Education Libraries - Special Libraries Association

Education Libraries - Special Libraries Association

Education Libraries - Special Libraries Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

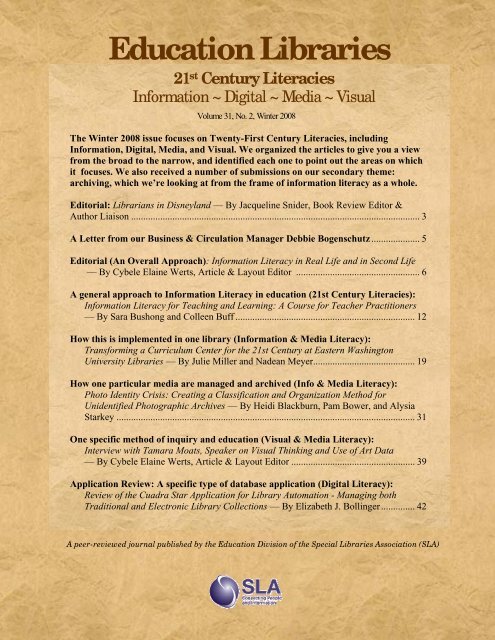

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong><br />

21 st Century Literacies<br />

Information ~ Digital ~ Media ~ Visual<br />

Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008<br />

The Winter 2008 issue focuses on Twenty-First Century Literacies, including<br />

Information, Digital, Media, and Visual. We organized the articles to give you a view<br />

from the broad to the narrow, and identified each one to point out the areas on which<br />

it focuses. We also received a number of submissions on our secondary theme:<br />

archiving, which we’re looking at from the frame of information literacy as a whole.<br />

Editorial: Librarians in Disneyland — By Jacqueline Snider, Book Review Editor &<br />

Author Liaison ....................................................................................................................... 3<br />

A Letter from our Business & Circulation Manager Debbie Bogenschutz .................... 5<br />

Editorial (An Overall Approach): Information Literacy in Real Life and in Second Life<br />

— By Cybele Elaine Werts, Article & Layout Editor ................................................... 6<br />

A general approach to Information Literacy in education (21st Century Literacies):<br />

Information Literacy for Teaching and Learning: A Course for Teacher Practitioners<br />

— By Sara Bushong and Colleen Buff .......................................................................... 12<br />

How this is implemented in one library (Information & Media Literacy):<br />

Transforming a Curriculum Center for the 21st Century at Eastern Washington<br />

University <strong>Libraries</strong> — By Julie Miller and Nadean Meyer.......................................... 19<br />

How one particular media are managed and archived (Info & Media Literacy):<br />

Photo Identity Crisis: Creating a Classification and Organization Method for<br />

Unidentified Photographic Archives — By Heidi Blackburn, Pam Bower, and Alysia<br />

Starkey ........................................................................................................................... 31<br />

One specific method of inquiry and education (Visual & Media Literacy):<br />

Interview with Tamara Moats, Speaker on Visual Thinking and Use of Art Data<br />

— By Cybele Elaine Werts, Article & Layout Editor ................................................... 39<br />

Application Review: A specific type of database application (Digital Literacy):<br />

Review of the Cuadra Star Application for Library Automation - Managing both<br />

Traditional and Electronic Library Collections — By Elizabeth J. Bollinger.............. 42<br />

A peer-reviewed journal published by the <strong>Education</strong> Division of the <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> <strong>Association</strong> (SLA)<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 1

Book Reviews<br />

Teaching Children 3 to 11: A Student’s Guide — Reviewed by Sheila Kirven........................46<br />

Information Literacy Instruction Handbook — Reviewed by Barbie E. Keiser...................... 47<br />

Teen Girls and Technology: What’s the Problem? What’s the Solution? — Reviewed by<br />

Michelle Price.......................................................................................................................... 48<br />

The Computer as an <strong>Education</strong>al Tool: Productivity and Problem Solving — Reviewed by<br />

Michelle Price.......................................................................................................................... 49<br />

Teaching Information Literacy: A Conceptual Approach — Reviewed by Barbie E. Keiser 50<br />

Curriculum Leadership: Development and Implementation<br />

— Reviewed by Gail K. Dickinson........................................................................................ 51<br />

More than 100 Tools for Developing Literacy—Reviewed by Barbie E. Keiser.................... 52<br />

No Challenge Left Behind: Transforming American <strong>Education</strong> Through Heart and Soul —<br />

Reviewed by Rachel Wadham................................................................................................. 53<br />

Deeper Learning: 7 Powerful Strategies for In-Depth and Longer Lasting Learning —<br />

Reviewed by Julie Shen........................................................................................................... 54<br />

Copyright Policies, Clip Note #39 — Reviewed by Jacqueline Snider................................... 55<br />

Why Do English Language Learners Struggle with Reading?: Distinguishing Language<br />

Acquisition from Learning Disabilities — Reviewed by Rachel L. Wadham......................... 56<br />

A History of the World Cup: 1930-2006 — Reviewed by Warren Jacobs.............................. 57<br />

A to Z of the Olympic Movement — Reviewed by Warren Jacobs.......................................... 58<br />

Gamers…in the Library?! The Why, What, and How of Videogame Tournaments for All Ages<br />

— reviewed by Elizabeth J. Bollinger..................................................................................... 59<br />

Assess for Success, 2 nd ed. — Reviewed by Celeste Moore.................................................... 60<br />

Keys to Curriculum Mapping: A Multimedia Kit for Professional Development —<br />

Reviewed by Gail K. Dickinson.............................................................................................. 61<br />

Librarians as Learning <strong>Special</strong>ists: Meeting the Learning Imperative for the 21 st Century —<br />

Reviewed by Erin Fields ......................................................................................................... 62<br />

New and Forthcoming - By Lori Maestre.................................................................................... 64<br />

Resources on the Net - Compiled By Chris Bober....................................................................... 69<br />

The <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> Review Board .................................................................................... 73<br />

Submissions .................................................................................................................................. 77<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 2

Librarians in Disneyland<br />

By Jacqueline Snider<br />

Book Review Editor &<br />

Author Liaison<br />

Water infiltrated the<br />

Midwest this summer. An<br />

unusually snowy and icy<br />

winter and a rainy spring<br />

produced flooding in<br />

Cedar Falls and Waterloo, then Cedar Rapids, and<br />

finally reached Iowa City in June. The University of<br />

Iowa was hit hard as Hancher Auditorium, the Art<br />

Museum, Music Building, Main Library, and many<br />

other buildings were in the “line of water.”<br />

Thousands left their homes. Cedar Rapids Public<br />

Library is a total ruin as are many municipal<br />

buildings and historic houses downtown.<br />

I am not relating these sad facts to elicit sympathy,<br />

although the communities affected could certainly<br />

use it, but because I found references to the floods<br />

everywhere I did and did not go this summer.<br />

Initially, I planned to attend SLA in another<br />

waterlogged city, Seattle, but could not travel the<br />

twenty miles to the airport since the interstates were<br />

closed. Once the<br />

roads opened, I<br />

managed to book a<br />

flight to dry Los<br />

Angeles, and<br />

attended ALA in<br />

Anaheim.<br />

ALA sure knows<br />

how to put on a<br />

show. The<br />

conference was full<br />

of celebrities, Jamie<br />

Lee Curtis, Ron<br />

Reagan, Dr. Terry<br />

Brazelton; book<br />

signings featured<br />

Editorial<br />

the most recent Caldecott and Newbery winners.<br />

The vendors were out in force, marketing their<br />

wares, and talking to customers. And the sessions<br />

included food, food for thought, and references to<br />

food and the flood.<br />

The first flood comment I encountered occurred<br />

when I attended a session titled, Making the Switch<br />

from Print to Online: Why, When and How? One of<br />

the presenters showed a photograph of the<br />

devastated public library in Parkersburg, Iowa, and<br />

said that if the collection had been online, the<br />

library would not have lost as much. I didn’t realize<br />

that servers were waterproof. What about<br />

electricity; will it last forever?<br />

Another flood reference came during the session of<br />

contributed research papers. The presenter, Dr. Lisl<br />

Zach from Drexel, examined how librarians behave<br />

in a crisis. Her research focused on whether<br />

librarians use their information skills to assist the<br />

community after a disaster strikes. Her preliminary<br />

findings show that librarians, themselves, were too<br />

overwhelmed to offer basic services. Instead, their<br />

volunteer efforts centered on helping the<br />

community with food, clothing, and shelter, rather<br />

than utilizing their superior skills to locate<br />

information for the<br />

greater good.<br />

While the sessions I<br />

dipped into covered a<br />

wide range, I will<br />

touch on some<br />

highlights for brevity’s<br />

sake. “Reviews<br />

Outside the<br />

Mainstream” looked at<br />

alternative sources for<br />

book reviews.<br />

References were made<br />

to websites such as<br />

bookslut and<br />

booksense. There were<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 3

stories about authors who added positive reviews<br />

about their own books on amazon.com, and posted<br />

negative reviews about their competitors.<br />

The presenters covered comic books, graphic<br />

novels, and gaming interests in the library. I learned<br />

that some music is composed only for the game, and<br />

is not released anywhere else.<br />

In the session, Knowledge Wants to be Known:<br />

Open Access Issues for the Behavioral and Social<br />

Sciences, I discovered that open access has a friend<br />

in John Willinsky, professor of <strong>Education</strong> at<br />

Stanford. Dr. Willinsky single handedly promoted<br />

the concept, and established the Public Knowledge<br />

Project that produces software allowing other<br />

university libraries to host journals. Currently,<br />

thirty-four universities have an open access<br />

mandate. Benefits include immediate access to<br />

material, author control, and an increase in the<br />

number of times an author is cited. There were<br />

questions regarding what happens when faculty<br />

move from one institution to another. The session<br />

also included views from publishing (Alison<br />

Mudditt from Sage), and a college library (Ray<br />

English from Oberlin).<br />

Judy Luther, the moderator of the program Making<br />

the Switch from Print to Online: Why, When and<br />

How, co-authored the ARL report, The E-only<br />

Tipping Point for Journals: What’s Ahead in the<br />

Print-to-Electronic Transition Zone<br />

(http://www.arl.org/bm~doc/Electronic_Transition.pdf),<br />

a report everyone should read. One of the panelists,<br />

Elizabeth Rasmussen Martin from the University of<br />

Texas at Austin, described the difficulty of<br />

justifying the acquisition and maintenance of serials<br />

in dual formats; print and electronic. Tim Bucknell<br />

from the University of North Carolina at<br />

Greensboro indicated that online journals were less<br />

expensive, and patrons prefer them. On the<br />

publishers’ side, Noella Owen from Springer<br />

emphasized the financial benefits since online<br />

serials eliminate binding costs, storage, and<br />

shipping, and facilitate concurrent usage. Springer<br />

is exploring on-demand printing for e-books. By<br />

describing her experiences, Kim Steinle presented a<br />

slightly different picture regarding Duke University<br />

Press’ move to online material. For the most part,<br />

the Press spent more on offering online serials<br />

because of increases in and training of staff, and the<br />

need to work with new vendors. She found that<br />

there were new demands for keywords, definition of<br />

terms, and a higher level of customer service<br />

required.<br />

To explore information literacy, or IL, from a<br />

slightly different angle, I attended the session, Is<br />

there a Right to Information Literacy? Academic<br />

Responsibility in the Information Age. The session<br />

focused on policy. Patricia Stanley, Deputy<br />

Assistant Secretary, U.S. Department of <strong>Education</strong>,<br />

Office of Vocational and Adult <strong>Education</strong> talked<br />

about the responsibility of K-12 educators to make<br />

sure that high school graduates are ready for work<br />

and college. She touched on early government<br />

legislation (Perkins), and programs (Pathways), and<br />

of course mentioned No Child Left Behind. She<br />

stressed the three A’s, accessibility, accountability,<br />

and affordability, and said that IL is critical to<br />

students’ successes.<br />

Penny Beile presented the view from the frontlines<br />

as a librarian at the University of Central Florida.<br />

She talked about university policy, the course of<br />

action, and that UNESCO assigns the responsibility<br />

of IL to librarians. To illustrate how IL can become<br />

policy in a state university system, Lorie Roth,<br />

Assistant Vice-Chancellor, Academic<br />

Affairs, and Stephanie Sterling Brasley, Manager,<br />

Information Literacy Initiatives described in detail<br />

their experiences and success in instituting IL in the<br />

California State University system.<br />

In addition to making attendees feel warm and<br />

fuzzy at breakfasts, lunches, and breaks, vendors<br />

talk about their products. A case in point was the<br />

breakfast sponsored by the American Psychological<br />

<strong>Association</strong> (APA). Over steel-cut porridge, Eggs<br />

Benedict, and scones, we learned that in 2009 APA<br />

will launch a new database of educational and<br />

psychological tests available from non-commercial<br />

sources. APA representatives also talked about<br />

copyright issues regarding their well-known APA<br />

Manual, and methods to promote “green” in their<br />

workplace such as instituting flex time for their<br />

employees.<br />

I did allow myself one guilty pleasure; I attended a<br />

book talk that Jamie Lee Curtis gave to a group of<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 4

children. I love Jamie Lee, and she did not<br />

disappoint. What a smart, funny, and sharp lady.<br />

During the question and answer session, the most<br />

pressing query came from a little boy who asked<br />

how Jamie Lee bumped into her co-star, Lindsay<br />

Lohan, in order to transform herself from mother to<br />

daughter in the film, Freaky Friday. Apparently,<br />

both actresses wore padding; lots of it.<br />

Even though ALA took place in Anaheim, home of<br />

Disneyland, I did not pay a return visit to the park<br />

which I first visited when I was five years old, oh<br />

several decades ago. I didn’t want to challenge my<br />

fond memories of Frontierland, and Tomorrowland.<br />

Besides, ALA provided an amusement park of its<br />

own, complete with food, intellectual stimulation,<br />

and a simulated roller coaster ride in the exhibit<br />

hall. I had all the excitement I could take plus<br />

endless sunshine.<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> (ISSN 0148-1061) is a<br />

publication of the <strong>Education</strong> Division, <strong>Special</strong><br />

<strong>Libraries</strong> <strong>Association</strong>. It is published two times a<br />

year (Summer/Winter). Starting in 2009, current<br />

issues of <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> will be available in<br />

full-text on the SLA <strong>Education</strong> Division’s website at<br />

http://www.sla.org/division/ded/edlibs.html.<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> is indexed in Library Literature<br />

and the Current Index to Journals in <strong>Education</strong>.<br />

Permission to reprint articles must be obtained in<br />

writing from the Editors (or the original sources<br />

where noted). Opinions expressed in articles and<br />

book reviews are those of the authors and do not<br />

necessarily represent the views of the editors,<br />

Editorial Committee, or the members of the SLA<br />

<strong>Education</strong> Division.<br />

Officers of the <strong>Education</strong> Division, SLA for<br />

2008-2009: Chair: Lesley Farmer; Past Chairs:<br />

Sharon Weiner, Susan Couch; Secretary-Treasurer:<br />

Debbie Bogenschutz<br />

© 2008 – <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> <strong>Association</strong>,<br />

<strong>Education</strong> Division<br />

A Letter from our<br />

Business &<br />

Circulation Manager<br />

Thank you for your<br />

continued support of<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, the<br />

peer-reviewed journal of<br />

SLA's <strong>Education</strong><br />

Division. Originally,<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> was sent only to members of<br />

the <strong>Education</strong> Division.<br />

When we began offering paid subscriptions, our<br />

circulation increased to libraries and scholars in<br />

over 40 countries on three continents. During this<br />

period of increasing costs and stagnant budgets, we<br />

have seen a drop in subscriptions. After much<br />

deliberation, we have decided to take steps to make<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> available to a much wider<br />

global audience. Our members and subscribers will<br />

receive the Winter 2008 issue, Volume 31 (2) by<br />

email, as has been our recent practice. After that, we<br />

have decided that <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong> will be a free<br />

publication available to all through the <strong>Education</strong><br />

Division's website:<br />

http://units.sla.org/division/ded/index.html.<br />

Our editors will continue to seek, review, and<br />

publish the same great content, but the result will<br />

now be available to researchers everywhere.<br />

Volume 31 will be available at the website after a<br />

one-year embargo, as has been our policy. When<br />

Volume 32 is published, we will open the journal to<br />

all. Back issues for those volumes published<br />

electronically are now available at the website, and<br />

we will be working to bring more of the backlist<br />

online.<br />

Again, thanks for your support through the years.<br />

We have appreciated having you as subscribers, and<br />

we hope you'll enjoy our new availability.<br />

Debbie Bogenschutz, MSLS, MA<br />

Coordinator of Information Services<br />

Johnnie Mae Berry Library<br />

debbie.bogenschutz@cincinnatistate.edu<br />

513-569-1611 tel 513-559-0040 fax<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 5

Information Literacy in<br />

Real Life and in<br />

Second Life<br />

By Cybèle Elaine Werts<br />

Back in the years of yore<br />

when I was a student at<br />

Temple University, I took<br />

a batch of communications<br />

classes in pursuit of my<br />

degree in video<br />

production. In one of the more esoteric ones, we<br />

often debated the meaning of media literacy as it<br />

related to the media of the time, circa early 1980’s.<br />

Did such a concept even exist? If so, what was it,<br />

and was it even relevant to our work? At the time,<br />

the consensus was no.<br />

Today, the debate on that existence and relevance<br />

has been made moot by thirty years and a<br />

proliferation of information so vast, it’s nearly<br />

immeasurable. I was typing those youthful term<br />

papers on a portable electric typewriter which was<br />

pretty nifty at the time because it had an automatic<br />

correction function, and it is to my PC today that<br />

same vast, nearly immeasurable distance. Today,<br />

we all see the results of what we call information, or<br />

perhaps technological literacy (broadly speaking).<br />

You may not know exactly what these phrases mean<br />

yet, but they affect your ability to get a job, buy a<br />

house, pay your bills, and so much more.<br />

What is Information Literacy then? What about<br />

Media Literacy, Visual Literacy and the rest? Are<br />

they the same, part of a continuum or just some Big<br />

Amorphous Blob?<br />

Let’s look at some definitions before we move on.<br />

Just so you know, there are as many definitions for<br />

these phrases as there are students with esoteric<br />

communications degrees, so I selected the ones that<br />

are short, concise, and have an excellent<br />

provenance.<br />

Editorial<br />

Visual Literacy<br />

Based on the idea that visual images are a language,<br />

visual literacy can be defined as the ability to<br />

understand and produce visual messages. This skill<br />

is becoming increasingly important with the everexpanding<br />

proliferation of mass media in society. As<br />

more and more information and entertainment is<br />

acquired through non-print media (such as<br />

television, movies and the Internet), the ability to<br />

think critically and visually about the images<br />

presented becomes a significant skill. Visual literacy<br />

is something learned, just as reading and writing are<br />

learned. It is very important to have the ability to<br />

process visual images efficiently and understand the<br />

impact they have on viewers.<br />

~ AT&T/UCLA Initiatives for 21st Century Literacies 1<br />

Information Literacy<br />

Information Literacy is defined as the ability to<br />

know when there is a need for information, to be<br />

able to identify, locate, evaluate, and effectively use<br />

that information for the issue or problem at hand.<br />

~ National Forum on Information Literacy 2<br />

Digital Literacy<br />

Digital literacy is more than just the technical ability<br />

to operate digital devices properly; it comprises a<br />

variety of cognitive skills that are utilized in<br />

executing tasks in digital environments, such as<br />

surfing the web, deciphering user interfaces,<br />

working with databases, and chatting in chat rooms.<br />

~ Eshet-Alkali & Amichai-Hamburger 3<br />

Media Literacy<br />

Media Literacy is a twenty-first century approach to<br />

education. It provides a framework to access,<br />

analyze, evaluate and create messages in a variety of<br />

forms — from print to video to the Internet. Media<br />

literacy builds an understanding of the role of media<br />

in society as well as essential skills of inquiry and<br />

self-expression necessary for citizens of a<br />

democracy.<br />

~ Center for Media Literacy 4<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 6

Now just as a side note,<br />

and perhaps an appetizer<br />

to encourage you to read<br />

my interview with<br />

Tamara Moats on the<br />

Visual Thinking Process<br />

(VTP) which she uses in<br />

her work as a museum<br />

curator in teaching<br />

students how to see art in<br />

a new and different way. I<br />

asked her how she saw<br />

visual thinking as part of<br />

the larger scope of Information and Visual<br />

Literacies that we’re exploring here. Tamara gave<br />

me not the pedagogical definition, but one more<br />

from the heart. She said:<br />

“I see it as something that pervades all aspects<br />

of the contemplative life. Art is a reflection of<br />

society, of a people, of an individual. It is a<br />

pathway to the soul. It stimulates us to think,<br />

even for just a few minutes, in a new way, and<br />

in that sense, open new pathways in the mind….<br />

It is about the experience, either sensual or<br />

rational, and whatever message we might gain<br />

from it. The idea of visual literacy has become<br />

important currently because we are so<br />

bombarded with imagery every waking moment.<br />

It is important to become visually literate, or<br />

visually discerning, in order to survive.”<br />

I include her perspective here because it’s easy to<br />

get lost in the practical applications of all this<br />

literacy stuff, and forget that it is also entirely<br />

engaged in the way that we move through the<br />

world.<br />

With this in mind, allow me to invite you to step<br />

back a little and see if we can get a grasp on how all<br />

these concepts, definitions, and spirals of fancy<br />

come together in a real life way. One place they all<br />

come into play is in Second Life (SL) where I have<br />

recently begun my explorations<br />

through my Avatar named<br />

SuperTechnoGirl. SL is a fine<br />

example of the confluence of all<br />

these types of literacies, although<br />

perhaps not “real life” as you may<br />

define it. On the one hand, it uses a<br />

conceptual framework that<br />

allows us to look at the<br />

world of SL in a visual<br />

and spatial way as we are<br />

used to doing in real life<br />

such as walking around.<br />

For example, when you go<br />

shopping in SL, you may<br />

teleport to the store, but<br />

you’ll actually “walk”<br />

through each room of the<br />

store, just as you would in<br />

real life. This is important<br />

because we all need building blocks of the familiar<br />

before we can move on to the unfamiliar. On the<br />

other hand, SL also requires us to move through<br />

space, conduct business, and interact with other<br />

people (Avatars) in a way that is completely novel.<br />

Second Life is not simply a game where you go to<br />

play and win or lose. In fact, it’s not a game at all,<br />

and there’s nothing in particular to win or lose. Of<br />

course I’m sure that there are some people who do<br />

go there just to goof around, flirt, or maybe to spend<br />

hours designing clothing or some such. And I’m<br />

sure there are some games there as well if you were<br />

to seek them out. But let’s face it, most of us don’t<br />

have the time, interest, or motivation to spend our<br />

life that way.<br />

Think of Second Life instead as a place to do what<br />

you do in real life, but through your computer. Take<br />

me as an example, being as I’m the only one here.<br />

Aside from my interest in cool boots, I like to hang<br />

out with other writers, information professionals,<br />

and people into emerging technologies. On the one<br />

hand, just exploring SL is a shot at my goal of<br />

learning new technologies, and where better to meet<br />

those info pros than say at the <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong><br />

<strong>Association</strong> SL space? SL describes it as allowing<br />

organizations to create space for communication,<br />

collaboration and community engagement. You can<br />

hold virtual meetings and classes, construct product<br />

simulations, provide employee<br />

training and more.<br />

There is also real business being<br />

transacted (I’ve spent about $20 US<br />

so far, which actually buys quite a lot<br />

there), visited a number of stores that<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 7

most definitely do not exist in<br />

Vermont, and sat on a<br />

beautiful beach and watched<br />

the waves crash against my<br />

wicker chair as I listened to<br />

the sounds of the surf. Is it all<br />

imaginary? Well, it depends<br />

on how philosophical you<br />

want to get. Ideas and information aren’t “real” in<br />

the sense of being concrete, but they are certainly<br />

authentic enough. Second Life is another place –<br />

although not a traditional “place” as we generally<br />

define it – to explore, live, learn, and play. It is<br />

another reality that is as existent as ideas and<br />

creativity, and of course if you have the right skills<br />

– as with all things – there’s money to be made.<br />

Let’s talk a little about how Information and the<br />

other literacies come into play here because I’ll tell<br />

you, SL actually is rather a challenge to learn, and if<br />

I didn’t have all of my literary ducks in a row, I<br />

would have long since given up. (I still sometimes<br />

consider it.)<br />

Visual Literacy in SL<br />

SL is almost completely a visual medium, although<br />

of course if you’re a wee bit tech-savvy, friends can<br />

chat with you by voice (microphone and speaker),<br />

or through digital transformations of their typed<br />

words. The downside of this intensely visual side of<br />

things is that often as in life, how we look is<br />

unfortunately almost more important than who we<br />

are. In my first few discussions with various SL<br />

participants, I heard more comments about my lack<br />

of taste in hair and clothing than I ever heard about<br />

who I was, what I did for a living, or anything else<br />

that actually means anything. The interesting thing<br />

is that in the real world, I’m sure these same people<br />

would never have the nerve to criticize<br />

me out loud. I’m almost thinking I’d<br />

rather live in real life and not hear it<br />

when it comes to this, but whatever.<br />

I was annoyed as you can imagine,<br />

although I had a vague feeling it had<br />

something to do with that “you’re in or<br />

you’re out” group mentality. I was<br />

clearly “new” so I also was clearly “out”<br />

with some groups where that was<br />

important (not groups where I was likely<br />

What is Information Literacy then?<br />

What about Media Literacy, Visual<br />

Literacy and the rest? Are they the<br />

same, part of a continuum or just<br />

some Big Amorphous Blob?<br />

to return). Although I gave<br />

it back to the Nasty Parkers<br />

with a few choice remarks, I<br />

nevertheless felt a bit<br />

embarrassed that I’d entered<br />

a universe where the clothes<br />

available were considered<br />

Goodwill leavings. I trotted<br />

off to do some shopping and picked up some<br />

groovy duds, which fortunately are pretty darn<br />

cheap in a virtual world. And yes, you do pay real<br />

money even for virtual clothing unless you have the<br />

skills to design them, which I do not. Of course you<br />

can also earn money in SL which are called Linden<br />

Bucks, but that’s a whole other discussion.<br />

Aside from my petty grumbling, the broader<br />

implications of this are actually quite interesting.<br />

My Avatar – SuperTechnoGirl – looks like a more<br />

hard-bodied version of me, except with red hair<br />

which I always wished I had. I wasn’t aiming for<br />

anything exotic. In SuperTechnoGirl is a lot of me<br />

(Cybèle), and some of who I want to be: a tough gal<br />

with rippled abs. (Try not to laugh!). In truth, nearly<br />

everyone online is not only fabulously gorgeous,<br />

has spectacular clothing, sports killer hair, and is –<br />

of course - thin. Look around you now – how many<br />

people are like that? No, I mean really! The ones<br />

who aren’t those things usually have Avatars who<br />

are exotic animals from Mars or something of the<br />

sort. SL allows us to be anyone we want, which is<br />

fun, but also means that there are none of the limits<br />

of real life. When I look at the people I’m meeting<br />

and speaking with, I can’t help but wonder how<br />

much of their Avatar is really them (as I am Cybele)<br />

and how much is who they want to be (the abs).<br />

And also, is your fantasy self (Say if I wanted to be<br />

Tank Girl for a day) any less real than my little<br />

fantasy about being more buff? Try to<br />

figure out that little philosophical<br />

conundrum. Of course, when you think<br />

about it, we all kind of got stuck with the<br />

looks and bodies we were born with, and<br />

how we look may well have zip to do<br />

with who we are anyway. The result is<br />

that we can’t really trust anything we see<br />

or hear from another person in SL,<br />

relative to how many of us see “truth” in<br />

everyday life. It’s all a little squirrelly<br />

don’t you think?<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 8

Visual Literacy extorts us to think critically about<br />

what we see, and attend to learning about the<br />

environment in which we are moving through. It<br />

asks us to process visual images efficiently and<br />

understand the impact they have, because in places<br />

like SL, not doing so nets you a whole lotta nothing.<br />

Come to think of it, not doing so in real life nets<br />

you a whole lotta nothing as well.<br />

Information Literacy in SL<br />

Information Literacy asks us to identify, locate,<br />

evaluate, and effectively use the information we<br />

need. In the world of SL, this is a pretty big<br />

stipulation, because it’s not just about getting a<br />

better “Do” or a really terrific pair of boots. In<br />

navigating around, there is, for example, the simple<br />

act of moving your Avatar from one place to<br />

another, either by walking, flying, and even<br />

teleporting – my favorite method because it’s pretty<br />

much Captain Kirk’s Transporter. How do you learn<br />

to walk, fly, or teleport? Where is that information?<br />

I ask because in SL there is the website<br />

(http://secondlife.com/ ) which has all kinds of<br />

information and help, but then there’s also the<br />

actual software Second Life which is a completely<br />

separate application which you install and run when<br />

you want to travel in. Yup, it took me a while to get<br />

this one straight, and both of them offer help and<br />

advice in completely different ways.<br />

Locating the right information and translating that<br />

to the situation at hand has not always been an easy<br />

task. Walking, flying and<br />

teleporting I got. Buying a<br />

snazzy outfit I even got,<br />

although it took a fair bit<br />

longer than browsing the<br />

real life Silhouettes online<br />

catalogue. But I still<br />

haven’t figured out why the<br />

hair I bought in SL has a<br />

big bald spot in the back,<br />

and how to fix that. The<br />

reason I can’t fix that is<br />

because the seller sent me a<br />

document on correcting the<br />

problem, but I can’t figure<br />

out how to download the<br />

document, presuming that I<br />

even have the capacity to undertake the operation –<br />

whatever it is. Oh, and then there’s the problem that<br />

I can’t reply directly to e-mails from the seller via<br />

SL. It’s so frustrating that I’ve given up until I can<br />

suck up enough caffeine one morning to cope with<br />

it. Translation: my Information Literacy for Second<br />

Life is on an exceedingly slow learning curve. I<br />

know I have the need; I have more or less identified<br />

and located the information required (about the<br />

hair), but I can’t effectively use it. As to evaluating,<br />

well that’s a place to teleport to another day<br />

entirely.<br />

Digital Literacy in SL<br />

Here’s the good part: I’m pretty down with Digital<br />

Literacy; which is a blessing from the CyberGods<br />

after that soap opera with the hair. If there is<br />

anything I can do, it’s “executing tasks in digital<br />

environments, such as surfing the web, deciphering<br />

user interfaces, working with databases, and<br />

chatting in chat rooms.” On the chat room side I had<br />

a few interesting experiences, mostly in that people<br />

were about as interested in me as they were in real<br />

life; meaning that they pretty much could care less.<br />

Ongoing “chats” in the various places I visited was<br />

pretty much the same as any chat room you might<br />

visit in ten thousand places on the Internet: silly,<br />

flirtatious conversation that overlaps and generally<br />

makes little sense. Lots of “insider” comments<br />

which also make no sense. The only real difference<br />

is that I could see everyone standing around in cool<br />

outfits, leaning against brick walls with a James<br />

Dean attitude. Some even smoked. I wonder if they<br />

get cyber lung cancer?<br />

And as I mentioned, one<br />

hundred percent of the<br />

people in the rooms I<br />

visited were visually<br />

stunning in one way or<br />

another. If that isn’t the<br />

key to know how much is<br />

imaginary, I don’t know<br />

what is. I will say that a<br />

few (a very few) friendly<br />

souls chatted with me and<br />

sent me a variety of items,<br />

including skins (I think<br />

that’s hair or clothing or<br />

something), landscapes<br />

(places to visit) and of<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 9

course lots of recommendations for clothing and<br />

hair stores.<br />

I’ve always been proud of my ability to learn new<br />

applications fairly quickly, and I think I’m doing<br />

pretty well with SL in general. What I am reminded<br />

to do is to use my skills, not so much to struggle<br />

through the morass myself, but rather to research<br />

the Internet for some training in Second Life. Note<br />

to Self: Contact the SLA group in SL for advice.<br />

After all, if my sister librarians can’t help me, who<br />

can?<br />

Media Literacy in SL<br />

If Media Literacy is not a stale conversation from<br />

the 1980’s, what is it? On the other hand, the<br />

definition of Media Literacy does specify “twentyfirst<br />

century approach,” and my days at Temple<br />

were definitely in the old 20 th century. Perhaps then<br />

it translates, for example, into the recent two-part<br />

free training sessions that the <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong><br />

<strong>Association</strong> (SLA) and Click University hosted<br />

using WebEx (webcasts) and then a live session in<br />

Second Life. That’s the new millennium part of<br />

Media Literacy we can get down with. The “media”<br />

part of this literacy is the variety of ways that we<br />

have to learn now, whether it be those webcasts or<br />

live SL sessions, podcasts, video clips, online<br />

training modules, or even – gasp – old fashioned<br />

printed documents like I’m hand editing in bleeding<br />

red ink right now. How tres passé! The most<br />

important part of every tool however, is how it is<br />

matched to the need. Yes, I like to edit my own<br />

stuff on paper with red ink<br />

– just like editors did in the<br />

good old days. But no, that<br />

sure doesn’t work when<br />

you’re editing a journal<br />

with a co-editor. When I<br />

send things to my co-editor<br />

Jacqueline, it is of course<br />

always electronic.<br />

Then as now I see<br />

resistance to these changes<br />

even in my own workplace.<br />

Colleagues want their work<br />

methods to stay the same, to<br />

stay as it was when we were<br />

typing on that nifty portable<br />

electric typewriter. They sigh when I remind them<br />

to use the Adobe Connect webcast application<br />

because “a conference call and a PowerPoint<br />

presentation would have done.” It may have done<br />

indeed – for now. But they are not seeing the big<br />

picture, which is that moving ahead with media and<br />

technological literacy is a mandate in our work (not<br />

to mention a big money saver). If we loll in the<br />

ways of conference calls and PowerPoint<br />

presentations that grew from templates we’ve all<br />

seen a thousand times – as comfy a place as that is –<br />

our competition will soar above us as in Second<br />

Life, and we will watch as our American dollars<br />

transform into Second Life Linden Bucks in the<br />

blink of an accountant’s eye. Linden Bucks may be<br />

great in SL, but they aren’t going to pay my<br />

mortgage.<br />

Continuum or just big Amorphous Blob<br />

So what is it all then, a Continuum or just one big<br />

Amorphous Blob? Considering how much these<br />

literacy concepts are changing, not to mention that<br />

each is defined in enough ways to confuse even the<br />

best of information professionals, I vote for<br />

Amorphous Blob. Even with that, there remains a<br />

mandate for all of us to hop on the Information<br />

Highway, or rather teleport out to Second Life – if<br />

you’d like to join me – and leave the conference call<br />

PowerPoint presentations and my portable<br />

typewriter in the closet for a rainy day. After all you<br />

never know when they might come handy (even my<br />

computer has crabby days).<br />

I’ve been thinking lately of<br />

teleporting via Second Life<br />

back to my communications<br />

class at Temple University<br />

and chatting up that young<br />

girl who was me about all<br />

the fun stuff that’s<br />

happening these days in<br />

Media Literacy, but she<br />

probably wouldn’t believe<br />

me. After all, even the 1984<br />

dawn of the Macintosh was<br />

still a year away. But then<br />

even SL doesn’t allow for<br />

time travel as far as I know.<br />

Still, teleporting around as<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 10

in “Beam Me Up Scottie” has always been a dream<br />

of mine, so if I can’t do it here in Vermont, at least<br />

SuperTechnoGirl can do it on the Isle of<br />

Tranquility. One of my favorite experiences was<br />

when I flew over the island and spotted a water<br />

fountain with two glistening unicorns. I spent about<br />

half an hour figuring out how to hop up on one and<br />

sit down – kind of sidesaddle was the best I could<br />

do. But once I got there I have to admit, it was a<br />

beautiful place. It’s that kind of view that brings me<br />

back to Second Life. Fortunately, SuperTechnoGirl<br />

has more Information Literacy in her little finger<br />

than I ever had in my whole arm; although I’m not<br />

so sure about the hair.<br />

References<br />

1. "Media Literacy Definition Matrix." Leadership<br />

Summit Toolkit 2007 30 Sep 2008<br />

.<br />

2. Ibid<br />

3. Ibid<br />

4. "Visual Literacy." AT&T/UCLA Initiatives for 21st<br />

Century Literacies 06/20/2002 20 Sep 2008<br />

http://www.kn.pacbell.com/wired/21stcent/visual.html<br />

Other Resources<br />

Second Life<br />

Second Life ® is a 3-D virtual world created by its<br />

Residents. Since opening to the public in 2003, it has<br />

grown explosively and today is inhabited by millions of<br />

Residents from around the globe. From the moment you<br />

enter the World you'll discover a vast digital continent,<br />

teeming with people, entertainment, experiences and<br />

opportunity. Once you've explored a bit, perhaps you'll<br />

find a perfect parcel of land to build your house or<br />

business. You'll also be surrounded by the Creations of<br />

your fellow Residents. Because Residents retain<br />

intellectual property rights in their digital creations, they<br />

can buy, sell and trade with other Residents. The<br />

Marketplace currently supports millions of US dollars in<br />

monthly transactions. This commerce is handled with the<br />

inworld unit of trade, the Linden dollar, which can be<br />

converted to US dollars at several thriving online Linden<br />

dollar exchanges.<br />

http://secondlife.com/<br />

SLA in Second Life Blog<br />

Sharing learnings and initiatives around SLA in Second<br />

Life.<br />

http://sla-divisions.typepad.com/sla_in_second_life/<br />

Tank Girl – the Film<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tank_Girl_(film<br />

Information Literacy Competency Standards for<br />

Higher <strong>Education</strong><br />

These standards were reviewed by the ACRL Standards<br />

Committee and approved by the Board of Directors of<br />

the <strong>Association</strong> of College and Research <strong>Libraries</strong><br />

(ACRL) on January 18, 2000, at the Midwinter Meeting<br />

of the American Library <strong>Association</strong> in San Antonio,<br />

Texas. These standards were also endorsed by the<br />

American <strong>Association</strong> for Higher <strong>Education</strong> (October<br />

1999) and the Council of Independent Colleges<br />

(February 2004)<br />

Read a full version of the standards<br />

http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/standards.pdf<br />

The Standards Are:<br />

1. The information literate student determines the<br />

nature and extent of the information needed.<br />

2. The information literate student accesses needed<br />

information effectively and efficiently. Standard<br />

Three<br />

3. The information literate student evaluates<br />

information and its sources critically and<br />

incorporates selected<br />

4. information into his or her knowledge base and<br />

value system.<br />

5. The information literate student, individually or<br />

as a member of a group, uses information<br />

effectively to accomplish a specific purpose.<br />

6. The information literate student understands<br />

many of the economic, legal, and social issues<br />

surrounding the use of information and accesses<br />

and uses information ethically and legally.<br />

Reference:<br />

http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/inform<br />

ationliteracycompetency.cfm<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 11

Information Literacy for Teaching and Learning: A Course for Teacher Practitioners<br />

By Sara Bushong and Colleen Buff<br />

21 st Abstract<br />

Teachers are faced not only with standards-based instructional design daily, but with<br />

Century<br />

the shortage of certified school library media specialists within their districts.<br />

Literacies<br />

Information Literacy for Teaching and Learning, a graduate level course, was created, in<br />

part, to empower teachers with the knowledge, skills and abilities to embed information literacy within<br />

classroom learning experiences. In addition, the skills mastered and activities explored in this course<br />

logically transfer to research projects assigned in future graduate courses.<br />

Introduction<br />

Most children in today’s PreK-12 learning<br />

environment have grown up with the Internet and<br />

a mind-boggling amount of information available<br />

to them via their computers. Even so, this does not<br />

make them computer or information literate.<br />

These are skills that students need time to learn,<br />

practice, and develop throughout all levels of their<br />

education. Unfortunately, teachers are in the<br />

position of having to learn these skills as well,<br />

since many of them did not grow up in a dynamic,<br />

electronic information age. Because being<br />

information literate does not reside in any one<br />

discipline, there is often no one particular person<br />

in the school setting to whom this responsibility<br />

should fall. Rather, these are skills that cross<br />

boundaries and therefore whether or not these<br />

competencies are part of the standards-based<br />

education system should be a concern to all<br />

educators.<br />

This is a case study that explains one attempt to<br />

provide graduate-level instruction to teacher<br />

practitioners interested in working independently<br />

or in collaboration with their school library media<br />

specialist to integrate the instruction of<br />

information literacy into their PreK-12 teaching.<br />

Review of the Literature<br />

A review of the literature<br />

reflects that at many<br />

institutions in the United<br />

States and Canada, library<br />

and information literacy<br />

Articles<br />

instruction is embedded in the pre-service teacher<br />

preparation programs at the undergraduate level<br />

(Battle, 2007; Johnson & O’English, 2003;<br />

Naslund, Asselin, & Filipenko, 2005; O’Hanlon,<br />

1988; Witt & Dickinson, 2003). A study of one<br />

such undergraduate approach concludes that preservice<br />

teachers are not effectively learning about<br />

school library programs and information literacy<br />

pedagogy (Asselin & Doiron, 2003). Although<br />

stand-alone courses on information literacy<br />

competencies likely exist at the graduate level, the<br />

authors were not able to identify any documented<br />

analysis of this approach in the professional<br />

literature.<br />

Rationale for Starting the Course<br />

The pre-service teacher education curriculum at<br />

Bowling Green State University (BGSU) is<br />

rigorous in an attempt to satisfy the National<br />

Council for Accreditation of Teacher <strong>Education</strong><br />

(NCATE) 2008 accreditation demands and in<br />

order to prepare future teachers to incorporate a<br />

variety of academic content standards at the state<br />

and national levels into student learning<br />

experiences (Ohio, 2008). In short, there is no<br />

room in the pre-service undergraduate curriculum<br />

to offer a stand-alone course on information<br />

literacy. This is not to say that there is not a place<br />

for information literacy concepts in the<br />

undergraduate education<br />

curriculum. In fact,<br />

information literacy<br />

experiences are strategically<br />

and systematically integrated<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 12

throughout the undergraduate teacher preparation<br />

program at BGSU. After closely examining the<br />

undergraduate and graduate level curriculum, it<br />

was evident that there was more flexibility in the<br />

graduate curriculum to absorb a new course<br />

offering and ultimately take information literacy<br />

skills development to the next level.<br />

Since BGSU offers a Masters in <strong>Education</strong>, it<br />

seemed the perfect place to suggest an elective,<br />

stand-alone course devoted to information literacy.<br />

The rationale was that teacher practitioners would<br />

already possess relevant classroom experience,<br />

established teaching practices and be interested in<br />

creating new research activities to enhance their<br />

teaching as well as their students’ learning<br />

experiences. Additionally, with the shortage of<br />

certified school library media specialists in many<br />

school districts around the state, there was a need<br />

to empower classroom teachers with the<br />

knowledge, skills, and abilities to teach<br />

information seeking behaviors. Three to four<br />

sections of the course are offered over six weeks<br />

during the summer session. Instructors are<br />

librarians within the BGSU University <strong>Libraries</strong><br />

system and are uniquely qualified to design and<br />

deliver course material. Instructor experience<br />

includes undergraduate degrees in education,<br />

graduate degrees in education, and successful<br />

PreK-16 teaching experience. Given the complex<br />

nature of the cooperative library system in the<br />

state of Ohio, it is critical that academic librarians<br />

with a solid understanding of each of the three<br />

systems maintain the responsibility for teaching<br />

this course. It is a full-time job keeping abreast of<br />

the changes in these cooperatives, a responsibility<br />

that would be overwhelming for an education<br />

faculty member to handle.<br />

The course description<br />

builds upon the definition<br />

of information literacy as<br />

the ability to locate,<br />

evaluate and effectively use<br />

information resources as<br />

fundamental for student<br />

success in grades PreK-12<br />

and beyond. The course<br />

focuses on examining and<br />

promoting lifelong<br />

information literacy skills and instructional<br />

models useful when crafting effective research<br />

assignments. Students explore online, print and<br />

non-print information resources available in<br />

public, school and academic settings. Emphasis is<br />

placed on critical thinking, resource analysis,<br />

standards research (local, state and national in<br />

scope) and the ethical use of information.<br />

Readings, skills mastered and activities explored<br />

in this course logically transfer to research<br />

projects in subsequent graduate courses and<br />

extend to real-life applications in the PreK-12<br />

classroom.<br />

Student learning outcomes for the course<br />

include the following components:<br />

• Students will gain an understanding of the<br />

organizational structure of print, non-print<br />

and electronic information resources.<br />

• Students will be able to determine the<br />

scope of an information tool during the<br />

selection process.<br />

• Students will explore and master the<br />

intricacies of search strategies for<br />

application in any research environment.<br />

• Students will be able to create effective<br />

learning experiences for PreK-12 students<br />

that integrate the research process into the<br />

curriculum.<br />

About the Course<br />

Ohio has a complex system of multiple library<br />

cooperatives that consist of three divisions: public,<br />

PreK-12, and higher education. The public library<br />

cooperative is called the Ohio Public Library<br />

Information Network (OPLIN, 2007). The PreK-<br />

12 system is known as The Information Network<br />

for Ohio Schools, INFOhio<br />

(2008) and the system for<br />

higher education is known as<br />

the Ohio Library and<br />

Information Network<br />

(OhioLINK, 2008). Although<br />

there is some cooperation and<br />

resource sharing among these<br />

three entities, the mission of<br />

each is specifically geared<br />

towards the needs of their<br />

respective populations.<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 13

The structure of the course touches upon the<br />

resources provided by each of the three statewide<br />

cooperatives, with an emphasis on resources<br />

specific to teaching students PreK-12, but the<br />

skills teachers need to be information literate as<br />

graduate students are also addressed.<br />

From the onset, the course was designed to be<br />

practical. Each project was strategically designed<br />

in such a way that the teachers would be able to<br />

incorporate the end products in their classrooms<br />

with their students. Mechanisms have been created<br />

to share the reviewed work of the teachers with<br />

other educators throughout the state of Ohio.<br />

Feedback received over the years indicated that<br />

this sharing creates added value among the<br />

teachers because much of their graduate studies<br />

have taken a more theoretical approach.<br />

The course begins with an indepth<br />

overview of the structure<br />

of the information<br />

environment, an examination<br />

of the multiple definitions of<br />

information literacy, and the<br />

concept of transferable research<br />

skills from one online<br />

environment to the next. For<br />

most students it is the first time<br />

they have been asked to<br />

consider information retrieval in the context of the<br />

teaching and learning environment. In addition to<br />

understanding how information is organized on a<br />

large scale, students are introduced to general<br />

research concepts that are utilized in most online<br />

environments such as how to conduct keyword<br />

searches, when to use Boolean operators, and what<br />

truncation searches accomplish. Students practice<br />

the use of these search skills at length and are<br />

asked to intentionally use the skills throughout the<br />

course.<br />

The second module in the course includes an<br />

examination of the various information literacy<br />

models and the different standards expected to be<br />

incorporated into the projects throughout the<br />

course. In the first part of this module, the Big6 TM<br />

research model, created by Robert Berkowitz and<br />

Mike Eisenberg, is explored. According to their<br />

website, “Big6 is the most widely known and<br />

widely-used approach to teaching information and<br />

technology skills in the world.” (Big6 overview,<br />

2008) This research model is demonstrated in the<br />

course by using the example of purchasing a new<br />

automobile and includes research terminology<br />

familiar to educators. Students participate in an<br />

activity to compare and contrast additional<br />

research and information literacy models, and are<br />

challenged to consider adopting a particular model<br />

for students to use in their own classroom, thus<br />

seamlessly integrating information literacy<br />

principles into instruction. As each teacher’s<br />

school environment and access to library support<br />

differs dramatically, the benefits of having an<br />

entire grade, school or even school district adopt a<br />

particular model is discussed.<br />

For the second part of this module, students work<br />

intensively with the Ohio Academic Content<br />

Standards (Ohio, 2008). Through<br />

a hands-on, small group activity,<br />

students look for the presence of<br />

information literacy competencies<br />

in the academic content areas,<br />

technology standards and library<br />

guidelines, and then sort them<br />

strategically within the Big6 TM<br />

categories. Areas of overlap as<br />

well as deficiencies are identified<br />

and students examine approaches<br />

to addressing information literacy in<br />

interdisciplinary ways. Students are also<br />

introduced to the American <strong>Association</strong> of School<br />

Librarian’s Standards for the 21 st Century Learner<br />

(AASL, 2008), the Nine Information Literacy<br />

Standards for Student Learning (AASL, 1998) and<br />

the Information Literacy Competency Standards<br />

for Higher <strong>Education</strong> from the <strong>Association</strong> of<br />

College and Research <strong>Libraries</strong> (ACRL, 2008).<br />

By the third module, the final project is unveiled.<br />

At the end of the course, students are expected to<br />

build a WebQuest, which is an inquiry-based<br />

lesson in which most of the content utilizes online<br />

resources (Dodge, 2007.) This approach was<br />

popularized by Bernie Dodge at San Diego State<br />

University, and is utilized because of the model’s<br />

close alignment with information literacy<br />

competencies and research seeking behaviors. The<br />

rationale for using this model as a final project is<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 14

that it is an excellent mechanism for students to<br />

synthesize all of the resources they are exposed to<br />

in the course and to apply them to a real world<br />

learning experience for their students. Students in<br />

the course have significant latitude in how to<br />

construct their WebQuest. Because most of the<br />

students have little, if any, experience with web<br />

authoring tools such as Dreamweaver or Microsoft<br />

FrontPage, Microsoft PowerPoint was chosen as<br />

the application of choice because it is familiar to<br />

most students as well as usually supported by most<br />

school systems. A template was constructed in<br />

Microsoft PowerPoint which includes the primary<br />

components and framework for their WebQuest:<br />

Introduction, Task, Resources, Process,<br />

Evaluation, and Conclusion. In addition, the<br />

typical structure of a WebQuest has been slightly<br />

modified to include the components of Standards,<br />

Citations, and Teacher Notes to the framework.<br />

In the next module, students are oriented to the<br />

INFOhio resources which include approximately a<br />

dozen different databases, most of which are<br />

available in each school district within the state of<br />

Ohio as well as remotely. Resources are available<br />

for a variety of content areas and all grade levels.<br />

Although all teachers theoretically have access to<br />

the network in the state of Ohio via their school<br />

districts, for many of them, this is the first time<br />

they have either been exposed to these resources<br />

or have devoted time to exploring the contents and<br />

classroom applicability of the resources. A tenminute<br />

learning activity is assigned at this point.<br />

In this exercise students create a mini-tutorial that<br />

will train their students and/or colleagues in one of<br />

the INFOhio databases to answer a specific<br />

research question. All tutorials are expected to<br />

include the following elements: the database<br />

name, grade level, topic/subject area, essential<br />

question, applicable academic content standards,<br />

search steps, additional comments or helpful hints<br />

about how the database works. Students are<br />

required to develop the essential research question<br />

in this tutorial assignment in such a way that it fits<br />

in with the final WebQuest project. Examples of<br />

the learning activities are housed on the Educator<br />

page from the INFOhio website (INFOhio teacher,<br />

2008).<br />

Because not all PreK-12 students have computer<br />

access at home, and because schools are not open<br />

during evening hours, instructors are intentional<br />

about including the statewide public library<br />

consortium, the Ohio Public Library Information<br />

Network (2007.) Any resident of Ohio may obtain<br />

a library card that enables users to access many of<br />

the online sources available through this<br />

consortium from remote locations. While there is<br />

some overlap in the online offerings between<br />

OPLIN and INFOhio, there are unique offerings as<br />

well. Students in the course are given activities<br />

and time to explore the wealth of resources in<br />

OPLIN, and they are encouraged to incorporate<br />

these findings into their final WebQuests.<br />

The module on Effective Internet Searching<br />

changes frequently due to the volatile nature of the<br />

Internet. Students learn about search engine math<br />

and logic as well as the different types of<br />

searching tools such as search engines, directories,<br />

and meta search engines. In addition to exploring<br />

the advanced search features of Google, students<br />

are provided the opportunity to learn about, utilize<br />

and compare functionalities between other search<br />

engines such as Ask.com and Dogpile.com.<br />

In aligning the course structure with the tenants of<br />

information literacy competencies, a module is<br />

included on the ethical and responsible use of<br />

information and explores the topics of plagiarism<br />

and copyright infringement. This is an<br />

increasingly popular topic because instances of<br />

plagiarism have been and continue to be on the<br />

rise (McCabe, 1999). Teachers struggle with<br />

methods to detect and prevent acts of academic<br />

dishonesty. This class provides concrete strategies<br />

with the added benefit of meeting regularly with a<br />

group of professionals with whom they can<br />

exchange ideas and strategies to combat this<br />

problem. The notion that teaching ethical use of<br />

information is the responsibility of the English<br />

composition teacher at the high school level is<br />

dispelled. Everyone is encouraged to embrace this<br />

problem as well as model ethical use of<br />

information and multimedia in their teaching<br />

practices.<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 15

As graduate students, teacher practitioners<br />

struggle with utilizing academic resources to<br />

search for research-based articles and monographs<br />

required for courses taken prior to this one and for<br />

upcoming classes. An academic resources module<br />

was created to address these concerns as students<br />

had repeatedly commented that this course was<br />

needed earlier in their program<br />

of study. Subject, keyword and<br />

title searching of books and<br />

multimedia resources are<br />

introduced through the BGSU<br />

(2008) online catalog and the<br />

central OhioLINK (OhioLINK<br />

library, 2008) catalog during<br />

Part One of this module. Part<br />

Two introduces students to the<br />

wealth of resources available<br />

through research databases<br />

purchased locally and<br />

cooperatively within<br />

OhioLINK. Students are<br />

unfamiliar with the notion of fee-based and free<br />

resources available through Internet browsers, and<br />

this becomes another opportunity to draw attention<br />

to the differences between the two and the benefits<br />

of the breadth of scholarship available through the<br />

fee-based databases. ERIC and <strong>Education</strong><br />

Research Complete are demonstrated and students<br />

participate in activities designed to increase their<br />

content knowledge and search strategies. During<br />

the final part of this module, students practice<br />

citing resources (print, electronic and Internet)<br />

using the APA citation style. This is particularly<br />

useful within this course for the citation section of<br />

the WebQuest as well as in future classes that<br />

require research papers.<br />

Final projects are presented to the entire class<br />

during the last day of the course. The teachers<br />

enjoy sharing their work with their colleagues, and<br />

the instructors have an opportunity to view the<br />

overall functionality, design and subject content of<br />

the WebQuest as they are projected for all to<br />

review. Students are encouraged to use the<br />

projects with students in the fall, and the most<br />

accomplished WebQuests are posted on the<br />

Information Literacy WebQuests website<br />

(WebQuests, 2008).<br />

Recently, the course was adapted to include<br />

practical uses of Internet 2.0 technologies as a<br />

mechanism to foster student-to-student and<br />

student-to-teacher collaboration by utilizing social<br />

networking tools for educational purposes. This<br />

module provides an overview of the different<br />

types of Internet 2.0 technologies while offering<br />

hands-on practice with contributing<br />

to a class wiki and class blog.<br />

Students were asked to read a series<br />

of articles on social networking and<br />

the instructional design effects of<br />

Internet 2.0 technologies. The next<br />

step was to respond to the readings<br />

via a discussion board prompt<br />

within Blackboard, the campus<br />

course management system.<br />

Responses indicated that in-service<br />

teachers recognize the need to stay<br />

abreast of the new technologies and<br />

to engage their students in learning<br />

activities to prepare them for the<br />

challenges and opportunities presented in online<br />

environments.<br />

Results and Further Research<br />

The work products generated by the graduate<br />

students in this course are far reaching. They have<br />

the opportunity to improve their personal<br />

information literacy skills while building grade<br />

and content appropriate materials to improve the<br />

information literacy skills of their students.<br />

Additionally, students are helping to connect<br />

resources with teaching and learning. A teacher’s<br />

work day is hectic and all-consuming with little<br />

time left at the end of the day to explore<br />

information resources. The course Information<br />

Literacy for Teaching and Learning affords<br />

teachers the opportunity to discover new resources<br />

to enhance the classroom experience.<br />

To view the work products of students enrolled in<br />

sections of this course, visit the following links.<br />

• Information Literacy WebQuests -<br />

http://www.bgsu.edu/colleges/library/crc/page38734.html<br />

(WebQuests, n.d.)<br />

• 10 Minute Learning Activities -<br />

http://infohio.org/Educator/LearningActivities.html<br />

(INFOhio teacher, 2008.)<br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>Libraries</strong>, Volume 31, No. 2, Winter 2008 16

Exit surveys and informal conversations with<br />

students indicate that at the conclusion of the<br />

course there is a much greater awareness of online<br />

resources available through INFOhio, OPLIN and<br />

OhioLINK; they have begun to master the idea of<br />

transferable research strategies; and they were able<br />

to create an inquiry-based activity using a familiar<br />

software application.<br />

Over the six years the class has been offered,<br />

patterns have emerged worth noting. While<br />

teachers’ comfort level with the technology seems<br />

to have improved, many continue to be unaware of<br />

all of the educational information resources<br />

available to them through the library cooperative<br />

systems. The students consistently respond that<br />

the course allows them the space in their busy<br />

professional lives to be reflective about<br />

information and technology use in the classroom.<br />

Evaluative comments include:<br />

• Activities were beneficial for use in my<br />

classroom<br />

• Assignments and lessons related to<br />

classroom—very helpful!<br />

• Very applicable to my teaching.<br />

• Course content was meaningful and useful.<br />

Assignments were practical and<br />

reasonable.<br />

• Very practical. We were able to adapt the<br />

projects to something we could use in the<br />

classroom.<br />

• This course was the most effective class I<br />

have taken so far in my full year in this<br />

cohort.<br />

• This course should be the first class. All<br />

the information would have been useful at<br />

the beginning of the program.<br />

• This course should be taken by ALL M.Ed<br />

(Masters of <strong>Education</strong>) students.<br />

Future research plans include a follow-up<br />

assessment with teachers who have been through<br />

the class to determine the skills most utilized from<br />

the course and how it has changed the way they<br />

teach. Multiple sections of the course have been<br />

offered since 2003, reaching over 400 teacher<br />

practitioners in the northern region of Ohio. With<br />

this data, the co-authors will be better prepared to<br />

showcase the merits of this course to other<br />

Masters of <strong>Education</strong> programs around the state of<br />

Ohio. If universities in other regions of Ohio were<br />

to offer a similarly structured course, the potential<br />