Bryophytes of springs and flushes - 2009 course notes - Plantlife

Bryophytes of springs and flushes - 2009 course notes - Plantlife

Bryophytes of springs and flushes - 2009 course notes - Plantlife

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

LOWER PLANTS AND FUNGI PROJECT - TRAINING DAY<br />

BRYOPHYTES OF SPRINGS AND FLUSHES<br />

COURSE NOTES<br />

written for <strong>Plantlife</strong> Scotl<strong>and</strong> by Gordon Rothero,<br />

Course Leader <strong>and</strong> Consultant Bryologist<br />

April <strong>2009</strong><br />

Date <strong>of</strong> <strong>course</strong>: 15 th / 16th June <strong>2009</strong>, 10.00am – 5.30pm<br />

Venue:<br />

Ben Lawers<br />

Course Leader: Gordon Rothero<br />

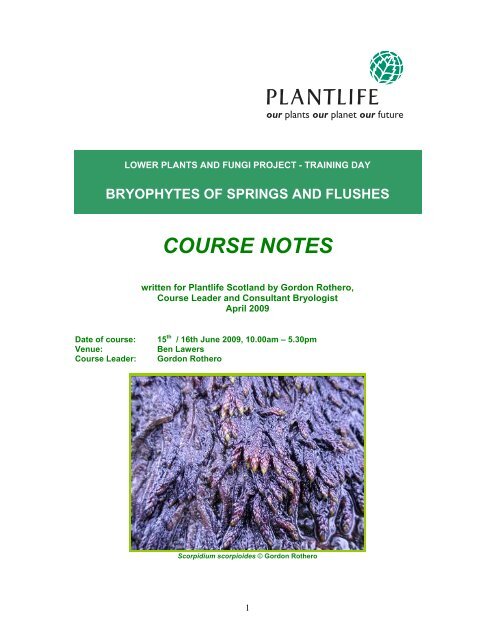

Scorpidium scorpioides © Gordon Rothero<br />

1

BRYOPHYTES OF SPRINGS AND FLUSHES<br />

Springs <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> are an extremely important habitat for bryophytes <strong>and</strong> mosses <strong>and</strong><br />

liverworts <strong>of</strong>ten form a significant proportion <strong>of</strong> the biomass. <strong>Bryophytes</strong> have a significant<br />

presence in at least 12 National Vegetation Classification (NVC)* spring <strong>and</strong> flush<br />

communities <strong>and</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> these correspond to categories on Annex I <strong>of</strong> the Habitats<br />

Directive; the more important <strong>of</strong> these are briefly described below. Spring <strong>and</strong> flush<br />

communities vary widely in species composition, ranging from the acidic, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

extensive, M6 Carex echinata – Sphagnum fallax mires to the strongly calcareous, <strong>and</strong><br />

usually small, M38 Palustriella commutata – Carex nigra <strong>springs</strong>. Springs <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> may<br />

be dominated by just a small number <strong>of</strong> common bryophytes or may have a diverse flora with<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> rare <strong>and</strong> scarce species. There are 41 bryophyte species <strong>of</strong> conservation<br />

interest that have at least some important populations in <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> <strong>and</strong> some <strong>of</strong><br />

these are confined to this habitat; these species are listed with their status in Table 2. Of this<br />

long list, 10 are BAP species, eight are considered Vulnerable or Endangered in the<br />

Bryophyte Red Data Book, four are on Schedule 8 <strong>of</strong> the Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Countryside Act, one is<br />

included in a list <strong>of</strong> the world’s most threatened bryophytes <strong>and</strong> one is listed in the Bern<br />

Convention <strong>and</strong> on Annex IIb <strong>of</strong> the EU Habitats <strong>and</strong> Species Directive.<br />

(*NB The National Vegetation Classification (NVC) is a comprehensive classification <strong>and</strong> description <strong>of</strong> the plant<br />

communities <strong>of</strong> Britain, each systematically named <strong>and</strong> arranged <strong>and</strong> with st<strong>and</strong>ardised descriptions for each.<br />

More details can be seen at http://www.jncc.gov.uk/page-4259 The NVC categories have been used as a<br />

structure for describing species on this <strong>course</strong>).<br />

What are <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> ?<br />

Springs are usually the point source <strong>of</strong> a burn, where the water-table meets the ground<br />

surface, <strong>and</strong> so there is <strong>of</strong>ten a series <strong>of</strong> <strong>springs</strong> across the slope at much the same level,<br />

which, appropriately enough, is called the ‘spring line’. Springs are usually small <strong>and</strong> welldefined<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten have a complete cover <strong>of</strong> bryophytes with just scattered flowering plants.<br />

Flushes are areas where the flow <strong>of</strong> ground water is more diffuse, either where the water<br />

table reaches the surface or where or where water flows widely over the surface <strong>of</strong> saturated<br />

ground rather than in a well-defined channel. They can be areas <strong>of</strong> open, stony ground with<br />

only a sparse plant cover or have a complete <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten dense cover <strong>of</strong> vascular plants,<br />

usually sedges or rushes, with the bryophytes forming a ‘ground layer’ under this ‘canopy’.<br />

We tend to think <strong>of</strong> both <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> as particularly associated with open habitat in<br />

the upl<strong>and</strong> areas <strong>of</strong> Scotl<strong>and</strong> but they can occur right down to sea level <strong>and</strong> under a<br />

woodl<strong>and</strong> canopy, where they seem to be close to M36, but obviously the species<br />

composition will tend to differ markedly in each case.<br />

The vegetation associated with the various <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> is determined by the physical<br />

character <strong>of</strong> the habitat, particularly the temperature <strong>and</strong> the mineral content <strong>of</strong> the water. In<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> species, the NVC communities M10, M11 <strong>and</strong> M12 where the<br />

groundwater is moderately or strongly calcareous are by far the most important but the icy,<br />

nutrient-poor meltwater <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> M31, M33 <strong>and</strong> the higher level M32 st<strong>and</strong>s are<br />

also <strong>of</strong> conservation concern as they are so restricted in their distribution. However it is<br />

interesting <strong>and</strong> perhaps instructive to note that the BAP species are scattered through a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> flush types, with the most threatened <strong>of</strong> them at relatively low level.<br />

2

Threats<br />

Climate change<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> flush communities, particularly those with Pohlia wahlenbergii var. glacialis <strong>and</strong><br />

Pohlia ludwigii which are dependant on the cold water associated with areas <strong>of</strong> late snow-lie<br />

are clearly under threat if the pattern <strong>of</strong> snow accumulation <strong>and</strong> persistence changes. There<br />

is good evidence that the pattern <strong>and</strong> duration <strong>of</strong> snow lie in Scotl<strong>and</strong> is already changing.<br />

Over time there may well be other changes as part <strong>of</strong> a complex shift in plant communities<br />

<strong>and</strong> their spatial distribution as a result <strong>of</strong> what will probably be a warmer <strong>and</strong> wetter climate.<br />

Pollution<br />

Though most <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> are well away from the sources <strong>of</strong> pollution, the vegetation<br />

is still under threat from sulphur <strong>and</strong> nitrogen deposition which is enhanced by the heavy<br />

rainfall <strong>and</strong> deposition in droplets <strong>of</strong> mist when the hills are cloud-capped. Mosses <strong>and</strong><br />

liverworts are particularly susceptible to this kind <strong>of</strong> pollution. A particular problem in the<br />

higher hills is the concentration <strong>of</strong> pollutants in the snowpack, built up over the winter, which<br />

can then be suddenly released through a rapid thaw, the ‘acid flush’ which can kill fish<br />

downstream. The long-term effects <strong>of</strong> this pollution are unclear but it must have some effect<br />

on the bryophytes which have no protective cuticle <strong>and</strong> so absorb water <strong>and</strong> pollutants<br />

directly into the cells <strong>of</strong> the leaf.<br />

Drainage<br />

By their nature, <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> occur in wet places <strong>and</strong> so have always been threatened<br />

by changes in the local hydrology. The most obvious threat is by drainage, gripping an area<br />

to improve it for grazing or the planting <strong>of</strong> trees. The more extensive <strong>flushes</strong> are <strong>of</strong>ten the<br />

main casualty <strong>of</strong> this form <strong>of</strong> management through direct damage <strong>and</strong> a prolonged drying out<br />

<strong>of</strong> the areas affected. It is quite remarkable how much <strong>of</strong> this went on, presumably when<br />

grants were available, <strong>and</strong> it is not unusual to come across patterns <strong>of</strong> ditches in quite<br />

remote upl<strong>and</strong> areas.<br />

This era has now passed <strong>and</strong> gripping in upl<strong>and</strong> areas is rare but it this threat has been<br />

replaced by that from the changes in hydrology that occur as a result <strong>of</strong> the construction <strong>of</strong><br />

the infrastructure necessary to service windfarms. All windfarms require service roads to<br />

each turbine <strong>and</strong> these, plus the associated ditching <strong>and</strong> drainage will change the hydrology<br />

<strong>of</strong> the affected area as well as having a more direct local effect. The only Scottish site for the<br />

BAP liverwort Pallavicinia lyellii, in flushed Molinea caerulea grassl<strong>and</strong>, is now part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

huge Eaglesham windfarm. A planned windfarm in the Ochils will affect a large population <strong>of</strong><br />

Hamatocaulis vernicosus (Bern Convention, EU Directive Annex IIb, Schedule 8 WCA).<br />

Apart from the <strong>flushes</strong> destroyed by the construction process, it is not known what the effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> the changes in the hydrology in the <strong>flushes</strong> might be <strong>and</strong> it is unlikely that any monitoring<br />

work has formed part <strong>of</strong> the mitigation.<br />

Forestry<br />

In the past, blanket aforestation has destroyed <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> over a vast swathe <strong>of</strong><br />

Scotl<strong>and</strong> but particularly so in the south <strong>and</strong> west. In Cowal, Argyll, for example, above the<br />

valley bottom, there are very few slopes without commercial plantations, many well into their<br />

second rotation. The process <strong>of</strong> blanket aforestation <strong>of</strong> open hill l<strong>and</strong> with commercial<br />

conifers has diminished considerably in recent years but <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong>, being small<br />

scale features, are still vulnerable.<br />

One, rather ironic, threat is from the commendable zeal for the expansion <strong>of</strong> broadleaf <strong>and</strong><br />

native Scots pine woodl<strong>and</strong>, where the drive to increase woodl<strong>and</strong> cover tends to overpower<br />

the consideration <strong>of</strong> diverse small-scale habitats like <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong>. On Rhum, such<br />

planting was probably responsible for the demise <strong>of</strong> Hamatocaulis vernicosus in its one site<br />

on the isl<strong>and</strong>. Some cr<strong>of</strong>ting woodl<strong>and</strong> schemes in Sutherl<strong>and</strong> where sites have been<br />

scarified before planting are also poorly designed in this respect. Even exclosures to<br />

3

encourage natural regeneration by excluding grazing animals can be bad news for <strong>flushes</strong> as<br />

the bryophytes can be overwhelmed by the growth <strong>of</strong> coarse vegetation or dense<br />

regeneration <strong>of</strong> trees. There is a good (or should that be bad) example <strong>of</strong> this on the<br />

Morrone NNR, where dense birch regeneration in exclosures is changing the nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

extensive <strong>flushes</strong> associated with the limestone there.<br />

Trampling by livestock<br />

Springs <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> are attractive to livestock as they <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>of</strong>fer localised patches <strong>of</strong> more<br />

lush vegetation <strong>and</strong> a source <strong>of</strong> water during dry spells. Certain <strong>flushes</strong> seem to become<br />

popular <strong>and</strong> attract large numbers <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>and</strong> can be badly poached. The damage by<br />

poaching can look dramatic but as long as it does not persist for long periods, the bryophytes<br />

can recover <strong>and</strong> some may even benefit. The obvious problem lies in those sites with a<br />

small population <strong>of</strong> a particularly vulnerable species.<br />

Management recommendations<br />

Climate change <strong>and</strong> atmospheric pollution<br />

The problems that face <strong>flushes</strong> on the higher hills are global in nature <strong>and</strong> regrettably are not<br />

within the scope <strong>of</strong> the scale <strong>of</strong> management to which we might aspire!<br />

Survey <strong>and</strong> assessment<br />

Perhaps the most important management tool for the well-being <strong>of</strong> these diverse habitats is<br />

to recognise both their presence <strong>and</strong> their local, <strong>and</strong> sometimes national, importance. This is<br />

not always easy to achieve for features which are usually small in comparison to the area<br />

being ‘managed’. Where large-scale changes to an area are being considered, be it for<br />

woodl<strong>and</strong> regeneration or windfarms, it is important that any prior assessment <strong>of</strong> the site is<br />

competent to identify the conservation value <strong>of</strong> the bryophyte-rich <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> that<br />

may occur.<br />

Drainage<br />

To be effective, drainage has to target those areas where water movement can be enhanced<br />

<strong>and</strong> by definition this means that the lines <strong>of</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> will be preferentially affected either by<br />

drains running through them or water channelled into them. This means that if an area has<br />

to be drained then any <strong>flushes</strong> will almost certainly be lost or at least radically altered.<br />

Where the drainage is designed to protect installations or access tracks, it should be possible<br />

to design this so as to have minimum impact on important spring <strong>and</strong> flush sites. At a<br />

smaller scale it should be possible to avoid having ditches <strong>and</strong> culverts emptying into existing<br />

<strong>flushes</strong>.<br />

Forestry<br />

Again, the best possibility <strong>of</strong> protecting <strong>flushes</strong> is at the design stage. It has to be accepted<br />

that if the prime objective is to establish a woodl<strong>and</strong>, then not all open <strong>flushes</strong> can be<br />

preserved. However, if there are <strong>flushes</strong> <strong>of</strong> conservation interest on the site some effort<br />

should be made to limit disturbance to these sites. Not only does this mean not planting<br />

through the flush but also retaining an open buffer zone around the flush so that shading <strong>and</strong><br />

litter fall are also limited. It is probable that, over time, the nature <strong>of</strong> the run-<strong>of</strong>f will alter <strong>and</strong><br />

even those <strong>flushes</strong> that are undisturbed will change in nature but may still have interesting<br />

bryophytes.<br />

Poaching by livestock <strong>and</strong> deer<br />

Where poaching is limited in both extent <strong>and</strong> duration, its effects on the flush vegetation are<br />

likely to be moderate given that these are dynamic habitats. Poaching may even be<br />

beneficial in restricting the growth <strong>of</strong> rapidly growing, carpet-forming, vascular plants like<br />

Montia fontana <strong>and</strong> Chrysosplenium oppositifolium. Where stocking levels are consistently<br />

high it is likely that most <strong>flushes</strong> will have been altered by eutrophication as well as poaching,<br />

4

<strong>of</strong>ten having only large st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> common, robust species. It is only where there is a spring<br />

or flush with a species <strong>of</strong> conservation concern that the level <strong>of</strong> poaching needs to be<br />

monitored, <strong>and</strong> again, knowledge <strong>of</strong> the site is all-important.<br />

OUTLINE OF BRYOPHYTE SPECIES OF SPRINGS AND FLUSHES<br />

NVC communities that have strong elements <strong>of</strong> flushing <strong>and</strong> where bryophytes are an<br />

important constituent <strong>of</strong> the vegetation:<br />

These descriptions are, <strong>of</strong> necessity, very brief <strong>and</strong> the NVC volumes (Rodwell, 1991) <strong>and</strong><br />

Averis et al (2004) have a lot more detail. Boundaries <strong>of</strong> spring <strong>and</strong> flush vegetation can be<br />

very sharp but st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong>ten contain a mix <strong>of</strong> flush types; for instance, M10 <strong>and</strong> M11 <strong>flushes</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>ten have a Palustriella commutata spring at their head <strong>and</strong> M6 <strong>flushes</strong> may well contain a<br />

line <strong>of</strong> M32 Philonotis fontana within them.<br />

M6 Carex echinata – Sphagnum fallax<br />

mire<br />

Rather dull but <strong>of</strong>ten very extensive in the<br />

west <strong>of</strong> Scotl<strong>and</strong> with a sward <strong>of</strong> sedges or<br />

rushes over species <strong>of</strong> Sphagnum. The<br />

most prominent <strong>and</strong> extensive are M6c <strong>and</strong> d<br />

with Juncus effusus <strong>and</strong> Juncus acutiflorus<br />

dominant over lawns <strong>of</strong> Sphagnum palustre<br />

<strong>and</strong> Sphagnum fallax with some Sphagnum<br />

denticulatum in the wettest areas. The<br />

groundwater is rather acidic <strong>and</strong> bryophyte<br />

diversity is usually very low. Richer st<strong>and</strong>s<br />

with fewer Sphagna <strong>and</strong> much Calliergonella<br />

cuspidata are probably closer to M23 Rush pasture.<br />

M7 Carex curta – Sphagnum russowii mire<br />

The upl<strong>and</strong> extension <strong>of</strong> M6 but much less extensive, <strong>of</strong>ten in b<strong>and</strong>s below <strong>springs</strong> in areas<br />

where snow lies moderately late <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten associated with upl<strong>and</strong> plateau areas. The<br />

important bryophyte components apart from Sphagnum russowii are two nationally scarce<br />

species Sphagnum riparium (illustrated) <strong>and</strong> Sphagnum lindbergii.<br />

5

M10 Carex dioica – Pinguicula vulgaris mire <strong>and</strong> M11 Carex viridula subsp. oedocarpa<br />

– Saxifrage aizoides mire<br />

Most calcareous <strong>flushes</strong> in the hills belong to these two communities <strong>and</strong> the two can be<br />

difficult to separate. Both can occur as open, stony <strong>flushes</strong> but M10 generally has a more<br />

prominent vascular plant cover. The bryophytes are <strong>of</strong>ten the same in both communities;<br />

most consistent in the open stony areas are common species like Scorpidium scorpioides,<br />

Drepanocladus revolvens, Blindia acuta, Aneura pinguis (below bottom right), Campylium<br />

stellatum var stellatum, Ctenidium molluscum <strong>and</strong> occasionally Pseudocalliergon trifarium<br />

(below bottom left). The hummocks <strong>and</strong> margins <strong>of</strong> the <strong>flushes</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten have a greater diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> species including rare <strong>and</strong> scarce species including Meesia uliginosa (top right) . The<br />

BAP species Tayloria lingulata is restricted to these two flush communities <strong>and</strong> M12, usually<br />

on hummocks within the flush. Another BAP species, Splachnum vasculosum, can form long<br />

st<strong>and</strong>s along the margins <strong>of</strong> the flush.<br />

M12 Carex saxatilis mire<br />

This uncommon flush type usually has a more complete <strong>and</strong> taller cover than M10 <strong>and</strong> M11<br />

with Carex saxatilis dominant but usually with other sedges. It is <strong>of</strong>ten not as strongly<br />

calcareous as the most diverse M10 <strong>and</strong> M11 <strong>flushes</strong> <strong>and</strong> is usually above 600m. The<br />

bryophytes are similar to M10 <strong>and</strong> M11 but <strong>of</strong>ten less diverse but a number <strong>of</strong> rarities do<br />

occur here including Tayloria lingulata.<br />

6

M31 Anthelia julacea – Sphagnum denticulatum spring<br />

A high altitude community with cold <strong>and</strong> acid groundwater <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten associated with<br />

snowbed vegetation. The grey mats <strong>of</strong> Anthelia julacea are easily recognised <strong>and</strong><br />

Sphagnum denticulatum is usually common but there is always an admixture <strong>of</strong> other<br />

species particularly Scapania undulata, Scapania uliginosa <strong>and</strong> occasionally the rare<br />

Scapania paludosa.<br />

M32 Philonotis fontana – Saxifraga stellaris spring<br />

This is the most common <strong>of</strong> the hill <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> <strong>and</strong> is very variable, ranging from<br />

st<strong>and</strong>s that are moderately calcareous (where Philonotis fontana may be replaced by<br />

7

Philonotis calcarea) to moderately acidic. The common feature is the <strong>of</strong>ten extensive mats <strong>of</strong><br />

Philonotis fontana usually with a mix <strong>of</strong> other bryophytes including Dichodontium palustris,<br />

Brachythecium rivulare, Bryum pseudotriquetrum, Scapania undulata <strong>and</strong> on the margins<br />

Sphagnum denticulatum. Higher st<strong>and</strong>s may also have Bryum weigelii (the pink in the flush<br />

above bottom right), Philonotis seriata <strong>and</strong> Scapania uliginosa (above bottom left). Lower<br />

down many flushed areas have st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Philonotis fontana, <strong>of</strong>ten with the typical associates<br />

but the vascular plant component is usually different, <strong>of</strong>ten Montia fontana or<br />

Chrysosplenium oppositifolium.<br />

M33 Pohlia wahlenbergii var. glacialis spring<br />

This is the arctic-montane equivalent <strong>of</strong> the<br />

M32 flush characterised by large pure st<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>of</strong> Pohlia wahlenbergii var. glacialis, which<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten visible from some distance.<br />

Associated bryophyte species are <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

limited but include Philonotis fontana, Pohlia<br />

ludwigii, Scapania uliginosa, Scapania<br />

undulata <strong>and</strong> Marsupella sphacelata.<br />

M37 Palustriella commutata – Festuca rubra spring <strong>and</strong> M38 Palustriella commutata –<br />

Carex nigra spring<br />

These are the ‘brown moss’ <strong>springs</strong> characterised by large st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Palustriella commutata<br />

or Palustriella falcata, <strong>of</strong>ten to the exclusion <strong>of</strong> other bryophytes. They <strong>of</strong>ten occur as small<br />

patches at the spring-head <strong>of</strong> other calcareous flush types but in limestone areas can form<br />

extensive st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong>ten with some tufa formation.<br />

8

M36 Lowl<strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong><br />

There are a variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> on lower ground <strong>and</strong> in woodl<strong>and</strong> which may have some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

species <strong>of</strong> the upl<strong>and</strong> communities, particularly Aneura pinguis, Calliergonella cuspidata,<br />

Philonotis fontana, Dichodontium palustris <strong>and</strong> Brachythecium rivulare but also containing a<br />

range <strong>of</strong> other species. The base status <strong>of</strong> the water <strong>and</strong> shading are both important. In<br />

woodl<strong>and</strong> the <strong>flushes</strong> can range from those dominated by Sphagnum squarrosum to more<br />

diverse swards with Plagiomnium elatum <strong>and</strong> Trichocolea tomentella.<br />

9

The species<br />

Table 1. Bryophyte species <strong>of</strong> conservation interest with at least some important<br />

populations in <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong>.<br />

Species BAP RDB status National WCA Europe<br />

status<br />

Amblyodon dealbatus<br />

Scarce<br />

Andreaea nivalis BAP Near threatened Scarce<br />

Aplodon wormskjoldii BAP Critically endangered Rare<br />

Barbilophozia quadriloba Near threatened Rare<br />

Bryoerythrophyllum BAP Near threatened Rare<br />

caledonicum<br />

Bryum schleicheri var BAP Critically endangered Rare WCA<br />

latifolium<br />

Bryum weigelii<br />

Scarce<br />

Catascopium nigritum<br />

Scarce<br />

Cinclidium stygium<br />

Scarce<br />

Dicranella grevilleana Near threatened Rare<br />

Dicranum undulatum BAP Vulnerable Scarce<br />

Hamatocaulis vernicosus Scarce WCA Bern<br />

Convention,<br />

EU Species<br />

Directive<br />

Harpanthus flotowianus<br />

Scarce<br />

Hygrohypnum molle Vulnerable Rare<br />

Jamesoniella undulifolia BAP Endangered Rare WCA Red list<br />

Leiocolea gilmanii Near threatened Rare<br />

Liochlaena lanceolata BAP Critically endangered Rare<br />

Meesia uliginosa<br />

Scarce<br />

Moerckia hibernica<br />

Scarce<br />

Odontoschisma<br />

Scarce<br />

elongatum<br />

Oncophorus virens<br />

Scarce<br />

Oncophorus wahlenbergii Near threatened Rare<br />

Pallavicinia lyellii BAP Vulnerable Scarce Red list<br />

Palustriella decipiens Near threatened Scarce<br />

Philonotis seriata<br />

Scarce<br />

Plagiomnium medium Near threatened Rare<br />

Pohlia ludwigii<br />

Scarce<br />

Pseudobryum<br />

Scarce<br />

cinclidioides<br />

Pseudocalliergon trifarium<br />

Scarce<br />

Pseudocalliergon<br />

Vulnerable Rare WCA<br />

turgescens<br />

Rhizomnium magnifolium<br />

Scarce<br />

Scapania degenii<br />

Scarce<br />

Scapania paludosa<br />

Rare<br />

Scapania uliginosa<br />

Scarce<br />

Sphagnum lindbergii<br />

Scarce<br />

Sphagnum platyphyllum<br />

Scarce<br />

Sphagnum riparium<br />

Scarce<br />

Splachnum vasculosum BAP Near threatened Scarce<br />

Tayloria lingulata BAP Endangered Rare<br />

Tomenthypnum nitens<br />

Scarce<br />

Tritomaria polita<br />

Scarce<br />

10

Typical flush species<br />

Sphagnum palustre & Sphagnum fallax<br />

These two bog mosses <strong>of</strong>ten dominate the ground layer to the exclusion <strong>of</strong> all else in acid<br />

sedge or rush dominated <strong>flushes</strong> – the M6 community. This floristically rather dull<br />

community is widespread in the W <strong>of</strong> Scotl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Calliergonella cuspidata<br />

Where the ground water is a bit more<br />

productive the Sphagnum species are<br />

much less prominent <strong>and</strong> this moss can be<br />

overwhelmingly dominant under the<br />

rushes.<br />

Philonotis fontana<br />

This is the characteristic species <strong>of</strong> many hill<br />

<strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> where the water is not<br />

base-rich. The rather stiff erect, bright green<br />

stems <strong>and</strong> the <strong>of</strong>ten present, round capsules<br />

make it very easy to recognise. It can form<br />

dense patches, covering the whole spring or<br />

can form patches with the next three<br />

species.<br />

11

Scapania undulata<br />

This common riparian liverwort is also<br />

frequent in acid <strong>flushes</strong> where it is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

reddish-purple in colour. Higher up the hill it<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten occurs with the rather similar Scapania<br />

uliginosa.<br />

Dicranella palustris<br />

The bright yellow-green colour <strong>of</strong> the patches<br />

<strong>of</strong> this moss st<strong>and</strong> out from a distance <strong>and</strong><br />

the reflexed leaves give the shoots a star<br />

shape viewed from above.<br />

Sphagnum denticulatum<br />

This bog-moss is common in a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

habitats but it is characteristic <strong>of</strong> the margins<br />

<strong>of</strong> many M32 <strong>flushes</strong>. In <strong>springs</strong> it almost<br />

always has an ochre-ish tinge <strong>and</strong> this <strong>and</strong><br />

the curved branches mean that it is easily<br />

recognised. Higher up the hill where the<br />

water is colder, it also forms a flush<br />

community (M31) with the next species.<br />

Anthelia julacea<br />

A tiny liverwort but one which <strong>of</strong>ten forms<br />

large swelling cushions in <strong>flushes</strong> over acid,<br />

stony ground in the higher hills, <strong>of</strong>ten below<br />

snow beds. In the M31 community usually<br />

occurs with Scapania undulata <strong>and</strong> Scapania<br />

uliginosa <strong>and</strong> Sphagnum denticulatum. This<br />

community can have very large st<strong>and</strong>s on<br />

easy-angled ground on high plateaux.<br />

12

Pohlia wahlenbergii var. glacialis<br />

The arctic equivalent <strong>of</strong> the M32 Philonotis<br />

fontana flush the M33 community has large<br />

st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> this large moss which probably<br />

holds the record for “a moss identified at a<br />

distance”. The white-green patches are<br />

easily picked out from over a kilometre away<br />

once you know what to look for.<br />

Pohlia ludwigii<br />

Another distinctive moss with arctic affinities<br />

forms large st<strong>and</strong>s in <strong>flushes</strong> over stony<br />

ground in areas <strong>of</strong> late snow-lie.<br />

Scorpidium scorpioides<br />

In more open stony <strong>flushes</strong> on somewhat<br />

more basic ground, this is <strong>of</strong>ten the first<br />

moss to attract the attention, its patches over<br />

the stones looking much like a mass <strong>of</strong><br />

wriggling worms. It usually occurs with the<br />

next two species.<br />

Drepanocladus revolvens<br />

Usually coppery in colour <strong>and</strong> with very<br />

falcate (hooked) leaves <strong>and</strong> shoot-tips, this<br />

moss <strong>of</strong>ten forms large patches at the edge<br />

<strong>of</strong> stony M10 <strong>and</strong> M11 <strong>flushes</strong>.<br />

13

Blindia acuta<br />

In stony <strong>flushes</strong>, this moss is almost<br />

ubiquitous on the surface <strong>of</strong> the stones,<br />

forming a short dark-green turf or scattered<br />

open patches.<br />

Palustriella commutata<br />

Usually forming dense, yellow-brown patches,<br />

sometimes very extensive, in calcareous<br />

<strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten encrusted with<br />

lime.<br />

Hamatocaulis vernicosus<br />

Listed on the Species Directive <strong>and</strong> Berne<br />

Convention, this species is locally frequent in<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> Britain <strong>and</strong> has a number <strong>of</strong> sites<br />

Scotl<strong>and</strong>. It occurs in moderately base-rich<br />

<strong>flushes</strong>, usually in sedge-rich vegetation <strong>and</strong><br />

can form extensive patches. It is easily<br />

confused with other species, particularly<br />

Drepanocladus cossonii.<br />

14

The BAP species<br />

Andreaea nivalis<br />

This h<strong>and</strong>some species is restricted to areas<br />

<strong>of</strong> late snow-lie; usually a species <strong>of</strong> wet<br />

rocks, it also occurs over flushed gravels<br />

where it can form extensive st<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

with Pohlia ludwigii. It is abundant in the<br />

snowbeds <strong>of</strong> the Cairngorms <strong>and</strong> the Ben<br />

Nevis massif but is rare away from these<br />

areas.<br />

Aplodon wormskjoldii<br />

This species is a member <strong>of</strong> the Splachnaceae, the dung mosses but most records in the UK<br />

are from carrion. Not seen in Britain since the 1970s, it may well be extinct. The most recent<br />

record was from a dead sheep in a bog but most records are from carrion in base-rich<br />

<strong>flushes</strong>.<br />

Bryoerythrophyllum caledonicum<br />

A Scottish endemic with scattered sites on<br />

the calcareous schists <strong>of</strong> the central<br />

Highl<strong>and</strong>s with two outlying populations on<br />

Skye <strong>and</strong> Rum. Most sites are on wet silt on<br />

rock ledges but it also occurs in <strong>flushes</strong> on<br />

steep slopes.<br />

Bryum schleicheri var latifolium<br />

A large <strong>and</strong> easily recognisable moss which has always been rare <strong>and</strong> is now seemingly<br />

restricted to one, rather non-descript spring near Stirling.<br />

15

Jamesoniella undulifolia<br />

The one British bryophyte to grace the list <strong>of</strong> the world’s most threatened species. Restricted<br />

to three sites in Scotl<strong>and</strong>, all in <strong>flushes</strong> below basic rocks on low ground by the coast in<br />

Argyll.<br />

Liochlaena lanceolata<br />

Now apparently reduced to one UK site in a flush on the calcareous, Cambrian fucoid beds<br />

near Loch Clare in Torridon. It is not thriving here <strong>and</strong> is perhaps the most threatened<br />

bryophyte in Scotl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Pallavicinia lyellii<br />

Its one Scottish site is on a slope <strong>of</strong> flushed Molinea caerulea grassl<strong>and</strong> – a very nondescript<br />

habitat. The whole site is now part <strong>of</strong> the vast Eaglesham windfarm SW <strong>of</strong> Glasgow<br />

<strong>and</strong> the fate <strong>of</strong> Pallavicinia lyellii is not known<br />

16

Splachnum vasculosum<br />

Another member <strong>of</strong> the Splachnaceae, this<br />

species has declined markedly over the<br />

years. It grows in at least moderately basic<br />

<strong>flushes</strong> <strong>and</strong> can persist in the same site long<br />

after the dung on which it presumably first<br />

grew has gone.<br />

Tayloria lingulata<br />

And yet another member <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Splachnaceae growing on organic material in<br />

calcareous <strong>flushes</strong> <strong>and</strong> limited to a few sites<br />

in the mountains <strong>of</strong> the Central Highl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> only at all frequent on the Ben Lawers<br />

SSSI.<br />

Contacts for further advice <strong>and</strong> support<br />

Dr David Genney, SNH Policy & Advice Officer,<br />

<strong>Bryophytes</strong>, Fungi <strong>and</strong> Lichens<br />

Gordon Rothero, Consultant Bryologist<br />

david.genney@snh.gov.uk<br />

gprothero@aol.com<br />

Matilda Scharsach, Lower Plants & Fungi Officer, matilda.scharsach@plantlife.org.uk<br />

<strong>Plantlife</strong> Scotl<strong>and</strong> Tel 01786 469778<br />

References<br />

Averis AM et al., 2004, An illustrated guide to British upl<strong>and</strong> vegetation, Joint Nature<br />

Conservation Committee, Peterborough.<br />

Averis AM, 2003, Scotl<strong>and</strong>’s living l<strong>and</strong>scapes: <strong>springs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>flushes</strong>, SNH, Inverness.<br />

Rodwell JS (ed), 1991, British Plant Communites Volume 2: Mires <strong>and</strong> Heaths, CUP,<br />

Cambridge.<br />

17