the explorers journal the climate change issue - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal the climate change issue - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal the climate change issue - The Explorers Club

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

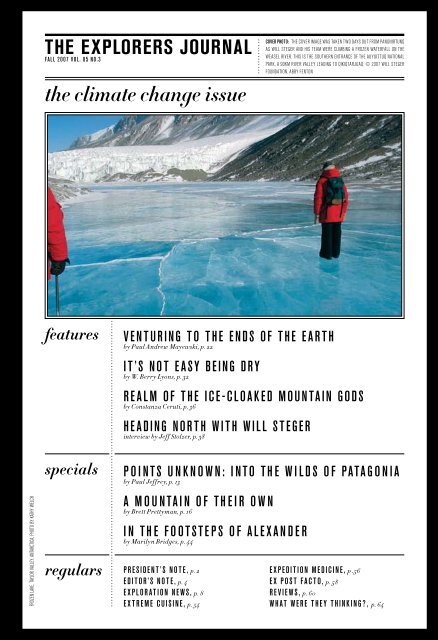

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

fall 2007 vol. 85 no.3<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> <strong>issue</strong><br />

cover photo: <strong>the</strong> cover image was taken two days out from Pangnirtung<br />

as will steger and his team were climbing a frozen waterfall on <strong>the</strong><br />

Weasel River. This is <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn entrance of <strong>the</strong> Auyuittuq National<br />

Park, a 90km river valley leading to Qikiqtarjuaq. © 2007 Will Steger<br />

Foundation, Abby Fenton<br />

features<br />

Venturing to <strong>the</strong> Ends of <strong>the</strong> Earth<br />

by Paul Andrew Mayewski, p. 22<br />

It’s not Easy Being Dry<br />

by W. Berry Lyons, p. 32<br />

Realm of <strong>the</strong> ice-cloaked mountain gods<br />

by Constanza Ceruti, p. 36<br />

heading north with Will Steger<br />

interview by Jeff Stolzer, p. 38<br />

frozen lake, Taylor valley, Antarctica, Photo by kathy welch<br />

specials<br />

regulars<br />

Points Unknown: Into <strong>the</strong> wilds of Patagonia<br />

by Paul Jeffrey, p. 13<br />

A M o u nta i n o f Th e i r O w n<br />

by Brett Prettyman, p. 16<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Footsteps of Alexander<br />

by Marilyn Bridges, p. 44<br />

president’s note, p. 2<br />

editor’s note, p. 4<br />

exploration news, p. 8<br />

extreme cuisine, p. 54<br />

expedition Medicine, p .56<br />

ex Post Facto, p. 58<br />

reviews, p. 60<br />

what were <strong>the</strong>y thinking?, p. 64

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

fall 2007<br />

president’s letter<br />

A pivotal point in our history<br />

During our successful 2007 <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Annual Dinner, which<br />

highlighted major advances in polar exploration, Paul Andrew Mayewski<br />

gave a captivating presentation on <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> in Greenland. In <strong>the</strong><br />

weeks that followed, I could not help but think about <strong>the</strong> topic, knowing<br />

that so many members of our <strong>Club</strong> have been involved in <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong><br />

research. Among our members are some of <strong>the</strong> world’s most recognized<br />

experts in <strong>the</strong> fields of atmospheric science, oceanography, geochemistry,<br />

glaciology, underwater filmmaking, and polar exploration—fields<br />

of science crucial to our understanding of Earth’s ecosystems and <strong>the</strong><br />

ongoing causes of global warming. Given <strong>the</strong> importance of <strong>the</strong> subject,<br />

I began to discuss <strong>the</strong> idea of honoring those <strong>explorers</strong> and scientists<br />

on <strong>the</strong> forefront of <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> research at this year’s Lowell Thomas<br />

Awards Dinner with as many members as I could. <strong>The</strong> response I received<br />

was overwhelmingly enthusiastic.<br />

This summer, our members carried <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Flag N o 42 aboard<br />

<strong>the</strong> Russian MIR submersible that became <strong>the</strong> first manned underwater<br />

device to reach “<strong>The</strong> Real North Pole”—landing on <strong>the</strong> seabed some four<br />

kilometers below <strong>the</strong> ice at 90° N. As many of you are aware from <strong>the</strong><br />

press, <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> political debate over this expedition, and because of<br />

<strong>the</strong> political controversy that surrounds this subject as well as our dinner<br />

topic, I think it is important to point out that according to our <strong>Club</strong>’s<br />

bylaws, we take no stand on politics.<br />

As your president, I take pride in celebrating <strong>the</strong> accomplishments of<br />

our fellow members. This new first is an achievement for us as well as<br />

<strong>the</strong> mission of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Club</strong>. Congratulations to Frederik Paulsen, Michael<br />

McDowell, and Anatoly Sagalevitch.<br />

Please accept my personal invitation to enjoy a fabulous and informative<br />

evening on Thursday, October 18th, at Cipriani Wall Street, and<br />

help us honor <strong>the</strong> work of fellow <strong>explorers</strong> Richard Feely, Ph.D., W.<br />

Berry Lyons, Ph.D., Paul A. Mayewski, Ph.D., Julie Palais, Ph.D., Adam<br />

Ravetch, Sarah Robertson, Susan Solomon, Ph.D., and Will Steger.<br />

Invitations are still available online at www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org. Seating is<br />

limited and reservations will be taken on a first-come first-served basis.<br />

Rob Jutson, dinner chair, his entire committee, and I look forward to<br />

seeing you <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

Lowell Thomas Awards Dinner<br />

EXPLORINGCLIMATECHANGE<br />

THE PRESIDENT, DIRECTORS, OFFICERS, OF THE<br />

EXPLORERS CLUB & ROLEX WATCH USA,INC.SALUTE<br />

THE 2007 LOWELL THOMAS AWARD WINNERS.<br />

Richard A. Feely, Ph.D.<br />

W. Berry Lyons, Ph.D. FN’92<br />

Paul A. Mayewski, Ph.D. FN’78<br />

Julie M. Palais, Ph.D. FN’03<br />

Sarah Robertson and Adam Ravetch FN’95<br />

Susan Solomon, Ph.D.<br />

Daniel A. Bennett<br />

Will C. Steger FN’85

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

fall 2007<br />

editor’s note<br />

Something Familiar,<br />

Something Peculiar…<br />

So you have noticed a few <strong>change</strong>s, have you—<strong>the</strong> smaller trim, a higher<br />

page count, <strong>the</strong> perfect bind, and a host of new columns and features?<br />

Driven in large part by a growing concern for <strong>the</strong> environment, we<br />

have redesigned Th e Ex p l o r e r s Jo u r n a l with two goals in mind. Our first<br />

has been to visually capture <strong>the</strong> mystique that is <strong>the</strong> very essence of<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> and literally “put it on paper.” Our second has been<br />

to minimize our ecological footprint by using every square centimeter of<br />

paper on press.<br />

Guiding us in this effort has been Jesse Alexander, a New Yorker with<br />

a passion for exotic travel and a keen eye for all that is cool in <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

Over <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> summer, Jesse and I found ourselves in <strong>the</strong> archives<br />

of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, poring over back <strong>issue</strong>s of Th e Ex p l o r e r s<br />

Jou r n a l since its launch as a pamphlet in 1921. Charting its evolution in<br />

size and use of type, we noted each innovation—<strong>the</strong> first use of images<br />

inside ra<strong>the</strong>r than only on <strong>the</strong> cover, <strong>the</strong> first use of color, and so on—and<br />

marveled at <strong>the</strong> edge of its editorial, particularly during <strong>the</strong> 1950s and<br />

1960s. In recasting Th e Ex p l o r e r s Jo u r n a l , our cues have come from its<br />

past as well as its future.<br />

This <strong>issue</strong> we have brought toge<strong>the</strong>r some of <strong>the</strong> best minds in <strong>climate</strong><br />

research, who are elucidating <strong>the</strong> inner workings of our planet—<br />

separating fact from fiction and human induced <strong>change</strong> from Earth’s<br />

natural process. According to <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Fellow Paul Andrew<br />

Mayewski, who penned <strong>the</strong> lead story in our <strong>climate</strong> package, “more<br />

knowledge is needed, not to demonstrate <strong>the</strong> direction of <strong>change</strong>, but<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r to reduce uncertainty in <strong>the</strong> degree and style of future <strong>change</strong>.”<br />

Having spent <strong>the</strong> better part of four decades on <strong>the</strong> forefront of <strong>climate</strong><br />

research, Mayewski spearheaded <strong>the</strong> Greenland Ice Sheet Project,<br />

which pushed back our knowledge of Earth’s <strong>climate</strong> history by nearly<br />

a million years.<br />

We hope you enjoy our new format and look forward to your feedback!<br />

Angela M.H. Schuster<br />

Acting Editor-in-Chief<br />

image courtesy of © 2007 Will Steger Foundation<br />

salutes <strong>the</strong> 2007 recipients of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> club<br />

Lowell Thomas Award<br />

f o r t h e i r c o n t r i b u t i o n s t o o u r<br />

understanding of Global Climate Change<br />

congratulations to<br />

Richard Feely, Ph.D.<br />

W. Berry Lyons, Ph.D.<br />

Paul Mayewski, Ph.D.<br />

Julie Palais, Ph.D.<br />

Adam Ravetch & Sarah Robertson<br />

Susan Solomon, Ph.D.<br />

Will Steger<br />

Thank you for your efforts to keep our<br />

world in Balance

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

fall 2007<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> club<br />

President<br />

Daniel A. Bennett<br />

Board Of Directors<br />

Officers<br />

PATRONS & SPONSORS<br />

Honorary Chairman<br />

Sir Edmund Hillary,<br />

KG, ONZ, KBE<br />

Honorary President<br />

James M. Fowler<br />

Honor a ry Direc tors<br />

Robert D. Ballard, Ph.D.<br />

George F. Bass, Ph.D<br />

Eugenie Clark, Ph.D.<br />

Sylvia A. Earle, Ph.D.<br />

Col. John H. Glenn Jr., USMC (Ret.)<br />

Gilbert M. Grosvenor<br />

Donald C. Johanson, Ph.D.<br />

Richard E. Leakey, D.Sc.<br />

Roland R. Puton<br />

Johan Reinhard, Ph.D.<br />

George B. Schaller, Ph.D.<br />

Don Walsh, Ph.D.<br />

CLASS OF 2008<br />

Garrett R. Bowden<br />

Jonathan M. Conrad<br />

Kristin Larson, Esq.<br />

Margaret D. Lowman, Ph.D.<br />

Robert H. Whitby<br />

CLASS OF 2009<br />

Daniel A. Bennett<br />

Kenneth M. Kamler, M.D.<br />

Lorie Karnath<br />

<strong>The</strong>odore M. Siouris<br />

Alicia Stevens<br />

CLASS OF 2010<br />

Anne L. Doubilet<br />

William Harte<br />

Kathryn Kiplinger<br />

Daniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.<br />

R. Scott Winters, Ph.D.<br />

Vice President, Chapters<br />

Robert H. Whitby<br />

Vice President, Membership<br />

Lynda Roy<br />

Vice President For Operations<br />

Garrett R. Bowden<br />

Vice President, Research & Education<br />

Margaret D. Lowman, Ph.D.<br />

Treasurer<br />

Mark Kassner<br />

Assistant Treasurer<br />

Kevin O’Brien<br />

Secretary<br />

Daniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.<br />

Assistant Secretary<br />

Anne Doubilet<br />

Patrons Of Exploration<br />

Robert H. Rose<br />

Michael W. Thoresen<br />

Corporate Partner Of Exploration<br />

Rolex Watch U.S.A., Inc.<br />

Corporate Benefactors Of Exploration<br />

Lenovo<br />

Redwood Creek Wines<br />

Corporate Supporter Of Exploration<br />

National Geographic Society<br />

mas<strong>the</strong>ad<br />

EDITORS<br />

Acting Editor-in-Chief<br />

Angela M.H. Schuster<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Jeff Stolzer<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Jeff Blumenfeld<br />

Jim Clash<br />

Clare Flemming, M.S.<br />

Michael J. Manyak , M .D., FAC S<br />

Milbry C. Polk<br />

Carl G. Schuster<br />

Nick Smith<br />

Copy Chief<br />

Valerie Saint-Rossy<br />

ART DEPARTMENT<br />

Art Director<br />

Jesse Alexander<br />

Deus ex Machina<br />

Steve Burnett<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong> © (ISSN 0014-5025) is published<br />

quarterly by <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, 46 East 70th Street, New<br />

York, NY 10021, telephone: 212-628-8383, fax: 212-288-<br />

4449, website: www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org, e-mail: editor@<strong>explorers</strong>.<br />

org. <strong>The</strong> views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily<br />

reflect those of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> or <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong><br />

Journal. Subscriptions should be addressed to: Subscription<br />

Services, Th e Ex p l o r e r s Jo u r n a l , 46 East 70th Street, New<br />

York, NY 10021.<br />

Subscriptions<br />

one year, $29.95; two years, $54.95; three years, $74.95;<br />

single numbers, $8.00; foreign orders, add $8.00 per year.<br />

Members of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> receive Th e Ex p l o r e r s<br />

Jou r n a l as a perquisite of membership.<br />

Postmaster<br />

Send address <strong>change</strong>s to Th e Ex p l o r e r s Jo u r n a l , 46 East<br />

70th Street, New York, NY 10021.<br />

SUBMISSIONS<br />

Manuscripts, books for review, and advertising inquiries<br />

should be sent to <strong>the</strong> Editor, Th e Exp l o r e r s Jo u r n a l , 46 East<br />

70th Street, New York, NY 10021. All manuscripts are subject<br />

to review. Th e Ex p l o r e r s Jo u r n a l is not responsible for<br />

unsolicited materials.<br />

All paper used to manufacture this magazine comes from<br />

well-managed sources. <strong>The</strong> printing of this magazine is FSC<br />

certified and uses vegetable-based inks.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> Journal, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong><br />

<strong>Club</strong> Travelers, World Center for Exploration, and <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Flag and Seal are registered trademarks of<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, Inc., in <strong>the</strong> United States and elsewhere.<br />

All rights reserved. © <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, 2007.<br />

50% RECYCLED PAPER<br />

MADE FROM 15%<br />

POST CONSUMER WASTE

exploration news<br />

edited by Jeff Blumenfeld<br />

Panel Decides<br />

Rules for true circumnavigation<br />

Definitive rules for circumnavigations<br />

of <strong>the</strong> world completed<br />

under human power have been<br />

published by AdventureStats<br />

of <strong>Explorers</strong> Web, Inc., an independent<br />

panel of international<br />

historians, geographers, and<br />

<strong>explorers</strong>. <strong>The</strong>ir conclusions will<br />

ratify existing guidelines held by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Guinness Book of World<br />

Records. <strong>The</strong> rulings will also<br />

clarify <strong>the</strong> recent dispute between<br />

teams from three nations—Britain,<br />

Canada, and Turkey—regarding<br />

<strong>the</strong> first circumnavigation of <strong>the</strong><br />

planet by human power.<br />

Last April a major row erupted<br />

in <strong>the</strong> international press<br />

between Briton Jason Lewis<br />

(above), Canadian Colin Angus,<br />

and Turkish son and long-time<br />

U.S. resident Erden Eruc over<br />

<strong>the</strong> definition of a legitimate human-powered<br />

circumnavigation<br />

(HPC). Angus, who claims to<br />

have completed an HPC in May<br />

2006, traveled exclusively in <strong>the</strong><br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Hemisphere, which,<br />

according to Lewis and Eruc,<br />

does not entitle him to claim a<br />

circumnavigation of <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

world. Guinness also refuted<br />

<strong>the</strong> claim by Angus as <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

criteria for human-powered<br />

circumnavigation feats require<br />

<strong>the</strong> traveler to cross both <strong>the</strong><br />

equator and at least one pair of<br />

antipodal points (locations on<br />

<strong>the</strong> surface of <strong>the</strong> planet that are<br />

diametrically opposite to each<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r). In turn, Angus accused<br />

Guinness of setting <strong>the</strong> rules<br />

on what constitutes a humanpowered<br />

circumnavigation to<br />

suit a Briton—Lewis.<br />

<strong>The</strong> new rules come down<br />

heavily in favor of <strong>the</strong> existing<br />

guidelines set by Guinness,<br />

and for <strong>the</strong> circumnavigation<br />

attempts currently underway by<br />

Lewis and Eruc. <strong>The</strong> panel of experts<br />

recognize Lewis as being<br />

first in line to complete a humanpowered<br />

circumnavigation<br />

when he completes his expedition<br />

October 6 in Greenwich,<br />

England. Lewis’s quest has<br />

been a long-sought grail of circumnavigation<br />

aspirants since<br />

Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition<br />

completed <strong>the</strong> first circumnavigation<br />

of <strong>the</strong> world in 1522.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rules set by<br />

<strong>explorers</strong>web require<br />

<strong>the</strong> circumnavigator to:<br />

• Start and finish at <strong>the</strong> same point,<br />

traveling in one general direction<br />

• Reach two antipodes<br />

• Cross <strong>the</strong> equator<br />

• Cross all longitudes<br />

• Cover a minimum of 40,000 km or<br />

21,600 nautical miles (a great circle)<br />

British yachtsman Adrian<br />

Flanagan, who is sailing <strong>the</strong><br />

first-ever single-handed “vertical”<br />

circumnavigation of <strong>the</strong><br />

globe—considered <strong>the</strong> last great<br />

sailing prize in long-distance,<br />

single-handed sailing—says, “I<br />

agree with all points in <strong>the</strong> defining<br />

criteria, but would expand on<br />

one. In crossing <strong>the</strong> equator, it<br />

needs to be crossed twice in opposite<br />

directions. <strong>The</strong> one really<br />

important point, which <strong>the</strong> panel<br />

does make, is for <strong>the</strong> necessity<br />

of at least one pair of antipodal<br />

points on <strong>the</strong> track. Many sailors<br />

ignore this—all <strong>the</strong> Vendée Globe<br />

racers and <strong>the</strong> Volvo competitors<br />

THE EXPLORERS CLUB TRAVELERS<br />

Please contact us at:<br />

800-856-8951<br />

9am - 6pm Mon-Fri, ET<br />

Toll line: 603-756-4004<br />

Fax: 603-756-2922<br />

Email: ect@studytours.org<br />

Website: www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org<br />

Travel with <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> members<br />

and friends on luxurious adventures far<br />

off <strong>the</strong> beaten path in <strong>the</strong> company of<br />

distinguished & engaging leaders.<br />

FEATURED JOURNEY:<br />

Himalayas by Air<br />

March 21–April 7, 2008(18 days)<br />

A World of Adventures<br />

Experience <strong>the</strong> Himalayas’ diverse ethnic<br />

groups, religious traditions, wildlife habitats,<br />

and biodiversity in a single, unforgettable 18-day<br />

journey, visiting India, Bhutan, Myanmar, and<br />

China, with an extension to Nepal.<br />

SELECTED JOURNEYS<br />

<strong>The</strong> Farside of Antarctica<br />

December 1, 2007–January 7, 2008 (38 days)<br />

Ultimate Serengeti Safari<br />

February 12–24, 2008 (13 days)<br />

Chile’s Patagonian Fjords &<br />

<strong>the</strong> Falkland Islands<br />

February 18–March 2, 2008 (14 days)<br />

From Cape Horn to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cape of Good Hope<br />

February 28–March 22, 2008 (24 days)<br />

8

EXPLORATION NEWS<br />

<strong>The</strong>yLivedAd_FINAL.qxp:Layout 1 6/25/07 4:04 PM Page 1<br />

are thus probably not completing<br />

a ‘true’ circumnavigation.” A<br />

complete set of rules and regulations<br />

for human-powered circumnavigation<br />

are posted at http://<br />

www.adventurestats.com/rules.<br />

shtml#around. For information<br />

on Jason Lewis’s expedition see:<br />

www.expedition360.com.<br />

Happy Birthday Sputnik<br />

Space Race turns 50<br />

October 4 marks <strong>the</strong> fiftieth<br />

anniversary <strong>the</strong> Soviet launch<br />

of Sputnik I, and “<strong>the</strong> singular<br />

event that launched <strong>the</strong> space<br />

age and <strong>the</strong> US–USSR Space<br />

Race,” says NASA web historian<br />

Steve Garber. According to<br />

Garber, <strong>the</strong> world’s first artificial<br />

satellite was about <strong>the</strong> size of<br />

a basketball, weighed only 183<br />

pounds, and took about 98<br />

minutes to orbit <strong>the</strong> Earth on its<br />

elliptical path. “As a technical<br />

achievement, Sputnik caught<br />

<strong>the</strong> world’s attention and <strong>the</strong><br />

American public off guard,”<br />

he says. “More important, <strong>the</strong><br />

launch ushered in new political,<br />

military, technological, and scientific<br />

developments.” For more,<br />

write to histinfo@hq.nasa.gov.<br />

SOUTH POLE THEN<br />

AND NOW<br />

Looking into deep space<br />

It has been 50 years since a team<br />

of 18 men under <strong>the</strong> leadership<br />

of scientist Paul Siple and naval<br />

officer Lt. John Tuck spent <strong>the</strong><br />

first winter/austral summer in<br />

history at <strong>the</strong> South Pole as part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> 1956–57 International<br />

Geophysical Year. <strong>The</strong> “winterovers,”<br />

as <strong>the</strong>y were known,<br />

witnessed sunset and sunrise at<br />

<strong>the</strong> South Pole, events that are<br />

separated in Antarctica by six<br />

months of darkness and almost<br />

unimaginable cold. During that<br />

time, temperatures dropped<br />

to -74.5° Celsius (-102.1°<br />

Fahrenheit) on September 18,<br />

1957, <strong>the</strong> coldest temperature<br />

recorded on Earth at <strong>the</strong> time.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se men laid <strong>the</strong> foundation<br />

for <strong>the</strong> scientific legacy<br />

that continues with <strong>the</strong> recent<br />

inauguration of <strong>the</strong> $19.2-million<br />

South Pole Telescope as part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> International Polar Year<br />

2007–2008. <strong>The</strong> telescope—23<br />

meters high, ten meters across,<br />

and weighing 280 tons—was<br />

test-built in Kilgore, TX, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

taken apart, shipped by boat<br />

to New Zealand, and flown<br />

to <strong>the</strong> South Pole. Since last<br />

November, <strong>the</strong> SPT team under<br />

<strong>the</strong> guidance of project manager<br />

Steve Padin, Senior Scientist in<br />

Astronomy and Astrophysics at<br />

<strong>the</strong> University of Chicago, have<br />

worked to reassemble and deploy<br />

<strong>the</strong> telescope, which is now<br />

up and running. <strong>The</strong> cold, dry<br />

atmosphere above <strong>the</strong> South<br />

Pole will allow <strong>the</strong> SPT to more<br />

easily detect <strong>the</strong> CMB (cosmic<br />

microwave background) radiation,<br />

<strong>the</strong> afterglow of <strong>the</strong> big<br />

bang, with minimal interference<br />

from water vapor. For more on<br />

<strong>the</strong> South Pole Telescope:<br />

http://spt.uchicago.edu/spt.<br />

P e a r y C e n t e n n i a l<br />

Expedition Planned<br />

<strong>The</strong> north beckons Dupre<br />

On February 17, 2009, polar<br />

AVAILABLE NOVEMBER 2007<br />

ISBN: 978-1-59228-991-2<br />

AVAILABLE WHERE BOOKS ARE SOLD<br />

COMINGTO BOOKSTORESTHIS FALL<br />

is <strong>the</strong> latest collection from <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> book series, published<br />

by <strong>The</strong> Lyons Press. Ga<strong>the</strong>red here<br />

are <strong>the</strong> firsthand accounts of more<br />

than forty current members of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Club</strong>, ranging from <strong>the</strong> remarkable to<br />

<strong>the</strong> captivating to <strong>the</strong> bizarre, which<br />

are sure to become a memorable<br />

part of exploration lore for generations<br />

to come.<br />

Included in this exciting collection<br />

are stories such as “A Bad Day at <strong>the</strong><br />

Office” by Robert Ballard, “Flying<br />

Giant of <strong>the</strong> Andes” by Jim Fowler,<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Running of <strong>the</strong> Boundaries” by<br />

Wade Davis, “Race to <strong>the</strong> Moon” by<br />

James Lovell, “Out on a Limb” by<br />

Margaret Lowman, and many more.<br />

This collection redefines what <strong>the</strong><br />

original members called exploration,<br />

reflecting a modern adventurer—<br />

including several women—whose<br />

aim has shifted to protecting national<br />

treasures, preserving <strong>the</strong> planet, and<br />

making discoveries that will benefit<br />

<strong>the</strong> whole of humankind while<br />

expanding <strong>the</strong> world’s knowledge.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Lyons Press is an imprint of<br />

<strong>The</strong> Globe Pequot Press<br />

10

explorer Lonnie Dupre, 46, and<br />

a team of Inuit companions<br />

and <strong>explorers</strong> will begin an<br />

epic dogsled journey through<br />

<strong>the</strong> High Arctic, traveling in <strong>the</strong><br />

footsteps of Robert E. Peary,<br />

who with Mat<strong>the</strong>w A. Henson<br />

and a team of Inuit, became <strong>the</strong><br />

first men to reach <strong>the</strong> North Pole<br />

on April 6, 1909. Although <strong>the</strong><br />

claim was disputed by skeptics,<br />

it was upheld in 1989 by <strong>the</strong><br />

Navigation Foundation (www.<br />

navigationfoundation.org).<br />

According to Dupre, a resident<br />

of Grand Marais, MN, <strong>the</strong><br />

five-month project will begin in<br />

January 2009 with a month and<br />

a half of training dogs, preparing<br />

equipment, and living with<br />

<strong>the</strong> polar Inuit of <strong>the</strong> Qaanaaq<br />

district of northwest Greenland.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n, on February 17, <strong>the</strong> day<br />

<strong>the</strong> sun comes back at <strong>the</strong> end<br />

of four months of polar night,<br />

a team of six <strong>explorers</strong>, three<br />

sleds, and 36 dogs will depart<br />

on <strong>the</strong> 2,400-kilometer journey.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> team is not venturing<br />

to <strong>the</strong> North Pole, <strong>the</strong>y plan to<br />

document all of Peary’s historic<br />

huts, camps, depots, and cairns<br />

in Canada and Greenland.<br />

Dupre will also develop a “Not<br />

Cool” campaign to explain how<br />

<strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> is affecting Inuit<br />

culture and how pollution is<br />

threatening wildlife. For more<br />

information contact: Lonnie<br />

Dupre at lonnie@boreal.org, or<br />

visit www.lonniedupre.com.<br />

How North is North?<br />

12<br />

A once and future land<br />

In July, <strong>the</strong> Euro-American North<br />

Greenland Expedition 2007<br />

flew to <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost coast<br />

of Greenland, <strong>the</strong>n headed<br />

out on <strong>the</strong> sea ice to establish<br />

EXPLORATION NEWS<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re is a more nor<strong>the</strong>rly<br />

point of permanent land<br />

than Kaffeklubben Island, <strong>the</strong><br />

currently established nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

point. Oodaaq Island was<br />

discovered some 1360 meters<br />

north of Kaffeklubben in 1978,<br />

but it has since vanished into<br />

<strong>the</strong> ocean.<br />

Team member Jeff Shea of<br />

Point Richmond, CA, told us,<br />

“We stood on an ‘island’ north<br />

of Kaffeklubben. I put it in quotes<br />

because it appeared to be sitting<br />

on top of <strong>the</strong> sea ice, but we’re<br />

not sure if it was connected to<br />

land. This is representative of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se impermanent features off<br />

<strong>the</strong> north coast of Greenland<br />

near Kaffeklubben. This feature<br />

was shown in a 2005 satellite<br />

image appearing in much <strong>the</strong><br />

same shape as it is in now.<br />

“It looks like an island, but<br />

time will tell if it’s determined<br />

to be <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost,” Shea<br />

says. “For now, we dubbed it<br />

Stray Dog West.”<br />

Nepal seeks peak<br />

fee cut<br />

Everest more economical?<br />

Ang Tshering Sherpa, president<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Nepal Mountaineering<br />

Association, is campaigning to<br />

reduce peak fees in his country<br />

in order to attract more climbers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Nepalese government<br />

has formed a Royalty Revision<br />

Committee, and Ang Tshering’s<br />

hope is that fees will be reduced<br />

across <strong>the</strong> board, according to<br />

<strong>the</strong> American Alpine <strong>Club</strong> News.<br />

In general, Nepal’s peak fees are<br />

higher than those of comparable<br />

mountains in Pakistan, India,<br />

and even China. According to<br />

Reuters, Nepal is already considering<br />

a 50 percent cut in its<br />

peak fees for Everest’s relatively<br />

unpopular fall season.<br />

With <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> decadeold<br />

Maoist insurgency last year,<br />

tourism has rebounded in Nepal<br />

(up 36 percent in <strong>the</strong> first seven<br />

months of 2007 compared to<br />

2006) but it is still far below<br />

historical levels. Ang Tshering<br />

asks that climbers and guides<br />

e-mail <strong>the</strong>ir comments on reducing<br />

peak fees to office@nepal<br />

mountaineering.org and to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ministry of Tourism at<br />

tourism@mail.com.np.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Not So<br />

B l u e D a n u b e<br />

Pollution threatens a European wonder<br />

Eighteen environmental scientists<br />

spent seven weeks traveling<br />

down <strong>the</strong> 2,375-kilometer<br />

Danube to “give <strong>the</strong> river a health<br />

checkup,” according to Philip<br />

Weller, executive secretary of<br />

<strong>the</strong> International Commission<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Protection of <strong>the</strong><br />

Danube River, which organized<br />

<strong>the</strong> study. Known as <strong>the</strong> Joint<br />

Danube Survey 2, <strong>the</strong> trip began<br />

on August 14 in Regensburg,<br />

Germany, and ended in late<br />

September in in Romania and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ukraine. Weller said <strong>the</strong><br />

goal was to ga<strong>the</strong>r information<br />

to improve Danube-related<br />

policies of <strong>the</strong> countries along<br />

<strong>the</strong> river, home to more than 80<br />

million people. For more on this<br />

project, see www.icpdr.org/jds.

P o i n t s<br />

Unknown<br />

into <strong>the</strong> wilds of Patagonia<br />

text by Paul Jeffrey<br />

photographs by Cristian Donoso<br />

Eager to protect <strong>the</strong> dramatic landscapes of western<br />

Patagonia, Cristian Donoso is leading an<br />

expedition by kayak to this region, one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

inhospitable places on earth. Spending five months<br />

navigating open seas and fjords and pulling <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

kayaks across glaciers, Donoso and his team will<br />

face daunting physical and mental challenges as<br />

<strong>the</strong>y ga<strong>the</strong>r information that will inform Chile and<br />

<strong>the</strong> world about this little-known area.<br />

With its labyrinth of rocky islands, serpentine channels<br />

and icy fjords, western Patagonia, in sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Chile, is one of <strong>the</strong> least-explored areas on Earth,<br />

with annual rainfall reaching up to eight meters and<br />

winds frequently rising to hurricane force. Nestled<br />

among glaciers that hug <strong>the</strong> slopes of steep Andean<br />

peaks and drenched by storms that blow out of <strong>the</strong><br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn Pacific, <strong>the</strong> harsh region deters all but <strong>the</strong><br />

hardiest <strong>explorers</strong>.<br />

That has not stopped Cristian Donoso, a young<br />

Chilean lawyer who over <strong>the</strong> past 14 years has<br />

ventured some 40 times into <strong>the</strong> region’s most<br />

inaccessible corners. Just like <strong>the</strong> indigenous<br />

peoples who paddled here in fragile canoes for<br />

thousands of years before <strong>the</strong> arrival of Europeans,<br />

he often travels in a sea kayak, which allows him<br />

to manoeuvre around <strong>the</strong> narrowest fjords and<br />

discover <strong>the</strong>ir hidden beauty.<br />

“In order to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> protection of this<br />

territory, we have got to know what’s <strong>the</strong>re,” says<br />

Donoso, who reports that today most Chileans<br />

have little knowledge of it. He warns that such<br />

ignorance makes it easier for those seeking<br />

commercial gain to exploit <strong>the</strong> region’s natural<br />

resources—seafood, water, virgin forests—with<br />

little respect for its biodiversity.<br />

With his team of three men and one woman,<br />

<strong>the</strong> 31-year-old explorer has embarked on an<br />

ambitious five-month Transpatagonia Expedition<br />

that started this September. <strong>The</strong>y will traverse<br />

2,039 kilometers of <strong>the</strong> central part of western<br />

Patagonia on open sea, lakes, and rivers, as well<br />

as travelling overland for about 150 kilometers,<br />

dragging kayaks with provisions—weighing some<br />

100 kilograms each—behind <strong>the</strong>m as sledges.<br />

<strong>The</strong> group will ascend unclimbed peaks and visit<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

uncharted territories.<br />

To enhance understanding of <strong>the</strong> region’s<br />

geological past, soil and rock samples will<br />

be collected and analyzed by scientists.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> will also collect geological<br />

evidence, including stalagmites in caves<br />

on Madre de Dios Island, showing how <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>climate</strong> has <strong>change</strong>d over time.<br />

Scholars of <strong>the</strong> region’s human history<br />

eagerly await <strong>the</strong> expedition’s reports on<br />

<strong>the</strong> remains of fishing and hunting camps<br />

that belonged to <strong>the</strong> Kaweskars, who lived<br />

in <strong>the</strong> region for more than 4,000 years.<br />

A famous incident, <strong>the</strong> 1741 sinking<br />

of <strong>the</strong> English frigate Wager on <strong>the</strong> north<br />

coast of <strong>the</strong> Guayaneco Archipelago, will<br />

come alive again when expedition divers<br />

search for <strong>the</strong> wreck’s exact location. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

will <strong>the</strong>n trace <strong>the</strong> route described in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>journal</strong> of John Byron, who survived <strong>the</strong><br />

shipwreck thanks to assistance from two<br />

indigenous groups, who spirited him and<br />

three o<strong>the</strong>r survivors through <strong>the</strong> treacherous<br />

waters in <strong>the</strong>ir canoes.<br />

Donoso, a 2006 Rolex Enterprise Awards Laureate,<br />

is planning to produce a documentary video for<br />

broadcast on Chilean television in 2008. To follow<br />

his expedition, September through January, see his<br />

website at: http://patagoniaincognita.blogspot.com.<br />

biography<br />

Paul Jeffrey is an Oregon-based writer and photographer<br />

who has covered international emergencies<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> genocide in Darfur, Sudan, and <strong>the</strong> tsunami<br />

in South Asia.<br />

14 <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

A M o u n ta i n<br />

of <strong>The</strong>ir Own<br />

after leading dozens of clients up<br />

<strong>the</strong> world’s highest peak, two of<br />

Everest’s best climb for <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

text by Brett Prettyman<br />

From his first glimpse of <strong>the</strong> tiny man with <strong>the</strong> effervescent<br />

smile, Geoff Tabin knew Apa Sherpa was<br />

different. It was 1988, and Tabin was serving as <strong>the</strong><br />

doctor on an expedition on Mount Everest that had<br />

hired Apa as part of <strong>the</strong> climbing support team.<br />

“He was very shy, very cheerful, and unbelievably<br />

strong,” Tabin said. “He had<br />

this incredible balance about<br />

him. While o<strong>the</strong>r Sherpas<br />

carrying <strong>the</strong> same<br />

loads were plodding<br />

along he<br />

was skipping<br />

and dancing up <strong>the</strong> mountain. And that smile…he<br />

just never quit smiling.”<br />

While Apa didn’t make it to <strong>the</strong> top of<br />

Chomolungma in 1988—Tabin did—<strong>the</strong> Sherpa<br />

man from Thame managed to string toge<strong>the</strong>r an<br />

unbelievable list of summits in <strong>the</strong> ensuing years.<br />

Today, 19 years later, <strong>the</strong> 5-foot-4 and 120-pound<br />

Apa is still displaying what has become <strong>the</strong> trademark<br />

grin of <strong>the</strong> man who has skipped to <strong>the</strong> summit<br />

of Everest more than any o<strong>the</strong>r human, most<br />

recently on May 16, 2007. This past spring, <strong>the</strong><br />

reserved yet still distinctly feisty 47-year-old broke<br />

his own world record with a seventeenth trip to<br />

<strong>the</strong> highest point on <strong>the</strong> planet—four of which<br />

were made without oxygen. Apa made his first<br />

16 Everest summits while employed by clients<br />

to get <strong>the</strong>m to 29,035 feet above sea level. This<br />

time <strong>the</strong>re were no clients, just family, friends, and<br />

fellow Everest record setter Lhakpa Gelu Sherpa,<br />

who in 2003 set a speed record for <strong>the</strong> fastest<br />

summit from basecamp in just under 11 hours.<br />

Apa and Lhakpa surrounded <strong>the</strong>mselves with<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r Sherpas, many of <strong>the</strong>m extended family and<br />

friends, to round out <strong>the</strong> climbing members of <strong>the</strong><br />

SuperSherpas Expedition.<br />

“All <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r times I was <strong>the</strong>re for a job to<br />

16 <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

get o<strong>the</strong>rs to <strong>the</strong> top to try and support my family.<br />

This time Lhakpa and I did it not only for our<br />

families but for all <strong>the</strong> Nepali people,” Apa said<br />

from his current home in Salt Lake City, UT, where<br />

Lhakpa also lives. “I am very proud of our team,<br />

<strong>the</strong> history we made, and <strong>the</strong> awareness we have<br />

brought to <strong>the</strong> Sherpa people.”<br />

Free of <strong>the</strong> constraints and obligations to get<br />

clients to <strong>the</strong> top, <strong>the</strong> SuperSherpas basically<br />

raced from Camp 2 to <strong>the</strong> summit, passing o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

climbers hunkered down in tents trying to acclimatize<br />

to <strong>the</strong> elevation. <strong>The</strong> SuperSherpas team<br />

started its final push for <strong>the</strong> summit on May 14,<br />

spending <strong>the</strong> night at Camp 2 (21,300 feet), and<br />

<strong>the</strong>n climbed to Camp 4—a gain of more than<br />

4,200 feet—in nine hours. After a four-hour rest at<br />

Camp 4, <strong>the</strong>y took off at 10 P.M. and summitted<br />

at approximately 8:45 A.M. on May 16. <strong>The</strong> team<br />

climbed more than 7,700 vertical feet in less than<br />

24 hours—and at <strong>the</strong> highest altitude in <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

“This trip was not as hard as o<strong>the</strong>rs when we<br />

had to help o<strong>the</strong>rs so much,” Lhakpa said. “Our<br />

Sherpa team was so strong and we didn’t have<br />

to turn around for anything. I am so very proud of<br />

how we worked as a team.”<br />

“If <strong>the</strong>re is anything good that comes from our<br />

summit…our goal would be to create a more<br />

peaceful world,” Apa and Lhakpa radioed <strong>the</strong><br />

SuperSherpas basecamp shortly after reaching<br />

<strong>the</strong> summit. “Our second goal would be to<br />

continue in Sir Edmund Hillary’s footsteps and<br />

contribute to education and improving health care<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Khumbu region, and for all Nepali people<br />

in <strong>the</strong> remote regions.” To raise awareness of <strong>the</strong><br />

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF SUPERSHERPAS LLC<br />

role of Sherpas and <strong>the</strong> need for a better education<br />

system in <strong>the</strong>ir home country, a documentary<br />

is being made about <strong>the</strong> expedition—filmed entirely<br />

by Sherpas, of course.<br />

Apa and Lhakpa never made it out of grade<br />

school in Nepal. <strong>The</strong>y both became porters for<br />

Everest expeditions at an early age to support<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir families. <strong>The</strong> men eventually proved <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

worthy of becoming part of climbing teams<br />

and started leading people to <strong>the</strong> top. Even as<br />

<strong>the</strong> most accomplished climber on Everest, Apa<br />

still made less than 20 percent of <strong>the</strong> money<br />

Western guides pull in for taking clients to <strong>the</strong> top.<br />

Because <strong>the</strong>y spend more time on <strong>the</strong> mountain<br />

helping prepare camps for <strong>the</strong> climbers, Sherpas<br />

are also exposed to <strong>the</strong> dangers of Everest more<br />

frequently than Western climbers.<br />

Apa and Lhakpa decided it was time to draw<br />

attention to <strong>the</strong> Sherpa people and <strong>the</strong> fact that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have been involved in some way on every<br />

expedition attempt since people started trying to<br />

conquer Everest in <strong>the</strong> 1920s. <strong>The</strong> men are also<br />

hoping that <strong>the</strong>ir success will help raise money for<br />

more and better education for all Nepali children,<br />

and create a better pay scale for Sherpas involved<br />

in expeditions.<br />

Because <strong>the</strong>y live at high elevations <strong>the</strong>ir entire<br />

lives, Sherpas do not need to go through <strong>the</strong><br />

lengthy process of acclimating <strong>the</strong>ir bodies to <strong>the</strong><br />

grueling demands of extreme heights. Amazingly,<br />

research on <strong>the</strong> Sherpas’ ability to cope with high<br />

elevations has not been done. Researchers from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Orthopedic Specialty Hospital in Utah asked<br />

Apa and Lhakpa to undergo a barrage of tests<br />

before leaving Salt Lake City for Kathmandu, and<br />

again during <strong>the</strong> climb. Results from <strong>the</strong> medical<br />

and nutritional research are still being analyzed,<br />

but it is clear that <strong>the</strong>re is something unique about<br />

<strong>the</strong> Sherpas that allows <strong>the</strong>m to excel at elevation<br />

where o<strong>the</strong>rs break down.<br />

Making it to <strong>the</strong> top is always a thrilling, but all<br />

climbers know an expedition is only a success if<br />

<strong>the</strong>y make it back home. Apa and Lhakpa were<br />

almost back to basecamp, about halfway through<br />

<strong>the</strong> Khumbu Icefall, when <strong>the</strong>y were asked to head<br />

back up <strong>the</strong> mountain to help retrieve <strong>the</strong> body of<br />

a climber who had been killed in an avalanche.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>y had never met <strong>the</strong> Korean man who<br />

perished, Apa and Lhakpa honored his family by<br />

helping to bring his body back down <strong>the</strong> mountain.<br />

This required going through <strong>the</strong> icefall at <strong>the</strong><br />

time of highest risk, late in <strong>the</strong> day after warming<br />

from <strong>the</strong> intense sun. Many climbers, including<br />

Apa, believe <strong>the</strong> icefall is <strong>the</strong> most dangerous part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Everest climb.<br />

<strong>The</strong> record-holders finally made it back to<br />

basecamp, albeit on a sad note, but <strong>the</strong>y still<br />

found energy enough to celebrate with <strong>the</strong> basecamp<br />

team. <strong>The</strong>y started by calling <strong>the</strong>ir families.<br />

Missing his wife and three children in Utah, Apa<br />

was in a hurry to get back to <strong>the</strong> United States,<br />

so <strong>the</strong> team wasted little time packing up camp.<br />

“We were <strong>the</strong> last to arrive and <strong>the</strong> first to leave,”<br />

Lhakpa said about <strong>the</strong> mere 22-days <strong>the</strong> team<br />

spent at basecamp, surely ano<strong>the</strong>r record for<br />

Everest expeditions. “Everybody was jealous that<br />

we had managed to make <strong>the</strong> climb so quick.”<br />

Lhakpa was also excited to get home, but he<br />

had a present to pick up for his wife Fuli. <strong>The</strong> team<br />

headed to Kathmandu, where <strong>the</strong>y were treated<br />

like royalty and swarmed by <strong>the</strong> media and wellwishers.<br />

When things finally settled down for<br />

<strong>the</strong> heroes, <strong>the</strong>y headed for <strong>the</strong> U.S. Embassy in<br />

Kathmandu, hoping to get final permission to take<br />

Lhakpa’s three children—ages 10 to 16—to North<br />

America. It took some work, but permission was<br />

granted and <strong>the</strong> team plus three returned to Utah<br />

on May 30. “I feel like we have accomplished so<br />

many goals, but it is most important that <strong>the</strong> children<br />

are here now with <strong>the</strong>ir mo<strong>the</strong>r,” said Lhakpa.<br />

“Education is so important and now <strong>the</strong>y can go to<br />

schools here and be with us.”<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>y both hint that <strong>the</strong>ir time on<br />

Everest is over, Apa and Lhakpa both say it is<br />

too soon after <strong>the</strong>ir latest expedition to decide<br />

if <strong>the</strong>y will return to attempt ano<strong>the</strong>r climb. “One<br />

never knows. We will have to see what happens<br />

in <strong>the</strong> future. <strong>The</strong> mountain will always be <strong>the</strong>re,”<br />

<strong>the</strong>y said.<br />

information<br />

For more information on <strong>the</strong> SuperSherpas Expedition visit<br />

www.supersherpas.com. For a detailed day-by-day account<br />

of <strong>the</strong> expedition with pictures, video, and notes from Mount<br />

Everest basecamp visit: www.sherpas.sltrib.com.<br />

biography<br />

Brett Prettyman has been an outdoors writer and editor for<br />

<strong>The</strong> Salt Lake Tribune since 1990.<br />

18 <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

exploring <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong><br />

charting a new course<br />

for<br />

Plan e t<br />

Earth<br />

by margaret D. Lowman<br />

<strong>The</strong> Dry Valleys in Antarctica, photo by David Marchant, Boston University<br />

“A race is now on between <strong>the</strong> techno-scientific<br />

forces that are destroying <strong>the</strong> living environment<br />

and those that can be harnessed to save it.”<br />

- E.O. Wilson<br />

For more than a century, <strong>the</strong> collective talents<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> have tested <strong>the</strong> limits of<br />

human stamina. Our members have rocketed<br />

into space, dived deep into our oceans, and<br />

ventured into cave systems and rainforest canopies.<br />

And, in <strong>the</strong> process of exploring our planet,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have been instrumental in pioneering new<br />

technologies to facilitate <strong>the</strong> discovery and<br />

recovery of information, whe<strong>the</strong>r a new species<br />

or previously unknown geophysical process.<br />

Perhaps more important, our colleagues have<br />

championed <strong>the</strong> need to conserve Earth’s wild<br />

places not only for <strong>explorers</strong> of <strong>the</strong> future but<br />

for humanity as a whole.<br />

In his new book, <strong>The</strong> Revenge of Gaia, British<br />

environmental writer James Lovelock, who has<br />

long viewed our planet as a complex superorganism,<br />

claims that Earth is about to catch a<br />

morbid fever that may last as long as 100,000<br />

years. Climate <strong>change</strong> is not a localized phenomenon—restricted<br />

to developing countries or<br />

expanding urban areas. It is a global <strong>issue</strong> that<br />

affects <strong>the</strong> entire planet. Hurricanes are increasing<br />

in numbers and intensity as a consequence<br />

of <strong>the</strong> warmer oceans that trigger increased<br />

storm cycles. Warmer temperatures are melting<br />

polar ice at unprecedented rates, and also drying<br />

out remaining fragments of tropical rainforest,<br />

leading to increased fire frequency. Most<br />

scientists, myself included, agree that Earth<br />

is rapidly approaching a tipping point, beyond<br />

which <strong>the</strong> costs and technology for ecosystem<br />

repair may become prohibitive.<br />

For <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, what began as an<br />

idea embraced by a select few of our members<br />

has become a mandate for our organization—to<br />

ensure a healthy future for global exploration.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> club’s vice president for research and<br />

education, I will be working with our president,<br />

Daniel A. Bennett, and our board of directors<br />

to guarantee that research and education become<br />

primary components of all expeditions<br />

supported by <strong>the</strong> organization.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> future may look bleak for <strong>the</strong> environment,<br />

we believe our profound desire to chart<br />

a new course for our planet offers exciting economic<br />

opportunities for new green technologies<br />

and initiatives. As <strong>explorers</strong>, our goal is not only<br />

to explore, but to educate and inspire.<br />

20 <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

exploring <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> No. 1<br />

Venturing<br />

Of <strong>the</strong><br />

to <strong>the</strong> Ends<br />

Earth<br />

exploring our planet’s polar regions:<br />

chroniclers of <strong>the</strong> past and portents of <strong>the</strong> future<br />

by Paul Andrew Mayewski<br />

It has been 50 years since <strong>the</strong> first International<br />

Geophysical Year (IGY) invited <strong>the</strong> best minds in<br />

science from around <strong>the</strong> globe to join forces in tackling<br />

<strong>issue</strong>s such as understanding Earth’s oceans<br />

and atmosphere and <strong>the</strong> delicate relationship<br />

between <strong>the</strong>m. Since <strong>the</strong>n, many advances have<br />

been made in this area, among <strong>the</strong> most important,<br />

<strong>the</strong> understanding of <strong>the</strong> role of greenhouse<br />

gases such as carbon dioxide (CO 2<br />

) in determining<br />

Earth’s <strong>climate</strong>. In more recent years, a realization<br />

that gases such as CO 2<br />

are on <strong>the</strong> rise has led to an<br />

interest in determining and documenting past levels<br />

of greenhouse gases. Ga<strong>the</strong>ring such information,<br />

however, entails journeying literally to <strong>the</strong> ends of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Earth. For <strong>the</strong>re, locked in thousands of meters<br />

of ice, are records of our planet’s changing chemical<br />

and physical <strong>climate</strong> that stretch back nearly a<br />

million years.<br />

When I began my <strong>climate</strong> research nearly 40<br />

years ago, few in <strong>the</strong> scientific community regarded<br />

Earth’s polar regions as important to <strong>the</strong><br />

vast majority of civilization. At that time, Antarctica<br />

was viewed as not only a frozen continent but also<br />

a continent frozen in time. This view seemed to<br />

be amply supported by <strong>the</strong> ice-free valleys of <strong>the</strong><br />

Victoria Land Coast in East Antarctica, where<br />

rocks had been exposed to millions of years of<br />

wind erosion, creating timeless landscapes. <strong>The</strong><br />

vast interior of <strong>the</strong> polar plateau also appeared to<br />

be <strong>change</strong>less to <strong>the</strong> few limited expeditions that<br />

passed but once across <strong>the</strong> surface.<br />

Increased access to <strong>the</strong> most remote portions<br />

of Antarctica and <strong>the</strong> Arctic—afforded by aircraft<br />

and ship in recent years—complemented by our<br />

ability to mount lighter, faster, and more efficient<br />

expeditions and establish well-equipped field stations,<br />

has resulted in <strong>the</strong> acquisition of an abundance<br />

of information that is dramatically changing<br />

our understanding of <strong>the</strong> critical role polar regions<br />

play in Earth’s complex ecosystem.<br />

Remarkably, <strong>the</strong>se regions have now emerged<br />

as “first responders” for monitoring current <strong>climate</strong><br />

because <strong>the</strong>y are so sensitive to warming;<br />

<strong>the</strong> vast ice-trapped environmental libraries <strong>the</strong>y<br />

host chronicle hundreds of thousands of years of<br />

Earth’s <strong>climate</strong> history. <strong>The</strong> ice cores we extract<br />

from <strong>the</strong> polar regions contain highly robust records<br />

of past <strong>climate</strong>. <strong>The</strong>se ancient records not<br />

only allow us to better understand <strong>the</strong> long-term<br />

cyclical <strong>change</strong>s in <strong>climate</strong> caused by natural phenomena<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> 26,000-year precession of<br />

<strong>the</strong> equinoxes, which is in part responsible for <strong>the</strong><br />

ice ages; volcanic eruptions; and solar activity, but<br />

to separate <strong>the</strong>se factors from variations in <strong>climate</strong><br />

22 <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

Discovery of abrupt <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> by <strong>the</strong> Greenland<br />

Ice Sheet Project Two (GISP2) in 1992 revolutionized<br />

<strong>the</strong> understanding of <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong>.<br />

Prior to 1992 <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> was viewed as a slow<br />

process, taking thousands of years. Following<br />

1992 <strong>change</strong>s in temperature and atmospheric<br />

circulation intensity were demonstrated to operate<br />

frequently and rapidly (<strong>change</strong> in less than 10<br />

and in some cases less than two years). Data for<br />

this figure from: Mayewski et al., 1994, Science,<br />

1997, Journal of Geophysics; Grootes et al., 1997,<br />

Journal of Geophysics.<br />

wrought by human activity. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> study of<br />

particularly deep ice cores such as those we have<br />

recovered from Greenland and Antarctica is yielding<br />

a number of paradigm-changing concepts<br />

about how <strong>the</strong> <strong>climate</strong> system operates.<br />

When I directed <strong>the</strong> Greenland Ice Sheet<br />

Project 2 (GISP2) in 1993, we recovered <strong>the</strong> first<br />

ice core to bedrock, extending to 3,056 meters,<br />

below <strong>the</strong> surface in Greenland. <strong>The</strong> resulting <strong>climate</strong><br />

record was annually dated back to 110,000<br />

years ago and instead of demonstrating, as<br />

assumed to that date, that <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong>s slowly<br />

over hundreds to thousands of years, showing<br />

that temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric<br />

circulation can <strong>change</strong> dramatically in <strong>the</strong> span of<br />

a decade. <strong>The</strong> finding was an absolute break with<br />

scientific consensus.<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea that in less than a decade—and in some<br />

cases within two years—<strong>the</strong> <strong>climate</strong> in a region<br />

could <strong>change</strong> so rapidly opened up <strong>the</strong> possibility<br />

for significant <strong>climate</strong> surprises. Close correlation<br />

between <strong>the</strong> abrupt <strong>climate</strong> events evident in ice<br />

core records and those found in cores taken from<br />

ocean floor sediments suggested that <strong>change</strong>s<br />

in ocean circulation accompany <strong>change</strong>s in <strong>the</strong><br />

atmosphere.<br />

Such abrupt <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> events appear to<br />

be most dramatic in <strong>the</strong> North Atlantic, no doubt a<br />

consequence of <strong>the</strong> fortuitous shape of <strong>the</strong> North<br />

Atlantic basin with respect to sea ice formation,<br />

which allows <strong>the</strong> extent of sea ice to vary over<br />

a considerable area. Examination of <strong>the</strong> GISP2<br />

ice cores reveal that since <strong>the</strong> departure of <strong>the</strong><br />

major Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Hemisphere ice sheets some<br />

10,000 years ago, abrupt <strong>climate</strong> events are of<br />

significantly smaller magnitude—a mere 1º to 2ºC<br />

in temperature—than <strong>the</strong>ir Ice Age counterparts.<br />

Yet such seemingly small <strong>change</strong>s in <strong>climate</strong> can<br />

have a major impact on ecosystems and civilizations.<br />

<strong>The</strong> demise of <strong>the</strong> Akkadian culture in Mesopotamia<br />

4,200 years ago and <strong>the</strong> decline of <strong>the</strong> Maya civilization<br />

ca. A.D. 900 can both be attributed in large<br />

part to shifts in atmospheric circulation, which led to<br />

drought. <strong>The</strong> Norse colonies in Greenland in A.D.<br />

1400 found <strong>the</strong>mselves more isolated with each<br />

passing year as a consequence of increased sea<br />

ice, which made it impossible for European ships<br />

to resupply <strong>the</strong> settlements. <strong>The</strong>se findings send a<br />

clear and imperative message to modern society: we<br />

are not immune to even small <strong>change</strong>s in <strong>climate</strong>.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> Arctic Climate Impact Assessment<br />

(AICA)—which included not only our ice core data,<br />

but research from many o<strong>the</strong>r Arctic projects—was<br />

released in 2004, it demonstrated without a doubt<br />

that our planet was well into <strong>the</strong> initial stages of<br />

warming and, as expected, early evidence would<br />

come from <strong>the</strong> polar regions, notably temperaturesensitive<br />

Arctic sea ice and surrounding glaciers.<br />

Earth’s nor<strong>the</strong>rn polar reaches consist of a vast<br />

ocean encircled by land—<strong>the</strong> inverse of <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

polar region. Arctic seas and lands are home<br />

to diverse populations of wildlife, vegetation, and<br />

people. In recent decades, <strong>the</strong> delicate Arctic <strong>climate</strong><br />

balance has begun to <strong>change</strong> dramatically<br />

as a consequence of greenhouse gas warming.<br />

<strong>The</strong> extent and thickness of sea ice has diminished,<br />

permafrost is thawing, coastal erosion is<br />

accelerating, <strong>the</strong> abundance and distribution of<br />

plants and animals has been altered, and glaciers<br />

are retreating at accelerating rates.<br />

A soon-to-be-released study developed by<br />

several of us under <strong>the</strong> auspices of <strong>the</strong> Scientific<br />

Committee for Antarctic Research (SCAR), entitled<br />

<strong>the</strong> State of <strong>the</strong> Antarctic and <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Ocean Climate System, emphasizes <strong>the</strong> critical<br />

role that region plays in <strong>the</strong> global <strong>climate</strong> system.<br />

Climate over <strong>the</strong> Antarctic is profoundly influenced<br />

by its massive ice sheet, which in places is more<br />

than 4,000 meters thick. Antarctica holds some 80<br />

percent of <strong>the</strong> world’s fresh water as ice (glaciers<br />

outside Antarctica comprise ano<strong>the</strong>r ten percent)<br />

and along with its surrounding sea ice, <strong>the</strong> resulting<br />

whiteness plays a major role in Earth’s ability to reflect<br />

incoming solar radiation. <strong>The</strong> white reflective<br />

surface of <strong>the</strong> Antarctic ice sheet is doubled in size<br />

during <strong>the</strong> maximum yearly extent of sea ice and<br />

sea ice is highly sensitive to <strong>change</strong>s in ocean and<br />

surface air temperatures, making it a highly dynamic<br />

component of <strong>the</strong> global <strong>climate</strong> system. <strong>The</strong> extent<br />

of <strong>the</strong> sea ice and its duration determines <strong>the</strong> vigor<br />

of heat ex<strong>change</strong> between <strong>the</strong> ocean and overlying<br />

atmosphere.<br />

Surface and subsurface melting of Antarctic ice<br />

into <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ocean leads to <strong>the</strong> production<br />

of <strong>the</strong> coldest, densest water on <strong>the</strong> planet. <strong>The</strong><br />

strongest winds on Earth encircle <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

and blow over <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ocean. <strong>The</strong> combination<br />

of winds and dense bottom water production<br />

are primary drivers of <strong>the</strong> world’s largest ocean<br />

current system and <strong>the</strong>refore are of critical importance<br />

to <strong>the</strong> transport of heat and moisture<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> planet.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Antarctic ice sheet is today one-and-a-half<br />

times <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> United States and has a<br />

sea level equivalent, if completely melted, of 57<br />

meters. By virtue of its size, reflectivity, and its<br />

surrounding ocean that acts as a heat sink, <strong>the</strong><br />

warming impact of human source <strong>change</strong>s in<br />

greenhouse gases (rise in CO 2<br />

, CH 4<br />

, and N 2<br />

O,<br />

and decrease in upper atmosphere O 3<br />

) may be<br />

partially buffered, but for how long? Mounting<br />

evidence suggests that warming is beginning to<br />

impact ever-increasing portions of <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

and Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ocean. Model projections suggest<br />

that over <strong>the</strong> twenty-first century <strong>the</strong> Antarctic interior<br />

will warm by approximately 3º to 4ºC, which<br />

exceeds temperatures of <strong>the</strong> last few million years<br />

for this region, and sea ice extent will decrease by<br />

some 30 percent. Estimates for sea level rise are<br />

on <strong>the</strong> order of six to seven meters over <strong>the</strong> next<br />

2,000 years, but <strong>the</strong>re is no reason to assume that<br />

<strong>the</strong> rate of <strong>change</strong> will be linear. Massive melting<br />

and sea level rise could occur at any time as a<br />

consequence of ice sheet destabilization (through<br />

heating of surface ice, basal ice, or ocean-ice<br />

contact points). Changes in <strong>climate</strong> (temperature,<br />

precipitation, ocean and atmospheric circulation,<br />

sea ice, atmospheric chemistry) over <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ocean will have a dramatic impact<br />

on <strong>the</strong> global <strong>climate</strong> system.<br />

Significant regional <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong>s have<br />

already taken place in <strong>the</strong> Antarctic during <strong>the</strong><br />

past 50 years. Atmospheric temperatures have<br />

increased markedly over <strong>the</strong> Antarctic Peninsula.<br />

Glaciers are retreating on <strong>the</strong> Antarctic Peninsula,<br />

in Patagonia (see page 36), on <strong>the</strong> sub-Antarctic<br />

islands, and in West Antarctica adjacent to <strong>the</strong><br />

peninsula. <strong>The</strong> penetration of marine air masses<br />

has become more pronounced over portions<br />

of West Antarctica. Well above <strong>the</strong> surface,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Antarctic atmosphere has warmed during<br />

winter. <strong>The</strong> upper kilometer of <strong>the</strong> circumpolar<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ocean has warmed, Antarctic bottom<br />

water across a wide sector of east Antarctica<br />

has freshened, and <strong>the</strong> densest bottom water in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Weddell Sea has also warmed. In contrast<br />

to <strong>the</strong>se regional <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong>s, over most of<br />

Antarctica near-surface temperature and snowfall<br />

have not increased significantly during at least<br />

<strong>the</strong> past 50 years (<strong>the</strong>refore no offset thus far for<br />

rising sea level due to melting), and ice-core data<br />

suggest that <strong>the</strong> atmospheric circulation over <strong>the</strong><br />

interior has thus far remained in a similar state for<br />

at least <strong>the</strong> past 200 years.<br />

Due to its unique meteorological and photochemical<br />

environment, <strong>the</strong> atmosphere over<br />

Antarctica has experienced <strong>the</strong> most significant<br />

depletion of stratospheric O 3<br />

on <strong>the</strong> planet, detected<br />

through monitoring that began with <strong>the</strong> IGY<br />

five decades ago. <strong>The</strong> depletion is in response<br />

to <strong>the</strong> stratospheric accumulation of man-made<br />

chemicals produced largely in <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Hemisphere. <strong>The</strong> ozone hole influences <strong>the</strong> <strong>climate</strong><br />

of Antarctica (smaller ozone holes also impact <strong>the</strong><br />

24 <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

sou<strong>the</strong>rn victoria land<br />

antartica<br />

Mt. Erebus, <strong>the</strong> only active volcano exposed on <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

continent; <strong>the</strong> massive Ross Ice Shelf, which drains glaciers<br />

flowing out of <strong>the</strong> Transantarctic Mountains and portions of<br />

West Antarctica; and <strong>the</strong> city block-size icebergs spawned off<br />

<strong>the</strong> ice shelf can be seen from <strong>the</strong> coast of Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Victoria<br />

Land, East Antarctica.<br />

Arctic), allowing solar radiation to penetrate to <strong>the</strong><br />

surface, and along with <strong>the</strong> global rise in CO 2<br />

,<br />

CH 4<br />

, and N 2<br />

O, provides immense potential for <strong>climate</strong><br />

<strong>change</strong> over <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Hemisphere. <strong>The</strong><br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ocean is our most biologically productive<br />

ocean and a significant sink for both heat and<br />

CO 2<br />

, making it critical to <strong>the</strong> evolution of <strong>climate</strong><br />

past and present. <strong>The</strong>refore it acts as a wild card<br />

for future <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> that is human-induced.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Arctic Ocean is expected to be nearly ice<br />

free by <strong>the</strong> latter twenty-first century in response to<br />

greenhouse gas warming. In <strong>the</strong> process, habitats<br />

and lifestyles throughout <strong>the</strong> Arctic will continue to<br />

<strong>change</strong> dramatically. A <strong>climate</strong> surprise portented<br />

by our ice core research in Greenland may appear<br />

in <strong>the</strong> cooling of nor<strong>the</strong>rn Europe, induced through<br />

warming, which increases Arctic ice melt. This in<br />

turn increases <strong>the</strong> influx of fresh water into <strong>the</strong> North<br />

Atlantic. <strong>The</strong> salinity decrease as a consequence<br />

of <strong>the</strong> freshening in <strong>the</strong> Arctic may be sufficient to<br />

reduce <strong>the</strong> density of North Atlantic surface water,<br />

leading to a reduction in deepwater production and,<br />

as a consequence, reduced heat transport to nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Europe. In addition, <strong>change</strong>s in precipitation<br />

and atmospheric circulation are evolving over <strong>the</strong><br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Hemisphere as a result of warming over<br />

<strong>the</strong> Arctic and lower latitudes.<br />

Temperatures of <strong>the</strong> last few decades are <strong>the</strong><br />

highest recorded in <strong>the</strong> instrumental era—<strong>the</strong><br />

last 100 years—and through examination of temperature<br />

reconstructions utilizing ice core, tree<br />

ring, historical, and o<strong>the</strong>r data series, it is clear<br />

that Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Hemisphere temperatures are <strong>the</strong><br />

highest of at least <strong>the</strong> last millennium. This finding,<br />

repeated by several investigators and validated by<br />

numerous reviews of <strong>the</strong> data, is a consequence<br />

26 <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

nor<strong>the</strong>rn victoria land<br />

antartica<br />

During our first over-snow exploration of a vast region of<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Victoria Land in 1974-75, our four-member University<br />

of Maine team spent more than 100 days traversing<br />

<strong>the</strong> mountains and crevasse fields of this remote region of<br />

Antarctica<br />

of human activities that have led to rapid recent<br />

rise in greenhouse gases. <strong>The</strong> effects of this rise<br />

will be part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> system for many<br />

decades to come.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is, however, even more to <strong>the</strong> story of human<br />

impact on <strong>the</strong> chemistry of <strong>the</strong> atmosphere<br />