Defamation of Character: How to Avoid It - Writer's Digest

Defamation of Character: How to Avoid It - Writer's Digest

Defamation of Character: How to Avoid It - Writer's Digest

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Defamation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Character</strong>:<br />

<strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Avoid</strong> <strong>It</strong><br />

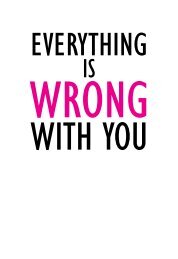

Beware the slinging <strong>of</strong> slang: One<br />

man’s compliment<br />

may be another man’s defamation<br />

suit.<br />

By Amy Cook<br />

If someone called you a “pimp,” would you (a) be insulted—it’s implying<br />

that you sell people in<strong>to</strong> prostitution, for cripes’ sake!—or (b) think you<br />

were being called “cool” or “outrageous”? <strong>How</strong> you answer doesn’t just<br />

tell us whether you’ve celebrated your 25th birthday yet—it could determine<br />

whether you get sued for defamation.<br />

<strong>Defamation</strong> is publishing a false, deroga<strong>to</strong>ry statement about someone<br />

as fact. There are two key elements here: Is the statement able <strong>to</strong> be<br />

proved true or false, and is it insulting? Neither is as simple as it may first<br />

appear.<br />

Common sense says it’s defama<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>to</strong> falsely write that someone is a<br />

pimp. But if you’ve ever watched MTV for a few minutes, you’ve learned<br />

that calling someone a “pimp” can be a compliment. And, whether<br />

you’ve added it <strong>to</strong> your vocabulary or not, choice (b) is an accepted<br />

definition <strong>of</strong> the term in some camps, according <strong>to</strong> SlangSite.com. Evel<br />

Knievel discovered this in his recent defamation lawsuit against ESPN’s<br />

website dedicated <strong>to</strong> extreme sports.<br />

If you write about other people, and especially if you write for the<br />

web or other more fast-paced, cutting-edge publications that use slang,<br />

exaggeration, parody and figurative language, the rules are changing.<br />

You’ll need <strong>to</strong> consider the publication, its target audience, your s<strong>to</strong>ry as<br />

a whole and whether your subject is a public figure.

Target audience<br />

In the Knievel case, ESPN’s website published a pho<strong>to</strong> <strong>of</strong> the daredevil<br />

with his arms around his wife and another woman, with the caption: “Evel<br />

Knievel proves that you’re never <strong>to</strong>o old <strong>to</strong> be a pimp.” The couple said<br />

that the caption was defama<strong>to</strong>ry because it accused Knievel <strong>of</strong> soliciting<br />

prostitution and implied that his wife was a prostitute. The pho<strong>to</strong> was<br />

published on a portion <strong>of</strong> ESPN’s site devoted <strong>to</strong> youth-oriented sports,<br />

such as skateboarding, surfing and mo<strong>to</strong>rcycle racing. Other pho<strong>to</strong> captions<br />

on the site used various slang words and phrases: “share the love,”<br />

“hardcore,” “throwing down a pose,” “put back a few” and “hottie.”<br />

Courts give a lot <strong>of</strong> weight <strong>to</strong> publications’ intended audiences, but<br />

the investigation doesn’t end there. Even though the ESPN site generally<br />

caters <strong>to</strong> teenagers and young adults who understand its captions in a<br />

humorous way, the test is not only who was intended <strong>to</strong> read something,<br />

but also who did read it. Knievel claimed that corporate clients who’d<br />

seen the pho<strong>to</strong>graph and the caption dropped him as a spokesperson.<br />

But, much <strong>to</strong> Knievel’s chagrin, the court ruled against him because—in<br />

context—the audience wasn’t expected <strong>to</strong> believe that he was an actual<br />

pimp.<br />

Fact vs. funny<br />

When using colorful language, can it be “proven” true or false? While<br />

the court dismissed the case brought by Knievel because “pimp” wasn’t<br />

being used in the traditional sense, the dissenting judge pointed out<br />

that the outcome <strong>of</strong> cases like this will vary depending on whether the<br />

court examines for truthfulness in the traditional meaning <strong>of</strong> a word or<br />

phrase, or the slang meaning. In the traditional meaning <strong>of</strong> “pimp,” the<br />

statement can be proven true or false. In the slang sense, it can’t. When<br />

writing your piece, be sure any slang terms are clearly recognizable as<br />

fanciful.<br />

Dissecting intentions<br />

Did you ever have a friend who teased you, <strong>of</strong>ten hurting your feelings,<br />

and then said, “I was just kidding. Can’t you take a joke?” Writers can’t<br />

get away with that. As one judge said, “Jocular intent <strong>of</strong> the publisher<br />

will not relieve him from liability if it is reasonable not <strong>to</strong> understand the<br />

utterance as a joke.”<br />

For instance, a person who was sued for saying a judge was “drunk<br />

on the bench” wasn’t able <strong>to</strong> get away with claiming his statements were<br />

“hyperbole” because he made a factual statement. You can’t dodge a<br />

defamation claim by saying the statement was just your opinion (Stand-

ing Comm. on Discipline <strong>of</strong> the United States Dist. Court v. Yagman,<br />

1995). The court in that case said, “Statements that could reasonably be<br />

unders<strong>to</strong>od as imputing specific criminal or other wrongful acts are not<br />

entitled <strong>to</strong> constitutional protection merely because they are phrased in<br />

the form <strong>of</strong> an opinion.” If you’re stating something as fact, and there’s<br />

little context <strong>to</strong> determine your meaning, a defamation claim becomes<br />

stronger.<br />

Context connotations<br />

Many s<strong>to</strong>ries mix fact and fantasy. If your s<strong>to</strong>ries involve real people, a<br />

court will ask if there are signals that would convey <strong>to</strong> a reasonable person<br />

that it shouldn’t be taken literally. In a recent case, Marshall Mathers,<br />

better known as rapper Eminem, was sued by a private citizen about<br />

whom he’d written a song. The lyrics were about a bully who abused<br />

Mathers when he was a school kid. In Rolling S<strong>to</strong>ne magazine, Mathers<br />

said, “Everything in the song is true.”<br />

While the song contains factual elements that the probable pugilist<br />

admitted <strong>to</strong>, as the rap progresses, it describes highly unlikely incidents.<br />

Mathers claims that the principal joins the bully in “s<strong>to</strong>mping” him on the<br />

head, and that his mother hits him on the head causing his “whole brain”<br />

<strong>to</strong> fall out <strong>of</strong> his skull. The reasonable listener wouldn’t take the song lyrics<br />

literally.<br />

Public figures<br />

<strong>Defamation</strong> charges are <strong>of</strong>ten coupled with a claim <strong>of</strong> intentional infliction<br />

<strong>of</strong> emotional distress. In these cases, it makes a big difference if the<br />

victim is a public or private citizen. Such a case was when Jerry Falwell<br />

sued Hustler magazine for an ad parody the magazine put <strong>to</strong>gether that<br />

depicted Falwell engaging in lewd and outrageous behavior. The jury<br />

said the magazine hadn’t libeled him because the parody “could not<br />

reasonably be unders<strong>to</strong>od as describing actual facts or events.”<br />

With the emotional distress claim, Falwell had <strong>to</strong> meet a higher<br />

burden <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> than a private person would. The First Amendment<br />

prohibits public figures from recovering damages for intentional infliction<br />

<strong>of</strong> emotional distress without also showing that the publication made a<br />

false statement <strong>of</strong> fact that was made with “actual malice.” That is, the<br />

publication must have known that the statement was false or acted with<br />

reckless disregard as <strong>to</strong> its truth. In the Falwell case, the activities the<br />

magazine depicted him doing didn’t really happen, but it wasn’t supposed<br />

<strong>to</strong> be thought true.<br />

The First Amendment and settled law generally are on the writer’s

side. Just remember: When writing about people and using slang or<br />

satire, pick your publication wisely and be sure that the tenor <strong>of</strong> the piece<br />

clues readers in that not everything is <strong>to</strong> be believed. WD<br />

Amy Cook is a Chicago at<strong>to</strong>rney and freelance writer focusing on matters<br />

concerning writers and publishers.