March 2010 - Swinburne University of Technology

March 2010 - Swinburne University of Technology

March 2010 - Swinburne University of Technology

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

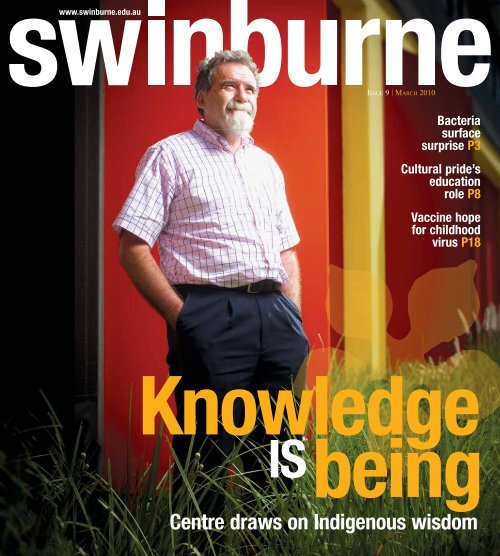

www.swinburne.edu.au<br />

Issue 9 | <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

Bacteria<br />

surface<br />

surprise P3<br />

Cultural pride’s<br />

education<br />

role P8<br />

Vaccine hope<br />

for childhood<br />

virus P18<br />

Knowledge<br />

isbeing<br />

Centre draws on Indigenous wisdom

www.swinburne.edu.au<br />

ISSUE 9 | MARCH <strong>2010</strong><br />

swinburne <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

Contents<br />

Issue 9 | <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

Bacteria<br />

surface<br />

surprise P3<br />

Cultural pride’s<br />

education<br />

role P8<br />

Vaccine hope<br />

for childhood<br />

virus P18<br />

08<br />

14<br />

Knowledge<br />

being<br />

IS<br />

Centre draws on Indigenous wisdom<br />

Swin_1003_p01.indd 1 26/02/10 3:48 PM<br />

Upfront<br />

2<br />

social inclusion bridging the gap<br />

Australia is home to the world’s oldest living culture. Our Indigenous<br />

culture and history is one <strong>of</strong> our most precious cultural assets.<br />

However, the Australian community’s knowledge <strong>of</strong> its Indigenous<br />

background is scant; the depth <strong>of</strong> tradition and history unique to this<br />

country, barely scratched. This wide gulf in awareness and understanding<br />

is one <strong>of</strong> the reasons why most non-Indigenous Australians remain<br />

unaware <strong>of</strong> the enormous challenges that so many Indigenous Australians<br />

face on a daily basis.<br />

The representations <strong>of</strong> Indigenous Australians in our mainstream media<br />

continues to perpetuate the false perception that ‘real’ Indigenous culture<br />

exists only in remote Australia. The reality is that everyone in this land is<br />

standing on what was once Indigenous land. Indigenous Australian history<br />

is all around us – not just in the Red Centre and Top End … the Kimberley,<br />

Arnhem Land and Uluru. It is in our CBDs, along the corridors <strong>of</strong> urban sprawl,<br />

and woven intrinsically through the mountains and coastlines that backdrop<br />

our lives in our towns and cities.<br />

For most Australians the ripple effects <strong>of</strong> the colonial era and ethos have<br />

been left behind in history, but they have been felt every day for more<br />

than 220 years by Indigenous Australians. An understanding <strong>of</strong> this and<br />

how it still affects people’s lives is critical to bridging the cultural gap that<br />

exists between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia.<br />

Our increasingly multicultural society has placed even greater pressures<br />

on the need to understand and alleviate the continuing effects <strong>of</strong> the<br />

attitudes, beliefs and legalism entrenched by our colonial origins. Prime<br />

Minister Rudd’s 2008 apology (on behalf <strong>of</strong> the Australian Government)<br />

articulated how important this is.<br />

Education, clearly, has a major role and responsibility. <strong>Swinburne</strong> is taking<br />

important steps to bridge this gap in understanding. Through programs and<br />

innovations at both higher education and TAFE level (some <strong>of</strong> which are<br />

outlined in this issue), the university is proactively linking contemporary<br />

Australia, education, Indigenous culture and community development.<br />

Utilising <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s geographical location on traditional Wurundjeri<br />

land and our cross-sector, multi-campus advantage, these programs<br />

are reaching out to Indigenous communities and gradually to the wider<br />

Australian community.<br />

It is a new, creative approach that is broadening the delivery and lengthening<br />

the reach <strong>of</strong> education. Critically, it is strengthening Indigenous education –<br />

allowing ‘the bridge’ to be built from both sides <strong>of</strong> the cultural divide.<br />

Andrew Peters<br />

Wurundjeri / Yorta Yorta descendant,<br />

Lecturer, Indigenous Studies and Tourism, <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

cover story<br />

06 Centre to<br />

tap knowledge<br />

as a way <strong>of</strong> being<br />

A new centre for Indigenous<br />

knowledge and design<br />

anthropology is set to shape<br />

the way knowledge is shared<br />

in Western universities<br />

<br />

Features<br />

Karin Derkley<br />

03 ‘Clingy’ bacteria<br />

surprise comes to<br />

the surface<br />

<br />

Diny slamet<br />

04 video on the moment<br />

our immune system<br />

fails<br />

Sometimes the human<br />

immune system fails, betrayed<br />

by its own defenders.<br />

Scientists have found a<br />

way to witness this ‘cellular<br />

warfare’ to, hopefully, identify<br />

what goes wrong<br />

<br />

Graeme O’Neill<br />

08 cultural pride<br />

helps education<br />

start making sense<br />

A <strong>Swinburne</strong> TAFE program<br />

run in partnership with<br />

Victorian Aboriginal<br />

organisations is creating some<br />

stability for disadvantaged<br />

Indigenous youths<br />

<br />

karin derkley<br />

10 colourful, creative<br />

and fighting to stay<br />

local<br />

Indigenous community<br />

television plays an important<br />

role in remote communities,<br />

but faces an uncertain future<br />

with Australia’s imminent<br />

conversion to digital television<br />

<br />

Karin Derkley<br />

12 the ultimate wave<br />

By observing pulsars,<br />

researchers hope to discover<br />

space’s most elusive waves<br />

and thus gain new insights<br />

into the universe<br />

<br />

julian cribb<br />

14 An Australian tissue<br />

engineer in paris<br />

dr gio Braidotti<br />

16 human antennae<br />

tuned t0 the future<br />

The future can both excite and<br />

terrify. Helping people master<br />

this forward journey is the role<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘strategic foresight’<br />

dr gio Braidotti<br />

18 Synthetic vaccine<br />

hope in fight against<br />

polio successor<br />

Researchers are working on<br />

synthetic vaccines, which<br />

are potentially safer, cheaper<br />

and more practical than<br />

conventional biological vaccines<br />

<br />

Julian cribb<br />

20 Continuous system<br />

check could release<br />

data-processing<br />

‘brake’<br />

<br />

david adams<br />

21 i phone, i shop …<br />

nutrition at your<br />

fingertips<br />

<br />

tim treadgold<br />

22 greyfields revisited<br />

Australian cities’ ageing<br />

residential tracts – ‘greyfields’<br />

– <strong>of</strong>fer environmental and<br />

economic solutions to<br />

Australia’s hunger for city<br />

housing<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Peter Newton<br />

•• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• ••<br />

18<br />

21<br />

Published by <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

Editor: Dorothy Albrecht, Director, Marketing Services<br />

Deputy editor: Julianne Camerotto, Communications Manager<br />

(Research and Industry), Marketing Services,<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>, Melbourne<br />

The information in this publication was correct at the time <strong>of</strong> going to press, <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong>.<br />

The views expressed by contributors in this publication are not necessarily those <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>.<br />

Written, edited, designed and produced on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong> by Coretext, www.coretext.com.au, +61 3 9670 1168<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

John Street (PO Box 218), Hawthorn, Victoria, 3122, Australia<br />

Enquiries: +61 3 9214 8000<br />

Website: www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Email: magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

eSubscribe to <strong>Swinburne</strong> magazine: www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine/subscribe<br />

CRICOS provider Code 00111D<br />

ISSN 1835-6516 (Print) ISSN 1835-6524 (Online)<br />

Cover photo: Paul Jones

march <strong>2010</strong> swinburne<br />

‘Clingy’ bacteria surprise<br />

comes to the surface<br />

story by Diny Slamet<br />

Improving the success rate <strong>of</strong> artificial<br />

implants. Reducing the risk <strong>of</strong> dangerous<br />

Staphylococcus outbreaks in hospitals.<br />

Dramatically reducing the amount <strong>of</strong> fuel<br />

oil burned by the world’s merchant shipping<br />

fleet. It is a disparate list, but nonetheless it<br />

is the set <strong>of</strong> research goals that a <strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> research team has<br />

begun to pursue.<br />

The issues all stem from bacterial activity,<br />

in particular the way bacteria adhere to<br />

surfaces by creating a ‘bi<strong>of</strong>ilm’ that protects<br />

the bacteria from the usual sterilisation<br />

treatments.<br />

The <strong>Swinburne</strong> team, working with<br />

specialists from Monash <strong>University</strong>,<br />

combines the skills <strong>of</strong> scientists <strong>of</strong><br />

different specialisations – microbiology,<br />

nanotechnology, engineering and industrial<br />

sciences – to seek remedies that cannot be<br />

achieved by one discipline alone.<br />

The team is led by microbiologist<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Elena Ivanova and includes<br />

surface chemist Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Russell Crawford<br />

– who is also Dean <strong>of</strong> <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Life and Social Sciences – and<br />

physical metallurgists Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Yuri Estrin<br />

and Dr Rimma Lapavok from Monash<br />

<strong>University</strong>.<br />

The problems caused by bacteria cost<br />

industries such as healthcare, hospitality<br />

and shipping billions <strong>of</strong> dollars each year.<br />

The rewards to individuals and society for<br />

solving the more intractable problems, such<br />

as hospital-borne infections, are immense.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most troublesome issues <strong>of</strong><br />

modern medicine is infection-related implant<br />

failures. According to Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ivanova,<br />

up to 67 per cent <strong>of</strong> implants are troubled<br />

by bacterial problems. Despite thorough<br />

sterilisation processes, this high percentage <strong>of</strong><br />

medical implants (commonly hips and knees)<br />

fail because some types <strong>of</strong> bacteria attach to<br />

the implant as a bi<strong>of</strong>ilm, from which they<br />

cause further infection. The only solution is<br />

to remove the infected implant and replace it.<br />

The research team has already made great<br />

strides by disproving a common hypothesis<br />

that had previously led researchers down a<br />

blind alley. While not a great deal is known<br />

about the forces that attract bacteria to<br />

solid surfaces, the common hypothesis was<br />

that bacteria attach more easily to rougher<br />

surfaces because the microscopic valleys on<br />

that surface provide shelter from commonly<br />

used disinfection processes. Some implant<br />

manufacturers are even going down the road<br />

<strong>of</strong> making their products ‘nano-smooth’ so<br />

the bacteria cannot find protection from<br />

sterilisation processes.<br />

But the scientists have made a surprising<br />

discovery. Working with nano-smooth<br />

titanium and a range <strong>of</strong> microbiological<br />

analysis techniques, the researchers have<br />

found that rather than making it harder for<br />

bacteria to adhere to, smooth surfaces seem<br />

to be more attractive to some problematic<br />

bacteria, with a higher degree <strong>of</strong> bacterial<br />

colonisation on smooth surfaces than on<br />

rough.<br />

“The way bacteria attach to nanosmooth<br />

surfaces is different to the way<br />

they adhere to rough surfaces,” explains<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Crawford. “The bacteria adhere to<br />

these surfaces by secreting an extracellular<br />

polymeric substance (EPS), which is a<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> sugars and proteins. This<br />

is the first time it has been shown that the<br />

EPS is produced in much greater quantities<br />

when bacteria come into contact with nanosmooth<br />

surfaces, causing a greater amount <strong>of</strong><br />

bacterial attachment.”<br />

The research suggests that hospitals may<br />

have to rethink their disinfection techniques<br />

and that manufacturers may have to develop<br />

new disinfectants.<br />

“Many bacterial disinfectants used today<br />

are based on positively charged (or cationic)<br />

surfactants. These attach to the negatively<br />

charged bacteria, causing their cell wall<br />

to rupture and killing the bacteria. This<br />

new research has highlighted the need for<br />

disinfectant manufacturers to formulate new<br />

products that attack both the EPS and the<br />

bacterial cells, and not just the bacterial cells<br />

alone,” Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Crawford says.<br />

Shipping is another industry where the<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> research may contribute to a big<br />

increase in efficiency. Scientists estimate that<br />

a bi<strong>of</strong>ilm (or bacterial build-up) the thickness<br />

<strong>of</strong> just a human hair on a ship’s hull can<br />

add US$400 an hour to fuel costs because it<br />

affects the ship’s drag, causing greater fuel<br />

consumption.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the techniques used to limit the<br />

build-up <strong>of</strong> bi<strong>of</strong>ilm on ships’ hulls work for<br />

Photo: iStockphoto / Malcolm Fife<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> research will help to develop surface<br />

coatings that reduce the ability <strong>of</strong> bacteria to<br />

build a film on ships’ hulls. This could save<br />

the global shipping industry millions <strong>of</strong> tonnes<br />

<strong>of</strong> oil a year because the ships will be able to<br />

move through the water more easily.<br />

a limited time and have a severe ecological<br />

downside, with toxic chemicals being used<br />

in most marine paints.<br />

The <strong>Swinburne</strong> research is adding to<br />

the body <strong>of</strong> knowledge that will lead to the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> surface coatings that can<br />

reduce the ability <strong>of</strong> bacteria to build a film<br />

on ships’ hulls. This could save the global<br />

shipping industry millions <strong>of</strong> tonnes <strong>of</strong> oil a<br />

year because the ships will be able to move<br />

through the water more easily.<br />

The work <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Swinburne</strong> scientists<br />

is still at the early research stage. “We are<br />

really looking at what causes bi<strong>of</strong>ilms to<br />

form and how well they form on a range<br />

<strong>of</strong> different surfaces. Once we publish<br />

our results we hope they will be used<br />

by companies to produce more effective<br />

disinfection processes and surface coatings,”<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Crawford says. ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 275 788<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Key points<br />

The way bacteria adhere<br />

to surfaces – by creating a<br />

‘bi<strong>of</strong>ilm’ that protects them<br />

from the usual sterilisation<br />

treatments – is being<br />

investigated<br />

The <strong>Swinburne</strong> research<br />

team, working with<br />

specialists from Monash<br />

<strong>University</strong>, combines<br />

skills in microbiology,<br />

nanotechnology,<br />

engineering and industrial<br />

sciences<br />

The work could improve<br />

the success rate <strong>of</strong> artificial<br />

implants, reduce the risk <strong>of</strong><br />

Staphylococcus outbreaks<br />

in hospitals and reduce the<br />

fuel consumption <strong>of</strong> ships<br />

surface science<br />

3

swinburne <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

Dr Sarah Russell, immunologist at Peter MacCallum<br />

Cancer Centre and <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong>, is working with physicists to develop<br />

new imaging tools to study T-cells in vitro.<br />

human health<br />

4<br />

The body is a microbiological battlefield on which our immune system fights to keep us well.<br />

Sometimes it fails, betrayed by its own defenders. Scientists have now found a way to actually witness<br />

this cellular warfare and hopefully identify what goes wrong By Graeme O’Neill<br />

Photo: Paul Jones<br />

As we live and breathe, millions <strong>of</strong> T-cells<br />

that are part <strong>of</strong> the human body’s molecular<br />

defence force patrol the blood and lymphatic<br />

systems, seeking out and destroying cells<br />

harbouring viruses and bacteria or mutant<br />

cells that could turn cancerous.<br />

T-cells are assassins and fortunately, in<br />

the main, they are on our side. The trouble<br />

is, these immune-system bodyguards can<br />

also turn treacherous.<br />

In some individuals they attack healthy<br />

tissue, causing autoimmune disorders such<br />

as rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes,<br />

multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus<br />

erythematosus.<br />

To try to find out why, immunologist<br />

Dr Sarah Russell, <strong>of</strong> Melbourne’s Peter<br />

MacCallum Cancer Centre and <strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>, has teamed up<br />

with Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Min Gu’s research group at<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Centre for Microphotonics to<br />

develop new imaging tools to study T-cells in<br />

vitro.<br />

Dr Russell – the recent recipient <strong>of</strong> a<br />

prestigious Australian Research Council Future<br />

Fellowship – and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu are hoping this<br />

close-up exploration <strong>of</strong> the T-cells’ structure,<br />

as they develop their specialised forms and<br />

functions, will provide clues to what goes<br />

wrong and triggers an autoimmune disease.<br />

Key points<br />

In autoimmune diseases,<br />

the ‘assassins’ <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human immune system,<br />

T-cells, for some reason<br />

turn on and attack healthy<br />

tissue<br />

Using a video camera<br />

linked to a microscope,<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Dr Sarah<br />

Russell will be able to<br />

observe the development <strong>of</strong><br />

T-cells at close range and<br />

try to establish what goes<br />

wrong<br />

The research will also use<br />

PALM (photo-activated<br />

luminescence microscopy),<br />

which allows observation<br />

<strong>of</strong> individual cells and even<br />

individual proteins<br />

It is a complex and fascinating process at<br />

the heart <strong>of</strong> human biology.<br />

As part <strong>of</strong> the project, the researchers are<br />

creating a biochip to study the development<br />

and behaviour <strong>of</strong> T-cells, individually<br />

corralled within microscopic ‘paddocks’<br />

formed by a microgrid <strong>of</strong> silane polymer<br />

‘fences’ deposited on silicon.<br />

“The biochip will allow us to cage<br />

single cells as we observe their individual<br />

development, instead <strong>of</strong> trying to monitor<br />

20-plus cells at a time,” Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu says.<br />

The window to this extraordinary<br />

research is a video camera linked to a laser<br />

confocal microscope. This will deliver highresolution,<br />

dynamic images <strong>of</strong> the confined<br />

cells responding to biochemical signals piped<br />

into the ‘paddocks’ through a network <strong>of</strong><br />

micr<strong>of</strong>luidic channels etched into the chip’s<br />

surface.<br />

Dr Russell says the apparatus will provide<br />

the first real-time video images that monitor<br />

T-cells over multiple generations, with<br />

precursor cells moving, changing shape,<br />

dividing and differentiating into mature<br />

T-cells with specialised forms and functions.<br />

“T-cells form from bone marrow stem<br />

cells that migrate to the thymus, where they<br />

undergo a complex process <strong>of</strong> differentiation<br />

and selection,” she explains.<br />

The thymus gland, high in the chest, is<br />

‘T-cell university’, where cells progressively<br />

differentiate into naïve, functionally specialised<br />

T-cells (‘naïve’ because they have yet to be<br />

activated by exposure to alien antigens).<br />

As they ‘graduate’ they are ready to<br />

be activated in the event <strong>of</strong> an external<br />

or internal threat. Once activated, mature<br />

T-cells undergo final transformation into:<br />

effector T-cells – programmed to kill any<br />

cells advertising their infected or precancerous<br />

state by displaying unfamiliar,<br />

‘non-self’ protein antigens on their<br />

surface; or<br />

memory T-cells, that can linger in the body<br />

for decades, ready to reactivate and rapidly<br />

repopulate the body with new effector<br />

T-cells should they detect the familiar<br />

antigenic signature <strong>of</strong> an old enemy.<br />

Dr Russell and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Gu expect<br />

the biochip will allow them to observe<br />

and record the complex process <strong>of</strong> T-cell<br />

development, maturation and activation<br />

in vitro, and in unprecedented detail.<br />

In addition to conventional laser confocal<br />

microscopy, they will use a powerful new<br />

technique called photo-activated luminescence<br />

microscopy (PALM), capable <strong>of</strong> resolving<br />

individual cells in nanoscale detail. PALM<br />

can even track individual protein molecules.

<strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong> swinburne<br />

It works by attaching DNA sequences<br />

for luminescent protein ‘tags’ to genes for<br />

native cellular proteins. These ‘tags’ cause<br />

the hybrid proteins to glow green or cherry<br />

red under laser light, allowing researchers to<br />

observe their movement and interactions.<br />

Dr Russell’s <strong>Swinburne</strong> research focuses<br />

on a suite <strong>of</strong> polarity proteins that have been<br />

conserved across the billion-year evolutionary<br />

divide between simple nematode worms and<br />

humans.<br />

Polarity proteins play integral roles in<br />

almost every aspect <strong>of</strong> a T-cell’s life cycle and<br />

function and are a key focus <strong>of</strong> the research.<br />

In three-dimensional space, polarity<br />

proteins aggregate at one ‘end’ <strong>of</strong> the cell,<br />

providing an internal reference point that<br />

allows the cell to orient and link to its<br />

neighbours to form the highly organised,<br />

layered structures <strong>of</strong> bone, cartilage, s<strong>of</strong>t<br />

tissues and organs.<br />

T-cells are motile and fluid in form and<br />

investigations by Dr Russell and other<br />

international investigators have shown that<br />

the same suite <strong>of</strong> polarity proteins found in<br />

static cells is involved in nearly every aspect<br />

<strong>of</strong> T-cell development and function.<br />

Dr Russell explains that polarity proteins<br />

underpin T-cells’ ability to move, to<br />

orientate towards biochemical cues in their<br />

environment, to change form and function, to<br />

recognise alien protein fragments (antigens)<br />

presented to them by sentry cells, and to<br />

undergo clonal expansion.<br />

She says polarity proteins are believed<br />

to form complexes that manipulate the<br />

cytoskeleton, the internal network <strong>of</strong><br />

microtubules that stabilises and shapes the<br />

cell, and allows it to move and make contact<br />

with other immune-system cells.<br />

From this, and as part <strong>of</strong> the probe into<br />

why T-cells sometimes turn against us,<br />

Dr Russell hopes to detail what happens<br />

within a structure called the immune synapse,<br />

which is involved in activating T-cells to<br />

attack cells displaying unfamiliar antigens.<br />

The immune synapse forms when a naïve<br />

T-cell ‘docks’ with a specialised antigenpresenting<br />

cell that is displaying an alien<br />

antigen in a groove on its surface.<br />

There is still much to be learnt about how<br />

the cells signal each other and come together<br />

to form the synapse, or how the antigen is<br />

subsequently transferred to the T-cell for use<br />

as a template to recognise and destroy infected<br />

or mutant cells.<br />

Dr Russell also wants to investigate<br />

the role <strong>of</strong> polarity proteins in asymmetric<br />

division, a process crucial to T-cell<br />

development, maturation and activation.<br />

In the face <strong>of</strong> threat, the immune system<br />

must create a host <strong>of</strong> new T-cells – and it<br />

creates these from non-specialised precursor<br />

cells, without depleting its reserve <strong>of</strong> precursor<br />

cells. Precursor cells are cells that are incapable<br />

<strong>of</strong> self-renewal and instead differentiate into<br />

one or two closely related final forms.<br />

When precursor cells divide they can<br />

either produce twin clones <strong>of</strong> the original cell<br />

(symmetric division), or a non-identical pair<br />

– a single daughter clone and a cell that has<br />

taken the next step towards differentiating into<br />

an activated T-cell (asymmetric division).<br />

Dr Russell and <strong>Swinburne</strong> researchers are<br />

developing automated systems to capture<br />

and analyse the high-resolution images <strong>of</strong><br />

these processes. “We’ve come a long way in<br />

developing the s<strong>of</strong>tware, and in constructing<br />

microgrids on the biochips,” Dr Russell says.<br />

“But we still have a long way to go to<br />

develop the micr<strong>of</strong>luidic system to manipulate<br />

the biochemical signals to the cells.<br />

“We’ve already obtained some images<br />

without manipulating the signalling<br />

environment process. We’re pretty good<br />

at imaging with standard fluorescence<br />

microscopy, but we have to learn a whole<br />

range <strong>of</strong> new skills to do PALM imaging.”<br />

Dr Russell says much <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

team’s work will depend on being able to<br />

obtain images at the level <strong>of</strong> individual<br />

protein molecules.<br />

By studying T-cells undergoing normal<br />

differentiation in vitro, Dr Russell says<br />

they should be able to identify errors that<br />

unbalance the process, potentially resulting<br />

in lymphoma or leukaemia blood cancers.<br />

“I suspect any defects in polarity and<br />

asymmetric cell division will be apparent long<br />

before any autoimmune problem,” she says.<br />

“Our work is likely to make a difference<br />

to understanding how polarisation develops,<br />

and how it influences each step in T-cell<br />

differentiation and activation.<br />

“For example, when the immune system<br />

has eliminated an infection, most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

T-cells involved die <strong>of</strong>f, leaving just a small<br />

population <strong>of</strong> memory T-cells to keep watch<br />

for any future infections by the same microbe.<br />

“And we hope to define the key processes<br />

that determine whether precursor cells will<br />

differentiate into effector or memory T-cells.”<br />

Dr Russell says that by providing<br />

the first comprehensive picture <strong>of</strong> T-cell<br />

development and maturation, the <strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

project should provide clues to the origins <strong>of</strong><br />

autoimmune disorders and help inform the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> a new generation <strong>of</strong> vaccines<br />

against infection and cancer. ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 275 788<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Fast facts<br />

ILLustrations: Paul Dickenson<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> signs environmental treaty<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong> has signed the Talloires Declaration,<br />

committing itself to raising awareness about the need to move towards<br />

an environmentally sustainable future. Created at a conference in<br />

Talloires, France, in 1990, the declaration aims to demonstrate educational<br />

institutions’ roles as world leaders in developing, promoting and maintaining<br />

global sustainability. <strong>Swinburne</strong> has pledged to engage in education,<br />

research, policy and information exchange to promote an understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

sustainability among staff, students and the community.<br />

Ground control to Melbourne<br />

A newly installed control room at <strong>Swinburne</strong> will allow astronomers in<br />

Melbourne to remotely control<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the world’s largest optical<br />

telescope – 9000 kilometres<br />

away. The facility will see<br />

astronomers controlling the<br />

movements <strong>of</strong> the massive twin<br />

Keck 10-metre Telescopes on the summit <strong>of</strong><br />

Hawaii’s dormant Mauna Kea volcano. This is<br />

the farthest distance from which a telescope <strong>of</strong><br />

this class has been remotely controlled in real time.<br />

Online portal helps children with autism<br />

A series <strong>of</strong> free online computer games designed for children with autism<br />

has been created by a group <strong>of</strong> <strong>Swinburne</strong> multimedia students, the National<br />

eTherapy Centre and Melbourne-based Bulleen<br />

Heights Autism School. WhizKid Games aims to<br />

help autistic children develop independent living<br />

skills, focusing on coping with change, recognising<br />

emotions and non-verbal communication. It includes<br />

16 therapeutic games about everyday activities. See<br />

www.whizkidgames.com.<br />

What’s so good about being a gran?<br />

Researchers from <strong>Swinburne</strong> and the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Melbourne are<br />

still looking for women to tell their stories about their experiences as a<br />

contemporary grandma. Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Susan Moore and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dorothy<br />

Rosenthal plan to write a book and are interested in hearing from all<br />

grandmothers who believe they have something to say about this interesting<br />

and challenging life stage. To access the anonymous survey, visit<br />

www.granresearch.com, or call 1300 275 788 to request a hard copy.<br />

Attitudes to GM foods unchanged<br />

Public attitudes to genetically modified (GM) foods are not changing,<br />

according to findings by <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s National Science and <strong>Technology</strong> Monitor.<br />

Most Australians are still uncomfortable with<br />

GM foods, a constant attitude since 2003. A<br />

thousand people were interviewed in<br />

September 2008 and when asked<br />

how comfortable they were with<br />

GM plants for food, the average score<br />

was 3.9 on a scale <strong>of</strong> 10, with 0 being<br />

‘not at all comfortable’ and 10 being ‘very<br />

comfortable’. The study found a lack <strong>of</strong><br />

trust in the institutions responsible for<br />

commercialising new plant varieties.<br />

5

swinburne <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

social inclusion<br />

knowledge<br />

as a way<br />

<strong>of</strong> being<br />

6<br />

A new centre for Indigenous<br />

knowledge and design<br />

anthropology is set to shape the<br />

way knowledge is shared<br />

in Western universities<br />

By Karin Derkley<br />

How do you work with or for people unless<br />

you understand how they see and experience<br />

the world? How do you create products,<br />

design systems and provide services unless<br />

you have an insight into what is meaningful<br />

or relevant?<br />

For a designer, these are basic questions<br />

if design and function are to meet. The<br />

same questions are also fundamental when<br />

reaching across cultures, particularly when<br />

working with Indigenous communities.<br />

For Dr Norman Sheehan, it makes sense<br />

to bring the two aspirations together and<br />

provide a way for Indigenous knowledge<br />

– <strong>of</strong>ten more holistic than prescriptive – to<br />

influence teaching in Western universities.<br />

To this end, Dr Sheehan has been engaged<br />

by <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong>’s<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Design to establish the Centre<br />

for Indigenous Knowledge and Design<br />

Dr Norman Sheehan

<strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong> swinburne<br />

Key points<br />

Wiradjuri man Dr Norman<br />

Sheehan is to help set up<br />

a new Centre for<br />

Indigenous Knowledge<br />

and Design Anthropology<br />

The new centre aims to<br />

introduce Indigenous<br />

influences to the way<br />

knowledge is taught<br />

and regarded in<br />

Western universities,<br />

with an understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> Indigenous ways <strong>of</strong><br />

knowing and experiencing<br />

the world<br />

Indigenous knowledge<br />

could be integral to the<br />

design <strong>of</strong> products,<br />

services and education<br />

programs<br />

For information on how<br />

you can support social<br />

inclusion initiatives at<br />

,,<br />

Indigenous<br />

knowledge is<br />

a discipline<br />

that focuses<br />

on knowledge<br />

not just as an<br />

accumulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> facts, but<br />

as a way <strong>of</strong><br />

understanding<br />

and living in<br />

the world,<br />

informing<br />

everything<br />

we do.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>, see page 23<br />

Photo: Paul Jones<br />

Anthropology (CIKADA). He will be<br />

assisted by Elizabeth ‘Dori’ Tunstall, who<br />

has recently been appointed as Associate<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Design Anthropology. Formerly<br />

at Chicago’s <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Illinois – one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the top US design schools – Associate<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Tunstall was one <strong>of</strong> the architects<br />

<strong>of</strong> the new US National Design Policy.<br />

Dr Sheehan says <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s decision<br />

to establish the centre is an important step<br />

towards rebalancing the way knowledge is<br />

taught and regarded in Western universities.<br />

“Too much emphasis has been placed on<br />

acquiring and mining knowledge and not<br />

enough on developing an understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge as a way <strong>of</strong> being, or existing.<br />

What we are aiming to do with the centre is<br />

to develop Indigenous knowledge as a basis<br />

for educational programs for everybody.”<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ken Friedman, Dean <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Design, says CIKADA aims to<br />

<strong>of</strong>fer new ways <strong>of</strong> thinking and working<br />

to people interested in design. “In design<br />

we are always looking at how we can use<br />

different knowledge traditions to create<br />

better products, processes and services. Our<br />

aim is to use the laws <strong>of</strong> anthropology to<br />

study how people perceive products and<br />

services and how they will integrate them<br />

into their lives.”<br />

For Dr Sheehan, establishing the centre<br />

represents the culmination <strong>of</strong> a long journey<br />

from a childhood where he was all but cut<br />

<strong>of</strong>f from his Indigenous heritage. A Wiradjuri<br />

man, born in Mudgee, New South Wales,<br />

Dr Sheehan was brought up in a Catholic<br />

boarding school. He says it was not until<br />

he started teaching art within Aboriginal<br />

communities that he became aware <strong>of</strong> the<br />

depth <strong>of</strong> his Aboriginal heritage. “I was<br />

teaching a couple <strong>of</strong> elders in the group, and<br />

they ended up teaching me much more about<br />

my culture than I could ever teach them.”<br />

The knowledge imparted by those elders<br />

has influenced Dr Sheehan’s work ever<br />

since. In his postgraduate work at the Sydney<br />

Art Institute, he produced sculptures that<br />

represented Australian colonial history from<br />

an Aboriginal point <strong>of</strong> view. He has taught in<br />

Aboriginal communities in NSW, Queensland<br />

and Tasmania; recently completed a<br />

postdoctoral fellowship in psychiatry at<br />

the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Queensland’s School <strong>of</strong><br />

Medicine that addressed Aboriginal and<br />

Torres Strait Islander social and emotional<br />

wellbeing; and in 2009 he was the recipient<br />

<strong>of</strong> the South-East Queensland National<br />

Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance<br />

Committee award for his teaching and<br />

scholarship in the Indigenous community.<br />

Over the years Dr Sheehan has been<br />

drawing on his deepening understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> Indigenous culture to develop a body<br />

<strong>of</strong> work around the growing discipline <strong>of</strong><br />

Indigenous knowledge. It is a discipline<br />

that focuses on knowledge not just as an<br />

accumulation <strong>of</strong> facts, but as a way <strong>of</strong><br />

understanding and living in the world,<br />

informing everything we do. “For Indigenous<br />

people this approach to knowledge is<br />

fundamental to everyday life.”<br />

Research and education in Indigenous<br />

communities has <strong>of</strong>ten failed in the past<br />

because it has sought to impose white<br />

values on Aboriginal people rather than<br />

empowering Aboriginal people to research<br />

and educate themselves, he says.<br />

“A lot <strong>of</strong> problems need healing, but only<br />

Aboriginal knowledge can do this. You have<br />

to reinforce a community from within with<br />

programs that include that community’s<br />

voice and values.”<br />

Among the assignments in which<br />

Dr Sheehan has employed that methodology<br />

was an Australian Research Council-funded<br />

project to develop a design-based visual<br />

and oral research method for collecting and<br />

making sense <strong>of</strong> data across different cultural<br />

understandings. The program uses symbols<br />

to track movement in a narrative, allowing<br />

marginalised groups to create images to<br />

represent their community’s journey towards<br />

improved wellbeing.<br />

“Knowing and tracking are fundamental<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> Indigenous knowledge,”<br />

Dr Sheehan says. “If you can track narratives<br />

you can develop deeper understandings <strong>of</strong><br />

the social forces that influence peoples’<br />

lives.” The symbols work as a set <strong>of</strong> tools<br />

that groups can use to build an instigation<br />

model that helps them build their own<br />

pathways to self-understanding and healing.<br />

Dr Sheehan’s work has contributed to ways<br />

<strong>of</strong> exploring issues at the heart <strong>of</strong> Aboriginal<br />

and Torres Strait Islander communities, says a<br />

former colleague and Aboriginal community<br />

leader Sam Watson, the deputy director <strong>of</strong><br />

Queensland Aboriginal Communities at the<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Queensland.<br />

“People like Norm are developing important<br />

visionary concepts that are helping to provide<br />

a pathway to work with Aboriginal people.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> has taken a huge step here because<br />

this is groundbreaking work that will not only<br />

deliver outcomes to the Indigenous community<br />

but also create a broader awareness in the<br />

national academic community.”<br />

The CEO <strong>of</strong> the Link Up (Qld) Aboriginal<br />

Corporation, Dr Melisah Feeney, says that<br />

as a director <strong>of</strong> the organisation Dr Sheehan<br />

has shown a passion for helping improve<br />

the social and emotional wellbeing <strong>of</strong><br />

Indigenous people.<br />

Dr Sheehan and Dr Feeney are<br />

collaborating on an art initiative for<br />

Indigenous people in Queensland to express<br />

the healing power <strong>of</strong> ‘connectedness’.<br />

“Norm is an inspiring role model for<br />

Indigenous people. He has a deep insight and<br />

uses creative approaches to helping people<br />

learn about Indigenous ways <strong>of</strong> knowing and<br />

helping them to experience what it feels like<br />

to be excluded due to being in a minority,”<br />

Dr Feeney says.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Friedman says that he has long<br />

been keen to bring Dr Sheehan to <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s<br />

Faculty <strong>of</strong> Design. “I’ve been following<br />

Norm’s work and his approach to learning<br />

and design for a decade and I was keen to talk<br />

to him when we started looking for exciting<br />

scholars to attract to the university.”<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Friedman says that Dr Sheehan<br />

will be a valuable addition to an exciting<br />

new facility at the university. “The thing<br />

about Norm is that not only does he come<br />

with his considerable intellect and resources,<br />

but he also has a passionate community<br />

spirit. He is not just interested in having a<br />

narrow focus on his own area but has the<br />

generosity to work with and help other<br />

scholars.” ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 275 788<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

social inclusion<br />

7

swinburne <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

social inclusion<br />

8<br />

Cultural pride helps education<br />

start<br />

making<br />

sense<br />

A <strong>Swinburne</strong> TAFE program run in partnership with Aboriginal organisations in Victoria is<br />

helping to create some stability for disadvantaged Indigenous youths By Karin Derkley<br />

By age 15 Joe* had been expelled from<br />

two secondary schools for “inappropriate<br />

behaviour”. As an Indigenous teenager, and<br />

one with little family support, his life path<br />

may well have become the well-trodden<br />

one through the justice system and juvenile<br />

detention.<br />

Instead, Joe found his way into a<br />

specialist Indigenous educational training<br />

program for 15 to 24-year-olds – Mumgudhal<br />

tyama-tiyt (which translates as<br />

“message stick <strong>of</strong> knowledge”). The TAFE<br />

program, hosted by <strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong>’s TAFE division in partnership<br />

with the Victorian Aboriginal Community<br />

Services Association Ltd (VACSAL) through<br />

the Bert Williams Aboriginal Youth Services<br />

(BWAYS) in Thornbury, has recently<br />

been granted the Wurreker Award for<br />

achievements in training for Koorie students.<br />

Program convener and trainer Melinda<br />

Eason says Joe was with the program for<br />

six months in 2009 and is keen to finish<br />

the program in <strong>2010</strong>. Notably, he involved<br />

himself enthusiastically with the program’s<br />

practical approach to training and there was<br />

no sign <strong>of</strong> his previous reputation for violent<br />

and antisocial behaviour.<br />

When the course trainers told his mother<br />

how well Joe had been doing at the program,<br />

she cried, Ms Eason says. “She’d never had<br />

a teacher say anything good about her boy<br />

before.”<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> the young people who have<br />

attended the Mumgu-dhal tyama-tiyt<br />

program are the first generation in their<br />

family to be educated beyond primary<br />

school, says Anne Jenkins, a senior<br />

Indigenous education <strong>of</strong>ficer at the Centre<br />

for Engagement in Vocational Learning<br />

(CEVL) at <strong>Swinburne</strong>. “In mainstream<br />

schools the teachers are saying they’ve got<br />

enough to deal with; they haven’t got the<br />

time to deal with Aboriginal kids’ problems.<br />

But they don’t understand that for a lot <strong>of</strong><br />

these kids they are the first in their family to<br />

stay at school. It’s a big step.”<br />

Parents <strong>of</strong> Indigenous children can at best<br />

be ambivalent about the idea <strong>of</strong> education,<br />

says Miranda Madgwick, an Indigenous<br />

education <strong>of</strong>ficer with the program, who<br />

also received a Wurreker Award in 2009<br />

,,<br />

Teachers don’t<br />

have enough<br />

time or expertise<br />

to build the<br />

rapport with<br />

these kids that<br />

would reveal<br />

how much<br />

the kids are<br />

struggling.<br />

Hence the very<br />

high drop‐out<br />

rate for<br />

Indigenous kids<br />

in mainstream<br />

education.”<br />

Melinda Eason<br />

for Indigenous Teacher/Trainer <strong>of</strong> the Year.<br />

“They <strong>of</strong>ten have an issue with authority<br />

figures. They can’t understand why you’d<br />

want an education – they see it as a white<br />

man’s thing.”<br />

This is compounded by the way<br />

mainstream education alienates many young<br />

Indigenous people, Ms Eason says. “And<br />

teachers don’t have enough time or expertise<br />

to build the rapport with these kids that would<br />

reveal how much the kids are struggling.<br />

Hence the very high drop-out rate for<br />

Indigenous kids in mainstream education.”<br />

Many who attended the course at BWAYS<br />

had been completely sidelined by mainstream<br />

schools – either having been expelled<br />

or dropping out themselves. Some were<br />

residents <strong>of</strong> BWAYS hostel after becoming<br />

homeless or coming out from a spell in<br />

juvenile detention. Many were dealing with<br />

substance abuse in their families, others had<br />

the responsibility <strong>of</strong> looking after younger<br />

siblings. “These were very disadvantaged<br />

kids,” Ms Eason says. “So just getting them<br />

to class every day was a big achievement.”<br />

It’s a task that was carried out by the staff at

<strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong> swinburne<br />

illustration: Justin Garnsworthy<br />

BWAYS, who picked up many <strong>of</strong> the young<br />

people from their homes and also fed them<br />

lunch.<br />

The Mumgu-dhal tyama-tiyt program<br />

<strong>of</strong>fers Indigenous students training in<br />

Certificates I, II and III, which equip<br />

them with the basic skills needed to find<br />

employment. But unlike regular secondary<br />

schools and TAFEs it does this with as<br />

much focus on Indigenous culture as on<br />

literacy, numeracy and other employability<br />

skills, Ms Eason says. “It’s about cultural<br />

competencies and about seeing positive role<br />

models within the Indigenous community<br />

and about producing work that expresses<br />

their identity.”<br />

Part <strong>of</strong> the success <strong>of</strong> the course has<br />

been its partnership with other Aboriginal<br />

programs. These included ‘Koories in<br />

the Kitchen’ – a program developed by<br />

the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service,<br />

which teaches nutrition and hospitality<br />

skills and which culminated in the students<br />

preparing lunch during the ‘raising <strong>of</strong> the<br />

flag’ in NAIDOC week † – and MAYSAR<br />

(Melbourne Aboriginal Youth Sport and<br />

Recreation), which delivered a program<br />

to teach the students about responsible<br />

drinking, first aid and occupational<br />

health and safety. The students were<br />

also involved in a youth forum at the<br />

Aboriginal Advancement League,<br />

designed to hear the needs and<br />

wants <strong>of</strong> Indigenous youth during<br />

NAIDOC week. Other cultural<br />

projects carried out as part <strong>of</strong><br />

the course helped the students<br />

connect more closely to their<br />

local Indigenous communities.<br />

For many it was the first<br />

time they had been able to learn<br />

about their own culture in depth,<br />

says Shane Charles, Indigenous<br />

education support facilitator.<br />

“It’s been found that a strong<br />

grounding in their own culture<br />

gives Indigenous kids the security<br />

and self-esteem to move more<br />

comfortably into the mainstream.<br />

Conversely, Indigenous children who<br />

do not have a connection with their<br />

culture <strong>of</strong>ten show worse outcomes in the<br />

mainstream,” he says.<br />

Seventy-five per cent <strong>of</strong> students who<br />

started the course completed it, a result that is<br />

an achievement in itself, Ms Eason says. “Just<br />

the fact that these kids attended long enough<br />

to be able to graduate is a big deal, given their<br />

other responsibilities and life situations.”<br />

One graduate who has already gone on to<br />

bigger and better things is Leigh Pridham.<br />

He joined the program at age 19 after finding<br />

himself “going downhill”. “I’d been pretty<br />

unmotivated and I thought it might be a<br />

good way <strong>of</strong> getting myself back on track<br />

in a place where you feel comfortable with<br />

people you know,” he says.<br />

Leigh says he liked the way the program<br />

got him out doing things in the community,<br />

and working with other students to build<br />

their cultural understanding and skills. “It got<br />

my confidence back up – and got me back<br />

into the habit <strong>of</strong> getting somewhere on time.”<br />

The year paid <strong>of</strong>f for Leigh. He was taken<br />

on by Crown Entertainment Complex as<br />

part <strong>of</strong> its hospitality training program and is<br />

learning “everything to do with hospitality<br />

… I’m really in my element now,” he says.<br />

For others the achievements have been<br />

more modest, but no less significant. For<br />

Joe it’s simply the fact that he’s enthusiastic<br />

about returning to education in <strong>2010</strong>. For<br />

another student who arrived at BWAYS at<br />

the beginning <strong>of</strong> the year so traumatised he<br />

could barely look anyone in the eye, it has<br />

been a journey just to be able to communicate<br />

with others. “His big achievement was to<br />

escort elders to the stage during an Indigenous<br />

Award to cross-culture<br />

business program<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> TAFE’s partnership with several<br />

other organisations to develop Indigenous<br />

business governance skills has been<br />

recognised with a Business/Higher Education<br />

Round Table (B-HERT) Award in the category<br />

<strong>of</strong> Best Community Engagement.<br />

The Indigenous Business Governance<br />

Program – ‘Managing in Two Worlds’ – aims<br />

to develop the skills <strong>of</strong> directors <strong>of</strong> Indigenous<br />

corporations and senior staff working in the<br />

Indigenous community sector to help the<br />

organisations run effectively and with the<br />

usual accountability processes.<br />

The program acknowledges that directors<br />

and managers <strong>of</strong> Indigenous corporations<br />

need to be able to ‘work in two worlds’ – their<br />

community’s culture as well as within Western<br />

systems.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

partnered with several organisations to<br />

deliver the program including the Office <strong>of</strong><br />

the Registrar <strong>of</strong> Indigenous Corporations,<br />

the Department <strong>of</strong> Planning and Community<br />

Development – Aboriginal Affairs Victoria,<br />

Consumer Affairs Victoria, the Department<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Premier and Cabinet, South Australia,<br />

and Horizons Education and Development,<br />

Queensland.<br />

Through the partnership, more than 600<br />

people from over 300 organisations across<br />

most states and territories have taken part in<br />

this training since late 2005. About one-third<br />

have gone on to undertake accredited training<br />

at Certificate IV or Diploma level.<br />

Sharon Rice, <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s director <strong>of</strong><br />

learning in the School for Sustainable<br />

Futures, says the program will play a key<br />

role in building the capacity <strong>of</strong> Indigenous<br />

organisations and, through that, facilitate<br />

progress across a range <strong>of</strong> economic, social<br />

and cultural programs and objectives.<br />

B-HERT is a not-for-pr<strong>of</strong>it organisation<br />

that was established in 1990 to strengthen<br />

the relationship between business and higher<br />

education. It is the only organisation with<br />

members who are leaders in higher education,<br />

business, industry bodies and research<br />

institutions.<br />

– Karin Derkley<br />

organisation’s celebration evening at the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the year. There’s no way he would have<br />

been able to do that the beginning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

course,” Ms Eason says. ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 275 788<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

Key points<br />

In 2009, its first year, 75 per<br />

cent <strong>of</strong> students completed<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> TAFE’s specialist<br />

Indigenous training program<br />

Most were from highly<br />

disadvantaged backgrounds<br />

and many were the first<br />

in their family to gain a<br />

secondary education<br />

Run in partnership with<br />

the Victorian Aboriginal<br />

Community Services<br />

Association Ltd, through<br />

the Bert Williams Aboriginal<br />

Youth Services, the program<br />

was granted the Wurreker<br />

Award for achievements in<br />

training for Koorie students.<br />

Miranda Madgwick, an<br />

Indigenous education<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer with the program,<br />

also received a Wurreker<br />

Award in 2009 for<br />

Indigenous Teacher/Trainer<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Year<br />

For information on how you<br />

can support social inclusion<br />

initiatives at <strong>Swinburne</strong>, see<br />

page 23<br />

* Not his real name<br />

† NAIDOC (the National Aboriginal<br />

and Islander Day Observance<br />

Committee) fosters the contributions<br />

<strong>of</strong> Indigenous Australians in various<br />

fields. Celebrations and activities<br />

take place across the country during<br />

NAIDOC week, the first full week<br />

<strong>of</strong> July.<br />

social inclusion<br />

9

Indigenous TV:<br />

swinburne <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

colourful, creative and<br />

fighting to stay local<br />

indigenous media<br />

10<br />

Indigenous community television has played an important cultural and educational role in remote communities,<br />

but faces an uncertain future with Australia’s imminent conversion to digital television By Karin Derkley<br />

Key points<br />

Locally produced<br />

Indigenous television has<br />

flourished despite limited<br />

resources<br />

Remote Australia’s<br />

conversion to digital<br />

television in 2013 will<br />

require 2.4-metre-wide<br />

satellite dishes to be<br />

installed on every house<br />

Satellite delivery will<br />

eliminate local program<br />

distribution when analogue<br />

television ends<br />

illustration: Justin Garnsworthy<br />

In 2009 at Pilbara<br />

and Kimberley<br />

Aboriginal Media<br />

(PAKAM)<br />

in Broome,<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Technology</strong><br />

researcher Dr Ellie<br />

Rennie watched as<br />

Indigenous media<br />

worker Henry Augustine<br />

loaded 67 videos on to a<br />

hard drive and prepared to<br />

drive by car 120 kilometres north<br />

to the Aboriginal community <strong>of</strong> Beagle Bay.<br />

The programs had been produced by the<br />

organisation over the past seven or eight<br />

years, and most were just a few minutes long<br />

– sport programs, cooking and public health<br />

programs, videos <strong>of</strong> hunting and ceremony,<br />

music clips <strong>of</strong> local rock and reggae bands.<br />

Mr Augustine was driving north at the<br />

request <strong>of</strong> the Beagle Bay community. The<br />

people there, like those in many other remote<br />

Indigenous communities around Australia,<br />

craved the chance to see these records <strong>of</strong><br />

their local everyday life, <strong>of</strong> ceremony and<br />

<strong>of</strong> community education on their TV sets.<br />

Mr Augustine’s job was to plug the hard<br />

drive into a computer at the Beagle Bay<br />

Remote Indigenous Broadcasting Station to<br />

send the programs out on a local television<br />

channel to the town’s 250 residents.<br />

Making and watching local television<br />

such as this has become an integral part<br />

<strong>of</strong> community life in remote Aboriginal<br />

communities, particularly in northern<br />

Australia. But when the plug is pulled<br />

in 2013 on analogue transmission, these<br />

communities will lose control over their<br />

local television stations.<br />

For Dr Rennie, a research fellow at<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Institute for Social Research,<br />

her work to explore the significance <strong>of</strong> local<br />

media production for remote Indigenous<br />

communities could see her documenting<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> a unique media system that has<br />

become the victim <strong>of</strong> new technology.<br />

Aboriginal communities had been making<br />

and distributing local videos since the 1980s,<br />

starting with pirate (unlicensed) television<br />

stations at Yuendumu and Ernabella, until<br />

the Australian Government responded by<br />

allocating community broadcasting licences.<br />

The compact all-in-one radio and television<br />

stations that followed were designed to allow<br />

local control over the retransmission <strong>of</strong><br />

satellite content and to provide communities<br />

with the means to produce and broadcast<br />

local programs.<br />

Today, larger media organisations –<br />

remote Indigenous media organisations –<br />

have taken responsibility for these smaller<br />

stations, with eight large organisations and<br />

150 smaller stations operating in remote<br />

Australia.<br />

As most communities did not have the<br />

capacity or resources to run local television<br />

stations on their own, these large media<br />

organisations developed content-sharing<br />

networks, such as the Indigenous Community<br />

Television (ICTV) channel, which provided<br />

a programming feed. Communities that still<br />

wanted to screen local content could insert<br />

programs into the schedule. In this way<br />

Indigenous media was able to develop an<br />

alternative model <strong>of</strong> media production and<br />

distribution to mainstream broadcasting.<br />

Dr Rennie says these programs have<br />

played an important role in remote<br />

communities. “Very <strong>of</strong>ten they are basic<br />

records <strong>of</strong> daily life, but it is a daily life<br />

that is completely different from the rest<br />

<strong>of</strong> the country.” Some videos are intended<br />

to maintain culture, she says. For instance,<br />

a recent video <strong>of</strong> a ceremony told in three<br />

different Aboriginal languages – Ngarti,<br />

Kokotha, and Walmatjarri – was produced<br />

partly as a resource for young people.<br />

The act <strong>of</strong> video production in itself is<br />

also helping to keep young people involved<br />

in the maintenance <strong>of</strong> traditional life,<br />

Dr Rennie says. However, the opportunity<br />

for communities to make and watch these<br />

programs has been placed under threat.<br />

In 2007, at the Australian Government’s<br />

direction, the ICTV service was replaced by<br />

National Indigenous Television. It operates<br />

via satellite, leaving remote communities<br />

without a distribution platform. While a few<br />

remote broadcast stations were inserting<br />

some community programming locally, most<br />

went without. However, there was some<br />

good news, with ICTV’s return in November<br />

2009, with help from the Western Australia<br />

Government’s Westlink satellite channel,<br />

made available on weekends.<br />

The second setback is digital<br />

broadcasting. Inserting local content over<br />

either the older ICTV or its newer version<br />

National Indigenous TV will not be possible<br />

after 2013 when analogue television is<br />

switched <strong>of</strong>f.<br />

In January <strong>2010</strong> the Australian<br />

Government announced that only a portion<br />

<strong>of</strong> transmitters in regional Australia will be<br />

converted to digital, but that subsidies for<br />

domestic satellite dishes will be available for<br />

homes where there is no terrestrial service.

<strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong> swinburne<br />

That means that the television transmitters<br />

used by local, analogue, remote Indigenous<br />

broadcasting stations will be made redundant<br />

and television in many communities will be<br />

delivered by satellite only.<br />

Inserting community-made programs over<br />

the top <strong>of</strong> analogue channels is relatively<br />

straightforward, Dr Rennie says. “But it’s<br />

impossible for a local community to take<br />

control <strong>of</strong> a satellite signal being delivered<br />

direct to people’s homes.” The eight remote<br />

Indigenous media organisations now<br />

operating are hoping that the government<br />

will at least reinstate a full-time satellite<br />

channel for the Indigenous Community TV<br />

station, which would allow each region<br />

to control a portion <strong>of</strong> the programming<br />

schedule.<br />

Installing dishes on the ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> each<br />

<strong>of</strong> the homes in these communities, and<br />

maintaining them over their lifespan,<br />

will also be a massive task, with research<br />

showing that all homes in the remote north<br />

will each need a 2.4-metre dish on their ro<strong>of</strong><br />

to receive digital television rather than the<br />

90-centimetre dish needed for urban regions.<br />

Although the National Broadband Network<br />

will one day provide alternative means <strong>of</strong><br />

distribution, broadband speeds in remote<br />

areas are likely to be far slower than in the<br />

cities and even where broadband speeds<br />

are adequate, subscription costs may be<br />

prohibitive.<br />

Linda Chellew, media manager <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Indigenous Remote Communications<br />

Association, says that Dr Rennie’s work<br />

is playing an important role in examining<br />

and describing the significance <strong>of</strong><br />

Indigenous television to remote Indigenous<br />

communities. The association is the peak<br />

body and resource agency for remote<br />

Indigenous media organisations, representing<br />

more than 150 remote and very remote<br />

communities that broadcast television and<br />

radio Australia-wide.<br />

The much-vaunted National Indigenous<br />

TV, while appreciated, has an urban focus<br />

that has little relevance to people living in<br />

remote areas, Ms Chellew says. “The life<br />

and experiences <strong>of</strong> Indigenous people in<br />

remote areas bears little connection to that <strong>of</strong><br />

people in urban areas.<br />

“The government doesn’t seem to<br />

understand the importance <strong>of</strong> these<br />

communities being able to see programs and<br />

receive information about services and issues<br />

in their own language, presented by people<br />

who are part <strong>of</strong> their own value system.<br />

Hearing your own language on television<br />

is essential to community wellbeing. These<br />

remote peoples need programs that are<br />

driven by their own community issues rather<br />

The <strong>Swinburne</strong> project aims to:<br />

examine the structure and role <strong>of</strong> remote<br />

Indigenous media organisations and their<br />

networks within communities;<br />

reveal how community media organisations can<br />

assist in promoting communications uptake<br />

and use;<br />

monitor developments at the national level;<br />

examine tensions between low-cost community<br />

content and (high-end) national media<br />

industries and the role <strong>of</strong> both in innovation;<br />

investigate the impact <strong>of</strong> local Indigenous<br />

content;<br />

develop research approaches to better<br />

understand the place and use <strong>of</strong> communitybased<br />

media within the broader mediascape; and<br />

produce a book on the prospects for cultural<br />

and technological innovation via the Indigenous<br />

media sector.<br />

than by national concerns.”<br />

Another issue is the dire need for better<br />

resources and funding for video production.<br />

“The remote sector has always been treated<br />

by government as an amateur and marginal<br />

sector,” Dr Rennie says. “But the mediamakers<br />

<strong>of</strong> remote Australia are doing<br />

incredibly important work. There are women<br />

and men who are dedicating their lives<br />

to cultural maintenance and community<br />

education, and they’re hamstrung by the<br />

stereotype that they are just playing around.”<br />

People like Mr Augustine are training<br />

people in the skills to produce and transmit<br />

content with meagre resources at their<br />

disposal. The equipment essential for<br />

transmitting programs is <strong>of</strong>ten housed in<br />

hot and airless huts unsuitable for such<br />

technology. Meanwhile there are thousands<br />

<strong>of</strong> hours <strong>of</strong> video and film and thousands<br />

<strong>of</strong> photographs deteriorating for lack <strong>of</strong> the<br />

resources to properly catalogue and archive<br />

them. “There is so much work that needs to<br />

be done,” Ms Chellew says. “And so much<br />

value that could be gained by training young<br />

people in these important multimedia skills.”<br />

For Dr Rennie, the bittersweet aspect<br />

<strong>of</strong> her research at <strong>Swinburne</strong> is the fact<br />

that she may be documenting the end <strong>of</strong> a<br />

unique media system. “It is tragic that the<br />

model <strong>of</strong> remote television that has evolved<br />

since the mid-1980s – based on community<br />

ownership, grassroots organisation and<br />

regional collaboration – could soon be a<br />

thing <strong>of</strong> the past.” ••<br />

Contact. .<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Technology</strong><br />

1300 275 788<br />

magazine@swinburne.edu.au<br />

www.swinburne.edu.au/magazine<br />

WANT PROOF<br />

THAT WE<br />

GO BEYOND<br />

THEORY?<br />

YOU’RE<br />

HOLDING IT.<br />

Put theory into practice with<br />

a postgraduate course at <strong>Swinburne</strong>.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> academics are more than just that. Many <strong>of</strong> them<br />

are industry-proven pr<strong>of</strong>essionals with years <strong>of</strong> experience,<br />

ready to impart real-world learnings onto the next generation<br />

<strong>of</strong> industry leaders.<br />

POSTGRADUATE STUDY<br />

1300 ASK SWIN<br />

swinburne.edu.au/postgrad<br />

CRICOS Provider: 00111D SUT1256/30/C

swinburne <strong>March</strong> <strong>2010</strong><br />

astronomy<br />

12<br />

By observing pulsars, researchers hope to discover the most elusive waves in space and,<br />

with that knowledge, gain new insights into the universe By Julian Cribb<br />

Sarah Burke-Spolaor (left) and Lina Levin, PhD students at <strong>Swinburne</strong>’s Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing.<br />

<strong>Swinburne</strong> astronomers are engaged in a<br />

quest to discover the most elusive waves in<br />

the universe – Einstein’s gravitational waves<br />

– using the largest ‘instrument’ imaginable:<br />

an array <strong>of</strong> burnt-out giant stars that are<br />

spinning hundreds <strong>of</strong> times a second.<br />

Predicted in Einstein’s theory <strong>of</strong><br />

relativity, gravitational waves are vast<br />

echoes in space-time thought to be<br />