Master Drawings 2013 - Colnaghi

Master Drawings 2013 - Colnaghi

Master Drawings 2013 - Colnaghi

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

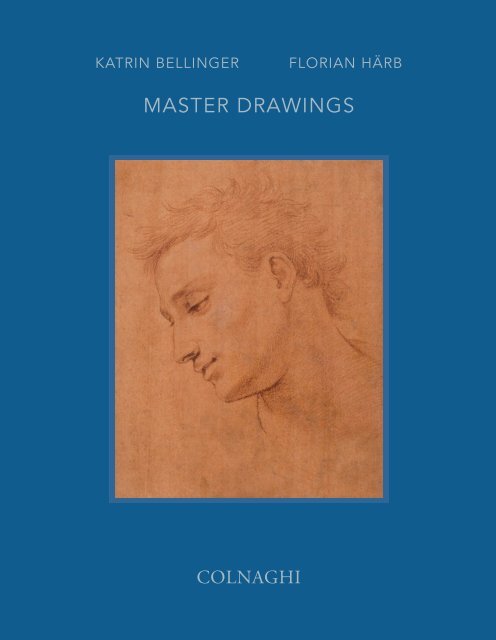

KATRIN BELLINGER<br />

FLORIAN HÄRB<br />

MASTER DRAWINGS<br />

COLNAGHI

KATRIN BELLINGER<br />

FLORIAN HÄRB<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

We would like to express our gratitude to the many<br />

friends and scholars whose generous help, admirable<br />

expertise, and thorough research, have unearthed a<br />

wealth of new information on many of the drawings<br />

presented here, some of which have not been seen<br />

in public for over half a century.<br />

MASTER DRAWINGS<br />

<strong>2013</strong><br />

Stijn Alsteens, Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari, Laura<br />

Bennett, David Bindman, Marco Simone Bolzoni, Mark<br />

Brady, Virginia Brix, Caroline Corrigan, Sue Cubitt, Gail<br />

Davidson, Ursula Verena Fischer Pace, Gino Franchi,<br />

Francesco Grisolia, Christina Grummt, Clémentine<br />

Gustin-Gomez, Niall Hobhouse, Peter Iaquinandi, Paul<br />

Joannides, Gerhard Kehlenbeck, David Lachenmann,<br />

Thomas Le Claire, Petra Lüer, Alexandra Murphy, Peter<br />

Prange, Simonetta Prosperi Valenti Rodinò, Jean-Claude<br />

Sicre, Chiara Travisonni, Rollo Whately, Richard Whatling,<br />

and Eunice Williams.<br />

Our particular thanks go to Livia Schaafsma, Gay<br />

Naughton, and Martin Grässle, for their tireless efforts<br />

in the preparation of the catalogue.<br />

KATRIN BELLINGER / FLORIAN HÄRB<br />

COLNAGHI

GIULIO PIPPI, CALLED GIULIO ROMANO<br />

Rome c. 1492/99–1546 Mantua<br />

1<br />

BACCHUS AS AUTUMN<br />

Pen and brown ink, brown wash<br />

238 × 98 mm, the upper corners chamfered<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Unidentified collector, his inscription, lower right, Jul. Romano.<br />

Sir Thomas Lawrence (L. 2445)<br />

Samuel Woodburn, purchased in 1836 by<br />

Lord Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere (L. 2710b),<br />

by descent<br />

Sale: London, Sotheby’s, <strong>Drawings</strong> by Giulio Romano and other<br />

16th Century masters, 5 December 1972, lot 53, illustrated<br />

Private collection<br />

LITERATURE<br />

Catalogue of the Ellesmere Collection of <strong>Drawings</strong> at<br />

Bridgewater House, London, 1898, cat. no. 157<br />

F. Hartt, Giulio Romano, 2 vols., New Haven, 1958, I, pp. 186<br />

and 301, cat. no. 242<br />

S. Massari, Giulio Romano pinxit et delineavit. Opere grafiche<br />

autografe di collaborazione e bottega, exhibition catalogue,<br />

Rome, Istituto nazionale per la grafica, 1993, pp. 181–83, under<br />

no. 170<br />

Although this drawing of the god of wine was among the<br />

most elegant and charming of those by Giulio formerly<br />

in the Ellesmere collection, it has been little discussed.<br />

Fig. 1<br />

It shows Bacchus as Autumn and was one of a quartet<br />

of allegorical figures of the Seasons; the other three<br />

drawings (representing Flora, Pomona and, probably,<br />

Saturn) are lost but the four, maybe originally on the same<br />

sheet, were etched by Battista del Moro on a single plate<br />

(283 × 409 mm, Fig. 1), c. 1540. Bacchus in the drawing<br />

and the etching has the same dimensions, and this was<br />

probably true of the other figures too.<br />

Fredrick Hartt believed the four figures to have been<br />

planned for execution as garden statuary, an obviously<br />

appropriate role for the Seasons. He was surely correct<br />

about their general purpose and function, but it is far from<br />

certain that they were made for the walled garden of the<br />

Appartamento di Troia in the Palazzo Ducale as he pro -<br />

posed, and they have no apparent thematic or stylistic<br />

relation to the three sharply executed pen drawings – two<br />

of them depicting pendant narratives of Hercules and<br />

Apollo – also conjecturally linked by Hartt to this scheme<br />

and interpreted as designs for reliefs.<br />

As drawn here Bacchus is relatively flat in modelling and,<br />

although he glances over his shoulder, was clearly intended<br />

for an isolated figure. The technique and the sharp<br />

illumination from the left, casting a thin shadow on the<br />

vine that curls behind him, suggests that he was to be in<br />

shallow rather than high relief, a supposition reinforced by<br />

lack of any three-dimensional emphasis: it is notable that<br />

hatching is applied only minimally. However, the denser<br />

and fuller shadows in the etching rather suggest high<br />

relief, or even free-standing forms, as both Hartt and<br />

Massari concluded, so the precise purpose of Bacchus<br />

and the other figures must be left open.<br />

As for location the Seasons seem more suitable for the<br />

predominantly convivial iconography of Palazzo Te than<br />

the Palazzo Ducale, but the Seasons can now be found in<br />

neither building. Bacchus, however, appears twice among<br />

the stucco panels in the Te, as an isolated figure in the<br />

Camera delle Aquile of 1527–28 1 and leading the vintage<br />

in the Camera degli Stucchi of c. 1530. 2 This Bacchus<br />

comes closer in design to the former and was no doubt<br />

con sciously developed from it; Giulio continually re-cycled<br />

and modified earlier ideas.<br />

3<br />

4

GIULIO PIPPI, CALLED GIULIO ROMANO<br />

3<br />

1<br />

The handling of the present drawing is very characteristic,<br />

with its long, thinly penned, slightly wavering contours,<br />

frequently broken to suggest mobility; the light wash<br />

thrown across the forms, more to establish atmosphere<br />

and light than for modelling, looks back to certain drawings<br />

by Raphael, such as the British Museum’s study for<br />

the Disputa, which shows Giulio’s master at his airiest; but<br />

the drawing finds a parallel too in the work of Giulio’s<br />

slightly younger contemporary, Parmigianino, whose artificiality<br />

of form, playful treatment of classical antiquity,<br />

and breezy employment of wash find echoes in Giulio.<br />

Giulio would, of course, have known prints after Parmigianino,<br />

including his mythologies and he would have responded<br />

to Parmigianino’s combination of angularity and<br />

softness. But if the drawing recalls Giulio’s predecessors<br />

and contemporaries, it also anticipates Tiepolo and his<br />

world. This proto-rococo light-heartedness co-exists in<br />

Giulio with the Sturm and Drang of the Sala dei Giganti<br />

and the Sala di Troia, and lightness and wit reach a peak<br />

in his work in the mid-1530s, a date stylistically appropriate<br />

for this Bacchus with his pronounced elongation and<br />

relaxed ease of demeanour.<br />

PAUL JOANNIDES<br />

6

GIORGIO VASARI<br />

Arezzo 1511–1574 Florence<br />

2<br />

SAINT EUSTACE<br />

Pen and brown ink, brown wash over black chalk<br />

258 × 99 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Probably Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici<br />

Probably Gualtiero van der Voort, by 1657<br />

J.P. Zoomer (Lugt 1511), his inscription Geo: Vasari<br />

Mely Ehrensberger, Bern, her sale: London, Christie’s,<br />

29 June 1971, lot 121, illustrated<br />

Charles E. Slatkin Galleries, New York<br />

Private collection<br />

EXHIBITIONS<br />

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, European <strong>Drawings</strong> from<br />

Canadian Collections, 1500–1900, ed. M. Cazort-Taylor, 1976,<br />

cat. no. 3, illustrated (catalogue entry by D. McTavish)<br />

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Leonardo da Vinci,<br />

Michelangelo, and the Renaissance in Florence, ed. D. Franklin,<br />

2005, cat. no. 109, illustrated (catalogue entry by F. Härb)<br />

LITERATURE<br />

L. Corti, Vasari, catalogo completo dei dipinti, I gigli dell’arte,<br />

no. 3, Florence, 1989, p. 37<br />

F. Härb, Giorgio Vasari. Die Zeichnungen, Ph.D. thesis,<br />

University of Vienna, 1994, 3 vols. 1994, I, p.117, cat. no. 95,<br />

II, pl.95<br />

This carefully executed drawing relates to Vasari’s tripartite<br />

altarpiece of the Allegory of the Immaculate Conception,<br />

painted in 1542–43 for the family chapel of Biagio Mei in<br />

S. Pietro Cigoli, Lucca, and now in the Museo di Villa<br />

Guinigi of that town. It is a study, with several differences,<br />

for the figure of Saint Eustace in the right side panel<br />

(Fig. 1). The left panel is dedicated to San Biagio (St. Blaise),<br />

patron saint of the donor. According to the Ricordanze,<br />

the artist’s account book, Vasari received the commission<br />

on 20 July 1542 and completed the painting on 31 October<br />

1543. He further states that the patron wished his altarpiece<br />

to be similar to that of the same subject finished<br />

about a year earlier, in 1541, for the chapel of Vasari’s<br />

friend and patron, Bindo Altoviti, in the church of Santi<br />

Apostoli, Florence. 1 This was Vasari’s first major altarpiece<br />

for a Florentine Church and proved to be extremely popular.<br />

Several small-scale versions and large replicas by the<br />

artist and his workshop, as well as numerous variations by<br />

subsequent Florentine painters well into the seventeenth<br />

century testify to the great success of Vasari’s painting. 2<br />

While the Lucca altarpiece is largely based on Altoviti’s<br />

Vasari made numerous changes to the positions and<br />

gestures of the figures and rearranged their disposition.<br />

He also reduced their number by one and added two<br />

lateral panels with saints, thus repeating an altarpiece<br />

type that he had first employed in his Descent from the<br />

Cross at Camaldoli (1539–40), and then used throughout<br />

his career. 3<br />

A large drawing by Vasari in the Louvre shows the Lucca<br />

altarpiece set in its architecture, with the donor’s coat of<br />

arms and additional grotesque decoration.<br />

It is not known if it was ever executed<br />

as such, for its original setting<br />

is now lost (Fig. 2). 4 The Louvre drawing<br />

matches the Lucca paintings in<br />

most details, even the figures in the<br />

side panels correspond closely. This<br />

is remarkable as such finished drawings<br />

were usually made at an early<br />

stage in the design process and were<br />

almost always subject to subsequent<br />

modifications. Given that the Louvre<br />

drawing lacks virtually any pentimenti,<br />

it is quite conceivable that it was<br />

made as a ricordo of the altarpiece<br />

rather than as a preparatory design.<br />

The figure of Saint Eustace in the present<br />

drawing differs from that in the<br />

Louvre sheet and the painting, respectively.<br />

In the latter, Vasari gave<br />

the figure a stronger twist, bringing it<br />

Fig. 1<br />

in more line with the Mannerist ideal<br />

of the figura serpentinata. By simultaneously<br />

showing the figure’s front and back he achieved a<br />

highly artificial effect for which, on another occasion, he<br />

was specifically praised by his early mentor, Pietro Aretino,<br />

in a letter of 15 December 1541. 5 The Lucca painting was<br />

executed a few years after Vasari’s return from a prolonged<br />

stay in Bologna (1539–40), where Parmigianino’s Emilian<br />

works had a strong impact on his style. This is particularly<br />

3<br />

8

GIORGIO VASARI<br />

3<br />

2<br />

notable in the fine cross-hatching and curved parallel hatching<br />

of this drawing. Another source, as David McTavish has<br />

noted, was Dürer’s famous Saint Eustace engraving of 1501. 6<br />

The reclining dog and the deer’s head in the drawing<br />

derive directly from the print. While Vasari ultimately did<br />

not use the dog in the painting, the foreshortened head of<br />

another in the lower left is clearly borrowed from that in<br />

the centre right of Dürer’s print. Dürer’s engravings were<br />

greatly admired among Florentine artists – Pontormo<br />

quoted them in his Certosa di Galluzzo fresco cycle – and<br />

Vasari used them in his own compositions throughout his<br />

career.<br />

The fairly complex iconography of the Immaculate Conception<br />

is typical of the allegorical paintings Vasari made<br />

early in his career. Often these were devised with the help<br />

of humanists. According to his Descrizione, the autobiographical<br />

account of his own works at the end of the 1568<br />

edition of the Vite, Vasari devised the iconography with<br />

his patron Altoviti and with the help of molti comuni amici,<br />

uomini letterati, one of whom may have been Giovanni<br />

Pollastra, Vasari’s advisor and early mentor at Arezzo. 7 As<br />

David Franklin has pointed out, the iconography is essentially<br />

based on a conflation of two passages in the Old<br />

Testament, Genesis 3:15 (the Virgin as Second Eve to bring<br />

about the vanquishing of the serpent) and Revelation 12:1<br />

(the Woman of the Apocalypse). 8 It has also been prev -<br />

iously noted that Vasari took recourse to Rosso Fiorentino’s<br />

now-lost cartoon for one of the lunettes in the atrium<br />

of SS. Annunziata, Arezzo, depicting the Virgin as Second<br />

Eve, a concetto that was devised by Pollastra. Vasari was<br />

familiar with Rosso’s designs, which he described in the<br />

artist’s Vita, and he also owned Rosso’s small-scale model<br />

(probably wooden with drawings) of the entire decoration.<br />

9 The figures of Adam and Eve, bound to the Tree of<br />

Knowledge, and the serpent with a human upper body,<br />

depend on Rosso’s designs, known by several copies of<br />

now-lost drawings by Rosso. 10<br />

Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joshua, David, and the other<br />

Kings in succession, according to the order of time; all I<br />

say, bound by both arms, excepting Samuel and John the<br />

Baptist, who are bound by one arm only, because they<br />

were blessed in the womb.” The idea to arrange the<br />

figures ‘according to the order of time’ almost certainly<br />

comes from Sogliani’s Dispute over the Immaculate Conception<br />

of 1531– 36, now in the Galleria dell’Accademia,<br />

Florence, where such order is kept.<br />

A drawing by Vasari of Saint Eustace is mentioned in a<br />

letter of 19 November 1657, written by Paolo Del Sera to<br />

the great collector Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici regarding<br />

an exchange of drawings between the latter and the<br />

Dutch collector Gualtiero van der Voort. According to this<br />

letter, Leopoldo received seventeen drawings from Van<br />

der Voort, who in turn chose only seven, among them<br />

quel Sant’Eustachio del Vasari. Apparently van der Voort<br />

did not aim at the sheets of the highest quality, for, at<br />

least in Del Sera’s view, he selected “not even the most<br />

exquisite drawings” (neanco de più esquisiti). It is not inconceivable,<br />

even likely, that the present drawing, which<br />

bears the stamp of the Dutch art dealer Jan P. Zoomer<br />

(1641–1724), is to be identified with that formerly in the<br />

collection of Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici. 11<br />

Vasari’s extensive description of the Altoviti painting applies<br />

largely also to the Lucca altarpiece. The upper register<br />

shows the Virgin, “clothed by the sun and crowned<br />

with twelve stars” and supported by angels. With her right<br />

foot she steps on the horns of the serpent, whose hands<br />

are bound behind his back and whose tail is wound<br />

around the trunk of the tree. Bound to the roots of the<br />

Tree of Knowledge in the center are Adam and Eve (“the<br />

first transgressors of the commandment of God”). Then,<br />

Vasari writes, “bound to the other branches [are] Abraham,<br />

Fig. 2<br />

10

GIORGIO VASARI<br />

Arezzo 1511–1574 Florence<br />

3<br />

COSIMO REVIVING THE TOWN<br />

OF VOLTERRA<br />

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white<br />

over black chalk on blue paper, squared in black chalk<br />

152 x 186 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Sale: London, Christie’s, 23 June 1970, lot 54, illustrated<br />

Ralph Holland, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, by descent<br />

EXHIBITIONS<br />

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Hatton Gallery, Italian and other<br />

<strong>Drawings</strong>, 1500–1800, 1974, cat no. 10, pl. VI (cat. by<br />

K. Rowntree and R. Holland)<br />

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Hatton Gallery, Italian <strong>Drawings</strong><br />

(1525–1570) from the Collection of Ralph Holland, 1982,<br />

cat. no. 8, pl. IIa<br />

LITERATURE<br />

Antichità Viva, IX, 1970, 3, p. 71, illustrated<br />

C. Monbeig-Goguel, Vasari et son Temps, Inventaire Générale<br />

des Dessins Italiens, I, Paris, 1972, under cat. no. 210<br />

E. Allegri and A. Cecchi, Palazzo Vecchio e i Medici, guida<br />

storica, Florence, 1980, p. 152, cat. no. 7, illustrated<br />

F. Härb, Giorgio Vasari. Die Zeichnungen, Ph.D. thesis,<br />

University of Vienna, 3 vols., 1994, I, p. 197, cat. no. 238, II,<br />

pl. 238<br />

R.A. Scorza, “Vasari and Gender: A New Drawing for the Sala<br />

di Cosimo I,” in Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 1995– 96,<br />

pp. 65–74, illustrated<br />

F. Härb in D. Franklin (et al.), Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo<br />

and the Renaissance in Florence, exhibition catalogue, Ottawa,<br />

National Gallery of Canada, 2005, p. 300, under cat. no. 110,<br />

and p. 355<br />

towns. In a letter to Cosimo of 12 May 1558 Vasari refers<br />

to the Sala, except for the floor, as finished. 1<br />

Devised by the humanist Cosimo Bartoli the iconographic<br />

programme for the ceiling paintings survives in a letter to<br />

Vasari written in 1556, which contains also the invenzioni<br />

for the Sala di Cosimo il Vecchio and that of Cosimo’s<br />

father, Giovanni dalle Bande Nere. 2 The initial programme<br />

for the Sala di Cosimo I, however, included only<br />

one allegory of a Tuscan town, Pisa, while the other compartments<br />

were to show various virtues associated with<br />

the Duke. These virtues were later abandoned in favour of<br />

a programme emphasising Cosimo’s role as a reviver of,<br />

and builder of fortifications in, the towns of his dominion.<br />

Here, as Rick Scorza has pointed out, Vasari and Bartoli<br />

drew on the classical motif of Roma resurgens, the reviving<br />

of towns by Roman Emperors frequently represented<br />

on Roman coins. The Tuscan towns are either shown as<br />

men or women, depending on their names’ gender. 3 This<br />

programme is also fully developed in a large and finished<br />

design for the entire ceiling decoration in the Louvre (Fig.<br />

2). 4 Subsequently, however, the individual scenes as<br />

shown in the Louvre drawing were partially rearranged. 5<br />

Our drawing shows Cosimo reviving the old Etruscan<br />

Town of Volterra and is a study for the compartment to<br />

the right of the tondo with Cosimo among his Architects,<br />

Sculptors and Engineers, a damaged drawing for which is<br />

preserved in the Castello Sforzesco, Milan. 6 It was almost<br />

certainly part of a large and highly finished design for the<br />

entire ceiling that was presented to Duke Cosimo for approval.<br />

Two other such drawings, executed in the same<br />

technique on blue paper with their shape corresponding<br />

to that of the ceiling painting, have come down to us. To<br />

3<br />

In 1556, shortly after work began in the Quartiere degli<br />

Elementi at the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Vasari and his<br />

team embarked on the decoration of the Quartiere di<br />

Leone X. Named after the first Medici pope, Leo X<br />

(1475–1521), these quarters consisted of six rooms and a<br />

small chapel that formed Duke Cosimo I’s private chambers.<br />

This drawing relates to the ceiling decoration in one<br />

of these rooms, known as the Sala di Cosimo I (Fig. 1).<br />

More specifically, it is a study for one of eight spandrel<br />

paintings flanking the four tondi in the vault, depicting<br />

significant events in the life of the Duke. Each spandrel<br />

shows Cosimo together with various allegories of Tuscan<br />

Fig. 1<br />

12

GIORGIO VASARI<br />

3<br />

3<br />

the left of the tondo Vasari depicted Cosimo reviving the<br />

Town of Fivizzano, for which a study, in the same technique<br />

and spandrel shape as ours, is at the Yale University<br />

Art Gallery, New Haven. 7 Initially, however, as can be seen<br />

in the Louvre drawing, the Fivizzano scene was projected<br />

to the left of Cosimo visiting the Fortifications of Elba, while<br />

the town of Pistoia would have formed the pendant to our<br />

scene to the left of Cosimo among his Architects, Sculptors<br />

and Engineers. Eventually the Pistoia scene was transferred<br />

to the opposite wall. A third study for one of the eight spandrels,<br />

showing Cosimo reviving the Town of San Sepolcro, is<br />

at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (Fig. 3). 8<br />

The present drawing follows, with some differences, the little<br />

sketch in the large ceiling design at the Louvre. As Scorza<br />

has shown, in the latter drawing the female figure presents<br />

a large crystal of rock salt to Cosimo, alluding to the ancient<br />

city’s salt-works, which Vasari omitted from our design and<br />

the final painting. Instead he showed the Duke awarding a<br />

mural crown to the female figure, who is now simply pointing<br />

with her left arm to a saltpan in the lower right corner. In<br />

the Ragionamenti, Vasari’s hypothetical dialogue in which<br />

he guides Cosimo’s son, Principe Francesco, through the<br />

Palazzo Vecchio, he describes the allegory of Volterra as an<br />

“old woman drawing the Duke’s attention to the salt pans<br />

with boiling saline, and His Excellency places the mural<br />

crown on her head.” 9 The drawing matches the painting<br />

in most details, only the distant view of Volterra is not<br />

included, as was often the case with drawings of this type.<br />

We know from Vasari’s letters that he used to dispatch his<br />

assistants to make topographical sketches of the required<br />

sites, which were then incorporated into the paintings.<br />

Originally, this drawing almost certainly belonged to the<br />

same large and highly finished sheet as those at Ottawa<br />

and New Haven. Their spandrel-like shape is also most<br />

certainly down to Vasari himself, reflecting his working<br />

practice particularly in his later, often time-constrained,<br />

years. It was Vasari (and never an assistant), who prepared<br />

the large ceiling designs, which were then often reviewed<br />

first by his iconographic advisor, Vincenzo Borghini, and<br />

ultimately by Cosimo I. Those reviews occasionally required<br />

changes to either iconographic details or, quite frequently,<br />

the positioning of individual scenes within a greater scheme.<br />

As a result, such large and finished drawings (based on<br />

the size of our drawing, the overall design would have<br />

been about 76 cm in length) were frequently cut in order<br />

to rearrange individual scenes (or replacing them with<br />

new ones) while at the same time avoiding the time-consuming<br />

process of making a new finished drawing from<br />

scratch. The most prominent, though by no means the only,<br />

such drawing, parts of which survive in various collections,<br />

was the so-called cartone grande, a large though in this<br />

case rather sketchy drawing originally also about 76 cm in<br />

length that shows Vasari’s and Borghini’s initial scheme for<br />

the ceiling paintings of the Sala Grande in the Palazzo<br />

Vecchio (1563).<br />

Fig. 2 Fig. 3<br />

14

GIROLAMO MACCHIETTI<br />

Florence 1535–1592 Florence<br />

4<br />

5<br />

HEAD OF A YOUNG MAN<br />

IN PROFILE TO THE LEFT<br />

Red and white chalk, over traces of black chalk,<br />

on red prepared paper<br />

203 × 162 mm<br />

and<br />

HEAD OF A YOUNG MAN<br />

LOOKING DOWN<br />

Red and white chalk, over traces of black chalk,<br />

on red prepared paper<br />

203 × 165 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Sale: London, Sotheby’s, 9 June 1955, lot 52, illustrated<br />

Private collection<br />

LITERATURE<br />

P. Pouncey, “Contributo a Girolamo Macchietti,” in Bollettino<br />

d’arte, 47, 1962, pp. 238–39, figs. 4, 6 [republished in M.Di<br />

Giampaolo, Philip Pouncey, raccolta di scritti (1937–1985),<br />

Rimini, 1994, pp. 86–87, figs. 4, 6]<br />

V. Pace, “Maso da San Friano,” in Bolletino d’Arte, 61, 1976,<br />

p. 81, note 52<br />

M. Privitera, “Girolamo Macchietti a Napoli,” in Arte-Documento.<br />

Rivista di storia e tutela dei Beni Culturali, 4, 1990, p. 118,<br />

note 121<br />

M. Privitera, “Nuovi disegni di Girolamo Macchietti”, in<br />

Paragone, 529–33, 1994, pp. 109–10, 112, note 14, fig. 58b<br />

M. Privitera, Girolamo Macchietti, un pittore dello Studiolo<br />

di Francesco I (Firenze 1535–1592), Milan, 1996, p. 162,<br />

cat. nos. 66–67, illustrated<br />

According to Raffaele Borghini, 1 Macchietti first trained<br />

under Michele Tosini, whose style at the time had become<br />

somewhat dated, but he was soon drawn into the orbit of<br />

Giorgio Vasari who, in 1555, had just been put in charge of<br />

the entire decoration and transformation of the Palazzo<br />

Vecchio, the old seat of the Florentine Republic, into a<br />

modern ducal residence for Cosimo I de Medici. For<br />

about three years, until 1558, Macchietti worked under<br />

Vasari in the Palazzo, together with Cristofano Gherardi<br />

(who died in 1556) and Giovanni Stradanus. Macchietti’s<br />

part in the decoration is difficult to establish with precision<br />

but in 1557 he is documented to have designed the<br />

tapestries for the Sala di Giove and Sala di Ercole. Only<br />

one of these hangings (but no preparatory drawing) survives,<br />

and this suggests that even in these early works<br />

Macchietti had stylistically little to do with his master. One<br />

of the frescoes in the Sala di Cosimo I has recently been<br />

attributed to him, but there the artist worked to Vasari’s<br />

designs. Around 1560 Macchietti left for Rome to broaden<br />

his artistic horizon before returning to Florence in 1563,<br />

the year Vasari began the decoration of the Sala Grande<br />

in the Palazzo Vecchio. Though Macchietti did not enter<br />

the inner circle of Vasari’s Sala Grande workshop<br />

(Stradanus, Battista Naldini, and Jacopo Zucchi, were the<br />

leading figures) he contributed to the vast ephemeral<br />

decorations put up in 1565 on the occasion of the wedding<br />

of Giovanna of Austria and Cosimo’s son, Principe<br />

Francesco I. de’ Medici. From the subsequent decade and<br />

3<br />

Philip Pouncey was the first to recognise the characteristic<br />

hand of Girolamo Macchietti in these two drawings,<br />

which had previously been considered to be by the late<br />

fifteenth and early sixteenth century Florentine painter<br />

Raffaellino del Garbo (1466–1524). And while Pouncey<br />

could see the drawings when they were sold at Sotheby’s<br />

in 1955, all subsequent commentators have known them<br />

but from photographs. The reappearance of these outstanding<br />

drawings today, with their correct attribution<br />

and nearly sixty years after their sale at auction, is thus of<br />

great interest to connoisseurs of Florentine Renaissance<br />

drawings.<br />

Fig. 1<br />

16

GIROLAMO MACCHIETTI<br />

3<br />

4 | 5<br />

a half, with Macchietti’s style now fully developed, date his<br />

most successful paintings, among which are the Adoration<br />

of the Magi in San Lorenzo (1567– 68) and the Martyrdom<br />

of Saint Lawrence in S. Maria Novella (1573), to name but<br />

two of his altarpieces. In circa 1571– 72 he contributed, under<br />

Vasari’s supervision and alongside the élite of the<br />

young Florentine painters, his most famous works, the<br />

panels of the Baths of Pozzuoli and Medea rejuvenating<br />

Jason (Fig. 1), for the Studiolo of Francesco I. de Medici<br />

located adjacent to the Sala Grande in the Palazzo Vecchio.<br />

As has been noted before, our drawings of a Head of a<br />

young Man in Profile to the left and a Head of a young<br />

Man looking down show the same model from a different<br />

angle. Pouncey considered the former a study for the head<br />

of Medea in the Studiolo painting. The similarities between<br />

these two heads are indeed striking. That Macchietti<br />

would have used a drawing of a male model for a female<br />

figure in one of his paintings would not have been<br />

unusual. Indeed, he used a life study of a seated male<br />

nude now at Edinburgh, 2 executed in the same technique<br />

as ours, for the figure of the Virgin in his San Lorenzo<br />

Adoration. 3 More recently, however, Marta Privitera,<br />

suggested that our drawing was made slightly later, as the<br />

same model (though not exactly the same head) appears<br />

in Macchietti’s Glory of Saint Lawrence (Florence, Uffizi) of<br />

1577. 4<br />

Privitera further considered our Head of young Man<br />

looking down to be a study for Macchietti’s tondo of Saint<br />

Lawrence (Florence, collection of Gianfranco Luzzetti),<br />

which she dates to the middle of the 1570s (Fig. 2). 5 And<br />

Fig. 2<br />

while her dating of our drawings to that period has much<br />

to commend it, the drawings may well have been made a<br />

few years earlier, for the head of our Young Man looking<br />

down, with his slighly pointy chin, is extremely close in<br />

type, and likely showing the same model as, Macchietti’s<br />

Louvre study of a seated youth, which is preparatory for a<br />

figure in his Baths of Pozzuoli. 6 The head is also extremely<br />

close to, and may have actually been used for, that of the<br />

Virgin in Macchietti’s altarpiece of the Madonna della<br />

Cintola (Florence, Soprintendenza), which also dates from<br />

circa 1572. It is quite possible, therefore, that the two<br />

drawings were made at the time of, and in the case of the<br />

Head of a Young Man in Profile possibly for one of,<br />

Macchietti’s Studiolo paintings and that he subsequently<br />

reused them in other works.<br />

Macchietti’s drawings oeuvre is relatively small, yet the<br />

surviving sheets reveal him as a highly gifted and meticulous<br />

draughtsman, who took great care in the preparation<br />

for the individual figures in his paintings. His style is highly<br />

independent of Vasari’s or Salviati’s. Like several of his<br />

fellow Studiolo friends, such as Naldini, Maso da San Friano,<br />

or Mirabello Cavalori, he, too, looked instead to the<br />

works and techniques of the artists from the beginning of<br />

the century (that is, Vasari’s and Salviati’s teachers), such<br />

as Andrea del Sarto and his pupils Rosso and, especially,<br />

Pontormo. Like them, but unlike his master Vasari, Macchietti<br />

put the life study at the core of his artistic endeavor.<br />

This is beautifully attested to by several extant figure studies<br />

for his Baths of Pozzuoli and a study of a seated nude for<br />

the Martyrdom of San Lawrence in the Metropolitan<br />

Museum of Art, 7 which are all executed in the same technique<br />

as our drawings, in red (with some white) chalk on<br />

red prepared paper. 8 Paper prepared with colour is a<br />

technique that can frequently be found in artists of the<br />

late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries (thus making<br />

the old attribution to del Garbo somewhat understandable),<br />

as well as in Pontormo’s sketchbooks, but that was<br />

mostly (though not entirely) abandoned by the generation<br />

of Vasari and Salviati. And while emulating the spirit, and<br />

indeed the technique and media of Andrea’s or Pontormo’s<br />

life studies, our two drawings display a degree of finish<br />

and refinement that the old generation had hardly been<br />

concerned with. Yet it is this particular combination of observation<br />

of nature with the refinement of execution that<br />

distinguishes Macchietti and other Studiolo artists from<br />

their great High Renaissance models and fully validates<br />

their much-admired place in the history of Florentine<br />

draughtsmanship.<br />

18

PAOLO FARINATI<br />

Verona 1524–1606 Verona<br />

6<br />

ALLEGORY OF TEMPERANCE<br />

Inscribed by the artist, upper left margin, …sta ma<br />

a questo / stava melio, and numbered in white chalk,<br />

lower right, 16<br />

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk,<br />

heightened with white<br />

260 × 184 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Private collection<br />

Executed in Farinati’s favorite technique on Venetian carta<br />

azzurra (blue paper), this is a characteristic working drawing,<br />

which explores two different poses of a figure of Temperance,<br />

one of the four cardinal virtues. More specifically,<br />

the drawing shows two solutions to the figure’s right arm<br />

and hand, which holds one of this allegory’s best known<br />

attributes, the pitcher of water, with which she extinguishes<br />

a fire (signifying sexual moderation – water putting out the<br />

fires of lust). She is also holding a torch, again symbolizing<br />

the fire defeated by water, and a palm branch. As codified<br />

in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1593) sometime after our<br />

drawing was probably made, Temperance is often depicted<br />

with a bridle (which restrains a horse), an hourglass, a<br />

clock, or an elephant. 1<br />

The precise purpose of this drawing is not known though<br />

it was likely made for one of the houses and villas in and<br />

around Verona that Farinati decorated from the 1550s.<br />

While the figure of Temperance could have been part of a<br />

façade decoration, more likely it would have been destined<br />

for a painted niche or a wall between two windows as part<br />

of a set of painted virtues. Several comparable drawings<br />

of single figures, often allegorical or military in character,<br />

survive. Close in type and style are an Allegory of Arithmetic<br />

in the British Museum, 2 a Venus and Cupid in the<br />

Louvre, 3 and a study of an Allegorical Figure in the Metro -<br />

politan Museum of Art, New York, 4 which also shows an inscription<br />

in Farinati’s characteristic handwriting. The fragmented<br />

handwriting in our drawing, in which the artist<br />

seems to express a preference for one solution over another<br />

may well refer to one, almost certainly the upper one, of<br />

his two alternative designs for the figure’s right arm.<br />

decades. But whereas Farinati’s later years are well documented,<br />

thanks in particular to the survival of his Giornale<br />

(account book, 1573–1606), his early career is obscure. His<br />

first documented work is the altarpiece of Saint Martin,<br />

painted in 1552 for Mantua Cathedral, which recently had<br />

been renovated from Giulio Romano’s plans.<br />

Before that, Farinati is likely to have been most active in<br />

painting façade frescoes, often of antique subjects. By<br />

mid-century, classical Roman history had gained wide -<br />

spread appeal as a subject for fresco decorations throughout<br />

much of Italy. But in Verona, which boasted the most<br />

extensive antique architectural remains in North Italy, such<br />

subjects enjoyed particular popularity. Sadly, the appearance<br />

of Farinati’s early façade frescoes remains largely<br />

hypothetical. They have all been destroyed – like so many<br />

other façade frescoes of this period – and no reliable<br />

evidence for their reconstruction has yet been discovered.<br />

Paolo Farinati enjoyed a longer career than most of his<br />

Vero nese contemporaries. Altogether, he worked in his<br />

birthplace and the surrounding area throughout six<br />

20

ANTONIO VIVIANI, CALLED IL SORDO DI URBINO<br />

Urbino 1560–1620 Urbino<br />

7<br />

THE INCREDULITY OF SAINT THOMAS<br />

Inscribed in pen and brown ink, lower left, Zuchero<br />

Pen and red and brown ink, red wash, over red chalk<br />

331 × 276 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Private collection, France<br />

The composition of this Incredulity of Saint Thomas instantly<br />

brings to mind the foremost works of the Counter-Reform -<br />

ation in Rome in the 1570s. One would think, for instance,<br />

of Federico Zuccaro’s paintings in the Cathedral of Orvieto, 1<br />

or Girolamo Muziano’s paintings in the Ruiz chapel in Santa<br />

Caterina dei Funari, 2 works that served the painters then residing<br />

in Rome as a point of reference for their own work<br />

until the end of the century. Yet even though the composition<br />

of the present drawing is reminiscent of the works of<br />

the 1570s by these two artists, the handling and the style of<br />

the figures and physiognomies suggest a somewhat later<br />

date to approximately the 1580s.<br />

Stylistically, in fact, this sheet belongs squarely to that strand<br />

of Roman painting generally referred to as the maniera<br />

sistina, a hightly characteristic and fairly uniform style employed<br />

by numerous painters who worked on the decorative<br />

projects commissioned by Pope Sixtus V (1585–90),<br />

including such prominent places of papal power as the<br />

Lateran Palace, the Scala Santa, and the Vatican Library.<br />

The draughtsman of our Incredulity of Saint Thomas<br />

belongs here and, more to the point, is certainly to be<br />

found among the numerous painters who hailed from<br />

the Marches to find work in one of the many Sistine<br />

building sites. This is evident in the drawing from such<br />

typical Marchigian features as the slight awkwardness in<br />

the rendering of the anatomies, and a taste for facial types<br />

whose expressions border on the grotesque, such as tiny<br />

and close-set eyes, protruding chins, broad foreheads,<br />

and small and pointed noses. These features are generally<br />

reminiscent of Marchigian draughtsmen in Rome and<br />

particularly of Andrea Lilio (c. 1555– c. 1527) of Ancona;<br />

and it is indeed one of Lilio’s fellow countrymen, Antonio<br />

Viviani, that I believe this beautiful drawing should be given<br />

to. 3<br />

A native of Urbino, Viviani worked shoulder to shoulder<br />

with Lilio on several occasions (in the Scala Santa, the<br />

Vatican Library, in San Girolamo degli Schiavoni). Before<br />

moving to Rome in the early 1580s he had trained in the<br />

workshop of Federico Barocci, who remained a constant<br />

point of reference for Viviani’s entire career. Yet the Baroccesque<br />

streak in Viviani, while always visible in his paintings,<br />

was not all-encompassing; indeed, more than any of Barocci’s<br />

other strict disciples from Urbino, he developed a style that<br />

was both personal and independent of his master’s. While<br />

it is difficult to pin down the hand of the youthful Viviani in<br />

many of the Sistine projects he worked on after his arrival in<br />

Rome, it is even more challenging to identify the drawings<br />

from this budding phase in his career. The present Incre -<br />

dulity of Saint Thomas, however, corresponds extremely<br />

closely with Viviani’s fresco of Fra Girolamo d’Ascoli christening<br />

a Tartar King in the Vatican Library (Fig. 1), first identified<br />

as Viviani’s work by Giuseppe Scavizzi and then by<br />

Alessandro Zuccari. 4 In the figures of Christ and Saint<br />

Thomas, for instance, both the fresco, with its numerous<br />

Baroccesque references, and the drawing, where such references<br />

are just emerging, are extremely close in their rendering<br />

of the draperies and garments, in the gestures of<br />

the protagonists and, above all, in the facial types.<br />

As far as the technique is concerned that Viviani used in<br />

this drawing, one might point out the rare and fascinating<br />

combination of red chalk and watercolour of the same<br />

colour, a technique found but in few drawings of the period,<br />

perhaps the most beautiful of which is Taddeo Zuccaro’s<br />

famous sheet of studies for the Blinding of Elymas and the<br />

Sacrifice at Lystra in the Art Institute of Chicago. 5<br />

Fig. 1<br />

MARCO SIMONE BOLZONI<br />

22

FRANCESCO VANNI<br />

Siena 1563–1610 Siena<br />

8<br />

PORTRAIT OF PASSITEA CROGI<br />

Black, red and white chalk on blue paper<br />

182 × 145 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Sir John Pope-Hennessy, his sale: London, Christie’s,<br />

7 July 1998, lot 85, illustrated<br />

Private collection, New York<br />

LITERATURE<br />

F. Viatte, Dessins Toscans XVI e – XVIII e siècles, I,<br />

1560– 1640, Paris, 1988, under cat. no. 524<br />

Beata Passitea Crogi was the daughter of the painter<br />

Piero Crogi who worked with Arcangelo Salimbeni, Vanni’s<br />

first master and stepfather, as well as father of the betterknown<br />

painter Ventura. A capuchin nun, Passitea was<br />

known for wearing men’s clothes to better help the poor.<br />

In 1597 she left Siena for Florence, and settled in a house<br />

in Via della Colonna with eighteen of her companions,<br />

under the protection of Cristina of Lorraine, wife of Grand<br />

Duke Ferdinando I de‘ Medici. In 1602, she went to France<br />

in the entourage of Ferdinando’s niece, Maria de’ Medici,<br />

who had married King Henri IV of France in 1600. In France<br />

she belonged to the circle of the Queen, denounced as<br />

dévotes et sorcières italiennes in the Duc de Sully’s Mémoires.<br />

She died at Siena on 14 May 1615 and was buried<br />

at the monastery of Saint Egidio. She was later beatified. 1<br />

painter Federico Barocci, whose highly realistic, coloured<br />

chalk portraits made from life exerted a great influence<br />

over Vanni’s drawing style. By the 1590s, Vanni had returned<br />

to Siena where he became the city’s leading<br />

painter providing numerous altarpieces and private devotional<br />

paintings to its churches and confraternities. In circa<br />

1600– 04 he worked again in Rome, where he painted one<br />

of his most famous altarpieces, the Fall of Simon Magus,<br />

for the church of Saint Peter’s in the Vatican, before<br />

returning to Siena for the remaining years of his life.<br />

Another drawing of Passitea Crogi, of equal size and identi -<br />

cal in technique, is in the Louvre. 2 There are some differen -<br />

ces in the expression of the face, with our drawing conveying<br />

a hint of a smile. A third portrait in the same technique<br />

is in the Uffizi, 3 while a drawing by Ottavia Maria Leoni in<br />

the Louvre shows the sitter at a similar age to our sheet. 4<br />

The identification of the sitter is due to an old annotation<br />

on the verso of the Louvre drawing and to the fact that<br />

the physiognomy of the sitter in the drawings closely corresponds<br />

to an anonymous portrait of Passitea formerly in<br />

the collection of Piero Misciattelli (Fig. 1). 5<br />

After his training with Arcangolo Salembeni, Vanni went to<br />

Bologna where he may have worked under Bartolommeo<br />

Passarotti. He absorbed the Carracci classicism, founded<br />

on the close study of nature, before travelling to Rome<br />

and entering the workshop of Giovanni de’ Vecchi. There<br />

he came also in the orbit of the leading Marchigian<br />

Fig. 1<br />

24

VESPASIANO STRADA<br />

Rome c. 1580– c. 1622 Rome<br />

9<br />

ECCE HOMO<br />

Black chalk, pen and brown ink and wash, heightened with<br />

white, indented and squared for transfer in black chalk, on<br />

brown prepared paper<br />

322 × 227 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Artaria & Co. (), Vienna (Lugt 2347)<br />

Private collection, London<br />

According to his biographer, Giovanni Baglione, Vespa -<br />

siano Strada was born in Rome to a Spanish father and<br />

died there at the age of only 36. Active as a painter both<br />

in Rome and central Italy, Strada worked also as a printmaker<br />

and leather decorator. His most important works in<br />

Rome include the frescoes in the Churches of Santa Maria<br />

in Aracoeli, San Giacomo degli Incurabili, Santa Maria<br />

Maddalena, and the cloisters of Sant’Onofrio al Gianicolo<br />

(further frescoes were in the now-lost Churches of Santa<br />

Marta and San Giacomo Maggiore).<br />

The present drawing may reflect some of the artist’s non-<br />

Italian origins, such as the highly expressive realism of the<br />

protagonists, and a training that certainly included the<br />

study of prints by Northern Renaissance masters. Strada’s<br />

authorship of the drawing appears particularly evident if<br />

one compares it with one of his rare connected drawings,<br />

his finished study in the Louvre for the fresco of the Martyr -<br />

dom of St. Feliciano in the Duomo at Foligno (Fig. 1). 1<br />

With the Louvre sheet, our drawing shares the same handling<br />

of the pen, the wash and the hatched, subtly applied<br />

white heightening. In addition, there are also strong affinities<br />

in the faces and figures. There are further close ties<br />

with the figures in the preparatory drawings for the<br />

lunettes in Sant’Onofrio al Gianicolo, one of the artist’s<br />

earliest known works, and above all with the drawing of<br />

the Coronation of the Virgin in the Albertina, Vienna. 2<br />

Strada treated the subject of the Ecce Homo also in two<br />

engravings. These differ in composition from our drawing<br />

but share the same, somewhat caricature-like, figure<br />

types. While it seems likely that the drawing was intended<br />

for an engraving (which may have remained unexecuted<br />

or is not otherwise recorded), the high degree of finish<br />

and the squaring for transfer do not exclude that it was<br />

made in view of a painting.<br />

In his combination of heterogeneous elements that are<br />

not always easy to pin down precisely, Strada reveals himself<br />

as a typical exponent of late Roman Mannerism. The<br />

influences, particularly notable in his engravings, of Dürer<br />

and Lucas van Leyden, and those of the Sienese painters<br />

such as Ventura Salimbeni and Francesco Vanni, are particularly<br />

strong in the present drawing. Its high degree of<br />

finish, typical of his paintings which are strongly influenced<br />

by the Zuccari brothers and the more contem -<br />

porary Cavalier d’Arpino, is even more apparent than in<br />

Strada’s other works and testifies to the great technical<br />

ability of an artist whose drawings are still rare.<br />

FRANCESCO GRISOLIA<br />

Fig. 1<br />

26

GIOVANNI FRANCESCO BARBIERI, CALLED IL GUERCINO<br />

Cento 1591–1666 Bologna<br />

10<br />

A SIBYL READING<br />

Pen and brown ink<br />

248 × 207 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

William Esdaille, 1758–1837 (Lugt 2617)<br />

Francois Alziari, Baron de Malaussena, Paris (Lugt 1887), his sale:<br />

Paris, 18–20 April 1866<br />

Jean Thesmar, Paris (Lugt 1544a), his sale: Paris, 9–10 June 1949<br />

(as “Le Guerchin, Femme lisant,” sold for 20.000 FF)<br />

Private collection, New York<br />

Along with other female single figures, such as the Magdalen,<br />

Lucretia, or Cleopatra, Sibyls, both half or full-length,<br />

were an important subject in Guercino’s oeuvre. Having<br />

allegedly foretold the coming of Christ, these prophetesses<br />

were quickly adopted by the Church as pagan counterparts<br />

to the prophets in the Old Testament. And ever since<br />

Michelangelo’s famous depictions of Sibyls in the Sistine<br />

Chapel, this subject-matter enjoyed great popul arity<br />

among subsequent painters. In Guercino’s relatively early<br />

years, Sibyls feature prominently in the fresco decoration<br />

of the cupola of Piacenza cathedral (1626– 27) and its<br />

related drawings. 1<br />

subsequently by the publisher John Boydell, who reissued<br />

the prints in the 1790s in two folios of eighty-two<br />

and seventy-three plates, respectively. Our drawing was<br />

reproduced in the first volume, entitled Eighty-two Prints,<br />

Engraved by Bartolozzi, & c., from the original Pictures<br />

and <strong>Drawings</strong> of Guercino in the Collection of his Majesty,<br />

vol. 1 (London, n.d.). This volume included also a print by<br />

Bartolozzi after Guercino’s painting of the Libyan Sibyl<br />

(1651) purchased by King George III for the Royal Collection<br />

in the 1760s. 5<br />

From the later 1530s, the decade in which our drawing<br />

was likely made, 2 Guercino made a number of noble and<br />

elegant paintings of various of the twelve Sibyls, often<br />

showing them either writing down their prophecies (as in<br />

Guercino’s famous Persian Sibyl at the Pinacoteca Palatina,<br />

Rome, of 1647) or, as in our drawing or Guercino’s painting<br />

of the Samian Sibyl (1651) formerly in the Spencer<br />

collection at Althorp House and recently acquired by the<br />

National Gallery, London, in an almost ethereal state of<br />

deep engagement with the text before them. Resting<br />

their head, chin, or forehead, on one hand further accentuates<br />

the seriousness of their engagement and contemplation.<br />

3<br />

Our drawing served as a model for a copy preserved in<br />

the Royal Collection at Windsor, most likely made by<br />

Francesco Bartolozzi, who in turn made an engraving of it<br />

in reverse (Fig. 1). 4 From about 1764, after his arrival in<br />

London, Bartolozzi had made numerous engravings of<br />

drawings and paintings by Guercino and other masters in<br />

the Royal Collection. At first these prints were sold indiv -<br />

idually, but many of the copper plates were purchased<br />

Fig. 1<br />

28

FRA SEMPLICE DA VERONA<br />

Verona 1589– 1654 Rome<br />

11<br />

THE VIRGIN SEATED,<br />

TURNED TO THE RIGHT<br />

Red, black and white chalk on buff paper<br />

316 × 250 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Dr. C. R. Rudolf, his sale: London, Sotheby’s, 19 May 1977, lot<br />

75, illustrated (as “Emilian School, first half of the 17th Century”)<br />

Private collection, Italy<br />

LITERATURE<br />

M. Di Giampaolo, “Fra Semplice da Verona: ancora un disegno<br />

per la pala del Redentore,” in Arte veneta, 62, 2005, pp. 118–19,<br />

fig. 1 (reprinted in C. Garofalo, M. di Giampaolo, Scritti sul<br />

disegno italiano 1971– 2008, Florence, 2010, pp. 318–19)<br />

The late Mario Di Giampaolo was the first to identify this<br />

finished chalk drawing, formerly thought to be by an Emi -<br />

lian artist of the seventeenth century, as a study for the<br />

Virgin in Fra Semplice’s altarpiece of Beato Felice receiving<br />

the Christ Child from the Virgin in the Church of the<br />

Santissimo Redentore at Venice (Fig. 1). The altarpiece<br />

was painted in circa 1627– 30 on the occasion of the beatification<br />

of another Capuchin friar, Felix of Cantalice<br />

(1515–1587) by Pope Urban VIII on 1 October 1625. Saint<br />

Felix was the first friar of his order to be beatified (and<br />

later, in 1712 under Pope Clement XI, the first to be<br />

canonised), and it was therefore perhaps no surprise that<br />

Fig. 1<br />

one of his fellow friars, who happened to be a leading<br />

painter of his time, was chosen for this commission. The<br />

altarpiece shows the most notable moment in Saint Felix’s<br />

life, a vision during which he received the Christ Child<br />

from the Virgin. This subject quickly evolved into the<br />

single most important one in the Frate’s oeuvre. After the<br />

beatification of St. Felix, the artist visited numerous<br />

Capuchin monasteries which he supplied with paintings of<br />

that subject. 1<br />

Several drawings related to the figure of the Virgin in the<br />

Redentore altarpiece survive. Our drawing, executed in<br />

coloured chalks, the artist’s preferred technique for figure<br />

studies, comes closest to the figure of the Virgin in the<br />

painting. Another study in the same technique, formerly on<br />

the art market in New York, 2 shows the Virgin in a similar<br />

position to ours, though more upright and with a slightly<br />

different solution to the draperies. The drawing was pos -<br />

sibly made at an earlier stage in the design process. A third<br />

drawing was formerly in the collection of Janos Scholz,<br />

New York. 3 This is executed in the same technique and<br />

shows the Virgin in a similar position, with both arms outstretched,<br />

and ready to hand over the Christ Child to Saint<br />

Felix. In addition to our drawing Di Giampaolo published<br />

an oil bozzetto for the painting (private collection), which<br />

corresponds in most parts with the altarpiece. 4<br />

Although Fra Semplice’s painted oeuvre had long been<br />

well established, he was not identified as a draughtsman<br />

until 1992, when David Lachenmann was able to connect<br />

two drawings (in the same technique as ours), with specific<br />

figures in two of the Frate’s best known paintings. 5 On that<br />

basis numerous other drawings were subsequently added<br />

to Fra Semplice’s drawings oeuvre. Roberto Contini published<br />

a significant group of eight coloured chalk studies of<br />

fellow Capuchin monks, from the Kupferstichkabinett,<br />

Berlin, some of which had been traditionally catalogued as<br />

by Barocci, a slightly earlier master of the coloured chalk<br />

whose work Fra Semplice certainly studied in Rome. 6 Comparable<br />

to Barocci, many of the Frate’s chalk drawings are<br />

detailed studies of heads (often portraits of fellow friars) or<br />

figures. His pen-and-ink drawings have been virtually<br />

unknown. More recently, however, a clearer picture of Fra<br />

Semplice’s pen style, which reveals a strong Venetic in -<br />

fluence, has emerged, as both Roberto Contini 7 and Stefan<br />

Morét 8 have published a number of previously unidentified<br />

composition studies from Berlin and the Martin-von-Wagner-Museum<br />

at Würzburg. Several of these are variations<br />

on our subject of the Vision of St. Felix, further testifying to<br />

the important place this scene held in the Frate’s oeuvre.<br />

30

SIMONE CANTARINI, CALLED IL PESARESE<br />

Pesaro 1612–1648 Verona<br />

12<br />

RINALDO LEAVING ARMIDA, CALLED<br />

TO DUTY BY CARLO AND UBALDO<br />

Inscribed, lower margin, Simon Pesarese<br />

Red chalk<br />

200 × 260 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Colonel Henry Stephen Olivier (1796–1866), Lugt 1373<br />

The emergence of this drawing is of particular importance<br />

for several reasons. It is a wonderful addition to Cantarini’s<br />

corpus of drawings. Its composition and extremely fluid<br />

handling of the chalk show off the delicate and elegant<br />

qualities of his more mature style. Furthermore, it sheds<br />

new light on a small group of known but thus far partly<br />

incorrectly identified drawings made in the same iconographic<br />

context. Here, I would like to thank Guido Arbizzoni,<br />

who kindly alerted me to several illustrations based<br />

upon the same Canto, including the famous illustration by<br />

Bernardo Castello 1 of the scene taking place immediately<br />

prior to that in the present drawing (before Armida faints),<br />

and another from an edition published in Florence in 1825<br />

(Fig. 1), which corresponds so closely to Cantarini’s that<br />

one might suspect its author, the painter Carlo Falcini,<br />

had knowledge of such a project by the artist, perhaps a<br />

set of paintings (fully reflected in the series of prints),<br />

which today is all but dispersed, if indeed ever executed. 2<br />

Depicting a dramatic scene from Torquato Tasso’s epic<br />

poem, Gerusalemme liberata, first published in 1581, this<br />

beautiful drawing shows Rinaldo, Christian soldier in the<br />

First Crusade, abandoning the Saracen sorceress Armida<br />

after being called to his war duties by Carlo and Ubaldo.<br />

More precisely, it shows the moment when Armida, having<br />

first begged and then threatened Rinaldo, faints as he<br />

leaves her behind (Book 16, 59–60).<br />

There are three further drawings that relate to the same<br />

moment in the design process. Their compositions oscillate<br />

between the moment when Carlo and Ubaldo try to<br />

extract Rinaldo from Armida, who uses all her magic to<br />

make him stay, and the subsequent moment, as seen in<br />

the present drawing, when Armida, at long last defeated<br />

by Rinaldo’s sense of duty, passes out. Two red chalk<br />

drawings by Cantarini, a sketchier one at the Museum<br />

Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf, 3 and a more worked-up one at<br />

the Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro (Fig. 2), 4 show the<br />

first moment, while a red chalk drawing in the Staats -<br />

galerie, Stuttgart, which is directly related to ours, shows the<br />

second moment. 5 The Stuttgart drawing is more sketchily<br />

executed than ours and its composition is in reverse,<br />

showing the moment of Armida’s fainting, with Rinaldo in<br />

the centre, listening perplexed to his companions’ calls.<br />

The overall composition of our drawing is extremely close<br />

to that at Rio de Janeiro: the three warriors are arranged<br />

in a similar way and both drawings show the putto hovering<br />

above and breaking his bow. The artist was evidently<br />

working out the composition, trying out different poses<br />

and movements probably for a work for which the preferred<br />

scene was yet to be chosen, if indeed Cantarini was<br />

actually working on a series of paintings or prints inspired<br />

by the famous poem. Unfortunately, while there are both<br />

extant and documented works by Cantarini based on Ari -<br />

osto, such as Angelica and Medoro (Reggio Emilia, Credito<br />

Emiliano) or Ruggero liberating Angelica, 6 to date the<br />

present drawing and its related sheets are the only known<br />

works based upon Tasso’s poem.<br />

ANNA MARIA AMBROSINI MASSARI<br />

Fig. 1 Fig. 2<br />

32

ABRAHAM BLOEMAERT<br />

Gornichem 1566– 1651 Utrecht<br />

13<br />

FOUR STUDIES OF FEMALE HEADS<br />

(RECTO)<br />

FIGURE STUDIES<br />

(VERSO)<br />

Numbered, upper right (recto), 58; and upper right (verso), 60<br />

Red chalk, pen and brown ink, heightened with white<br />

165 × 158 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

André Giroux, his sale: Paris, 18-19 April 1904, part of lot 175<br />

Abraham Bloemaert received his artistic training in<br />

Utrecht and Paris but, unlike many of his contemporaries,<br />

never travelled to Italy. Indeed, apart from two years in<br />

Amsterdam, he worked in Utrecht from 1583 until his<br />

death. Together with Cornelis van Haarlem and Joachim<br />

Wtewael, Bloemaert was one of the last major exponents<br />

of the Northern Mannerist tradition. A career of some sixty<br />

years saw the artist complete around two-hundred paintings,<br />

including landscape, history, and genre subjects. He<br />

was also an extremely gifted draughtsman, praised as<br />

such by his biographer Karel van Mander, among others.<br />

Bloemaert’s greatest legacy was his Konstryk Tekenboek<br />

of 166 engravings made after his drawings by his son<br />

Frederick. These were intended as a teaching aid for<br />

future artists to study and emulate. Although model<br />

books of various types of drawing had a long history in<br />

sixteenth-century Italy, none existed in the Low Countries<br />

prior to the publication of Abraham’s Tekenboek.<br />

The recto of the present sheet contains a number of<br />

studies that reappear in the so-called Cambridge Album,<br />

which contains Bloemaert’s final drawings for the Tekenboek.<br />

1 The head on the top left of our drawing appears on<br />

the right of sheet 13 in the Cambridge Album (Fig. 1), 2<br />

while the head on the top right is replicated on the top<br />

left of sheet 18. 3<br />

The studies of hands on the verso relate to Bloemaert’s<br />

painting of Saint Veronica, now-lost but known by an engraving,<br />

in reverse, by Jacob Matham (Fig. 2). 4 The hands<br />

of the saint holding the Sudarium correspond precisely<br />

with those in our sheet. The head on the lower right of the<br />

recto of our sheet may also relate to that of Saint Veronica.<br />

Matham’s engraving was published in 1605 and the inscription<br />

A. Bloemaeert pinxit along the lower margin<br />

confirms that it was made after a painting. The print’s date<br />

provides a terminus ante for our studies while the date<br />

of circa 1591 for the partial watermark would indicate a<br />

terminus post. 5<br />

Fig. 1<br />

Our drawing formed part of the so-called Giroux Album,<br />

assembled by Hendrick Bloemaert, the artist’s son. Generally<br />

double-sided and drawn in red and white chalk on<br />

light brown paper, drawings from this album can be<br />

3<br />

34

ABRAHAM BLOEMAERT<br />

3<br />

13<br />

identified by the distinctive numbering in pen and brown<br />

ink in the upper right corner. They belonged to the<br />

painter, photographer, and art dealer, André Giroux<br />

(1801–1879) and were dispersed at his sale in Paris in 1904.<br />

Compar able drawings from that album are in the Musée<br />

des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, 6 the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los<br />

Angeles, 7 and the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. 8<br />

Fig. 2<br />

36

CHARLES DE LA FOSSE<br />

Paris 1636–1716 Paris<br />

14<br />

STUDIES FOR MINERVA AND<br />

OTHER OLYMPIAN GODS<br />

Numbered on the verso, 10<br />

Red, black and white chalk on buff paper<br />

382 × 270 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Charles E. Slatkin Galleries, New York, 1967<br />

Mrs. Betty Reitman, Montreal<br />

EXHIBITIONS<br />

New York, Charles E. Slatkin Galleries, Selected <strong>Drawings</strong>,<br />

1967, cat. no. 20a, pl. 25<br />

Ottawa, National Gallery of Art, Canada, Watteau and his<br />

World, 2000 (ex-catalogue)<br />

LITERATURE<br />

E.A. Standen, “Ovid’s Metamorphoses: A Gobelins Tapestry<br />

Series,” in Metropolitan Museum Journal, XXIII, 1988,<br />

pp. 159–60, fig. 21<br />

A. Chéreau, Charles de la Fosse et le Grand Décor (1636–1716),<br />

doctoral thesis, Université de Paris IV, 1992, cat. no. 47, illustrated<br />

P.J. Fidler, “A drawing by Charles de Fosse identified,” in<br />

Source Notes in the History of Art, XIV, no. 4, 1995, pp. 34–38<br />

C. Gustin-Gomez, Charles de Fosse, 1636–1716, catalogue<br />

raisonné, 2 vols., Dijon, 2006, II, p.263, cat. no. D198, illustrated<br />

Crozat’s sumptuous residence in the rue de Richelieu bet -<br />

ween 1704 and 1707 but now destroyed. 2 In fact, de la<br />

Fosse treated this subject twice. His first commission was in<br />

1690– 92 when the I st Duke of Montagu, former British<br />

Ambassador to France, commissioned him to paint the<br />

Triumph of Minerva among the Assembly of the Gods as<br />

the ceiling decoration for his Grand Salon in Montagu House,<br />

Bloomsbury, also now destroyed. 3 There is a sketch for the<br />

Crozat ceiling in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, and a<br />

related sketch (Fig. 1), both of which show Minerva seated<br />

on clouds with Mercury at her side, Apollo behind her and<br />

Diana reclining to her right below. 4 It seems possible therefore<br />

that our drawing belongs to the early stage in the design<br />

of this project. His use of trois crayons to create light<br />

and volume anticipates the graphic style of Watteau who<br />

lived with de la Fosse in Crozat’s residence from 1706. It<br />

was on the advice of de la Fosse that Watteau was commissioned<br />

to paint the Four Seasons for Crozat’s dining room.<br />

Charles de la Fosse was the most important decorative<br />

painter in France at the end of the seventeenth century.<br />

His two most famous projects were those for the Dome<br />

des Invalides and the Chapel and Grands Appartements<br />

at Versailles. Clémentine Gustin-Gomez suggests that this<br />

elegant sheet with its artfully arranged figure studies of<br />

gods and goddesses sitting or kneeling on the clouds is a<br />

design for a grandiose decorative scheme. The goddess<br />

Minerva with her helmet and lance is prominent top left<br />

with a male figure at her side, perhaps Mercury. Edith<br />

Standen suggested that the figure bottom right might<br />

represent Diana as she is closely related to the goddess in<br />

de la Fosse’s Rest of Diana in the Hermitage although<br />

in that painting the figure is reversed. 1 Since none of the<br />

figures except for Minerva bear their attributes, they cannot<br />

be identified with certainty.<br />

According to Gustin-Gomez, Colin Bailey proposed that<br />

our drawing could be related to de la Fosse’s Birth of Minerva,<br />

painted in the vault of the Grande Galerie in Pierre<br />

Fig. 1<br />

38

LUDOVICO GIMIGNANI<br />

Rome 1643–1697 Zagarolo<br />

15<br />

GOD THE FATHER AND THE ALTAR OF<br />

THE EUCHARIST, WITH SAINT MICHAEL<br />

VANQUISHING SATAN BELOW<br />

Red chalk, red and brown wash, heightened with white<br />

380 × 280 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Private collection, Paris<br />

This large drawing, executed in a mixed technique of<br />

brush with red and brown wash, heightened with white<br />

over red chalk, could well be a design for an oval altarpiece.<br />

The unusual oval shape makes a connection with a<br />

ceiling fresco in a side chapel somewhat less likely. It is<br />

possible, however, that the drawing is a study for a ceiling<br />

fresco in a sacristy. No such work by Lodovico Gimignani,<br />

however, has thus far come to light. Yet his extant depictions<br />

of Saint Michael fighting devils show angels and<br />

demons in extremely similar poses. One might think, for<br />

instance, of Lodovico’s altarpiece of Saint Michael in the<br />

church of S. Andrea delle Fratte, Rome, which he provided<br />

with several paintings in the 1680s. A quick sketch in<br />

the Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica, Rome, belongs in this<br />

context.<br />

Its close affinity in style and technique to two drawings<br />

given to Lodovico in the British Museum is evident (Fig. 1),<br />

even though the use of red chalk and red-brown wash is<br />

rather infrequent in Gimignani’s drawing oeuvre. The<br />

majority of his drawings preserved at the Istituto Nazionale<br />

per la Grafica in Rome are in black chalk and, if wash is applied,<br />

it is mostly grey. But the forcefully applied white<br />

gouache, which is here somewhat reminiscent of Passeri’s<br />

technique, can be found on occasion, such as in the context<br />

of his drawings and paintings for S. Silvestro in Capite<br />

in Rome. These are mostly drawings from his most produc -<br />

tive period, during which he executed numerous private<br />

paintings commissions as well as frescoes for churches<br />

and houses in Rome, before his unexpected death put a<br />

sudden end to all his artistic activity.<br />

URSULA VERENA FISCHER PACE<br />

Fig. 1<br />

40

NICCOLÒ RICCIOLINI<br />

Rome 1687–1772 Rome<br />

16<br />

THE VESTAL VIRGIN TUCCIA<br />

PROVING HER INNOCENCE<br />

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, grey and brown wash,<br />

with brown ink framing lines<br />

370 × 510 mm<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

Private collection, Paris<br />

Considered by Johann Joachim Winckelmann a “painter<br />

of great talent and highly gifted,” and by the historian Luigi<br />

Lanzi a “good draughtsman,” Niccolò Ricciolini was a<br />

leading member of a late Roman baroque dynasty of<br />

painters. 1 Among the most highly esteemed artists of his<br />

generation, he worked also as an engraver, sculptor, and<br />

architectural scholar. He was the son and pupil of the<br />

painter Michelangelo Ricciolini, and father of Michelangelo<br />

Maria Ricciolini. He received numerous prestigious commissions<br />

in Rome, most notably for St. Peter’s, as well as in<br />

various other locations in Lazio, Tuscany, Umbria, and the<br />

Marches. His patrons included both religious orders and<br />

the leading families of the period, such as the Albani,<br />

Barberini, Colonna, Orsini, and Ottoboni families. In<br />

1702– 03, aged 15–16, he won three competitions at the<br />

Accademia di San Luca, testifying to his precocious talent<br />

as a draughtsman. In 1719 he was elected a Virtuoso at<br />

the Pantheon and in 1721 an Academician of San Luca.<br />

Fig. 1<br />

His relatively rare drawings are preserved in several major<br />

public collections, such as the Uffizi, the British Museum,<br />

Windsor Castle, the Accademia di San Luca, the Istituto<br />

Nazionale per la Grafica, Rome, the Metropolitan Museum<br />

of Art, and the Martin-von-Wagner-Museum at Würz -<br />

burg. 2 While some of the drawings in these collections are<br />

connected with known paintings by the artist others have<br />

been attributed to him on the basis of style. The present<br />

drawing belongs to the latter category and will be<br />

published by the present author in a forthcoming essay<br />

dedicated to Ricciolini’s drawings.<br />

Ricciolini’s pen style is fairly easily recognizable, most<br />

notably by its segmented outlines, clearly visible in the<br />

figures and draperies, the faces, objects and architectural<br />

elements. This characteristic technique is complemented,<br />

more in the non-religious than religious subjects, by<br />

strongly Cortonesque compositions, which, however,<br />

neither betray the classical and enduring influence of<br />

Carlo Maratti, the teacher of the father Michelangelo,<br />

something that is evident in all of Niccolò’s works.<br />

Different from his early works preserved at the Accademia<br />

di San Luca, this drawing belongs to the artist’s maturity,<br />

datable to the 1760s or 1770s. This is evident by comparison<br />

with two drawings from the Uffizi, thus far unpublished,<br />

signed and dated 1763 and 1764, respectively, one<br />

of which is a study for the painting in the Sala dei Fasti<br />

Colonna in the Palazzo Barberini, Rome. 3 The anatomies<br />

and shape of the figures, their gestures and expressions,<br />

and the manner in which they are arranged correspond<br />

closely with those in this drawing. The broken, and often<br />

reinforced, pen lines, the shadows in wash and the fine<br />

under drawing in black chalk reveal the same hand, as<br />

does the careful disposition of the figures and the overall<br />

composition, which appears crowded but where every<br />

element supports the narrative. Another closely related<br />

sheet is at Würzburg, showing Cincinnatus leaving the<br />

3<br />

42

NICCOLÒ RICCIOLINI<br />

3<br />

16<br />

Plow for the Roman dictatorship (Fig. 1). 4 The composition<br />

of the present drawing also recalls those of other well<br />

known paintings by the artist, such as the Resurrection<br />

of Lazarus, today at the Museo del Barocco Romano at<br />

Ariccia. 5<br />

In this drawing, Ricciolini tried his hand at a relatively rare<br />

though not unknown subject in Italian Renaissance and<br />

Baroque art, with extant depictions by Mantegna and<br />

Polidoro da Caravaggio, up to Maratti and his contemporary<br />

Trevisani, who exerted some influence over our artist<br />

and who was also the uncle of Ricciolini’s wife. The legendary<br />

Tuccia, priestess of Vesta the goddess of the<br />

hearth, home and family, was accused of breaking her vow<br />

of chastity. Her story is reported by various Roman authors,<br />

among which were Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Livy,<br />

Valerius Maximus, Pliny, and Plutarch. The punishment for<br />

this type of crime for the Vestal virgins, who could not be<br />

put to death by mere human hands, was for them to be<br />