AA 2.indd - Colnaghi

AA 2.indd - Colnaghi

AA 2.indd - Colnaghi

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

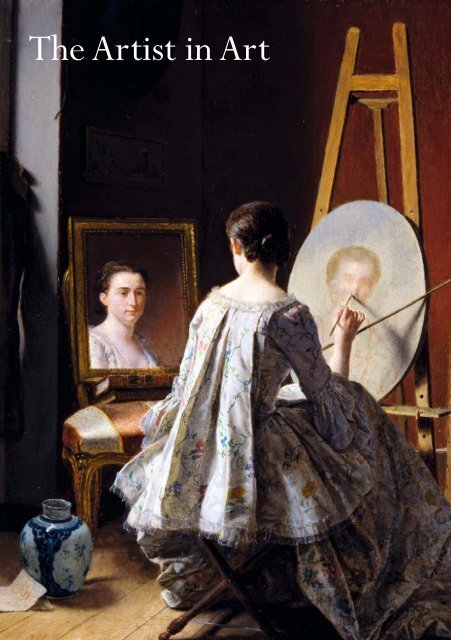

The Artist in Art

Preface<br />

This exhibition would not have been possible<br />

without the help and collaboration of a<br />

number of people who have contributed<br />

generously in terms of loans or their expertise.<br />

Above all we would like to thank our partner<br />

in this exhibition, Emanuel von Baeyer. We<br />

would also like to thank Sir Jack Baer, Patrick<br />

Bourne and the Fine Art Society, Green &<br />

Stone of Chelsea, Bob Haboldt, Philip Mould,<br />

Bendor Grosvenor, Rupert Maas, Edmondo<br />

di Robilant, Guy Sainty, Guy Wildenstein and<br />

Rafael Valls. Finally we would like to thank<br />

Sarah Gallagher, Lucia Prosino and Jeremy<br />

Howard, who organised the exhibition and<br />

wrote the catalogue.<br />

Konrad Bernheimer and Katrin Bellinger,<br />

November, 2007.<br />

Front Cover:<br />

JEAN ALPHONSE ROEHN<br />

(Paris 1799 –1864 Paris)<br />

Portrait of an Artist painting her Self-Portrait<br />

Cat.50

The Artist in Art<br />

26th November 2007 – 1st February 2008<br />

COLNAGHI<br />

In association with Emanuel von Baeyer

Introduction<br />

The present exhibition explores the varying<br />

ways in which artists have chosen to depict<br />

themselves and the making of their art. As<br />

such it embraces portraits and self-portraits,<br />

studio interiors, still lifes of artists’ materials<br />

and studies of models; it takes in academies,<br />

themselves outgrowths of studios. It also<br />

includes the collectors, patrons and dealers<br />

who were to be found in the studios and<br />

at academy views and in the museums,<br />

which, from the early nineteenth century,<br />

played an increasingly important role in the<br />

consumption of art.<br />

The delineation of the artist is seen in its<br />

purest form in the self-portrait. Here the<br />

preoccupations of the artist can be honestly<br />

examined, because he has no sitter to flatter<br />

or patron to please. The history of the selfportrait<br />

really begins with Dürer. Prior to his<br />

time, there are a few direct self-portraits and<br />

artists tended to appear in the guise of St Luke,<br />

or as bystanders. Sometimes, as in Van Eyck’s<br />

famous reflected self-portrait in the convex<br />

mirror of The Arnolfini Portrait (National<br />

Gallery, London), they introduced themselves<br />

obliquely into their pictures with the same<br />

stealth that Hitchcock used to appear in his<br />

own films, a conceit that evidently appealed<br />

three centuries later to Fragonard’s sister-in-law<br />

Marguerite Gerard (Plates 1 & 2) who painted<br />

her reflection in a ball. But these images of<br />

artists were essentially self-effacing, perhaps<br />

reflecting their relatively lowly standing.<br />

The improved status of artists in the High<br />

Renaissance is reflected in the growth in the<br />

number of self-portraits, a trend given further<br />

impetus by the tradition in Rome in the later<br />

sixteenth century of presenting self-portraits<br />

to the newly founded Academy of St Luke.<br />

Some artists, such as Van Dyck, preferred<br />

not to present themselves primarily as artists,<br />

but as connoisseurs or courtiers: basking<br />

symbolically in the warmth of royal patronage<br />

in the case of his famous Self-Portrait with a<br />

Sunfl ower (Royal Collection, England), or as<br />

Paris, judge of beauty in his self-portrait in the<br />

Wallace Collection. By contrast, other selfportraits<br />

display a keen interest in the processes<br />

of making art and very little concern to project<br />

an elevated image. In his wild and almost<br />

caricatural self-portrait drawing (illustrated<br />

back cover) the young Toulouse-Lautrec, his<br />

stunted body emphasised by the large brushes<br />

he wields, shows himself in the act of painting<br />

and is quite unconcerned to project the sort<br />

of gentlemanly image conventional in the<br />

eighteenth century. By contrast the flower<br />

painter Spaendonck (Plate 6), lays down his<br />

crayon holder to welcome the spectator from<br />

a Louis XVI chair more redolent of the salon<br />

than the studio. In Tischbein’s remarkable<br />

self-portrait in masquerade costume (Plate<br />

4), there are no indications of his professional<br />

calling and the only allusion to the art of<br />

painting is an indirect one: the mask, a<br />

symbol associated with allegorical depictions

Plate 1<br />

JEAN HONORÉ FRAGONARD<br />

(Grasse 1732 – 1806 Paris ) and<br />

MARGUERITE GÉRARD<br />

(Grasse 1761 – 1837 Paris)<br />

Le Chat Angora<br />

Cat.24<br />

Plate 2<br />

JEAN HONORÉ FRAGONARD<br />

(Grasse 1732 – 1806 Paris) and<br />

MARGUERITE GÉRARD<br />

(Grasse 1761 – 1837 Paris)<br />

Le Chat Angora<br />

DETAIL<br />

of painting, which is worn round the neck<br />

of Pittura in Ripa’s Iconologia to show the<br />

connection between painting and imitation.<br />

Here, though, the artist, like an actor, removes<br />

rather than dons his mask and doffs his hat<br />

to his audience, revealing his “real” self,<br />

presented, though, through the illusion of art.<br />

This is self-portraiture as performance rather<br />

than introspection. Conversely, Pechstein’s<br />

self-portrait drawn in 1917 (Cat.47), a<br />

profound and melancholic study of a young<br />

man who had just returned from the trenches,<br />

shows self-portraiture’s capacity to reveal the<br />

artist’s soul; and Spare’s weird Self-Portrait<br />

with Animal Forms (Cat.58), its ability to<br />

explore the darker areas of the psyche.<br />

Painting self-portraits before the invention<br />

of photography inevitably involved the use<br />

of a mirror, as one can see in the charming<br />

studio interior by Roehn (illustrated front<br />

cover) and the canvas effectively captures<br />

the image seen in the mirror. The process of<br />

translating the mirror image onto the canvas<br />

means that the eyes of artists in self-portraits<br />

look out at us with peculiar intensity and are<br />

separately focused, an effect observable in the<br />

Tischbein (Plate 4) and in Boetius’s engraving<br />

after Mengs’s splendidly assured self-portrait<br />

(Plate 3). This can also lead to an intriguing<br />

interplay between canvas and mirror and the<br />

possibilities of multiple viewpoints. In the<br />

Roehn, we see simultaneously the artist’s face<br />

and the back of her head, her reflected and<br />

painted images. The mirror also provides<br />

opportunities for the artist to explore facial<br />

expressions, as captured by the engraver

Kerrich (Cat.36), which was in line with<br />

academic theories about the training of artists,<br />

particularly in France, where the painting of<br />

têtes d’expression became an essential part of<br />

the curriculum.<br />

The influence of the academy can be felt in<br />

Blanchet’s portrait of Panini (Plate 5). This<br />

stresses the more gentlemanly and intellectual<br />

notion of the artist, which grew out of the<br />

Renaissance idea that painting was a liberal<br />

rather than a mechanical art. Panini taught<br />

perspective at the French academy in Rome<br />

where he was accorded the rare honour (for a<br />

non-Frenchman) of membership. This may<br />

explain why, although a canvas is shown in the<br />

background, he holds a drawing instrument<br />

rather than a brush, and clutches a portfolio of<br />

sketches, emphasizing the primacy of disegno,<br />

the chalk being used to make the first marks<br />

on the canvas. Whereas the Panini portrait<br />

plays down the craft aspects of painting, Le<br />

Carpentier’s portrait of his friend the engraver<br />

Gelée (Plate 10) revels in the processes of<br />

engraving and the tools of the trade: the<br />

magnifying glass, the burin and the copper<br />

plate, though the head turned upwards not<br />

only reflects the process of copying a design, but<br />

also suggests sublimity. Such elevated images<br />

of the artist are a world away from Decamps’<br />

caricatural depiction of the artist as a monkey<br />

(Cat.17), which draws upon a tradition going<br />

back to Teniers, but also perhaps refers to<br />

the notion of artists as the apes of nature, or<br />

Rowlandson’s Manufacturers of Old Masters at<br />

Work (Plate 9), which satirises a particularly<br />

dubious aspect of artistic practice: the faking<br />

of old masters. Rowlandson’s caricature takes<br />

its cue from Hogarth’s earlier satirical assault<br />

on what he called “the Dark Masters” in the<br />

engraving, Time Smoking a Picture, though<br />

it is typical of Rowlandson’s quirky humour<br />

that the pipe that the artist smokes to darken<br />

the picture also cures some hams suspended<br />

from the rafters of the studio. Different again<br />

from the polished portraits of eighteenthcentury<br />

painters is Isidore Pils’ watercolour<br />

of a sculptor at work (Plate 8) where what is<br />

stressed is the physical effort involved in the<br />

production of sculpture. This calls to mind<br />

Leonardo’s observation that, while the painter<br />

sits at ease in his chair in his fine clothes, the<br />

sculptor labours amidst the dust and noise of<br />

his workshop and, in the Pils watercolour, has<br />

to climb up to work on the block.<br />

Paintings of studio interiors can be seen as<br />

extensions of portraiture, which also touch<br />

upon still-life painting. Curiously enough<br />

the two most famous examples of this genre,<br />

Velázquez’s Las Meninas and Vermeer’s A<br />

Painter at Work, would not have been nearly<br />

as familiar to most of the artists in the present<br />

exhibition as they are to us, because Vermeer<br />

was largely forgotten until revived by Thoré<br />

-Bürger in the 1860s and Velázquez’s greatness<br />

was only realised gradually as part of a general<br />

revival of interest in Spanish painting in the<br />

1830s and 1840s. The artists of the past,<br />

whose studios were imaginatively recreated<br />

in the nineteenth century, tended to be the<br />

giants of the Italian Renaissance. The emphasis<br />

was upon episodes in their lives, Leonardo<br />

expiring in the arms of Francois I or Charles V<br />

stooping to pick up Titian’s paint-brush, which<br />

stressed the wordly success of artists and the<br />

rich and powerful paying homage to genius.<br />

Artists also emphasized the polarities of their<br />

temperaments as in Horace Vernet’s Raphael<br />

at the Vatican (Cats.65 & 66), where Raphael<br />

and Michelangelo are brought together, like<br />

rivals in the boxing ring in the presence of<br />

Julius II. Many of the episodes depicted, such<br />

as in Evariste Fragonard’s painting of a quarrel<br />

between Aretino and Tintoretto in the artist’s<br />

studio (Cat.23) probably never happened,<br />

but they tell us a lot about how artists saw<br />

themselves, mirrored in the lives of the artists

of the past, and about contemporary artistic<br />

movements. It was appropriately the romantic<br />

painter Delacroix who executed one of the few<br />

“melancholic” depictions of a historical artist’s<br />

studio, showing Michelangelo brooding<br />

among his statues (in the Museé Fabre,<br />

Montpellier), whereas Ingres’ Raphael and<br />

the Fornarina (Fogg Art Museum, Harvard<br />

University) is a homage paid by the archpriest<br />

of classicism to his much more sociable and<br />

attractive artistic idol. Ingres’ painting also<br />

suggests the possibilities of the studio as a site<br />

of romantic encounters between male artists<br />

and their models, knowingly alluded to by<br />

Baudouin in his prurient Shy Model (Cat.4).<br />

Such pictures, of course, promote an<br />

essentially masculine view of artistic practice.<br />

But, increasingly from the late eighteenth<br />

century onwards, women were playing a role<br />

which is reflected in the growing number of<br />

studio interiors in which they feature. During<br />

the late eighteenth century, women artists<br />

such as Angelica Kauffmann and Elizabeth<br />

Vigée Lebrun enjoyed an unparalleled degree<br />

of esteem, which may explain the relative<br />

confidence of the images of female artists<br />

at this period. But on the whole the female<br />

artists who inhabit the studio interiors of the<br />

nineteenth century are comparatively demure<br />

and inward-turning: the artists in Roehn’s and<br />

Mary Churchill’s studio interiors (illustrated<br />

front cover, Cat.50 & Cat.14) turn their backs<br />

to us while Catherine Engleheart’s female<br />

artist (Cat.21) is rapt in contemplation. But<br />

compelling though these studio portraits<br />

are, it is the uninhabited spaces which are<br />

in some ways the most intriguing, precisely<br />

because we feel the absence of the artist and<br />

are encouraged to build up a picture of his<br />

interests and his artistic personality from the<br />

clues left strewn around the studio, such as the<br />

red shawl in Armand Laureys’ Studio Interior<br />

(Cat.39) or, in the case of the painting by the<br />

Neo-Impressionist Maximilian Luce (Cat.43),<br />

his bedroom. Up until the mid-nineteenth<br />

century art was made in the studio, but with<br />

the growth of plein-air painting we find<br />

German artists such as Metz and Gurlitt<br />

setting up their portable easels, paintboxes<br />

and parasols in front of Nature at Ariccia<br />

(Cat.30) at exactly the same moment, in the<br />

1840s, that the Barbizon painters were paving<br />

the way for Impressionism in the forest of<br />

Fontainebleau.<br />

The tradition of collectors and patrons and<br />

friends visiting the artist’s studio, charmingly<br />

portrayed by Hutin (Cat.33) is one that<br />

stretches back to Alexander and Apelles, and,<br />

increasingly from the eighteenth century<br />

onwards, the dealer figures in these interiors,<br />

reflecting his increasing importance as<br />

artistic middleman, promoter and patron.<br />

Printmaking underpinned the growth of<br />

the contemporary art market in the late<br />

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which<br />

is why the dealer Paul <strong>Colnaghi</strong> is portrayed<br />

with a portfolio of prints on his knee (Cat.64),<br />

and by 1871 the Art Journal was reporting<br />

that “to [the dealer] has been due, to a great<br />

extent the immense increase in prices of<br />

modern pictures”. One of the major players<br />

in the 1870s was Sir Coutts Lindsay, seen here<br />

(Cat.42) in his role as an artist, but who is<br />

best known as the proprietor of the Grosvenor<br />

Gallery. It was his championship of Whistler,<br />

the “coxcomb” that Ruskin accused of “flinging<br />

a pot of paint in the face of the public”, that<br />

was an important contributing factor to the<br />

victory of the avant-garde in late Victorian<br />

England. In the meantime, though, artists<br />

in late nineteenth-century Munich (Plate 14)<br />

continued to set up their easels in the museums<br />

and draw inspiration from the “dark masters”<br />

satirised by Hogarth and Rowlandson.<br />

Jeremy Howard

Portraits and Self-Portraits<br />

This section explores how artists presented<br />

themselves or were seen by other artists.<br />

These portraits range from the official images<br />

designed to elevate the status of artists,<br />

such as Blanchet’s Portrait of Panini (Plate<br />

5) to the informal friendship portraits, or<br />

Freundschaftsbilder, particularly popular<br />

with German artists in the early nineteenth<br />

century (Cat.28). They range from the proud<br />

self-portrait of Mengs (Plate 3), who, by the<br />

time of Boetius’s engraving of 1770, was one<br />

of the greatest artistic celebrities in Europe,<br />

through Spaendonck’s urbane drawing of<br />

himself seated in a chair (Plate 6), to the<br />

slightly more diffident portrait of Carle<br />

Vernet, clutching a portfolio of drawings<br />

and turning round towards the viewer by the<br />

female artist Catherine Lusurier (Plate 7), a<br />

pupil of Drouais. Interestingly, none of the<br />

artists illustrated here are shown holding a<br />

paint brush.<br />

Plate 3<br />

CHRISTIAN FRIEDRICH BOETIUS<br />

(Leipzig 1706 – 1778 Dresden), after<br />

ANTON RAPHAEL MENGS<br />

(Czech Republic 1728 – 1779 Rome)<br />

Self-Portrait of the Artist Anton Raphael Mengs<br />

Cat.9<br />

Plate 4<br />

JOHANN HEINRICH TISCHBEIN<br />

(Haina 1722 – 1789 Kasel)<br />

Self-Portrait in Venetian Masquerade Costume<br />

Cat.61<br />

Opposite:<br />

Plate 5<br />

LOUIS-GABRIEL BLANCHET<br />

(Paris 1705 – 1772 Rome)<br />

Portrait of Giovanni Paolo Panini<br />

Cat.7

Plate 6<br />

GERARD VAN SPAENDONCK<br />

(Tilburg 1746 – 1822 Paris )<br />

Self Portrait seated at a Table turned to the Right<br />

Cat.57

Plate 7<br />

CATHERINE LUSURIER<br />

(Paris 1752 – 1781 Paris)<br />

Portrait of the Artist Carle Vernet<br />

Cat.44

Artists at Work<br />

Many of the portraits of artists in the first<br />

section give little hint of their professional<br />

calling, beyond the fixed stare, separately<br />

focussed eyes and turn of the head peculiar to<br />

self-portraits (Plates 3, 4 & 6). This section,<br />

however, explores artists at work, through<br />

portraits and studio interiors in which the<br />

emphasis is on the artistic processes, materials<br />

and the tools of the trade. They range from<br />

Le Carpentier’s affectionate portrayal of his<br />

friend Gelée engraving a copper plate (Plate<br />

10), to Isidore Pils’s watercolour evoking the<br />

dust and physical exertion of the sculptor’s<br />

studio (Plate 8) to Rowlandson’s caricature<br />

of an artist faking old masters (Plate 9) and<br />

smoking a pipe as he does so to darken the<br />

canvas.<br />

Plate 8<br />

ISIDORE-ALEXANDRE-AUGUSTIN PILS<br />

(Paris 1813 – 1875 Douarnenez)<br />

A Sculptor in his Studio<br />

Cat.48<br />

Plate 9<br />

THOMAS ROWLANDSON<br />

(London 1756 – 1827 London)<br />

Manufacturers of Old Masters at Work<br />

Cat.52

Plate 10<br />

PAUL CLAUDE MICHEL LE CARPENTIER<br />

(Rouen 1787 – 1877 Paris)<br />

Portrait of Antoine-Francois Gelée (1796 – 1860)<br />

Cat.11

Academies of Art<br />

Academies, which first evolved in Italy in the<br />

sixteenth century, provided three essential<br />

functions which helped to raise the status<br />

and improve the conditions of contemporary<br />

artists: one was education, another was the<br />

prestige and professional recognition and<br />

the third was a mechanism for selling their<br />

work through exhibitions. Essential to any<br />

access to the “highest” branch of history<br />

painting, was the opportunity to study from<br />

the live naked model, seen here in the Comte<br />

de Paroy’s etching of a drawing academy<br />

(Plate 11). Women artists were under a huge<br />

disadvantage, in being excluded at this period<br />

from life classes for reasons of propriety, which<br />

explains why Angelica Kauffmann and Mary<br />

Moser, the two female founder members,<br />

were not allowed to be present in Zoffany’s<br />

Famous painting of the Life School, The<br />

Academicians of the Royal Academy (Cat.20),<br />

but were represented, rather coyly through<br />

their portraits hung on the wall.<br />

Plate 11<br />

JEAN-PHILIPPE GUY LE GENTIL, COMTE DE<br />

PAROY<br />

(Paris 1750 – 1824), after<br />

FRANCOIS GUILLAUME MENAGEOT<br />

(London 1744 – 1816 Paris)<br />

The Drawing Academy<br />

Cat.31<br />

Allegories of Art<br />

An essential idea behind the growth of<br />

academies was the notion that painting<br />

was not just a mechanical craft as had been<br />

considered to be the case in the Middle<br />

Ages, but was a liberal art, which deserved<br />

to be given equal status with poetry. Artists<br />

were encouraged to draw inspiration from<br />

poetry, and inverting Horace’s notion of<br />

ut pictura poesis (as a painting, so should a<br />

poem be), to paint pictures which were the<br />

visual equivalents of poems, but, so artists<br />

argued, superior in being more lifelike. This<br />

explains why in Toorenvliet’s An Allegory of<br />

Painting (Plate 12), the female personification<br />

of painting draws inspiration from a book,<br />

while other attributes such as a laurel branch<br />

and a skull allude to art’s capacity to promote<br />

fame and ensure immortality.<br />

Plate 12<br />

JACOB VAN TOORENVLIET<br />

(Leiden c. 1635/41 – 1719 Leiden)<br />

An Allegory of Painting<br />

Cat.63

Connoisseurs and Art Lovers<br />

Some of the earliest depictions of artists’<br />

studios show visits from patrons, friends and<br />

art lovers. This was a tradition that went back<br />

to the story of Alexander visiting the studio of<br />

Apelles, a subject which was painted by artists<br />

such as the seventeenth-century Dutch master<br />

Van Haecht, whose version of the subject,<br />

dated in 1628 and now in the Mauritshuis,<br />

was based, in part, on the interior of Rubens’<br />

studio. Rubens as the modern Apelles was also<br />

shown in his studio receiving a visit from the<br />

Archduke Albert. The eagerness with which<br />

male connoisseurs scrutinised erotic pictures<br />

had been satirised by Watteau in L’Enseigne<br />

de Gersaint, which doubtless inspired Hutin’s<br />

witty etching of four connoisseurs examining<br />

a painting of Leda and the Swan (Plate 13).<br />

Vetter’s painting of a largely female group of<br />

art lovers in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich<br />

(Plate 14), while an artist copies a painting<br />

by Rubens, and Adolphe Leleux’s Interior of<br />

the Louvre (Cat.40) show more respectable<br />

aspects of connoisseurship.<br />

Plate 13<br />

PIERRE HUTIN<br />

(Paris c.1720 – 1763 Moscow)<br />

Four Friends in an Artist’s Studio<br />

Cat.33

Plate 14<br />

CHARLES FRIEDRICH ALFRED VETTER<br />

(Kahlstadt 1858 – 1936 Kahlstadt)<br />

A Visit to the Munich Pinakothek<br />

Cat.67

List of Works<br />

1.<br />

CHARLES ARNOUD (Paris, active 1864 – 1880)<br />

Subjects for a Still-Life<br />

Signed and dated lower left: Arnoud 77<br />

Oil on panel<br />

17 x 12 ¼ in. (43 x 31cm.)<br />

2.<br />

JEAN AUBERT (Paris, active Eighteenth Century)<br />

Portrait of the Artist Claude Gillot<br />

Engraving<br />

19 ⅜ x 15 ⅜ in. (48.5 x 38.5 cm.)<br />

3.<br />

JEAN BAPTISTE BERNARD COCLERS<br />

(called LOUIS BERNARD) (Liège 1741 – 1817 Liège)<br />

Portrait of the Artist Jacob Jansons<br />

Inscribed in pencil: no.2<br />

Etching<br />

6 ½ x 5 ¼ in. (16.2 x 13.1 cm.)<br />

4.<br />

PIERRE ANTOINE BAUDOUIN<br />

(French 1723 – 1779)<br />

The Shy Model<br />

Signed lower left on table: B<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

15 ½ x 12 ¾ in. (39.4 x 32.4 cm.)<br />

5.<br />

JEAN BERAUD<br />

(St. Petersburg 1849 – 1936 Paris)<br />

A Portrait of the Artist in his Studio<br />

Signed and dated lower right: Jean Beraud 1876<br />

Oil on board<br />

6 ½ x 3 ½ in. (16 x 9 cm.)<br />

6.<br />

CORNELIS VAN DEN BERG<br />

(Harlem 1699 – 1764 Harlem)<br />

Self-Portrait<br />

Inscribed: Door hem zelfs geteerskend en ge-etst. 1759<br />

Etching<br />

5 ¼ x 2 5⁄6 in. (13 x 6.6 cm.)<br />

7.<br />

LOUIS-GABRIEL BLANCHET<br />

(Paris 1705 – 1772 Rome)<br />

Portrait of Giovanni Paolo Panini<br />

Indistinctly signed and dated on the book lower left:<br />

L G Blanchet It / 1736<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

38 x 30 in. (96.5 x 76 cm.)<br />

With tracing of an old inscription on the back of the<br />

original canvas: ‘Paolo Panini, peintre d’ Architecture/<br />

Orig. [le] Peint par G. Blanchet a Rome’<br />

[Plate 5]<br />

8.<br />

FREDERICK BLOEMAERT,<br />

(Utrecht 1614/17 – 1690 Utrecht), after<br />

ABRAHAM BLOEMAERT<br />

(Gorinchen 1566 – 1651 Utrecht)<br />

The Student Draughtsman: Frontispiece to Konstryk<br />

Tekenboek (Artistic Drawing Book)<br />

Inscribed: Abrahamus Bloemaert inventor. Fredericus<br />

Bloemaert Filius fecit et exe<br />

Chiaroscuro woodcut with etching<br />

12 ⅜ x 9 in. (30.8 x 22.5 cm.)<br />

9.<br />

CHRISTIAN FRIEDRICH BOETIUS<br />

(Leipzig 1706 – 1778 Dresden), after<br />

ANTON RAPHAEL MENGS<br />

(Czech Republic 1728 – 1779 Rome)<br />

Self-Portrait of the Artist Anton Raphael Mengs<br />

Stipple engraving on pink paper<br />

9 ⅞ x 7 ⅝ in. (24.6 x 19 cm.)<br />

[Plate 3]<br />

10.<br />

ADRIEN DE BRAEKELEER<br />

(Antwerp 1818 – 1904 Antwerp)<br />

The Artist’s Studio<br />

Signed lower left: Adrien de Braekeleer<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

20 ½ x 25 ¾ in. (52.5 x 65.5 cm.)<br />

11.<br />

PAUL CLAUDE MICHEL LE CARPENTIER<br />

(Rouen 1787 – 1877 Paris)<br />

Portrait of Antoine-Francois Gelée (1796 – 1860)<br />

Signed, dated and inscribed lower right:<br />

Paul Carpentier p.x 1832 à son ami Gelée<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

30 ½ x 32 ¼ in. (100 x 82 cm.)<br />

[Plate 10]<br />

12.<br />

GUILLAUME-SULPICE CHEVALIER, called<br />

GAVARNI (Paris 1804 – 1866 Paris)<br />

An Allegory of Sculpture<br />

Lithograph on chine collé<br />

17 ¾ x 12 ⅜ in. (44.5 x 30.8 cm.)<br />

13.<br />

DANIEL NIKOLAS CHODOWIECKI<br />

(Gdansk 1726 – 1801 Berlin)<br />

The Painter’s Cabinet<br />

Etching<br />

7 ⅛ x 9 ⅛ in. (18 x 23 cm.)

14.<br />

MARY CHURCHILL<br />

(Active Late Nineteenth Century)<br />

Interior of the Studio with the Artist Painting a Landscape<br />

Signed and dated lower right: Mary Churchill 1887<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

20 ⅛ x 14 in. (51 x 35.5 cm.)<br />

15.<br />

ALBERT HENRY COLLINGS, RBA<br />

(Active Early Twentieth Century, London, died 1947)<br />

The Studio<br />

Oil on board<br />

11 ¼ x 10 ½ in. (28.7 x 26.7 cm.)<br />

16.<br />

ARNOLD CORRODI<br />

(Rome 1846 – 1874 Rome)<br />

Portrait of the Artist’s Father, Salomon Corrodi<br />

Signed lower right: A. Corrodi<br />

Pencil<br />

11 ¼ x 8 ⅜ in. (28.2 x 21 cm.)<br />

17.<br />

ALEXANDRE-GABRIEL DECAMPS<br />

(Paris 1803 – 1860 Fontainebleau)<br />

A Sketch of a Studio Interior with a Monkey Painter<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

12 ⅞ x 16 in. (32.5 x 40.5 cm.)<br />

18.<br />

LOYS HENRI DELTEIL<br />

(Paris 1869 – 1927 Paris)<br />

Woman Artist at an Easel<br />

Etching<br />

17 x 216⁄8 in. (43 x 54.2 cm.)<br />

19.<br />

JEAN-CLAUDE DUMONT<br />

(Lyon 1805 – 1874/75 Lyon)<br />

Still-Life with Artist Palette, Brushes and Ecorché<br />

Figure on a table<br />

Signed lower left: J-C Du…t<br />

Oil on board<br />

7 ¼ x 9 ½ in. (18.5 x 24 cm.)<br />

20.<br />

RICHARD EARLOM<br />

(London 1743 – 1822 London) after JOHAN<br />

ZOFFANY<br />

(Frankfurt 1733 – 1810 London)<br />

The Academicians of the Royal Academy<br />

Mezzotint, published 1733<br />

28 ¼ x 19 ⅞ in (70.63 x 49.7 cm.)<br />

21.<br />

CATHERINA CAROLINE CATHINKA<br />

ENGELHART<br />

(Copenhagen 1845 – 1926 Copenhagen)<br />

Lady at the Window in the Artist’s Studio<br />

Signed with monogram and dated lower left: EC 1843<br />

Oil on board<br />

30 ¼ x 21 in. (77 x 54 cm.)<br />

22.<br />

JOHN FAED, RA RSA<br />

(Burley Mill 1819 – 1902 Burley Mill)<br />

A Gentle Critic<br />

Signed and indistinctly dated lower right<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

18 ½ x 15 ½ in. (47 x 39.5 cm.)<br />

23.<br />

ALEXANDRE-EVARISTE FRAGONARD<br />

(Grasse 1780 – 1850 Paris)<br />

Aretino in the Studio of Tintoretto<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

16 ⅛ x 13 ½ in. (41 x 35.4 cm.)<br />

24.<br />

JEAN HONORÉ FRAGONARD<br />

(Grasse 1732 – Paris 1806) and<br />

MARGUERITE GÉRARD<br />

(Grasse 1761 – 1837 Paris)<br />

Le Chat Angora<br />

Oil on canvas, unlined<br />

25 ½ x 21 in. (65 x 53.5 cm.)<br />

[Plates 1 & 2]<br />

25.<br />

FRENCH SCHOOL<br />

(Late Nineteenth Century)<br />

Artist Painting at his Easel, the Venus de Milo in<br />

the background<br />

Black chalk on brown paper<br />

11 ¾ x 17 ¼ in. (29 x 44.5 cm.)<br />

26.<br />

FRENCH SCHOOL<br />

(Late Eighteenth Century)<br />

Lady Artist in her Studio<br />

Oil on panel<br />

9 ½ x 7 ½ in. (24 x 19 cm.)<br />

27.<br />

MARIA ELECTRINE VON FREYBERG<br />

(Strasburg 1797 – 1847 Munich)<br />

Portrait of a Seated Female Artist with a Pen<br />

Pencil<br />

9 ½ x 7 in. (23.7 x 17.6 cm.)

28.<br />

MAX FÜRST<br />

(Traunstein 1846 – 1917 Munich)<br />

Portrait of the Painter Nikolaus Gysis<br />

(1842-1901), bust-length<br />

Monogrammed and dated lower left: M.F. / 1865 and<br />

inscribed lower right: Studienkollege / N. Gysis / aus<br />

Griechenland<br />

Oil on paper laid down on artist’s board<br />

17 ⅞ x 15 ⅛ in. (45. 5 x 38.5 cm.)<br />

29.<br />

GERMAN SCHOOL<br />

(Second half of Nineteenth Century)<br />

View of the drawing Classroom in the Old Royal Saxony<br />

Arts and Craft School in Dresden<br />

Watercolour over pencil.<br />

6 ½ x 10 ⅞ in. (16.3 x 26.8 cm.)<br />

30.<br />

GERMAN SCHOOL<br />

(Nineteenth Century)<br />

The Painters Metz and Gurlitt working en Plein Air<br />

Inscribed and dated: Maler Metz und Maler Gurlitt,<br />

bei Ariccia 21 7 43<br />

Pencil on paper<br />

8 x 10 ½ in. (20.4 x 27cm.)<br />

31.<br />

JEAN-PHILIPPE GUY LE GENTIL,<br />

COMTE DE PAROY (Paris 1750 – 1824 Paris), after<br />

FRANÇOIS GUILLAUME MENAGEOT<br />

(London 1744 – 1816 Paris)<br />

The Drawing Academy<br />

Etching with roulette and aquatint<br />

10 ⅞ x 16 in. (27.2 x 39.9 cm.)<br />

[Plate 11]<br />

32.<br />

LAURENT GUYOT<br />

(Paris 1756 – 1808 Paris)<br />

The Painter Simon Mathurin Lantara in his Studio<br />

Etching with burin<br />

9 ¼ x 7 in. (23 x 17.4 cm.)<br />

33.<br />

PIERRE HUTIN<br />

(Paris c.1720 – 1763 Moscow)<br />

Four Friends in an Artist’s Studio<br />

Inscribed and dated: pierre. hutin sculp. 1754<br />

Etching<br />

5 ¾ x 3 ⅝ in. (14.3 x 9.1 cm.)<br />

[Plate 13]<br />

34.<br />

CHARLES KEENE<br />

(London 1823 – 1891 London)<br />

Artist in front of an Easel (verso)<br />

Portrait of a Boy Drawing (recto)<br />

Pencil<br />

5 ⅞ x 3 ⅞ in. (14.7 x 9.7 cm.)<br />

35.<br />

ALBERT VON KELLER<br />

(Gais 1844 – 1920 Munich)<br />

Study of Five Female Nudes<br />

Signed lower right: ALBERT. KELLER.<br />

Oil on artist’s board<br />

14 ⅜ x 9 ⅞ in. (36.5 x 25 cm.)<br />

36.<br />

THOMAS KERRICH<br />

(Norfolk 1748 – 1828 Norfolk)<br />

Self-Portrait with Four Different Expressions<br />

Pencil<br />

13 x 7 ⅞ in. (32.5 x 19.8 cm.)<br />

37.<br />

ALPHONSE DE LABROUE<br />

(Metz (?) 1792 – 1863 Metz)<br />

In the Artist’s Studio<br />

Signed and dated lower right: Labroue 1836<br />

Watercolour and ink<br />

17 ¾ x 22 in. (45 x 56 cm.)<br />

[Plate 15]<br />

38.<br />

MARIE LAURENCIN (Paris 1883 – 1956 Berlin)<br />

Self-Portrait<br />

Signed and dated lower right: Marie Laurencin<br />

22 Juillet 1903<br />

Black chalk<br />

7 x 8 in. (17.5 x 20 cm.)<br />

39.<br />

ARMAND LAUREYS<br />

(Brussels 1867 – after 1925 Brussels)<br />

Studio Interior<br />

Signed top right: Arm. Laureys<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

12 ½ x 9 in. (32 x 24 cm.)<br />

40.<br />

ADOLPHE LELEUX (Paris 1812 – 1891 Paris)<br />

Interior of the Louvre<br />

Signed lower left: Adolphe Leleux<br />

21 x 31 in. (52 x 77 cm.)

41.<br />

STEPHEN LEWIN (Active London 1890 – 1908)<br />

Portrait of the Artist at the Easel<br />

Signed and dated lower right: S. Lewin 91<br />

Oil on wood<br />

12 x 9 in. (31 x 23 cm.)<br />

42.<br />

SIR COUTTS LINDSAY<br />

(Balcarres, Collinsburgh 1824 – 1913 London)<br />

Self-Portrait<br />

Oil on mahogany panel<br />

30 x 36 in. (76.2 x 91.5 cm.)<br />

43.<br />

MAXIMILIAN LUCE (Paris 1858 – 1941 Paris)<br />

The Artist’s Studio in Rue Vavin<br />

Signed lower right: Luce and inscribed and dated on<br />

the stretcher: ‘Ma chambre, rue Vavin, 1875’<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

11.8 x 9 ½ in. (29.9 x 24.1 cm.)<br />

44.<br />

CATHERINE LUSURIER<br />

(Paris 1752 – 1781 Paris)<br />

Portrait of the Artist Carle Vernet<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

13 ⅝ x 10 ⅜ in. (34 x 26 cm.)<br />

[Plate 7]<br />

45.<br />

ANDREW McCALLUM<br />

(Nottingham 1821 – 1902 London)<br />

Self-Portrait of the Artist in a Rocky Landscape<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

28 ½ x 22 in. (72.5 x 55.9 cm.)<br />

46.<br />

JACOPO PALMA, IL GIOVANE<br />

(Venice 1544 – 1628 Venice) and<br />

GIACOMO FRANCO (Venice 1550 – 1620 Venice)<br />

Painting and Sculpture<br />

Etching<br />

6 ¼ x 7 ¼ in. (15.6 x 18.2 cm.)<br />

47.<br />

HERMANN MAX PECHSTEIN<br />

(Zwickau 1881 – 1955 Berlin)<br />

Self-Portrait<br />

Signed with monogram and dated lower right:<br />

HMP ‘17<br />

Pen and ink<br />

13 x 9 ⅜ in. (32.5 x 23.5 cm.)<br />

48.<br />

ISIDORE-ALEXANDRE-AUGUSTIN PILS (Paris<br />

1813 – 1875 Douarnenez)<br />

A Sculptor in his Studio<br />

Signed and dated on the lower right: 1872 I Pils<br />

Watercolour over traces of black chalk<br />

11 x 8 in. (28.1 x 20.2 cm.)<br />

[Plate 8]<br />

49.<br />

GIOVANNI MARCO PITTERI<br />

(Venice 1702 – 1786 Venice)<br />

Portrait of Giovanni Battista Piazzetta<br />

Engraving<br />

20 ¾ x 16 ½ in. (51.8 x 41 cm.)<br />

50.<br />

JEAN ALPHONSE ROEHN<br />

(Paris 1799 – 1864 Paris)<br />

Portrait of an Artist painting her Self-Portrait<br />

Signed lower right: alp. Roehn.<br />

Oil on panel<br />

10 ¼ x 8 in. (26 x 20 cm.)<br />

[Illustrated on the front cover]<br />

51.<br />

GEORGES ROUSSIN<br />

(St-Denis 1854 - 1929)<br />

The Artist’s Studio<br />

Signed lower left: G Roussin<br />

Oil on panel<br />

8 ½ x 11 in. (21 x 28 cm.)<br />

52.<br />

THOMAS ROWLANDSON<br />

(London 1756 – 1827 London)<br />

Manufacturers of Old Masters at Work<br />

Watercolour<br />

15 ¾ x 18 ¾ in. (40.5 x 48 cm.)<br />

[Plate 9]<br />

53.<br />

AUGUSTIN DE SAINT-AUBIN<br />

(Paris1736 – 1807 Paris), engraving after CHARLES<br />

NICOLAS COCHIN the YOUNGER<br />

(Paris 1715 – 1790 Paris)<br />

Portrait of the artist Jacques Du Mont, called Le Romain.<br />

Engraving<br />

7 ¾ x 5 ¾ in. (19.2 x 14.3 cm.)57.<br />

54.<br />

ENOCH SEEMAN<br />

(Danzig c.1690 – 1744 London)<br />

Self-Portrait with the Painter’s Brother Isaac<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.2 cm.)

55.<br />

JOHANN GOTTFRIED SCHADOW<br />

(Berlin 1764 – 1850 Berlin)<br />

The Exhibition Audience<br />

Signed and dated in pencil: Dir. Schadow 26 May 1831<br />

Zincograph<br />

12 ½ x 23 in. (31 x 57.5 cm.)<br />

56.<br />

JOHANN GOTTFRIED SCHADOW<br />

(Berlin 1764 – 1850 Berlin)<br />

The Old Painter<br />

Zincograph<br />

14 x 10 in. (34.9 x 25.2 cm.)<br />

57.<br />

GERARD VAN SPAENDONCK<br />

(Tilburg 1746 – 1822 Paris)<br />

Self-Portrait seated at a Table, turned to the right<br />

Black and white chalk, heightened with white,<br />

on light brown paper<br />

14 ¼ x 12 in. (36.7 x 28.8 cm.)<br />

[Plate 6]<br />

58.<br />

AUSTIN OSMAN SPARE<br />

(London 1886 – London 1956)<br />

Self-Portrait with Animal Forms<br />

Signed and dated: Jan AD 1906 Austin O. Spare<br />

Pencil, black ink and grey wash heightened with gold<br />

14 ½ x 10 ¼ in. (37 x 26 cm.)<br />

59.<br />

PHILIPPE JOSEPH TASSAERT<br />

(Antwerp 1732 – 1803 London)<br />

The Drawing Academy<br />

Brush and black ink, grey and black wash over black<br />

chalk, on yellowish paper<br />

13 x 12 ¼ in. (33.2 x 30.8 cm.)<br />

60.<br />

PIETRO TESTA (Lucca 1612 – 1650 Rome)<br />

Self-Portrait<br />

Inscribed: Ritratto di Pietro Testa Pictore eccel. te/<br />

delineavit et sculpsit Romae. Superiorum permisu/ fran.<br />

co. Collignon formis<br />

Etching<br />

9 x 6 ⅝ in. (22.5 x 16.6 cm.)<br />

61.<br />

JOHANN HEINRICH TISCHBEIN<br />

(Haina 1722 – 1789 Kasel)<br />

Self-Portrait in Venetian Masquerade Costume<br />

Monogrammed and dated centre right: HT Pinx / 1753<br />

Inscribed on original canvas support: N=o.98<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

33 ½ x 27 in. (85.1 x 68.6 cm.)<br />

[Plate 4]<br />

62.<br />

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC<br />

(Albi 1864 – 1901 Malromé)<br />

Artist Painting (verso)<br />

Head of a Man, in Profile, wearing a Hat (recto)<br />

With the artist’s stamped monogram<br />

(Lugt 1338, lower left recto)<br />

Pencil on paper<br />

10 ⅝ x 6 ¾ in. (27 x 17 cm.)<br />

[Illustrated on the back cover]<br />

63.<br />

JACOB VAN TOORENVLIET<br />

(Leiden c. 1635/41 – 1719 Leiden)<br />

An Allegory of Painting<br />

Oil on copper<br />

10 ¼ x 12 ¾ in. (26 x 32.5cm.)<br />

[Plate 12]<br />

64.<br />

CHARLES TURNER, A.R.A<br />

(Oxfordshire 1773 – 1857 London)<br />

Portrait of Paul <strong>Colnaghi</strong><br />

Brush and sepia<br />

15 ½ x 12 ½ in. (39 x 32 cm.)<br />

65.<br />

ÉMILE-JEAN-HORACE VERNET<br />

(Paris 1789 – 1863 Paris)<br />

Raphael at the Vatican<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

15 ½ x 11 ¾ in. (39.2 x 30 cm.)<br />

Preliminary sketch for the 1833 Salon painting<br />

66.<br />

ÉMILE-JEAN-HORACE VERNET<br />

(Paris 1789 – 1863 Paris)<br />

Raphael at the Vatican<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

18 x 24 ¼ in. (45.7 x 61.6 cm.)<br />

Preliminary sketch for the 1833 Salon painting<br />

67.<br />

CHARLES FRIEDRICH ALFRED VETTER<br />

(Kahlstadt 1858 – 1936 Kahlstadt)<br />

A Visit to the Munich Pinakothek<br />

Signed and dated lower right: C Vetter 1917<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

25 x 23 ¼ in. (63.5 x 69 cm.)<br />

[Plate 14]<br />

68.<br />

FRIEDRICH GEORG WEITSCH<br />

(Braunschweig 1758 – 1828 Berlin)<br />

Self-Portrait<br />

Etching<br />

4 ½ x 3 ½ in. (11.3 x 8.9 cm.)

Plate 15<br />

ALPHONSE DE LABROUE<br />

(Metz (?) 1792 – 1863 Metz)<br />

In the Artist’s Studio<br />

Cat.37

Back Cover:<br />

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC<br />

(Albi 1864 – 1901 Malromé)<br />

Artist painting (verso)<br />

Head of a Man, in Profile, wearing a Hat (recto)<br />

Cat.62<br />

COLNAGHI<br />

15 OLD BOND STREET<br />

LONDON W1S 4AX<br />

UNITED KINGDOM<br />

Tel. +44-20-7491-7408<br />

Fax. +44-20-7491-8851<br />

contact@colnaghi.co.uk<br />

www.colnaghi.co.uk<br />

EMANUEL VON BAEYER<br />

130-132 HAMILTON TERRACE<br />

LONDON, NW8 9UU<br />

UNITED KINGDOM<br />

Tel & Fax: + 44-20-7372-1668<br />

art@evbaeyer.com<br />

www.evbaeyer.com