View PDF - Swinburne University of Technology

View PDF - Swinburne University of Technology

View PDF - Swinburne University of Technology

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

www.swinburne.edu.au<br />

Diabetes hope P7<br />

Solar energy powers on P12<br />

Issue 6 | June 2009<br />

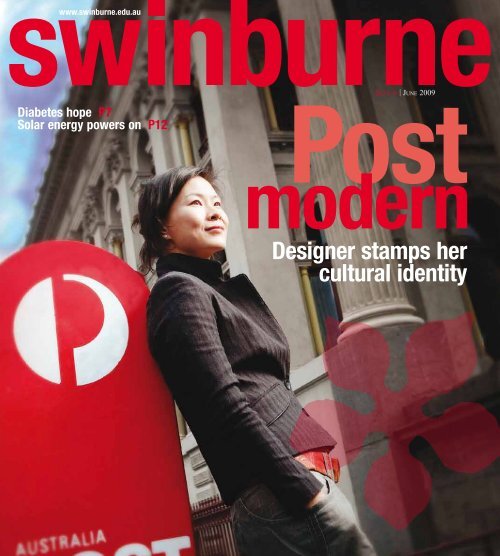

Post<br />

modern<br />

Designer stamps her<br />

cultural identity

www.swinburne.edu.au<br />

Contents<br />

Issue 6 | June 2009<br />

Diabetes hope P7<br />

Solar energy powers on P12<br />

Post<br />

ISSUE 6 | JUNE 2009<br />

modern<br />

Designer stamps her<br />

cultural identity<br />

06<br />

10<br />

swinburne JUne 2009<br />

Swin_0906_p01-24.indd 1 15/05/09 3:33 PM<br />

Upfront<br />

2<br />

Collaboration is the currency<br />

in our knowledge-based economy<br />

Australia’s economic prosperity rests on the important contributions<br />

made by Australian universities – a point highlighted in recent reviews<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Australian Innovation System and higher education. Without<br />

creating knowledge and developing innovative minds we will not thrive<br />

in the 21st century.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> is a hands-on partner in striving<br />

for answers to future challenges, by making our graduates knowledgeready<br />

and flexible and by creating new knowledge. Our ability to<br />

generate and accumulate wisdom through groundbreaking and relevant<br />

research is vital. Furthermore, <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s strategic focus has ensured<br />

that this research is recognised as genuinely world-class.<br />

As a dual-sector (TAFE to PhD) institution we are central to the<br />

‘knowledge economy’. Through TAFE we develop the next generation<br />

<strong>of</strong> competency-skilled workers, able to adapt to the rapidly changing<br />

demands <strong>of</strong> the modern workplace. Our Higher Education degree<br />

students develop their expertise and knowledge in a research-intensive<br />

environment. Learning from active, world-class researchers enables our<br />

students to further develop their capacity for independent thought and<br />

innovation. ‘Question Everything’ is heartfelt at <strong>Swinburne</strong> and built into<br />

every undergraduate’s program and consequent outcomes.<br />

Of course, new knowledge is <strong>of</strong> little value unless it is shared and<br />

put to work.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> is the acknowledged home <strong>of</strong> industry-based learning<br />

and this connection to industry flows though to our research and<br />

researchers. For example, <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s participation in the Cooperative<br />

Research Centres (CRC) program – a government-sponsored scheme<br />

that links industry with research providers – is more than double that<br />

usually expected for an institution <strong>of</strong> its size.<br />

We understand that development <strong>of</strong> knowledge in the 21st century<br />

relies on genuine effective partnerships between universities and those<br />

in the position to put that information to best use.<br />

Effective partnerships and collaborations are apparent in many <strong>of</strong> the<br />

articles in this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Swinburne</strong> magazine. I hope in reading about some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the exciting research and achievements you too can start thinking about<br />

how we can work together to lift Australia’s economic and social capacities.<br />

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research) Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Andrew Flitman<br />

cover story<br />

18 Dani’s journey<br />

across big art on a<br />

small canvas<br />

Born in China and raised<br />

in Hong Kong, Dani Poon<br />

travelled nervously to<br />

Melbourne as a 17-year-old<br />

to stamp Australian art into<br />

her destined way<br />

<br />

Features<br />

Kellie Penfold<br />

03 cloud riders to be the<br />

envy <strong>of</strong> web surfers<br />

<br />

Richard Constantine<br />

04 from the minds<br />

<strong>of</strong> babes a key to<br />

understanding ... us<br />

Australia’s first cognitive<br />

neuroscience ‘baby laboratory’<br />

is hoping to learn how infantile<br />

thoughts and gestures mature<br />

into deliberate action; how the<br />

human brain develops and<br />

sometimes fails<br />

<br />

rebecca thyer<br />

06 Diabetes hope on the<br />

wings <strong>of</strong> silver cicadas<br />

The wings <strong>of</strong> a familiar noisy<br />

insect, the cicada, were the<br />

starting point for a device that will<br />

be able to continuously monitor<br />

blood glucose levels<br />

<br />

Penny Fannin<br />

09 Alloy research cuts<br />

through the fighter<br />

cost barrier<br />

<br />

rebecca thyer<br />

10 All power to the sun<br />

and the light team<br />

Affordable solar power may soon<br />

be just a flick <strong>of</strong> the switch away<br />

<br />

robin taylor<br />

12 Companies find a<br />

competitive green edge<br />

A business environmental<br />

mentoring program is showing<br />

that ‘going green’ can win<br />

customers and pr<strong>of</strong>its<br />

<br />

robin taylor<br />

14 No joke when it’s<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> the funniest<br />

Bianca Nogrady & Rebecca Thyer<br />

15 New environment to<br />

debug global-scale IT<br />

upgrades david adams<br />

16 Dark mysteries lure<br />

cosmic surveyors<br />

A massive survey <strong>of</strong> the universe<br />

is under way in Australia to detect<br />

the faintest <strong>of</strong> echoes: an acoustic<br />

‘wiggle’ from the Big Bang. A<br />

wiggle that may hold the key to<br />

understanding a mysterious new<br />

force – dark energy – that is<br />

causing the universe to fly apart<br />

<br />

Gio Braidotti<br />

20 Digital dust-<strong>of</strong>f for<br />

history’s watchhouses<br />

<br />

Julian Cribb<br />

21 Will the ferryman come<br />

for climate refugees?<br />

<br />

robin taylor<br />

22 A modern-day oracle<br />

on the ocean waves<br />

Like gypsies read tea leaves to<br />

foresee the future, researchers<br />

can read something <strong>of</strong> our future<br />

in the winds and waves. However,<br />

this modern soothsaying relies on<br />

masses <strong>of</strong> information – data that<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> is collating to build the<br />

world’s first complete picture <strong>of</strong><br />

ocean wave activity<br />

<br />

Julian Cribb<br />

•• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• ••<br />

12<br />

16<br />

Published by <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

Editor: Dorothy Albrecht, Director, Marketing Services<br />

Deputy editor: Julianne Camerotto, Communications Manager<br />

(Research and Industry), Marketing Services<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>, Melbourne<br />

Written, edited, designed and produced on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> by Coretext, www.coretext.com.au, 03 9670 1168<br />

Enquiries: 1300 MY SWIN (1300 697 946)<br />

Website: www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Email: magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

Cover photo: Dani Poon photographed by Paul Jones<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> collects and uses your information in accordance with our<br />

Privacy Statement, which can be found at: www.swinburne.edu.au/privacy.<br />

If you do not wish to receive communications from us, you can email privacyoptout@swinburne.edu.au,<br />

fax (03) 9214 8447, or write to <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>, Privacy at <strong>Swinburne</strong>,<br />

PO Box 218, Hawthorn VIC 3122.<br />

The information contained in this publication was correct at the time <strong>of</strong> going to press, June 2009.<br />

CRICOS provider Code 00111D<br />

ISSN 1835-6516 (Print)<br />

ISSN 1835-6524 (Online)

June 2009 swinburne<br />

Cloud riders<br />

to be the envy <strong>of</strong> web surfers<br />

essay by Richard Constantine*<br />

A quick scan <strong>of</strong> the daily newspaper shows<br />

just how much data-driven information<br />

is being produced these days and how<br />

everyone, from decision-makers in business<br />

and government to scientists and researchers,<br />

is drawing on ever-increasing volumes <strong>of</strong><br />

data to try to solve problems.<br />

However, good decision-making requires<br />

more than just great volumes <strong>of</strong> data, no matter<br />

how accurate and up-to-date it is. Data has to<br />

be carefully mined for the right information,<br />

for the gold to be sifted from the gravel.<br />

Nowhere is data volume more a quality<br />

assurance (QA) issue than at universities,<br />

where researchers, by the very nature <strong>of</strong> their<br />

job, are confronted with vast quantities <strong>of</strong><br />

data from electronic sensors, all manner <strong>of</strong><br />

measuring tools, analytical equipment and<br />

myriad other information streams.<br />

The data that is stored and processed then<br />

forms part <strong>of</strong> a network <strong>of</strong> ‘information banks’,<br />

increasingly accessible to researchers and other<br />

users via the internet. While proximity to an<br />

information bank is no longer an issue, the<br />

ability to access and process information from<br />

any location is still a problem.<br />

The new era that is emerging is ‘cloud<br />

computing’, which allows people to access<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tware applications and their own files<br />

using any internet-connected computer,<br />

anywhere, at any time.<br />

An analogy is the provision <strong>of</strong> essential<br />

services such as electricity, water and gas. The<br />

generation and distribution <strong>of</strong> these services<br />

occurs <strong>of</strong>f-site and the consumer simply needs<br />

to ‘plug in’ to the services concerned to have<br />

them delivered down the line.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> the major IT organisations, such<br />

as IBM, Cisco Systems, Dell, Symantec,<br />

Sun Microsystems, HP and Facebook, as<br />

well as many small organisations, have<br />

already developed their own dedicated<br />

cloud computing divisions to organise the<br />

development, marketing and sales <strong>of</strong> hardware,<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tware and services in this burgeoning area.<br />

Micros<strong>of</strong>t, Google and others have developed<br />

a range <strong>of</strong> web-based applications and,<br />

importantly, web-based storage.<br />

At universities like <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>, students and staff are now<br />

expecting a more flexible and dynamic<br />

IT environment that will cater for them<br />

in moving between campuses, including<br />

photo: paul Jones<br />

<strong>of</strong>fshore campuses, and other locations.<br />

Telecommuting, for part <strong>of</strong> the week at<br />

least, is now a more viable option for many<br />

university staff. Applications such as learning<br />

management systems, student administration<br />

systems, human resources and finance<br />

systems, to name a few, need to be available<br />

anywhere at anytime. Cloud computing or<br />

delivery via the internet is shaping as the<br />

answer to this increasing need for mobility.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> the basic requirements for<br />

effective cloud computing are already in<br />

place, such as sufficient bandwidth with<br />

reliable, high-speed connectivity and a range<br />

<strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>tware applications already available via<br />

the web.<br />

According to the Australian Bureau<br />

<strong>of</strong> Statistics, 67 per cent <strong>of</strong> Australian<br />

households have home internet access and,<br />

<strong>of</strong> these, more than 43 per cent are highspeed<br />

broadband users. It is likely that the<br />

Australian online experience would be<br />

similar to that in America, where research<br />

undertaken through the Pew Research<br />

Center’s ‘Internet & American Life’ project<br />

has shown that 69 per cent <strong>of</strong> Americans<br />

online now use cloud computing activities.<br />

While the fog is starting to lift to reveal<br />

the true form <strong>of</strong> the cloud, there are still<br />

blurred patches. The most critical element<br />

that is yet to be resolved relates to the remote<br />

storage <strong>of</strong> corporate data. It raises obvious<br />

questions about security, privacy, intellectual<br />

property and reliability <strong>of</strong> access.<br />

Who has jurisdiction over data stored<br />

in remote locations? Do we know what is<br />

happening behind the service boundary?<br />

Who is in control? What processes are in<br />

place to guarantee access to critical data or<br />

files as and when needed? It behoves us all<br />

to ensure that governance arrangements and<br />

contract terms relating to service delivery,<br />

including how the services are accessed, are<br />

fully researched and resolved.<br />

A recent detailed study <strong>of</strong> cloud computing<br />

by the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> California, Berkeley, has<br />

worked through these issues and identified a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> potential solutions, such as having<br />

multiple cloud-computing providers to ensure<br />

the availability <strong>of</strong> service and access to<br />

critical data. While the authors recognise the<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> clarity at the present time they are still<br />

optimistic for the future <strong>of</strong> cloud computing.<br />

Despite the issues to be resolved, most<br />

indications suggest that it will not be too<br />

long before we won’t just be surfing the<br />

web, we’ll be riding the cloud. ••<br />

* Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Richard Constantine<br />

is <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>’s<br />

Chief Information Officer.<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 MY SWIN (1300 697 946)<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Richard Constantine<br />

Cloud computing<br />

‘Cloud computing’ allows<br />

people to access s<strong>of</strong>tware<br />

applications and their own<br />

files using any internetconnected<br />

computer,<br />

anywhere, at any time.<br />

Commentary<br />

3

swinburne June 2009<br />

neuroscience<br />

4<br />

Australia’s first cognitive neuroscience ‘baby laboratory’ is hoping to learn how<br />

infantile thoughts and gestures mature into deliberate action; how the human brain<br />

develops and sometimes fails By Rebecca Thyer

June 2009 swinburne<br />

Sitting on her mother’s lap with a tiny,<br />

Velcro-covered mitten covering her 11-weekold<br />

hand, Molly reaches for an object that<br />

is similarly covered in Velcro. It’s a simple<br />

move that defies what other babies her age<br />

typically do, which is how young Molly<br />

is helping researchers better understand<br />

developing brain activity.<br />

As a ‘baby scientist’ Molly is helping<br />

researchers at <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong>’s Brain Science Institute<br />

learn more about a process called mirror<br />

neuron activity – where the brain mirrors<br />

the activity <strong>of</strong> another person, activating a<br />

neuron response, even though no physical<br />

movement occurs.<br />

Leading the work is Dr Jordy Kaufman,<br />

who moved to Melbourne from the <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> London, Birkbeck, to establish the<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> Baby Laboratory in early 2008.<br />

Dr Kaufman says Molly’s involvement in<br />

the lab’s ‘Sticky Mittens’ project is allowing<br />

researchers to explore brain development.<br />

“At three months old babies are not good at<br />

reaching for things, but with practice they<br />

can do something like it. It may look like<br />

they are just swiping or swatting at things,<br />

but they are trying to get the toy.”<br />

Previous US-led research has shown that<br />

babies with ‘sticky mitten’ experience take<br />

more <strong>of</strong> these bold, directive actions – that is,<br />

they grab at objects more than other babies.<br />

Sticky mitten research began about a<br />

decade ago with Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Amy Needham,<br />

who supervised Dr Kaufman’s PhD in her<br />

previous role at Duke <strong>University</strong>.<br />

Now at the Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology<br />

and Human Development at Nashville’s<br />

Vanderbilt <strong>University</strong>, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Needham<br />

says these types <strong>of</strong> projects help to build<br />

an understanding <strong>of</strong> infant motor skill<br />

development and the changes behind it.<br />

“Development is a complex phenomenon<br />

and we are only now starting to understand<br />

the many ways in which different processes<br />

influence each other as development takes<br />

place,” she says.<br />

Perhaps most importantly for those who<br />

are exploring brain development, is that<br />

babies with a sticky mitten experience also<br />

watch the actions <strong>of</strong> others more closely.<br />

And by carefully watching the actions <strong>of</strong><br />

others, there is the possibility <strong>of</strong> enhanced<br />

brain development, allowing infants to better<br />

interpret other people’s actions.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Dr Kaufman says his sticky<br />

mitten research will monitor this. “We want<br />

to know if giving babies a sticky mitten<br />

experience leads them to show more mirror<br />

neuron activity than those without.”<br />

To answer this question, Dr Kaufman<br />

is studying the brain waves <strong>of</strong> two sets <strong>of</strong><br />

babies: those like Molly who have sticky<br />

mitten experience and those without. In both<br />

cases babies watch their parent grab for an<br />

object while their brain waves are monitored.<br />

“We are essentially finding out more about<br />

the mind’s building blocks.”<br />

The <strong>Swinburne</strong> Baby Laboratory monitors<br />

these brain waves using a non-invasive<br />

electroencephalogram (EEG). It works<br />

in much the same way as a thermometer<br />

measures temperature. A net <strong>of</strong> 128 sensors<br />

is placed over a baby’s head to measure<br />

naturally occurring brain activity. The sensors<br />

capture the electrical signals coming from the<br />

brain while the baby watches objects or listens<br />

to sounds. Dr Kaufman says it is a completely<br />

safe experience for the babies involved and<br />

usually lasts between two and 15 minutes.<br />

The work could also have commercial<br />

ramifications. Dr Andy Bremner, a former<br />

colleague <strong>of</strong> Dr Kaufman’s from the<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> London, Goldsmiths, says<br />

that because sticky mitten research may<br />

help to explain how active exploratory<br />

experiences drive development, it could<br />

provide toy manufacturers with evidence that<br />

certain educational products are beneficial.<br />

“Currently there is little evidence basis for<br />

any benefit <strong>of</strong> such toys, but this research<br />

could help to provide this.”<br />

That aside, Dr Kaufman says what<br />

drives the <strong>Swinburne</strong> Baby Laboratory is<br />

the ability to provide insight into the minds<br />

<strong>of</strong> infants and young children. Its work has<br />

important ramifications for learning about the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> autism and schizophrenia.<br />

“Understanding how these conditions develop<br />

could lead to more sensitive diagnostic<br />

measures, and therefore earlier intervention.”<br />

One way <strong>of</strong> doing this is to measure how<br />

babies’ brains react to changes in sound, a<br />

perceptual process called ‘change detection’,<br />

Lab delves into our infancy<br />

The <strong>Swinburne</strong> Baby Laboratory is Australia’s first cognitive neuroscience<br />

facility for babies and infants.<br />

It was established in early 2008 by Dr Jordy Kaufman, who became<br />

interested in studying brain development when he undertook a cognitive<br />

science degree at Carnegie Mellon <strong>University</strong> and a PhD at Duke<br />

<strong>University</strong> with Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Amy Needham. His interest then led him to<br />

the UK to work with Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Mark Johnson at the Centre for Brain and<br />

Cognitive Development at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> London, Birkbeck.<br />

He wants to find out how the mental world <strong>of</strong> infants differs from that<br />

<strong>of</strong> adults.<br />

“We are more infantile than we think,” he says. “Only 10 to 15 per<br />

cent <strong>of</strong> things we do now are different from what we did then. Yet, the<br />

relationship between brain development and cognitive development in<br />

babies is largely unknown.”<br />

What drives Dr Kaufman is the desire to give scientists and parents<br />

alike a window into this world from which we have all grown. “Almost<br />

all parents at some point wonder what it is that their baby can see, hear,<br />

feel, remember and understand. The <strong>Swinburne</strong> Baby Laboratory was<br />

created to help answer these questions,” he says.<br />

More information<br />

• If you are a parent <strong>of</strong> a baby or child up to 5 years old, you can take part in<br />

research at the <strong>Swinburne</strong> Baby Laboratory by emailing babylab@swin.edu.au<br />

or visiting www.babylab.org<br />

The more we know about the typically<br />

developing brain, the more scientists can<br />

discover markers for atypical development.<br />

which forms the basis <strong>of</strong> another <strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

Baby Laboratory project. “Basically this<br />

means we play some sounds and then change<br />

it and see what their brain waves do.<br />

“We know how adults’ brains respond<br />

to auditory change – even in our sleep our<br />

brains are aware <strong>of</strong> any changes in noise –<br />

but do babies respond?”<br />

Finding out if babies do respond to<br />

auditory change could lead to a better<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> how autism and<br />

schizophrenia develop. For example, people<br />

with schizophrenia do not show the same<br />

level <strong>of</strong> change detection as those without<br />

it; and some people with autism are highly<br />

sensitive to auditory change.<br />

“So by monitoring how the brain develops<br />

we might gain more insight into this,”<br />

Dr Kaufman says. “The more we know<br />

about the typically developing brain, the<br />

more scientists can discover markers for<br />

atypical development, perhaps leading to<br />

early diagnostic tests and early interventions<br />

to minimise the negative effects <strong>of</strong> atypical<br />

brain development.” ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 MY SWIN (1300 697 946)<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

neuroscience<br />

5

swinburne June 2009<br />

new technologies<br />

6

June 2009 swinburne<br />

,,<br />

The passive end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the fibre light<br />

guide can be<br />

rigidly mounted<br />

for accurate<br />

alignment with<br />

the laser, while<br />

the sensing<br />

end can remain<br />

flexible to make<br />

contact with<br />

the sample. In<br />

this way the<br />

sensor can<br />

be packaged<br />

into a thin,<br />

flexible needle<br />

and inserted<br />

beneath the skin<br />

with minimal<br />

discomfort.”<br />

Dr Paul Stoddart<br />

illustration: Justin garnsworthy<br />

Browsing the research posters at<br />

a scientific conference in 2002, Paul<br />

Stoddart was taken aback. Before him was<br />

an electron micrograph <strong>of</strong> a cicada wing<br />

that showed line after line <strong>of</strong> microscopic<br />

pillars arrayed on the wing’s surface, a<br />

pattern that resembled just the nanostructure<br />

Dr Stoddart was looking for to improve the<br />

sensitivity <strong>of</strong> a spectroscopy technique he<br />

was using.<br />

That chance sighting led Dr Stoddart, a<br />

research fellow at <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong>, to spend many days searching<br />

suburban scrub for cicadas, removing their<br />

wings and coating them with silver. This<br />

was no amateur nature experiment; it was a<br />

means <strong>of</strong> refining an optical fibre sensor that<br />

would allow the continuous monitoring <strong>of</strong><br />

blood glucose levels in humans.<br />

“When I saw these patterns <strong>of</strong> structure<br />

on the cicada wings I thought they could be<br />

<strong>of</strong> some interest to the sensor application.<br />

So I coated a wing with silver and found it<br />

produced excellent results,” Dr Stoddart says.<br />

“The wings have an anti-reflection<br />

coating to prevent them reflecting sunlight<br />

and enhancing their camouflage. It turns<br />

out that this type <strong>of</strong> anti-reflective coating<br />

is exactly the kind <strong>of</strong> nanostructure suitable<br />

for the spectroscopy technique – Surface<br />

Enhanced Raman Scattering – that we use.<br />

“The wing surface provides a scale <strong>of</strong><br />

roughness that is ideally suited to our needs.<br />

When laser light illuminates the roughened<br />

surface, which has been coated in silver<br />

or gold, the light interacts with the surface<br />

electrons in such a way that the Raman<br />

scattering (the scattering <strong>of</strong> light photons) is<br />

increased by a factor <strong>of</strong> a million … in other<br />

words there is an amplification effect.”<br />

Further, the particular ordered, pillarpattern<br />

<strong>of</strong> the cicada wings adds a regularity<br />

that allows the results to be replicated more<br />

accurately.<br />

Dr Stoddart and colleagues at <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s<br />

Centre for Atom Optics and Ultrafast<br />

Spectroscopy are using Surface Enhanced<br />

Raman Scattering in the development <strong>of</strong> a<br />

device that will constantly monitor blood<br />

glucose levels in people with diabetes.<br />

The research team has developed and<br />

patented an optical fibre probe that could<br />

Diabetes hope<br />

on the wings <strong>of</strong><br />

silver cicadas<br />

The wings <strong>of</strong> a familiar noisy insect, the cicada, were the<br />

starting point for a device that will be able to continuously monitor<br />

blood glucose levels By Penny Fannin<br />

be used to monitor people’s blood glucose<br />

levels in real time, instead <strong>of</strong> the periodic<br />

tests diabetics must self-administer through<br />

the course <strong>of</strong> each day. The probe fits inside<br />

a small-gauge needle and Dr Stoddart<br />

envisages both would be incorporated into<br />

a wristwatch-style device. “The watch<br />

would contain the laser and the optics and<br />

the needle, with its fibre sensor, would be<br />

plugged in.” With one end <strong>of</strong> the needle<br />

plugged in to the device the other would<br />

penetrate the skin.<br />

Crucial to the success <strong>of</strong> such a device is<br />

finding a way for the glucose in the blood to<br />

interact with the sensor, Dr Stoddart says.<br />

“These optical fibres are the diameter<br />

<strong>of</strong> a hair and at the top <strong>of</strong> the hair we are<br />

building this sensor device,” he says. “For<br />

the sensing technique to work the optical<br />

fibre needs to have a nanostructured metal<br />

surface, preferably gold or silver, on its<br />

tip,” he says. “The metal surface interacts<br />

with the light passing through the optical<br />

fibre and amplifies the signal returned from<br />

the glucose by Surface Enhanced Raman<br />

Scattering.” The signal is then translated<br />

into a blood glucose reading through a<br />

spectrum analyser that is built in to the<br />

device.<br />

“The fact that it’s an optical fibre sensor<br />

is important because it removes the difficulty<br />

<strong>of</strong> otherwise aligning a focused laser beam<br />

with the sensor surface,” Dr Stoddart says.<br />

“The passive end <strong>of</strong> the fibre light<br />

guide can be rigidly mounted for accurate<br />

alignment with the laser, while the sensing<br />

end can remain flexible to make contact<br />

with the sample. In this way the sensor can<br />

be packaged into a thin, flexible needle<br />

and inserted beneath the skin with minimal<br />

discomfort.”<br />

Traditionally, optical fibre sensors have<br />

been used for industrial applications such<br />

as monitoring temperatures in oil wells,<br />

new technologies<br />

7

swinburne june 2009<br />

new technologies<br />

8<br />

Optical fibres help hearing surgeons ‘see’<br />

Cochlear implants, or bionic ears, have dramatically improved the hearing <strong>of</strong><br />

more than 150,000 people worldwide. However, in a small number <strong>of</strong> cases,<br />

the process <strong>of</strong> implanting the device can damage the delicate structures<br />

inside the cochlea (the snail-shaped structure in the inner ear that contains<br />

the organ <strong>of</strong> hearing).<br />

At a trade show in 2007 Dr Paul Stoddart, a research fellow at<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Centre for Atom Optics and Ultrafast Spectroscopy, met<br />

representatives from Australian cochlear implant manufacturer Cochlear<br />

Ltd and began discussing the potential for optical fibre sensing devices to<br />

prevent potential tissue damage during cochlear implantation.<br />

“There might be some residual hearing left, so it would be better if the<br />

surgeons could tell, during implantation, if they were pushing up against the<br />

fine internal cochlea structures,” Dr Stoddart says.<br />

Cochlear’s head <strong>of</strong> implant design and development Edmond Capcelea<br />

says it is important to minimise any potential trauma to the internal cochlea<br />

structures during implantation.<br />

“Minimising trauma at insertion is really worthwhile,” he says. “Right<br />

now this procedure is done without direct feedback in terms <strong>of</strong> insertion <strong>of</strong><br />

the electrode array into the cochlea. Direct, instant feedback during insertion<br />

is preferable to lagging feedback, such as from patient performance.<br />

“This development we’re running with <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong> is part <strong>of</strong> our drive to develop smarter or superior electrode<br />

arrays whereby the surgeons can get clues on whether they are touching the<br />

delicate internal cochlea tissue during insertion <strong>of</strong> the electrode array.”<br />

In collaboration with Cochlear, Dr Stoddart is investigating putting optical<br />

fibre Bragg gratings into the electrode array <strong>of</strong> cochlear implants where they<br />

could be used to guide the insertion <strong>of</strong> the array by the surgeon.<br />

“Optical fibre Bragg gratings were first used in the telecommunications<br />

industry to make optical fibre components, but the fibres can also be used<br />

for sensing,” Dr Stoddart says.<br />

Fibre Bragg gratings can be constructed in an optical fibre where they<br />

reflect particular wavelengths <strong>of</strong> light and transmit others. “If you stretch the<br />

fibre it can reflect longer wavelengths and if you compress it you can reflect<br />

shorter wavelengths so it is a good strain sensor,” Dr Stoddart says.<br />

“This is a very neat way <strong>of</strong> making an optical fibre filter without using<br />

discrete elements; everything can be done in the optical fibre.”<br />

Dr Stoddart says the research aims to put an optical fibre Bragg grating<br />

in the electrode array <strong>of</strong> cochlear implants where it can detect any pressure<br />

on the internal structures <strong>of</strong> the ear by monitoring a shift in the wavelength.<br />

“In due time we want to be trialling the first <strong>of</strong> these sensors in an<br />

implant. It will be a very significant development if we can get these fibres<br />

routinely used in implants.”<br />

– Penny Fannin<br />

sensing strain in bridges or in optical fibre<br />

gyroscopes in aeroplanes. Their use in<br />

medical devices is only now being widely<br />

explored.<br />

Dr Stoddart hopes the optical fibre sensor<br />

would be used as an alternative to the<br />

existing finger-prick test for measuring blood<br />

glucose levels. In this test a small lancet<br />

is used to puncture the fingertip and the<br />

resulting drop <strong>of</strong> blood is placed on a testing<br />

strip. The strip is then put in a blood glucose<br />

monitor that reads the blood sugar level.<br />

“The problem with the finger-prick test<br />

is you get snapshots <strong>of</strong> your glucose level;<br />

there might be five or six measurements<br />

per day, but you don’t know what’s<br />

happening in between those measurements,”<br />

Dr Stoddart says.<br />

“Our approach provides minimally<br />

invasive, continuous monitoring. If you<br />

want a controlled system you need to have<br />

continuous monitoring.”<br />

Dr Barry Dixon, the head <strong>of</strong> clinical<br />

research in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)<br />

<strong>of</strong> Melbourne’s St Vincent’s Hospital,<br />

says there is a clinical need for continuous<br />

glucose monitoring that is less invasive and<br />

more efficient than current methods.<br />

Critically ill patients in the ICU are<br />

medically unstable and have problems with<br />

glucose control so their glucose levels are<br />

regularly monitored, Dr Dixon says.<br />

“At the moment in the ICU we take fourhourly<br />

blood glucose measurements and<br />

then work out how much insulin we should<br />

give,” Dr Dixon says. “Our ICU is a 12-bed<br />

ICU so with 12 patients we would be doing<br />

that pretty much all the time. That adds up<br />

to a lot <strong>of</strong> blood tests and a lot <strong>of</strong> time spent<br />

measuring insulin needs.”<br />

“Long-term, I hope we can set up a<br />

continuous glucose measurement where the<br />

device goes into the skin a small distance<br />

and that, as the technology improves, the<br />

measurements will become non-invasive and<br />

can be made just with a light source.”<br />

Such a novel application for optical fibre<br />

sensors started with the Diabetes Australia<br />

Research Trust providing seed funding for<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s research. Further funding over<br />

the past five years from the National Health<br />

and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)<br />

and ASX-listed company BioPharmica Ltd<br />

(BPH) has seen the research program make<br />

significant achievements.<br />

At the moment Dr Stoddart’s device is<br />

about the size <strong>of</strong> a lunch box. Although some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the components will need to be smaller,<br />

the research focus now is on improving the<br />

stability <strong>of</strong> the sensor.<br />

He says for the glucose in the blood to<br />

absorb onto the sensor the metal surface<br />

needs to be treated with a chemical. “You<br />

need this intimate connection between<br />

the sensor and the glucose to take the<br />

measurement,” he says.<br />

Commercially available chemicals have<br />

been trialled and the research team has<br />

identified a treatment that allows detection <strong>of</strong><br />

glucose at the lowest physiological levels in<br />

which they occur in humans.<br />

“At this stage the surface treatment only<br />

lasts for some minutes, we need to improve<br />

that to several days.” Dr Stoddart says there<br />

are well-established methods <strong>of</strong> doing that<br />

but they need to be worked through.<br />

He envisages the wristwatch device would<br />

need to have its sensor replaced every few<br />

days. For this to happen the sensors need to<br />

be produced quickly and in high numbers.<br />

That’s where the cicada wings become<br />

important.<br />

Dr Stoddart, in collaboration with<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Arnan Mitchell’s group<br />

at RMIT <strong>University</strong>, has been using a<br />

technique called nanoimprint lithography to<br />

make copies <strong>of</strong> the cicada wing patterns at a<br />

nano scale. The technique involves making<br />

a mould <strong>of</strong> the wing surface and pressing<br />

it into a layer <strong>of</strong> heated plastic on the tip<br />

<strong>of</strong> an optical fibre. This creates an accurate<br />

imprinted copy <strong>of</strong> the nanoscopic pattern<br />

found on each wing. The imprinted tip can<br />

then be coated with gold or silver to make<br />

the sensor.<br />

Dr Stoddart says that when his team first<br />

used nanoimprint lithography to make the<br />

moulds about one tip an hour was being<br />

produced. “Funding from the NHMRC<br />

has allowed us to increase that by a factor<br />

<strong>of</strong> 100 and at that rate the process can be<br />

commercially viable. Because the sensors are<br />

disposable we need to be able to do that.”<br />

At current rates <strong>of</strong> progress he estimates<br />

the device would be available for trials in<br />

five years.<br />

“By developing medical applications for<br />

optical fibre sensors we can find a way to<br />

make a difference to people’s lives,” he says.<br />

“Whenever I talk about this diabetes work I<br />

ask for a show <strong>of</strong> hands from people with a<br />

family member or friend with diabetes; it’s<br />

amazing how many people put their hands<br />

up. You don’t get that when you’re working<br />

with oil wells.” ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 MY SWIN (1300 697 946)<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine

June 2009 swinburne<br />

Alloy research<br />

cuts through the fighter cost barrier<br />

story by Rebecca Thyer<br />

Defence is an expensive business. Strike<br />

aircraft weapons systems, for example,<br />

don’t come cheap. But their necessity, and<br />

these strained economic times, means more<br />

research is being put into reducing their cost<br />

<strong>of</strong> production.<br />

So what on the surface is a conventional<br />

cost-cutting exercise – to reduce titanium<br />

machining costs and improve productivity<br />

– also has important ramifications for an<br />

international military project led by the US.<br />

Run by the US Department <strong>of</strong> Defense, the<br />

Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program is looking<br />

to not only produce the next generation <strong>of</strong><br />

defence aircraft for the US military and its<br />

allies, including Australia – which has a<br />

$16 billion tentative order for 100 F-35 JSFs<br />

– but to also make them more affordable.<br />

An important aspect <strong>of</strong> achieving this is<br />

being able to reduce the cost <strong>of</strong> machining<br />

titanium alloys. Their high strength-toweight<br />

ratio, the ability to retain that strength<br />

at high temperatures, and high corrosion<br />

resistance compared with other alloys<br />

has long made this metal attractive to the<br />

aerospace, marine, chemical, petroleum and<br />

biomedical industries.<br />

However, titanium alloys are difficult<br />

to machine, even with modern cutting<br />

technology. This is due to <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong><br />

factors:<br />

the way the alloy changes shape when<br />

machined;<br />

its low thermal conductivity, which makes<br />

it difficult to remove heat from the cutting<br />

region, increasing the temperature and<br />

contributing to a chemical interaction with<br />

the cutting tool’s material; and<br />

the alloy’s low elastic modulus, which<br />

means the material is easily deformed<br />

during machining.<br />

The F-35<br />

The Royal Australian<br />

Air Force has placed a<br />

tentative order, worth<br />

$16 billion, for 100 <strong>of</strong><br />

the Lockheed Martin<br />

F-35 Lightning II joint<br />

strike fighters.<br />

The F-35 is a<br />

supersonic, multi-role,<br />

fifth-generation stealth<br />

fighter. Three variants<br />

derived from a common<br />

design, developed<br />

together and using the<br />

same infrastructure<br />

worldwide, will replace<br />

at least 13 types <strong>of</strong><br />

aircraft for 11 nations<br />

initially, making the<br />

Lightning II the most<br />

cost-effective fighter<br />

program in history.<br />

More information<br />

• www.jsf.mil<br />

Added together it means that it takes<br />

longer to machine titanium alloys compared<br />

with other metals and tools are worn out<br />

faster, resulting in high machining costs.<br />

Tackling this problem – the resolution<br />

<strong>of</strong> which would have benefits for<br />

manufacturing worldwide – is Australia’s<br />

CAST Cooperative Research Centre (CRC).<br />

The CRC, which includes <strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>, conducts industrydriven<br />

research into the use <strong>of</strong> aluminium,<br />

magnesium, titanium, cast iron and steel.<br />

Its CEO, George Collins, says the CAST<br />

CRC has been working to reduce titanium<br />

production costs for several years, and has<br />

been funding <strong>Swinburne</strong> to work on the<br />

laser-assisted turning <strong>of</strong> titanium. “It was a<br />

‘blue sky’ project for us and one <strong>of</strong> only two<br />

strategic research projects we fund. But it<br />

caught the attention <strong>of</strong> Lockheed Martin.”<br />

US-based Lockheed Martin is the global<br />

security and IT consultancy responsible for<br />

delivering on the goals <strong>of</strong> the US Defense<br />

Department’s JSF program.<br />

Dr Don Kinard, Lockheed Martin’s<br />

technical operations deputy for F-35 global<br />

production operations, says titanium alloys<br />

are widely used on the F-35 Lightning II,<br />

a strike fighter being developed by the<br />

JSF Program.<br />

“Machined and forged titanium parts are<br />

used routinely in high temperature areas such<br />

the engine compartment, where aluminium<br />

alloys cannot operate efficiently,” Dr Kinard<br />

says. “Titanium is also used in other<br />

structural F-35 applications, where it saves<br />

sufficient weight to justify the increased<br />

production cost.<br />

“For example, the use <strong>of</strong> machined/<br />

forged titanium parts is more pronounced on<br />

the F-35 carrier variant because <strong>of</strong> the high<br />

loads which that airplane encounters during<br />

carrier landings.”<br />

Interested in the results <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Milan Brandt was getting –<br />

including that lasers make it possible<br />

to quicken the turning process at the<br />

same lathe power, while improving the<br />

finished product’s surface integrity thereby<br />

maintaining its strength and corrosionresistance<br />

properties – Lockheed Martin<br />

paid a visit while in Australia touring local<br />

research capability.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Brandt says Lockheed Martin<br />

was interested in the laser-assisted turning<br />

project, but wanted to know if the same<br />

results could be gained from laser-assisted<br />

milling.<br />

It is a question that Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Brandt’s<br />

team – which includes his Industrial<br />

Research Institute <strong>Swinburne</strong> colleagues<br />

Dr Shoujin Sun, Girish Thipperudrappa,<br />

Andy Moore and PhD student Nancy Yang<br />

– is now half-way through answering via<br />

another CAST CRC project, one that is<br />

funded by Lockheed Martin.<br />

The research team uses a laser to heat<br />

the material surface, with a beam directed<br />

in front <strong>of</strong> the cutting tool, allowing the<br />

material to be cut with greater ease.<br />

Experiments vary the laser power,<br />

machining speed and depth <strong>of</strong> cut. “We<br />

want to find out why the reduction in cutting<br />

forces occurs with the heat <strong>of</strong> the laser and<br />

at what distance from the cutting tool,”<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Brandt says.<br />

So far, results for milling are as positive<br />

as those <strong>of</strong> laser-assisted turning. “But we<br />

need to do more experiments and see how<br />

we could integrate a laser and the cutting<br />

tool. That’s the long-term objective and<br />

ultimate aim <strong>of</strong> the Lockheed Martin work –<br />

to deliver the technical data needed to design<br />

an all-in-one machine.”<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Brandt says the idea to use<br />

lasers came from previous research on<br />

ceramics, another hard-to-machine material.<br />

“All we are trying to do is translate that to<br />

titanium. If we can increase the removal rate<br />

and increase tool life, then we can reduce the<br />

cost <strong>of</strong> machining and using titanium.”<br />

The research also allows for his team to<br />

examine the fundamental science behind<br />

laser-assisted titanium machining – and<br />

already Dr Sun has a new theory on titanium<br />

cutting.<br />

“At the end <strong>of</strong> the day it is all leading to<br />

machining titanium faster but maintaining a<br />

quality surface. Our objective is to increase<br />

the understanding <strong>of</strong> the cutting process and<br />

translate that into practical information.” ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 MY SWIN (1300 697 946)<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

manufacturing<br />

9

swinburne June 2009<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Min Gu is working on developing solar cells that use<br />

sunlight more efficiently and cost half as much to produce.<br />

solar power<br />

10<br />

All power<br />

to the sun and the light team<br />

PHOTO: Newspix / Paul Loughnan<br />

Affordable solar<br />

power may<br />

soon be just<br />

a flick <strong>of</strong> the<br />

switch away<br />

By<br />

Robin Taylor<br />

What began decades ago as a friendship<br />

between two university students in Shanghai<br />

has led to a multi-million-dollar research<br />

project with the potential to produce nextgeneration<br />

solar power as affordable as<br />

fossil-fuel-derived energy.<br />

The collaboration between <strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> and China-based<br />

Suntech Power – one <strong>of</strong> the world’s largest<br />

manufacturers <strong>of</strong> solar panels – aims to<br />

develop solar cells that are twice as efficient<br />

and half the cost <strong>of</strong> existing cells.<br />

If the project is successful, the new<br />

technology – which makes more efficient use<br />

<strong>of</strong> sunlight – could be on the market within<br />

five years and close the gap between solar<br />

and fossil fuels.<br />

The project is led by Suntech CEO<br />

Dr Zhengrong Shi and the head <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Centre for Micro-Photonics,<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Min Gu, and builds on a friendship<br />

that began at university and continued in<br />

Australia when they began working side-byside<br />

at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> New South Wales in<br />

the late 1980s.<br />

Since then Dr Shi’s Suntech has become<br />

the world’s largest producer <strong>of</strong> crystalline<br />

silicon solar panels, and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu a<br />

leader in micro-photonics research.<br />

Research-wise they have followed<br />

different paths while maintaining a shared<br />

interest in light: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu pursued<br />

research on laser fusion and micro-photonics<br />

and Dr Shi was part <strong>of</strong> the pioneering team<br />

that developed thin solar cell technology, a<br />

breakthrough that dramatically reduced the<br />

cost <strong>of</strong> solar cells.<br />

Today, their paths have crossed again in a<br />

research collaboration which they hope will<br />

increase solar-energy uptake by producing<br />

cheaper and more efficient solar cells.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu explains that although thinfilm<br />

technology uses 100 times less silicon<br />

than conventional cells, thereby reducing the<br />

cost <strong>of</strong> photovoltaic solar panels, the cells’<br />

poor absorption <strong>of</strong> near infrared light limits<br />

their performance.<br />

And light performance is <strong>of</strong> particular<br />

interest to Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu. At the Centre for<br />

Micro-Photonics, he and his colleagues study<br />

the process <strong>of</strong> converting light to energy and

June 2009 swinburne<br />

how to make that process more efficient.<br />

A major focus <strong>of</strong> his research is the study<br />

<strong>of</strong> photonic crystals – tiny structures that<br />

can manipulate and control light by multiple<br />

reflection. Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu came up with the<br />

idea <strong>of</strong> developing these photonic crystals to<br />

act as solar cells – to convert light to energy<br />

– and suggested it to Dr Shi.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu says the new solar cells use a<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> photonic crystals treated with<br />

metallic nanoparticles, together with thin-film<br />

photovoltaic technology. The combination<br />

should enable the efficient collection <strong>of</strong> solar<br />

energy in a wider colour range, making the<br />

cells twice as efficient and significantly less<br />

costly to make than other cells.<br />

The new solar cells use nanoparticles to<br />

trap light into a thin-film photovoltaic cell.<br />

“Basically, if you can slow down the light<br />

it will stay in the solar cell longer and thus<br />

convert more light to electricity,” Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Gu says. “If you are able to trap the light<br />

in the part <strong>of</strong> the solar cell where the<br />

conversion is taking place, it becomes even<br />

more efficient.”<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu and his colleagues have<br />

already started work on a model cell, which<br />

will be produced on a pilot scale at Suntech<br />

in China.<br />

“By working with Suntech in the<br />

development phase, we can ensure the<br />

technology can be transferred to the<br />

production line,” he says.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> signed the agreement<br />

with Suntech Power in April and each<br />

organisation will contribute $3 million.<br />

The project is also seeking funding from the<br />

Victorian Government.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu believes the group’s<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> research and business<br />

expertise will allow it to develop and<br />

manufacture the revolutionary solar cells<br />

within five years.<br />

Although he has been approached by<br />

other institutes to pursue similar research,<br />

Dr Shi says he selected the <strong>Swinburne</strong> team<br />

because <strong>of</strong> its expertise in nanotechnology,<br />

which he believes will play an important role<br />

in next-generation solar technology.<br />

For solar power to succeed as a<br />

replacement for existing methods <strong>of</strong><br />

generating electricity, it must be able to<br />

compete with fossil fuel technologies in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> cost and performance and Dr Shi<br />

believes that the new technology could lead<br />

to solar power becoming as cheap as energy<br />

derived from fossil fuels.<br />

And, although Australian demand for<br />

Nanophotonics Down Under 2009<br />

A meeting will be held in Melbourne in June to discuss the emerging field<br />

<strong>of</strong> nanophotonics, which is becoming increasingly important in photonics<br />

applications such as solar energy, information technology, biomedicine and<br />

consumer electronics.<br />

Nanophotonics Down Under 2009 Devices and Applications (SMONP 2009)<br />

will bring together international specialists from industry and academia<br />

to identify key challenges in the emerging applications <strong>of</strong> nanophotonics.<br />

The event will also provide a forum for scientists, engineers and industry<br />

representatives to develop new strategic alliances and partnerships.<br />

The program includes a public lecture on Sunday 21 June to increase<br />

public awareness <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong> nanophotonics in future technological<br />

applications. The lecture, by Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Martin Green from the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

New South Wales, will focus on solar energy.<br />

More information<br />

• Nanophotonics Down Under 2009 Devices and Applications, 21-24 June, Melbourne<br />

Convention and Exhibition Centre, www.smonp2009.com<br />

solar power accounts for less than 1 per cent<br />

<strong>of</strong> the total world market, he says there are<br />

many positive indications for the future <strong>of</strong><br />

the industry in Australia, such as the growing<br />

interest and public support for renewable<br />

energy solutions.<br />

The collaborative research group will<br />

eventually be housed in <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s new<br />

Advanced <strong>Technology</strong> Centre, a $130 million<br />

development due for completion in<br />

early 2011.<br />

Dr Shi is a guest speaker at this year’s<br />

Nanophotonics Down Under conference. ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 MY SWIN (1300 697 946)<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Solar Power<br />

11<br />

IMAGINE<br />

WITH ACCOUNTANTS.<br />

How can calculators and balance sheets be used to combat crime?<br />

Accounting Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Suresh Cuganesan is a leading researcher in performance<br />

measurement who is helping Victoria Police and the Australian Crime Commission<br />

combat organised crime. Read all about it in <strong>Swinburne</strong> Magazine back issues,<br />

available when you subscribe online at www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

For more fascinating <strong>Swinburne</strong> discoveries, subscribe online for free.<br />

QUESTION EVERYTHING<br />

1300 MY SWIN<br />

swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

CRICOS Provider: 00111D

swinburne June 2009<br />

‘green’ business<br />

12<br />

Companies find<br />

a competitive<br />

green<br />

edge<br />

A business environmental mentoring program<br />

is showing that ‘going green’ can win customers<br />

and pr<strong>of</strong>its By Robin Taylor<br />

David Van Berkel <strong>of</strong><br />

Garden Express.<br />

Yarra Valley nurseryman David Van<br />

Berkel was annoyed that people passing<br />

his stand at garden shows would take his<br />

company brochures but leave behind his<br />

plastic showbag. So he came up with an<br />

innovative solution – he asked his supplier to<br />

put a perforated strip across the bottom <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bag, which customers could tear <strong>of</strong>f to turn<br />

the bag into a tree guard. People now happily<br />

accept the plastic carrier. It’s useful to them<br />

and becomes a marketing tool for the nursery.<br />

It’s a subtle piece <strong>of</strong> creative thinking,<br />

which Mr Van Berkel attributes to his<br />

participation in the Business Transformer<br />

Program, run by the National Centre for<br />

Sustainability at <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong>.<br />

He is one <strong>of</strong> a growing number <strong>of</strong><br />

business owners and operators who<br />

have completed the centre’s program<br />

set up to help companies develop more<br />

environmentally sustainable practices.<br />

Mr Van Berkel participated in a 12-month<br />

program run in collaboration with the Shire<br />

<strong>of</strong> Yarra Ranges (see accompanying story).<br />

The centre’s team leader for business and<br />

community sustainability, Scott McKenry,<br />

says the program is designed to encourage<br />

business owners to think differently about<br />

their products and services; how they are<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered, and how they can be future-pro<strong>of</strong>ed<br />

through sustainable growth strategies.<br />

photo: paul Jones

June 2009 swinburne<br />

“We take businesses out <strong>of</strong> their operational<br />

headspace,” he says.<br />

While the centre’s core business is<br />

education, it also develops and delivers<br />

community and business programs in<br />

collaboration with industry, local councils<br />

and communities, which is how the Business<br />

Transformer Program started. The program,<br />

which began in 2006, was originally funded<br />

by Sustainability Victoria and the Victorian<br />

Environment Protection Authority.<br />

In its first year a number <strong>of</strong> large<br />

organisations such as Pilkington Glass (now<br />

Viridian), Huntsman Chemicals and the City<br />

<strong>of</strong> Melbourne participated in the program.<br />

Mr McKenry says a notable outcome <strong>of</strong> that<br />

first program was that Pilkington Glass was<br />

able to secure multi-million-dollar funding<br />

from Sustainability Victoria to build a new<br />

manufacturing facility to make ‘comfort<br />

glass’, which is used in buildings to achieve<br />

a five-star energy rating.<br />

The Business Transformer Program<br />

operates with local councils within a particular<br />

geographical area to encourage businesses to<br />

work together. Twelve businesses participated<br />

in the Yarra Ranges program.<br />

Mr McKenry says the council identified<br />

businesses that were looking for support to<br />

minimise natural resource use, reduce waste<br />

and greenhouse gas emissions, and engage<br />

more effectively, from an environmental<br />

and commercial perspective, with their local<br />

communities.<br />

The Yarra Ranges businesses, which<br />

ranged from a winery to a company<br />

producing cable and antenna systems, showed<br />

that improved environmental performance can<br />

clearly be good business. Over the program’s<br />

12 months the businesses recorded average<br />

cuts in energy consumption <strong>of</strong> 8 to 10<br />

per cent. This represented a $100,000 saving<br />

in energy bills and a reduction <strong>of</strong> about<br />

1800 tonnes in carbon dioxide emissions.<br />

This result was achieved by each business<br />

running (with the centre’s help) its own<br />

project – for example, working with its<br />

supply chain to reduce packaging, improve<br />

efficiency or implementing a behaviourchange<br />

program for customers or staff.<br />

The program includes seminars covering<br />

people’s own business case for sustainability<br />

and stakeholder engagement and these<br />

are supplemented by in-house workshops<br />

on themes like behaviour change, carbon<br />

management, energy efficiency, water<br />

efficiency and project planning.<br />

Advisers from the centre also visit<br />

businesses to help build some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

benchmarks for measuring progress in areas<br />

such as energy and water use and waste.<br />

The Business Transformer Program<br />

stays abreast <strong>of</strong> international trends and<br />

developments through the participation <strong>of</strong><br />

a Canadian business sustainability expert,<br />

Dr Bob Willard.<br />

Dr Willard says the program’s<br />

distinguishing characteristic is the<br />

opportunity it gives participants to apply<br />

what they learn to a real initiative in their<br />

organisation. “Because the program takes a<br />

year to complete, they have a chance to roll<br />

up their sleeves, apply their knowledge, and<br />

learn from their successes and challenges<br />

and those <strong>of</strong> other participants,” he says.<br />

“This helps people become more effective<br />

leaders <strong>of</strong> subsequent projects.”<br />

From his international perspective,<br />

Dr Willard says Australian businesses tend to<br />

work more cooperatively with government<br />

on sustainability issues than businesses in<br />

other countries. “I also sense that Australian<br />

business leaders are more open to good ideas<br />

from elsewhere and are not as inhibited by<br />

the NIH (‘not invented here’) factor. That’s<br />

refreshing.”<br />

In 2008 businesses in the City <strong>of</strong><br />

Casey took part in a shorter version <strong>of</strong> the<br />

transformer program, and in 2009 the City <strong>of</strong><br />

Knox (both are Melbourne municipalities) is<br />

also partnering a program for businesses in<br />

its area.<br />

Mr McKenry says the program is modular<br />

and can be set up and run as required for a<br />

particular council. In response to industry<br />

input, the program now includes more<br />

content on issues related to climate change<br />

and carbon accounting.<br />

Businesses pay a fee, on a sliding scale<br />

according to their size, to participate. The<br />

cost ranges from $1500 for companies with<br />

fewer than 100 employees, to $3000 for<br />

businesses with 100 to 300 employees, and a<br />

negotiable rate for larger companies.<br />

Mr McKenry says that while the programs<br />

to date have all been run by <strong>Swinburne</strong> in<br />

Victoria, there is potential to run them in<br />

other states through the centre’s collaborative<br />

network. ••<br />

The National Centre for Sustainability<br />

is a collaboration <strong>of</strong> several institutions<br />

across Australia: <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong> (Victoria), Sunraysia Institute<br />

<strong>of</strong> TAFE (Victoria), <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ballarat<br />

(Victoria), South West Institute <strong>of</strong> TAFE<br />

(Victoria), Challenger TAFE (Western<br />

Australia) and Tropical North Queensland<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> TAFE.<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 MY SWIN (1300 697 946)<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Case study<br />

Business blooms from<br />

an unexpected marketing edge<br />

For Garden Express owner David Van Berkel, being involved in the Business<br />

Transformer Program provided a fresh perspective on opportunities,<br />

which he says he would otherwise not have thought <strong>of</strong>, for marketing his<br />

company’s green credentials.<br />

Garden Express is a mail order and online garden centre. It publishes a<br />

catalogue five times a year and also produces wholesale flower bulbs for<br />

the nursery industry.<br />

Mr Van Berkel says he started the course just focused on recycling and<br />

energy savings and only as the course progressed did he realise that these<br />

could also create marketing opportunities.<br />

“I became aware that we needed to produce a more environmentally<br />

friendly package and market that to our customers,” he says. “The best<br />

thing for me was to use the power <strong>of</strong> my catalogues and database to tell<br />

my customers what we were doing to become green.”<br />

He says the quickest and easiest change the company made was<br />

reducing energy use in the workplace. Simply by educating staff about<br />

the potential savings to be gained by turning <strong>of</strong>f unused equipment, the<br />

company was able to reduce energy consumption by about 10 per cent, at<br />

no cost, and Mr Van Berkel regards that as just the start.<br />

He said the program showed people how these sorts <strong>of</strong> changes could<br />

improve their business, and even if the change did not result directly in<br />

additional pr<strong>of</strong>it it created a stronger relationship with customers through<br />

being seen to be “doing the right thing”.<br />

He says another gain from the program was the network it created with<br />

other businesses in the shire: “A cable production company is completely<br />

different to a flower bulb company but, at the end <strong>of</strong> the day, if you run a<br />

machine you are in the same business <strong>of</strong> using resources.”<br />

Carbon accountants queue<br />

for accreditation<br />

In keeping with the political momentum building behind a national carbon<br />

trading scheme, <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s National Centre for Sustainability has<br />

been inundated with demand for its course in carbon accounting. Since<br />

introducing the course (Australia’s first accredited carbon accounting course)<br />

in May 2008, a steady stream <strong>of</strong> budding carbon accountants have signed up<br />

to become accredited.<br />

A significant part <strong>of</strong> the centre’s work in the past few years has been<br />

developing greenhouse gas management strategies for businesses. Scott<br />

McKenry says this work <strong>of</strong>ten involves partnering with the country’s<br />

foremost experts in the field, who now act as course facilitators.<br />

“We haven’t even marketed the course and every intake has been full,”<br />

he says.<br />

Last year, eight groups <strong>of</strong> 16 participants completed the course and this<br />

year another 14 groups <strong>of</strong> 16 are scheduled to take part.<br />

“There are a lot <strong>of</strong> consultants who want accreditation, as well as<br />

people from emissions-intensive industries and local councils, many <strong>of</strong><br />

which will have potential liabilities under an emissions trading scheme,”<br />

Mr McKenry says.<br />

The hands-on course requires participants to carry out carbon<br />

accounting in their workplace and provide evidence to show they can<br />

develop an emissions inventory and report.<br />

More information<br />

• www.swinburne.edu.au/ncs/Education/CarbonAcc.html<br />

‘green’ business<br />

13

swinburne JUne 2009<br />

Maren Rawlings<br />

workplace<br />

14<br />

No joke when it’s<br />

survival <strong>of</strong><br />

the funniest<br />

story by Bianca Nogrady & Rebecca Thyer<br />

In uncertain economic times when many<br />

people are worried about keeping their jobs,<br />

it’s understandable that some workplaces<br />

may be losing the jocular banter that<br />

otherwise relieves the working day.<br />

But this doesn’t mean that humour has left<br />

the <strong>of</strong>fice. Quite the contrary, it seems, with<br />

humour acquiring a competitive edge as it<br />

becomes part <strong>of</strong> some people’s survival strategy.<br />

Qualitative evidence uncovered by<br />

,,<br />

When stress<br />

levels increase<br />

people tend<br />

to use their<br />

humour<br />

competitively.”<br />

Maren Rawlings<br />

photo: paul Jones<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> PhD researcher Maren Rawlings<br />

suggests that some types <strong>of</strong> humour – the<br />

type that targets particular people as the butt<br />

<strong>of</strong> jokes – regularly occurs in the workplace.<br />

And this type <strong>of</strong> humour could be on the rise.<br />

Ms Rawlings, a psychologist in<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Faculty <strong>of</strong> Life and Social<br />

Sciences and a former teacher, says that the<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> competitive humour clearly increases<br />

as work environments become more stressed.<br />

“People are very generous to each other<br />

when things are going well, but that starts<br />

to change when workplaces become tense.<br />

People start to compete and humour becomes<br />

strategic.”<br />

Although it might seem a trivial<br />

consequence <strong>of</strong> a downturn in global fortunes,<br />

this sort <strong>of</strong> humour has wider implications.<br />

Ms Rawlings’s research is finding,<br />

unsurprisingly, that ‘bad humour’ can reduce<br />

people’s job satisfaction and their perception<br />

<strong>of</strong> their own and others’ productivity.<br />

Ms Rawlings has measured the impact<br />

on organisations <strong>of</strong> how humour is used at<br />

work. This has led to her development <strong>of</strong> a<br />

tool that assesses workplace humour.<br />

Called the Humour at Work scale (HAW)<br />

it is a proxy measure <strong>of</strong> the atmosphere <strong>of</strong><br />

a workplace and it predicts employees’ job<br />

satisfaction. She has found that it can explain<br />

variations in productivity between <strong>of</strong>fices or<br />

worksites.<br />

The HAW scale is likely to be<br />

commercialised later this year for use by<br />