JOURNAL - International Childbirth Education Association

JOURNAL - International Childbirth Education Association

JOURNAL - International Childbirth Education Association

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

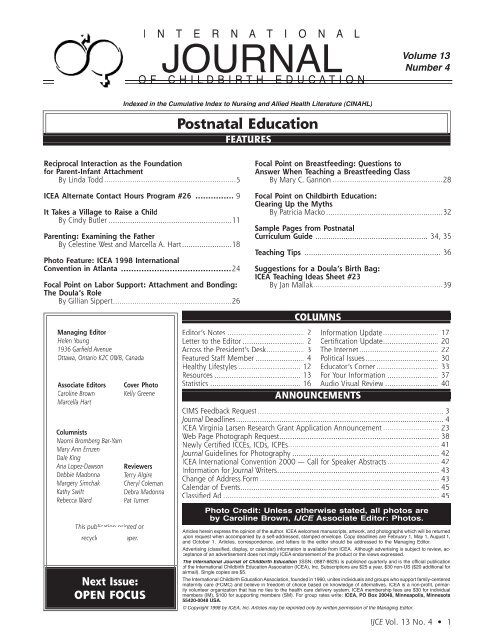

I N T E R N A T I O N A L<br />

<strong>JOURNAL</strong><br />

O F C H I L D B I R T H E D U C A T I O N<br />

Volume 13<br />

Number 4<br />

Indexed in the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)<br />

Postnatal <strong>Education</strong><br />

FEATURES<br />

Reciprocal Interaction as the Foundation<br />

for Parent-Infant Attachment<br />

By Linda Todd .............................................................5<br />

Focal Point on Breastfeeding: Questions to<br />

Answer When Teaching a Breastfeeding Class<br />

By Mary C. Gannon ...................................................28<br />

ICEA Alternate Contact Hours Program #26 ............... 9<br />

It Takes a Village to Raise a Child<br />

By Cindy Butler .........................................................11<br />

Parenting: Examining the Father<br />

By Celestine West and Marcella A. Hart .......................18<br />

Photo Feature: ICEA 1998 <strong>International</strong><br />

Convention in Atlanta ...........................................24<br />

Focal Point on Labor Support: Attachment and Bonding:<br />

The Doula’s Role<br />

By Gillian Sippert .......................................................26<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Helen Young<br />

1936 Garfield Avenue<br />

Ottawa, Ontario K2C 0W8, Canada<br />

Associate Editors<br />

Caroline Brown<br />

Marcella Hart<br />

Columnists<br />

Naomi Bromberg Bar-Yam<br />

Mary Ann Ernzen<br />

Dale King<br />

Ana Lopez-Dawson<br />

Debbie Madonna<br />

Margery Simchak<br />

Kathy Swift<br />

Rebecca Ward<br />

Cover Photo<br />

Kelly Greene<br />

Reviewers<br />

Terry Algire<br />

Cheryl Coleman<br />

Debra Madonna<br />

Pat Turner<br />

This publication printed on<br />

recycled<br />

paper.<br />

Next Issue:<br />

OPEN FOCUS<br />

Editor’s Notes .................................... 2<br />

Letter to the Editor ............................. 2<br />

Across the President’s Desk..................<br />

3<br />

Featured Staff Member ....................... 4<br />

Healthy Lifestyles ............................. 12<br />

Resources ........................................ 13<br />

Statistics .......................................... 16<br />

Focal Point on <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong>:<br />

Clearing Up the Myths<br />

By Patricia Macko ......................................................32<br />

Sample Pages from Postnatal<br />

Curriculum Guide .................................................... 34, 35<br />

Teaching Tips ............................................................... 36<br />

Suggestions for a Doula’s Birth Bag:<br />

ICEA Teaching Ideas Sheet #23<br />

By Jan Mallak ............................................................ 39<br />

COLUMNS<br />

ANNOUNCEMENTS<br />

Information Update .......................... 17<br />

Certification Update .......................... 20<br />

The Internet ..................................... 22<br />

Political Issues .................................. 30<br />

Educator’s Corner ............................. 33<br />

For Your Information ........................ 37<br />

Audio Visual Review ......................... 40<br />

CIMS Feedback Request ...................................................................................... 3<br />

Journal Deadlines ................................................................................................ 4<br />

ICEA Virginia Larsen Research Grant Application Announcement .......................... 23<br />

Web Page Photograph Request .......................................................................... 38<br />

Newly Certified ICCEs, ICDs, ICPEs ...................................................................... 41<br />

Journal Guidelines for Photography .................................................................... 42<br />

ICEA <strong>International</strong> Convention 2000 — Call for Speaker Abstracts ........................ 42<br />

Information for Journal Writers ........................................................................... 43<br />

Change of Address Form ................................................................................... 43<br />

Calendar of Events ............................................................................................ 45<br />

Classified Ad .................................................................................................... 45<br />

Photo Credit: Unless otherwise stated, all photos are<br />

by Caroline Brown, IJCE Associate Editor: Photos.<br />

Articles herein express the opinion of the author. ICEA welcomes manuscripts, artwork, and photographs which will be returned<br />

upon request when accompanied by a self-addressed, stamped envelope. Copy deadlines are February 1, May 1, August 1,<br />

and October 1. Articles, correspondence, and letters to the editor should be addressed to the Managing Editor.<br />

Advertising (classifi ed, display, or calendar) information is available from ICEA. Although advertising is subject to review, acceptance<br />

of an advertisement does not imply ICEA endorsement of the product or the views expressed.<br />

The <strong>International</strong> Journal of <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (ISSN: 0887-8625) is published quarterly and is the offi cial publication<br />

of the <strong>International</strong> <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Association</strong> (ICEA), Inc. Subscriptions are $25 a year, $30 non-US ($20 additional for<br />

airmail). Single copies are $5.<br />

The <strong>International</strong> <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Association</strong>, founded in 1960, unites individuals and groups who support family-centered<br />

maternity care (FCMC) and believe in freedom of choice based on knowledge of alternatives. ICEA is a non-profi t, primarily<br />

volunteer organization that has no ties to the health care delivery system. ICEA membership fees are $30 for individual<br />

members (IM), $100 for supporting members (SM). For group rates write: ICEA, PO Box 20048, Minneapolis, Minnesota<br />

55420-0048 USA.<br />

© Copyright 1998 by ICEA, Inc. Articles may be reprinted only by written permission of the Managing Editor.<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 1

Editor’s Notes<br />

by Helen Young<br />

Recently, a woman called me requesting information<br />

about the prenatal classes at the hospital where I teach.<br />

She said, “I would like to know how much time you<br />

spend on labor and delivery as compared to infant<br />

care. I figure that the labor and birth are going to<br />

happen no matter what I do. What I really want to<br />

learn is how to best take care of my baby.” This type<br />

of inquiry is occurring more and more often lately.<br />

In the past, the main concern of many prospective<br />

parents was how to cope with the pain of labor and<br />

birth. Now with the knowledge that pain medications<br />

are easily accessible at many centres for those who<br />

choose the medicated option, class participants are<br />

often more interested in infant care.<br />

When I was pregnant with my first daughter,<br />

Laura, my colleagues said that I would breeze through<br />

the labor and birth because of my background as a<br />

childbirth educator, but that I wouldn’t have a clue<br />

about how to take care of my baby. Luckily, I was able<br />

to breeze through my labor and birth due to a lot of<br />

preparation, an uncomplicated labor, and excellent<br />

support (my husband always says it was because I had<br />

a great coach). After Laura was born, my husband<br />

and I relied on our instincts and knowledge to deal<br />

with the trials and tribulations of being new parents.<br />

Laura is now a lovely seventeen-year-old, an excellent<br />

student, and very involved in competitive sports and<br />

school activities. I think we did all right.<br />

Postnatal education topics can either be incorporated<br />

into an existing prenatal class program or<br />

offered as a separate series. Mae Shoemaker’s new<br />

Postnatal Curriculum Guide is a timely resource available<br />

through the ICEA Bookcenter. ICEA’s Postnatal<br />

Educator Certification Program is offered for those<br />

who wish to validate their expertise in this field.<br />

This issue of the <strong>International</strong> Journal of <strong>Childbirth</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> focuses on postnatal education. Linda Todd,<br />

in her article “Reciprocal Interaction as the Foundation<br />

for Parent-Infant Attachment,” offers excellent information<br />

regarding the attachment of infant and parent.<br />

The special role of the father in parenting is discussed<br />

in “Parenting: Examining the Father,” by Celestine<br />

West and Marcella Hart. Gillian Sippert examines the<br />

doula’s role in attachment and bonding in the “Focal<br />

Point on Labor Support.” An excellent program<br />

to support new parents is described by Cindy Butler<br />

in her article “It Takes a Village to Raise a Child.” In<br />

the returning Healthy Lifestyles Column, Ana Lopez-<br />

Dawson addresses the issue of abuse in families.<br />

As health care professionals, it is of the utmost<br />

importance that we provide our clients with postnatal<br />

education so that they can adapt well to becoming<br />

parents. We must help them develop confidence in<br />

their abilities to parent and encourage them to trust<br />

in their own instincts. Hopefully, they will then be<br />

able to instill a good sense of self-esteem in their<br />

children — the children who are our future.<br />

Dear Editor<br />

As a childbirth educator certified by the Metropolitan<br />

New York <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

in 1983, I have been reading and benefitting from<br />

the Journal for many years. I read your recent cover<br />

story on labor support and your articles on “doulas.”<br />

I want to clarify some potential confusion created<br />

by your coverage of the topic. Whereas it is true<br />

that DONA (Doulas of North America) began certifying<br />

labor support doulas in the mid-1990s, NAPCS<br />

(National <strong>Association</strong> of Postpartum Care Services), of<br />

which I was a founding member in 1988, has been<br />

certifying postpartum doulas for longer and actually<br />

used the term “doula” for postpartum caregiver<br />

earlier than DONA did for labor supporter. The word<br />

was discovered in a book written by anthropologist<br />

Dana Raphael called The Tender Gift: Breastfeeding and<br />

subtitled Mothering the mother — the way to successful<br />

breastfeeding (Schocken Books 1976). Ms. Raphael<br />

Letter to the Edispoke<br />

at one of NAPCS’ national conferences at a<br />

time when the Klauses and Penny Simkin were developing<br />

DONA.<br />

We are not contesting who has claim to the name<br />

“doula” because women have been helping women<br />

since the beginning of time, and because both types<br />

of doulas “mother the mother” and are honored to<br />

share with her during these most special days of her<br />

life. But I do know that in my own postpartum doula<br />

service, which was incorporated in 1987, there is some<br />

confusion among consumers as to what is meant by<br />

“doula” if they hear that labor support coaches are<br />

also calling themselves doulas. Therefore, I think it<br />

behooves members of our health care professions to<br />

specify “labor support doula” or “postpartum doula”<br />

and not just “doula” as was done in your articles<br />

on labor support. We cannot assume the reader or<br />

consumer will know to which type of doula you are<br />

referring unless you clarify in that way.<br />

Best Wishes, Alice Gilgoff, CNM<br />

Director of Public Relations, National<br />

<strong>Association</strong> of Postpartum Care Services<br />

2 • IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4

Across the President’s Desk<br />

by Cheryl Coleman<br />

“Light tomorrow with today!” says Elizabeth Barrett<br />

Browning. So as the today of 1998 comes to a close, we<br />

focus the light on the year ahead using the glow from a<br />

successful 1998.<br />

ICEA began this year with our biennial transition. The<br />

new ICEA Board of Directors took office in February and<br />

immediately got to work. Once again ICEA participated<br />

in the annual Coalition for Improvement of Maternity<br />

Services (CIMS) conference and shortly thereafter ratified<br />

the Mother Friendly Hospital Initiative. ICEA has also been<br />

quite visible in the professional community during 1998<br />

by exhibiting at the <strong>Association</strong> for Women’s Health,<br />

Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN), American<br />

College of Nurse Midwives (ACNM), and Lamaze <strong>International</strong><br />

conventions as well as the Birth, WIC, and National<br />

<strong>Association</strong> of Childbearing Centers (NACC) conferences.<br />

The ICEA <strong>International</strong> Convention was a success with over<br />

five hundred educators gathering in Atlanta, Georgia. Six<br />

Basic Teacher Training Workshops, one Challenges event,<br />

and three Doula Training Workshops were held this past<br />

year. The Doula Workshop and Certification Program<br />

guidelines were broadened so that even more members<br />

can join this growing, supportive profession. This year<br />

was also a time of celebration and relief for well over two<br />

hundred ICEA members who completed their certification<br />

and now carry the titles of ICCE, CPE, or ICD. Congratulations<br />

to each of you! In addition, ICEA volunteers and<br />

staff have gathered resources, published new materials,<br />

added many new quality books, videos, and teaching aids<br />

to the Bookcenter, and added new columns to the Journal<br />

to meet the needs of our members.<br />

The ICEA Board of Directors and Central Office staff<br />

continue to be busy working for you, the educator. As<br />

we work, we always look at all we do with an eye to the<br />

future. We have determined that we want to maintain<br />

our mission of family-centered maternity care and be<br />

the number one resource for education, certification,<br />

and resources. You are our focus. You are what drives<br />

the programs we offer, the events we exhibit at, and the<br />

publications we develop. We continue to work for you,<br />

but we also need to work with you. Many of you have<br />

received surveys from us in the past year. We thank you<br />

and appreciate your input. We have continued to refer to<br />

the information you have provided as we take the light<br />

of today and look toward a brightly glowing future.<br />

<br />

——— We Welcome Your Feedback ———<br />

The Coalition for Improving Maternity Services (CIMS) has developed<br />

The Mother-Friendly <strong>Childbirth</strong> Initiative<br />

and<br />

The Ten Steps of The Mother-Friendly <strong>Childbirth</strong> Initiative<br />

• Have you used the Initiative or Ten Steps as a model for<br />

change in your community, hospital, birth center, or practice?<br />

• How have you used this document?<br />

• What responses have you received?<br />

• Do you plan to use the documents and how?<br />

Please share your responses with us by sending your comments to:<br />

Pat Turner, ICEA President Elect and CIMS representative,<br />

at ICEA, PO Box 20048, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55420 USA,<br />

or her e-mail address: paturner@ctel.net<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 3

Featured Staff Member<br />

Dale King, Statistics Columnist for the <strong>International</strong> Journal of <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, received his doctorate in<br />

Economics from the State University of New York at Albany in 1995. His dissertation was concerned with the<br />

impact of socioeconomic, organizational, and professional liability factors on the odds of cesarean delivery.<br />

Part of his research was published in the August 1994 issue of the Journal of the American Medical <strong>Association</strong><br />

and presented at an international conference on health policy and management. The central thesis<br />

of his work was that women have begun to educate themselves so that they may have their desired birth<br />

experience rather than let their physician make all the necessary decisions. For example, better educated<br />

women were at the forefront of the increase in the vaginal birth after cesarean rate that occurred in the<br />

late nineteen eighties.<br />

Dale’s Statistics Column has appeared in the <strong>International</strong> Journal of <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> for the past two<br />

years. He is currently employed as an analyst for the New York State Department of Health.<br />

The <strong>International</strong> Journal of <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> welcomes your<br />

articles and photos (authors and photographers must submit<br />

a signed copy of the submission statement included in Information<br />

for Journal Writers) for the next four issues.<br />

They can be sent to Managing Editor Helen Young,<br />

1936 Garfield Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K2C 0W8 CANADA;<br />

e-mail address: ag139@freenet.carleton.ca.<br />

June 1999: “Infant Feeding”<br />

February 1, 1999 Deadline<br />

September 1999: “Your Practice”<br />

May 1, 1999 Deadline<br />

December 1999: “Turn of the Century”<br />

August 1, 1999 Deadline<br />

March 2000: “Open Focus”<br />

October 1, 1999 Deadline<br />

Writers are also encouraged to submit articles for Journal’s<br />

Focal Points, as they relate to each particular issue focus.<br />

Focal Point on Breastfeeding<br />

Focal Point on <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

Focal Point on Labor Support<br />

Focal Point on Postnatal <strong>Education</strong><br />

4 • IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4

Reciprocal Interactions as the<br />

Foundation for Parent-Infant Attachment<br />

At a recent gathering of<br />

new parents, a mother<br />

admiring her four-week-old<br />

baby said, “I talk to her all of<br />

the time, but sometimes I feel<br />

like<br />

I must be crazy because, you<br />

Where did the baby fit into this statement? This was<br />

obviously a loving parent. The emergence of the social<br />

smile in her baby would certainly awaken this mother<br />

to the reciprocal nature of interactions that were already<br />

going on. Still, her comment represents pervasive, cultural<br />

messages that we are not fully human — not really<br />

there — until we can speak for ourselves. Central to any<br />

healthy relationship is the belief that we will be heard.<br />

What can educators and health care professionals do to<br />

support an awareness of reciprocity from the beginning<br />

of this most central of human relationships?<br />

Sensory development in the prenatal period allows the<br />

baby to engage the environment socially at birth —and<br />

before. The tactile sense is the first to develop prenatally<br />

and the most refined sense at birth. Auditory development<br />

is completed during the prenatal period. Once any remaining<br />

amniotic fluid is absorbed, the newborn’s hearing is<br />

as good as an older child’s. Auditory ability gives us the<br />

A<br />

by Linda Todd<br />

clearest picture of prenatal learning. Newborn babies show<br />

a marked preference for voices heard during the prenatal<br />

period. DeCasper and Spence (1986) demonstrated that<br />

babies recognize a story read to them twice a day in the<br />

last six weeks of pregnancy when compared to an unfamiliar<br />

story that was heard for the first time after birth.<br />

Furthermore, the unborn baby often habituates to sounds<br />

that might be considered disturbing, for example, barking<br />

of a family dog or airplanes flying overhead, showing a<br />

remarkable ability to filter these sounds out after birth.<br />

At birth, the newborn’s sense of taste is acute. Babies<br />

show a preference for sweet over sour tastes (Lipsitt 1977).<br />

Rosenstein and Oster (1988) demonstrated that when<br />

exposed to the taste of various substances, newborns<br />

made facial expressions very much like adults exposed<br />

to the same tastes, providing evidence that such facial<br />

expressions are innate. Like the sense of taste, the sense of<br />

smell is well developed at birth. In a time frame of thirty<br />

to ninety minutes after birth, newborns exposed to the<br />

odor of amniotic fluid cry significantly less than controls<br />

or even those exposed to breastmilk (Varendi et al. 1998).<br />

In the first days after birth, newborns distinguish between<br />

the natural odor of the maternal breast and a breast that<br />

has been washed, showing a preference for the natural<br />

odor breast (Varendi, Porter, and Winberg 1997).<br />

The least well-developed sense of the baby at birth<br />

is vision. Newborns are remarkably nearsighted, creating<br />

something of a visual cocoon for the first several weeks.<br />

During that time, the human face captures attention. Stern<br />

(1977) has speculated that in this world of limited vision,<br />

the infant learns to read the nonverbal messages of the<br />

human face in ways that might<br />

not otherwise occur.<br />

Nearly as impressive as<br />

sensory development is motor<br />

development in the prenatal<br />

period. By twenty weeks of<br />

pregnancy, the unborn baby is<br />

capable of all the movements<br />

that will be seen after birth<br />

(Comparetti 1981). The early<br />

development of the vestibular<br />

system of the middle ear,<br />

around four months, allows the<br />

unborn baby to sense changes<br />

in maternal posture as he floats<br />

in the amniotic fluid (Patten<br />

1968). Women frequently comment<br />

on increased fetal move-<br />

continued on page 6<br />

Dan Hammond<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 5

RECIPROCAL INTERACTIONS AS FOUNDATION FOR ATTACHMENT from page 5<br />

ment when lying down. After birth, women find great<br />

pleasure in watching movements of their newborns and<br />

relating them to sensations of pregnancy. Such observations<br />

probably have an effect on integrating attachment<br />

feelings for the fetus, the baby imagined in pregnancy,<br />

and the real baby (Brazelton and Cramer 1990).<br />

Much of the unborn and newborn baby’s movement<br />

is reflexive in nature. These reflexes allow babies to respond<br />

to and act on the world around them (Cole and<br />

Cole 1993). For example, the crawling reflex may play a<br />

role in the baby’s descent during labor. Bringing the hand<br />

to the mouth and sucking can be observed frequently<br />

throughout the prenatal period. After birth, this skill is an<br />

important component of infant self-comforting. Movement<br />

is, of course, a measure of fetal well-being. Introducing<br />

the idea of fetal movement counts, as a way of spending<br />

time with the baby to affirm wellness, supports a central<br />

component of healthy parenting: paying attention. This is<br />

more holistic than recommending fetal movement counts<br />

solely as a way to identify a potential problem. It is hard<br />

to engage in social discourse when all you are listening<br />

for is bad news.<br />

Just as before birth, the foundations of attachment<br />

work between parent and baby after birth are largely<br />

sensory. To the interaction, the baby brings all of the<br />

sensory and motor skills developed during the prenatal<br />

period. The quiet alert state into which babies are born<br />

allows them to demonstrate not only that they can see,<br />

hear, feel, and smell their parents, but that it is their parents’<br />

voices, touch, faces, and odors that are preferred. A<br />

newborn recognizes the sound of the mother’s or father’s<br />

voice, turns towards it, scans the environment visually<br />

to find that familiar person, and often orients the body<br />

toward the parent. When in a parent’s arms, the baby<br />

nestles in, clings with the grasp reflex, and roots to find<br />

the comfort of suckling. New parents bring the same<br />

sensory awareness to their babies. The very appearance<br />

of the newborn draws out nurturing responses: head large<br />

6 • IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4<br />

B<br />

in proportion to the rest of the body, rounded forehead,<br />

large eyes, and round, full cheeks all make giving over<br />

to the needs of the baby easier (Lorenz 1943). In the<br />

first days after birth, mothers recognize their newborns<br />

readily by odor (Porter, Cernoch, and McLaughlin 1983).<br />

This primal sensitivity heightens awareness of the baby<br />

in ways that baby books and parenting classes cannot.<br />

Baby observation becomes a full-time job. The intensity of<br />

this observation is reflected in the questions asked about<br />

physical appearance, newborn behaviors, and caretaking<br />

skills. As professionals, it is easy to overlook the meaning<br />

of these questions. For the parents, the ability to distinguish<br />

between normal and abnormal, what to expect, and<br />

how to respond are literally issues of life and death. The<br />

shadow side of the attachment work going on is fear of<br />

loss. Taming the monsters of those fears is a large part<br />

of the work of postpartum, learning to believe in one’s<br />

ability to parent in such a way that both parent and baby<br />

will survive and thrive.<br />

Professionals can assist parents in beginning awareness<br />

of the reciprocal nature of interactions with their<br />

babies by talking with them, both before and after birth,<br />

about their babies’ emerging sensory-motor skills. Even<br />

well-educated parents who have seen the unborn baby<br />

several times on sonogram, know the sex of the baby, or<br />

have named the baby are often surprised to learn that<br />

babies are born innately social — and that social interaction<br />

begins before birth. Many parents have not brought<br />

to conscious awareness the reality that their baby has<br />

sensory competencies before as well as after birth.<br />

Questions such as the following, asked during pregnancy,<br />

invite parents to notice the reciprocal nature of<br />

interactions occurring with their babies:<br />

• When is the baby most active?<br />

• D o c e r t a i n p o s i t i o n s y o u<br />

are in change the baby’s activity?<br />

• Does your baby move differently when it has been<br />

a while since you have eaten<br />

or right after a meal?<br />

• Are you becoming more<br />

aware of the baby’s sleep<br />

and awake pattern? What is<br />

that pattern like?<br />

• Does the baby seem to respond<br />

differently to different<br />

voices. For example, what<br />

happens when the baby is<br />

moving and you call your<br />

partner (or a sibling) closer<br />

to watch?<br />

• Are there any sounds your<br />

baby seems to like, such as a<br />

certain type of music? Have<br />

you noticed the baby startle<br />

or become almost overactive<br />

in response to any sounds?<br />

When the baby is active and<br />

you (your continued partner, on a sibling)<br />

page 7

RECIPROCAL INTERACTIONS AS FOUNDATION FOR ATTACHMENT from page 6<br />

D<br />

C<br />

stroke the abdomen, what does the<br />

baby do? Is the baby’s response different<br />

depending on who strokes your<br />

abdomen?<br />

As professionals, our own awareness of<br />

the sensory foundations of the parent-infant<br />

relationship should serve as a basis for our<br />

care of newly forming families after birth.<br />

Parents and babies cannot benefit from the<br />

innate skills and drives each brings to the<br />

interaction if they are apart. While it is true<br />

that parents and babies can look forward<br />

to a lifetime together, what occurs between<br />

parent and baby in the first minutes, hours,<br />

and days after birth is not like any other time.<br />

Complications requiring parents and babies<br />

to be apart can be accepted and integrated,<br />

but few parents would say such separation<br />

makes things easier in taking on the parent-<br />

ing role.<br />

It is still common for newborns to be delivered into<br />

the hands of a physician who gives the baby to a nurse<br />

who assesses the baby, gives a Vitamin K injection, places<br />

ointment in the newborn’s eyes, and occasionally even<br />

bathes the baby before the baby is brought to the parents.<br />

Nothing in our knowledge of what Stern (1977) calls<br />

the biologically designed choreography between parent<br />

and child would suggest this is the best course of care.<br />

Postpartum care practices that result in babies going to a<br />

nursery for initial care, lab work, pediatrician visits, and<br />

to spend the night are not based on the best available<br />

research on postpartum physiological or psychological<br />

adaptation. It is common to hear postpartum staff say<br />

that many parents don’t want their babies with them all<br />

of the time. When new parents believe that having their<br />

babies with them in the immediate postpartum means<br />

they are solely responsible for newborn care, it is not<br />

surprising that they ask to have their babies taken from<br />

their sides.<br />

Parents are often told that having their babies with<br />

them throughout hospitalization allows them to learn how<br />

to care for the baby. This really misses the point of keeping<br />

parents and babies together, is an unlikely outcome<br />

given the scope of the task of learning caretaking, and<br />

overlooks the parents’ own needs to be cared for. Keeping<br />

parents and babies together is important because for<br />

the vast majority of families, being together best supports<br />

physical, emotional, and social well-being of the new family<br />

members. In truly family-centered environments, staff<br />

believe that the safest place for babies is with parents.<br />

They also believe that for new parents to benefit from<br />

being with their infants, they need help — both in caring<br />

for the babies and for themselves.<br />

Birth facilities that get what is happening between<br />

parent and baby keep them together by providing care<br />

to the entire family unit in a single room. The nurse<br />

providing care is an expert on all members of the new<br />

family. Provision is made for fathers or other important<br />

people to the mother to stay throughout the period of<br />

hospitalization. Such important people are not simply<br />

provided a bed but have their own needs acknowledged<br />

and their significance to the baby affirmed in practical<br />

ways. Newborn assessments, basic care, lab work,<br />

and physician exams are done at the bedside or in the<br />

arms of the parent. All staff recognize that being close<br />

to parents makes these experiences less stressful for the<br />

newborn and are teachable moments for the family. In<br />

a family-centered environment, professionals are aware<br />

that they are modeling interactions with the baby. They<br />

introduce themselves to the baby, acknowledge infant<br />

responses to interactions and cues, and help parents<br />

translate infant behavior into infant language.<br />

In this type of family-centered environment, a crying<br />

baby is not viewed as someone to be banned to a nursery,<br />

but as a distressed human who is telling us about a problem.<br />

Finding ways to comfort the baby with the parents<br />

provides a learning opportunity that is of great importance<br />

continued on page 8<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 7

RECIPROCAL INTERACTIONS AS FOUNDATION FOR ATTACHMENT from page 7<br />

to every new family. Frequently, newborn crying is due<br />

to feeling alone. Swaddling and placing the baby in bed<br />

with mother or father often results in everyone getting<br />

some rest. For parents, the message is, “I am important<br />

to this baby. I am what the baby needs.” This is both the<br />

joy and burden of parenting. Realizing that parenting is<br />

about presence is crucial in the development of healthy<br />

families.<br />

When caring for parents and babies together, skilled<br />

staff can help parents see that crying is often a last step<br />

in a baby’s communication process rather than the baby’s<br />

sole way of communicating. Together, parent and professional<br />

can watch for the subtler messages that every<br />

newborn offers as a sign help is needed. Messages may<br />

include a change in state of consciousness, averting visual<br />

attention as a sign a break is needed, raising a hand in<br />

front of the face as a way of showing that the interaction<br />

is overwhelming, efforts to establish eye contact as a way<br />

to initiate conversation, and rooting or batting the face<br />

with the hands as evidence of hunger. In the old model<br />

of rooming-in where parents assumed full responsibility<br />

for the care of the baby, this kind of learning occurred by<br />

chance — if at all — rather than by practice. When parents<br />

and babies are cared for together, teaching flows naturally<br />

from moments when the nurse is caring for the baby, the<br />

parent, or both rather than being driven by checklists<br />

that seem unrelated to competencies a parent actually<br />

needs.<br />

Finally, in a family-centered environment, visitors are<br />

present at the wishes of the parents and are educated<br />

about their role in getting this family off to a good start.<br />

Staff recognize that the health care system has limited<br />

resources and limited time with new parents, but know<br />

families that thrive have quality social support. Built into<br />

practice, then, is a valuing of those who come to celebrate<br />

the addition of a new member of the community.<br />

Basic to our hopes for babies and parents is that<br />

they form relationships that sustain them throughout life.<br />

Healthy relationships form when there is mutually satisfying<br />

reciprocal interaction. That is true of parents and babies,<br />

parents and the staff who care for them, and parents and<br />

institutions in which every new family is treated as the<br />

F<br />

community’s greatest natural resource.<br />

References<br />

E<br />

Brazelton, T. B. and B. G. Cramer. 1990. The earliest relationship: Parents,<br />

infants and the drama of early attachment. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley<br />

Publishing Company, Inc.<br />

Comparretti, M. 1981. The neurophysiologic and clinical implications<br />

of studies on fetal motor behavior. Seminars in Perinatology May 5<br />

(2): 183-189.<br />

Cole, M. and S. R. Cole. 1993. The development of children. 2nd ed.<br />

New York: Scientific American Books.<br />

DeCasper, A. J. and M. J. Spence. 1986. Prenatal maternal speech inferences<br />

newborns perception of speech sounds. Infant Behavior and<br />

Development 9: 133-150.<br />

Lipsitt, L. P. 1977. “Taste in human neonates: Its effects on sucking<br />

and heart rate.” In Taste and development: The genesis of sweet preference,<br />

edited by J. M. Eiffenbach. Washington, DC: U. S. Government<br />

Printing Office.<br />

Lorenz, K. 1943. Die Angebornen Formen mogicher Erfahrung. Zeitschrift<br />

Fur Tierpsychologie 5: 233-409.<br />

Patten, B. M. 1968. Human embryology. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-<br />

Hill.<br />

Porter, R. H., J. M. Cernoch, and F. J. McLaughlin. 1983. Maternal<br />

recognition of neonates through olfactory cues. Physiological Behavior<br />

1: 151-154.<br />

Rosenstein, D., and H. Oster. 1988. Differential facial responses to four<br />

basic tastes in newborns. Child Development 59: 1555-1568.<br />

Stern, D. 1977. The first relationship: Infant and mother. Cambridge:<br />

Harvard University Press.<br />

Varendi, V. H., K. Christensson, R. H. Porter, and J. Winberg. 1998.<br />

Soothing effect of amniotic fluid smell in newborn infants. Early Hu-<br />

man Development<br />

51, no. 1: 47-55.<br />

Varendi, V. H., R. H. Porter, and J. Winberg. 1997. Natural<br />

odour preferences of newborn infants change over time.<br />

Acta Paediatr 86, no. 9: 985-990.<br />

■ Linda Todd, BA, MPH, ICCE, is the author of You and Your<br />

Newborn Baby: A Guide to the First Months After Birth, as<br />

well as ICEA’s publication, Labor and Birth: A Guide for You.<br />

She is currently a Consultant and Coordinator of <strong>Education</strong>al<br />

Services for Phillips+Fenwick, a California-based women’s health<br />

services consulting firm.<br />

<br />

8 • IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4

ICEA ALTERNATE CONTACT HOURS PROGRAM #26<br />

Reciprocal Interaction as the Foundation for Parent-Infant Attachment<br />

To receive one ICEA Contact Hour, read Reciprocal Interaction as the Foundation for Parent-Infant Attachment,<br />

circle the correct answers on the self-test, submit completed self-test and application with payment. Contact Hours<br />

purchased and earned from this program are valid for the current certifi cation period for TCP candidates, the current<br />

recertifi cation period of ICCEs or ICPEs, as well as for any individual who is a member of an outside organization<br />

that accepts ICEA Alternate Contact Hours. Send application with completed self-test and appropriate payment to:<br />

ICEA Alternate Contact Hours, PO Box 20048, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55420 USA. Telephone 612/854-8660; Fax<br />

612/854-8772. Applications and completed self-test may be faxed if using a Visa or MasterCard.<br />

1. The pervasive cultural message is that we are not fully human — not really there — until:<br />

a. birth<br />

b. seven months of gestation<br />

c. we understand what is being said<br />

d. we can speak for ourselves<br />

2. The most refi ned sense at birth is:<br />

a. hearing<br />

b. smell<br />

c. touch<br />

d. vision<br />

3. Newborn babies show a marked preference for:<br />

a. nursery rhymes<br />

b. classical music<br />

c. voices heard during the prenatal period<br />

d. rock music<br />

4. Women frequently comment on increased fetal movement:<br />

a. after exercising<br />

b. while laughing<br />

c. while standing<br />

d. when lying down<br />

5. Frequently, newborn crying is due to:<br />

a. pain<br />

b. cold<br />

c. feeling alone<br />

d. being hungry<br />

6. In the older model of rooming-in, learning occurred:<br />

a. by regular instructions from the nurses<br />

b. by chance<br />

c. never<br />

d. rarely<br />

continued on page 10<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 9

7. In a family-centered environment, visitors are valued because:<br />

a. families thrive on social support<br />

b. nurses don’t have time to do all the care<br />

c. visitors bring gifts<br />

d. new parents need someone to keep them occupied<br />

8. It is important that babies and parents form relationships that sustain them:<br />

a. for the fi rst year<br />

b. throughout life<br />

c. for the fi rst fi ve years<br />

d. until breastfeeding is well established<br />

9. The unborn baby is capable of all movements that will be seen after birth, by _______ weeks.<br />

a. 20<br />

b. 16<br />

c. 24<br />

d. 12<br />

10. Babies show a taste preference for:<br />

a. sour over salty<br />

b. salty over sweet<br />

c. sweet over sour<br />

d. sweet over salty<br />

Date ___________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Name __________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Address ________________________________________________________________________________<br />

City ______________________________________________ State/province _______________________<br />

Postal/zip code _________________________ Country ________________________________________<br />

Telephone ______ / _____________________<br />

ICEA membership number (if you are a member) _________________________<br />

(include expiration date)<br />

Payment of $10 in US funds (ICEA members), $20 in US funds (non ICEA members), check and drafts drawn<br />

on US banks only or Visa or MasterCard. You must include membership number if paying member rate.<br />

Visa/MasterCard Number _____________________________________<br />

Expiration Date _______________<br />

Signature _______________________________________________________________________________<br />

I am in the following ICEA certifi cation program(s):<br />

_____ Teacher Certifi cation _____ Postnatal Educator Certifi cation ____ Doula Certifi cation<br />

Contact hours earned from this program are valid only for the current certifi cation period for ICEA certifi cation<br />

candidates or the current recertifi cation period for ICEA certifi ed educators and doulas.<br />

Send application and completed self-test with payment to:<br />

ICEA Alternate Contact Hours, PO Box 20048, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55420 USA.<br />

Telephone 612/854-8660; Fax 612/854-8772.<br />

12/98<br />

10 • IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4

It Takes a Village to Raise a Child<br />

by Cindy Butler<br />

CIt is also an absorbing and sometimes taxing experience for<br />

parents, child care providers, and other family members.<br />

Parents and child care providers want to give their children<br />

the best, so when they have questions and concerns, they<br />

need resources to provide them with information, insight,<br />

and reassurance. Family members play a role here as<br />

do health and child care professionals, teachers, books,<br />

and the internet. A telephone resource answered by a<br />

well-informed, empathetic professional can be a helpful<br />

adjunct and can provide on-the-spot, objective, and, if<br />

desired, anonymous help to clarify a situation or increase<br />

understanding of a child’s behavior.<br />

“My eighteen-month-old boy hit and kicked me this<br />

aring for children, for the most part, is a joy<br />

and a source of great satisfaction.<br />

morning when I tried to bring him inside from playing<br />

at the park. He broke my glasses (sounds of sobbing).”<br />

The Child Advice Warm Line in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada<br />

is here to reassure this mother that her child was express-<br />

ing frustration at having to end his fun playtime and did<br />

not consciously intend to break her glasses or to hurt her.<br />

Tips to try for next time might include preparing the child<br />

ahead of time to go inside, focusing the child on a<br />

pleasant task that needs to be done once inside, and<br />

asking him to carry something. The mother could take<br />

some deep cleansing breaths to help her maintain her<br />

cool, and she could try to avoid having the toddler get<br />

overly hungry or fatigued. Sometimes these suggestions<br />

are a reminder, and other times this is the introduction<br />

into life with a busy, independent toddler. Calls often<br />

end with the Warm Line worker stating that “it sounds<br />

like you are doing a very good job with this child” or<br />

“you sound like a wise and sensitive parent.” At this, the<br />

caller often sighs and says, “Thank you. I don’t hear that<br />

very often.”<br />

Parents of older babies and pre-schoolers make up<br />

the majority of callers, followed by those with schoolage<br />

children and teenagers. “Is this normal?” is a fairly<br />

typical refrain. Dispensing information on resources in<br />

the community and how to access them is an important<br />

contribution of the professional.<br />

<strong>Childbirth</strong> education focuses on postnatal support<br />

of new families in the early hours, days, and weeks of<br />

a baby’ s life. The Child Advice Warm Line (CAWL) can<br />

and does address this period but extends support to the<br />

first eighteen years of life. CAWL was developed in 1989<br />

within the Children’s Village of Ottawa-Carleton, a licensed<br />

home child care agency, to provide parents and child care<br />

providers in the community with a resource that in kind<br />

is like the “Home Visitor” who is available to home child<br />

care providers and parents of children in the program.<br />

The line operates seventeen hours a week — Monday 4:00<br />

P.M. to 9:00 P.M. and Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday<br />

12 noon to 4:00 P.M. The noon hour and evening hours<br />

provide an opportunity to phone outside of regular working<br />

hours. The Warm Line is funded and administered<br />

through the Children’s Village of Ottawa-Carleton. Standing<br />

independently from a health care agency and within the<br />

framework of a child care agency broadens the scope of<br />

concerns that can be addressed.<br />

The choice of name was a difficult decision. Originally<br />

it was hoped that the acronym CAWL would catch on, but<br />

it often is more likely to be referred to as “the Warm Line.”<br />

Other organizations seem to use the warm line concept and<br />

name to refer to a source of support for every day con-<br />

cerns that are not<br />

emergencies. The<br />

Child Advice Warm<br />

Line recognizes<br />

that raising children<br />

is hard work<br />

and caregivers of<br />

children<br />

need more help<br />

with the “downs” than<br />

with the “ups.”<br />

“The first years last forever” (Canadian Institute of<br />

Child Health 1998), and that is the compelling reason to<br />

provide caregivers of children with information, reassurance,<br />

encouragement, and resources. It is of the utmost<br />

importance and the Child Advice Warm Line helps to<br />

provide this service.<br />

References<br />

Reiner Foundation. 1998. The first years last forever. Pamphlet is part<br />

of the “I AM YOUR CHILD” campaign. Ottawa: Canadian Institute of<br />

Child Health.<br />

■ Cindy Butler, RN, BSN, is a childbirth educator with the Ottawa Hospital<br />

– Civic Campus Prenatal Program and coordinates and answers the Child Advice<br />

Warm Line at the Children’s Village of Ottawa-Carleton, Canada. She has been<br />

involved with prenatal and parenting education for many years as a teacher,<br />

a nurse in a paediatrician’s office, and a La Leche League leader. Cindy is the<br />

mother of two children and grandmother of seven-month-old Ansel who was<br />

born (naturally) to her daughter and son-in-law in Tokyo, Japan.<br />

<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 11

HEALTHY LIFESTYLES<br />

by Ana Lopez-Dawson<br />

When Parenting Hurts<br />

As an ICEA Certified <strong>Childbirth</strong> Educator and Licensed<br />

Clinical Psychologist specializing in the area of abuse and<br />

neglect, I have had the opportunity to meet with many<br />

families and individuals before, as well as after, the birth of<br />

their child. It is fascinating for me to observe how different<br />

a parent might behave from their self- perception.<br />

While an individual may consider themselves an<br />

adequate parent, the interaction between parent and<br />

child may suggest serious problems in their relationship.<br />

Although in a single year more than 1,500,000 American<br />

children may be neglected or abused, and many of<br />

those children will die as a result of their maltreatment<br />

(US Department of Health and Human Services 1988),<br />

it is difficult for many parents to perceive themselves as<br />

abusive or having the potential for being abusive. I believe<br />

the reason stems from the fact that many abusive parents<br />

have great difficulty recognizing their weaknesses, and<br />

some refuse to take responsibility for their actions. Abusive<br />

individuals come from all walks of life and backgrounds,<br />

and thus, for professionals, it can be difficult to detect<br />

an abusive parent if the abuse is subtle and not blatant.<br />

Even very abusive parents can be observed to be loving<br />

and affectionate with their children intermittently.<br />

It is the general belief that there are several factors<br />

which place a child at higher risk for being abused. Certain<br />

vulnerabilities in the parent, such as psychopathology<br />

and substance abuse, place that parent at higher risk to<br />

abuse their child. Depression, for example, can be quite<br />

debilitating, particularly during the postpartum period.<br />

One might see a parent who is struggling unsuccessfully<br />

to take care of their needs while also trying to meet those<br />

of their infant. Symptoms such as sleep deprivation and<br />

increased irritability are not unusual during a depressive<br />

episode. This problem can be compounded further<br />

during the postpartum period when sleep deprivation is<br />

present by nature due to the infant’s feeding and sleep<br />

patterns. These factors place the infant at increased risk<br />

for abuse.<br />

Alcohol and drug abuse (methamphetamine in particular)<br />

seem to be a prevalent problem, particularly in<br />

the families with whom I work. In a substantial amount<br />

of cases, the baby is removed from the home at the time<br />

of its birth due to prenatal drug exposure. As one can<br />

imagine, the early separation and subsequent lack of quality<br />

on-going contact with the infant substantially impact<br />

the bonding and attachment process for the child and the<br />

parents. Most of the time, these parents lack the coping<br />

skills necessary to care for their child. Additionally, some<br />

individuals may have secondary brain-related deficits, as<br />

a direct result of their substance abuse, further limiting<br />

their ability to parent. Early intervention is crucial in these<br />

families.<br />

Factors in the child which may increase their potential<br />

for abuse include a strong temperament and certain vulnerabilities<br />

such as mental retardation, physical disability,<br />

low birth weight, or other factors which may present as<br />

a special challenge to the parent in caring for that child.<br />

Certain developmental stages such as the terrible twos or<br />

adolescence can prove particularly challenging for parents.<br />

Often, a lack of awareness on behalf of the parent<br />

about what is normal behavior for a child at a certain<br />

developmental stage causes much of the problem. For<br />

example, I have worked with parents who perceived their<br />

two-year-old as purposefully trying to push their buttons.<br />

Teaching these parents that a normal two-year-old is supposed<br />

to be oppositional can help to reduce the parents’<br />

level of anger, their sense of helplessness, and possibly<br />

reduce some of the risk for abuse.<br />

Parents with handicapped children are often exhausted<br />

physically and mentally from caring for their children. It is<br />

not at all unusual for them to feel guilt-ridden over their<br />

child’s disability (even if it was not a result of their own<br />

prenatal neglect) or to have a sense of helplessness. Their<br />

sense of failure as a parent may lead to abuse, which in<br />

turn would increase their sense of helplessness. Finally,<br />

many families experience a deep sense of loss over not<br />

having had their expected outcome. Their child’s future<br />

might be looked at with fear or worry.<br />

The temperament of the child is also a crucial factor.<br />

In my practice, I have worked with parents who were<br />

well-equipped with parenting skills and social supports,<br />

lacked a history of psychopathology, and were drug-free.<br />

However, their child’s temperament was so challenging<br />

that the parents would run out of stamina and patience.<br />

Some of these children may struggle when they experience<br />

a change in their environment. Transitioning from one<br />

activity to the next may require much preparation and it<br />

needs to be done in a gradual fashion. This requires the<br />

parent to have adequate planning ability and an awareness<br />

of environmental deviations. It is time-consuming<br />

and extremely draining on one’s energy.<br />

Finally, there are social factors which place families<br />

at risk. These include those at or below the poverty level,<br />

limited or the absence of social support, being a single<br />

parent, having four or more children, younger parental<br />

age, family violence, acculturation difficulties, and stressful<br />

events (US Department of Health and Human Services<br />

1988). One might see several families living in a small<br />

apartment or cubicles because of lack of resources. There<br />

are also many families who may not be of legal immigration<br />

status who cannot tap into certain community financial<br />

continued on page 13<br />

12 • IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4

RESOURCES<br />

by Rebecca Ward<br />

This Resources Column will offer information on low-cost<br />

resources for parents and professionals. The emphasis will<br />

be on resources for the postpartum period, including<br />

parenting and promoting healthy babies and mothers.<br />

Expectant and new parents trust childbirth educators<br />

and other health professionals for valid information.<br />

When preparing parents for the fourth trimester of the<br />

childbearing year, educators need to be knowledgeable<br />

about current resources and help parents be discerning<br />

consumers of information. New parents are inundated<br />

with information, from the verbal advice of friends to<br />

an avalanche of books. Now the global internet has<br />

broadened access to information — both good and not<br />

so good. Parents need to determine what sources are<br />

reputable, reliable, and consistent with scientific knowledge<br />

of health and child development. In keeping with these<br />

goals, the ICEA Bookcenter offers the catalog Bookmarks,<br />

which includes books, videotapes, and teaching aids<br />

dealing with childbirth, family-centered maternity care,<br />

breastfeeding, and early child care. Titles include Bonding<br />

by Klaus, Kennell, and Klaus, Touchpoints — The Essential<br />

Reference by Brazelton, and Your Baby and Child<br />

by Leach.<br />

Professionals and parents can contact the ICEA Bookcenter<br />

by phone at 800/624-4934 or by fax at 612/854-8772.<br />

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS (AAP) The AAP<br />

issues policy statements on dozens of issues regarding<br />

infants and children. Example: Breastfeeding and the Use<br />

of Human Milk (RE9729). 1997. Pediatrics 100, no. 6:<br />

1035-1039. The journal Pediatrics is published by the AAP.<br />

Access to policy statements is free of charge at website:<br />

http://www.aap.org/policy/pprgtoc.html#I. To request a<br />

subscription or have articles faxed or mailed (at a charge),<br />

contact AAP, 141 NW Point Boulevard, Elk Grove Village,<br />

IL 60007 USA; phone 847/228-5005.<br />

BABYCENTER.COM This is the most complete online<br />

resource for pregnancy and baby information continued on you page can 14<br />

HEALTHY LIFESTYLES: WHEN PARENTING HURTS from page 12<br />

resources, and as a result, the families (and children in<br />

particular) suffer substantially.<br />

Parents who themselves have witnessed or have been<br />

the recipients of abuse are at increased risk of abusing their<br />

offspring. It has been estimated that approximately onethird<br />

of individuals who have been physically or sexually<br />

abused or severely neglected will mistreat their children<br />

(Kaufman and Zigler 1987). Single parents in particular<br />

are at high risk (Arbuthnot and Gordon 1996) due to the<br />

combination of being overwhelmed with responsibility<br />

and not having as much opportunity for regenerating<br />

their battery as may otherwise be the case in a two-parent<br />

household.<br />

Social support is crucial for high-risk families. I become<br />

particularly concerned when I observe a parent who is<br />

abusive, has limited or no resources, and is isolated from<br />

others. While some may agree (or disagree) that it takes<br />

a village to raise a child, social support and community<br />

unity truly have a positive role in helping families function<br />

in a healthier manner. Some cultures are better equipped<br />

at offering this support than others.<br />

As childbirth educators, we are very fortunate in that<br />

we have access to a woman during her pregnancy. We<br />

often also have intermittent contact with the father as<br />

well. This can allow us the opportunity to identify at-risk<br />

families with whom we can intervene in order to help<br />

deter future problems with abuse. Families who are in<br />

crisis benefit significantly from having contact with caring<br />

and sensitive educators and professionals who are<br />

not judgmental. It is important to be in tune with the<br />

fear that many parents have that if they disclose family<br />

violence, they can risk losing their children. It is helpful<br />

to be knowledgeable about the laws and procedures in<br />

one’s geographic area with regards to how these cases<br />

may be handled in order to better guide the parents with<br />

whom we have contact.<br />

Certainly, abuse of any kind is a tragedy and something<br />

which should not occur. As advocates for families, I<br />

challenge and encourage you to continue to take a proactive<br />

stance in helping parents and their children. This will<br />

allow families to empower themselves with information<br />

and resources so that they can thrive both physically and<br />

emotionally. There are numerous resources available in the<br />

community which are geared to helping families function<br />

at a higher level. Further information may be available<br />

through your local human services office or other similar<br />

facility.<br />

References<br />

Arbuthnot, J. and D. Gordon. 1996. What about the children: A guide for<br />

divorced parents. Athens, Ohio: The Center for Divorce <strong>Education</strong>.<br />

Kaufman, J. and Zigler E. 1987. Do abused children become abusive<br />

parents? American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry 57: 187-192.<br />

US Department of Health and Human Services. 1988. Study findings:<br />

Study of the national incidence and prevalence of child abuse and neglect.<br />

Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.<br />

■ Ana M. Lopez-Dawson, PhD, PsyD, ICCE, works at Clinical Assessment &<br />

Treatment Services located in West Des Moines, Iowa, USA.<br />

<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 13

RESOURCES from page 13<br />

trust for the parents in your practice. Written by parenting<br />

experts and reviewed by doctors and other health<br />

professionals, the Resource Center offers an A-Z guide to<br />

preconception, pregnancy, and baby’s first years. With<br />

features such as bulletin boards, personal pages, and help<br />

with naming baby, this website offers professional support<br />

to a community of parents. A lot of fun and information<br />

can be shared with your childbirth education classes.<br />

Website: http://www.babycenter.com<br />

BABYWISE BOOK CAUTION The book On Becoming Babywise<br />

has raised concerns among pediatricians because it<br />

outlines an infant-feeding program that has been associated<br />

with failure to thrive, poor weight gain, dehydration, breast<br />

milk supply failure, and involuntary weaning. A hospital<br />

review committee in Winston-Salem, North Carolina has<br />

listed eleven areas in which the program is inadequately<br />

supported by conventional medical practices. Dr. Matthew<br />

Aney states that “efforts should be made to inform parents<br />

of the AAP recommended policies for breastfeeding and in<br />

potentially harmful consequences of not following them”<br />

(Aney, M. 1998. AAP News (the official news magazine<br />

of the American Academy of Pediatrics) 14, no. 4). Colleen<br />

Weeks, CCE, and member of ICEA, co-chaired a task<br />

force of the Child Abuse Prevention Council of Orange<br />

County, California which conducted a detailed investigation<br />

of Growing Families <strong>International</strong> (GFI) materials. On<br />

Becoming Babywise is a GFI publication. Colleen stated,<br />

“We established six criteria for healthy parenting education<br />

and our committee concluded that the GFI materials<br />

meet none of those standards” (Christianity Today, February<br />

9, 1998).<br />

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION<br />

(CDC) The CDC is an agency of the United States Department<br />

of Health and Human Services. All public health<br />

decisions are based on the highest quality scientific data,<br />

openly and objectively derived. The CDC offers numerous<br />

current publications and other resources.<br />

National Immunization Program: National Immunization<br />

Program Pregnancy Guidelines and numerous pamphlets,<br />

including Why Does my Baby Need Hepatitis B Vaccine? and<br />

Common Misconceptions about Vaccination (rebuts common<br />

anti-vaccination arguments), are available through CDC.<br />

National Immunization Hotline (USA): 800/950-0078, 8:30<br />

A.M. to 5:30 P.M. EST Monday to Friday.<br />

Group B Strep (GBS) Prevention Coordinator: The GBS<br />

order form lists eleven different brochures, flyers, policies,<br />

posters, a video, and a slide set on the prevention<br />

of perinatal Group B Streptococcal disease. The Group<br />

B Strep <strong>Association</strong> (GBSA), a community-based parents’<br />

advocacy, educational, and support group for parents who<br />

have lost infants to GBS disease, is listed as a link on the<br />

CDC website: http://www.cdc.gov/publications.htm. Contact:<br />

Publications Request (Specify department: National<br />

Immunization Program, National Center for Infectious<br />

Diseases, or GBS Prevention Coordinator), Centers for<br />

Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road, NE,<br />

Atlanta, GA 30333 USA.<br />

CHILDBIRTH FORUM FOR THE PROFESSIONAL CHILD-<br />

BIRTH EDUCATOR is brought to you by the Pampers<br />

Parenting Institute. Classroom materials include flip-chart<br />

material and tear-off pads which are sent to your home,<br />

birth center, hospital, or office free of charge. Contact:<br />

800/950-0078.<br />

CPR AND FIRST AID INSTRUCTION In the United<br />

States, the American Red Cross and American Heart <strong>Association</strong><br />

provide training in adult and infant-child CPR<br />

and certification for instructors. For information on local<br />

affiliates or chapters and instructor programs, contact<br />

the American Heart <strong>Association</strong> at 800/242-8721; website<br />

http://www.amhrt.org.<br />

For locations and instructor training for the American<br />

Red Cross, contact your local chapter. The American Red<br />

Cross may offer Healthy Pregnancy/Healthy Baby, Infant-<br />

Child CPR, First Aid, Child Care For Providers, Family Planning,<br />

AIDS, and Substance Abuse Prevention Programs.<br />

Not all services are available in all locations. Contact your<br />

state, provincial, or local chapters of the Red Cross or Red<br />

Crescent for information; website: http://www.ifrc.org/.<br />

The American Safety & Health Institute also offers<br />

courses and instructor certification. Contact: ASHI, 13202<br />

Burnes Lake Dr., Tampa, FL 33612 USA; website: http://<br />

www.ashinstitute.com.<br />

DEPRESSION AFTER DELIVERY (DAD) is a national<br />

self-help organization which provides support, education,<br />

information, and referral for women and families<br />

coping with blues, anxiety, depression, and psychosis<br />

associated with the arrival of a baby. Depression After<br />

Delivery promotes awareness of these issues to all sectors<br />

of the community and advocates for changes affecting the<br />

well-being of women and their families. PUBLICATIONS:<br />

DAD offers its members a newsletter, Heart Strings, at no<br />

charge with membership. DAD also has several information<br />

packages available, such as General Information Packet<br />

for Professionals ($15), General Information Packet for<br />

New Mothers and Fathers ($5), and Information Packet<br />

on Starting a Postpartum Depression Support Group ($5).<br />

To obtain information, locate a support group in your<br />

area, or obtain a list of medical professionals in your area<br />

who are knowledgeable about PPD, contact Depression<br />

After Delivery, PO Box 1282, Morrisville, PA 19067 USA;<br />

phone 800/944-4PPD.<br />

continued on page 15<br />

14 • IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4

RESOURCES from page 14<br />

MARCH OF DIMES BIRTH DEFECTS FOUNDATION “So<br />

that more parents may know the joy of a healthy baby”<br />

is what this organization is all about. A new video, Baby’s<br />

First Months ($19.95 plus $4.50 shipping and handling),<br />

and the pamphlet, Newborn Care, are available. Healthy<br />

pregnancy brochures and videos are available in the Public<br />

Health <strong>Education</strong> Materials Catalog. Contact hour information<br />

is offered to professionals through the Nursing Module<br />

Catalog. To order, call 800/367-6630; write March of Dimes<br />

Birth Defects Foundation, PO Box 1657, Wilkes-Barre, PA<br />

18703 USA; or e-mail at http://www.modimes.org.<br />

RISK REDUCTION SUDDEN INFANT DEATH SYN-<br />

DROME (SIDS) Although the cause or causes of sudden<br />

infant death syndrome remain unknown, the incidence of<br />

SIDS has declined from 1.3 per 1,000 in 1991 to 0.87<br />

per 1,000 in 1996 in the United States and other countries.<br />

This has been accomplished largely through public<br />

education campaigns informing parents about several<br />

important risk factors associated with an increased risk of<br />

SIDS. Available scientific research supports having healthy<br />

babies sleep in the supine position; not exposing babies<br />

to cigarette smoke, either during pregnancy or after birth;<br />

making the sleeping environment as safe as possible;<br />

and breastfeeding rather than bottlefeeding. Contact the<br />

SIDS Risk-Reduction <strong>Education</strong> Back to Sleep Campaign<br />

at 800/505-CRIB (800/505-2742). English and Spanish<br />

reminder cards, videotapes, and brochures for parents<br />

or professionals are available. Website: http://www.sids.<br />

org/news.htm. For SIDS reduction information in English,<br />

Spanish, German, French, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian,<br />

Finnish, Japanese, Norwegian, Swedish, Chinese, and<br />

Dutch, check website: http://sids-network.org/basic.htm.<br />

POSTPARTUM SUPPORT INTERNATIONAL (PSI) This<br />

membership-based international organization is dedicated<br />

to increase awareness about the emotional reactions women<br />

experience during pregnancy and throughout the first year<br />

postpartum. Professional membership is $60. PSI brings<br />

together research from diverse disciplines and international<br />

journals. The website provides a resource guide,<br />

bibliography, and support network. Search published<br />

materials on postpartum mood and anxiety disorders,<br />

post-traumatic stress syndrome, depression, or psychosis.<br />

Need advice or assistance? Want to join a postpartum<br />

support group? Listed individuals and organizations are<br />

committed to offering assistance for mothers, fathers,<br />

and families in need of social support, information,<br />

and treatment. The list includes the United States and<br />

various international locations. Website: http://www.iup.<br />

edu/an/postpartum/. Contact: Jane Honikman, MS, Postpartum<br />

Support <strong>International</strong>, 927 N. Kellogg Avenue,<br />

Santa Barbara, CA 93111 USA; phone: 805/ 967-7636;<br />

fax: 805/967-0608; e-mail: thonikman@compuserve.<br />

com.<br />

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO) More than<br />

forty publications related to maternal and child health<br />

are listed in the WHO Publications Catalog of New Books<br />

1991-1998. Look for scholarly reports of studies, training<br />

manuals on midwifery, Care in Normal Birth: A Practical<br />

Guide 1997, and policy statements on such compelling<br />

topics as the <strong>International</strong> Code for Marketing of Breast-<br />

Milk Substitutes and female genital mutilation. To quote<br />

The World Health Report 1998, Life in the 21st Century: “The<br />

world is poised to achieve unprecedented good health in<br />

the next century — if lessons from the past are understood<br />

and heeded.” Website: http://www.who.ch/. Contact: Distribution<br />

and Sales (DSA), Division of Publishing, Language,<br />

and Library Services, World Health Organization (WHO)<br />

Headquarters, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland; phone<br />

+41 22 791 2476/2477; fax +41 22 791 4857; e-mail<br />

publications@who.ch.<br />

If you are aware of a low-cost published or internet<br />

resource or organization to be considered for this column,<br />

please send the information to Rebecca Ward, ICEA Director<br />

of Resources, 5351 Strasbourg Avenue, Irvine, CA 92604<br />

USA. While the information available in this resource list is<br />

believed to be accurate and up-to-date, the <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Association</strong>, its Board of Directors,<br />

and the <strong>International</strong> Journal of <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong> staff do<br />

not make any representations or warranties with respect to<br />

content, accuracy, or use. The opinions and information<br />

are presented for educational purposes only. This listing<br />

is not presented as all-inclusive in nature.<br />

■ Rebecca Ward, BS, is ICEA Director of Resources and Resources Columnist<br />

for the <strong>International</strong> Journal of <strong>Childbirth</strong> <strong>Education</strong>. Rebecca is a Certified<br />

<strong>Childbirth</strong> and Lactation Educator teaching at Mission Regional Hospital and<br />

Irvine Medical Center in California. She and her husband Martin have raised<br />

five children in Irvine, California.<br />

<br />

IJCE Vol. 13 No. 4 • 15

STATIS-<br />

by Dale King<br />

Teenage Pregnancy<br />

A recent report from the Center for Disease Control and<br />

Prevention (1998) indicates that teenage pregnancy in<br />

the United States has decreased since the beginning of<br />

the 1990s. The 1996 birth rate among teenage mothers,<br />

the number of births per 1,000 teenage women, fell 3<br />

to 8% depending on the age specific subgroup. Among<br />

teenage women 15 to 19 years of age, the 1996 birth rate<br />

fell 4% from the previous year and 12% from 1991. The<br />

decline in the American teenage birth rate was pervasive,<br />

occurring in all of the fifty states, the Virgin Islands, and<br />

the District of Columbia. In only three states, Delaware,<br />

Rhode Island, and North Dakota, was the decline statistically<br />

insignificant. This decline follows the sharp increase<br />

in the birth rate that occurred from 1986 to 1991 when<br />

the teenage birth rate increased 24%.<br />

Between 1995 and 1996, teenage birth rates declined<br />

for all racial and ethnic groups with the exception of the<br />

Cuban teenage birth rate which increased from 29.2 to<br />

34.0 births per 1,000 Cuban teenage women. The greatest<br />

decline from 1991 occurred among non-Hispanic black,<br />

Puerto Rican, and other Hispanic teens. These groups<br />

experienced a decline in the birth rate of approximately<br />

20%.<br />

Despite recent declines in the teenage birth rate, it<br />

is still true that more than one million teenagers in the<br />