brochure 2012 - Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientÃficas

brochure 2012 - Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientÃficas

brochure 2012 - Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientÃficas

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

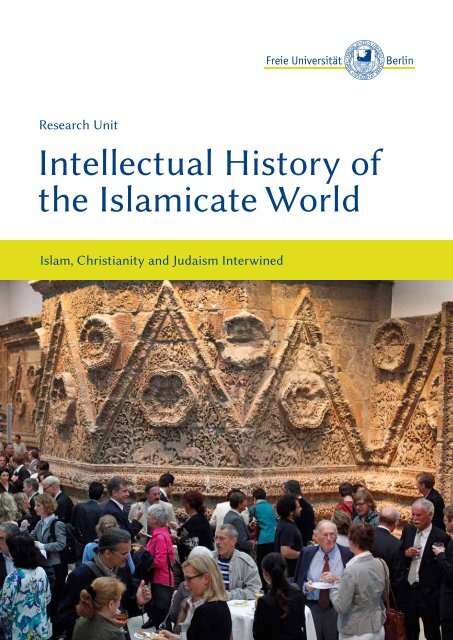

Research Unit<br />

Intellectual History of<br />

the Islamicate World<br />

Islam, Christianity and Judaism Interwined

Research Unit<br />

Intellectual History of<br />

the Islamicate World<br />

Vivantes International Medicine<br />

Medicine – Ma<strong>de</strong> in Germany<br />

Islam, Christianity and Judaism Interwined<br />

Vivantes Netzwerk für Gesundheit GmbH is the biggest state-owned<br />

hospital chain in Germany. Located in Europe’s health capital Berlin,<br />

Vivantes owns 9 Hospitals und 14 nursing homes and treats 500.000<br />

patients p.a. (30% of all patients treated in Berlin). The hospital chain<br />

employs 13,500 members of staff, has 5000 beds and over 40 centres<br />

of excellence. In 2010 sales volume has been 850,000 EUR.<br />

To the international market Vivantes offers 4 products:<br />

1.) Patient Therapy Program: High quality treatment of foreign patients<br />

in Berlin (approx. 1500 patients p.a.) in over 100 medical <strong>de</strong>partments<br />

2.) Visiting Experts – Vivantes experts as guest lecturers and guest<br />

professors abroad<br />

3.) Education Program – Further education of foreign physicians at Vivantes<br />

4.) Consulting & Management in the healthcare sector through Vivantes<br />

International GmbH<br />

Vivantes<br />

Netzwerk für Gesundheit GmbH<br />

Vivantes International Medicine<br />

Am Nordgraben 2<br />

Berlin 13509<br />

Germany<br />

international@vivantes.<strong>de</strong><br />

Tel. +49 (0)30 130 12 1664/<br />

1668/ 1684/ 1685<br />

Fax +49 (0)30 130 12 1082<br />

Cooperation Consulting Our Facilities<br />

Head of Research Unit<br />

Univ.-Prof. Dr. Sabine Schmidtke<br />

www.vivantes-international.com

Contents<br />

Message from the Presi<strong>de</strong>nt 7<br />

Mission and Vision 8<br />

The Team 8<br />

Staff 9<br />

Associated Team Members 10<br />

International and National Cooperations 12<br />

The work of the Research Unit Intellectual History of the Islamicate World and its research areas 14<br />

Executive Summary 14<br />

Detailed Description of the Research Areas and the Current Projects: 14<br />

Critical Avicennism in the Islamic East of the 12th century 14<br />

Muslim and Jewish philosophy intertwined during the 13th through 15th centuries 16<br />

Philosophy in Iran during the Ṣafavid and Qajar Periods 18<br />

Aesthetics 19<br />

The formative period of Mysticism 21<br />

Rationalism and Rational Theology in the Islamicate World 22<br />

Counterreactions 27<br />

The intellectual and religious heritage of Shīʿism (Zaydism and Imamism) 28<br />

Interreligious Controversies 30<br />

Bible in Arabic among Christians, Jews and Muslims 34<br />

Achievements (2003–<strong>2012</strong>) 35

Message from the Presi<strong>de</strong>nt<br />

Thank you for your interest in the Research Unit Intellectual History<br />

of the Islamicate World. One of Freie Universität’s prominent research<br />

centers, the Research Unit combines key features and strengths that<br />

have been <strong>de</strong>cisive for the success of Freie Universität in the recent years:<br />

a clear international orientation, a research program that cuts across traditional<br />

disciplinary boundaries and a commitment that reaches beyond<br />

the aca<strong>de</strong>mic world, true to the founding heritage of Freie Universität.<br />

The Research Unit acts as an umbrella structure for various research<br />

projects, all of which have been very successful in acquiring external<br />

funding, but its objective is not merely an organizational one. Rather, the<br />

overarching intellectual goal is to arrive at a better and more comprehensive<br />

un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of the intellectual history of the Islamicate world,<br />

with particular attention to the medieval, pre-mo<strong>de</strong>rn and early mo<strong>de</strong>rn<br />

periods. The Research Unit employs a new perspective in the pursuit of<br />

this aim: rather than starting out from one of the traditional disciplines –<br />

Islamic Studies, Jewish Studies, Studies of Eastern Christianity – it relies<br />

on an interdisciplinary approach. With this orientation, it takes up - in<br />

many significant ways – a tradition that is at the same time a key object<br />

of its own research: The tradition of exchange between Muslim, Jewish<br />

and Christian scholars that existed in the Islamicate World for centuries.<br />

This intellectual history bears inspiring witness to a rational dialogue between<br />

the three monotheistic religions. An un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of Islam that<br />

sees this dialogue as an integral part of its historical heritage would in<strong>de</strong>ed<br />

be much more than merely an aca<strong>de</strong>mic matter.<br />

Reflecting the research profile of the Research Unit Intellectual History<br />

of the Islamicate World, its team unites scholars from various disciplines,<br />

countries and cultural backgrounds. The extensive international<br />

network, reaching from the Near East to Europe and North America,<br />

makes another vital contribution to its diversity in the aca<strong>de</strong>mic, cultural<br />

and methodolgical sense.<br />

I am convinced that the work of the Research Unit Intellectual History<br />

of the Islamicate World will continue to make groundbreaking<br />

contributions to aca<strong>de</strong>mic research and beyond. In closing, let me also<br />

thank all sponsors who have provi<strong>de</strong>d external funding for the work of<br />

the Research Unit. Needless to say, the work done would not have been<br />

possible without their support.<br />

Peter-André Alt<br />

Presi<strong>de</strong>nt of the Freie Universität Berlin<br />

7

Mission and Vision<br />

In a world in which bor<strong>de</strong>rs increase in significance – be they cultural or<br />

religious, political or economic–aca<strong>de</strong>mic research has the power to <strong>de</strong>monstrate<br />

that intellectual movements disregard any such bor<strong>de</strong>r and<br />

that symbiosis is the norm rather than the exception. This held true<br />

for intellectual movements in one of today’s hottest conflict areas, the<br />

Middle East, cradle of the three monotheistic religions and for more<br />

than two millenia home to major strands of human culture. If we<br />

wish to establish lasting peaceful relations between leading cultures, religions<br />

and political entities, we require above all knowledge about our<br />

own intellectual heritage, about that of others, and about the ways<br />

they intersect. Such knowledge will not only foster mutual respect,<br />

but it will also prevent the spread of i<strong>de</strong>ologically distorted perceptions of<br />

one another. An open mind in research, a readiness to wi<strong>de</strong>n the scope of<br />

scholarly investigation, and a willingness to share its results with a wi<strong>de</strong>r<br />

audience contribute significantly to the shaping of a public opinion<br />

that is less biased and more refined.<br />

Departing from the customary aca<strong>de</strong>mic approach with its (often<br />

exclusive) focus on either Muslim, Jewish or Christian authors and their<br />

writings, the Research Unit Intellectual History of the Islamicate<br />

World at Freie Universität Berlin (formally established in 2011 and exclusively<br />

fun<strong>de</strong>d through third-party funding) is unique in its threedimensional<br />

appreciation of the region’s intellectual history. With<br />

its specific approach it strives to contribute to a peaceful atmosphere<br />

between Muslims and non-Muslims both in the Muslim world and in<br />

the global context. Its members are committed to groundbreaking research<br />

in a variety of aspects of the intellectual history of the Islamicate<br />

world in the medieval, pre-mo<strong>de</strong>rn and early mo<strong>de</strong>rn periods. The results<br />

of their efforts are communicated not only to the scholarly community<br />

worldwi<strong>de</strong> but also to a wi<strong>de</strong>r public in East and West.<br />

The various activities and projects that are now un<strong>de</strong>r the umbrella<br />

of the Research Unit have been fun<strong>de</strong>d since 2003 by a variety of foundations<br />

and institutions, among them the German-Israeli Foundation<br />

(GIF) (2003–06), the Fritz Thyssen Foundation (2005–07, 2010–11), the<br />

Gerda Henkel Foundation (2005, 2006–07, 2008), the Rothschild Foundation<br />

(Yad ha-nadiv) (2006), the European Science Foundation (ESF)<br />

(2007), the European Research Council (ERC) (2008–13), the German<br />

Foreign Office (2009–11), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)<br />

with the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) (2010–13), and<br />

the Einstein Foundation (2010–15).<br />

The Team<br />

♦<br />

The team working at the Research Unit Intellectual History of the<br />

Islamicate World at Freie Universität Berlin not only studies the centuries-old<br />

intellectual symbiosis between Islam, Judaism and Christianity,<br />

it also reflects that symbiosis. The team is international and multireligious,<br />

with an almost equal number of Muslims and non-Muslims,<br />

comprising scholars from various Western countries and from the Middle<br />

East. While all are leading experts in several disciplines of Islamic Studies,<br />

some are also specialized in Christian and Jewish Arabic literature<br />

with proficiency in related languages such as Syriac and Aramaic,<br />

Coptic, Judaeo-Arabic, Hebrew and Persian. Close cooperation among<br />

the staff and the associated team members and an interdisciplinary approach<br />

characterize the work of the Research Unit.<br />

To achieve the maximum outreach within the scholarly community<br />

and the wi<strong>de</strong>r public, the team members publish regularly in a variety<br />

of languages – English, French, German, Arabic, Persian and Hebrew –<br />

on the internet,1 in peer-reviewed journals and in well-established<br />

book series, both in the West and in the Islamic world. Moreover, the<br />

director of the Research Unit is editor-in-chief of the journal Intellectual<br />

History of the Islamicate World, published by Brill, Lei<strong>de</strong>n, that has<br />

recently been launched.2 The Research Unit also publishes three book<br />

series in cooperation with leading aca<strong>de</strong>mic institutions in Iran.3 The aim<br />

is to publish critical editions of important, previously unedited texts and<br />

facsimile editions of particularly valuable manuscripts in the field of the<br />

intellectual history of the Islamicate world and Muslim history. Sixteen<br />

volumes have been published since 2006; another four volumes are currently<br />

in press. Research results and ongoing projects are regularly announced<br />

through the page of the Research Unit,4 its individual members’<br />

homepages and through the various social networks.5 In addition to<br />

publications for an aca<strong>de</strong>mic audience, the Research Unit is also addressing<br />

a wi<strong>de</strong>r audience, through a bi-annual Newsletter (in German),6 a<br />

monthly eNewsletter (English and German) and by organizing regularly<br />

public events aimed at the general public.<br />

Staff<br />

♦<br />

Dr. Hassan Ansari (Research Associate 2005–07, Senior Research Associate<br />

2009–13), PhD Paris 2009 (Ecole Pratique <strong>de</strong>s Hautes Etu<strong>de</strong>s)7<br />

Josephine Gehlhar (Stu<strong>de</strong>nt Assistant since 2009)<br />

Dr. Katja Maria Jung (coordinator of the Research Unit since <strong>2012</strong>), PhD<br />

1 E.g., http://ansari.kateban.com/.<br />

2 www.brill.com/ihiw.<br />

3 Islamic Philosophy, Theology and Mysticism. Facsimiles and Editions (since 2006, edited in<br />

cooperation with the Iranian Institute of Philosophy, Tehran); Classical Muslim Heritage Series<br />

(since 2011, edited in cooperation with Mīrāth-e maktūb, Tehran); Muslim History and Heritage<br />

Series (since 2011, edited in cooperation with Markaz-i Dā‘irat al-ma‘ārif-i buzurg-i islāmī, Teheran).<br />

4 http://www.geschkult.fu-berlin.<strong>de</strong>/e/islamwiss/institut/Intellectual_History_in_the_Islamicate_<br />

World/in<strong>de</strong>x.html.<br />

5 http://www.facebook.com/\#!/pages/Rediscovering-Theological-Rationalism-in-the-Medieval-<br />

World-of-Islam/144710522241165; http://www.facebook.com/pages/Research-Unit-Intellectual-<br />

History-of-the-Islamicate-World/120655678037693; http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/Departments/<br />

Research_Unit_Intellectual_History_of_the_Islamicate_World_Institut_f%C3%BCr_<br />

Islamwissenschaft<br />

6 Cf. http://www.geschkult.fu-berlin.<strong>de</strong>/e/islamwiss/Intellectual_History_in_the_Islamicate_World/<br />

Newsletter/in<strong>de</strong>x.html.<br />

7 http://ansari.kateban.com/.<br />

8 9

Munich 2010<br />

Dr. Lukas Muehlethaler (Senior Research Associate, 2009–13), PhD Yale<br />

20108<br />

Jonas Müller-Laackmann (Stu<strong>de</strong>nt Assistant since <strong>2012</strong>)<br />

Samir Mahmoud (Senior Research Associate since <strong>2012</strong>)<br />

Prof. Sabine Schmidtke (Founding Director of the Research unit), DPhil<br />

Oxford 1990, Professor at Freie Universität Berlin since 20029<br />

Gregor Schwarb (Research Associate 2005–07, Senior Research Associate<br />

2009–13), former Aca<strong>de</strong>mic Director of the Centre for the Study of<br />

Muslim-Jewish Relations, Cambridge10<br />

Dr. <strong>de</strong>s. Jan Thiele (Senior Research Associate, <strong>2012</strong>–13)11<br />

♦<br />

Associated Team Members<br />

Dr. Michael Ebstein (Rothschild Fellow), PhD The Hebrew University of<br />

Jerusalem 201112<br />

Dennis Halft OP, PhD candidate Institute of Islamic Studies, Freie Universität<br />

Berlin13<br />

Prof. Omar Hamdan, Professor of Qurʾānic Studies, Eberhard Karls-Universität<br />

Tübingen14<br />

Prof. Wilferd Ma<strong>de</strong>lung, Laudian Professor of Arabic (Emeritus), University<br />

of Oxford<br />

Damaris Pottek, PhD candidate Institute of Islamic Studies, Freie Universität<br />

Berlin15<br />

Dr. Reza Pourjavady, PhD Freie Universität Berlin 2008, currently Research<br />

Associate, McGill University, Montreal, Institute of Islamic Studies16<br />

Ahmad-Reza Rahimi-Riseh, PhD candidate Institute of Islamic Studies,<br />

Freie Universität Berlin17<br />

Dr. Abdurrahman al-Salimi, PhD Durham 2001 (Ministry of Endowments<br />

and Religious Affairs, Oman)<br />

Prof. A<strong>de</strong>l Y. Sidarus, Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies (Emeritus),<br />

University of Evora, Portugal<br />

8 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/LukasMuehlethaler.<br />

9 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/SabineSchmidtke.<br />

10 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/GregorSchwarb.<br />

11 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/JanThiele.<br />

12 http://huji.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/MichaelEbstein<br />

13 http://www.institut-chenu.eu/in<strong>de</strong>x.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=146&Itemid=95.<br />

14 http://www.uni-tuebingen.<strong>de</strong>/einrichtungen/verwaltung-<strong>de</strong>zernate/i-forschung-strategie-undrecht/zentrum-fuer-islamische-theologie.html.<br />

15 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/TamarIs.<br />

16 http://mcgill.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/RezaPourjavady.<br />

17 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/AhmadRezaRahimiRiseh.<br />

10 11

Prof. Sarah Stroumsa, The Alice and Jack Ormut Professor of Arabic<br />

Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, recipient of a Humboldt Research<br />

Award (2011/12)18<br />

Dr. Sophia Vasalou, PhD Cambridge 2006<br />

Dr. Ronny Vollandt, DPhil Cambridge (UK) 2011, IRHT, Section Hébraïque,<br />

CNRS Paris19<br />

Zeus Wellnhofer, PhD candidate Institute of Islamic Studies, Freie Universität<br />

Berlin20<br />

Eva-Maria Zeis, PhD candidate Institute of Islamic Studies, Freie Universität<br />

Berlin21<br />

International and National Cooperations<br />

♦<br />

The team members of the Research Unit Intellectual History of the<br />

Islamicate World have excellent working relations with a variety of aca<strong>de</strong>mic<br />

institutions and scholars in the Middle East, in Europe and the<br />

US. In Turkey, long-standing relations have been established with scholars<br />

working on related topics at Yıldız Technical University, Department<br />

of Humanities and Social Sciences (Prof. M. Sait Özervarli) and at ISAM<br />

Center for Islamic Studies and Marmara Unversity (Prof. Osman Gazi<br />

Özgü<strong>de</strong>nli, Dr. Harun Anay22), all in Istanbul, and at Uludağ Üniversitesi<br />

İlahiyat Fakültesi in Bursa (Dr. Kadir Gömbeyaz23, Dr. Veysel Kaya24).<br />

In Yemen, the team members are working in close cooperation with<br />

the Imām Zayd b. ʿAlī Cultural Foundation (IZbACF) / Muʾassasat al-<br />

Imām Zayd b. ʿAlī al-thaqāfiyya, Ṣanʿāʾ.25 In Iran, the Dāʾirat al-maʿārif-i<br />

buzurg-i islāmī26 and the Written Heritage Research Centre27, Tehran,<br />

should be mentioned. In Uzbekistan, the Research Unit is cooperating<br />

with the al-Biruni Institute of Oriental Studies of the Aca<strong>de</strong>my of Sciences<br />

of Uzbekistan. Good working contacts with the King Faisal Centre<br />

for Research and Islamic Studies28 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and the<br />

Jumʿat al-Mājid Reseach Center in Dubai29 have been established over<br />

the past years. The Research Unit is also closely collaborating with the<br />

joint Israeli-Palestinian research project Intellectual encounters: Phi-<br />

losophy and Science in the World of Medieval Islam30 in Jerusalem/al-<br />

Quds, with Prof. Sara Sviri, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the<br />

Ben Zvi Institute in Jerusalem. At Tel Aviv University, the Research Unit<br />

is collaborating with Dr. Camilla Adang31 and Prof. Meira Polliack32 on a<br />

research project The Bible in Arabic among Jews, Christians and Muslims.<br />

The members of the Research Unit are also cooperating with the Institute<br />

of Samaritan Studies, Holon, Israel (Binyamin Tsedaka).<br />

In the West, the Research Unit is closely cooperating with the Institute of<br />

Islamic Studies at McGill University in Montreal where Prof. Robert Wisnovsky<br />

and Prof. Jamil Ragep have initiated “The Post-classical Islamic<br />

Philosophy Database Initiative” (PIPDI),33 with Prof. Alexan<strong>de</strong>r Treiger34<br />

of Dalhousie and his discussion group “Arabic Bible”, with Prof. Asad<br />

Q. Ahmed of Washington University in St. Louis, as well as Prof. Ahmet<br />

T. Karamustafa and Prof. Jon McGinnis of the University of Missouri,<br />

who coordinate the Mellon Sawyer Seminar “Graeco-Arabic Rationalism<br />

in Islamic Traditionalism: The Post-Classical Period (1200-1900 CE)”, with<br />

Prof. Mohammed Ali Amir-Moezzi,35 Ecole Pratique <strong>de</strong>s Hautes Etu<strong>de</strong>s,<br />

Paris, with Prof. Ayman Sheha<strong>de</strong>h, School of Oriental and African Studies,<br />

London, with Prof. Peter Adamson, King’s College, London, and<br />

Munich University, with Professor Ulrich Rudolph (Zürich) on the Ueberweg:<br />

Grundriss <strong>de</strong>r Geschichte <strong>de</strong>r Philosophie (Islamische Philosophie),<br />

with Prof. Maribel Fierro, <strong>Consejo</strong> <strong>Superior</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Investigaciones</strong> Científicas,<br />

Madrid,36 with Prof. Khaled el-Rouayheb, Islamic Intellectual History,<br />

Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University,37 with<br />

Prof. David Hollenberg, University of Oregon,38 and Prof. Bernard Haykel<br />

and Dr. David Magier, Princeton University and Princeton University Library<br />

on “The Yemeni Manuscripts Digitization Initiative” (YMDI),39 and<br />

with Boris Zaykovsky, Russian National Library, St. Petersburg.<br />

Within Germany, the Research Unit is collaborating closely with the<br />

recently foun<strong>de</strong>d Center for Islamic Theology (Zentrum für Islamische<br />

Theologie), Tübingen, directed by Prof. Omar Hamdan, a former member<br />

of the Research Unit (2010–11).40 The Research Unit is also closely<br />

cooperating with the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin in a variety of research<br />

projects and conferences.41<br />

♦<br />

18 http://pluto.huji.ac.il/~stroums/.<br />

19 http://cnrs.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/RonnyVollandt<br />

20 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/ZeusWellnhofer.<br />

21 http://fu-berlin.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/EvaMariaZeis.<br />

22 http://www.isam.org.tr/; http://english.isam.org.tr/.<br />

23 http://uludag.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/KadirG\%C3\%B6mbeyaz.<br />

24 http://uludag.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/veyselkaya; http://ilahiyat.uludag.edu.tr/tr/aka<strong>de</strong>mikkadro/<br />

kadro/408-veysel-kaya.html.<br />

25 http://www.izbacf.org/.<br />

26 http://www.cgie.org.ir/.<br />

27 http://www.mirasmaktoob.ir/.<br />

28 http://www.kfcris.com/.<br />

29 http://www.almajidcenter.org/Arabic/Pages/<strong>de</strong>fault.aspx/.<br />

30 http://www.intellectualencounters.org/.<br />

31 http://telaviv.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/CamillaAdang; http://vimeo.com/38437580.<br />

32 http://www.tau.ac.il/humanities/vip/polliackm.htm.<br />

33 http://islamsci.mcgill.ca/RASI/pipdi.html.<br />

34 http://religiousstudies.dal.ca/Faculty%20and%20staff/Alexan<strong>de</strong>r_Treiger.php.<br />

35 http://www.ephe.sorbonne.fr/annuaire-<strong>de</strong>-la-recherche/mamirmoezzi.html.<br />

36 http://csic.aca<strong>de</strong>mia.edu/maribelfierro.<br />

37 http://tinyurl.com/nelc-fas-harvard-edu-rouayheb.<br />

38 http://ymdi.uoregon.edu/.<br />

39 http://ymdi.uoregon.edu/.<br />

40 http://www.uni-tuebingen.<strong>de</strong>/einrichtungen/verwaltung-<strong>de</strong>zernate/i-forschung-strategie-undrecht/zentrum-fuer-islamische-theologie.html.<br />

41 See, e.g., http://staatsbibliothek-berlin.<strong>de</strong>/nc/die-staatsbibliothek/ausstellungen-undveranstaltungen/<strong>de</strong>tail/article/<strong>2012</strong>-01-12-5714/.<br />

12 13

The work of the Research Unit Intellectual History of<br />

the Islamicate World and its research areas<br />

Executive Summary<br />

Intellectual richness and unparalleled variety characterize the Islamicate<br />

world throughout its history and a fundamental un<strong>de</strong>rstanding<br />

of the intellectual history of the Islamic cultural sphere is possible<br />

only if research is not confined within <strong>de</strong>nominational boundaries. The<br />

Qurʾān regards itself as the last, perfect link in a chain of progressive<br />

divine revelations. It is, thus, very much aware of its own generic<br />

linkage to the two preceding monotheistic religions, Judaism and Christianity.<br />

The early Muslims adopted many Jewish and Christian elements<br />

as they had evolved during Late Antiquity. Christians and Jews were<br />

also involved in shaping Muslim intellectual history in subsequent<br />

centuries. From the 9th century CE Muslims, Christians and Jews shared<br />

a common everyday and cultural language, Arabic, which they used<br />

to communicate i<strong>de</strong>as, concepts and texts, and the ensuing exchange was<br />

mutually enriching. For centuries representatives of all three religions<br />

read a very similar canon, especially in the so-called rational sciences<br />

(theology, philosophy, aspects of legal methodology, the natural sciences,<br />

and medicine) and belles lettres and thus contributed to its <strong>de</strong>velopment.<br />

The dynamic was multi-dimensional. Christian and Jewish authors influenced<br />

Islamic thought, while the writings of Muslim thinkers had an<br />

impact on non-Muslims. Interreligious interaction is a historical fact<br />

that continues into the mo<strong>de</strong>rn age.<br />

While this has been amply <strong>de</strong>monstrated for some selected periods and<br />

regions, scholars usually opt for a one-dimensional approach with an (often<br />

exclusive) focus on either Muslim, Jewish or Christian authors and<br />

their writings. In all three fields and for a variety of reasons, the scholarly<br />

investigation of the “rational sciences” beyond <strong>de</strong>nominational bor<strong>de</strong>rs is<br />

still in the beginning phase. This calls for an entirely new framework<br />

for innovative research that systematically crosses the boundaries<br />

between three major disciplines of aca<strong>de</strong>mia and research, viz. Islamic<br />

Studies, Jewish Studies and the study of Eastern Christianity.<br />

This approach characterizes the work carried out at the Research Unit<br />

Intellectual History of the Islamicate World.<br />

♦<br />

Detailed Description of the Research Areas and the Current<br />

Projects:<br />

Critical Avicennism in the Islamic East of the 12th century<br />

The reception of the philosophy of Avicenna (d. 1037) in the Islamic and<br />

Christian West has been documented for some time. Less un<strong>de</strong>rstood is<br />

the reception of Avicenna’s philosophy in the East of the Islamic<br />

world, where it occurred on a much greater scale and proved much more<br />

momentous. Two hundred years after the <strong>de</strong>ath of Avicenna, major con-<br />

14

cepts of his philosophy had become an integral part of new philosophical<br />

schools and traditional disciplines.<br />

Yet only rarely was Avicenna’s philosophical system accepted wholesale.<br />

Especially during the 12th century, various thinkers interpreted and reevaluated<br />

his works from a number of perspectives. While they generally<br />

retained Avicenna’s conceptual framework, they modified or relinquished<br />

some of his most central tenets. They did so for various reasons. Some<br />

attempted to resolve problems inherent to the Avicennan system. Others<br />

tried to integrate Avicennan i<strong>de</strong>as into hitherto nonphilosophical contexts.<br />

This process and the philosophical concepts and positions resulting<br />

from this process will be termed “critical Avicennism”.<br />

To better un<strong>de</strong>rstand the formation of critical Avicennism, members of the<br />

Research Unit study figures and writings from the 12th century that<br />

are central to this process. They aim to draw the intellectual landscape of<br />

that period, to make important texts accessible, and to un<strong>de</strong>rstand the<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopments of central philosophical concepts in <strong>de</strong>tail.<br />

The works of the famous 12th-century logician and philosopher ʿUmar<br />

b. Sahlān al-Sāwī in <strong>de</strong>fense of Avicennan philosophy (Lukas Muehlethaler<br />

/ Reza Pourjavady) illustrate the reaction to critical Avicennism<br />

and the modification of Avicennan tenets in its wake. Two philosophical<br />

works of ʿUmar b. Sahlān, his Nahj al-taqdīs and his response to criticisms<br />

of Avicennan philosophy, are being critically edited and ma<strong>de</strong> accessible<br />

through translation and analysis. In these works, ʿUmar b. Sahlān <strong>de</strong>fends<br />

central Avicennan concepts against critiques by al-Shahrastānī (d. 1153)<br />

and Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī (d. after 1164-5). The monograph, Defending<br />

Avicennan Philosophy: ʿUmar b. Sahlān al-Sāwī in Response to the Criticisms<br />

of Abū al-Barakāt al-Baghdādī and Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-Karīm al-<br />

Shahrastānī, will be ready for the press in 2013.<br />

A study of Abū l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī’s philosophical work and its<br />

reception (Lukas Muehlethaler) looks at how key concepts in Avicenna’s<br />

philosophy are transformed by Abū l-Barakāt and how the<br />

transformed concepts are taken up by Abū l-Barakāt’s contemporaries<br />

and later thinkers. Chief among them is Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 1210)<br />

whose conceptualization of philosophical positions is of central importance<br />

for 13th-century Arabic philosophy and theology. Fakhr al-Dīn’s<br />

reception and transformation of the Avicennan tradition in general and<br />

Abū l-Barakāt’s philosophy in particular are therefore traced through a<br />

number of case studies.<br />

♦<br />

Muslim and Jewish philosophy intertwined during the 13th through<br />

15th centuries<br />

Apart from the towering figure of Abū l-Barakāt, the Jewish philosopher<br />

and convert to Islam of the 12th century, there are many additional examples<br />

of Jewish and Muslim thinkers who were well-versed in both religious<br />

traditions and who left an impact on Jewish and Muslim rea<strong>de</strong>rs<br />

alike. One of the most prominent Jewish philosophers belonging to this<br />

category is ʿIzz al-Dīn Ibn Kammūna. Ibn Kammūna was born into<br />

a Jewish family of 13th century Baghdad and received a thorough<br />

education in both Jewish and Islamic letters. Little is known about<br />

his life but it is evi<strong>de</strong>nt that he held a high-ranking position in the administration<br />

of the Ilkhānid empire, although there is no indication that<br />

he ever converted to Islam. Like many Muslim scholars of his time, he<br />

enjoyed the patronage of the Minister of State, Shams al-Dīn al-Juwaynī<br />

(d. 1284) and his family, to whom he <strong>de</strong>dicated most of his works. He<br />

also correspon<strong>de</strong>d with the most important intellectuals of his time. Ibn<br />

Kammūna’s philosophical writings and particularly his commentary<br />

on the Kitāb al-Talwīḥāt by Shihāb al-Dīn al-Suhrawardī, as well as his<br />

in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nt works in this discipline significantly shaped the <strong>de</strong>velopment<br />

of Islamic philosophy in the Eastern lands of Islam over<br />

the following centuries. The Research Unit (Sabine Schmidtke / Reza<br />

Pourjavady) is currently preparing critical editions of Ibn Kammūna’s<br />

commentary on Avicenna’s Remarks and admonitions (al-Ishārāt wal-tanbīhāt)<br />

(editio princeps) and of his Examination of the three religions<br />

(Tanqīḥ al-abḥāth li-l-milal al-thalāth). A monograph on Ibn Kammūna’s<br />

theory of the soul (Lukas Muehlethaler) is about to go to press.<br />

The vast holdings of manuscript collections of Jewish provenance (esp.<br />

the Abraham Firkovitch collection in St. Petersburg) in many respects<br />

still await scholarly exploration and the material they contain specifically<br />

for the later period (12th through 15th centuries and beyond) is bound to<br />

change our current perception of Jewish philosophy in the lands of Islam<br />

and its intertwinedness with the Muslim environment significantly as research<br />

progresses. Sabine Schmidtke is engaged with the literary output<br />

of the intriguing figure of David ben Joshua Maimoni<strong>de</strong>s (d. 1415), the<br />

last head of the Jewish community of Egypt from the <strong>de</strong>scendants of Moses<br />

Maimoni<strong>de</strong>s. In contrast to Ibn Kammūna’s, his professional life took<br />

place within the confines of the Jewish community(ies) and his works (all<br />

written in Arabic, but in Hebrew characters) circulated exclusively among<br />

Jewish rea<strong>de</strong>rs. Born in Egypt, David succee<strong>de</strong>d his father Joshua Maimoni<strong>de</strong>s<br />

as nagīd or Head of the Community following the latter’s <strong>de</strong>ath<br />

in 1355. For reasons that remain unclear, he left his homeland to take up<br />

resi<strong>de</strong>nce in Syria for a <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong> during the 1370s and 1380s. He resumed<br />

his office as head of the community after his return to Egypt and retained<br />

it until his <strong>de</strong>ath. Apart from being a prolific author himself, David is<br />

well known as a book collector and an accomplished scribe, and numerous<br />

copies of works in his hand by earlier Jewish and Muslim authors in<br />

a variety of disciplines have survived. It was particularly during his time<br />

in Aleppo that David assembled an impressive library containing numerous<br />

copies of works that he had either commissioned or copied himself.<br />

These testify to his scholarly abilities and his erudition in both the Jewish<br />

and Muslim literary traditions. He wrote a commentary on Maimoni<strong>de</strong>s’<br />

Mishneh Torah, an influential co<strong>de</strong> of Jewish law, as well as<br />

numerous works in the fields of ethics, philosophy, logic as well as a comprehensive<br />

handbook of Sufi mysticism. These works testify to David’s<br />

<strong>de</strong>ep immersion into a variety of Muslim rational sciences. In philosophy,<br />

he was not only familiar with the peripatetic thought of Avicenna, but<br />

also acquainted with numerous writings of the foun<strong>de</strong>r of Illuminationist<br />

philosophy, Shihāb al-Dīn al-Suhrawardī, and he may have possessed<br />

a copy of Ibn Kammūna’s commentary on Suhrawardī’s K. al-Talwīḥāt.<br />

David was likewise familiar with the writings of the renowned Muslim<br />

thinker Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazzālī (d. 1111) and of the latter’s stu<strong>de</strong>nt Fakhr<br />

al-Dīn al-Rāzī. In addition, he quotes extensively from the earlier Muslim<br />

literature on mysticism, and was evi<strong>de</strong>ntly well-versed in the Muslim as-<br />

16 17

tronomical tradition.<br />

Although none of the works of David ben Joshua ever reached a wi<strong>de</strong>r<br />

Muslim rea<strong>de</strong>rship, as was the case with the writings of his co-religionist<br />

Ibn Kammūna, he did reach out on a more personal level. During his<br />

time in Syria, David befrien<strong>de</strong>d the Muslim scholar ʿAlī b. Ṭaybughā<br />

al-Ḥalabī al-Ḥanafī al-Muwaqqit (d. 1391?), who wrote a commentary<br />

on Maimoni<strong>de</strong>s’ Mishneh Torah (Book of Knowledge, Fundamental<br />

precepts of the Torah I–IV) based on an Arabic translation by David ben<br />

Joshua and the latter’s own commentary. Both commentaries are extant<br />

in manuscript and provi<strong>de</strong> evi<strong>de</strong>nce for a fruitful and stimulating exchange<br />

between two distinguished scholars of the 15th century, a Jew and<br />

a Muslim, on the fundamental issues of a Jewish Co<strong>de</strong> of Law. These commentaries<br />

are being closely studied and will be edited by Gregor Schwarb.<br />

Philosophy in Iran during the Ṣafavid and Qajar Periods<br />

♦<br />

During the Ṣafavid period (1502–1736), Iranian philosophy was characterized<br />

by two main strands, one following the thought of Ṣadr al-Dīn al-<br />

Shīrāzī (“Mullā Ṣadrā”, d. 1640), the other strand following that of Rajab<br />

ʿAlī al-Tabrīzī (d. 1669). While much scholarly attention has been paid<br />

over the last <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s to the renowned Mullā Ṣadrā, Rajab ʿAlī al-Tabrīzī<br />

and his exten<strong>de</strong>d circle of stu<strong>de</strong>nts has so far mostly escaped scholars’<br />

attention. One of the projects of the Research Unit (Ahmad Reza Rahimi<br />

Riseh) is therefore concerned with his philosophical œuvre and its reception.<br />

Five of his works have been preserved in manuscript. In addition to<br />

this, the writings of his numerous stu<strong>de</strong>nts are another major source for<br />

the reconstruction of his thought. The most important of his stu<strong>de</strong>nts are<br />

Muḥammad Rafīʿ Pīrzā<strong>de</strong>h (d. first half 18th c.), ʿAlī Qulī Qaračaġāy Khān<br />

(d. after 1680), Qawām al-Dīn Muḥammad al-Rāzī (d. 1683), Mullā Ḥasan<br />

al-Lunbānī (d. 1683), Mullā ʿAbbās al-Mulawī (d. after 1690), Muḥammad<br />

b. Mufīd (“Qāḍī Saʿīd al-Qummī”, d. 1695), Muḥammad Ismāʿīl b.<br />

Muḥammad Bāqir al-Khwātūnābādī (d. 1704) and Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-<br />

Fattāḥ al-Tunkābunī (“Fāḍil-i Sarāb”, d. 1712). The project aims at reconstructing<br />

Rajab ʿAlī al-Tabrīzī’s biography, providing a <strong>de</strong>tailed inventory<br />

of his writings with <strong>de</strong>scriptions of all preserved manuscripts, a study of<br />

his stu<strong>de</strong>nts and their writings, as well as an analysis of his philosophical<br />

thought in comparison with that of his contemporary Mullā Ṣadrā.<br />

Next to nothing is known in mo<strong>de</strong>rn scholarship about the rich philosophical<br />

tradition in Iran during the Qajar period. One of the current<br />

projects of the Research Unit (Reza Pourjavady / Sabine Schmidtke)<br />

is therefore to edit a collective volume <strong>de</strong>voted to this period, The Philosophical<br />

Tradition in Iran during the Qajar Period (1794–1925). Each chapter<br />

will treat one key thinker of the period and will be written by a leading<br />

Western or Iranian experts in the field: Chapter One: Shaykh Aḥmad<br />

al-Aḥsāʾī (by Hassan Ansari); Chapter Two: Mullā Muḥammad Mahdī<br />

Narāqī (by Reza Pourjavady); Chapter Three: Mullā ʿAlī Nūrī (by Sajjad<br />

Rizvi); Chapter Four: Mullā Hādī Sabzavārī (by Fatemah Fana); Chapter<br />

Five: Āqā ʿAlī Mudarris Zunūzī (by Mohsen Kadivar); Chapter Six: Mīrzā<br />

Abū l-Ḥasan Jilva (by Encieh Barkhah); Chapter Six: Lithograph Editions<br />

of Philosophical and Theological Works in Qajar Iran (by Reza Pourjavady<br />

/ Sabine Schmidtke). The publication of the volume is envisaged for 2013.<br />

One of the characteristic features of this period is the increased interest<br />

in ancient Greek philosophical texts and pre-Avicennan philosophical<br />

writings. The intellectual en<strong>de</strong>avour in an attempt to shed light<br />

on the legacy of Greek philosophy can be traced back to the end of the<br />

15th century to Shiraz which was at the time the main cultural centre<br />

of philosophy in the Eastern lands of Islam. Here, the two main figures<br />

who initiated the Eastern renaissance movement were Jalāl al-Dīn al-<br />

Dawānī (d. 1502) and Ghiyāth al-Dīn al-Dashtakī (d. 1541-42). Gradually,<br />

a large corpus of Graeco-Arabica (including pseudo-Graeco Arabica)<br />

was assembled by scholars, one of the most significant texts being the socalled<br />

Theologia Aristotelis, an adapted paraphrase of sections of Enneads<br />

IV to VI of Plotinus, which had ma<strong>de</strong> an immense impact in Christian,<br />

Muslim and Jewish circles during the 16th and 17th centuries. In a<br />

joint project, Reza Pourjavady and Sabine Schmidtke study this shift and<br />

its consequences in the Muslim philosophical writings of the 16th, 17th,<br />

and 18th centuries. With the help of an archive containing digitized copies<br />

of all the relevant manuscripts produced from the early 16th to late<br />

18th centuries and a database with an analytical <strong>de</strong>scription of the extant<br />

manuscripts they are examining the corpus of Greek and pre-Avicennan<br />

Muslim philosophical works that was copied/read during this<br />

period. Moreover, Muslim philosophical works written in this period are<br />

being examined in or<strong>de</strong>r to study the appropriation of the Graeco-<br />

Arabica by the Muslim philosophers of the period un<strong>de</strong>r investigation.<br />

Aesthetics<br />

♦<br />

In addition to the rigorous philosophical inquiries into post-Avicennan<br />

philosophy and intellectual history, there are projects that are more thematic<br />

such as the topic of aesthetics (Samir Mahmoud). Despite the<br />

existence of numerous studies of Islamic art and architecture, there is a<br />

<strong>de</strong>arth of scholarship in what precisely links these works to the overall<br />

intellectual and cultural climate of their time, particularly its aesthetic<br />

sensibilities. What complicates the matter is the conspicuous absence<br />

of an Arabic equivalent to the word ‘aesthetics’. The lack of terminology,<br />

however, does not mean that the themes and correlata suggested<br />

by the term ‘aesthetics’ were not discussed in medieval Islamic<br />

thought. Muslims not only enjoyed beauty but promoted the arts.<br />

The precise nature of this relationship between art and beauty <strong>de</strong>pends<br />

on the author, period, and school of thought un<strong>de</strong>r consi<strong>de</strong>ration.<br />

Regardless of the different approaches to beauty, one can safely say that<br />

medieval Muslim philosophers, theologians, and mystics always<br />

discussed aesthetics in the context of their discussions on metaphysics,<br />

theology, or ethics and not as a sui generis topic in any mo<strong>de</strong>rn<br />

sense. The task of exploring such a wi<strong>de</strong> range of source is an onerous<br />

one that requires the patient scholar to search in many different places.<br />

He has to turn to the philosophical works that address questions of<br />

intelligible beauty and the nature of sensible beauty inherited from the<br />

Greek texts; mystical works that discuss the beauty of the world as instances<br />

or manifestations of Divine Beauty; theological discussions on<br />

18 19

the signs of God in nature, discussions about the divine attributes such as<br />

we find in the kalām disputes of the Muʿtazilites and Ashʿarites; ethical,<br />

moral, and jurispru<strong>de</strong>ntial treatises that warn of the dangers of sensuous<br />

pleasure; literary discussions of aesthetics in poetry; discussions<br />

of vision and how the perception of an object affects the perceiver such<br />

as we find in the field of optics; various Sufi writings on the nature of<br />

perception and matter; alchemy and how one thing can be ma<strong>de</strong> to appear<br />

as another; psychology, particularly writings on dreams and the<br />

imagination; and ‘licit magic,’ i.e. treatises that often discuss the allure<br />

and magical power of poetry, geometrically <strong>de</strong>signed talismans, and images<br />

or what is referred to as apotropaic. In the above-mentioned sources<br />

there are either direct references to the correlata of aesthetics or else<br />

indirect and implicit assumptions about their nature vis-à-vis their relationship<br />

to the entire metaphysical, philosophical, theological, mystical,<br />

scientific, or ethical framework within which they are discussed. It<br />

is more accurate, then, to speak of the existence of a multiplicity of aesthetic<br />

sensibilities. The focus on Ibn ʿArabī (d. 638/1240) in this research<br />

project stems from the importance of Ibn ʿArabī and his legacy in<br />

post-Avicennan Islamic intellectual history. In regards to the relevance<br />

of Ibn ʿArabī to aesthetics, his theory of ‘the imagination’ and<br />

‘liminal images’ as intermediaries between different realms of meaning<br />

that both reveal and conceal in an ambiguous manner have a lot to offer<br />

a theory of art as mediation and the nature of re-presentation and<br />

mimesis. His theory on how the imagination works can significantly<br />

enrich contemporary un<strong>de</strong>rstandings of the relation between geometric<br />

signification and imaginative programs suggested by the geometric art<br />

and the nature of the creative process. His un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of sympathy<br />

and ornament as animated can contribute to the art historical and<br />

anthropological <strong>de</strong>bate surrounding the significance of ornament. He also<br />

offers a brilliant psychological analysis of ‘images’ and the imaging<br />

process, why certain traditions have figurative representation. Moreover,<br />

his is the first lucid and internally coherent account of the ban on figuration<br />

in the Islamic tradition. He presents a fresh and renewed appreciation<br />

for the meaning of ‘the abstract’ and ‘the geometric,’ their relation to<br />

‘representational images,’ and their fundamental role in art and religion.<br />

His theory of love as that which is occasioned by beauty can as much<br />

explain the erotic gaze and offer a theory of the beautiful as the daemon<br />

in Plato’s Symposium, and his theory of language and writing as a<br />

distinct mo<strong>de</strong> of being remains to be explored from an aesthetic point of<br />

view. The continuity of many of these themes throughout his commentators<br />

and the possible influence it may have had on the <strong>de</strong>velopment of<br />

the arts in the Ottoman and Safavid lands has yet to be explored. There is<br />

yet another significance to Ibn ʿArabī that is more contemporary. The rise<br />

to prominence of abstract art in the 20th century poses an interesting<br />

path of inquiry regards to Islamic art in general and Ibn Arabī’s<br />

thought in particular. If one follows Alois Riegl’s notion of a Kunstwollen,<br />

one can bridge the temporal divi<strong>de</strong> between medieval abstract and<br />

geometric Islamic art and 20th century ornament and art through<br />

a serious intellectual <strong>de</strong>bate. This has already started in the pioneering<br />

scholarship of Islamic art historians such as Oleg Grabar, Gulru Necipoglu,<br />

and Valerie Gonzalez. The project will thus bring Islamic studies,<br />

Western aesthetics and art history, and anthropology into dialogue.<br />

In addition, it will offer, in lieu of Hans Belting’s latest book, Florence and<br />

Baghdad: Renaissance Art and Arab Science, a renewed appreciation for a<br />

distinct Islamic aesthetic sensibility not governed or evaluated on Western<br />

art historical terms.<br />

The formative period of Mysticism<br />

♦<br />

Together with Sara Sviri (Jerusalem), the Research Unit (Sabine Schmidtke)<br />

recently launched a new project aiming to explore aspects and trends<br />

of Islamic mysticism in its formative period and revisiting processes,<br />

themes, images, practices, terminology and thought mo<strong>de</strong>ls pertaining<br />

to the literary products of the 9th–11th centuries, which <strong>de</strong>marcates the<br />

formative period of Islamic mysticism. Un<strong>de</strong>rlying this approach is the<br />

contention that within Islamic studies a typological and comparative approach<br />

to the origins of Islamic mysticism is a <strong>de</strong>si<strong>de</strong>ratum. The literary<br />

corpora pertaining to this period, Sufi and non-Sufi alike, contain materials<br />

which may shed new light on the versatility and fluidity of the<br />

prevailing mystical trends during this early period. Thus, although issues<br />

pertaining to Sufism will remain central to this research, other, non-Sufi,<br />

mystical mo<strong>de</strong>ls and trends are being explored whose portrayal, in both<br />

the original compilatory and hagiographic literature as well as in mo<strong>de</strong>rn<br />

scholarship, has hitherto been marginalized. The aim is to address<br />

such oversights and to offer a more complete picture of the topic un<strong>de</strong>r<br />

discussion by exploring a wi<strong>de</strong> range of textual sources – some published<br />

and many still in manuscript – by pursuing rigorous text-based philology<br />

together with historical, prosopographic and comparative-thematic<br />

methodologies. The project proceeds along three main axes, first the continuum<br />

of Late Antique trends, motifs, topoi and practices; secondly<br />

the build-up of Sufi culture from local centres to an all-inclusive<br />

movement; thirdly philosophical mysticism and theological trends.<br />

Within this field, the Research Unit (Hassan Ansari / Sabine Schmidtke)<br />

is collecting, sorting out and analyzing hitherto unconsulted material relating<br />

to the Sufi-Ashʿarite connection in Nishapur – notably some of the<br />

works of Abū Saʿd al-Khargūshī (d. 1015-16) that were believed to be<br />

lost – Khargūshī being marginalized in current Sufi studies but whose<br />

importance as a witness to early processes and <strong>de</strong>finitions has been duly<br />

highlighted by Sara Sviri. Moreover, together with Sara Sviri the Research<br />

Unit also explores the engagements with Sufism of other theological<br />

schools active in Nishapur and Khurasan such as the Karrāmiyya and<br />

the Ḥanafiyya. Studies in the background of Christian (Syriac) monasticism<br />

and “ascetism” will eventually also be consi<strong>de</strong>red.<br />

Rationalism and Rational Theology in the Islamicate World<br />

♦<br />

Rationalism has been a salient feature of Muslim theological thought<br />

from the earliest times. Despite the fact that rationalism had its opponents<br />

throughout Islamic history, it continued to be one of the mainstays<br />

of Muslim theological (and legal) thought, and it is only in the wake of<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>rn Islamic fundamentalism that rationalism has become marginal-<br />

20 21

ized and threatened as never before.<br />

The disputed issue of authenticity notwithstanding, a small corpus of<br />

texts is extant in which doctrinal issues such as free will versus <strong>de</strong>terminism<br />

are <strong>de</strong>alt with in a dilemmatic dialogue pattern. The display of<br />

the dialectical technique in these texts testifies to the use of reason in<br />

the formulation of and argumentation for doctrinal issues from a very<br />

early period onwards. There is a near-consensus among contemporary<br />

scholars that the Muslim dialectical technique of kalām can be traced<br />

back to similar patterns of dilemmatic dialogue that were characteristic<br />

for the Christological controversies raging in 6th century Alexandria<br />

and, more importantly, 7th century Syria. These are based on late antique<br />

(“pagan”) schools of rhetorics.<br />

The Muʿtazila was the earliest “school” of rationalist Islamic theology<br />

and one of the most important and influential currents of Islamic<br />

thought. Muʿtazilites stressed the primacy of reason and free will and <strong>de</strong>veloped<br />

an epistemology, ontology and psychology that provi<strong>de</strong>d a basis<br />

for explaining the nature of the world, God, man and the phenomena of<br />

religion. In their ethics, Muʿtazilites maintained that good and evil can be<br />

known solely through human reason. The Muʿtazila had its beginnings in<br />

the 8th century and its classical period of <strong>de</strong>velopment was from the latter<br />

part of the 9th until the middle of the 11th century. The movement gradually<br />

fell out of favour in Sunni Islam and had largely disappeared by the<br />

14th century. Its impact, however, continued to be felt in Shīʿī Islam where<br />

its influence subsisted through the centuries. Moreover, mo<strong>de</strong>rn research<br />

on the Muʿtazila from the beginning of the 20th century onwards gave<br />

rise to a renaissance of the Muʿtazilite notion of rationalism finding its<br />

expression in the so-called “Neo-Muʿtazila”.<br />

Within the field of Islamic Studies, scientific research of Muslim rational<br />

theology is a comparatively young discipline, as a critical mass<br />

of primary sources became accessible only at a relatively late stage.<br />

Muʿtazilite works were not wi<strong>de</strong>ly copied and few manuscripts have survived.<br />

So little authentic Muʿtazilite literature was available that until the<br />

discovery of a significant number of Muʿtazilite texts in the early 1950’s<br />

in Yemen, Muʿtazilite doctrine was mostly known through the works of<br />

its opponents.<br />

Second in importance in the use of rationalism was the theological movement<br />

of the so-called Ashʿariyya, named thus after its eponymous<br />

foun<strong>de</strong>r, Abū l-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī (d. 935). Ashʿarī and his followers aimed<br />

at formulating a via media between the two dominant opposing strands<br />

of the time, Muʿtazilism and traditionalist Islam. Methodologically, they<br />

applied rationalism in their theological thought as was characteristic for<br />

the Muʿtazila while still maintaining the primacy of revelation over that<br />

of reason. Doctrinally, they upheld the notion of ethical subjectivism<br />

as against the ethical objectivism of the Muʿtazila. On this basis, they<br />

<strong>de</strong>veloped their own theological doctrines. Within the Sunni realm at<br />

least, Ashʿarism proved more successful and enjoyed a longer life than<br />

Muʿtazilism, yet, like Muʿtazilism, Ashʿarism was constantly challenged<br />

by traditionalist opponents rejecting any kind of rationalism.<br />

While mo<strong>de</strong>rn research on the Muʿtazila has begun relatively late, research<br />

on Ashʿarism started already in the 19th century, due to the fact<br />

that more manuscripts of Ashʿarite texts are preserved in European libraries<br />

than Muʿtazilite ones. Major landmarks in the 20th century were<br />

22 23

the publications of R. J. McCarthy in 1953 and 1957. Additional advances<br />

in recent <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s were ma<strong>de</strong> by the numerous studies of M. Allard, R.<br />

M. Frank and D. Gimaret. In addition to the efforts by Western scholars,<br />

many scholars in the Islamic world have also contributed significantly<br />

to the research of this movement. This progress notwithstanding, many<br />

<strong>de</strong>si<strong>de</strong>rata remain in the scholarly investigation of the Ashʿariyya,<br />

particularly with respect to the earlier phase of the movement. Among the<br />

most spectacular findings by a member of the Research Unit were two so<br />

far completely unknown manuscripts of the opus magnum by the important<br />

Ashʿarite theologian Abū Bakr al-Bāqillānī, Hidāyat al-mustarshidīn<br />

in Russia and Uzbekistan.<br />

The various strands of rational Muslim theological thought within<br />

Islam are closely related to each other as they were shaped and reshaped<br />

in a continuous process of close interaction between its respective<br />

representatives. This also holds true for other theological schools<br />

that were less prominent in the central areas of the Islamic world, such as<br />

the Māturīdiyya (named thus after its eponym Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī,<br />

d. 944) which was heavily in<strong>de</strong>bted to traditional Ḥanafite positions and<br />

to Muʿtazilite thought alike, but whose centre was in the North-East of<br />

Iran so that it has ma<strong>de</strong> relatively little impact. Of consi<strong>de</strong>rable importance<br />

is also the Ibāḍiyya, which reacted in many ways to Muʿtazilism<br />

(Wilferd Ma<strong>de</strong>lung / Abdurrahman al-Salimi).<br />

What has been stated about the close interaction between the various<br />

strands of thought within Islam equally applies to the relations of Islam<br />

with other religions that were most prominently represented in the medieval<br />

world of Islam, viz. Judaism and Christianity. Here, similar phenomena<br />

of reciprocity can be observed. Jews, Christians, and Muslims<br />

had Arabic as their common language and therefore naturally shared<br />

a similar cultural background. Often reading the same books and all<br />

speaking and writing in the same language, they created a unique intellectual<br />

commonality in which an ongoing, constant exchange of i<strong>de</strong>as,<br />

texts, and forms of discourse was the norm.<br />

Judaism proved much more receptive to basic Muslim doctrinal notions<br />

such as divine unicity than Christianity, and it was Muʿtazilism in particular<br />

that was adopted to varying <strong>de</strong>grees from the 9th century onwards<br />

by both Rabbanite and Karaite authors, so that by the turn of the 11th century<br />

a “Jewish Muʿtazila” had emerged. Jewish scholars both composed<br />

original works along Muʿtazilite lines and produced copies of Muslim<br />

Muʿtazilite books, often transcribed into Hebrew characters. The influence<br />

of the Muʿtazila found its way to the very centres of Jewish religious<br />

and intellectual life in the East. The Karaites and several of the Heads of<br />

the ancient Rabbanite Aca<strong>de</strong>mies (Yeshivot) of Sura and Pumbedita (located<br />

by the 10th century in Baghdad) adopted the Muʿtazilite worldview.<br />

By contrast, Ashʿarite works and authors were received among Jewish<br />

scholars to a significantly lesser <strong>de</strong>gree and in a predominantly critical<br />

way. The study of Jewish Muʿtazilism began a century ago with the<br />

works of S. Munk (1859) and M. Schreiner (1895). Schreiner and Munk,<br />

however, were not aware of the primary sources to be found among the<br />

various Genizah materials that had been discovered and retrieved during<br />

the second half of the 19th century in Cairo by a number of scholars<br />

and manuscript collectors. Among the many Muʿtazilite manuscripts<br />

found in the Abraham Firkovitch collection (taken from the former library<br />

of the Karaite Synagogue in Cairo) thirteen were <strong>de</strong>scribed in <strong>de</strong>tail<br />

by A.J. Borisov in an article published in 1935. Additional landmarks in the<br />

study of Jewish Muʿtazilism were H. A. Wolfson’s Repercussions of the Kalam<br />

in Jewish Philosophy (1979) and G. Vajda’s studies on Yūsuf al-Baṣīr,<br />

particularly his edition of Baṣīr’s al-Kitāb al-Muḥtawī on the basis of a<br />

manuscript from the Kaufmann collection in Budapest (1985). On the basis<br />

of Borisov’s <strong>de</strong>scriptions of the Firkovitch Muʿtazilite manuscripts and<br />

from fragments in the British Library, H. Ben-Shammai was able to draw<br />

additional conclusions regarding the i<strong>de</strong>ntity of some of the Muʿtazilite<br />

materials preserved by the Karaites.<br />

In 2003, the “Muʿtazilite Manuscripts Project Group” was foun<strong>de</strong>d<br />

by the head of the Research Unit Intellectual History of the Islamicate<br />

World, Sabine Schmidtke, and by the Director of Research, Center<br />

for the Study of Ju<strong>de</strong>o-Arabic Culture, Ben Zvi Institute (Jerusalem),<br />

David Sklare, in or<strong>de</strong>r to assemble and i<strong>de</strong>ntify as many fragments of<br />

Muʿtazilite manuscripts as possible from Jewish as well as Shīʿī repositories.<br />

Although much has been achieved over the past years, major textual<br />

resources still remain unexplored. Among the fragments of philosophical<br />

and theological texts found in the various Genizah collections, the material<br />

that originated in the Ben Ezra Genizah (Cairo) and is nowadays<br />

mostly preserved in the Taylor-Schechter collection at Cambridge University<br />

Library (and other libraries in Europe and the USA) is until now<br />

still largely uni<strong>de</strong>ntified and only rudimentarily catalogued. A systematic<br />

study of all Muʿtazilite fragments will ren<strong>de</strong>r the reconstruction of many<br />

more so far lost Muʿtazilite (Muslim and Jewish) writings possible. As<br />

such, this Genizah material significantly supplements the extensive findings<br />

of the manuscript material found in the Russian National Library in<br />

St. Petersburg, which likewise has so far only partly been explored.<br />

The Research Unit (Gregor Schwarb) has been working on the reconstruction<br />

of several key-texts of Jewish Muʿtazilism, such as Yeshuʿah ben<br />

Yehudah’s K. al-Tawriya or Sahl b. al-Faḍl al-Tustarī’s K. al-Īmāʾ and will<br />

edit a number of Muʿtazilite texts by Muslim authors which have only<br />

been preserved in Jewish manuscript collections (Omar Hamdan / Sabine<br />

Schmidtke / Gregor Schwarb).<br />

Muʿtazilism had also left its mark on the theological thought of the Samaritans.<br />

It is not clear whether Samaritans (whose intellectual centres<br />

between the 9th to the 11th centuries were mainly Nablus and Damascus)<br />

had studied Muslim Muʿtazilite writings directly or whether they rather<br />

became acquainted with them through Jewish adaptations of Muʿtazilism.<br />

The study of Samaritan literary activities in Arabic in general and of Samaritan<br />

Muʿtazilism in particular is still very much at the beginning. The<br />

only relevant text that has been partly edited and studied is the Kitāb al-<br />

Tubākh by the 11th century author Abū l-Ḥasan al-Ṣūrī, who clearly shares<br />

the Muʿtazilite doctrinal outlook. The majority of Samaritan theological<br />

writings composed in Arabic still await a close analysis. New insights into<br />

the quality of Samaritan Muʿtazilism will be presented in a forthcoming<br />

study on two newly i<strong>de</strong>ntified Samaritan treatises by Abū l-Ḥasan<br />

al-Ṣūrī and Munajjā b. Ṣedaqah (Gregor Schwarb).<br />

Moreover, Muslim theologians <strong>de</strong>voted much thought and energy to a<br />

critical examination and refutation of the views of Christianity and (to a<br />

lesser extent) Judaism, as is evi<strong>de</strong>nt from the numerous polemical tracts<br />

written by them against these religions. While the majority of refutations<br />

against Christianity by early Muslim theologians are lost,<br />

there are a few extant anti-Christian texts from the 9th century that give a<br />

24 25

good impression of the arguments that were employed. Moreover, many<br />

of the earliest treatises in <strong>de</strong>fense of Christianity in Arabic are preserved,<br />

and it is evi<strong>de</strong>nt that their authors were well acquainted with Muslim<br />

kalām techniques and terminology. Given the basic disagreements between<br />

Muslim and Christian theological positions, such as the Muslim<br />

notion of divine unicity (tawḥīd), which is incompatible with the Christian<br />

un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of trinity and incarnation, any kind of far-reaching<br />

adoption of any of the Muslim school doctrines by Christian theologians<br />

was out of question. The most intensive reception of Muslim kalām can be<br />

observed among Coptic and Syriac-orthodox writers (Bar Hebraeus<br />

and contemporaries) of the 13th and 14th centuries.<br />

Approximately all extant writings of the first generation of Christian<br />

mutakallimūn writing in Arabic have been edited and (partly) translated,<br />

and mo<strong>de</strong>rn scholars, such as S. H. Griffith and D. Thomas, have studied<br />

them in <strong>de</strong>tail. Likewise, all of the few extant anti-Christian writings by<br />

Muslim rational theologians have been published in critical editions. By<br />

contrast, much work still needs to be done on the vast corpus of Coptic<br />

Christian writings (13th and 14th c. CE), only few of which have so<br />

far been published in critical editions, let alone studied. It is this corpus<br />

that still needs to be ma<strong>de</strong> available in critical editions and to be studied<br />

in or<strong>de</strong>r to locate them within the “whirlpool” of intellectual activities<br />

in the medieval world of Islam. Through a comprehensive study on the<br />

reception of Maimoni<strong>de</strong>s and Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī in the writings<br />

of Coptic theologians of the 13th and 14th centuries and the edition<br />

of the two major works by al-Rashīd Abū l-Khayr Ibn al-Ṭayyib,<br />

Gregor Schwarb will highlight the contribution of Jewish and Muslim intellectual<br />

thought to the “Gol<strong>de</strong>n Age” of Copto-Arabic literature.<br />

Within the field of theological rationalism in the medieval world of Islam<br />

between the 10th and the 13th centuries beyond and across <strong>de</strong>nominational<br />

bor<strong>de</strong>rs, all major <strong>de</strong>si<strong>de</strong>rata have been i<strong>de</strong>ntified and are being<br />

addressed in a number of projects in the framework of the ERC Project<br />

“Rediscovering Theological Rationalism in the Medieval World<br />

of Islam”. Among the most important ongoing projects within this field<br />

are the Oxford Handbook of Islamic Theology (editor: Sabine Schmidtke)<br />

that will comprise some forty contributions by internationally renowned<br />

scholars in the field, among them all team members of the Research Unit.<br />

The publication of the Handbook is envisaged for 2013.<br />

Another more specific though at the same time groundbreaking project<br />

of the Research Unit is the Handbook of Muʿtazilite Works and Authors<br />

that has been accepted for publication by Brill (Lei<strong>de</strong>n) (editor: Gregor<br />

Schwarb). The work, which is close to completion, will discuss in <strong>de</strong>tail<br />

some 500 representatives of Muʿtazilism (Sunnis, Twelver Shīʿīs, Zaydīs<br />

and Jews), together with <strong>de</strong>tailed inventories of their respective theological<br />

writings and extant manuscripts.<br />

♦<br />

– was felt also in North-Africa and Islamic Spain (al-Andalus). Among<br />

the staunchest opponents of these two currents of rational theology was<br />

Abū Muḥammad Ibn Ḥazm (d. 1064) who was a representative of the<br />

Ẓāhirī or literalist approach to the sacred scriptures and who categorically<br />

rejected all theological speculation. This resulted in a series<br />

of works in which he vehemently polemicized against the teachings of<br />

both Muʿtazilites and Ashʿarites. The Research Unit (Sabine Schmidtke,<br />

in collaboration with Maribel Fierro and Camilla Adang) is finalizing a<br />

reference work <strong>de</strong>voted to the Ẓāhirī thinker Ibn Ḥazm, entitled Ibn<br />

Ḥazm of Cordoba: Life and Works of a Controversial Thinker, that will be<br />

published (early 2013) in the Brill series “Handbuch <strong>de</strong>r Orientalistik”. The<br />

majority of contributions were presented during an international conference<br />

held in Istanbul in 2008 (fun<strong>de</strong>d by the Gerda Henkel Foundation).<br />

The sections that will be covered in the volume are “Life and Times of Ibn<br />

Ḥazm”, “Legal Aspects”, “Ẓāhirī Linguistics”, “Art and Aesthetics”, “Theology,<br />

Philosophy and Ethics”, “Intra- and Interreligious Polemics”, “Reception<br />

and Impact on Medieval and Mo<strong>de</strong>rn Muslim thought”.<br />

Another project (Sophia Vasalou) focuses on the theology of the Hanbalite<br />

scholar Taqī al-Dīn Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328). Ibn Taymiyya represents<br />

an important case both in terms of the history of the changing<br />

relationship of Ḥanbalite theologians – traditionally distrustful of the<br />

methods of reason – to other theological schools, but also in terms<br />

of evolving accounts of the relationship between reason and revelation.<br />

In this context, Ibn Taymiyya’s view of ethics and the sources of<br />

moral knowledge holds particular significance. Ibn Taymiyya seeks to<br />

articulate a new via media between existing approaches to the nature of<br />

value which would transcend both Muʿtazilite and Ashʿarite configurations.<br />

Influenced both by his extensive readings of kalām as well as his<br />

wi<strong>de</strong>-ranging interests in falsafa, Ibn Taymiyya articulates a view that<br />

presents itself as a revised Muʿtazilism, claiming that reason <strong>de</strong>livers<br />

knowledge of the values of human actions. This claim involves a reworked<br />

un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of reason that brings it into close relationship with a new<br />

epistemological idiom, that of human nature or fiṭra. In this new configuration,<br />

the notion of welfare or maṣlaḥa comes to occupy a crucial<br />

role, and a heavy accent is placed on the role of <strong>de</strong>sire, as against reason,<br />

in the knowledge of good and evil. The <strong>de</strong>eper motivations of Ibn Taymiyya’s<br />

proposed synthesis are rooted in an un<strong>de</strong>rstanding of theology in<br />

which theological doctrines are un<strong>de</strong>rstood and assessed in terms of their<br />

pragmatic, or better said, “spiritual”, ends. Just how this synthesis relates<br />

to the existing theological possibilities represented by the Mu‘tazilite and<br />

Ash‘arite schools is a central question to consi<strong>de</strong>r in this connection, and<br />

one that holds the key to un<strong>de</strong>rstanding both the genuine innovativeness,<br />

as well as the true substance, of Ibn Taymiyya’s rationalism. Gaining a<br />

clearer view of Ibn Taymiyya’s ethical approach is of crucial importance,<br />

on the one hand, for refining our history of a theological <strong>de</strong>bate<br />

that played a significant part in Islamic theological self-un<strong>de</strong>rstanding. At<br />

the same time, and given the wi<strong>de</strong> diffusion of Ibn Taymiyya’s legacy<br />

in the mo<strong>de</strong>rn era, it may also enable us to construct the prolegomena<br />

for a history of contemporary theological <strong>de</strong>velopments.<br />

Counterreactions<br />

Although the Muʿtazila and the Ashʿariyya originated in the Eastern<br />

part of the Islamic world, their influence – especially that of the latter<br />

♦<br />

26 27

The intellectual and religious heritage of Shīʿism (Zaydism and<br />

Imamism)<br />

The scholarly investigation of Shīʿite Islam and its three branches, Twelver<br />

(or Imami) Shīʿism, Zaydism and Ismāʿīlism, began much later than that<br />

of Sunnī Islam, and Shīʿism has long been consi<strong>de</strong>red to be of marginal<br />

importance at best. The Iranian Revolution of 1979, which cannot be<br />

un<strong>de</strong>rstood without taking the legal characteristics of Twelver Shīʿism<br />

and its historical <strong>de</strong>velopment into consi<strong>de</strong>ration, has proved this evaluation<br />

to be wrong and since then the study of Twelver Shīʿite Islam is<br />

steadily on the rise. The study of Ismāʿīlism has been actively promoted<br />

over the last three <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s by the current imam of the Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs, Aga<br />

Khan IV (b. 1936), and the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London that was<br />

established in 1977 un<strong>de</strong>r his auspices. In contrast to these two branches<br />

of Shīʿite Islam, Zaydism has so far attracted much less scholarly attention,<br />

partly because it has been perceived as being more marginal than<br />

either Twelver Shīʿism (which is the state religion of Iran and a politically<br />

significant community in Lebanon, Iraq and the Arabian peninsula) and<br />

Ismāʿīlism (due to the active role of the Aga Khan in its scholarly investigation).<br />

However, the recent conflict in Yemen shows how important it<br />

is to un<strong>de</strong>rstand the legal and political notions of Zaydism, as its adherents<br />

represent some of the most significant political factions in the country,<br />

and their views will no doubt be an important factor in the future<br />

<strong>de</strong>velopments in Yemen.<br />

It is only during the last years that the vast holdings of the various private<br />

and smaller public libraries of Yemen are being ma<strong>de</strong> available<br />

to the scholarly community. While some of these materials have been<br />

used for various publications by members of the “Muʿtazilite Manuscripts<br />

Project Group”, the majority still awaits close study. This also applies to<br />

the <strong>de</strong>velopment of Muʿtazilite thought among the Zaydites from the 12th<br />

century onwards.<br />

The Research Unit (Hassan Ansari / Sabine Schmidtke / Gregor Schwarb /<br />

Jan Thiele) focusses on some of the most neglected fields of Zaydī thought<br />

and practice. Some results of these efforts are inclu<strong>de</strong>d in a special issue<br />

of the peer-reviewed journal Arabica: Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies/Revue<br />

d’étu<strong>de</strong>s arabes et islamiques, The neglected Šīʿites: Studies in<br />

the legal and intellectual history of the Zaydīs = Arabica 59 iii-iv (<strong>2012</strong>)<br />

that is published by Brill, Lei<strong>de</strong>n.<br />

Gregor Schwarb is preparing a comprehensive study of the <strong>de</strong>velopment<br />

of Zaydī legal methodology (uṣūl al-fiqh) that is closely related<br />

to Muʿtazilism on the one hand and to Ḥanafism on the other. Jan<br />

Thiele is focusing on Zaydī Yemenī doctrinal thought during the 12th<br />

and early 13th centuries that was primarily un<strong>de</strong>r the influence of the<br />

Muʿtazilite thought of the school of the Bahshamiyya. Besi<strong>de</strong> his in<strong>de</strong>pth<br />

studies into the ontology and cosmology of al-Ḥasan al-Raṣṣāṣ he is<br />

now preparing an editio princeps of the majority of the latter’s works on<br />

theology. One of the major concerns of al-Raṣṣāṣ was with the rival group<br />

of the Muṭarrifiyya, whose adherents upheld notions of natural causality<br />

and a cosmology that was inconceivable for mainstream Zaydism of<br />

the time. Hassan Ansari is currently preparing a comprehensive study<br />

on the doctrinal history of the Muṭarrifiyya. Hassan Ansari and Sabine<br />

Schmidtke further study the doctrinal <strong>de</strong>velopments of Yemeni Zaydī<br />