Biodiversity Action Plan for the National Cycle Network ... - Sustrans

Biodiversity Action Plan for the National Cycle Network ... - Sustrans

Biodiversity Action Plan for the National Cycle Network ... - Sustrans

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

1st Edition<br />

December 2007

<strong>Sustrans</strong> is <strong>the</strong> UK’s leading sustainable transport charity, working on practical projects so<br />

people choose to travel in ways that benefit <strong>the</strong>ir health and <strong>the</strong> environment.<br />

www.sustrans.org.uk<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> Centre<br />

2 Ca<strong>the</strong>dral Square<br />

Bristol<br />

BS1 5DD<br />

Tel: 0117 926 8893<br />

Registered Charity No. 326550<br />

© <strong>Sustrans</strong> December 2007<br />

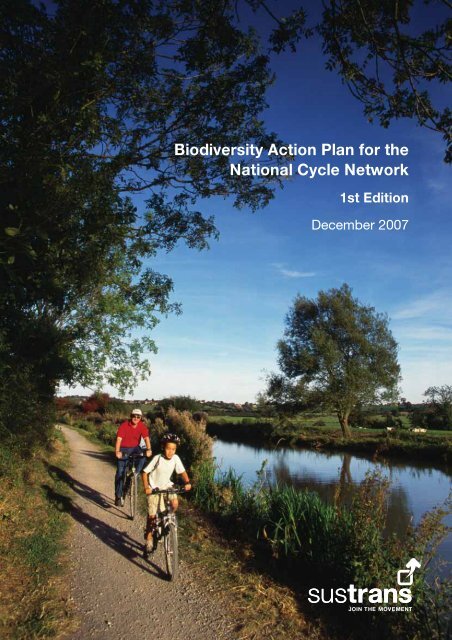

Cover photo: Kennet and Avon Canal, <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> Route 4. Nick Turner/<strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

2

CONTENTS<br />

Executive Summary 6<br />

1. Introduction to biodiversity in <strong>the</strong> UK 7<br />

1.1 Description of biodiversity 7<br />

1.2 The Earth Summit 7<br />

1.3 The UK BAP Process 7<br />

1.4 Local BAPs 7<br />

2. Introduction to <strong>Sustrans</strong> 8<br />

2.1 About <strong>Sustrans</strong> 8<br />

2.2 <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ projects 8<br />

2.3 Flagship project 9<br />

3. <strong>Biodiversity</strong> commitment 12<br />

3.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ aims 12<br />

3.2 Definition of sustainable development 12<br />

3.3 ‘Think globally, act locally’ 12<br />

3.4 Commitment to act locally 12<br />

3.5 The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> 12<br />

4. Key activities and <strong>the</strong>ir impact on biodiversity 12<br />

5. <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ partnerships 14<br />

5.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ partnerships 14<br />

5.2 The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> as an example of partnership 14<br />

6. Objective of <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong><br />

<strong>Network</strong> 16<br />

6.1 Objective 16<br />

6.2 Meeting this objective 16<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

3

7. Links with Local <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s 17<br />

7.1 Local BAPs in <strong>the</strong> UK 17<br />

7.2 Generic action plans 17<br />

7.3 O<strong>the</strong>r species 17<br />

7.4 New species and habitat action plans and monitoring 17<br />

7.5 Local BAP co-ordinators 17<br />

7.6 Influencing <strong>the</strong> NCN 17<br />

8. Monitoring, reviewing and reporting 18<br />

8.1 Reviewing <strong>the</strong> BAP 18<br />

8.2 <strong>Action</strong>s 18<br />

8.3 The first review 18<br />

8.4 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Reporting System (BARS) 18<br />

8.5 About BARS 18<br />

9. Habitat <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s 19<br />

9.1 Hedgerows 19<br />

9.2 Lowland Calcareous Grasslands 20<br />

9.3 Banks and verges 21<br />

10. Species <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s 24<br />

10.1 Birds 24<br />

10.2 Bats Chiroptera 25<br />

10.3 Badger Meles meles 27<br />

10.4 Dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius 28<br />

10.5 Slow worm Anguis fragilis 30<br />

10.6 Great crested newt Triturus cristatus 31<br />

10.7 Invertebrates 32<br />

11. Survey objectives, methods and standards 34<br />

11.1 Ecological surveys 34<br />

11.2 Survey protocols 34<br />

11.3 Survey times 34<br />

11.4 O<strong>the</strong>r species and habitats 34<br />

11.5 Surveying timetable 34<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

4

12. Mitigation and enhancement measures <strong>for</strong> wildlife 35<br />

12.1 Bridge and viaduct maintenance 35<br />

12.2 Bat bricks 35<br />

12.3 Bat and bird boxes 35<br />

12.4 Log and vegetation piles 36<br />

12.5 Lighting 36<br />

12.6 Tree maintenance 36<br />

12.7 Path surfaces 37<br />

12.8 Stone walls 37<br />

13. Controlling native and non-native invasive species 38<br />

13.1 Native species 38<br />

13.1.1 Bramble Rubus fruticosus 38<br />

13.1.2 Common ragwort Senecio jacobaea 38<br />

13.2 Non-native species 38<br />

13.3 Japanese knotweed Fallopia japonica 39<br />

13.4 Himalayan balsam Impatiens balsamifera 40<br />

13.5 Giant hogweed Heracleum mantegazzianum 41<br />

14. Education and understanding 43<br />

14.1 The <strong>Sustrans</strong> website 43<br />

14.2 Interpretation and leaflets 43<br />

14.3 Staff training days 43<br />

14.4 In<strong>for</strong>mation sheets 43<br />

15. References 44<br />

16. Glossary 45<br />

17. Useful contacts and websites 46<br />

Appendix 1 – <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ Ways <strong>for</strong> Wildlife In<strong>for</strong>mation Sheet 49<br />

(published November 2000)<br />

Appendix 2 – Phase 1 and 2 habitat survey methodology 53<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

5

Executive Summary<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> is a term used to describe <strong>the</strong> variety and richness of life on earth. It was a term<br />

first used at <strong>the</strong> Rio Earth Summit in 1992 where over 150 countries pledged to protect and<br />

enhance biological diversity.<br />

The UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Partnership Standing Committee is steering <strong>the</strong> UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong><br />

Partnership, which to date has produced six volumes of national Species <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s<br />

(SAPs) and Habitat <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s (HAPs). The plans set out very clear objectives and targets.<br />

For this process to work effectively it has to be implemented at different levels. There<strong>for</strong>e<br />

Local <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s (LBAPs) have been developed, and more recently<br />

organisations are producing <strong>the</strong>ir own BAPs.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, or <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ NCN BAP, is<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ commitment to biodiversity along its ever-growing network of cycling and walking<br />

routes. The <strong>Network</strong> comprises linear features that act as wildlife corridors linking habitats<br />

and species which would o<strong>the</strong>rwise be isolated from each o<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong> would like to acknowledge <strong>the</strong> work of drafting this document by Michael Woods<br />

Associates. It is a working document that has been reviewed by Dr Ant Maddock of <strong>the</strong><br />

Joint Nature Conservation Committee on behalf of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Reporting and<br />

In<strong>for</strong>mation Group (BRIG) which advises <strong>the</strong> UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Partnership and will be<br />

reviewed and updated every five years.<br />

The <strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP highlights <strong>the</strong> organisation’s commitment to promoting sustainable<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms of transportation while also protecting and enhancing wildlife and <strong>the</strong> natural<br />

environment.<br />

The <strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP includes Habitat <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s <strong>for</strong> hedgerows, lowland calcareous<br />

grasslands and banks and verges and Species <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s <strong>for</strong> bats, badger, dormouse,<br />

slow worm and great crested newt. There are also generic action plans <strong>for</strong> birds and<br />

invertebrates.<br />

The <strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP includes in<strong>for</strong>mation on <strong>the</strong> recommended survey techniques and<br />

<strong>the</strong> recommended methods <strong>for</strong> treating invasive species.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

6

1. Introduction to biodiversity in <strong>the</strong> UK<br />

1.1 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> is a term used to describe <strong>the</strong> variety and richness of all living things. The<br />

term encompasses all life <strong>for</strong>ms, and includes both <strong>the</strong> genetic variation within<br />

species, <strong>the</strong> interactions between species and <strong>the</strong> relationships between species and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir habitats. <strong>Biodiversity</strong> is <strong>the</strong> shortened <strong>for</strong>m of two words "biological" and<br />

"diversity." The Convention on Biological Diversity defines biological diversity as “<strong>the</strong><br />

variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial,<br />

marine and o<strong>the</strong>r aquatic ecosystems and <strong>the</strong> ecological complexes of which <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”.<br />

1.2 The United Kingdom was one of over 100 countries that pledged to develop a<br />

national strategy <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> conservation and sustainable use of Biological Diversity at<br />

<strong>the</strong> UN Conference on Environment and Development at <strong>the</strong> Earth Summit in Rio de<br />

Janeiro in 1992. The UK Government was also one of <strong>the</strong> first signatories to <strong>the</strong><br />

Convention to produce a biodiversity strategy and action plan in January 1994 –<br />

‘<strong>Biodiversity</strong>: The UK <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>’ (HMSO 1994).<br />

1.3 The Government has taken a lead in setting <strong>the</strong> approach <strong>for</strong> biodiversity<br />

conservation, but in order to succeed, action needs to be taken at all levels and in all<br />

sectors of <strong>the</strong> community. The UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong> BAP process is being steered by <strong>the</strong><br />

UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Partnership Standing Committee, which replaced <strong>the</strong> UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong><br />

Group (UKBG) in 2002. The Chairs of <strong>the</strong> four country <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Groups,<br />

representatives of <strong>the</strong> four country nature conservation agencies and representatives<br />

of <strong>the</strong> NGO community are standing members. Two support groups have been set up<br />

to help <strong>the</strong> Standing Committee. These are <strong>the</strong> UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Reporting and<br />

In<strong>for</strong>mation Group (BRIG) and <strong>the</strong> UK <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Research Advisory Group (BRAG).<br />

1.4 There are over 150 Local BAPs in use throughout <strong>the</strong> UK, each with targeted actions.<br />

Each LBAP is based on partnerships that identify local priorities and determine <strong>the</strong><br />

contribution <strong>the</strong>y can make to <strong>the</strong> delivery of <strong>the</strong> national species and habitat action<br />

plan targets. Often, but not always, LBAPs con<strong>for</strong>m to county boundaries. A healthy<br />

natural environment benefits everyone, and biodiversity conservation has an<br />

important part to play in this.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

7

2. Introduction to <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

2.1 About <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

2.1.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong> is <strong>the</strong> UK's leading sustainable transport charity. Our vision is a world in<br />

which people choose to travel in ways that benefit <strong>the</strong>ir health and <strong>the</strong> environment.<br />

We are <strong>the</strong> charity behind <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, Safe Routes to Schools, Bike<br />

It, Liveable Neighbourhoods, TravelSmart and many o<strong>the</strong>r projects that are working<br />

everyday on practical and innovative solutions to transport challenges.<br />

2.1.2 <strong>Sustrans</strong> was started in 1977 by a group of Bristol environmentalists, who set up a<br />

cycling group called <strong>Cycle</strong>bag. Within two years <strong>the</strong> group began a programme of<br />

building cycle routes, which has continued unabated <strong>for</strong> nearly 30 years.<br />

2.1.3 After 15 years’ experience of building paths, <strong>Sustrans</strong> began to capture <strong>the</strong> public<br />

imagination and launched a Supporter Programme. Supporter numbers rose from<br />

200 in 1993 to 40,000 in 2005. By 1995 <strong>Sustrans</strong> was in a position to make a realistic<br />

bid to <strong>the</strong> Millennium Commission <strong>for</strong> Lottery funds to help construct <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong><br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong>. The original bid was <strong>for</strong> a 6,500-mile network by 2005 with 2,500<br />

miles of routes built by <strong>the</strong> year 2000. The enthusiasm <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> project shown by local<br />

authorities all over <strong>the</strong> country has since increased this total to 12,000 miles.<br />

2.1.4 The bid was successful and <strong>Sustrans</strong> was awarded £43.5 million. Although this is a<br />

huge amount, it only represented 20% of <strong>the</strong> total costs of <strong>the</strong> first phase of <strong>the</strong><br />

project. The remainder came from a variety of sources including local authorities,<br />

development agencies, <strong>the</strong> European Union, <strong>the</strong> Highways Agency, <strong>the</strong> cycle trade<br />

and industry, and from generous contributions from <strong>Sustrans</strong> Supporters.<br />

2.2 <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ projects<br />

2.2.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong> works on a range of practical and innovative projects that allow people to<br />

choose to travel in healthy and environmentally friendly ways, as well as contributing<br />

towards wider regional and national government policies and objectives. These<br />

projects are summarised on page 9.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

8

Project<br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Safe Routes to Schools<br />

Liveable<br />

Neighbourhoods<br />

TravelSmart<br />

Bike It<br />

Art and <strong>the</strong> Travelling<br />

Landscape<br />

Volunteer Rangers<br />

Active Travel<br />

Research and<br />

Monitoring<br />

General Description<br />

A comprehensive network of safe and attractive places to cycle<br />

and walk throughout <strong>the</strong> UK. <strong>Sustrans</strong> delivers <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> with<br />

many partners and 12,000 miles of route are now open. <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

has a range of services to help people to get <strong>the</strong> most from <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Network</strong>. We provide a free public in<strong>for</strong>mation service, produce<br />

high quality maps and guides, commission public artworks on<br />

<strong>the</strong> routes and run a national volunteer programme, with nearly<br />

2000 volunteer rangers looking after and helping to promote <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

local routes. In 2002, we were awarded <strong>the</strong> Queen’s Award <strong>for</strong><br />

Enterprise in recognition of our work on <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong><br />

<strong>Network</strong>. In 2005 <strong>the</strong> project won <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> Lottery ‘Helping<br />

Hands Award’, decided by public vote <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> lottery project with<br />

greatest national impact.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong> pioneered this initiative in <strong>the</strong> UK, working with schools<br />

to make cycling and walking to school both safe and fun.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong> has also built hundreds of Links to Schools from <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, giving children traffic-free routes and<br />

parents peace of mind.<br />

Updating city living <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> 21 st century by putting people at <strong>the</strong><br />

heart of <strong>the</strong>ir community. Places where children can play safely,<br />

people can shop locally, with plenty of open and public spaces<br />

accessible to all.<br />

Pioneered by <strong>Sustrans</strong> in <strong>the</strong> UK, offering a unique service that<br />

gives households <strong>the</strong> tailor-made in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>the</strong>y need to walk,<br />

cycle and use public transport more.<br />

We know that millions of children want to cycle to school in this<br />

country - yet only 1% do. <strong>Sustrans</strong> has stepped in to sort this out<br />

with Bike It, a ground-breaking project which has already<br />

quadrupled <strong>the</strong> number of children cycling to its target schools.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong> believes getting children to start cycling now is <strong>the</strong> key<br />

to <strong>the</strong> future of sustainable transport.<br />

Creating more memorable journeys on <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong><br />

<strong>Network</strong> by commissioning quality public artworks, from<br />

sculptures through seats and drinking fountains, creating public<br />

spaces that can be appreciated by all.<br />

Nearly 2000 volunteers across <strong>the</strong> UK working with <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

communities on major <strong>Sustrans</strong> projects.<br />

Persuading government to promote walking and cycling as a way<br />

of combating obesity, heart disease and cancer.<br />

<strong>National</strong> monitoring programme which collects data from around<br />

<strong>the</strong> UK and uses this to produce an annual report on cycle usage<br />

around <strong>the</strong> UK. This has been a powerful tool in showing that<br />

cycling has been growing over recent years, particularly on carfree<br />

routes. The data is produced mostly from automatic<br />

counters managed by local authorities and is supplemented with<br />

manual counts.<br />

2.3 Flagship project<br />

2.3.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong> is working to establish and promote a <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> in <strong>the</strong> United<br />

Kingdom. The <strong>Network</strong> so far consists of some 12,000 miles of cycle routes passing<br />

through <strong>the</strong> centres of most major towns and cities in <strong>the</strong> UK and within one mile of<br />

over 50% of <strong>the</strong> UK’s population. It serves <strong>the</strong> urban areas, provides access to <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

9

countryside <strong>for</strong> local journeys, and creates a regional network connecting settlements<br />

along its way. Approximately one-third is traffic free and <strong>the</strong> rest on traffic-calmed<br />

minor town and country roads. Traffic-free sections provide a suitable place <strong>for</strong><br />

children and new cyclists to practice <strong>the</strong>ir skills. Many routes are also used by<br />

walkers, wheelchair users and, in some cases, horse riders. The project reaches all<br />

parts of <strong>the</strong> UK, benefits all sectors of society and has both a local and national<br />

significance.<br />

2.3.2 The concept of cycling and walking as a method of sustainable transport was<br />

accorded national recognition in 1995 when <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> became <strong>the</strong><br />

first major, and truly national, project to gain <strong>the</strong> support of <strong>the</strong> Millennium<br />

Commission. Working in conjunction with Local Authorities and o<strong>the</strong>rs to implement<br />

<strong>the</strong> practical work, <strong>Sustrans</strong> oversees <strong>the</strong> co-ordination, design and standards of <strong>the</strong><br />

overall project.<br />

2.3.3 The majority of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> uses pre-existing paths or linear features of one sort or<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r, with very few completely new routes being created. A very small proportion,<br />

less than 15% of <strong>the</strong> entire <strong>Network</strong>, will require new construction. Many paths use<br />

disused railway lines and include restoration of some of <strong>the</strong>ir unimproved grassland<br />

embankments and cuttings. Over a typical length of disused railway, a 2.5 metre wide<br />

path will utilise under 10% of <strong>the</strong> area. This minimises <strong>the</strong> environmental impact of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, particularly from <strong>the</strong> construction process, and <strong>the</strong> disturbance to local<br />

wildlife that is often already accustomed to human activity.<br />

2.3.4 The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, and in particular <strong>the</strong> traffic-free sections, comprises<br />

linear features that act as wildlife corridors linking habitats and species which would<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise be isolated from each o<strong>the</strong>r. Fur<strong>the</strong>r investigation into <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> cycle<br />

and walking routes by wildlife would be valuable and <strong>Sustrans</strong> is involved in a number<br />

of research projects including <strong>the</strong> use of bridges along cycle routes by <strong>for</strong>aging bats.<br />

The <strong>Network</strong> also <strong>for</strong>ms a valuable resource <strong>for</strong> nature education, and <strong>Sustrans</strong> aims<br />

to increase cyclists’ and walkers’ enjoyment of nature along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> by<br />

enhancing habitat <strong>for</strong> wildlife, and through interpretation where possible. For sensitive<br />

sites, management plans are being produced to protect and enhance <strong>the</strong> route <strong>for</strong><br />

wildlife as well as <strong>for</strong> users. These include short-term maintenance e.g. cutting<br />

regimes and timing, and longer-term management e.g. embankments and cuttings,<br />

bramble, hedgerows, etc. which incorporate maximising wildlife interest. The<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP is just one of a number of initiatives that <strong>Sustrans</strong> is developing to<br />

maximise <strong>the</strong> wildlife potential along its routes. <strong>Sustrans</strong> produces a series of<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation sheets, one of which, ‘Ways <strong>for</strong> Wildlife – wildlife, cycle paths and traffic’,<br />

is specifically targeted at <strong>the</strong> value of traffic-free cycle routes to wildlife. A copy of<br />

this leaflet can be found in Appendix 1.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

10

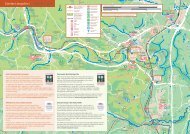

2.3.5 Map of <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

11

3. <strong>Biodiversity</strong> commitment<br />

3.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong> aims to encourage people to choose to travel in ways that benefit <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

health and <strong>the</strong> environment. The <strong>Network</strong> is a positive demonstration of <strong>the</strong> UK’s<br />

commitment to sustainability.<br />

3.2 A widely used and accepted international definition of sustainable development is:<br />

“development which meets <strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>the</strong> present without compromising <strong>the</strong> ability<br />

of future generations to meet <strong>the</strong>ir own needs” 1 . <strong>Sustrans</strong> considers that a policy of<br />

continuous reduction in vehicular travel is central to this goal and should be an<br />

objective of all environmental groups and organisations. This, in turn, helps <strong>the</strong><br />

Government fulfil its commitments under <strong>the</strong> Rio Convention and really does enable<br />

people to ‘Think globally, act locally’.<br />

3.3 Reflecting this commitment to act locally, <strong>Sustrans</strong> seeks to minimise <strong>the</strong> impacts on<br />

wildlife and its habitats during expansion of <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong>. <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

recognises <strong>the</strong> importance of its traffic-free paths as wildlife habitats and corridors to<br />

help reduce isolation and fragmentation. They also offer potential <strong>for</strong> educating <strong>the</strong><br />

public about local wildlife and geology. In constructing and managing paths and<br />

routes <strong>for</strong> which it is responsible, <strong>Sustrans</strong> will aspire to do this with high biodiversity<br />

and geological gain as an objective, using <strong>the</strong> framework provided by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Biodiversity</strong><br />

<strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>.<br />

3.4 In June 2007 a new list of UK priorities was identified, covering 65 habitats and 1149<br />

species. By early 2008 all of <strong>the</strong>se priority habitats and species will have national<br />

action plans. The LBAPs identify local priorities and determine <strong>the</strong> contribution <strong>the</strong>y<br />

will make to <strong>the</strong> delivery of <strong>the</strong> national targets contained in <strong>the</strong> UK BAP. As <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong> <strong>Network</strong> covers <strong>the</strong> whole of <strong>the</strong> UK, it will need to consider a total of 162<br />

Local <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s. There<strong>for</strong>e partnerships will play a vital part in <strong>the</strong><br />

successful implementation of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong> BAP.<br />

3.5 The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> can be found throughout <strong>the</strong> UK. As <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

consists of a series of linear features, <strong>the</strong> actions set out in <strong>the</strong> habitat and species<br />

action plans reflect this.<br />

4. Key activities and <strong>the</strong>ir impact on biodiversity<br />

Activity<br />

Encourage shift from private car use to<br />

cycling<br />

15% of routes of <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> will<br />

require new-build tracks while o<strong>the</strong>r linear<br />

features with no current public use (but often<br />

with wildlife value) will require conversion<br />

Impact<br />

Reduce negative environmental impacts of<br />

road traffic (air pollution, health and safety,<br />

threats to wildlife)<br />

Disturbance to local wildlife and limited<br />

direct loss of habitat (addressed below)<br />

1 World Commission on Environment and Development’s (<strong>the</strong> Brundtland Commission) report Our Common Future (Ox<strong>for</strong>d: Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

University Press, 1987)<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

12

On-going key action plan items and how <strong>the</strong>se make a positive contribution<br />

Proposed <strong>Action</strong><br />

Continue liaison with conservation<br />

organisations (Natural England, Countryside<br />

Council <strong>for</strong> Wales, Scottish Natural Heritage &<br />

Environment Heritage Service Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland)<br />

and expertise, i.e. retain ecological consultant<br />

to provide advice<br />

<strong>Action</strong> to minimise impact of building new<br />

cycle routes:<br />

Contribution to biodiversity<br />

Increase awareness and knowledge of<br />

biodiversity and raise environmental<br />

standards<br />

<br />

Ecological surveys of areas of proposed<br />

paths (e.g. those running through/close to<br />

SSSIs etc.)<br />

Reduce threats and impacts to habitats and<br />

species<br />

<br />

Sensitive siting of new routes<br />

Contracts to include environmental<br />

responsibilities (general as well as<br />

mitigation of construction impacts)<br />

Improve environmental per<strong>for</strong>mance of<br />

contractors<br />

<br />

Assess <strong>the</strong> use of recycled or local<br />

materials as far as appropriate in<br />

construction<br />

Reduce impacts on biodiversity from<br />

extraction & supply of natural resources<br />

Use of tarmac as a path surface Provides a long lasting smooth surface and<br />

reduces detrimental impacts of repeated<br />

repairs which can affect adjacent habitats<br />

and increase extraction<br />

<br />

Appropriate screening of cycle routes at<br />

sensitive points taking into account <strong>the</strong><br />

need <strong>for</strong> attractive and interesting views<br />

Work to enhance/protect biodiversity along<br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> routes:<br />

<br />

Produce management plans <strong>for</strong> specific<br />

routes (those passing through sensitive<br />

areas (e.g. SSSIs) or those used by priority<br />

species)<br />

Conserve and enhance biodiversity<br />

Sensitive maintenance of routes e.g.<br />

wildlife friendly mowing regimes,<br />

enhancement of on-site ditches <strong>for</strong> wildlife,<br />

maintaining arboreal routes and enhancing<br />

hedgerows, etc.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Support Rangers’ maintenance work on<br />

routes (e.g. training by retained ecological<br />

expert, articles on enhancing routes <strong>for</strong><br />

wildlife in <strong>the</strong> Ranger newsletter, etc.); work<br />

with local wildlife trusts and o<strong>the</strong>r groups<br />

Control invasive alien species such as<br />

Japanese knotweed, Giant hogweed and<br />

Himalayan balsam<br />

Provide, where possible, wildlife and/or<br />

geological interpretation of interesting<br />

features<br />

Promote biodiversity awareness and<br />

knowledge to improve management of routes<br />

Promote biodiversity awareness and<br />

appreciation of nature by users of paths<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

13

5. <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ partnerships<br />

5.1.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong> currently has active relationships with over 2,000 partners in <strong>the</strong> UK alone.<br />

In nearly all its work, <strong>Sustrans</strong> tries to maximise <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of its activities by<br />

not only creating new routes and projects itself, but by getting o<strong>the</strong>r bodies to jointly<br />

or independently fund similar schemes. <strong>Sustrans</strong> sees <strong>the</strong> successful implementation<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP as an ideal opportunity to expand opportunities <strong>for</strong><br />

partnership working.<br />

5.1.2 <strong>Sustrans</strong> has direct management control over <strong>the</strong> (approx.) 400 miles of traffic-free<br />

paths that it owns. <strong>Sustrans</strong> is also responsible <strong>for</strong> maintaining additional traffic-free<br />

sections owned by o<strong>the</strong>r authorities. In <strong>the</strong> first instance, The <strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP will<br />

be implemented on sections of <strong>Network</strong> which <strong>Sustrans</strong> owns. However, it is<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ aspiration that biodiversity will be maximised on all sections of traffic-free<br />

route.<br />

5.2 The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> as an example of partnership<br />

5.2.1 The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> is a partnership par excellence - hundreds of different<br />

bodies are involved. Most important among <strong>the</strong>se are local authorities in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

commitments to local route sections, <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>for</strong> Transport, <strong>the</strong> Scottish<br />

Government, <strong>the</strong> Welsh Assembly Government, <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>for</strong> Regional<br />

Development <strong>for</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland and <strong>the</strong> Highways Agency.<br />

5.2.2 Disused railway routes and links to working stations have been developed in<br />

partnership with <strong>Network</strong> Rail, BRB Residency Ltd, Regional Development Agencies,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Welsh Development Agency, <strong>the</strong> Railway Heritage Trust and several rail operating<br />

companies.<br />

5.2.3 Forest route sections rely on <strong>the</strong> support of Forest Enterprise and <strong>the</strong> Forest Service<br />

in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland. Countryside sections involve Natural England, Countryside<br />

Council <strong>for</strong> Wales, Scottish Natural Heritage, Woodland Trust and Central Scotland<br />

Countryside Trust, amongst o<strong>the</strong>rs. <strong>National</strong> Parks (a Memorandum of Understanding<br />

between <strong>Sustrans</strong> and <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> Parks Transport Officers Group was signed in <strong>the</strong><br />

summer of 2005), tourist bodies and wildlife and heritage organisations are also<br />

critical <strong>for</strong> progress. <strong>Sustrans</strong> has worked closely with <strong>the</strong> Lee Valley Park,<br />

Snowdonia and Brecon Beacons <strong>National</strong> Parks, Northumberland <strong>National</strong> Park, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust. Besides supporting local <strong>Network</strong> sections, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>National</strong> Trust, Cadw and English Heritage are also encouraging sustainable travel to<br />

heritage sites.<br />

5.2.4 British Waterways has developed positive policies on towpath cycling <strong>for</strong> links that<br />

are critical <strong>for</strong> <strong>Network</strong> continuity. The Environment Agency and several local canal<br />

trusts are also involved. <strong>Sustrans</strong> has a close partnership with <strong>the</strong> Groundwork Trust<br />

who has built several sections of <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

5.2.5 The CTC (Cyclists Touring Club) and <strong>the</strong> British Cycling Federation have become<br />

closer working partners, and <strong>the</strong> London Cycling Campaign and dozens of o<strong>the</strong>r local<br />

cycling campaigns are involved. <strong>Sustrans</strong> is working more closely with <strong>the</strong> Ramblers’<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

14

Association, <strong>the</strong> British Horse Society, <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> Federation of Anglers, <strong>the</strong><br />

Pedestrians Association and <strong>the</strong> Joint Mobility Unit.<br />

5.2.6 <strong>Sustrans</strong> will expand this partnership by linking into LBAPs where possible to ensure<br />

that as well as meeting its own targets, local targets are incorporated and <strong>the</strong> LBAP<br />

co-ordinator is aware that this is happening.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

15

6. Objective of <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong><br />

<strong>Network</strong><br />

6.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong> is an organisation committed to <strong>the</strong> promotion of sustainable transport, but<br />

also realises that <strong>the</strong>re is a delicate balance between <strong>the</strong> creation of safe routes and<br />

<strong>the</strong> conservation of biodiversity. <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ NCN BAP has one objective:<br />

“To provide a series of safe and enjoyable routes that promote sustainable <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

transportation, while ensuring that <strong>the</strong> biodiversity along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> is enhanced and<br />

protected, within <strong>the</strong> constraints of safety and resources”.<br />

6.2 <strong>Sustrans</strong> will meet this objective by:<br />

Developing partnerships<br />

Educating staff<br />

Providing in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>for</strong> users<br />

Ensuring biodiversity aims are included in management plans <strong>for</strong> land managed<br />

by <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

Seeking additional funding to meet <strong>the</strong>se additional objectives.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

16

7. Links with Local <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s<br />

7.1 <strong>Sustrans</strong> will, where possible, develop partnerships to implement local BAP targets,<br />

as well as those set out in this document.<br />

7.2 It is not practical <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ NCN BAP to cover every possible species and habitat<br />

found along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong>. To ensure that <strong>the</strong> targets are achievable and, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e,<br />

that <strong>the</strong> BAP can be implemented it has been decided to produce generic action<br />

plans <strong>for</strong> birds and invertebrates, ra<strong>the</strong>r than list actions <strong>for</strong> individual species. The<br />

BAP also concentrates on those species and habitats most commonly found along its<br />

length, some of which are not a UK priority.<br />

7.3 This does not mean that o<strong>the</strong>r species and habitats found along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> will be<br />

ignored, it simply means that <strong>the</strong> species and habitats listed will be promoted and<br />

monitored through <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ on-going programme of works.<br />

7.4 New species and habitat action plans can be added at <strong>the</strong> five-year review and will<br />

be influenced by changes to <strong>the</strong> UK BAP as well as new records and in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

about biodiversity along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

7.5 When operating on a project, <strong>Sustrans</strong> will contact <strong>the</strong> Local <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

co-ordinator <strong>for</strong> advice and ideas on how <strong>the</strong> planned works can assist in <strong>the</strong><br />

implementation of that particular LBAP. Nature conservation issues will be<br />

incorporated from <strong>the</strong> earliest stages of project development as part of <strong>the</strong> decisionmaking<br />

process.<br />

7.6 <strong>Sustrans</strong> does not manage all <strong>the</strong> paths that it develops, so <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP<br />

will be used to advise <strong>the</strong> decision-making process and influence <strong>the</strong> future<br />

management of paths that make up <strong>the</strong> NCN.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

17

8. Monitoring, reviewing and reporting<br />

8.1 The <strong>Sustrans</strong> NCN BAP is a working document. It will be reviewed every five years. At<br />

this review stage new Habitat and Species <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s can be considered <strong>for</strong><br />

inclusion. This will be subject to changes at a UK level, as well as in<strong>for</strong>mation from<br />

internal sources (e.g. management plans, ecological surveys).<br />

8.2 <strong>Action</strong>s will also be monitored <strong>for</strong> progress. If actions have been completed, <strong>the</strong>se<br />

can <strong>the</strong>n be removed or updated. HAPs and SAPs can also be removed at this stage,<br />

should this be necessary.<br />

8.3 The first review is scheduled to take place in 2012.<br />

8.4 Once <strong>the</strong> actions have been reviewed, <strong>the</strong>ir progress will be reported on <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> Reporting System (BARS) and survey data sent to <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong><br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (NBN).<br />

8.5 BARS is an in<strong>for</strong>mation system that supports <strong>the</strong> planning, monitoring and reporting<br />

requirements of national, local and company <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s (BAPs). It also<br />

allows users to learn about <strong>the</strong> progress being made with local and national BAPs.<br />

Using this system allows <strong>the</strong> progress of <strong>Sustrans</strong>’ NCN BAP to be monitored quickly<br />

and efficiently, without <strong>the</strong> need of developing a new system (http://www.ukbapreporting.org.uk/default.asp).<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

18

9. Habitat <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s<br />

9.1 Hedgerows<br />

9.1.1 Description<br />

A hedgerow is defined as any boundary line of trees or shrubs over 20m long and less<br />

than 5m wide at <strong>the</strong> base, provided that at one time <strong>the</strong> trees or shrubs were more or<br />

less continuous. It includes an earth bank or wall only where such a feature occurs in<br />

association with a line of trees or shrubs. This includes ‘classic’ shrubby hedgerows,<br />

lines of trees, shrubby hedgerows with trees and very gappy hedgerows (where each<br />

shrubby section may be less than 20m long, but <strong>the</strong> gaps are less than 20m).<br />

Priority hedgerows should be those comprising 80% or more cover of any native<br />

tree/shrub species. This does not include archaeophytes and sycamore. For <strong>the</strong><br />

purposes of <strong>the</strong> UK BAP ‘native’ will not be defined fur<strong>the</strong>r; it will be left up to <strong>the</strong><br />

Countries to provide guidance on this as <strong>the</strong>y consider appropriate.<br />

Hedges are not just important <strong>for</strong> biodiversity, but are also recognisable landscape<br />

features, act as boundaries in farming and are important <strong>for</strong> cultural, historical and<br />

archaeological reasons.<br />

They are a primary habitat <strong>for</strong> at least 47 extant species of conservation concern in<br />

<strong>the</strong> UK, including 13 globally threatened or rapidly declining ones. They are especially<br />

important <strong>for</strong> butterflies and moths, farmland birds, bats and dormice. Over 600 plant<br />

species, 1500 insects, 65 birds and 20 mammals have been recorded at some time<br />

living or feeding in hedgerows.<br />

Hedgerows also act as wildlife corridors <strong>for</strong> many species, including bats, reptiles<br />

and amphibians, allowing dispersal and movement between o<strong>the</strong>r habitats.<br />

9.1.2 Optimum survey time<br />

According to Defra’s ‘Hedgerow Survey Handbook’ (published March 2007), “<strong>the</strong> field<br />

survey period extends approximately from April to October, depending on <strong>the</strong> part of<br />

<strong>the</strong> country. June and July are ideal months, particularly where surveys include<br />

assessments of <strong>the</strong> ground flora. Local hedgerow management practices are also<br />

important.”<br />

9.1.3 Current status<br />

Hedgerows are a UK BAP Priority Habitat. The current total length of hedgerow in <strong>the</strong><br />

UK is estimated at 280,000 miles. Hedgerows continue to decline through lack of<br />

survey work or unsympa<strong>the</strong>tic management of <strong>the</strong> adjacent land and of <strong>the</strong><br />

hedgerows <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

9.1.4 Legislation<br />

Certain hedgerows are protected under <strong>the</strong> Hedgerow Regulations 1997, which were<br />

made under <strong>the</strong> Environment Act 1995 in England and Wales. These Regulations<br />

prevent <strong>the</strong> removal of most countryside hedgerows without first submitting a<br />

hedgerow removal notice to <strong>the</strong> Local <strong>Plan</strong>ning Authority. In Scotland and Nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Ireland <strong>the</strong>re is no specific legislation <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> protection of hedgerows, as <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

19

fewer found in Scotland and Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland compared to <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> United<br />

Kingdom.<br />

9.1.5 Current factors affecting <strong>the</strong> habitat<br />

Removal of hedges <strong>for</strong> development or agricultural purposes.<br />

Inappropriate cutting, ei<strong>the</strong>r at <strong>the</strong> wrong time of year or too frequently.<br />

Changes in hedgerow management. Hedges are no longer cut or laid, and many<br />

are simply replaced by fencing.<br />

Too frequent and badly timed cutting leading to poor habitat conditions, <strong>the</strong><br />

development of gaps and probable species changes.<br />

Use of herbicides, pesticides and fertilisers right up to <strong>the</strong> bases of hedgerows<br />

leading to nutrient enrichment and a decline in species diversity.<br />

Increased stocking rates, which leads to hedgerow damage.<br />

9.1.6 <strong>Action</strong>s<br />

Ensure that all work adjacent to hedgerows encourages <strong>the</strong> retention and<br />

favourable management of ancient and/or species-rich hedgerows.<br />

Encourage favourable management of ancient and/or species-rich path side<br />

hedges, especially with regard to cutting practices.<br />

Consider <strong>the</strong> development of hedge management skills through training,<br />

especially <strong>for</strong> contractors and volunteer Rangers.<br />

Ensure management plans promote <strong>the</strong> protection and management of hedges<br />

and seek to minimise adverse effects on hedges from developing <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

Continue to promote awareness among staff of <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> appropriate<br />

management to maintain biodiversity.<br />

9.2 Lowland Calcareous Grasslands<br />

9.2.1 Description<br />

These develop on shallow lime-rich soils, generally found overlying limestone rocks,<br />

including chalk. They are mainly found on distinct topographic features such as<br />

escarpments or dry valley slopes and sometimes on ancient earthworks in<br />

landscapes influenced by <strong>the</strong> underlying limestone geology. They may also develop in<br />

situations where alkaline rock has been exposed, <strong>for</strong> example in quarries and road<br />

cuttings, and even on industrial spoil such as flue-ash or railway ballast.<br />

9.2.2 Optimum survey time<br />

June and July.<br />

9.2.3 Current status<br />

Calcareous Grassland is a UK BAP Priority Habitat. It is estimated that lowland<br />

calcareous grasslands have declined by approximately 50% in <strong>the</strong> last 50 years.<br />

9.2.4 Current factors affecting <strong>the</strong> habitat<br />

Agricultural intensification by use of fertilisers, herbicides and o<strong>the</strong>r pesticides, reseeding<br />

or ploughing <strong>for</strong> arable crops.<br />

Farm specialisation towards arable cropping has reduced <strong>the</strong> availability of<br />

livestock in many lowland areas. The result is <strong>the</strong> increasing dominance of coarse<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

20

grasses such as tor grass Brachypodium pinnatum and false oat grass<br />

Arrhena<strong>the</strong>rum elatius and invasion by scrub and woodland, leading to losses of<br />

calcareous grassland flora and fauna.<br />

Development activities such as mineral and rock extraction, road building, housing<br />

and landfill.<br />

Localised af<strong>for</strong>estation with hardwoods and softwoods.<br />

Recreational pressure bringing about floristic changes associated with soil<br />

compaction at some key sites.<br />

Invasion by non-native plants, including bird-sown Cotoneaster species, causes<br />

problems by smo<strong>the</strong>ring calcareous grassland communities at some sites.<br />

Atmospheric pollution and climate change, <strong>the</strong> influence of which is not fully<br />

assessed.<br />

9.2.5 <strong>Action</strong>s<br />

Encourage appropriate public access <strong>for</strong> observation and enjoyment of lowland<br />

calcareous grassland.<br />

Reduce invasion by scrub and trees.<br />

Use appropriate cutting methods and regimes to benefit <strong>the</strong> grassland.<br />

9.3 Banks and verges<br />

9.3.1 Description<br />

There are many thousands of miles of banks and verges throughout <strong>the</strong> UK<br />

associated with roads and railways (both used and disused). These verges can take<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m of hedges and banks, all of which represent small linear areas of seminatural<br />

habitat, and collectively are an important natural resource. Banks and verges<br />

can often support species rich grasslands, mixed scrub, woodlands, and, along<br />

disused railways, calcareous grasslands. They can provide an important habitat and<br />

food source <strong>for</strong> a wide variety of species, from badgers and bats to butterflies and<br />

orchids. Banks and verges are also very important wildlife corridors, allowing a huge<br />

variety of species to commute along <strong>the</strong>m, and <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e link up o<strong>the</strong>r habitats.<br />

Habitats likely to be encountered on banks and verges along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

are described below.<br />

<br />

<br />

Grasslands<br />

The biodiversity of <strong>the</strong> grassland found along a verge will depend on <strong>the</strong><br />

maintenance regime that is employed. Cutting too early in a season can prevent<br />

many species flowering and setting seed, so removing an important food resource<br />

<strong>for</strong> birds and insects. Late cutting is often <strong>the</strong> preferred method as this<br />

encourages annual and late perennials to grow, so increasing <strong>the</strong> biodiversity. In<br />

many cases it is important to remove <strong>the</strong> cuttings as o<strong>the</strong>rwise <strong>the</strong>se will increase<br />

<strong>the</strong> nutrients in <strong>the</strong> area, so changing <strong>the</strong> flora of <strong>the</strong> area. As a general guide,<br />

most grasslands should be cut once in September, with <strong>the</strong> cuttings<br />

removed/raked into habitat piles.<br />

Woodlands<br />

Woodland edges provide excellent habitats <strong>for</strong> a range of species including bats,<br />

dormice and a wide variety of birds and butterflies.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

21

Hedgerows (see above action plan)<br />

A hedgerow that contains a good variety of trees and shrubs can provide food and<br />

shelter <strong>for</strong> a huge variety of animals including birds, mammals and insects.<br />

Hedges are also important as wildlife corridors, allowing species to commute<br />

between habitats. They need to be maintained in a sympa<strong>the</strong>tic way that will<br />

improve <strong>the</strong> biodiversity found within <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Scrub<br />

It is an important component of <strong>the</strong> landscape and a natural part of o<strong>the</strong>r habitats<br />

such as grassland and woodland. It provides shelter and food a variety of species<br />

including birds, mammals and invertebrates. Scrub of varying age, species and<br />

structure supports <strong>the</strong> widest variety of wildlife. Some species require particular<br />

shrubs and o<strong>the</strong>rs a range of habitats in a small patch of scrub. It is important to<br />

maintain all growth stages, from bare ground through young and old growth to<br />

decaying wood.<br />

Scrub needs regular maintenance to ensure that it does not dominate an area,<br />

and so reduce <strong>the</strong> overall biodiversity. Bramble is very important but can be a<br />

particular problem. With regular cutting it can be kept in check (see section<br />

13.1.1).<br />

9.3.2 Optimum survey time<br />

April, May, June and July, depending on <strong>the</strong> habitat.<br />

9.3.3 Current status<br />

Banks are not currently a UK BAP priority habitat in <strong>the</strong>ir own right (though field<br />

banks maybe included as such in <strong>the</strong> next review and roadside verges will be<br />

recognised within relevant grassland priority habitat types). However, many of <strong>the</strong><br />

habitats found along banks and verges are priority habitats. Banks and verges are<br />

probably one of <strong>the</strong> most widespread habitats throughout <strong>the</strong> UK. If managed<br />

properly <strong>the</strong>y can be a valuable resource with a huge potential <strong>for</strong> enhancement.<br />

9.3.4 Status in relation to <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

Banks and verges will be found in varying <strong>for</strong>ms throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong><br />

<strong>Network</strong>, ranging from hedgerows to grasslands and woodland to scrub.<br />

9.3.5 Legislation<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> banks and verges <strong>the</strong>mselves have no protection, some of <strong>the</strong> habitats<br />

found along <strong>the</strong>m may be protected. They are a very valuable resource along <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong> <strong>Network</strong> and one that <strong>Sustrans</strong> can enhance through its regular<br />

maintenance regime.<br />

9.3.6 Current factors affecting <strong>the</strong> habitat<br />

Neglect through mismanagement both through over cutting and undercutting.<br />

Lack of appreciation of <strong>the</strong> importance as a habitat.<br />

Invasion by non-native species e.g. Japanese knotweed (see section 13.3).<br />

9.3.7 <strong>Action</strong>s<br />

Education about <strong>the</strong> importance of banks and verges as a habitat.<br />

Encourage appropriate public access <strong>for</strong> observation and enjoyment of banks and<br />

verges.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

22

Contribute to <strong>the</strong> implementation of relevant priority species and habitat action<br />

plans, through <strong>the</strong> integration of management requirements and advice, in<br />

conjunction with relevant LBAP partnerships.<br />

Control any patches of alien plant species along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> including Japanese<br />

knotweed, Himalayan balsam and giant hogweed (see section 13).<br />

Banks and verges that are of poor quality will be improved.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

23

10. Species <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s<br />

10.1 Birds<br />

10.1.1 Description<br />

Birds are one of <strong>the</strong> most common wildlife species that people have regular contact<br />

with. Many of <strong>the</strong> once familiar British birds are now in serious decline.<br />

10.1.2 Optimum survey time<br />

The birds <strong>the</strong>mselves can be surveyed <strong>for</strong> at any time. However, <strong>the</strong> most important<br />

time of <strong>the</strong> year to carry out a thorough bird survey would be during <strong>the</strong> nesting<br />

season which begins in early March and continues through to late August. As it is <strong>the</strong><br />

nests that are protected, it is essential to identify any possible nesting sites, as this<br />

may affect <strong>the</strong> timing of works along routes.<br />

10.1.3 Current status<br />

Many of Britain’s bird species are in decline, including ‘common’ species such as <strong>the</strong><br />

house sparrow and starling, which are both now UK BAP priority species.<br />

10.1.4 Status in relation to <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

Birds can be encountered along <strong>the</strong> entire length of <strong>Sustrans</strong> routes. Species found<br />

will be dependent on <strong>the</strong> adjacent habitat and <strong>the</strong> time of year.<br />

10.1.5 Legislation<br />

All British birds, <strong>the</strong>ir nests and eggs (with certain exceptions) are protected under<br />

Section 1 of <strong>the</strong> Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981 as amended. This makes it an<br />

offence to:<br />

Intentionally kill, injure or take any wild bird.<br />

Intentionally damage or destroy <strong>the</strong> nest of any wild bird while that nest is in use<br />

or being built.<br />

<br />

<br />

Intentionally take or destroy <strong>the</strong> egg of any wild bird.<br />

Possess or control any live or dead wild bird or any part of, or anything derived<br />

from a wild bird, or an egg or any part of <strong>the</strong> same.<br />

Offences against Schedule 1 species carry special penalties if convicted. Schedule 1<br />

is, however, divided into two parts – birds included within part I are specially<br />

protected at all times; and those species listed in part II are protected by <strong>the</strong> same<br />

penalties but only within <strong>the</strong> closed season (1 February – 31 August).<br />

10.1.6 Current factors affecting this species<br />

Loss of nesting habitat<br />

A reduction in available food sources<br />

Persecution<br />

10.1.7 <strong>Action</strong>s<br />

Breeding bird surveys to be carried out be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> building of a new path.<br />

Where possible, <strong>the</strong> use of sympa<strong>the</strong>tic hedgerow management (e.g. hedge<br />

laying, coppicing, gapping up, replanting and less trimming) will be employed and<br />

promoted.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

24

Where planting is required in hedges, native seed and berry bearing species will<br />

be used to benefit <strong>the</strong> local bird population.<br />

Where appropriate, in<strong>for</strong>mation on <strong>the</strong> local bird life will be included in any<br />

interpretation.<br />

10.2 Bats Chiroptera<br />

10.2.1 Description<br />

There are sixteen species of bat recorded as breeding in <strong>the</strong> UK. They utilise a wide<br />

variety of structures, both natural and man-made <strong>for</strong> roosting, including trees,<br />

buildings and bridges. All need warm breeding sites in <strong>the</strong> summer and cool,<br />

undisturbed hibernation sites in <strong>the</strong> winter.<br />

10.2.2 Optimum survey time<br />

Although bats can be surveyed <strong>for</strong> throughout <strong>the</strong> year, <strong>the</strong> optimum time is from<br />

April through to early October as this is when <strong>the</strong>y are most active. It is important to<br />

remember that bats hibernate throughout <strong>the</strong> winter and <strong>the</strong>y should not be disturbed<br />

when in <strong>the</strong>ir hibernation roosts as this may cause <strong>the</strong>m to use up valuable energy<br />

reserves. See <strong>the</strong> table below <strong>for</strong> more in<strong>for</strong>mation on when and where different bat<br />

species may be encountered throughout <strong>the</strong> year.<br />

10.2.3 Current status<br />

Their current status and known distribution is summarised in <strong>the</strong> table below.<br />

Species<br />

Greater<br />

horseshoe<br />

Rhinolophus<br />

ferrumequinum<br />

Lesser<br />

horseshoe<br />

Rhinolophus<br />

hipposideros<br />

Whiskered<br />

Myotis<br />

mystacinus<br />

Brandt’s<br />

Myotis brandtii<br />

Natterer’s<br />

Myotis nattereri<br />

Bechstein<br />

Myotis<br />

bechsteinii<br />

Daubenton<br />

Myotis<br />

daubentonii<br />

Serotine<br />

Eptesicus<br />

serotinus<br />

Noctule<br />

Nyctalus noctula<br />

Summer<br />

roosts<br />

Old,<br />

undisturbed<br />

buildings<br />

Old,<br />

undisturbed<br />

buildings<br />

Trees and<br />

older<br />

buildings<br />

Trees and<br />

older<br />

buildings<br />

Trees and<br />

older<br />

buildings<br />

Hibernation<br />

roosts<br />

Caves, mines,<br />

cellars<br />

Caves, mines<br />

and cellars<br />

Caves, tunnels<br />

and mines<br />

Caves, tunnels<br />

and mines<br />

Caves, mines<br />

and cellars<br />

Feeding habitat Distribution Status<br />

Pasture and seminatural<br />

woodland<br />

Deciduous woodland<br />

Parkland, woodland<br />

and gardens<br />

Parkland, woodland<br />

and gardens<br />

Tree canopies<br />

Trees Trees Closed canopy<br />

woodland<br />

Bridges<br />

Older<br />

buildings<br />

Buildings<br />

and trees<br />

Caves, mines<br />

and ice<br />

houses<br />

Buildings<br />

Trees<br />

Over water<br />

Pasture, parkland<br />

and along woodland<br />

edges<br />

Parkland, pasture,<br />

woodland and water<br />

South west<br />

England and west<br />

Wales<br />

South west<br />

England and<br />

Wales<br />

England, Wales<br />

and South<br />

Scotland<br />

North and west<br />

England<br />

Throughout<br />

Britain<br />

South and west<br />

England and<br />

Wales<br />

Throughout<br />

England<br />

Central, south and<br />

south east<br />

England<br />

England, Wales<br />

and sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Scotland<br />

Endangered<br />

Endangered<br />

Local<br />

Local<br />

Fairly<br />

common<br />

Very rare<br />

Fairly<br />

common<br />

Locally<br />

abundant<br />

Uncommon<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

25

Leisler’s<br />

Nyctalus leisleri<br />

Common<br />

pipistrelle<br />

Pipistrellus<br />

pipistrellus<br />

Soprano<br />

pipistrelle<br />

Pipistrellus<br />

pygmaeus<br />

Nathusius<br />

pipistrelle<br />

Pipistrellus<br />

nathusii<br />

Barbastelle<br />

Barbastella<br />

barbastellus<br />

Brown longeared<br />

Plecotus<br />

auritus<br />

Grey long-eared<br />

Plecotus<br />

austriacus<br />

Trees Trees Open habitat, over<br />

water or pasture<br />

New<br />

buildings<br />

New<br />

buildings<br />

Buildings or<br />

trees<br />

Buildings or<br />

trees<br />

Woodland, grassland<br />

and over water<br />

Habitats over water<br />

South and east<br />

England, rare in<br />

Wales<br />

Throughout<br />

Britain<br />

Throughout<br />

Britain<br />

Unknown Unknown Unknown Throughout<br />

Britain<br />

Trees Trees Hedgerows and<br />

woodland<br />

Houses,<br />

churches<br />

and barns<br />

Old<br />

buildings<br />

and barns<br />

Caves and<br />

mines<br />

Caves and<br />

mines<br />

Woodland<br />

Grassland and<br />

woodland edges<br />

England and<br />

Wales<br />

Throughout<br />

Britain<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn England<br />

Rare, but<br />

widespread<br />

Common<br />

Common<br />

Becoming<br />

more<br />

common<br />

Rare<br />

Common<br />

Very rare<br />

10.2.4 Status in relation to <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

Bats could be encountered feeding, roosting and commuting along <strong>the</strong> entire length<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong> <strong>Network</strong>. It is likely that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong> <strong>Network</strong> provides important<br />

commuting routes <strong>for</strong> bats. Many bat species roost in bridges, tunnels and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

similar structures. It is <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e important that <strong>the</strong> appropriate survey work be carried<br />

out be<strong>for</strong>e work occurs on such structures.<br />

10.2.5 Legislation<br />

In England, Scotland and Wales, all bat species are fully protected under <strong>the</strong> Wildlife<br />

and Countryside Act 1981 as amended, and <strong>the</strong> Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.)<br />

Regulations 1994. All bat species are listed on Appendix III of <strong>the</strong> Bonn Convention<br />

and all except <strong>the</strong> common and soprano pipistrelles are included on Appendix II of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Bern Convention.<br />

10.2.6 Current factors affecting <strong>the</strong> species<br />

Loss of suitable breeding and hibernation sites.<br />

Loss of feeding habitats.<br />

Reduction in prey availability due to unsympa<strong>the</strong>tic farming practices.<br />

Increase in predation by cats.<br />

10.2.7 <strong>Action</strong>s<br />

Carry out surveys along proposed new routes prior to development, with<br />

particular emphasis on structures which may be used <strong>for</strong> roosting e.g. bridges and<br />

tunnels.<br />

Use bat boxes along routes where applicable.<br />

Participate in <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> Monitoring Schemes (BCT).<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r research into <strong>the</strong> importance of feeding under bridges along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

Research into <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> as commuting corridors <strong>for</strong> bats.<br />

Research <strong>the</strong> use of bridges, tunnels and o<strong>the</strong>r structures along <strong>the</strong> <strong>Network</strong> by<br />

roosting bats.<br />

In<strong>for</strong>mation about bats to be included in interpretation where appropriate.<br />

<strong>Sustrans</strong>’ <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (December 2007)<br />

26

10.3 Badger Meles meles<br />

10.3.1 Description<br />

The badger is probably Britain’s most well known mammal, with its distinctive black<br />

and white face markings making it impossible to confuse. Badgers are nocturnal and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e rarely seen during <strong>the</strong> day. When inactive, badgers usually lie-up in a<br />

system of underground tunnels and chambers known as a sett. They live in social<br />

groups and each generally produces just one litter of two or three cubs in February.<br />

Although rarely seen, badgers leave a wide variety of field signs including <strong>the</strong> sett,<br />

which is recognised by having entrances approximately 300mm wide and 200mm<br />

high, often with piles of soil outside <strong>the</strong>m, ‘snuffle holes’ (holes dug by badgers when<br />

searching <strong>for</strong> invertebrates), ‘dung pits’ (small pits in which <strong>the</strong>y deposit <strong>the</strong>ir faeces)<br />

and day nests (nests of bedding material made by badgers <strong>for</strong> sleeping above<br />

ground).<br />

10.3.2 Optimum survey time<br />

Badgers can be surveyed <strong>for</strong> throughout <strong>the</strong> year, with <strong>the</strong> optimum time being<br />

February/March when <strong>the</strong>y are very territorially active and be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> vegetation regrows,<br />

which can make surveying difficult.<br />

10.3.3 Current status<br />

The badger has a widespread distribution throughout <strong>the</strong> UK. Although badger<br />

populations are considered to be stable, various pressures have led to reductions in<br />

local populations, and in some cases extinction from areas. Badgers are not a UK<br />

BAP priority species.<br />

10.3.4 Status in relation to <strong>Sustrans</strong><br />

Badgers may be encountered throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sustrans</strong> <strong>Network</strong>. They particularly like<br />