prepared, with my<br />

feet grounded and my back engaged. Finally, I’ll start to add<br />

the left hand.<br />

With scales and arpeggios I like to relate the keys of the pieces I’m<br />

working on to the scales I practice each day. If the piece I’m working<br />

on involves E minor, then I’ll practice that scale/arpeggio as well as<br />

the relative major (G Major), and the parallel major (E Major). I start<br />

these with the metronome still set to 60, and I always begin without<br />

using vibrato. I usually start with 2 clicks per note (half notes). I’ll<br />

work my way through the scale, and then go back afterwards and add<br />

vibrato. Then I begin to slur two notes in the scale at one click per<br />

note, and finally move to separate bows on each quarter note. I can’t<br />

always make it through all the scales every day, because I usually have<br />

time constraints on what I need to practice for the day. In a perfect<br />

world, I would have enough time to start my scales in half notes, and<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST<br />

5