Incongruent effects of sad mood on self- conception ... - ResearchGate

Incongruent effects of sad mood on self- conception ... - ResearchGate

Incongruent effects of sad mood on self- conception ... - ResearchGate

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

European Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Social Psychology, Vol. 24, 161–172 (1994)<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Inc<strong>on</strong>gruent</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>self</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong><br />

valence: it's a matter <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time<br />

CONSTANTINE SEDIKIDES<br />

The University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> North Carolina at Chapel Hill<br />

Abstract<br />

A new hypothesis is proposed to account for the relati<strong>on</strong> between <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and <strong>self</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong><br />

valence, the first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' hypothesis. According to<br />

this hypothesis, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> initially influences the valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> open-ended <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

in a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruent fashi<strong>on</strong>, but after a short period <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s become<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruent. Subjects were placed into a <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>, neutral, or happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> state, and<br />

were subsequently asked to freely describe themselves in writing. The results were<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sistent with the hypothesis. Sad <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> affected the valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

in a c<strong>on</strong>gruent manner, but affected the valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

in an inc<strong>on</strong>gruent manner. That is, with the passage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> led to<br />

increasingly positive <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s (i.e. equally positive as neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> did).<br />

Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the findings are discussed.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Self-percepti<strong>on</strong> processes occur <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten times under the influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> states. How do<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> states affect the ways in which people judge, remember, or describe them-selves?<br />

More specifically, how does <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> (as opposed to neutral and happy) <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> affect the<br />

valence (i.e. negativity–positivity) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> judged, remembered, or described <strong>self</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s?<br />

Two broad empirical generalizati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fer some guidance to this<br />

questi<strong>on</strong>; the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis and the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis.<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis<br />

According to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> colours <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

negatively. A <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>gruency effect is predicted by several theoretical models.<br />

I thank Brad C<strong>on</strong>nell, Joseph Forgas, and three an<strong>on</strong>ymous reviewers for c<strong>on</strong>structive comments <strong>on</strong><br />

earlier drafts. I also acknowledge the assistance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Bryan Doyle, Rick Navarre, Jodi Rapkin, and Terrie<br />

Welhouse with data collecti<strong>on</strong> and coding. Corresp<strong>on</strong>dence c<strong>on</strong>cerning this article should be addressed to<br />

C<strong>on</strong>stantine Sedikides, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Psychology, The University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB<br />

# 3270, Davie Hall, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3270, U.S.A.<br />

0046-2772/94/010161–12$11.00 Received 27 October 1992<br />

© 1994 by John Wiley & S<strong>on</strong>s, Ltd. Accepted 10 June 1993

162 C. Sedikides<br />

These models differ in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the postulated mechanism through which the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

c<strong>on</strong>gruency effect is obtained. The models can be classified broadly as cognitive or<br />

motivati<strong>on</strong>al. The most well-known and empirically supported''' cognitive models are<br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-priming or network models (Bower, 1981, 1991; Clark and Isen, 1982; Isen<br />

1984). According to these models, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> primes and thus renders accessible in<br />

memory <strong>self</strong>-relevant informati<strong>on</strong> that is valuatively c<strong>on</strong>gruent with the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> (i.e.<br />

negative). This informati<strong>on</strong>, in turn, forms the basis for subsequent (and similarlyvalenced)<br />

retrieval or judgments <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s. Motivati<strong>on</strong>al models (Mischel,<br />

Coates and Rask<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f, 1968; Mischel, Ebbesen and Zeiss, 1976) capitalize <strong>on</strong> the<br />

assumpti<strong>on</strong> that humans are motivated to maintain their current affective state. Mood<br />

induces a global sense <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>ness that humans maintain through judging or retrieving<br />

<strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s in a valuatively c<strong>on</strong>gruent manner.<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis<br />

The relati<strong>on</strong> between <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> valence can also be stated in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis 3 (Clark and Isen, 1982; Forgas, 1991; Isen, 1984).<br />

This motivati<strong>on</strong>ally-oriented formulati<strong>on</strong> proposes that people in a <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> will<br />

attempt to exit their aversive <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> state through regulatory strategies, such as positive<br />

thinking, <strong>self</strong>-reward, rati<strong>on</strong>alizati<strong>on</strong>, or external distracti<strong>on</strong> (Frijda, 1986; Morris and<br />

Reilly, 1987; Scheler, and Carver, 1982). These strategies will result in increased<br />

positivity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Mood <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> valence as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time delay: first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency;<br />

then inc<strong>on</strong>gruency<br />

One potential weakness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tests <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>gruency versus <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inc<strong>on</strong>gruency<br />

hypothesis (see Sedikides (1922a) for a review) is their lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> attenti<strong>on</strong> to time delay.<br />

Dependent measures (e.g. judgments <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-relevant attributes, expectancies about<br />

future own behaviour, autobiographical recall) are typically collected <strong>on</strong>ce, that is,<br />

immediately following the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> procedure. Alterati<strong>on</strong>s in <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong><br />

valence are not typically examined as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time delay.<br />

A serious c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the time delay factor invites new challenges to the form<br />

and empirical testing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency vis-a-vis <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency<br />

' Other cognitive models propose that <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> are either due to the informati<strong>on</strong> embedded in<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> manipulati<strong>on</strong>s (rather than <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> per se) acting as a prime (Riskind, 1983), or to subjects' compliant<br />

and c<strong>on</strong>scious efforts to maintain and even boost their <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Blaney, 1986). However, these models have<br />

not been empirically supported (Parrott, 1991).<br />

s Two other models, the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-as-informati<strong>on</strong> view (Schwarz and Clore, 1988) and the multiprocess<br />

model (Forgas, 1992), are not presented in depth here, because they are tangential to the purposes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this<br />

research. These models predict interactive <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> states and stimulus complexity, and thus<br />

presuppose manipulati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the complexity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the stimulus field, something that the reported research did<br />

not accomplish.<br />

' Two other hypotheses, the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> repair and negative state relief (Carls<strong>on</strong> and Miller, 1987) hypotheses,<br />

make similar predicti<strong>on</strong>s with the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis. Nevertheless, the term <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inc<strong>on</strong>gruency<br />

was preferred. Whereas the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> repair and negative state relief hypotheses propose regulatory<br />

processes for the purpose <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> modifying the displeasing <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis proposes<br />

regulatory processes that aim at altering either the <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> or the negativ e <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s that predominate<br />

at the time (See secti<strong>on</strong> Mood <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> valence as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time delay: first<br />

c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, Inc<strong>on</strong>gruency).

First, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency 163<br />

c<strong>on</strong>troversy. Imagine a case where subjects are induced into a <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> state and<br />

are subsequently asked to openly describe themselves over a relatively extended time<br />

period. I propose that, in this case, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> is likely to exert initially c<strong>on</strong>gruent<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> valence, followed by inc<strong>on</strong>gruent <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g>. This scenario<br />

will be labelled the `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' hypothesis.<br />

How could a `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' scenario be accounted for? At<br />

least two explanati<strong>on</strong>s are plausible. One explanati<strong>on</strong> asserts that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> primes<br />

negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s, which figure in subjects' negative overt <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

However, with the passage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time, subjects become aware <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-induced bias in<br />

their <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s, and engage in <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-regulati<strong>on</strong>. Mood-regulati<strong>on</strong> entails<br />

subjects attempting to terminate their unpleasant <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> state and entering into a<br />

happier <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> by `resetting' the evidential base <strong>on</strong> which the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s were<br />

based, leading to an increase in the positivity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s. Alternatively, with<br />

the passage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time subjects may engage in <strong>self</strong>-regulati<strong>on</strong>. The negative <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

will reach a `critical mass', after which subjects become motivated to<br />

pursue a cognitive c<strong>on</strong>trast strategy (reminiscent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Martin, 1986), namely to access<br />

<strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s that c<strong>on</strong>trast the previously accessed <strong>on</strong>es. This strategy will be<br />

fuelled by the <strong>self</strong>-enhancement motive (Sedikides, 1993a; Taylor and Brown, 1988)<br />

and will result in a switch-over from negative to positive <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Another explanati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' scenario states<br />

that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects become overwhelmed and energy depleted due to the shocking<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Sedikides, 1992, p. 278) and are c<strong>on</strong>sequently unable in the<br />

short run to engage in cognitive strategies (e.g. <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> regulati<strong>on</strong> or <strong>self</strong>-regulati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

that would alter their <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Hence, their <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s are inevitably at the mercy<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the valuative influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and thus <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>gruent. However, as time goes<br />

by, subjects will overcome their initial shock, regain their energy, and manage to cope<br />

with the situati<strong>on</strong> by becoming involved in either <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-management or <strong>self</strong>regulatory<br />

strategies. The result will be increasingly positive <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

In summary, the `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' hypothesis proposes that<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects will begin describing themselves in a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruent manner,<br />

but will progressively describe themselves as positively as neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects do<br />

(weak renditi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the hypothesis) or even as happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects do (str<strong>on</strong>g<br />

renditi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the hypothesis). Thus, there will be more positive <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s in the<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects' protocols than in the first half. The `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then,<br />

inc<strong>on</strong>gruency ' hypothesis was tested in the present experiment.<br />

PILOT STUDY<br />

It is crucial for the purposes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this investigati<strong>on</strong> to establish the time interval in<br />

which the induced <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> states are maintained, so that a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> decay explanati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the obtained findings can be ruled out. This time interval should then be allotted to<br />

subjects for the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> task. I c<strong>on</strong>ducted a pilot study to accomplish this<br />

objective.<br />

The pilot study involved 48 University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wisc<strong>on</strong>sin introductory psychology students<br />

who participated in exchange for extra course credit. Subjects were first induced<br />

into a state <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>, neutral, or happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> (for more details, see secti<strong>on</strong>s The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

inducti<strong>on</strong> task and Procedure). Next, subjects completed two assignments. Specifi-

164 C. Sedikides<br />

cally, they were asked to locate the names <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> famous psychologists hidden in a letter<br />

matrix for 4 min, and to write down as many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the United States as possible for<br />

another 2 min. Half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the subjects filled out three 9-point <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-assessing scales (<str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

versus happy, depressed versus elated, gloomy versus c<strong>on</strong>tent) up<strong>on</strong> completi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

first assignment (i.e. 4 min after the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> procedure), and the other half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the subjects filled out the three scales up<strong>on</strong> completi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the sec<strong>on</strong>d assignment (i.e.<br />

6 min after the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> procedure).<br />

Mood was sustained for 4 min following its inducti<strong>on</strong>, F(2,21) = 8.28, p < 0.002.<br />

Orthog<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>trasts revealed that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 4.54) reported feeling<br />

significantly <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>der than either neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 5.92), p < 0.008, or happy<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects (M = 6.38), p < 0.001. Neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects reported feeling less happy<br />

than happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, but not significantly so, p < 0.34. Mood was also sustained<br />

for 6 min after its inducti<strong>on</strong>, F(2,21) = 4.93,p < 0.018. Orthog<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>trasts showed<br />

that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 5.00) reported feeling <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>der than neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects<br />

(M = 5.71), although n<strong>on</strong>-significantly so (p < 0.15), and <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>der than happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects (M = 6.50), p < 0.005. Neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects reported feeling less happy than<br />

happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, but not significantly so, p < 0.11. Moreover, the interacti<strong>on</strong><br />

between <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and time delay (4 min versus 6 min) was not significant, F(2,42) =<br />

0.50, p < 0.61. The n<strong>on</strong>-significance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the interacti<strong>on</strong> is anticipated by the claim that<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> was sustained for 6 min following its inducti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

METHOD<br />

Subjects and experimental design<br />

Subjects were 180 University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wisc<strong>on</strong>sin undergraduates, who received extra introductory<br />

psychology credit for their participati<strong>on</strong>. Subjects were run individually and<br />

assigned randomly to the experimental c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. The experiment involved a 3<br />

(<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>, neutral, happy) x2 (rating order: valence ratings first, importance ratings<br />

first) x2 (<strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> order: <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> valence ratings for first half versus<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>d half) mixed-design, with the last factor being within-subjects.<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> task<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> task involved a two-step guided imagery procedure. In each<br />

step, subjects were asked to imagine a <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>, neutral, or happy event for 2 min, and<br />

then write about this event for 3 min. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> events involved imagining a friend<br />

being burned in a fire and dying. The neutral events involved imagining a friend<br />

watching the evening news <strong>on</strong> televisi<strong>on</strong> and riding a bus. Finally, the happy events<br />

involved imagining a friend winning a free cruise to the Carribbean islands and<br />

winning $1 000 000 in the state lottery. A comm<strong>on</strong> thread in all <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inducing events<br />

was that attenti<strong>on</strong>al focus was both other-directed (thinking about another pers<strong>on</strong><br />

rather than the <strong>self</strong> as the target <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the event) and outward (thinking about another<br />

pers<strong>on</strong>'s rather than <strong>on</strong>e's own thoughts and feelings). (See Carls<strong>on</strong> and Miller (1987)<br />

for the relevant distincti<strong>on</strong>.) This precauti<strong>on</strong> was deemed necessary in light <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> findings<br />

that <strong>self</strong>-directed and inward attenti<strong>on</strong>al focus is likely to elicit <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> in indivi-

First, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency 165<br />

duals possessing chr<strong>on</strong>ically negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s (Sedikides, 1992b). The pre -<br />

cauti<strong>on</strong> reduced the possibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>founding the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> with the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> task per se (i.e. attenti<strong>on</strong>al focus <strong>on</strong> the <strong>self</strong>).<br />

Procedure<br />

The procedure was designed to disguise the relati<strong>on</strong> between the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong><br />

task and the dependent measures, because awareness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this relati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects can eliminate, diminish, or alter the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> (e.g. Berkowitz and<br />

Troccolli, 1990; Strack, Schwarz and Gschneidinger, 1985). Two experimenters, a<br />

woman and a man, tested each subject. The experimenters were dressed in different<br />

clothing styles (former versus casual), and used booklets with differently coloured<br />

pages (green versus white). Experimenter A announced to subjects that the study was<br />

c<strong>on</strong>cerned with percepti<strong>on</strong> and proceeded to ask subjects a favour. Experimenter A<br />

introduced experimenter B as a student whose h<strong>on</strong>ours thesis was c<strong>on</strong>cerned with<br />

people's ability for imaginative thinking. Experimenter A asked subjects to d<strong>on</strong>ate<br />

`<strong>on</strong>ly a few minutes' to participating in experimenter B's study. All subjects agreed<br />

to participate. Experimenter B's study was actually the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> task. After<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> was induced, subjects (a) rated the two -step imaginati<strong>on</strong> task for easiness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

imagining (1 =extremely difficult to imagine, 9 =extremely easy to imagine), (b)<br />

indicated how they felt <strong>on</strong> three 9-point scales: <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>–happy, depressed–elated, and<br />

gloomy–c<strong>on</strong>tent (1 anchored `<str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> ' , `depressed ' , and `gloomy', whereas 9 anchored<br />

`happy', `elated' and `c<strong>on</strong>tent'), and (c) rated the two -step imaginati<strong>on</strong> task for easiness<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comprehensi<strong>on</strong> (1 =extremely difficult to comprehend, 9 =extremely easy to<br />

comprehend). Next, experimenter A took over, administered a booklet c<strong>on</strong>taining 40<br />

blank half-pages, and asked subjects to `tell us about your<strong>self</strong>'. Subjects were<br />

instructed to list any <strong>self</strong>-referential thoughts that crossed their mind, to place <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

<strong>on</strong>e <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> per page, and not to turn back to previous pages. Subjects were<br />

allotted 6 min (a time interval that was decided <strong>on</strong> the basis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the pilot study) for<br />

the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> task.<br />

When the allotted 6 min expired, subjects were occupied with three unrelated<br />

assignments for 13 min. The assignments were finding the names <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> favour psychologists<br />

hidden in a letter matrix (5 min), writing down as many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the United States<br />

as possible (3 min), and listing the capitals <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 50 United States (5 min). The<br />

purpose <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this battery <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> assignments was to increase the probability that the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> be dissipated before the impending rating tasks. Next, subjects rated each<br />

<strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> for valence (1 = extremely negative, 9 = extremely positive) and<br />

importance (1 = extremely unimportant, 9 = extremely important). Half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

subjects rated the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s for valence first, whereas the other half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects<br />

rated the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s for importance first. In order to encourage the independence<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the rating tasks, subjects (1) rated the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s in separate booklets<br />

for valence versus importance, and (2) the two rating tasks were separated by 3 min<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> involvement in an unrelated assignment (locating the names <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> past United States<br />

presidents which were scattered in a matrix <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> letters). Next, subjects were verbally<br />

probed fo r suspici<strong>on</strong>. No subject suspected the relati<strong>on</strong> between the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong><br />

task and <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> task. Finally, subjects read two pages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comics, were<br />

thoroughly debriefed, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fered a Hershey's chocolate kiss as a `thanks' gesture<br />

(which proved to b e a fairly potent smile inducer).

166 C. Sedikides<br />

RESULTS<br />

Mood manipulati<strong>on</strong> check<br />

Subjects ' resp<strong>on</strong>ses to the three <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-assessing scales were highly intercorrelated<br />

(Cr<strong>on</strong>bach ' s alpha = 0.77). Resp<strong>on</strong>ses were subsequently averaged and entered in an<br />

analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variance (ANOVA), with <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> as the <strong>on</strong>ly factor. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inducti<strong>on</strong> task<br />

was effective, F(2, 177) = 47.02, p < 0.0001. Orthog<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>trasts (p < 0.0001)<br />

indicated that subjects in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> reported feeling <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>der (M = 4.32)<br />

than subjects in the neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> (M = 5.17), who in turn reported feeling<br />

less happy than subjects in the happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> (M = 6.01). Further-more,<br />

subjects found the three tasks equally easy to imagine, F(2, 177) = 1.57, p < 0.21, and<br />

comprehend, F(2, 177) = 0.91,p < 0.41.<br />

Valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

i<br />

I formed two valence indices (pertaining to the two halves <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s) for<br />

each subject by dividing the sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> valence ratings by the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

These indices were entered in an ANOVA involving <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and rating order as<br />

between-subjects factors, and <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> order as a within-subjects factor.<br />

The `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' formulati<strong>on</strong> predicts a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency<br />

effect in the first half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects' <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s, but a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency<br />

effect in the sec<strong>on</strong>d half. Before going any further, I will state the predicti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency and <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypotheses.<br />

For the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis to be supported, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> should elicit (1)<br />

significantly more negative <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> ratings than neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, (2) significantly<br />

more negative <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> ratings than happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, and (3) significantly more<br />

negative <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> ratings than neutral and happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>s combined. Thus, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> was c<strong>on</strong>trasted against (1) neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, (2) happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, and (3) neutral/happy<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>s combined. On the other hand, for the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis to be<br />

supported, (1) <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> should evoke at least equally valenced (if not more positive)<br />

<strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> ratings as neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, and (2) <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> and happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>s combined<br />

should elicit more positive <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> ratings than neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>. C<strong>on</strong>sequently,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>/happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>s combined were c<strong>on</strong>trasted against neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

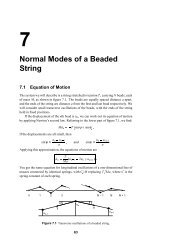

The `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' hypothesis is tested by the interacti<strong>on</strong><br />

between <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> order. This interacti<strong>on</strong> was significant, F(2, 174) =<br />

14.94, p < 0.0001 (Figure 1). To evaluate the interacti<strong>on</strong>, I c<strong>on</strong>ducted separate<br />

ANOVAs for each half. Mood-c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> were apparent in the first half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> main effect F(2, 174) = 62.48, p < 0.0001. Orthog<strong>on</strong>al<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trasts showed that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects described themselves more negatively than<br />

either neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, p < 0.0001, or happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, p < 0.0001.<br />

(Neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects described themselves less positively than happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects,<br />

p < 0.0001.) In additi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects described themselves more negatively<br />

than neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>/happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects combined, p < 0.0001. Finally, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>/happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects did not describe themselves more positively than neutral<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects, p < 0.84, thus failing to support the <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency hypothesis.<br />

Mood c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> were also evident in the sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s,

First, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency167<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> main effect F(2, 174) = 19.31, p < 0.0001. Specifically, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects described<br />

themselves more negatively than happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, p < 0.0001, and less positively<br />

than neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>/happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects combined, p < 0.0001. (Neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects<br />

described themselves less positively than happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, p < 0.0001.) However,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> were also present. First, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects did not describe<br />

themselves more negatively than neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, p < 0.45. Most importantly, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>/happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects described themselves more positively than neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects, p < 0.016. The above results are c<strong>on</strong>sis tent with the weak renditi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the `first,<br />

c<strong>on</strong>gruency; the<br />

Figure 1. Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s: first half versus sec<strong>on</strong>d half<br />

The <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> order main effect was significant, F(1, 174) = 48.46,p < 0.0001, indicating<br />

that the positivity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s was higher in the sec<strong>on</strong>d half (M = 5.93) compared to the<br />

first half (M = 5.48). The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> main effect was also significant, F(2, 174) = 58.42, p < 0.0001,<br />

and c<strong>on</strong>sistent with a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency interpretati<strong>on</strong>. Specifically, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects described<br />

themselves more negatively (M = 5.19) than either neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 5.63), p < 0.0001,<br />

or happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 6.30), p < 0.0001. (Neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects described themselves<br />

less positively than happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, p < 0.0001.) Sad-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects described themselves<br />

more negatively than neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>/happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects combined, p < 0.0001. Finally, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>/happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects did not describe themselves more positively than neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects, p < 0.22.<br />

C<strong>on</strong>sidering alternative hypothesis<br />

The evidence for <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency in the sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s implies that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects became engaged in either <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-regulatory or <strong>self</strong>-regulatory

168 C. Sedikides<br />

strategies (i.e. listing positive <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s). However, an alternative explanati<strong>on</strong><br />

may also be plausible. I will refer to this as the limited sets 4 explanati<strong>on</strong>. According to<br />

this explanati<strong>on</strong>, people have <strong>on</strong>ly a limited set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> negative, neutral, and positive <strong>self</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

In the case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> acted as a prime thus leading them<br />

to access and output negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s. With the passage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time, how-ever,<br />

subjects depleted the limited set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s and subsequently turned<br />

to neutral or positive <strong>on</strong>es.<br />

The limited sets explanati<strong>on</strong> has trouble accounting for the sec<strong>on</strong>d-half findings<br />

pertaining to happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects. According to this explanati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects would deplete their positive <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s at some point<br />

during the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> task and would then turn to neutral or negative <strong>on</strong>es.<br />

However, the <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects remained equally positive in<br />

the sec<strong>on</strong>d half as they were in the first half. Similarly, the <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects remained c<strong>on</strong>sistently neutral in both the first and sec<strong>on</strong>d<br />

halves.<br />

Another versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the limited sets explanati<strong>on</strong>, the limited negative set explanati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

advocates that the <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cept <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> most people (Taylor and Brown, 1988), and<br />

especially college students, is positive. Stated otherwise, the subjects' <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cept<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tains many more positive than negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s. Thus, <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects<br />

exhausted quickly their repertoire <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s (which was primed by<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>) and subsequently turned to their neutral or positive <strong>on</strong>es. In c<strong>on</strong>trast, happy<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects had a relatively large supply <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> positive <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s and output<br />

them c<strong>on</strong>sistently throughout the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> task.<br />

This versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the limited set hypothesis is logically c<strong>on</strong>troversial. Sad-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects generated an average <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 16 <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s (see secti<strong>on</strong> Number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

generated, below). As a rough approximati<strong>on</strong>, the first eight <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

were slightly negative (M = 4.71, see Figure 1), whereas the remaining <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

were neutral or slightly positive (M = 5.66). So, this versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

limited set explanati<strong>on</strong> would ascertain that subjects' slightly negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

were limited to eight, a rather implausible asserti<strong>on</strong>. People can arguably generate<br />

or c<strong>on</strong>struct more than eight slightly negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s. Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, the<br />

limited negative set explanati<strong>on</strong> fails to satisfactorily account for the c<strong>on</strong>sistently<br />

neutral <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects; that is, this explanati<strong>on</strong> would<br />

predict that the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects would turn positive after a<br />

while.<br />

The `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency ' formulati<strong>on</strong> proposes the operati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

motivati<strong>on</strong>al processes (i.e. <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-regulati<strong>on</strong> or <strong>self</strong>-regulati<strong>on</strong>), and correlati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

analyses are c<strong>on</strong>sistent with this proposal. The within-subjects correlati<strong>on</strong> between<br />

valence and importance ratings was significant, r(178) = 0.28, p < 0.0001 5 . How-ever,<br />

between-subjects correlati<strong>on</strong>s manifested a revealing pattern. It was <strong>on</strong>ly under the<br />

influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> that the correlati<strong>on</strong> between valence and importance ratings<br />

' Judgmental latencies can also help distinguish between motivati<strong>on</strong>al and cognitive explanati<strong>on</strong>s (Forgas,<br />

1991). For example, motivati<strong>on</strong>al processing would lead to a reducti<strong>on</strong> in judgmental latencies, whereas<br />

cognitive processing would lead to an increase in judgmental latencies in the sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

'C<strong>on</strong>sistently with this correlati<strong>on</strong>, an analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> covariance (ANCOVAs) <strong>on</strong> the valence ratings using<br />

importance ratings as the covariate yielded a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> main effect, F(2, 173) = 52.94, p < 0.0001. Also, the<br />

separate ANCOVAs for the first and sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s were significant: for the first half, F(2,<br />

173) = 61.20,p < 0.0001; for the sec<strong>on</strong>d half, F(2, 173) = 17.72,p < 0.0001.

First, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency 169<br />

was significant, r(58) = 0.36, p < 0.005 (for neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) = 0.18, p < 0.17; for<br />

happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) = 0.19, p < 0.15). That is, <strong>on</strong>ly <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects generated<br />

either negative and unimportant <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s or positive and important <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Most interestingly, the above correlati<strong>on</strong>al pattern changed as a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong><br />

order. With regard to the first half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s, the correlati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

were not significant: for <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) = -0.02, p < 0.86; for neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) =<br />

-0.01, p < 0.91; and for happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) = 0.10, p < 0.47. However, the picture<br />

was different with regard to the sec<strong>on</strong>d-half correlati<strong>on</strong>s: for <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) = 0.43,<br />

p < 0.001; for neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) = 0.19, p < 0.14; and for happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>, r(58) =<br />

0.29, p < 0.026. The limited sets and limited negative set hypotheses would have<br />

difficulty explaining why both <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects accessed both<br />

positive and important (or negative and unimportant) <strong>self</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s in the sec<strong>on</strong>d<br />

half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> task. In c<strong>on</strong>trast, the motivati<strong>on</strong>ally-based `first,<br />

c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' formulati<strong>on</strong> would postulate that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects<br />

managed their <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> or countered their previously negative <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s by<br />

reaffirming the positivity and importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s, whereas happy<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects maintained their <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> by increasing the importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their positive<br />

<strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

The between-subjects correlati<strong>on</strong>s examined separately for first versus sec<strong>on</strong>d half<br />

refute two other versi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the limited sets explanati<strong>on</strong>. One versi<strong>on</strong> states that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects gave their important negative <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s early in the sequence,<br />

and were c<strong>on</strong>sequently left with unimportant negative and important positive <strong>self</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

for the sec<strong>on</strong>d half. Another versi<strong>on</strong> states that neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and happy<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects listed their important positive <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s earlier in the sequence,<br />

whereas the important positive <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s were delayed by the accessibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

negative thoughts as far as <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects were c<strong>on</strong>cerned. The two versi<strong>on</strong>s are<br />

refuted by the finding that the correlati<strong>on</strong> between valence and importance was not<br />

significant for the first half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all subjects' <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s. Thus, <strong>on</strong> the balance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

probabilities, the `first-c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' formulati<strong>on</strong> appears to fit<br />

best the obtained results.<br />

Importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Does <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> affect the importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s? To explore this questi<strong>on</strong> I<br />

formed two importance indices for each half and each subject by dividing the sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the importance ratings by the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s. I then entered these indices<br />

in an ANOVA involving <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and rating order as between-subjects factors, and <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong><br />

order as a within-subjects factor.<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> main effect was significant, F(2, 174) = 3.21, p < 0.043. Tukey HSD<br />

tests revealed that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects rated their <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s as marginally less<br />

important (M = 5.59) than either neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 5.77), p < 0.07, or<br />

happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 5.76), p < 0.075. Neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects rated their <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

as equally important as happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects, p < 0.99.<br />

However, this pattern <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> results did not hold when valence ratings were covaried<br />

out in an ANCOVA, <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> main effect F(2, 173) = 1.32, p < 0.27. Further, the<br />

interacti<strong>on</strong> involving <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> and <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong> order was not significant, F(2, 174)<br />

= 0.93, p < 0.40. The interacti<strong>on</strong> failed to reach significance even after covarying

170 C. Sedikides<br />

out valence ratings, F(2, 173) = 1.14, p < 0.32. Mood did not appear to have<br />

influenced the importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s independently <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> valence.<br />

Number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s generated<br />

Did <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> affect the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s generated? The <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> main effect<br />

was significant, F(2, 177) = 8.14, p < 0.0001. Tukey HSD tests indicated that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects generated more <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s (M = 16.10) than either neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

subjects (M = 14.05),p < 0.0001, or happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects (M = 14.90),p < 0.049.<br />

The <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s neutral-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects generated did not significantly differ<br />

from the <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s that happy-<str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> subjects generated, p < 0.22. These<br />

results are c<strong>on</strong>sistent with recent findings indicating that <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> (but not neutral or<br />

happy <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>) induces <strong>self</strong>-focused attenti<strong>on</strong> (Sedikides, 1992c; Wood, Saltzberg and<br />

Goldsamt, 1990; for a different view, see Salovey, 1992).<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

Most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> past research examining the c<strong>on</strong>sequences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

autobiographical recall has found <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> (e.g. Berkowitz, 1987,<br />

Experiment 2; Bower, 1981, Experiments 1 and 2; Bullingt<strong>on</strong>, 1990; Mathews and<br />

Bradley, 1983; Natale and Hantas, 1982; Salovey and Singer, 1989, Experiments 2<br />

and 3; Snyder and White, 1982, Experiment 1; Teasdale, Taylor and Fogarty, 1981).<br />

The present investigati<strong>on</strong> is both c<strong>on</strong>sistent and inc<strong>on</strong>sistent with past findings. It is<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sistent because it obtained quite powerful <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g>. It is<br />

inc<strong>on</strong>sistent, because it obtained <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> in the midst <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>c<strong>on</strong>gruency.<br />

Whether <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> affects <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> valence in a c<strong>on</strong>gruent or<br />

inc<strong>on</strong>gruent manner is a matter <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time: initially accessed <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s are coloured<br />

in a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruent fashi<strong>on</strong>, but subsequent <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s tend to be coloured<br />

in a <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruent fashi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Why did this investigati<strong>on</strong> produce <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g>? This investigati<strong>on</strong><br />

differs from past research in at least two ways. First, the investigati<strong>on</strong> examined the<br />

valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s separately from the first half. It is<br />

likely that <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> inc<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> were present in the sec<strong>on</strong>d half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

with regard to past research, but these <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> were obscured due to<br />

collapsing across the two halves. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, the investigati<strong>on</strong> was c<strong>on</strong>cerned with openended<br />

descripti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <strong>self</strong> rather than autobiographical recall. Open-ended <strong>self</strong>descripti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

tap aspects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the present <strong>self</strong>, whereas autobiographical recall taps<br />

aspects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the past <strong>self</strong>. Thus, <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> may affect the present <strong>self</strong> quite differently than<br />

the past <strong>self</strong>. This raises the possibility that the present <strong>self</strong> is represented in memory<br />

differently than the past <strong>self</strong>, a possibility that is worthy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> empirical scrutiny.<br />

In fact, the latter possibility may explain in part the discrepancy between the<br />

present results and results obtained by Parrott and Sabini (1990, Experiments 3 and<br />

4). Subjects in these experiments reported autobiographical memories, with the first<br />

memory being <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruent. At the same time, though, the Parrott and Sabini<br />

experiments differed in several additi<strong>on</strong>al respects form the current investigati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

That is, their experiments assessed three memories (instead <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> open-ended

First, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency 171<br />

<strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s provided in 6 min), induced <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> through a music inducti<strong>on</strong> task<br />

(instead <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a guided imagery task), used unipolar (instead <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bipolar) scales to measure<br />

<strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> valence, and did not include neutral <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Future research ought to<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sider these differences in an effort to rec<strong>on</strong>cile the discrepant results.<br />

The findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the current investigati<strong>on</strong> are seemingly at odds with findings<br />

reported by Sedikides (1993). In that art icle, I obtained <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> for<br />

peripheral <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s, but no <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> whatsoever for central <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

However, in the present investigati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> affected the valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> import -<br />

ant <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s as much as it affected the valence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> unimportant <strong>self</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

How can this inc<strong>on</strong>sistency be resolved? First, I (Sedikides, 1993) operati<strong>on</strong>alized<br />

centrality in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both high pers<strong>on</strong>al importance and high <strong>self</strong>-descriptiveness.<br />

The present experiment was not c<strong>on</strong>cerned with the degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>descriptiveness<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, subjects in the present experiment generated<br />

<strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s that were relatively low in importance. Thus, the present experimental<br />

procedures appear to have evoked mostly peripheral <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

How exactly does <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> impact <strong>on</strong> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> valence? In the Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this article, I stated two forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the `first, c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency ' . The<br />

first form proposed an initial <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-priming effect, followed by regulatory strategies.<br />

The sec<strong>on</strong>d form proposed an initial <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> `shock' effect, also followed by regulatory<br />

strategies. Exploring the plausibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these two forms should be a priority issue for<br />

future research. Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, what is the nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the obtained <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-inc<strong>on</strong>gruency<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g>? Two processes were discussed: <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-regulati<strong>on</strong> and <strong>self</strong>-regula ti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Examinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the relative impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each process or clarificati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the circumstances<br />

under which each is most likely to operate also deserves to be in the agenda <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

researchers in this area.<br />

In c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>, this investigati<strong>on</strong> ' s support for the weak renditi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the `first,<br />

c<strong>on</strong>gruency; then, inc<strong>on</strong>gruency' hypothesis (i.e. <str<strong>on</strong>g>sad</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g> leads to an increase in the<br />

positivity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the sec<strong>on</strong>d-half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>self</strong>-descripti<strong>on</strong>s) poses additi<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>straints <strong>on</strong><br />

previously reported omnipresent <str<strong>on</strong>g>mood</str<strong>on</strong>g>-c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>self</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong><br />

valence (Sedikides, 1992a). Mood-c<strong>on</strong>gruency <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> may not be as general as pre -<br />

viously thought.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Berkowitz, L. (1987). `Mood, <strong>self</strong>-awareness and willingness to help', Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pers<strong>on</strong>ality and<br />

Social Psychology, 52: 1-9.<br />

Berkowitz, L. and Troccolli, B. T. (1990). `Feelings, directi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> attenti<strong>on</strong>, and expressed<br />

evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> others', Cogniti<strong>on</strong> and Emoti<strong>on</strong>, 4: 305-325.<br />

Blaney, P. H. (1986). `Affect and memory: A review', Psychological Bulletin, 99: 229-246.<br />

Bower, G. H. (1981). `Mood and memory', American Psychologist, 36: 129-148.<br />

Bower, G. H. (1991). `Mood c<strong>on</strong>gruity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> social judgments'. In: Forgas, J. P. (Ed.) Emoti<strong>on</strong><br />