Next Level Violinist promo

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

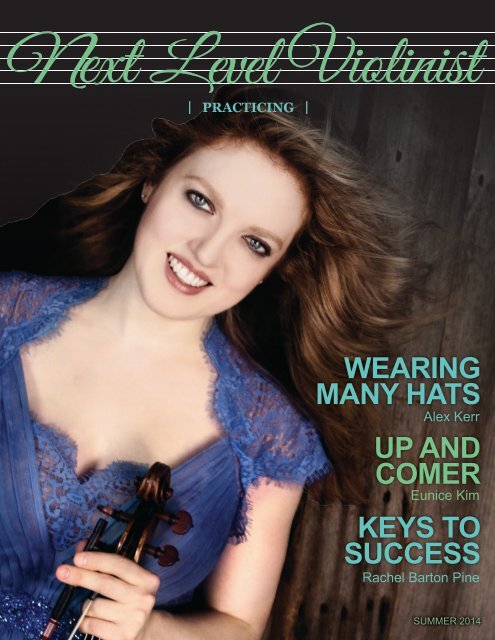

| practicing |<br />

Wearing<br />

many hats<br />

Alex Kerr<br />

up and<br />

comer<br />

Eunice Kim<br />

keys to<br />

success<br />

Rachel Barton Pine<br />

summer 2014

Contents<br />

Summer 2014<br />

Feature Story<br />

5 Wearing Many Hats<br />

Alex Kerr<br />

11 Up and Comer<br />

eunice kim<br />

16 Keys to Success<br />

rachel barton pine<br />

Contributors<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

PUBLISHER / FOUNDER<br />

Brent Edmondson<br />

editor<br />

Edward Paulsen<br />

SALES<br />

Karen Han<br />

Layout designer<br />

2 NOV/DEC SUMMER 2013 2014 NEXT LEVEL BASSIST VIOLINIST

Publisher’s Note<br />

It’s utterly thrilling to be writing you from the pages of <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> <strong>Violinist</strong>!<br />

This journal represents the culmination of months of planning to create a<br />

resource that I hope every violinist will read and take to heart. Inside this issue,<br />

incredible teachers and players will lay out the tools that you need to be,<br />

as Rachel Barton Pine puts it, “a professional practicer.” That’s really what music<br />

comes down to: how can you develop your technique and your understanding<br />

of the instrument so it becomes the most natural way to express yourself?<br />

I recall my early days of learning to play. I would practice the bare minimum that my<br />

parents told me to, and fought them nearly every step of the way. One day, a friend of<br />

mine came over and showed me how to play a boogie-woogie bass line on the piano.<br />

Once I had learned to play it, I was suddenly hooked. There wasn’t enough time in<br />

the day for me to practice as much as I wanted to. Finding jazz, discovering a side<br />

of music that inspired and pushed me to play better every day, these were the catalysts<br />

for my growth. Over the years, I learned how to refine my practicing and learn more<br />

material in shorter periods of time, adding tips and tricks to my ever-growing arsenal.<br />

As we make the transition from students to professionals, we inevitably find less and<br />

less time to isolate ourselves and truly focus on practicing. Turning off our phones,<br />

switching off the TV, and really centering our minds on the music at hand is one of<br />

the skills that separates musicians from the general population. For me, practice is<br />

almost meditative. I find that I have my best ideas during or right after practicing.<br />

It is one of the most clear channels for thinking that I have developed in my brain,<br />

and it can and should be the same for you as well.<br />

As you read through the brilliant advice laid out by Rachel Barton Pine, one point<br />

of focus is her innovative way of strategizing so she keeps all facets of her playing<br />

fresh and honed at the same time. I am smitten with her idea of practicing scales in<br />

a “Debussy” style, or polishing your Mozart tone with scales while you are focusing<br />

on preparing Brahms for performance. Her organizational principles underscore the<br />

strong need to be an efficient practicer and use the limited time you have to maximize<br />

your results.<br />

Alex Kerr, who is a wonderful and well-rounded violinist, provides so many fantastic<br />

links and reference points for developing your skills as a player. Take each one to<br />

heart and you may just find yourself with the same extensive resume of high-ranking<br />

positions that Alex has accrued. Additionally, I think his points on reading to broaden<br />

your horizons are right on the money. One of the best ways to improve yourself as a<br />

musician is to improve yourself as a person. Once you have developed your technique,<br />

you will find that the extracurriculars of life (such as knowledge, friendships, and<br />

love) will give you more to say in your playing.<br />

I’m glad you’ve joined us on our initial issue of <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> <strong>Violinist</strong>. Keep searching<br />

for ways to improve your playing, your understanding, and your love of music, and<br />

nothing will stand in your way. I’ll check in with the next issue, and look forward<br />

to seeing you on the <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong>.<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Publisher <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Journals<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST<br />

3

4 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST

wearing<br />

many hats<br />

Alex Kerr<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST<br />

5

At this point in my life I have so many roles to play - professor, concertmaster, soloist, chamber musician, father, husband -- all of<br />

these things take an incredible amount of time. The fact is, any one of these by themselves would be enough to fill one’s emotional<br />

and physical cup! Therefore, everything I do has to be done in a meticulous and extremely conscious manner. When I’m performing<br />

as a chamber musician, it has my complete attention, as do all of my different personas. When I’m practicing, I have to be intensely<br />

focused because I have a finite amount of time per day and per week. I’m having to learn a substantial amount of music on an hour to two hours<br />

a day of practicing, if I’m lucky! My practicing has to be so meticulous and organized that I’m not wasting a single second. I’m very regimented<br />

in what I’m working on, what I’m looking for, and how I’m going to accomplish it. If I’m not, I won’t achieve what I want to accomplish and that’s<br />

wasting time I don’t have. My practicing relies on organizational skills and a clear focus on the certain things that need to be addressed.<br />

Although I wouldn’t call myself an “etude person,” I use specific etudes for certain overarching concepts that I think are important. A typical<br />

warmup for me would be practicing Sevcik op. 1 no. 1 left hand etudes, which are useful for the frame of my hand, agility, the speed of the drops<br />

of my fingers, and the angle of the drops.<br />

Sevcik Op. 1 No. 1<br />

I also use scales for these purposes, adding the complexity of vibrato and shifting. I’ll go from there to practicing the Yost etudes - basic shifting<br />

etudes that are out of print but available on IMSLP. Throughout all of this, I’m focusing on producing a beautiful sound, the contact point<br />

between fingerboard and bridge, and getting focused for what I’m about to practice. There are certain elements that are key no matter what you<br />

are working on. The only thing that changes is the context. If I can focus on those basic principles in a simplified form, then I can take them<br />

and bring them into the solo repertoire.<br />

Yost Exercise No. 1<br />

6 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST

Schriadieck exercises are a great resource when it comes to building<br />

the frame of the left hand, intonation, and agility. Kreutzer is another<br />

one - Josef Gingold was absolutely right when he said you never finish<br />

Kreutzer! I think of the Paganini Caprices as competition pieces, or<br />

perhaps the “final etudes.” The Ernst pieces or the Wieniawski pieces<br />

go into this category as well: pieces you play when you have the basics<br />

and you’re trying to hone them to the point where you can do anything<br />

on the instrument. There are things on the way from Kreutzer to a<br />

Paganini - Rode and Gavinies are very nice, but the most important<br />

thing is you have to know what you’re trying to achieve. The etude<br />

is there to address a specific issue, so if you’re going through the book<br />

reading the notes without trying to discover the issue that you’re<br />

trying to address, you’re missing the point and wasting your time.<br />

working hard. The outside material is much more difficult to achieve,<br />

and honestly impossible to achieve if you’re not focused on what<br />

you’re doing. Here are some ways to get the most of your time seeking<br />

the “bread” of this sandwich.<br />

When working on intonation, always practice with a drone - specifically<br />

the lower open string of two. I find that people who use a tonic drone<br />

end up with a different tuning because we are tuned in fifths and not<br />

in octaves. I always try to temper my intonation. Practicing intonation<br />

without a drone is exceedingly difficult and pointless.<br />

I always make sure that my body is as relaxed as possible, because<br />

tension is the worst enemy of the musician. It’s tension that we’re<br />

trying to address, because anytime we get on stage, nerves are the<br />

effect of it. Addressing tension cannot only happen on stage. It’s not<br />

Rode excerpts from Etudes 1 and 4<br />

Every student has to have the mentality that they’re listening to themselves<br />

with the ears of someone who doesn’t like them. People get too<br />

comfortable in the practice room. I practice always with the thought<br />

process that I’m going to have to play this stuff in public. Practice must<br />

always be solution oriented, or else, again, it’s a waste of time. I tell my<br />

students to constantly listen to themselves. Technique is the means<br />

to the musical end; it is not merely a math equation to decipher<br />

(even though we work from physics and athletics). Sound and music<br />

dictate everything, therefore not knowing what you want to sound<br />

like and not knowing what you want to do musically creates too many<br />

variables. These have to be thought out first, and then everything else<br />

is teachable.<br />

If you think of music as a sandwich, the bread is the difficulties. One<br />

slice is knowing what you want in the first place, and the other slice is<br />

knowing when it’s right. This is aesthetics and hearing. All the meat,<br />

cheese, mayonnaise in the middle is teachable, and it all comes from<br />

a spontaneous act - one has to actively practice releasing tension in<br />

order to make it occur on stage. I’m always working on releasing my<br />

joints, getting the proper weight into the strings from both hands,<br />

and always doing so in a manner that is efficient and avoids locking<br />

any of the joints in the arm or neck.<br />

When it comes to sound quality, I believe the contact point is one<br />

of the most fundamental elements of being a good and consistent<br />

violinist. A control over a variety of contact points for different<br />

contexts is literally one of the things that separates a great violinist<br />

from a mediocre one. I was never told this in a scientific manner.<br />

I think that a lot of the great violinists of the bygone era were trained<br />

very well at a very young age and didn’t have much inward analysis<br />

of what they were doing. I always thought of myself as a late bloomer,<br />

someone who needed to fully understand things to make them work.<br />

I read books on physics, acoustics, the human body, Alexander<br />

technique, physical therapy, and others to further this understanding.<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST<br />

7

Guy Voyer, a French osteopath, is a genius in<br />

showing stretches that keep one from getting<br />

too tight and allows one to maximize use of<br />

the body.<br />

I’m constantly dividing my practice focus<br />

between intonation, sound, and relaxation. I<br />

also consistently practice with my metronome.<br />

I think of the metronome not just as something<br />

I need to stay with, but as my pianist, as<br />

my orchestra. It’s something that keeps me in<br />

check with the music, with the overall pulse.<br />

I don’t think of it as a crack addict needing<br />

his pipe, I let it reflect my tendencies so I can<br />

see more about myself. It’s a much different<br />

mentality - you’ll always find people who<br />

practice with a metronome and upon leaving<br />

it behave like Linus having lost his blue<br />

blanket, or Moses being lost in the desert.<br />

They’ve removed the one map they had, rather<br />

than using the map to create an internal map.<br />

That’s the point of using the metronome.<br />

Take the external beat and use it to understand<br />

your internal beat. It’s not natural to us, so<br />

we need to use this technology to try and<br />

create something from within that’s as close<br />

to it as possible. One of the things I’m naturally<br />

good at is phrasing. I’ve always had a natural<br />

way of feeling music. Let’s say there’s a person<br />

who isn’t natural at it. For this person, I like<br />

to take all distractions away, removing vibrato<br />

and all other external elements. Just phrase<br />

with the bow. Analyze how the phrase works.<br />

Listen to recordings to figure it out. If someone<br />

doesn’t have access to theory classes, harmony<br />

training, music history classes, etc. they<br />

can look at the score while listening to the<br />

recordings. I encourage students not to listen<br />

to a single recording, but to listen to 15! Get<br />

hundreds of ideas going through your head.<br />

I remember studying the Debussy sonata, and<br />

I was listening to a recording of Frank Peter<br />

Zimmermann. I was getting so many ideas<br />

from it! I listened to a dozen other recordings,<br />

but I still found Zimmermann’s interpretation<br />

resonated most strongly with me. There was<br />

something organic about it. I learned it and<br />

performed it, and then I listened to the tape<br />

of the recital. I was relieved and inspired to<br />

find that it was completely different from<br />

Zimmermann - I wasn’t imitating him in<br />

the slightest. He started me on the path to<br />

thinking about certain things, and yet I totally<br />

diverged from him. That’s what the benefit<br />

of listening is - I completely disagree with<br />

people who encourage students not to listen<br />

to recordings. I think you should listen to<br />

hundreds of them. Find out what you like,<br />

find out what you don’t like! I’m always<br />

amazed as a professor that a resource like<br />

Youtube exists where you can go listen to all<br />

8 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST<br />

the great violinists of the recording era, and<br />

yet all people do is look at cat videos, and<br />

don’t use it as the resource that it could be -<br />

not even to cheat with fingerings! I offer my<br />

fingerings and bowings to students, but I don’t<br />

want them to become addicted to them, so I’ll<br />

make them create their own. They’ll come in<br />

and say they are so confused, and I’ll wonder<br />

why they didn’t just go look at a video of<br />

Leonidas Kavakos to see what he was doing!<br />

People don’t really see that these basic<br />

resources are so tangible that you could touch<br />

them. I would have used everything at my<br />

disposal at that age. We used to go to concerts,<br />

buy the nosebleed seat tickets, and run down<br />

to the stage when the soloist would come<br />

on so we could analyze every fingering and<br />

bowing. We don’t even need to do that anymore<br />

- use the technology at your fingertips!<br />

I used to listen to a lot of violinists, which I<br />

think made me improve rather quickly. The<br />

negative aspect of this was that I didn’t have<br />

as much knowledge as I did will power!<br />

Michael Rabin, my teacher Aaron Rosand,<br />

Itzhak Perlman, David Oistrakh, Jascha Heifetz<br />

- I wanted so much to be as good as all of<br />

these people, which made me improve by<br />

sheer will! There were certain things that<br />

were natural for me, but other concepts were<br />

completely foreign to me; I felt lost. Technically,<br />

things like contact<br />

point weren’t<br />

presented to me<br />

because teachers<br />

assumed I already<br />

knew. I became so<br />

envious of all the<br />

violinists around me<br />

that were so much<br />

more consistent<br />

than I was; this was<br />

a feeling I still had<br />

into my 20s, even<br />

after I had already<br />

won positions in<br />

prestigious<br />

orchestras! I hadn’t<br />

yet achieved a total<br />

understanding of<br />

violin playing; it<br />

came later as I<br />

began teaching<br />

and developing a<br />

consistent method<br />

that I believed in.<br />

I researched everything,<br />

read every<br />

single book you<br />

can imagine. This<br />

extended beyond the<br />

music.indiana.edu<br />

literature on how to teach and play violin<br />

and into physics, natural science, and beyond.<br />

I developed a method for doing what I was<br />

doing in a consistent manner. I realized my<br />

whole life had been a process leading to these<br />

realizations. In the end, knowing what I wanted<br />

to be when I was young made it easy to get<br />

some recognition quickly, but it made my<br />

overall journey more complex because I gave<br />

people the impression that I knew what I was<br />

doing when I really didn’t.<br />

Not everybody loves what they do. Some<br />

people think they do but being a musician<br />

means loving to do even the things that<br />

aren’t as artistically rewarding as the most<br />

invigorating concerts. One has to be fascinated<br />

by the violin, to enjoy the most mundane<br />

tasks and even one’s worst days. I love being<br />

a concertmaster, playing in an orchestra,<br />

playing chamber music, every day.<br />

When kids are young and they’re trying to<br />

learn, they’re always searching for something<br />

to hold onto. They need to realize that there<br />

are resources out there, and that in the end,<br />

achieving a quality and consistent technique<br />

is really doable. I actually find now that the<br />

most difficult thing one can do on the violin<br />

is learning how to do what you did in the<br />

practice room in front of 2,500 people every<br />

MORE than 170 artist-teachers and<br />

scholars comprise an outstanding<br />

faculty at a world-class conservatory<br />

with the academic resources of a<br />

major research university, all within<br />

one of the most beautiful university<br />

campus settings.<br />

STRING FACULTY<br />

Atar Arad, Viola<br />

Joshua Bell, Violin (adjunct)<br />

Sibbi Bernhardsson, Violin,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Bruce Bransby, Double Bass<br />

Emilio Colon, Violoncello<br />

Jorja Fleezanis, Violin,<br />

Orchestral Studies<br />

Mauricio Fuks, Violin<br />

The Pacifica Quartet performs<br />

as quartet-in-residence.<br />

Simin Ganatra, Violin,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Edward Gazouleas, Viola<br />

Grigory Kalinovsky, Violin<br />

Mark Kaplan, Violin<br />

Alexander Kerr, Violin<br />

Eric Kim, Violoncello<br />

Kevork Mardirossian, Violin<br />

Kurt Muroki, Double Bass<br />

Stanley Ritchie, Violin<br />

Masumi Per Rostad, Viola,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Peter Stumpf, Violoncello<br />

Joseph Swensen, Violin<br />

Brandon Vamos, Violoncello,<br />

Pacifica Quartet<br />

Stephen Wyrczynski, Viola (chair)<br />

Mimi Zweig, Violin and Viola<br />

2015 AUDITION DATES<br />

Jan. 16 & 17 | Feb. 6 & 7 | Mar. 6 & 7<br />

APPLICATION DEADLINE Dec. 1, 2014

night. The other parts are teachable, and there are resources and basic<br />

things that can help. When you are aware of these, you can manage<br />

your own progress.<br />

Vibrato<br />

Let’s talk about vibrato. The components of vibrato are very simple:<br />

it’s one part arm, one part wrist, one part the first joint of each finger.<br />

The arm is basically a spark plug - it gets things moving. If you want<br />

to talk about what controls the width and speed, it’s much more the<br />

first joint of the fingers. Go on Youtube, watch Ivry Gitlis. There are<br />

two videos of him playing the Rondo Capriccioso by Saint-Saens.<br />

One recording is when he was about 35 years old and the other is<br />

from when he was 88. Observe how his wrist is not straight but slightly<br />

out when he vibrates. The reason for this is he keeps the weight of his<br />

hand forward and he’s able to vibrate quite big with the joint without<br />

taking his finger weight off the string. Ivry always got violinists to<br />

think outside the box, and some people might take issue with his<br />

interpretations; however, one thing you can’t argue with is that he has<br />

the same vibrato across his entire career, 50 years later. How many<br />

people do you know that can do that? Probably no one! You simply<br />

can’t argue with the mechanics.<br />

Left hand articulation<br />

Watch Hilary Hahn’s performance of the final movement of the C<br />

Major Bach Sonata and observe how she drops her fingers from the<br />

base knuckles. Look at how every finger is independent within that<br />

frame, how she gets a lot of finger weight from the acceleration of the<br />

fingers into the string. There’s a reason she’s doing that, and it’s because<br />

it is efficient. She’s getting all the weight that’s necessary to make the<br />

string stop, but she gets most of it at those speeds from the acceleration<br />

of the drop. You can see the same mechanic in Julia Fischer’s left hand.<br />

Ruggiero Ricci used to say that a violinist is only as good as their<br />

intonation. I disagree with that because I’ve heard people play in tune<br />

and still be quite awful! I will admit that a violinist is only as good<br />

as their left hand, though. If your left hand is not at a very high level<br />

when it comes to using weight, using agility, using those gigantic<br />

drops, intonation, frame of hand - it doesn’t matter if your bow arm is<br />

fantastic, it’s not going to work. It’s very important to observe the great<br />

violinists of today - they all share many similarities in their left hands.<br />

Use videos as a resource to find what you need.<br />

Bow grips<br />

There are a lot of successful bow grips. You’ll see Franco-Belgian,<br />

Galamian grips, Russian grips, and hybrids of these. Each one presents<br />

certain advantages, especially if you look at the repertoire of the people<br />

who exemplify these various bow holds. If you’re talking Russian,<br />

basically Heifetz is the epitome. He was amazing for Romantic repertoire,<br />

but he wasn’t as successful in Classical and Baroque repertoire. Why?<br />

The Russian bow grip doesn’t lend itself to having a lot of “touch” -<br />

your joints are quite fixed and there’s not a lot of movement in the<br />

joints of the right hand. It makes it very difficult to produce a brush<br />

stroke, and that’s why Heifetz didn’t excel at that repertoire. Find out<br />

based on observation which grip you think is most effective. The<br />

thing that all grips have in common is the control over contact point.<br />

I challenge you to look at any violinist that’s good (any one of them!)<br />

- Frank Peter Zimmerman, Leonidas Kavakos, Julia Fischer, Joshua<br />

Bell, Gil Shaham - all of them have impeccable contact point control.<br />

They have all discovered, either consciously or subconsciously, that<br />

NEW ALBUM<br />

ONSALE<br />

NOW!!<br />

Featuring guest artists<br />

Joshua Radin,<br />

Branford Marsalis, and<br />

Jake Shimabukuro<br />

FIND OUT MORE AT TF3.COM<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST<br />

9

the more consistency they have over the contact point, the more consistency they’ll have<br />

over their sound in general. It’s important to observe what all great violinists do in the<br />

same manner.<br />

Finger Drops<br />

People get frustrated trying to learn how to play the violin, and want to do what they<br />

think makes sense, but sometimes the technique for getting good is counter-intuitive.<br />

Why would you think that using larger finger drops would help you play faster? It seems<br />

illogical, but in order to keep the hand relaxed and move quickly without making a fist,<br />

you need those larger drops so that the acceleration of your finger will give you the force<br />

you need to stay relaxed and press the string down. Force + mass = acceleration, it’s<br />

basic Newtonian physics. Technique can and must make sense. When you can approach<br />

the instrument with the knowledge of what you want to do, you can then employ your<br />

listening skills and logic to find which way to go. I’m sure there are teachers out there<br />

who tell students to keep their fingers extremely close to the string, and they are wrong<br />

because the physics are wrong. The thing that drives all of this information is music - this<br />

is why we do all this research to improve ourselves - physics provide a road map to make<br />

the journey easier. If you can combine that with a well-rounded knowledge of technique,<br />

you’ll get there faster and easier.<br />

Nerves and Anxiety<br />

One of the most crucial things about performing is being able to overcome the fight or<br />

flight response. You spend a lot of time training your body to relax, but the mind is going<br />

at a quick pace and it is subconsciously perceiving danger when you walk on stage. Your<br />

body wants to fight somebody or run, but there is nobody to fight and nowhere to run!<br />

All of your natural instincts at that moment are wrong. The first thing you can do is just<br />

drop your shoulders and let your arms hang at your sides. I strongly recommend reading<br />

the book Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. In this book, he identifies the ideal space<br />

where your body can relax. In my mind I think of this place as somewhere between<br />

boredom and frustration. The boredom component allows your body to relax and<br />

have weight in it. Frustration brings focus to your mind. Once your body is settled and<br />

relaxed, your focus can slow down and zero in on the music - that’s the easiest setting to<br />

perform in. This process may be easier some days and harder on others. Michael Jordan<br />

said that on his easier days, he felt like he was shooting an orange into a giant trashcan.<br />

Sometimes it feels like that, and sometimes you need to get out of there without falling<br />

on your ass. I deal with every situation the exact same way, whether I’m playing in<br />

Carnegie Hall or a nursing home. Sometimes I’m actually less nervous in Carnegie Hall<br />

than I am in my own living room. Another book that I find helpful is called Talent is<br />

Overrated. There are books by Daniel Pink that talk about the mind and how it works,<br />

and performance anxiety books by Don Greene.<br />

When it comes to tension and dealing with your body, it is so vital to treat your body as<br />

though you are an athlete. I would develop a stretching and exercise regimen that is low<br />

impact but high gain. I think all these things together can help one find one’s path. ■<br />

10 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST

Up and Comer<br />

eunice kim<br />

<br />

I truly have to thank my teachers, my colleagues, and my family<br />

for supporting me and believing in me. My teacher in San Francisco,<br />

Wei He, is definitely someone who understood me, nurtured me,<br />

and encouraged me to keep going, even through my difficult times<br />

of tendonitis and scoliosis. Getting into Curtis really changed my life,<br />

and I’m so grateful to my friends and teachers who made my 5 years<br />

there so meaningful. I’ve had so many people who brought me to<br />

where I am now, especially Ida Kavafian, who has been like a second<br />

mother to me. She is more than just a teacher- she is my role model<br />

and an inspiration to me. I’m lucky that I had the privilege of studying<br />

with her.<br />

I started playing when I was 6 years old. I had a babysitter from<br />

infancy whose son was the concertmaster of the San Jose Symphony<br />

in California. As a very young child, he was always practicing around<br />

me, and after years of listening to him I told my mother I wanted to<br />

play the violin. My mom was disappointed, because she had wanted<br />

me to play the cello. When the day came to get a cello, the people at<br />

the string shop told us I was too petite to start the cello, and they gave<br />

us the violin.<br />

Nowadays, you’re a member of the Astral Artists<br />

roster, a recent Curtis graduate, and you just finished<br />

playing solo with the Philadelphia Orchestra.<br />

What else is in the works for you?<br />

It was quite a year for me since it was my last year at Curtis, which was<br />

extremely bittersweet. I was the concertmaster of the Curtis Symphony<br />

Orchestra, and I had a lot of orchestral responsibilities. I performed<br />

constantly and collaborated with many great individual musicians,<br />

ensembles, and orchestras, which I hope to continue doing in the future.<br />

I was the violinist of Ensemble39, a contemporary ensemble that<br />

formed at Curtis. Now that I’m out of school, I have a lot of freedom to<br />

experiment with everything right now. I just came back from Ravinia’s<br />

Steans Institute, which was an amazing experience. I’m doing whatever<br />

is coming my way, and I think now is the time to do that. I don’t like<br />

the concept of “settling down,” rather I’m trying a variety of things out<br />

until I see what I want to do.<br />

Can you talk about your warmup routine?<br />

My “routine” differs every day, but I try to stick with a scale or two<br />

each day. Before college, I was very faithful to arpeggios, double stops,<br />

etudes, and those dreaded Paganini Caprices, but on very busy days<br />

where I don’t have an hour or two to work on warmups, I may start by<br />

picking up the violin and working on a difficult passage very slowly.<br />

One of my favorite ways to start the day, which I learned from working<br />

with my colleague and friend Tim Dilenschneider (see <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

Bassist Left Hand Issue), is to play some passages from Edgar Meyer’s<br />

Concert Duo. I thought it was so much fun playing his music that I’ll<br />

just go back to that at the beginning of the day. It’s probably pretty<br />

funny to listen to me warming up!<br />

Do you get nervous while performing? How do you<br />

deal with that?<br />

I absolutely do, but it’s always a “good” kind of nervous. I think<br />

performing gets more nerveracking as you grow older because your<br />

expectations grow as time goes on. The difference for me now is that<br />

I have embraced the fact that I will get nervous, and prepare myself<br />

for it. The day before or the day of the performance, I accept that I<br />

will get nervous, and I mentally prepare by telling myself that it is<br />

a good thing to be nervous since it means I’m just excited to perform.<br />

I physically practice by doing jumping jacks before I play a slow piece<br />

or movement, because that is always the hardest part - when your heart<br />

is beating fast and you have to have complete control over your body.<br />

I’ll also try putting my hands in the fridge for a second and then try<br />

to play the violin, because I sometimes get cold hands before I play.<br />

Pam Frank told me that it’s good to find ways to practice being nervous<br />

and deal with it, which has helped me a lot.<br />

What’s a typical day in your life?<br />

Every day lately has been very different! If I’m not traveling, I like<br />

to do my practicing in the morning to get it out of the way, and I’m<br />

typically off to rehearsal soon after. I deal with scoliosis, and tendonitis<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST 11

“it was a lot of work and a lot of anxiety imagining a career<br />

in music, but being apart from my violin and not being able<br />

to make music made me determined to really go through with<br />

this passion I had, and it clarified what I needed to do.”

comes very easily to me so I try to be as active<br />

as I can. I’ll either do some yoga or go swimming,<br />

whatever keeps me moving instead of<br />

sitting in front of my computer! If I have a<br />

concert that day, I like to keep my schedule<br />

light, but if I don’t, I will typically round out<br />

the day with some more practice time. When<br />

I’m traveling, I like to have travel days off.<br />

You need to let your body catch up on rest<br />

when traveling! I don’t like to be the person<br />

practicing a million hours a day - I know that<br />

I have to watch out for myself both physically<br />

and mentally. It’s no fun watching the walls<br />

of a practice room all day - but don’t tell my<br />

teacher that!<br />

What are some of your<br />

career highlights?<br />

Last week was very exciting for me, making<br />

my solo debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra.<br />

I had never played with a group like that<br />

before. Getting prepared for that was a little<br />

bit scary, because I had spent an intense<br />

5 weeks of chamber music at Ravinia. We<br />

were rehearsing 5-7 hours a day, which meant<br />

that I barely had the time to practice while I<br />

was there. I played at the Mann Center in<br />

Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, with a great<br />

crowd between 3,000 and 4,000.<br />

It was a very supportive crowd, even sitting<br />

on the lawn while it rained! When I came<br />

to the rehearsal, it was so amazing to see so<br />

many familiar faces - it was great to play with<br />

my favorite orchestra that I frequently listen<br />

to. I knew the conductor, having met him<br />

at Curtis. They were very supportive, and it<br />

made a stressful rehearsal flow nicely into<br />

a great concert. Upcoming for me is Music<br />

at Angel Fire in New Mexico for the next<br />

few weeks, performing as a guest artist with<br />

Roberto Diaz on a Europe/Asia Curtis on Tour,<br />

collaborating with BalletX in Philadelphia,<br />

playing my Astral Artists debut recital, and<br />

performing with the Louisville Symphony.<br />

Talk about taking a short amount<br />

of practice time to get something<br />

to a high level.<br />

I learned a lot from my teachers on how to<br />

learn pieces in a smart way, and not wearing<br />

yourself out by over practicing. This year was<br />

a great test of these skills, because there was a<br />

lot of repertoire to learn in a very short time.<br />

I would give myself 45 minutes to an hour to<br />

really hit spots, things I needed to work on.<br />

I would get the difficult things done first and<br />

then allow the less challenging spots to play<br />

themselves. Pinpointing the spots that were<br />

most difficult for me, I would give myself a<br />

few tries to get them right instead of trying<br />

them over and over again. If I didn’t get it<br />

right in those few tries, I would revisit the<br />

passage at a later time. This is another lesson I<br />

learned from Pam Frank, who was also dealing<br />

with injuries when she was a performer.<br />

That forces you to work efficiently instead of<br />

repeating mistakes again and again for five or<br />

six hours. When you find yourself repeating<br />

mistakes, you have to stop and give yourself<br />

time to rethink the problem. It also helps to<br />

think of difficult spots musically. The technique<br />

often comes easier if you are thinking of<br />

shaping the passage or phrase that is a<br />

troublesome spot.<br />

What do you hope will be<br />

the next steps in your career?<br />

I’m really loving what’s going on right now!<br />

I had the honor of graduating Curtis with the<br />

Milka Violin Prize, which is a grant given to<br />

a graduating student who is committed to<br />

participating in international competitions<br />

for the next year. Therefore, I will enter<br />

international competitions when I have the<br />

Join the <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Journals family<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> <strong>Violinist</strong><br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Cellist<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> Bassist<br />

Articles, interviews, sheet music, and other resources from the best players and<br />

teachers in the world -‐‐ and all for free. Sign up at www.nextleveljournals.com today!<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST 13

time to, take auditions, and continue to perform and work with all<br />

of the amazing people around me. Anything is really possible at this<br />

time, so I’m keeping an open mind to see what’s out there.<br />

Do you think you’d like to be a professor<br />

in the long term?<br />

I would love to do that, but I think it takes an extraordinary person to<br />

be both a performer and a professor. Again, I look up to Ida Kavafian<br />

and her husband, Steve Tenenbom. They have far busier lives than we<br />

do, but they are incredibly dedicated to their students. I absolutely<br />

admire how they’re still brilliant artists and traveling performers, yet<br />

find the time to teach at multiple schools and give so much attention<br />

to their students... Not to mention that they have prizewinning dogs<br />

who compete! I have a couple students now, and I can see how<br />

challenging consistency is with my traveling and performing schedule.<br />

It really sheds light on how amazing my teachers are. While I was at<br />

Ravinia, Ida was giving me a lesson on a piece she’s very fond of…<br />

through text messages! She was taking pictures of her left hand<br />

position on the violin, and then she would write out the fingerings<br />

on a piece of paper. These little moments are very special to me since<br />

I know how busy she is, and I hope to be like her someday.<br />

Can you talk about some<br />

breakthrough moments for you?<br />

I think the most important time for me was when I wasn’t playing.<br />

I graduated high school 2 years early, and I was about to audition<br />

for colleges at 16 years old. I got too carried away, tried to be involved<br />

in too many things, and overplayed. I went to three different chiropractors<br />

a day, and most of them told me I wouldn’t be able to play<br />

for at least a year or two, and one of them even said I should stop<br />

playing altogether! They weren’t sure if I would be able to go back to<br />

playing after such a long time off. It was very discouraging, but I was<br />

so lucky because I had a supportive teacher, Wei He, who gave me<br />

lessons without the violin during the entire year that I wasn’t playing.<br />

I realized during that year that I really wanted to pursue music. Before<br />

that, it was a lot of work and a lot of anxiety imagining a career in<br />

music, but being apart from my violin and not being able to make<br />

music made me determined to really go through with this passion I<br />

had, and it clarified what I needed to do. Once I had the ok to start<br />

playing the violin again, I could only play about 5 minutes a day for<br />

a month or two. I felt like I had lost everything I had learned over the<br />

past several years, and it was hard to relearn how to play the violin,<br />

but it was a very big breakthrough for me. I knew that making music<br />

was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life after that point. I’m<br />

almost thankful that this all happened, just because it finally was<br />

perfectly clear to me that I was in love with music.<br />

What advice would you give for aspiring musicians?<br />

First of all, go and attend a lot of concerts. Rather than being cooped<br />

up in a practice room, you can find a lot of inspiration and discoveries<br />

by listening to music. That was what kept me going during the year I<br />

wasn’t playing. I went to as many concerts as I could to stay motivated<br />

- that was where I found the reason to be a violinist. It’s very moving<br />

and uplifting to listen to amazing masterpieces in person. It’s more<br />

personal and intimate than listening to recordings through<br />

your earphones.<br />

Brahms Example 1<br />

Brahms Example 2<br />

14 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST

Stay humble, and respect your colleagues, teachers, and audiences.<br />

Don’t settle for “it’s good enough!” I find it very troubling when people<br />

are preparing for a concert and walk away saying that it’s good enough<br />

for “that” audience. You should go to your full potential and push your<br />

limits on everything you play. You will feel more fulfilled and satisfied,<br />

you will have grown more after each performance, and the audience<br />

will feel that way as well. This makes performing a lot more worthwhile.<br />

What is some of your favorite repertoire to perform?<br />

Lately, I’ve really been loving South American/Spanish music. On<br />

my Astral Artists recital in December, I’ll be performing works by<br />

Piazzolla, Ginastera, De Falla and Sarasate. The first time I discovered<br />

Piazzolla, I immediately fell in love with his voice. Something about<br />

this type of music is so liberating, so spoken, and in a way, very<br />

comforting. My father plays guitar, and my recital falls on his birthday,<br />

so I decided to do this mostly-South American program in honor of that.<br />

Aside from all of that, I love listening to and playing to Schubertwell,<br />

mostly listening to it because Schubert is so challenging to play!<br />

His works are all heart wrenchingly beautiful in both a simple and<br />

complex way. I can’t get enough of Schubert at the moment!<br />

Is there anything you don’t enjoy playing?<br />

I don’t really dislike any music, but there are some traumatic experiences<br />

that you don’t want to revisit any time soon. One example that comes to<br />

mind is the Brahms Violin Concerto. I was playing it in a competition,<br />

in the finals. I got nervous right before the performance, and I started<br />

with the cadenza instead of the opening section, and I am totally<br />

scarred now. I don’t want to deal with that piece for a while!<br />

Do you have any advice or thoughts for aspiring<br />

musicians?<br />

Keep your head up and don’t let disadvantages get to you. I was at a<br />

friend’s recital recently, a girl who started playing the cello at age 12,<br />

which is somewhat late for professionals. Shortly after she started<br />

playing, she decided to audition at Curtis as a practice for other<br />

auditions - she actually succeeded and got in. Even if you feel like<br />

you are at a disadvantage, keep trying because sometimes you can<br />

evolve quickly and do things you never expected.<br />

Keep your mind open too. I didn’t really explore many different genres<br />

for most of my career, but I met my friend Tim Dilenschneider and<br />

other bass players, and they introduced me to bluegrass and Edgar<br />

Meyer. That brought me to Piazzolla and my love for jazz, which sums<br />

up a lot of who I am today. You can be a classical musician and still<br />

experiment with all different types of music. Also, don’t just look for<br />

inspiration in music. Other expressions of art such as films, visual art,<br />

and dance are all part of our world too. This is sort of a secret,<br />

but I am obsessed with Broadway! ■<br />

Get started with<br />

the Sassmannshaus<br />

method!<br />

Early Start<br />

on the Violin<br />

Volumes 1–4:<br />

BA 9676–BA 9679<br />

BÄRENREITER<br />

www.baerenreiter.com<br />

More information:<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL www.sassmannshaus.com<br />

VIOLINIST 15

KEYS TO<br />

SUCCESS<br />

Rachel Barton Pine

Early Memories<br />

Early in my studies, I developed a method<br />

for researching my music. Whatever piece I<br />

was studying, I would go and find a biography<br />

of that composer. I would go to the media<br />

section of the library and see what else that<br />

composer had written. By the time I was a<br />

teenager, that extended to styles of music. I<br />

was shopping for sheet music one day and I<br />

found this edition of Corelli’s opus 5 sonatas<br />

that had not only the violin line, bass line and<br />

right hand realization for the keyboard, but<br />

also an extra pull-out with an ornamented<br />

version of the slow movements purporting<br />

to be Corelli’s own ornaments. Whether<br />

they were or not is debatable. Up until this<br />

point, at age fourteen, I hadn’t even heard of<br />

ornaments. I thought you just played the notes<br />

on the page. I sought out some specialists,<br />

a viola da gamba player and harpsichordist<br />

in town who knew all about this stuff. They<br />

introduced me to concepts of historically<br />

informed performance. I started using a<br />

baroque bow and learning how to write my<br />

own ornaments, working them out carefully<br />

ahead of time. After a number of years I<br />

started getting used to the style and did<br />

them extemporaneously.<br />

When I was working on Bruch’s Scottish<br />

Fantasy I was really curious about the folk<br />

tunes that were incorporated into his 19 th<br />

century romantic concerto. I went to the<br />

library and found all these books from the<br />

18 th century that had these tunes in them. I<br />

sought out a Scottish fiddler to show me how<br />

these tunes would have been played by fiddlers<br />

and incorporated those inflections back into<br />

the violin concerto. Bruch himself might have<br />

been a German romantic composer, but his<br />

dedicatee for the piece was Pablo de Sarasate,<br />

the great Spanish violinist. Despite being of<br />

Spanish descent, he spent a lot of time touring<br />

in Britain, including Scotland, and was very<br />

familiar with Scottish fiddling first hand. In<br />

fact, he wrote his own medley of Scottish<br />

fiddle tunes with orchestral accompaniment.<br />

Once those fiddle tunes are in your ear you<br />

can’t play those tunes any other way. The<br />

violinist for whom Bruch wrote the piece<br />

would have played in a more fiddle-y way<br />

so that’s the way I’ve played it ever since.<br />

Learning about many composers, and<br />

especially their dedicatees was a very big part<br />

of my musical journey. Unless the composer<br />

was a violinist and was writing music for<br />

personal use, he or she was writing for a<br />

violinist. Learning about that violinist’s<br />

musical personality, taste and way of playing<br />

is very important in being able to understand<br />

what the composer’s intentions might have<br />

been, and using that in crafting your own<br />

interpretation.<br />

I was able to be a member of the Civic<br />

Orchestra of Chicago. It’s a training orchestra<br />

of the Chicago Symphony for undergraduate,<br />

graduate, and postgraduate students who are<br />

aiming for an orchestral career. My aspiration<br />

was to be a soloist but I wanted the training<br />

and security of knowing how to play in a<br />

good orchestra in case my solo career didn’t<br />

work out. Being in the Civic Orchestra was<br />

the best thing for my solo and chamber music<br />

playing. I can’t say this strongly enough<br />

because so many young people, particularly<br />

violinists, don’t take orchestra seriously. I<br />

think it’s really sad because orchestra is so<br />

much fun. So many of them go into orchestra<br />

and don’t get as much pleasure out of it as<br />

they could. In Civic, we had the amazing<br />

opportunity to have so many of the great<br />

conductors who were coming to the Chicago<br />

Symphony. They would come in and not<br />

do just one rehearsal with us, they would<br />

do a couple weeks’ worth of rehearsals and<br />

perform with us. They would work with us<br />

on every measure of the piece, break it down<br />

and put it back together. This kind of training<br />

in the orchestral repertoire directly impacted<br />

my understanding of all classical music. If I<br />

had spent that many hours in my room only<br />

practicing the Brahms concerto, I would have<br />

missed the Brahms I learned about playing<br />

his 4 th Symphony. If I had been just practicing<br />

Paganini caprices, I wouldn’t know how to get<br />

up and play a concerto with an orchestra, or<br />

how the orchestra instruments interact with<br />

each other. I feel so lucky to have had that<br />

orchestra in my city, because the only other<br />

institution like it is the New World Symphony<br />

in Miami. Even when you are in a good youth<br />

orchestra, you need to take it seriously<br />

and not just learn your part. Look at the<br />

score, listen to the other instruments, use the<br />

opportunity to learn about that composer’s<br />

style and apply that to the other music he or<br />

she wrote. Symphonic works are the greatest<br />

works of the classical music literature -<br />

how can you be a true musician if you don’t<br />

appreciate and understand those works and<br />

relate them to whatever else you’re playing?<br />

Now, conductors find me easy to follow<br />

because I understand how to work with<br />

a conductor; I’ve sat in the orchestra when<br />

soloists have done rubatos that were impossible<br />

to play with. Playing inside the orchestra<br />

teaches you what works and what doesn’t. I<br />

try to only do things that are going to work.<br />

If you go back historically, to violinists from<br />

past generations, they weren’t living in a<br />

bubble only playing concertos. Joachim,<br />

Brahm’s collaborator, conducted one day and<br />

played string quartets the next day, played<br />

concertos the next day, and sat concertmaster<br />

from time to time. That’s not the way the<br />

profession is anymore, but he was one of<br />

the greatest soloists of his day because he<br />

was a well rounded musician.<br />

In my early twenties, I was on the faculty<br />

of the League of American Orchestra. They<br />

put together the National Youth Orchestra<br />

Festival which took place on the grounds<br />

of Interlochen. Several high school level<br />

orchestras sent in audition tapes and five<br />

were selected, including the Chicago Youth<br />

Symphony. After performing with their own<br />

conductor, they were randomly shuffled<br />

into five new orchestras, and each of those<br />

orchestras spent the week preparing a program<br />

with one of five famous conductors. These<br />

kids didn’t know which orchestra they would<br />

be in and they had a week to learn pieces like<br />

Shostakovich 6 or Mahler 1. I was there to<br />

coach the violins. The disconcerting thing<br />

was, I would walk past the wind and brass<br />

players in their rooms practicing their<br />

orchestra music, bass players, violists, cellists<br />

practicing their orchestra music, but you<br />

would hear the violinists practicing their<br />

concertos and Paganini caprices. I ripped into<br />

them, I asked them why they weren’t learning<br />

the music like their colleagues, when they<br />

didn’t know it any better than them. They<br />

argued that they had lessons with their teachers<br />

at home and needed to be prepared. I said,<br />

“well, I can’t help it if your teacher doesn’t<br />

understand the value of orchestra training but<br />

right now you’re here and we’re your teachers<br />

and we expect you to be prepared. I better not<br />

pass by the dorms and hear your practicing<br />

anything other than your symphony for the<br />

next couple of days.” It wasn’t totally their<br />

fault, if they did have those teachers saying<br />

“the day after you get back I expect your<br />

concertos to be ready for your lesson.” That<br />

was really revealing, that it was just the violins<br />

that were doing that.<br />

Organization is Key<br />

The majority of my gigs are standard, like<br />

a Tchaikovsky concerto one week, a typical<br />

recital with Romantic sonatas and a Classical<br />

period sonata and virtuoso piece one week,<br />

and then I might do a Mendelssohn concerto<br />

and then another Tchaikovsky. It’s all pretty<br />

standard repertoire with some unusual things<br />

peppered in. When I’m preparing repertoire<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST 17

18 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST<br />

I’ve played before, like the<br />

big concertos, there are<br />

three big factors that go<br />

into deciding how far in<br />

advance to start preparing<br />

it. One is the<br />

inherent difficulty of<br />

the piece. Some pieces<br />

are simply longer<br />

and more physically<br />

challenging than<br />

others. The other is<br />

how long it has been<br />

since I last played<br />

the piece, as well as<br />

how many lifetime<br />

hours I’ve played it.<br />

I also determine how<br />

much repertoire I’m<br />

performing before I have<br />

to perform that piece.<br />

I calculate all of those<br />

factors and work backwards<br />

to figure out when I have to<br />

start. I’ll realize that I have to<br />

start practicing this piece for<br />

three weeks from now and this<br />

other piece for six weeks from<br />

now, but actually, I don’t have to<br />

start the piece two weeks from<br />

now until next week because<br />

it’s easy and I just played it last<br />

month. You have to be extremely<br />

organized, especially if you<br />

are doing concerts with other<br />

instruments. If I’m playing<br />

my viola d’amore (12 or 14<br />

stringed cousin of the violin),<br />

or baroque violin, or even<br />

my medieval rebec, it’s not<br />

always feasible to be lugging<br />

around multiple instruments<br />

on airplanes unless<br />

you absolutely have to. It’s<br />

always such a pain in the<br />

butt to convince the flight<br />

attendants to let you bring<br />

them all on, so you don’t<br />

want to do it any more<br />

than absolutely necessary.<br />

Therefore, I also have to<br />

calculate how many days<br />

I’m actually home in my<br />

apartment to do some<br />

kinds of practicing. It<br />

becomes this big jigsaw<br />

puzzle, and the extra<br />

instruments become one<br />

more factor.

I believe it is important to maintain a variety of styles within my<br />

playing. I don’t mean odd styles like rock playing or early music, simply<br />

the core styles like high Baroque, Classical playing, late Romantic<br />

playing with all the expressive slides, virtuoso pyrotechnics. I find that<br />

I’m spending a month playing big romantic concertos, and during<br />

that whole month I don’t have anything that’s Mozart. The very careful<br />

cleanliness and refinement and sparkle that you need for a good<br />

Classical period sound requires a slightly different physical use of<br />

your left and right hands. I’m spending a whole month not doing that.<br />

Or maybe it’s the opposite. Maybe I’m playing a few dates of Mozart<br />

concertos and maybe a Shostakovich or some Bach and I’m not really<br />

doing any Romantic. I don’t want to lose that control over the timing<br />

of expressive slides when I’m playing music that doesn’t require it. I<br />

always try to think about the different kinds of playing that I want<br />

to make sure that I maintain in myself, and I compensate by playing<br />

some of that music even if it’s not scheduled. I might play the Amy<br />

Beach Romance just for fun or maybe something like the Meditation<br />

from Thais, just to make sure my expressive sound and slides are still<br />

at the ready. If I’m not playing any Bach for a while then I’ll add some<br />

Bach to the diet. We think about maintaining things like our left hand<br />

pizzicato or our upbow staccato scales every day, and sometimes forget<br />

to make sure that we’re maintaining all of our flavors of playing. As<br />

one of my favorite Scottish fiddlers Alasdair Fraser says, we need to<br />

be “multilingual” as instrumentalists. So it’s like speaking in different<br />

dialects, making sure that all of those languages are equally in<br />

good shape.<br />

One of things I find really useful is scales. So often, when we play a<br />

scale, we end up playing everything medium. Medium dynamics,<br />

mezzo something, medium speed, everything is medium. Of course,<br />

there are plenty of other things to think about when it comes to scales:<br />

intonation, fluid string crossings, invisible bow changes, equal bow<br />

distribution, clean shifts, left hand articulation. There are a million<br />

things to think about with a simple scale, but why not add tone color<br />

to that equation? It will make your scale a heck of a lot less boring, and<br />

it will get you in the right mood to play music. If you are going to work<br />

on the Sibelius concerto, maybe you should do a fortissimo scale, with<br />

a really wide, juicy vibrato. If you’re going to be doing some Debussy,<br />

do a flautando scale: a veiled sound, maybe sul tasto, (which is difficult<br />

to control), making a beautiful, floaty, French Impressionistic sound.<br />

If you’re going to be playing Brahms or Schumann, you want to make<br />

sure you don’t have any of that fuzz in there. You want to make sure<br />

you have a very thick sound, that your bow is really sinking into the<br />

string and that you have a nice concentrated vibrato.<br />

Focusing on bow weight (which is another way of saying dynamics)<br />

can create many different colors. A condensed slow and heavy bow<br />

as opposed to a fast sweeping bow can both end up being the same<br />

number of decibels, but they’re going to be different kinds of fortes.<br />

You have the freedom to manipulate dynamics, contact point, bow<br />

weight, bow speed and vibrato with every note! Just think of the<br />

variety you can achieve with vibrato alone. What width of vibrato?<br />

What speed of vibrato? If you think of all those different variables and<br />

combine them in all kinds of different ways, you’ve got infinite colors<br />

to paint with. Which scale are you going to do today? It might be a<br />

scale that relates to one of the important colors in the palate of the<br />

piece you’re working on. You’re actually warming yourself up for the<br />

proper Mozart sound by doing a very narrow vibrato with a very clean<br />

sound. Alternatively, you might decide to work on a Debussy scale<br />

because you haven’t played any impressionistic music in a while,<br />

and you want to make sure you don’t lose that nice sound you achieved<br />

while working on the Franck Sonata. Choosing what you’re going to<br />

do with your scales is based on filling in the gaps or enhancing what<br />

it is that you’re working on.<br />

You can also use repertoire you’ve already learned as a supplemental<br />

sort of etude. For instance, if you want to make sure you’re keeping<br />

your left hand pizzicato shored up you might grab some Sevcik. If you<br />

want to make sure you’re keeping your expressive slides solid, you<br />

probably want to grab out the character piece of your choice, maybe<br />

some schmaltzy Kreisler piece.<br />

Thinking about your practice session before you actually do it is<br />

critical. It’s equally important to be thinking about the practicing that<br />

goes in before you actually pick up the instrument and start addressing<br />

physics. Once you got the instrument in your hand, you’re being<br />

distracted by what’s happening. At that point, you ought to be paying<br />

total attention to noticing what you’re doing and relating that to what<br />

you intend to do. While you’re doing it is not the time to be figuring<br />

out what you intend to do. If you’re focusing on what’s happening, and<br />

you haven’t thought through your intentions carefully, you’re unlikely<br />

to have success either.<br />

From the macro to the micro<br />

The large picture involves planning the repertoire you need to prepare,<br />

the dates you need to prepare it, and working backwards to schedule<br />

your practicing today, tomorrow, and every day until the performances<br />

coming up. It’s a jigsaw puzzle for any musician, but you can’t get<br />

started without it. If you don’t have public concerts full time, the same<br />

thing can apply to your studies. Substituting whole concerts with<br />

youth orchestra music, chamber music, and perhaps a concerto for<br />

a competition, a sonata your teacher wants you to learn - you have<br />

a bunch of stuff on your plate, just a slightly different mix. You can<br />

assign priorities and deadlines to all those things. At this point you<br />

will know what you are practicing on any given day. If you just jump<br />

into your practice thinking “I’m going to start with the first thing I’m<br />

inspired to practice,” you run the risk of wasting the time you have<br />

to practice. It’s not realistic to expect an endless supply of 8 hour days<br />

where you can randomly choose what to practice. Most of us have to<br />

carve out time from a busy schedule, and it happens in small chunks.<br />

Map out the pieces you have ahead of you, the time you’ll need to<br />

spend on them based on difficulty or familiarity, and the time you<br />

have left before the concert and you’ll avoid panicking and trying<br />

to cram in time right before the performance. Once you’ve done this,<br />

you’ll have a rough practicing plan.<br />

It’s useful to put your practicing in order for the day as well. If you<br />

are looking to do 20 minutes of practicing fingered octaves, you will<br />

want to plan intelligently for that. You probably shouldn’t do those<br />

twenty minutes in a row because you don’t want to risk tendonitis. In<br />

that case, you need to know that you’re going to do 10 minutes now<br />

and the rest an hour later, with other practicing in between. You need<br />

to plan that out so you don’t get to the last twenty minutes of your<br />

practicing and realize you have to fit that in at the end! You can plan<br />

out whether you are going to do some technical work first and then<br />

artistic work, or start out with interpretation and then do rote work<br />

out of Schriadieck later. There are no right answers, it’s up to your<br />

own individual personality and how your focus tends to flow. A lot of<br />

it is experimentation, getting to know yourself - not just your artistic<br />

personality but your learning personality, who you are as a practicer.<br />

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST 19

You can become ever more expert at planning your practice sessions,<br />

to make the most effective possible use of your time.<br />

Take your plan down to the next level, after determining that you<br />

will spend 30 minutes on the first page of your concerto. Are you just<br />

going to play it over and over for half an hour? Are you going to jump<br />

in starting at the first note and then stopping if you hear something<br />

you want to fix? That is probably not the most useful way to go about<br />

it. You have to decide on the goals for your time. Maybe spend the first<br />

ten minutes drilling intonation: no vibrato, slowly, listen to every note,<br />

make sure it’s clean and in tune, that the rhythm is good. Then add<br />

the vibrato back, and you can think about phrasing and tone. Don’t let<br />

loose and play it with complete passion because you will distract yourself<br />

from making sure that everything is exactly the way you wanted.<br />

You need some emotion because the choice of vibrato stems from the<br />

choice of the phrasing, but you shouldn’t just completely lose yourself<br />

in the music. It’s vital to maintain the level of detail that you want in<br />

the performance, down to the specific quality of vibrato on each note,<br />

and the way those notes connect to one another. Your vibrato doesn’t<br />

necessarily obey your feelings until you train it to do so. You have to<br />

be absolutely, consciously aware of your all the different things that<br />

create the ebb and flow of phrases, and when you think about how<br />

many things that includes, you start to see the task at hand.<br />

A vital component of the process is to practice performing, which is<br />

almost the opposite of the slow and careful practicing. Whereas in<br />

slow and careful practicing you’re supposed to stop every time you<br />

hear something less than ideal, performing practice is about playing<br />

to the end of the piece. Listening for how you can improve, stopping<br />

to fix and work on things - that’s how you want to be practicing most<br />

of the time. Performance and practice have different purposes, and<br />

you need to have a different attitude to achieve them. Performance<br />

is about being positive and engaging the audience, almost the<br />

opposite mentality to the highly critical practice approach. You have<br />

to embrace the way your playing sounds now, even if you think in<br />

the back of your mind that you want to get better. Enjoy what you’re<br />

doing in the moment so you can convey it to the audience. Being an<br />

excellent practicer can make for bad performances, especially if you<br />

are transmitting your self-criticism through your playing. You need to<br />

do both, the perfectionistic, every-detail practicing, and the energetic<br />

and free performing.<br />

On a basic level, when you practice performing, don’t let yourself stop<br />

for anything. If you completely miss a shift, keep going. If you have<br />

a memory slip, barrel on through! Get used to that feeling of playing<br />

from beginning to end no matter what. Ignore the notes that have<br />

gone by because they are in the past. You should only think about<br />

what you’re doing at the moment and what’s coming up - the present<br />

and future.<br />

It’s simple enough to record yourself and listen back to catalogue all<br />

the things you want to work on. The performance playthrough has to<br />

be done with utmost expression and flair, making sure you’re putting<br />

on a good show and expressing the music as much as you can. When<br />

you listen back, it’s equally important to catalogue what you did well<br />

and what wasn’t so satisfactory. If something did go well, you want<br />

to recognize that you liked it so you can figure out how to repeat it.<br />

It’s not to compliment yourself, it’s to improve the bad and embrace<br />

the good.<br />

Plan out your practice sessions with careful slow practice and specific<br />

goals in mind. Focusing on one thing at a time may result in a mistake<br />

creeping in, but it allows you to try and completely fix one issue instead<br />

of being overwhelmed by all of them. Later in the development of a<br />

piece, you can start to put all the separate parts together, and zigzag<br />

your focus between different components of your technique and the<br />

music. Trying to put all this in action in the time you have to practice<br />

just won’t cut it.<br />

When I ask myself what I do for a living, my answer is that I am a<br />

concert violinist, I get up on stage and play concerts on my violin.<br />

When you get up there for that concerto you’re on stage for a half<br />

hour. Maybe 35 minutes if you play an encore. That 35 minutes pales<br />

in comparison to the 35 hours of practicing that concerto before I ever<br />

showed up in town to rehearse it. So really, I’m a professional practicer.<br />

That’s what I do for a living. If you want to become a professional<br />

performer, you have to train to be a professional practicer too. It is<br />

very useful to go through the trouble of writing your practice down.<br />

I have yet to see a great app that would help you to organize your<br />

practicing, but I hope one is on the way. Write it all down and have<br />

your practice plan sitting in front of you. It’s not necessary to follow<br />

it blindly. One part of your plan might take more time, and another<br />

less - don’t practice something 10 minutes because you wrote down<br />

10 minutes. Write down in one column what you plan to do, and in<br />

the next column write what you actually did, trying to stick to your<br />

plan. As you go along, month after month, your plans will become<br />

ever more experienced. What you planned to do and what you actually<br />

do will get closer and closer together. After many many months of<br />

doing this you’ll be able to do it in your head. That notebook is your<br />

friend for at least a year as you’re getting used to this way of practicing.<br />

So much of practicing is physical, whether it’s making sure your fingers<br />

are falling in the exact right spots, or trying to make the phrasing<br />

happen with bow speed and bow placement. We spend much of our<br />

practice time being athletes.<br />

We have to practice being stage performers. Sometimes I would do<br />

a whole visualization thing. I would start in my bedroom, and that<br />

would be my backstage warm up room. There are elements of<br />

performance you want to have figured out before the performance,<br />

such as what to play in that 5 minutes backstage before you go out to<br />

perform. If you try to decide on the spot, you could waste 3 of those<br />

minutes figuring it out! For me that time involves some slow scales<br />

and then turning on the headphones to some loud AC/DC. This allows<br />

me to feel physically in control but to find a way to build up my energy<br />

right before the show. I don’t do that anymore, necessarily, especially<br />

with children. Figure out what backstage routine works for you,<br />

because you’re not going to have enough concerts to figure it out in<br />

the actual concert, and it’s not the time for experimentation. Visualize<br />

in your own apartment. Have a fake warm-up before your fake concert<br />

and know what you like to do. I used to walk out into my living room<br />

and have a couple of stuffed animals on the couch, to know the direction<br />

of the audience. I would shake the hand of the fake pianist or conductor,<br />

tune and play my piece, smile, bow, and walk back off stage. If you<br />

never practice these things, you will feel nervous for them. We stop<br />

bowing after Suzuki, in most cases. Any opportunity you have is one<br />

more chance to prepare for the big show. You’re creating a familiar<br />

physiological feeling.<br />

We are often preparing music that we don’t know well, spending whole<br />

days playing pieces we aren’t yet familiar with. Find a favorite piece,<br />

something you can already play well and polish this piece, maintain it.<br />

20 SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST

SUMMER 2014 NEXT LEVEL VIOLINIST 21

With limited practice, you can’t spend much<br />

time on it, but every day play something on<br />

your instrument that you play well. Even if it’s<br />

a page of last year’s easy concerto, just play it<br />

so that you can play something on your violin<br />

that sounds and feels good. Play a page of<br />

the Mendelssohn while you’re still struggling<br />

with the Tchaikovsky. You don’t want to do<br />

only the Tchaikovsky slowly plus etudes and<br />

scales all day. That could be demotivating and<br />

it’s not necessarily healthy for yourself as an<br />

artist, since you can’t let loose.<br />

The shape of a musical life<br />

I give masterclasses virtually every week and<br />

I used to have a studio in the early nineties.<br />

I miss it, seeing the pleasure of week to week<br />

progress with a student and the pleasure of<br />

the relationships that you build with those<br />

people. A teacher is an immensely important<br />

person in a music student’s life. It’s incredible<br />

when students grow up to become friends<br />

and colleagues. I think doing teaching right<br />

involves being there every 7 days for lessons,<br />

putting in extra time before competitions, and<br />

really giving it your all. There’s a number of<br />

other things I’ve chosen to do right now. I’ve<br />

been doing a lot of publishing. Carl Fischer<br />

and I are collaborating on a series of all of<br />

the great etude books re-edited; the last time<br />

some of them were edited was about a hundred<br />

years ago. They are being revised with modern<br />

fingerings and bowings and companion<br />

DVD’s or CDs. In case of the first ones that<br />

have come out, the Wohlfahrt etudes, the<br />